CHAPTER 1

THE BOSTON REVELATION

What better way to learn to run soft than in the world’s most famous race?

“Short strides. Rapid turnover. Landing under your center of gravity. Forget these three things, and you will be destroyed.” I was desperate, so I listened closely as my friend Robert Forster, a physical therapist who runs Phase IV, a high-performance training center in Santa Monica, explained that my only hope of finishing the Boston Marathon was to completely change my running form. Right now.

After all, it was April 5, 1999. Boston was 14 days away. I had a non-refundable frequent-flyer ticket in hand, but I had not run in four months due to a shoulder wrecked in a bike crash and intense, searing pain in my left hip whenever I jogged a step. A doctor had just told me I’d developed Paget’s Syndrome—excess calcium buildup in the joint. He said it was caused by years of running, which he recommended I never do again.

So I had no choice. “Your only hope of survival is to baby your muscles and connective tissue by minimizing impact and running softly,” explained Forster, who got his start in physical therapy by readying and rehabbing two famous athletes—world-record 100-and 200-meter runner Florence Griffith “FloJo” Joyner and her world-record-setting heptathlete sister-in-law, 3-time Olympian Jackie Joyner Kersee. “Running softly means no heel-striking,” he said, “just short, fast strides that keep your foot strike right under your body mass, your center of gravity—not out in front. The smaller steps take the workload and distribute it over more foot strikes, reducing the forces at each one. If you allow your strides to lengthen, you’ll fly through the air further and crash down harder, naturally heel-striking, and putting more leverage and stress on your muscles and tendons.

Miracle on Boylston Street? The author ran the soft-running gauntlet.

“To picture it, think of the Road Runner,” he added. “His legs go in a little circle, and barely touch the ground. They go so fast they blur. You are going to shoot for a cadence of 180 strides per minute. You’re going to spin your legs like the Road Runner.”

As Forster finished his lecture, Steve Tamaribuchi, a chiropractor visiting from Sacramento, handed me a strange pair of purple-colored plastic handgrips he had invented called the e3 Grips. They looked like what’s left over after you squeeze your hand around a lump of clay.

“You say you’ve got hip pain?” said Tamaribuchi. “Hold these as you run and it’ll straighten out your arm swing, which will reduce the excessive sway of your hips. I bet the pain will disappear.”

Right, I thought, rolling my eyes. I’m going to run with tiny little steps for 26 miles holding these funky purple handgrips.

An hour later, however, I was pinching myself. After leaving Forster’s office, I’d gone right to the gym and run 5 miles on the treadmill—with no pain. Facing a mirror, I could clearly see that my arms were swinging vertically, not crossing over my chest at an angle, just as like Tamaribuchi had said.

As a test, I’d occasionally put the grips aside. Each time I ran without them, my hip would hurt again. Then, when I regripped, the pain would instantly disappear.

I was amazed. And I knew right then that the 103rd Boston Marathon would be one of the most interesting experiences of my life.

AFRAID NOTTO RUN SOFT

During the next 10 days, I alternated short-stride, rapid-turnover running with the elliptical machine, logged 34 total miles in 5 runs, and topped out with a 14-miler before beginning my “taper” and flying east. In the past, ramping up the mileage so quickly would have left me with pulled muscles, shin splints, and tendonitis. But now, on my most accelerated schedule ever, I simply felt great. Connective tissue, muscles, and hips were all perfectly pain-free.

Still, 26.2 miles seemed nuts to my friends, who had a tradition of flying in from all over the country every year to meet in Boston to run the marathon as “bandits”—people who hadn’t met the qualifying times to officially run the race. They were amused by my little strides, weird grips, and lack of training. On an easy three-mile out-and-back to Jamaica Pond the day before the marathon, they placed bets on the mile I’d quit, break down, or permanently injure myself at. I’d been thinking of this as a neat experiment; they thought it was suicide. I started to worry.

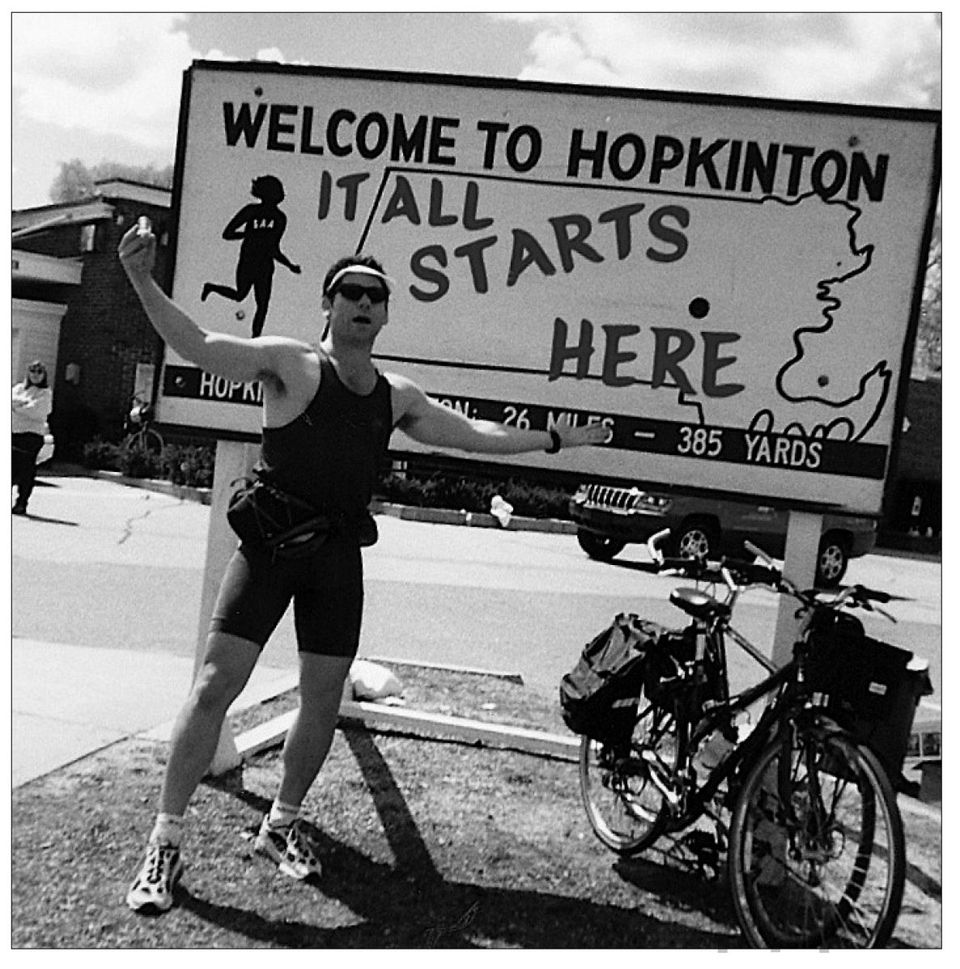

By the time we arrived in Hopkinton the next day about an hour before the 12-noon start, I was scared to the point of paranoia. Clutching my Grips as if holding invisible ski poles, I jogged around the start area mouthing my soft-running mantra over and over: “Short strides, rapid turnover, footfall under the body’s mass.” People looked at me as if I was a religious fanatic praying for a miracle.

The Experiment Begins

The miracle part was right. All the logical scenarios that played out in my head ended the same way: my muscles imploding 10 miles from the finish, leaving me a scorned, pathetic failure marooned miles from home. I wasn’t necessarily worried about being an illegal runner anymore—there were hundreds of numberless bandits openly warming up around me, including a pair of fullsuited Blues Brothers imitators, and one guy with a turn-out piece of brown shopping-bag paper pinned to his shirt with the word bandit scrawled on it—but not being an official entrant still could be a problem. I’d have no access to the pickup buses that ferry broken-down runners to the finish line in Boston, where my wife and kid would be waiting for hours.

What was I thinking?

When the starting gun sounded, I didn’t budge. I jogged in place for eight minutes as the multitudes crossed the start line, then burrowed into the middle of the last pack to find role models—preferably slow ones. Above all, I did not want to push it, and didn’t need fast people to tempt me. The plan worked. When we got moving, it was absolutely glacial. The first mile took 13 minutes—a perfect warm-up. Finishing, not speed, was the goal.

Throttling back the engine took all my focus, as the crowd’s enthusiasm, even way out in the suburbs, was unlike anything I’d ever experienced at an athletic event. As my body imperceptibly sped up to easy 10-minute miles, it didn’t seem like running as much as riding an energy current of love. From the sidelines came endless slices of oranges and bananas and shouts of “Go Bob!” An hour later I noticed that another bandit running just off my left shoulder was wearing a red T-shirt with “Bob” written on it.

Cruising with Blues Brothers bandits.

“Short strides, rapid turnover,” I repeated, fighting the urge to surge. Even the incredible sight and sound of thousands of crazed, out-of-control women at the deafening Wellesley College “Scream Tunnel” near mile 13 could not distract me. By then I was down to 8-minute miles, my normal pace, but not pushing it—although I wanted to. My body craved speed the way a starving man craves food, but I firmly kept the governor on the engine, well aware it could suddenly blow.

By mile 16, with legs feeling indestructible and body and soul nourished by the adoring crowd, the paranoia began to fade. I was—for lack of a better word—flowing. I was high beyond a runner’s high. I had achieved nirvana. I don’t think I had ever felt this good in my life. It got even better when I hit Heartbreak Hill—mile 20—at 2 hours 44 minutes. I did the math. At this rate, I’d get my PR by 10 minutes!

Exhilarated, I stopped in front of the “Heartbreak Hill” banner and pulled my disposable camera out of my race belt pocket, only to discover that there was just one shot left, which I was saving for the finish line. No problem. Three different people in the crowd offered to snap a shot of me on their own cameras and mail it to me (which, in fact, a guy named Scot Butcher did two weeks later).

I was already in love with Boston by then, and that cinched it. I posed with arms raised triumphantly, then glided up that famous 300-foot, 1-mile hill with my tiny, pinwheeling, Road Runner stride. I passed Bob. I passed dozens of red faces grimly clumping up the monster as if they were about to be eaten by it. I wasn’t running—I was levitating.

At the top of Heartbreak came an astounding revelation: Only five miles to go. No pain. Hey, I thought, I can get my PR by 15 minutes!

A mile into the long gradual downhill into Boston, I blew by Tim Carlson, a training buddy and fellow Triathlete magazine writer from L.A., so fast that his hair would have surely ruffled in my breeze if it wasn’t plastered to his skull. Surprised to see him, I slowed and began babbling about my breakthrough with the abbreviated stride and the amazing e3 Grips.

Heading up Heartbreak Hill.

Tim did not share my elation. Although he had actually qualified for Boston, now he couldn’t speak and looked wasted, as if he’d already been to hell and was dreading the return trip. He was on his way to a personal worst.

So I waved good-bye. But not before the worst possible thing happened: I got cocky.

In my mind, I’d become invincible, a man of destiny. As the descent continued, I picked up speed, lengthening my strides like a racehorse. Soon, I was no longer running, but galloping, bounding. My footfalls seemed to stretch yards ahead of my body; I was airborne, Olympian, god-like. The pace effortlessly pushed to 7:30, 7:15, 7:00 miles, maybe less. I started seeing myself as a TV movie, a Hollywood tale, Chariots of Fire meets Against All Odds. Oh, the story I’d have someday for the grandkids: The day old Gramps ran a PR at the Boston Marathon on virtually no training!

Then I hit mile 23.

Boiiiing!

My right hamstring pulled. Just slightly. I immediately shortened my stride and slowed down—but it was too late. I knew I’d screwed up. What a fool!

On mile 24, my right calf blew. Really blew. It knocked me to the ground.

I yelped like a wounded dog as I laid there and stretched for three minutes.

When I got up, I was seriously worried. The last two miles suddenly seemed like 200. Every inch of me was out of control. Painful spasms wracked both forearms from holding the Grips so long. And now every muscle in my left leg—not just the right—felt ready to pop. I felt like I was booby-trapped, a human land mine. One false step and ...

At mile 25, it exploded like a gunshot. My left interior quadriceps muscle—the vastus medialis—balled up into a fist of pain. I went down, screaming “Awwwwwww!” at the top of my lungs. Dozens of heads turned. “I’m a doctor—I’ll call for a medical unit,” said a red-haired woman who ran over from the sidelines with a cell phone. As I spread my legs wide like a Tibetan yoga master, lowered my face to the ground, and held that stretch for a good minute, moaning and crying, as I frantically tried to massage my shredded quad with shredded arm muscles that could barely control my hands, a drunken fellow ran up and launched a tirade just inches from my nose. I can still feel his spit.

“Get the hell up! Get up, dammit!” he yelled. “You ain’t here to lay around, lazy-ass! Get up and finish this thing now or I’ll kick you all the way there!”

God, I thought, I love these people. The Boston Marathon is run on Patriots’ Day, which commemorates the day two centuries ago when the American Revolution started, when the Redcoats marched on Lexington and Concord. So everyone in Boston is officially off work and on the sidelines, drinking, partying, cheering on the river of runners in the city that created the modern marathon. In no other city on Earth would they care this much.

My last mile was 20 minutes of jogging on eggshells, praying for my body not to explode. Making the left turn on to Boylston Street, with only 100 yards to go, I was overcome by a sun-breaks-through-the-clouds moment of joy. I’d broken four! The clock at the finish read 4:04, but since I started eight minutes late, my time was 3:56. Not a PR. But I broke four!

I handed my throwaway camera with the one shot left on it to a woman behind the barrier and posed, bursting with happiness. Then I tip-toed across the line, wrapped myself in a foil blanket, and wandered around in a state of total bliss. If I was to die at this moment, I thought to myself, my life will have been complete.

WHY NOT ALL THE TIME?

Like everyone, I’ve got a nice highlight reel of personal triumphs, but my finish of the 1999 Boston Marathon was off the charts. Of course, I wouldn’t recommend anyone doing something like this, but from a pure learning standpoint as an athlete and journalist, the lesson was invaluable: Soft Running and a vertical arm swing work.

If I had stuck with Forster’s plan to the very end, instead of reverting to my old long-stride pounding, I’d have pulled it off with a PR.

That’s when it hit me: Soft Running shouldn’t be used just for undertrained fools like me, but all the time. If it’s far easier on the muscles and joints in one marathon, imagine the stress it’ll save over a lifetime of running. It could extend your running career by many decades.

From that point on, I began questioning everything about running, especially the long-established maxim that training is everything, technique doesn’t matter much, and you don’t mess with someone’s natural form. Technique does matter. I proved it.

I began researching new running methods and meeting innovative coaches and athletes outside the running mainstream. I talked to successful coaches in the mainstream, too. And I was surprised to find that, when it comes down to it, the two camps actually agree: There is a better way to run—safer as well as faster. And as you get older, that way becomes even more important.

I have been a believer in Soft Running ever since Boston. It was clear to me after that crazy day that there was a lot more to running than simply putting one foot after the other.

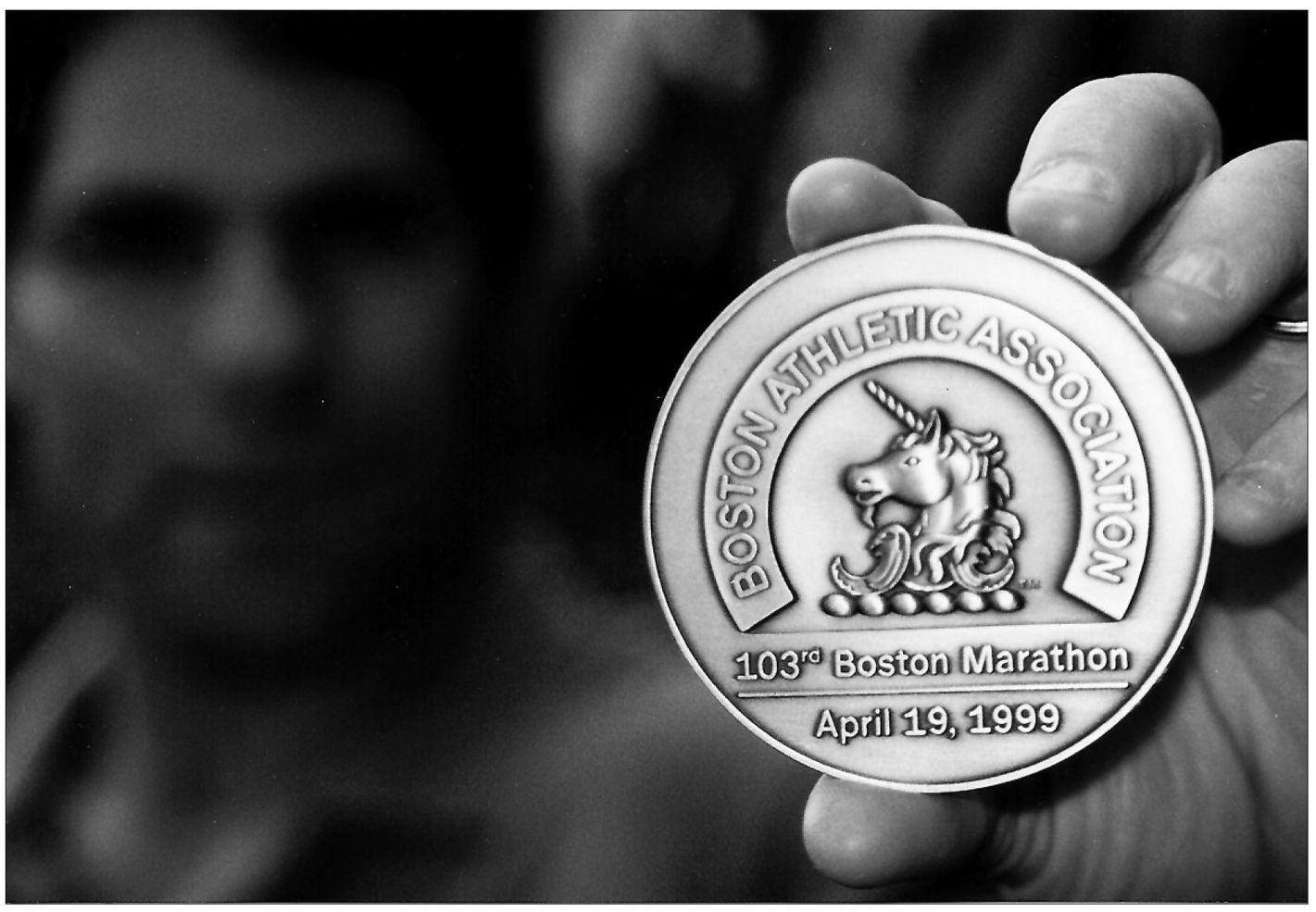

Expo paperweight—and finisher’s medal.