INTERVIEW 3

The Leader of the Pack

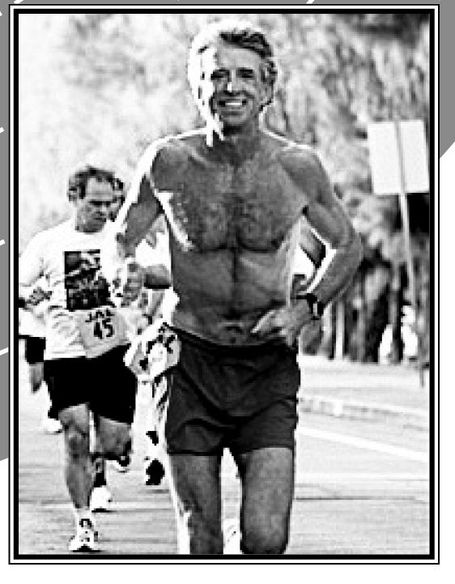

He kicked off the running boom, historians say, with his win in the marathon at the 1972 Olympics. He invented a widely emulated business model that let runners make a living when it was rigged against them. He led the fight to let runners win prize money, like other world-class athletes. He served as chairman of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency. Every step of the way, anywhere from 140,000 to 180,000 miles worth of them by various counts, it seems that Yale grad Frank Shorter put himself in a position to have maximum positive impact on the sport of running.

Running five miles a day by age 11 in his hometown of Middletown, New York, Shorter first achieved fame in his senior year of college by winning the NCAA 10000-meter title in 1969, the first of five U.S. national 10k championships through 1977. He won his first marathon, Japan’s prestigious Fukuoka, in 1971, then won three more in a row there. Clearly America’s best distance runner and the Olympic favorite at the time of his ’72 gold medal, it is widely accepted that he had a second Olympic gold medal stolen from him by a drug-taking East German in the 1976 Games. When Shorter’s competitive running career ended at the beginning of the eighties, 30 million Americans were jagging for fitness (up from 2 million decade earlier), and he turned to the multisport scene, even winning the World Masters Duathlon Championship in 1989.

A lawyer who only briefly practiced law, Shorter was 60 when he talked with me for Run for Life by phone from his home in Boulder, Colorado, on January 22, 2008. Busy, organized, and bristling with the self-confidence of someone who’s done—and is still doing—all he set out to do, he discussed his past glories and his plan for staying superfit deep into the future with long aerobic workouts, intervals, crosstraining, and lots of weight lifting.

At age 11, I wanted to be a great downhill skier, and the best downhillers were the French. I was told that they did a lot of running as part of their training, so . . .

I said, “Okay, I’ll do that.” It was two and half miles to school and two and a half back. I’d run two or three times a week, maybe more. And I actually found a pair of basketball sneakers that I modified low-cut—that time they were sort of hard to find—and I convinced the principal of the middle school to let me wear these white sneakers, because at the time you could only wear black high-top shoes. Yeah, I actually convinced him, because I was, quote, “training.” So that’s when it started. I was the only kid at school wearing sneakers. In gym class, I convinced the teacher of the gym class to allow me to run laps around the field rather than do gym class.

I was pretty serious about skiing. And then when I was in high school—Northfield Mount Hermon prep school, to fast-forward—I had to make a decision about whether or not I wanted to be a skier or a runner. And I’d been having more success running. So, I decided to keep running into college.

I was the New England champion in both cross-country in the fall and the 2-mile in the spring. This is the league that has all the northeastern prep schools, like Andover, Choate, St. Paul’s, Groton, Middlesex. That fall, I actually set a course record at every cross-country course I ran, so I guess I was doing pretty well.

I was born in Munich [on October 31, 1947] because my father was a military doctor in the occupation after World War II. He’d actually gone through medical school in three years. They were pumping the doctors through at the tail end of the war. He and my mother had grown up five houses apart on the same street in a little town in upstate New York called Middletown, about 15 miles from West Point. It was a coincidence that 24 years later I went to prep school there.

Running was one of the reasons I went to Yale. One, I wanted a very good school. I was pre-med. And also the track coach at the time, Bob “Gieg” Giegengack, had been the 1964 Olympic track coach. I got to Yale the next year, 1965. I knew I still wanted to run; it was more that I just wanted a place with the best resources for everything I was doing, whether it be athletic or academic. So from my perspective, Yale was the perfect place.

At that point, the longest race was two miles. And cross-country only ran 3½. My longest run was five miles in Van Cortlandt Park (in the Bronx) until my senior year in college, when I finished 18th in the NCAA cross-country, which was 10,000 meters, also in Van Cortlandt Park. That was sort of when things began to become apparent that I might have some ability beyond college. The top 25 were All-American. This was a big deal back then, because I obviously was the highest finisher of the Ivy League runners in the whole country.

Then it was literally three months later at the NCAA indoor meet, I actually finished second in the 2-mile national championships. So all of the sudden, I was getting really fast. Then, at the end of my senior year, another three months beyond that, I won the NCAA 6-mile and was second in the 3-mile a couple days later. I got really good—my curve sort of just took a steep rise my last year in college.

Since you couldn’t make a living running back then, you did it for the true sport of it. The expectation was that you might stick around for a year or two and maybe make an Olympic team, and after that you were supposed to go on with the rest of your life.

I actually had a medical deferment (from serving in Vietnam) that occurred because I was training so hard. There was a meet against the Russians in 1970 that I won; this was a big deal back then. It was the Cold War—and I was on the cover of Sports Illustrated. But on that same trip, I started urinating blood. So when I got back home, I went to the doctor, had X-rays and stuff, and that was the basis of a medical deferment. Because the military didn’t want to take me and take the risk of paying me disability for the rest of my life.

The effect: It allowed me to keep running. Because the goal was to try to make the Olympic team. Within a year, I won the 5- and 10000 at the 1970 U.S. championships. And the next year, in June of ’71, I won the Pan Am trials 10,000 and marathon. Later that year I won the Fukuoka marathon, which was the de facto world championships. So I improved very quickly.

I had run my first marathon in 1971, the national AAU championship, and finished second to Kenny Moore. That’s the one where I turned to him and honest-to-God said, “Kenny, why couldn’t Phidippides [the first marathoner of Greek legend] have died here?” I actually said that. I just knew I was going down. (laughs) I had just realized what “the Wall” was.

Kenny actually wrote an article for Sports Illustrated that appeared two weeks later, so that line appeared in print. Which also shows that I actually said it. He went on to a great career and wrote the screenplay for the second Prefontaine movie, the better one, Without Limits. He just wrote the book on [Oregon coach Bill] Bowerman, The Men of Oregon. He also was 4th in the ’72 Olympic marathon.

The Olympics was about seeing how far I could go. I think I was lucky in college. I’d been coached very well by Geig and taught how to coach myself. [Shorter routinely ran twice a day for a total of about 17 miles a day in the seventies.] Actually, when I got out of college, I didn’t have a coach. I was it. So I knew about incremental goalsetting, and for me it was just another step higher. If you think about the logical step, the steps were never too big. From NCAA championships, to national championships, to Pan Am trials, to Pan Am Games, to Olympic Trials, to Olympic Games. You always had the higher goal in the back of your mind, but it’s the incremental ones that are more important, because from my perspective, I didn’t know if I was going to level off. But the whole point was, the way I set the goals, that was as far as I was going to go.

GOLDEN IN MUNICH

Although I might have been the favorite, I did not assume I’d win in Munich. For the Olympics, I didn’t assume anything. All you do in a marathon, the way I’ve always run the marathon, is—at the highest level—I always said, look, ten people have the training to win. Then you get into the mental part, and three of those people are going to have a good day. There’s a 30% good-day rate, I think, in a major marathon—if they’re drug-free. And at that time, they pretty much were. So my goal was just to be one of those 3. So even just going into the Olympic Games, all I wanted to do that day was run as well as I could and try to be one of the three that had a good day.

You see, in the marathon, you don’t run against any other individual; your competition in the marathon is whoever is running next to you. (laughs) That’s your competition. And it doesn’t matter what point in the race it is. If they’re there, they’re a competitor, and they’re a threat.

[Running on the last day of the Olympics, Shorter and the lead pack passed through the 10k mark at 31:15. He pushed the pace in the next 5k to under 15 minutes, establishing a 5-second gap by nine miles. Then he relentlessly stretched the lead.]

The old coach’s advice is, “You run through the tape.” I had backed off. And I knew I was going to—and again I use the words “most likely”; I never said “I’m-gonna-win-this”—I knew I would most likely win if I kept pressing and nothing happened. See the difference? You don’t start celebrating until it’s over. Anybody who runs track and field will tell you, if you do, you’ll get nipped at the tape.” (laughs)

[Shorter entered Munich stadium 2 minutes ahead of, in order, Belgian Karel Lismont, defending Olympic champ Mamo Wolde of Ethiopia, and Kenny Moore. He won the marathon in 2:12:19, the then-second-fastest Olympic marathon time.]

On the bus back to the Olympic Village after the medal ceremony, I ran into my old coach [Geigengack] who I hadn’t seen in two years. Geig said to me, simply, “Your life will never be the same.” He was right.

But at the time, I didn’t think my life was changed. In a sense, I had kind of a negative example of what I wasn’t going to do: Mark Spitz, who basically tried to instantly capitalize on his fame [with his appearance on the Bob Hope show and numerous commercial endorsements, forfeiting his amateur status]. And that’s fine. That was good for him because that’s what he chose to do. But it was good for me that I could decide for myself, “no, that is not what I’m going to do.” My feeling when I won was to say, “okay, I’m going to let this all settle in for a while.” And to do that, I’ll just go back to my life before the Olympics, which was law school. I’d been going to law school full-time at the University of Florida the two years leading up to the Olympics. I went back, finished, graduated, came out here to Colorado and took the Bar, and then started training again for the 1976 Olympics in Montreal.

So, no, I never really thought my life would change in terms of leveraging it or capitalizing on it. Because it wasn’t—again, you didn’t earn your living doing this. My perspective was, it’s only going to be limited, it’s only going to be for a short period of time, and it’s not what I want to do anyway because I feel I could do other things. My view of capitalizing on that time was that you did it if you really didn’t have anything else and you’re really going to have to make your retirement within two or three years after the Games. Because there wasn’t going to be anything else you could do to make a living. That wasn’t my view, because I could do lots of things.

I ran the second Olympics with a broken foot. I’d broken what’s called the navicular bone inside my ankle, but I had to run on it. I couldn’t take time off to let it heal because it was late February, which meant I’d have had to take off until the first of April, and the Olympic Trials were the end of May. So I couldn’t do that, and kept running on the broken foot through the Olympics. Which is why I didn’t run the 10,000 meters in Montreal [even though he’d won the trials 10k]. I wanted to make sure my foot would last.

As for [marathon gold medalist Waldemar] Cierpinski, the entire East German team was on the drug program. You had to be [on the program] to be on the team. It wasn’t as if they had a choice. Again, my reaction to that was not to say anything at the time, and then when it came time to help form USADA, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, I saw that as a window that was not going to open in that way. I worked with President Clinton’s drug czar, Barry McCaffrey, to set up the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency. It was set up by the U.S. Olympic Committee in 1999. We took over after 2000.

My feeling on this has always been, “don’t complain, don’t sound like sour grapes, do something.” I think I’ve taken what was obviously a disappointment that shouldn’t have happened and turned it around to now know that I had a big part in what’s going on with Marion Jones and Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens and testing kids in high school and the Tour de France and everything else. I think it’s worked out well. Because rather than to try to remedy my own situation, I felt I should try to put my effort—because of the unique situation I had, with regard to the notoriety and the ability to speak and have people listen—I would do it to try to change the system so that it most likely wasn’t going to happen again.

NEW BUSINESS MODEL FOR RUNNERS

I got my law degree, but never practiced; I just went into a business. I started my own businesses so that I could put my name on them and gradually erode the rule that didn’t allow athletes to endorse products, so essentially earn a living. You see, when Mark Spitz did the commercials, he became a pro. Ironically, because of the work I did in the opening up of the sport—I’m the person who came up with the idea of the trust fund that allowed athletes starting in 1981 to win money and put money into their own individual trusts, and take it out for education, living, and medical expenses. Because we knew the Eastern Europeans—the East Germans—were doing the same thing, and the international federation passed it. Eventually, it just sort of just eroded away, and now the sport’s open—you can win money. But the irony is when Mark Spitz decided he wanted to try to swim again, he got the benefit of that, you see what I’m saying? At age 47 (when Spitz tried to make the Olympic team)—it didn’t work, but that’s okay.

The thing is, I decided to make my living not from the sport or from doing endorsements, but working what I call ancillary—close to the sport, involved in the sport, but actually actively working. In 1978 I started my store and clothing line. I came up with the trust fund idea in 1981.

I actually did the first TV commercial for Hilton Hotels in a 3-way deal with the U.S. federation. That’s what allowed athletes to do commercials. I worked out a three-way deal where the U.S. track federation got $25,000 a year in an agreement with Hilton to have a commercial made with an “amateur athlete.” Well, I volunteered to be the athlete. And then I had a side agreement with Hilton to actually work for them. For those 2 years, I helped establish running courses around some of the Hilton Hotels, and believe it or not, we worked on the first Health Mark Diet. The Hilton Hotel restaurants were the first to have healthy diets with the little logos by them.

This was in 1978—before the trust fund idea. You can see that was sort of halfway. I wasn’t in any jeopardy with this agreement because the federation agreed to it. They just agreed to supply an athlete; I volunteered to be the athlete on behalf of the federation. Me and Hilton came up with the idea, and I had Hilton approach the federation.

So I stayed in the sport. You can fast-forward to my involvement in the drug agency and see that it’s a continuation of what I’ve always done.

[In 1977, Shorter was forced to take a break from competition because of his bad ankle, which was operated on the following spring. The long rehab had a silver lining: time to practice his cycling and work on his store and clothing line.]

After that, I lasted two or three more years, taking 3rd in the 10000 in the ’79 PanAm games. And in 1981 and ’82, I won a couple of big road races in the U.S., but that was pretty much the end.

FIT FOR LIFE: WEIGHTS AND CROSS-TRAINING

At that point, it becomes a matter of staying fit. I still do interval training, the same routine, but I don’t run for all of my exercise. I still work out sometimes twice a day, but in the morning I get on an exercise bike and ride, and in the afternoon either run or do the intervals on an elliptical machine using my pulse rate. And then I also do a tremendous amount of weight training. I probably do some weight training four days a week. Some for the upper body, some for my legs.

I’ll do the hamstrings and quadriceps with the machines, and calf machines and toe raises. I do two separate workouts for the calves, quads, and hamstrings, then I do some core work, which is sort of torso training along with a lot of sit-ups. The upper body, I use dumbbells. I got away from barbells because I was getting too competitive. I got my bench press up to 190 pounds; I weighed 138 at the time, and I figured, well, maybe I’ll just back off. I do dumbbell curls, presses, and lat pull downs, dips, and chin-ups.

I think once you get past 35, you can stay as strong, or actually stronger than you were when you were younger. And if you don’t, you lose muscle mass at about three to five pounds a decade, even if you’re very active. You have to do the weight training to even maintain muscle mass. I’ve been doing this for 25 years.

And I’ve been riding the bike—now I’m 60—when I first turned 40. In fact, for two years in a row, I was the world champion in the Masters division of the duathlon, The Desert Princess series. I started cross-training 20 years ago, and it came in very handy in 1998. Because it turns out I had a broken back, and the nerves in my legs were getting impinged, the L-5 and the S-1 nerves, and so after I had the back fusion and they cleared up the problem, I was all set. I’d already done so much cross-training, it was already engrained in me. I did a lot of cross-training. I probably work out an hour and a half every day.

That’s just aerobic or anaerobic. It doesn’t include weights. The last 25 years, I probably spend as much time working out as I did when I was running 20 miles a day, it’s just that I’m not running all that time.

I enter races but don’t compete. I’ll jump in a half marathon and see how close to an hour and half I can come. I don’t run marathons anymore, but I’ve run four half marathons in the last 6 months. That’s typical. I run them slowly and have fun. Again, for me, it’s to stay fit and not look as old as I am.

All I’ve really done is substitute cross-training into the same kind of routine of easy aerobic conditioning and once or twice a week hard anaerobic training, which is a very small percentage of the overall training. It’s just that now, instead of doing it all running, I’ll mix it up.

DON’T GO HARD

If older runners are doing anything wrong, I think it’s—I call it “The Myth of Overexertion.” People think you have to go too hard to get the training effect. Actually, you have to go what I call “conversational pace.” You and I are talking. And if we were running, we would want to be running at an effort to where we could still be talking like this. And if we couldn’t, because we sort of had to pause to catch our breath, we’d actually be going too hard. You can stay fitter by going at 70% of your max effort than you can by going harder than that. You do the other training to race. But any aerobic exercise you do to be fit can be done at conversational effort.

A lot of people are going too hard. The effect is diminishing returns. You get hurt, get tired, you get in a downward spiral from workout to workout.

I wore my knees down, but anybody—if they live long enough—gets osteoarthritis. You wear out your joints. They’re wearing out, but they’re still working. Yeah, it hurts.

I actually inject with a product called hyalgan; it’s purified rooster comb. It’s absorbed by what you have left, and it stimulates synovial fluid so that you can basically have the knees of an 18-year-old for 8 to 10 months. And I’ve done this for about 5 years. I had no meniscus left in my right knee, and very little in the left. And when I use this stuff, I can run without pain for about 8 to 10 months. It’s much better than getting a new knee.

It works for me. It’s like anything. Glucosamine and chondroitin works for a certain percentage of the population. This works for a certain percentage within that percentage. You see—it’s not a guarantee, but it’s worth trying.

I don’t do any supplements. Because as former chairman of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, I have to tell every Olympic athlete—and now triathlete—in the Olympics, that they take supplements at their peril because there’s not enough oversight by the FDA to ensure that what they’re taking isn’t tainted. In other words, you have no idea with a supplement whether or not it’s working because what they say on the label is making it work or what’s not on the label that’s illegal is making it work.

VEGGIES, FISH, WHOLE GRAINS

Whether it’s the pyramid or food groups, I eat a lot of vegetables. I don’t eat any refined sugar anymore, and I found that increased my desire for fruit. Eat a lot of granola and whole grains, and lot of fish—lot of salmon. I eat meat maybe once every two weeks. Because I think there are some essential amino acids in meat that you just need. In other words, I eat meat to craving. I crave some red meat maybe once every two weeks.

I’ll have a lot of complex carbohydrates. Lot of granola, lot of wholegrain bread. The Atkins (low-carb) Diet is great if you never want to contract a muscle again. Because you need complex carbohydrates for the glycogen that’s the fuel source, and you can’t fight Mother Nature. We knew, when we did the carbohydrate depletion diet in ’76—you were supposed to just eat protein and very little carbohydrate the first part of the week, and then carbs the second part, and it would super-saturate you with glycogen—and you know what?—we found out that in the depletion phase you have no energy at all. And why many people go off the Atkins Diet is that you have no energy. Now, if you want to be in bed, totally sedentary, on an IV, eating nothing but protein, you’ll lose weight. Fine. But if you want to be an active person, you’re not going to have the energy.

Actually, hate to cut this short, but you know I’m going to have to go. Got to meet someone I’m working out with. We’re doing intervals—interval training. And I’m not going to let this person wait. Bye.