INTERVIEW 9

The Historian

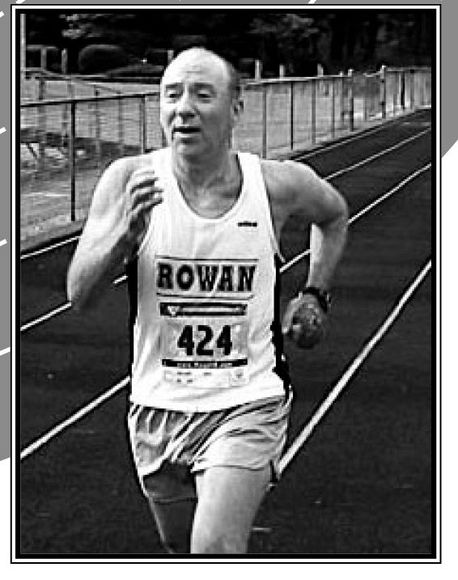

Tom Osler is a numbers guy by profession—a New Jersey university mathematics professor who has published 100 papers on the subject—but when it comes to running, he’s more like an historian. Starting off as a 14-year-old enthralled with the sport two decades before the running boom, he met and worked with the modern pioneers of running, quietly helping them to shape the sport. As he did, running helped shape his own life. He’s run over 2,000 races since he ran a 4.7-mile race in Camden, New Jersey on December 4, 1954, and has gone on to race nearly three out of every four weekends for more than 50 years—every event dutifully logged in his immense race diary. The muscular, opera-loving father of two grown sons is not only a link with the sport’s early days but also a champion with three national championships in the 1960s (25k, 30k, and 50-mile). He’s authored three important running books, been an early running organizer and founder of several running clubs, and been inducted into the Hall of Fames of the Road Runners Club of America and the National Road Running Club.

Modest and self-effacing, Osler was three months shy of age 68 when he spoke to me on January 22, 2008 about his life, his unique body-weight/racing times formula, his fitness and running regimen (which includes 5k races almost every weekend), and his love for a sport that he says literally saved his life.

I’ve run practically every day of my life since February 1954, when I was 13. Mostly because I like it. I like the way it makes me feel. The periods of time when I could run well were a bonus.

I had a wonderful boyhood growing up in Camden, New Jersey. I tried the usual popular sports like football, baseball, basketball; couldn’t do any of them well. Tired of my nerd status, I went out for the track team to gain some self-respect.

In running, usually you first try 100 yards or 200 yards—I couldn’t do those well—then keep going up until you’re at the end, which in those days was the mile. So that’s where I wound up.

On April 26, I got a stopwatch for my 14th birthday. So I started running a timed mile every day as hard as I could, hoping to someday be the first man under four minutes.

I trained harder than most people, and became a mediocre high school miler. In April of ’55 I got my first win in the mile in a dual meet between Camden and Atlantic City High Schools, in a time of 5:10.2. The best I would do was 4:54—good enough to win one out of three or four high school track meets. Couldn’t win any championships with it. There was still the occasional kid who could run 4:40 or 4:30. But it was all right. It made me the best miler on my team.

I realized at that time that I wasn’t going to be a great runner. I didn’t have the speed. If I was in a ten-mile run and there were 30 people, I’d finish about 10th or 15th. I said to myself, “Well, hell, I love doing this—it’s really fun. Okay, so what if I never become a great runner? I like it, so I’m going to keep doing it.”

Part of the fun was being involved with the local running scene and meeting people—sometimes the best runners in the country.

When I was 14, I’d read in the newspaper about the Shanahan Marathon in Philadelphia, so I went over there. There were less than 20 people in the race. I wound up running 11 miles and had to quit. Before the race, I had a chance to sit down and talk with this great runner, Ted Corbitt, who’d been a marathoner on the 1952 Olympic team. Later in life, he did ultramarathons. Naturally, I wanted to hear what Ted had to say. He told me to be careful about all this enthusiasm for running, and be sure I did well at school. He would have a powerful effect on me.

(Corbitt, who died at 88 in 2007, once held American records in the marathon and the 100-mile run and is considered America’s ultramarathoning pioneer. A black man in a era of racial discrimination, he earned a master’s degree in physical therapy at NYU in 1950, ran his first marathon in Boston in 1951, and, as the president of the New York RRC in 1959, organized the U.S.’ first ultramarathon event. Known to run 200 miles or more a week, Corbitt was one of the first to champion running for exercise, and remained a full-time physical therapist into his 80s).

You really had to know Ted to appreciate the man. He was very quiet, didn’t say a lot. And there was something about him that was just different from everyone else. When you were with him, he very much motivated you, impressed you with the fact that you could do all kinds of things that you thought were beyond you, that you thought were difficult. He had a way of making it seem easy. He’s the only person I ever met like that. He had a way of doing difficult things like going out and running for 70 miles. He lived in the Bronx, and in training for his ultras, he’d run around Manhattan Island, carrying change so that he could ride the subway back if he got in trouble. Around Manhattan is 35 miles; occasionally, he’d do it twice.

This sort of thing was mind-boggling, especially in those days.

Corbitt wasn’t very communicative verbally. He liked to write me letters. Probably most of the letters were about course measurement. I was part of a committee that he formed to propagate proper course measurement techniques.

We were friends, but because he lived in New York City, and I lived in the Philadelphia area, we never got that close. Not close like I got with Browning Ross, who lived about 15 miles from me.

Ross and I were friends. Ross was to running as George Washington was to the United States. He was on the Olympic team in ’48 and ’52 in the steeplechase. He was national champion at practically everything with regard to distance running—except the marathon. He founded the Road Runners Club of America in 1957 in Philadelphia. That’s what really got running going. Before that, there were only a handful of races to run in this area. When he started that, we suddenly had races every week.

He started this magazine, the Long Distance Log, which he typed up and mailed out himself. That started in 1956 and went all the way to 1973. Came out once a month, had about 25 pages, and every race in the country was in there. There were so few races then that you could do that. If Browning had had the business mentality, that could have become Runner’s World. He was a mentor to me, about 15 years older. It was hard to run with him; he always wanted to run fast, and it made me very uncomfortable. Every time I ran with him, I said, “I’m not going to do this again.” (laughs) Even when there came a point when I was much better runner than him as he grew older, I didn’t like to train with him. He trained too fast for my taste.

GOING SLOWER TO GET FASTER

Like I said, I was a mediocre runner, and I stayed that way for a long time after high school. My college, now Drexel University, was an engineering school with no track or cross-country team. So I never competed in collegiate events. But I did run all that time in the open races. After the Road Runners Club had formed, and I was running 5-milers, 10-milers, I ran every day and raced almost every weekend—without distinction.

That started to change when I was 22, in grad school, and read the book, Run to the Top, which described how Arthur Lydiard, a brilliant New Zealand coach [who died in 2004 at 87], trained his Olympic champions.

Lydiard had this idea that you should do long, slow runs that build your base. Now, this was an idea that was always pooh-poohed by everyone I’d talked to. We’d always done interval training. Everyone said that slow running was worthless jogging, and would get you nowhere. Slow running would make you slow. And here was this great coach saying that slow running would not make you slow; it would make you strong.

So I tried it, and found I loved it. I just loved running slow. It was very comfortable and enjoyable. And very much to my surprise, in a few years I was running much, much better.

By the time I was 24, I was no longer finishing in the middle of the pack. Now I was finishing near the front—if if not occasionally first.

I thought, “Okay, I tried the long, slow stuff. Now let’s add the second half of Lydiard’s formula: sharpening (speed work), and see what that does.” And when I tried that, I won my first national championship. (Osler won the 1965 national AAU title in the 25k in 1:27:09. In 1967, he won national championships in the 30k (in 1:40:40.8) and 50-mile (in 5:52:33) and ran his best marathon, 2:29:04, at Boston.)

In 1967, I privately published “The Conditioning of Distance Runners,” probably the best thing I ever wrote on running. It’s only 32 pages and still circulating underground. What caused me to write it was Lydiard’s book. I wasn’t Olympic champion material, so I really couldn’t do the kind of schedules he had in the book. I reduced them, modified them for a less-gifted runner, more ordinary, like myself—and it worked.

ARRESTED FOR RUNNING

The championships gave me respect, you know: “Oh yeah, he’s a good runner.” But when I was doing my best running, the public didn’t even know what a marathon was. At that time, running was nothing (compared to other sports). It did not become anything the ordinary person noticed until the very late sixties, early seventies. When I’d go out and train and run on the road, they’d usually ask, “Are you a boxer? I thought you were a fighter out doing roadwork.”

They had no idea. Nobody was out running on the road. “I’m a distance runner,” I’d say. They’d say, “What’s > that?” I’d say, “We have these 10-mile races, and I do those.” They’d say, “Geez, I never heard of that.”

People were more formal in those days. When you had a race, there was usually a clubhouse or a YMCA or something associated with it. People didn’t show up at a race in their sweat clothes; they showed up in their street clothes with a gym bag and their running stuff in it. So you expected to have a locker room, a shower, et cetera. After the race, you’d go back and take a shower. The reason you could do this is that running was so small; there were just very few people running. Even at the Boston Marathon you had these things, although logistics made it a bit different. When I first ran it in 1963 or 1964, I took the train up there. Everybody stayed at the Lenox Hotel near the finish line in those days. Buses drove you down to a high school in Hopkinton, where the race started. Boston only drew about 200 runners.

So few people were out running that you felt real weird out there. It took a long time before I felt all right putting a pair of shorts on and running down the street. Even in warm weather, you just didn’t do that—until the running boom came. “What’s wrong with that guy?” they’d say. You didn’t do that in public.

Loads of times, if I went out running at night, I’d often have a policeman come up and follow me in his car. “What the hell’s this guy doing?” he’d think.

In 1964, when I was a graduate student, I was once tackled by a policeman. Tackled me, put me in his car. He didn’t say “stop.” He just opened his door and tackled me. It was wintertime. There had just been a light snowfall. I was doing this long, 17-mile loop of mine, and at that point was running through a park. Just me on this road, nobody out, and I see this cop car coming right towards me, directly at me. I’m running on the left side of the road, and the cop’s on the left side of the road. I wave at him to give me some room, get out of the way. He doesn’t get out of the way. He comes right up, slams on his brake, and stops right in front of me. So I ran around the side of his car, and as soon as I got along the side, the door flipped open and he sprung out like a jack-in-the-box, tackled me, and pulled me into the car.

I’m in the car, utterly startled, thinking, “What the heck is going on?” He picks up the radio, and says, “I got him.”

I was really mad. I looked at him and said, “You know what you got? You got a lot of trouble, that’s what you got!”

He was kind of startled at my, uh, arrogance. I explained what I was doing. I said, “Look, drive me over to the park police station. The park police here know me. I come through here very frequently. They’ll tell you who I am.” So he believed me, and took my name, address and phone number, and he let me go. But I was just steaming mad.

When I got home, I called the police to complain. They then told me what had happened. At the time I was running, a bunch of kids had stolen a car, and had driven into the park, abandoned the car, and ran off in that very direction. Naturally, he thought I was one of those kids. Like I said, no one was running in those days.

It’s interesting. Back in those days, myself and most people who ran felt very uneasy about this. We felt guilty that we were doing this. My parents didn’t like it. They said, “You’re wasting your time. You should be studying, or developing your career. Why are you wasting all that energy running?”

Everybody told you that. I was one of those few people who did it because I liked it. I didn’t care whether or not I made the Olympic team.

I came close, actually. The only event I could have possibly made the Olympic team in was the marathon. In 1967, I finished 4th in the national AAU championship marathon. That sort of made me the dark horse for the Olympic Trials in ’68. What put a complete damper on that was, because the games were going to be in Mexico City, they were going to hold the trials in high altitude—Alamosa, Colorado, which is something like 6,000 feet. The AAU set up a three-month training camp that anyone could go to prepare for this.

I didn’t want to spend the summer in Alamosa, Colorado training—since it wasn’t likely I’d make it anyway. So I didn’t try.

In 1968, I was working full-time as a math professor at St. Joseph’s College in Philadelphia, and I’d just gotten married. My wife Kathy would have thought I’d lost my mind if I’d gone, because I wasn’t that kind of person. Like I said, I always felt guilty about running, and the idea of giving up three months of my life just to run sounded insane. That was just too much. I never felt sorry for myself that I didn’t go to that camp. I think I would have been miserable. I’d been doing 50-mile runs, but I never wanted to spend all day running. It was bad enough that I was spending a couple hours a day running. There were always other things that I wanted to do. I didn’t want to just run. And that’s what you do at one of these camps; you were just immersed in running 24 hours a day. Running’s a nice complement to the other things I do in my life. But it’s not everything.

ANTI-AGING PLAN: WEIGHTS, CROSS-TRAIN, RACE, AND CONVERSATION

At 40, I began to lift light weights. Funny story: I’m a college professor, and I noticed that my right arm began to get tired from writing on the blackboard. It was really annoying in class; I was really getting a lot of pain in my shoulder. So I went out and bought a 110-pound York dumbbell set. I started playing with them, and it worked. The pain went away.

And I had read that when a man turned 35, he loses about a half a pound of muscle a year. So I thought, “Jeez, this not good. I should work against that.” I swing 5- to 20-pound dumbbells around in the morning, and have a weight bench in the basement where I press 100 pounds, 8 reps. Just recently, I started weight training my legs. I should have done it earlier, I think. I do some mild squats with 20-pound dumbbells.

I think cross-training is terrific. In fact, for six years beginning in 1987, when I was 47, I did some 39 triathlons and biathlons. But I reluctantly retired from multisport events because I had two bad bicycle accidents, and I figured that was it—it was too dangerous. I got hurt pretty bad, broke bones both times. Now, if I get hurt running—that hasn’t happened in a while—I’ll swim.

The social component of life is a key element in happiness. That’s why I teach—I have my students, my colleagues; it gives me somebody to talk to. It’s a big, big part of why I enjoy my work. I’m 67 and have no plans to retire—working or running.

I love racing, because every time you race, it’s like a reunion. It’s very motivating too, right? Most of my daily running is by myself, although again I enjoy running with people.

My wife does not run. My boys did not run—even through the running boom was on as they were growing up. They were not interested. And I had no interest in encouraging them to do it. Oh, I asked them, but they always said “No.” I’m not the kind of dad to push them into doing things; I tended to let them do what they wanted to do. That’s how my father was. He didn’t push me into running; he didn’t push me out of it, although he running; he didn’t push me out of it, although he certainly never encouraged it.

Once a week for the last 20 years, I’ve run with Marge Morris, a librarian at Brown University. I saw her running down the street one day, and we just started running together. She’s a very good conversationalist. We had a lot in common—children and so on, the same problems raising them. Marge is now the only runner who will train with me because I use such a slow pace—usually slower than 10 minutes per mile.

Running with someone is a personal thing. Most people I don’t enjoy running with—because I don’t enjoy their conversation. If you enjoy their conversation, fine. Otherwise, I’d rather talk to myself.

RUNNING STRATEGY & FORM: WALK—AND SIT ON THE “COUCH”

Jeff Galloway has done a very good job of popularizing walking while running, but it’s nothing new. It’s a technique that has been used for going extralong distance—distances longer than you could go with straight running, like if you can run a half marathon, but aren’t in shape to do a full marathon. It’s very effective. Who knows who invented it?—it’s ancient. I used it in my 24-hour ultramarathon in 1976, when I went 114 miles, things like that. It’s not new, but it had been forgotten. That’s because ultramarathoning had kind of disappeared. There had been a lot of it in the late 1800s. They mainly walked. They didn’t call it “ultramarathoning.” They called it “pedestrianism.” It was professional. They had a lot of races, usually done indoors. They had a lot of gambling on it: 6-day pedestrian races. In fact, it preceded the famous 6-day bike races.

You can read about it in my third running book, Ultra-marathoning, the Next Challenge, which was cowritten in 1979 with Ed Dodd, who started researching the performance of old-time pedestrians with me six years before. (Osler’s second book, the Serious Runner’s Handbook, was published in 1978.) The first half of Ultramarathoning, which Ed wrote, is about these nineteenth-century 6-day races. The second half, which I wrote, is about ultramarathoning.

In my training section, I wrote about using walking, which depends on the distance and how strong you are. When I won a 100-mile race at Fort Meade in 16:11:15 in 1978, I got through it by walking every 2 miles; I ran either 7 laps and walked 1 lap or ran 7½ laps and walked a half lap. That got me through the 100 miles. Galloway is doing a very good thing by reviving it.

I do use walking on shorter distances as I get older. Even in races if I need to.

I don’t use heart-rate monitors or energy foods. I used to use iced tea in the heat or warm tea in the cold—with a lot of sugar. I would show up with these insulated Coleman jugs.

I’ve never tinkered with my form, but I always tried to use my mind to get me into a very efficient running gait. I would do this by trying to relax, and just think about if any muscles seemed a little tight or uncomfortable. I used to try to imagine, while I was running, that I was just sitting on the couch—that I didn’t feel anything. My legs just went out and did it.

That worked when I was young, and for many miles during a marathon. “I’m just sitting on the couch,” I’d say over and over. I would occasionally give a thought to whether my arm swing or stride length was excessive. I would try to imitate runners that I thought were very relaxed, smooth, and efficient. Probably the person I most visualized was Abebe Bikila, the Ethiopian gold medalist in the 1960 Olympic Games. When I saw Bikila run the marathon, it was so amazing. Here was a man running 5-minute miles in his bare feet, and he was so efficient, so smooth, it just looked like he was jogging. I always held that picture of him in my mind, that seemingly effortless stride. “Be like Bekila,” I say in my mind.

I’ve heard of Chi Running and the Pose Method, but they don’t impress me very much because I think running is a very natural motion. We were born to run—it comes naturally. You can overstride and understride. But if you just leave your body alone, concentrate on moving quickly but effortlessly, then it will just figure out the right way to do it. I’ve tried to concentrate on being completely relaxed. That seemed to be the key.

The injuries come, of course, near the end of any race. You’re going to be tired, which lays the seeds for the injury. That’s where the trouble comes from. That last steps where you’re really pushing and tired, that’s where you break down.

Unfortunately, despite all my running, I’ve had a weight problem all my life. Because of all the eating. (laughs)

When I tell people I have an eating disorder—meaning I like to eat a lot—they laugh at me, because they’ve never seen me fat. Well, I don’t get that fat, but it’s very easy for me to gain weight. Typically, my best running weight was around 143. Typically, I’d get that weight in the late summer, then pick up 20 pounds in the winter, Naturally, I’d run slower. So after going through several of these cycles, up and down, up and down, I started to wonder exactly what was going on here.

I started looking at the diaries of all my races. And that’s how I came up with my formula : that you gain 2 to 2½ seconds per mile per pound. Of course, it’s only valid for data from over 2,000 of my races. Since my training is very consistent, I could predict what would happen to me if I gained 10 pounds—or if I lost 10 pounds. It worked pretty well. (See more about Osler’s weight-to-speed formula and easy ways to drop weight in a sidebar at the end of Chapter 26.)

GROWING HIS OWN BYPASS

Can someone run to 100? Yes, but it won’t be me. The reason: Genetics.

At least 20 years ago, there was a guy named Larry from San Francisco, aged 104, who appeared on the Johnny Carson Show. He was a waiter. He didn’t seem to have a long history of running, but actually ran marathons. He looked good, talked well. My impression was that he was fortunate genetically.

My genetic history isn’t that good. If my people made it to 80, that was pretty good. My father had a stroke at 75 and he died at 80. My mother died at 70 from colon cancer. So I seriously doubt that running to 100 is in the cards for me. I don’t think I’ll live that long. I was happy to wake up today. (laughs)

But I do know that running—and running a lot—will help me live longer than my genetic programming. I’ve been a runner for 54 years, doing considerably more than half an hour a day. I still do 30 to 40 miles a week. I know it’s done me well. I’m probably alive because of it.

I have had two coronary episodes and high cholesterol all my life. When I was in my 20s, David Costill at Ball State did a study of marathon runners that I was part of. I had very, very high cholesterol. I ignored it, figuring that running would protect me from anything. Then, later in life, I found out it didn’t.

I had a stroke in early 2003 when I was 63, and fortunately I recovered completely from that. In the middle of the night, I got dizzy and collapsed, then returned to bed and awoke feeling okay. Not knowing I had a stroke, I ran a 5k race that day, in my usual time. Two days later, after another dizzy spell with vomiting, I went to the hospital and was diagnosed with a stroke, caused by a blood clot. In two months, I started working and running at a reduced level again and began racing in May.

Then two years later, I had an arrhythmia, where your heart goes into a very rapid beat, so rapid that it’s really not pumping any blood. This happened twice, right after finishing a race. I was very fortunate; the first time, I came out of it immediately when I fell over and hit my head. That brought me back. The second time, I wasn’t as lucky. They tried to revive me. Fortunately, there was an ambulance there; they quickly got an external defibrillator out and that got me going. Now I carry my own embedded defibrillator.

After the arrhythmia, I went to the hospital and got a catheterization, where they look inside the heart. And they saw that one of the main arteries, the LAD, was completely blocked. They told me that they could tell by looking at it that it had been blocked for a long time. It hadn’t happened recently. That’s because there were extensive collateral vessels.

I had essentially grown my own bypass.

They told me that something like that doesn’t happen unless you are doing something like running. My cardiologist told me that in most cases, when that artery closes, people are lying on the floor feeling like an elephant is standing on their chest. When it happened to me, I didn’t even know it happened.

I had no idea when it closed. I was going about my ordinary business. If I hadn’t been a runner, I might have died.

I don’t have high cholesterol now because I take some of these statins, Vytorin. The defibrillator is there in case of emergency. If my heart goes in to rapid beats, it sends an electric shock to it, which should bring it back to normal. It’s a computer that watches what the heart is doing. It’s not a pacemaker. It’s like a cop—waiting for trouble. It doesn’t affect the way my heart beats.

HELLO OLD AGE, GOOD-BYE HARD RUNNING

I have made one change in my running because of my heart. I’ve always enjoyed running a lot of races, and I still do 50, 60, 70 a year. But previous to the arrhythmia, I’d run hard in those races. During the last few miles of any race like that, it’s uncomfortable—you’re pushing yourself. That’s the part I don’t do anymore. I don’t allow myself to press at the end of a race. I haven’t run the marathon recently, but if I do, I’ll run 9 minutes a mile. I just run easy, I stay comfortable, I don’t breathe hard, I don’t do anything stressful.

A good side effect to not pressing it is less injuries. Over the years, I’d injured everything. Usually, it’s something like a sciatic nerve. I’ve been lucky with knees—no trouble. Sometimes foot trouble, plantar fasciitis. To heal up, I’d take it easy, go swimming, something. But I haven’t had an injury for years. In fact, I haven’t had an injury since I stopped running hard after the arrhythmia.

In that sense, maybe that arrhythmia is a silver lining to the cloud.

One thing I wanted to mention is I think that running and longevity is not all that common. If you look at some of these big races—the marathons and half marathons with 20,000 runners, and you look at the age-group listings, and interesting drop-off pattern tends to arise. If you look at the guys in the 50-55, and the 56-60, and the 61-65, very roughly speaking, the number of participants in each group drops by about a third or half each time. For example, if there are 60 in the 55-59, there’ll be 20, maybe 30 in the 60-65. And it keeps cutting. That means, since I’m now 67, my changes of running into the next age-group are 50%. That’s pretty sobering. That means you have to be careful to avoid hurting yourself.

Most of that is caused by mechanical injuries. It’s not something major—a heart problem, like I have. It’s knee problems, foot problems, hip problems. I know a lot of older runners who want to run but can’t—they’ve messed themselves up mechanically.

The trouble is: You run into trouble when you’re running fast and you’re tired—like what happens in the last stages of a race. You do damage to your mechanical parts, ligaments, what have you. If you avoid doing that, you’ll last a lot longer. Of course, that works against you in a race. But when you run hard at the end, you’ll pay the price if you keep doing it. So, if you want to keep running for years and years and years, then the best thing to do is don’t run hard when you’re tired.

Ironically, a warning about going fast appears in my own book, The Serious Runner’s Handbook, written 40 years ago when I was 27. It says that “sharpening is necessary, but puts you at risk.” The concern there was mostly trying to get to a peak, a best performance. The idea was that you couldn’t run at your best year-round. Your body couldn’t take it. If you want to do your best, you have to time it for a particular event and time—the Olympic Trials, Olympic Games. The way to do is to train at a relatively slow level prior to this. And about six weeks before this, you begin running harder. The idea: Don’t waste the peak too soon. I didn’t invent this idea. It came from Arthur Lydiard. I read his book. He was the first one I knew who espoused the idea of building the base and sharpening.

Bottom line: The math (of the age-group attrition rate) is sobering. It makes you aware if you want to keep doing this, you better take it easy. Because you can easily wear yourself out. And that means no more fun.

I love running; it’s the most fun I can think of. I’ll do whatever it takes to keep doing it.