Poor Richard

BEN FRANKLIN FOUND HIS “way to wealth” in publishing. He was so successful that he retired from printing in 1748, at the age of forty-two. One of his most lucrative ventures was his almanac, published under the pseudonym “Poor Richard.” There was a huge market for almanacs in early America. If a colonial American family owned any printed item besides the Bible, it was usually an almanac, and Poor Richard’s typically sold ten thousand copies a year.1

We often remember Poor Richard’s pithy sayings on industriousness: “Haste makes waste,” “a penny saved is twopence clear,” and “no gains without pains.” These were moralistic, practical aphorisms stripped of any specifically Christian content. But standing alongside these proverbs were other religious references that reflected Franklin’s idiosyncratic views and the buying public’s demands. On the first line of Poor Richard’s first calendar—January 1, 1733—was the solitary word “Circumcision.” This was a reference to the Church of England’s liturgical calendar, as January 1 was traditionally the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ. Jesus was understood to have been circumcised eight days after his birth on Christmas. Further down, other references to the church calendar dotted the list: “Epiphany,” “Septuagesima,” “Ash Wednesday,” and more.2

Faith ordered time in eighteenth-century America. We properly emphasize Franklin’s skepticism about faith, yet Poor Richard’s year was interwoven with the festivals and seasonal markers of Christianity. His Puritan parents would not have acknowledged the Anglican church calendar, but Franklin’s Philadelphia had a strong Anglican presence. Indeed, Franklin himself maintained a rented pew at the city’s Christ Church. Most of the people mentioned in Poor Richard’s calendars were either saints or British monarchs. The latter spoke to the colonists’ deep commitment—as of the 1730s—to the king of England. It was a distinctly Protestant calendar, too, with notes like “Luther Nat. 1483” for Martin Luther’s birthdate of November 10.3

Deism was not the whole story of Franklin’s religion. Franklin and his fellow Founders lived and breathed Christian culture, whatever their quibbles with specific Christian doctrines. Yet hints of Poor Richard’s unorthodox views did appear in the almanac’s pages. August 1733’s poem spoke of climate, noting how “the Gods assign’d” the weather patterns of the most habitable climes. A traditionalist reader of the only extant copy of this first almanac (now held at the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia) was bothered by this rendering, which hinted at Franklin’s notions about multiple created gods. The reader blotted out “the” and the plural “s,” and added a singular “hath”—“God hath assign’d,” the faithful reader corrected it. Franklin’s concept of plural gods would not have received a warm reception from many Americans, in his time or later. But he still lived in a world where a January 1 reference to circumcision needed no explanation.4

Even before becoming Poor Richard, Franklin kept laboring for financial security and independence. He had established his own press in 1728 with Hugh Meredith. But like his London pal James Ralph, Meredith turned out to be unreliable and undisciplined. Franklin’s sturdy Junto friend William Coleman warned him that people often saw Meredith staggering about “drunk in the streets, and playing low games in alehouses, much to our discredit.” Franklin arranged to buy Meredith out of the business, and in 1730, Ben became its sole proprietor.5

The next obvious move, for someone of Franklin’s age and station, was to get married. But he could not easily find a spouse. Franklin already had a child, William, whom he would bring to the marriage. The identity of the mother, and the birthdate of Franklin’s son, have always been mysteries. William was apparently born in Philadelphia in 1728 or 1729; his mother might have been a prostitute. Silence Dogood had commented on women in the colonial cities who, seeking to “revive the spirit of love in disappointed bachelors . . . expose themselves to sale to the first bidder.” In one of the most frank passages of the Autobiography, Franklin confessed that before his marriage, the “hard-to-be-governed passion of youth, had hurried me frequently into intrigues with low women that fell in my way, which were attended with some expense and great inconvenience.” He knew he should stop going to prostitutes. He worried about catching venereal disease, “a distemper which of all things I dreaded, though by great good luck I escaped it.” Paying for sex was a dangerous and undisciplined habit, just the kind of thing he had vowed to avoid.6

Still, Franklin struggled to reconcile his stated commitment to rational virtue with his habit of visiting prostitutes. Indeed, Franklin’s “low intrigues” came while he was composing some of his most important spiritual writings, such as “Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion.” Had they known, his parents and sister Jane would have suggested that he was reaping what he had sown. No faith in Christ meant no power over sin. But Franklin’s experience was hardly unusual. He was in his early twenties, with growing financial resources and no structures of church or marriage to rein him in. It might be more surprising if he had avoided illicit escapades, especially in London. Franklin’s experiences paled in light of the exploits of the Scottish biographer and former Calvinist James Boswell. Boswell’s European tour of the 1760s led him to contract multiple cases of venereal disease. He also cuckolded Jean-Jacques Rousseau, as Boswell traveled with and bedded Rousseau’s wife Thérèse. Like Franklin, Boswell tried to swear off prostitutes, even as he pestered the Continent’s greatest philosophes with inquiries about the afterlife.7

There are good reasons to think that William’s mother might not have been a prostitute, though. If she was, how would Franklin have known that he was the father? Perhaps the mother was the wife of one of Franklin’s friends or business associates. Maybe the husband had gone away on a long trip to the Caribbean, or to Britain. In any case, Franklin realized that he was the father and that he needed to take care of William. (This was unusual, as women have almost always carried the burden of raising children born out of wedlock in American history.) William added to Franklin’s struggles in finding a spouse. In the Autobiography, Franklin dubiously blamed his lack of options on his status as an artisan printer. His tactics did not make things easier. Franklin injudiciously requested that one set of prospective in-laws pay off his debts with a dowry.8

After several failed wooings, Franklin returned to his on-and-off relationship with Deborah Read, whom he had courted prior to his London sojourn. He and Deborah had discussed marriage before he left Philadelphia in 1724, but he ignored her and only sent her one letter while in England. He later called this one of the great “errata” of his life. The jilted Read went on to marry a noaccount potter named James Rogers. Franklin blamed this development on his negligence, but it is notable that Read married Rogers just nine months after Franklin left Philadelphia. Perhaps she forgot about Franklin as quickly as he forgot her.9

Regardless, Read was never happy with Rogers. She “soon parted from him,” Franklin recalled. Refusing “to cohabit with him, or bear his name,” rumors circulated that Rogers had taken another wife. “He was a worthless fellow,” Franklin concluded. Debts prompted Rogers to run away from Philadelphia and go to the West Indies, where he died. Franklin regarded Read with pity, as she was “generally dejected, seldom cheerful, and avoided company. I considered my giddiness and inconstancy when in London as in a great degree the cause of her unhappiness,” he wrote.10

Their “mutual affection” revived upon Franklin’s return, but there were a host of complications facing them if they got legally married. Should Rogers reappear (it was not certain he was dead), Deborah could be charged with bigamy. Creditors could force Franklin to take responsibility for Rogers’s debts. The couple avoided these potential difficulties by entering a common-law marriage in September 1730. In effect, they announced their intent to cohabit together without going through the legal process of matrimony. Common law marriages were not unusual in colonial America. Franklin figured that this all worked out for the best: “None of the inconveniencies happened that we had apprehended, she proved a good and faithful helpmate, assisted me much by attending the shop, we throve together, and have ever mutually endeavored to make each other happy.” Referencing God’s purpose for creating Eve in Genesis 2, Franklin could not ask for more than finding a good “helpmate” as a wife. Thus he “corrected that great erratum” as well as he could.11

Although bits of evidence would suggest that Deborah harbored resentment toward Ben’s child, William, the new couple’s early relationship was supportive and functional. Many marriages in eighteenth-century America were more like business partnerships than companionate romances. Assisted by household slaves and servants, “Debby” ran the general store on the ground floor of Franklin’s print shop, freeing him to oversee the press.12

A month after marrying, Franklin published a piece entitled “Rules and Maxims for Promoting Matrimonial Happiness.” The principles he enshrined there amounted to instructions to Deborah. Franklin combined an exalted view of marriage with a Puritan view of human depravity. Marriage was the “most lasting foundation of comfort and love; the source of all that endearing tenderness,” and “the cause of all good order in the world.” But because of the “perverseness of human nature,” marriage could become racked by the “most exquisite wretchedness and misery.” He addressed his maxims to women instead of men, not because women were the chief culprits in marital strife, but because they were more likely than men to adjust their behavior. “Good wives usually make good husbands,” he posited.13

Most of Franklin’s strictures related to women accepting their husbands, warts and all. Wives should be patient and long-suffering. Avoid “all thoughts of managing your husband,” he insisted. He told women to “be not over sanguine before marriage, nor promise yourself felicity without alloy, for that’s impossible to be attained in this present state of things.” While engaged, remind yourself that you are preparing to marry “a man, and not an angel.” React to all disappointments with cheerfulness and resilience, he advised. Do not dispute with him, lest you “risk a quarrel or create a heart-burning, which it’s impossible to know the end of.” Remind yourself often of your matrimonial vows, and do not forget your sacred promise (from the Book of Common Prayer’s marriage liturgy) to “obey” your husband. Always wear your wedding ring, a glance at which would help ward off any “improper thoughts” that might assault the mind. We do not know what Deborah thought about these recommendations.14

As Franklin’s printing business expanded, religion was one of his steadily selling topics, as it was for most colonial printers. He marketed titles on a range of religious subjects. Besides the Freemasons’ bylaws, Franklin printed the work of authors including one who sought to prove “that the Jewish or seventh-day sabbath is abrogated and repealed.” Less polemical was the seventh edition of English hymn-writer Isaac Watts’s influential The Psalms of David, Imitated in the Language of the New Testament, and Apply’d to the Christian State and Worship. Watts’s hymns would be crucial for the new congregational music of the Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s.15

Franklin’s ongoing personal writings about religion often tackled controversial issues. But his sarcastic or indirect prose frequently obscured Franklin’s own conclusions. One of his favorite targets was religious or mystical superstition. Sometimes he mocked superstition by comically threatening to employ its tactics. He once did that in the voice of “The Busy-Body,” a self-appointed moral censor for Pennsylvania society. The Busy-Body would act as a “terror to evil-doers,” he thundered. But as a gesture of goodwill, the Busy-Body in 1729 announced an “Act of General Oblivion” for all crimes and sins committed by Pennsylvania residents. This absolution lasted from the founding of the colony to the date of the first Busy-Body essay. To show that he had the wherewithal to enact serious moral reformation, the Busy-Body printed a letter from a fictional assistant who had the gift of “second sight.” This person claimed to be descended from John Bunyan, the author of Pilgrim’s Progress. Just as a number of people in Europe and America were rumored to possess powers of special knowledge and witchcraft, this clairvoyant said that he had “not only a faculty of discovering the actions of persons that are absent or asleep; but even of the Devil himself in many of his secret workings, in the various shapes, habits and names of men and women.”16

Readers at the time would have realized that this second-sighted Bunyan descendant was based on Duncan Campbell, a sensational mute clairvoyant in London in the 1710s. Although Campbell had convinced many of his special powers, Joseph Addison’s The Spectator, Franklin’s favorite publication, called Campbell a fraud. The Tatler, a brief-lived English journal founded by Addison’s colleague Richard Steele, likewise scoffed at how credulous people came to Campbell, “full of expectations, and pay his own rate for the interpretations they put upon his shrugs and nods.”17

Franklin also spoofed the case of the “Tedworth drummer,” the best known supernatural mystery in seventeenth-century England. (Arthur Conan Doyle wrote two centuries afterward that the case was still “probably too well known to require elucidation.”) In a 1661 encounter, a man named John Mompesson had exposed a fraudster, William Drury, who was playing a drum in town, ostensibly to raise funds to help the poor. Drury was arrested, and Mompesson took the drum to his home in Tedworth. The house was immediately struck by a poltergeist: inexplicable drumming and banging, furniture flying around rooms, and children assaulted in their beds. The poltergeist threw a Bible into the fireplace on Christmas Day. American colonists knew the case well. Increase Mather had written about it in his Illustrious Providences, which catalogued various episodes of witchcraft, demon possession, and poltergeists.18

The 1730 “Letter of the Drum,” a sarcastic anonymous account in the Pennsylvania Gazette attributed to Franklin, told a similar (presumably fictional) story. Franklin claimed that religious belief of any kind was at stake in the plausibility of the phantom drummer accounts. Supernatural truth was under attack by “Spinosists, Hobbists, and most impious freethinkers, who despise revelation,” referencing Benedict de Spinoza and Thomas Hobbes, the most radical skeptics of the era. Indeed, with his notorious materialism and anti-providential views, Spinoza was the “supreme philosophical bogeyman of early Enlightenment Europe,” according to one historian of the era. Such skeptics denied the “existence of the Devil” and biblical stories such as Saul and the witch of Endor (from I Samuel 28), Franklin warned. Worse, his letter lamented, the new skeptics denied accounts such as the “well-attested one of the Drummer of Tedworth.” As popular as the drummer tale was, any devout reader would know that one should not put more weight on that story’s authority than on scripture’s.19

Franklin’s fictional letter-writer said he had once started to doubt the existence of witches, spirits, and apparitions. For some years he even stopped living in fear of “Demons and Hobgoblins.” That all changed because of this story: a pastor and some of his clerical colleagues had gathered at an inn to discuss how to prevent the “growth of atheism.” That night, sounds of drums under their bed awoke the pastor and his companion, though the other two pastors said they heard nothing. The next night, the same thing happened, and one of the pastors was almost pulled out of bed by his big toe. In the midst of the racket, they recognized the voice of one of their “brethren.” He had come into the room intending to scare them, he said. But now he heard the mysterious noise, too! The prankster was frightened out of his wits. (Franklin did not address an obvious question: was the companion in the tale not just extending the trick he had started playing the night before by feigning fear?) The letter-writer admitted that some still might deny that the devil had pulled the prank, but he was convinced.20

The “Letter of the Drum” satirized people’s gullibility about the supernatural. But it also raised questions about biblical authority. If we regard stories like the Tedworth drummer as silly folktales, where did that leave comparable accounts in the Bible? Scotland’s great skeptic (and future correspondent with Franklin) David Hume argued against “miracles,” which depended solely on the testimony of witnesses. For example, if someone proposes that a dead man was raised to life, Hume suggested that we ask ourselves if it is “more probable, that this person should either deceive or be deceived, or that the fact, which he relates, should really have happened.” We should always go with the more likely explanation. Hume believed that the witnesses to the resurrection were deceived.21

David Hume, lithograph by Antoine Maurin, Paris, 1820 (detail). Courtesy New York Public Library.

This was a dangerous line of thought. Franklin, more affable and less dogmatic than Hume, always liked to work out his opinions in conversation. So he discussed his skeptical satire on the drummer’s tale by writing an opposing letter to the editor, meaning himself. (It is difficult to follow the logic because Franklin is the author of both letters, one a satire, and the other a criticism of satire. Neither is written in Franklin’s own voice. What position, we wonder, does Franklin actually take?) Writing in the voice of a concerned Christian reader, “Philoclerus,” Franklin warned against satirizing religious authority. The “Letter of the Drum” would not do “good to any one creature living.” Again we see the primacy of “doing good” in Franklin’s thought. It might be fun to mock those who believed in poltergeists, or even in the Bible’s miracle stories, but what good did it do? No one should ridicule “things serious and sacred.” Even though the “Letter of the Drum” had feigned concern about Spinoza, Hobbes, and the freethinkers, the point of the piece was actually to denigrate pastors and the scriptures, Philoclerus insisted. This was unworthy of an honest man, “even though he was of no religion at all.” Whether or not a person adhered to its doctrines, attacking institutional Christianity could do considerable harm.22

What kind of harm? Philoclerus said he would not bother to address the similarity of the Tedworth drummer to the Bible’s witch of Endor. Arguments about revelation, he assumed, would not convince the skeptical editor Franklin. (Even after he repudiated radical deism, revelation per se carried no weight for Franklin.) Appealing instead to the social utility of faith, Philoclerus reminded Franklin that “wise governments have always thought religion necessary for the good of mankind; and, that wise governments have always thought religion necessary for the well-ordering and well-being of society.” Thus, they have afforded clergy and the Bible great public respect.23

In a breathtaking passage, Franklin’s letter-writer proposed that even “if there were no truth in religion, or the salvation of men’s souls not worth regarding,” ministers and biblical revelation still deserved special honor. They are the indispensable guides to virtue and morality, “without which no society could long subsist.” People of good sense should do nothing to unnecessarily bring the clergy “into contempt.” In defending this functionalist view of religion, Franklin made an implicit argument for agnosticism. In the voice of Philoclerus, Franklin projected a basic lack of certainty about eternal verities. We do not know whether religion is true, or whether the soul has an immortal destiny. But we should act as if these things are true, because collectively we cannot bear to live as if they are not true.24

In the end, Franklin’s personae stepped back from the agnostic edge. Making an argument for the reality of unseen spiritual forces, Philoclerus contended (against Hume) that we should believe testimonies about supernatural episodes when the character of witnesses warrants it. Thus, we can trust accounts of the supernatural, like those fictionalized in the “Letter of the Drum,” when they come from “men of probity, learning and sound good sense.” The pastors in the “Letter of the Drum” concurred about the details of the story of the drums under the bed, and they had nothing to gain by fabricating it. In Franklin’s winding conversation with himself regarding the phantom drummer, the reliability of the scriptures and the testimony of the apostles were at stake. Franklin was asking whether we can really believe accounts of supernatural phenomena if the witnesses are trustworthy. Franklin was not sure of the answer, but he liked raising the question.25

Poltergeists and other eerie phenomena suffused Franklin’s world. Rumors of witchcraft did too, but that topic was a bit sensitive for a Massachusetts boy. The Salem witchcraft trials and executions had racked Massachusetts fourteen years before Franklin’s birth. His aunt and uncle, Bathsheba and Joseph Pope, were among the accusers in Salem Village. After 1692, no colonial Americans would be executed for witchcraft again, although many people in Britain and America still believed in the existence of witches. In 1730, the same year as the “Letter of the Drum,” a Richmond County, Virginia, court convicted a woman for practicing magical arts. The charges against her included “enchantment, charm, witchcraft or conjuration, to tell where treasure is, or where goods left may be found.” Because these offenses fell under a “lesser” species of witchcraft according to English law, the convicted woman received a “reduced” sentence of thirty-nine lashes.26

Franklin also tackled the subject of witchcraft in 1730, with the newspaper account of “A Witch Trial at Mount Holly.” Most historians have assumed that Franklin fabricated this trial, but he could have based it on a real witchcraft episode in rural New Jersey. Witchcraft accusations, if not convictions, remained common in the first half of the eighteenth century. It is hard to imagine why Franklin would have chosen that moment to invent the account, with no obvious provocation. A simpler explanation would be that the trial—or something like it—did happen. Another account of the Mount Holly trial exists, from the pen of an indentured servant named William Moraley. The two accounts differ in details, but they match up enough to demonstrate that they are describing the same event. That also suggests that the trial was real, although Franklin may have fabricated some elements for greater effect.27

In any event, Franklin found the folk practices for discovering witches contemptible. The setting of his story, Mount Holly, New Jersey, was about forty miles from Philadelphia, in the countryside, where doubts regarding folklore had hardly penetrated. As Franklin told it, three hundred people gathered in early October 1730 to watch officials test two defendants accused of witchcraft. The accusers insisted that the witches had made their “neighbors’ sheep dance in an uncommon manner.” They had also caused pigs to speak and sing psalms.28

In order to prove the accused (a man and a woman) were really witches, the Mount Holly accusers proposed two tests. The first was that if “weighed in scales against a Bible, the Bible would prove too heavy for them.” The second was that if they were bound and thrown into a river, they would float. The accused agreed to the tests, but only if two of their accusers (also a man and a woman) were tried by the same means. Officials brought out a “great huge Bible” and placed a large set of scales atop a gallows built for the occasion. Then “a grave tall man carrying the Holy Writ before the supposed wizard” stepped forward. “The wizard was first put in the scale, and over him was read a chapter out of the Books of Moses, and then the Bible was put in the other scale, (which being kept down before) was immediately let go; but to the great surprise of the spectators, flesh and bones came down plump, and outweighed that great good Book by abundance.” Then they weighed the accusers, and “their lumps of mortality severally were too heavy for Moses and all the Prophets and Apostles.”29

Not satisfied by this seeming exoneration, the “mob” called for the trial by water. This also turned into a farce when both accused and accusers floated. An angry sailor then jumped on the back of the accused man, trying to drown him—disrupting the point of the test. The accusing woman, dismayed that she was floating, claimed that the witches had “bewitched her to make her so light.” She proposed that she should be dunked as many times as needed to drive the Devil out of her body. The “more thinking part of the spectators” decided that anyone would float unless they choked and their lungs filled with water. Others said, in a bawdy conclusion to the account, that the women’s shifts were keeping them afloat, and that they should resume the test on the next warm weather day, when the women could be tried “naked.”30

Franklin’s satirical targets in “A Witch Trial at Mount Holly” were, again, popular superstition and belief itself. Franklin knew that the Bible was littered with stories about talking animals and demon-possessed pigs. It occasionally discussed witchcraft, too. If it was absurd to believe in popular tales of superstition today, what about believing similar stories in the Bible? Franklin had something like this question in mind when he related how their “lumps of mortality” outweighed all the Law and the Prophets. He was not making up the fanciful-sounding Bible weight test either: accusers occasionally employed that trial against witches using huge church Bibles. Evidence of Bible weight tests for witches appeared in England and Ireland, if not in New Jersey.31

Franklin’s skeptical and anticlerical views enraged Philadelphia’s traditional believers. He crossed another line with a note he included when publishing a handbill advertising a ship preparing to sail for Barbados. It was a mundane topic but an important one for Franklin’s thriving business. “Job printing” of items such as handbills was a core business for any colonial publisher. Thinking a humorous jab would make this particular advertisement “more generally read,” either Franklin or the ship captain added a warning that “No Sea Hens nor Black Gowns will be admitted on any Terms” on the boat. Sea hens were cantankerous birds, but the term was also sometimes used for prostitutes. “Black gowns” meant ministers, especially Anglican clerics, but it was also the common Native American name for Jesuit missionaries. The term was not endearing. Paired with the reference to sea hens, the note was quite rude, and Franklin caught an earful from local pastors.32

The firestorm prompted Franklin to write his 1731 “Apology for Printers,” one of the most important defenses of a free press in American history. The “Apology” was a justification of a printer’s vocation, rather than an admission of fault. Profitable printing always entailed controversy, he wrote. Of all jobs, publishing came with the most risk of offending people, because the business had “chiefly to do with men’s opinions.” (Franklin did not distinguish between opinions and comments that were simply rude.) A typical merchant might trade with “Jews, Turks, Hereticks, and Infidels of all sorts,” Franklin noted wistfully, “without giving offense to the most orthodox.” No one could reasonably expect that they would always like everything printed.33

If the publishing business thrived on controversy, Franklin blamed the audience, not printers. If he and his brother publishers “sometimes print vicious or silly things not worth reading, it may not be because they approve such things themselves, but because the people are so viciously and corruptly educated that good things are not encouraged.” Copies of popular chapbooks like Robin Hood’s Songs flew off the shelves, he claimed, while his edition of Isaac Watts’s hymns languished. (He spoke from experience regarding Watts, but no prerevolutionary American edition of Robin Hood’s Songs has survived, if one ever existed.) Still, Franklin argued that printers did prevent the publication of many bad pieces, stifling “them in the birth.” Franklin positioned himself as a moral gatekeeper who refused to print items promoting vice.34

Franklin contended that if he only catered to the “corrupt taste of the majority,” he could make far more money. But he would not print pieces that he knew would injure people. He had been offered large sums of money to do so yet had maintained his principles. Indeed, he was a long-suffering victim because of his journalistic integrity: it had made enemies out of many disaffected customers. “The constant fatigue of denying is almost unsupportable,” he moaned. But did the “publick” care about his fastidious management of the press and newspaper? No. They only saw occasional indiscretions that got through Franklin’s moral filter, and censured him “with the utmost severity” for each slip-up.35

Following this overture, Franklin addressed the matter of the “sea hens” and “black gowns.” Those words had precipitated more “clamor” against him than anything else he had ever printed, he claimed. Some said that Franklin knew just what he was doing by inserting the crass insult against ministers, and that it sprung from Franklin’s “abundant malice against religion and the clergy.” These critics had canceled their subscriptions to the Pennsylvania Gazette. Of more concern to the up-and-coming Franklin, they swore not to do any more business with him. “All this is very hard!” he exclaimed.36

Admitting that he should not have printed the advertisement, Franklin insisted that he did not intend to offend. He had business dealings and friendships with many clergymen in Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. He would have to be “stupid” to go out of his way to insult them. Anticlericalism was a tempting and fruitful topic, he acknowledged, but he said that he had never indulged anticlerical vitriol. In the thousands of advertisements and handbills he had produced before, this was the first mention of “sea hens or black gowns.” Given his record, he thought he could expect more grace from the pastors. You cannot please everyone, especially as a printer. Trying to do so could drive you to despair, but he vowed to keep publishing. “I shall not burn my press or melt my letters,” he concluded.37

In spite of the controversy, his print enterprise was getting on “swimmingly.” In addition to books, the newspaper, and numerous print jobs, Franklin became the official printer for Pennsylvania in 1730. Meanwhile, his old boss Samuel Keimer had to sell his printing business to pay off debts. Franklin, still in his mid-twenties, cultivated the image of a thrifty, respected businessman. Image meant a lot. “In order to secure my credit and character as a tradesman,” he recalled, “I took care not only to be in reality industrious and frugal, but to avoid all appearances of the contrary. I dressed plainly; I was seen at no places of idle diversion; I never went out a-fishing or shooting; a book, indeed, sometimes debauched me from my work; but that was seldom, snug, and gave no scandal.” If he had an enduring vice, it was reading. That was not so bad, as vices went. Moreover, “to show that I was not above my business, I sometimes brought home the paper I purchased at the stores, through the streets on a wheelbarrow.” He displayed the best character traits of both gentlemen and commoners. Franklin was an independent man of means, yet not too proud to push a wheelbarrow.38

Franklin’s cultivated image of independence, however, did depend on some ugly realities of unfreedom for others. In his business, Franklin often dealt with servants and slaves who were much less likely to achieve personal independence. He advertised these people in his newspaper, he purchased them and used their labor, and he may have sold them himself. For example, in 1731, the Pennsylvania Gazette advertised “A Likely Negro Wench, about fifteen years old, has had the smallpox, been in the country above a year, and talks English.” Those interested in buying her could “enquire of the printer hereof.” In 1738, he advertised an indentured servant, a “LIKELY young woman, well clothed, can sew and do household work.” She could be purchased for eight pounds, the price of her passage to America. The buyer could negotiate the length of her service. The same ad listed a “Breeding Negro Woman about 20 years of age, can do any household work.” Again, anyone interested could “enquire of the printer hereof.” He published many ads for slaves and servants, as well as notices about runaways. Franklin seems to have had less than ideal relationships with some of his own slaves. In a 1750 letter to his mother, he vowed to sell a slave couple he owned, for he and Deborah did “not like Negro servants.”39

The consummate entrepreneur, Franklin constantly probed for business opportunities. Most of them revolved around the print market. He returned often to religious texts as some of his bestsellers, whether he printed them himself or imported them for sale at his store. Seizing on the flood of German immigration into the Middle Colonies, he produced the first German-language hymn book printed in America. His customers were part of the Ephrata Community, west of Philadelphia. This monastic “Camp of the Solitaries,” as they called themselves, sought to give up earthly attachments in order to achieve mystical union with Christ. Franklin began learning German in order to work with immigrants at Ephrata and elsewhere. In 1732, he started publishing the colonies’ first German-language newspaper, the Philadelphische Zeitung. Not everything he touched turned to gold, of course. The German newspaper never caught on and soon folded.40

A 1744 retail catalogue of hundreds of books Franklin had for sale (“for ready money only”) illustrated that while Franklin experimented in skeptical thought, his book business depended on traditional Protestant texts. Heading the sale list was a “Fine large Folio BIBLE, complete, Oxford 1727.” Another Bible came with maps and notes, and he also sold various biblical Greek texts. Some titles were historic standards from the Calvinist tradition, including a French-language edition of Calvin’s Institutes. Puritan author Daniel Rogers’s Lectures on Naaman the Syrian appeared in the catalogue; it weighed in at almost nine hundred pages in some editions. Franklin also had recent titles by the English Calvinist Baptist John Gill. Some items were key texts in the new evangelical movement, to which Franklin was one of the prime suppliers of books. These included Henry Scougal’s The Life of God in the Soul of Man (1677), a book that evangelist George Whitefield credited with convincing him of the need to be born again. Other Franklin standards included the Book of Common Prayer and the works of John Bunyan, Franklin’s childhood favorite. The sale list contained rationalist and skeptical sources such as Shaftesbury, Hobbes, Locke, and The Spectator, too. But those Enlightenment texts were few compared to the number of Bibles, devotional guides, Calvinist treatises, and Greek and Roman classics Franklin retailed.41

For a voracious reader like Franklin, buying books imported from London was expensive. The kinds that sold well in Philadelphia, and the kinds that he wished to read, did not always overlap. So he and his Junto friends opened a lending library. Since they often discussed particular books, they figured that “it might be convenient to us to have them all together. . . . It was liked and agreed to, and we filled one end of the room with such books as we could best spare.” Unfortunately, this trial run at a library did not work well. “The number [of books] was not so great as we expected; and though they had been of great use, yet some inconveniencies occurring for want of due care of them, the collection after about a year was separated, and each took his books home again.”42

Franklin remained convinced, though, that mutual intellectual improvement would necessitate a viable Philadelphia library. Requiring a subscription fee was essential to its success. So he drew up a proposal by which people could get an initial library membership for forty shillings, followed by an annual fee of ten shillings. Fifty subscribers signed up in 1731. “This was the mother of all the North American subscription libraries,” Franklin wrote. Although colleges like Harvard and Yale, as well as many pastors, had substantial private libraries, the Library Company was the first in America to operate on a public subscription model. Franklin regarded it as a significant boost to his autodidactic education. It “afforded me the means of improvement by constant study, for which I set apart an hour or two each day; and thus repaired in some degree the loss of the learned education my father once intended for me. Reading was the only amusement I allowed,” since he avoided “taverns, games, or frolics.” The organizers soon sent off a book list, and forty-five pounds in cash, to London in order to obtain their first shipment of titles.43

By the time that Franklin printed the library’s catalogue in 1741, it contained 375 books. In comparison to his retail catalogue of 1744, the Library Company’s collection was weighted toward newer volumes on science, law, and history, and less toward theology and the classics. The balance reflected the subscribers’ interests and Franklin’s sense of what books were expensive and harder to get in Philadelphia. But there was plenty of religious-themed material in the library’s holdings, some of it gifts from members. Robert Grace, the Junto’s host and probably its youngest member, donated a copy of the Bible (with the Apocrypha, a standard inclusion in the King James Version) and of the great anti-Catholic compendium Fox’s Acts and Monuments of the Church. The library also held copies of an English Bible commissioned during the time of Henry VIII, a Latin translation of the Bible, and Richard Blackmore’s 1721 English version of the Psalms.44

Contemporary religious treatises also peppered the collection. Members could peruse John Locke’s works, including his writings on religion. Franklin commented on Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding in the catalogue, saying that it was “esteemed the best book of logic in the world.” The library possessed William Wollaston’s The Religion of Nature Delineated, the book that had prompted Franklin’s 1725 Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity. Boston pastor Cotton Mather was part of the collection with his Christian Philosopher. The “physico-theologians” were well represented, including The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation by John Ray, one of the books Franklin recommended for devotional reading in his personal prayer guide. There were texts on comparative religion, such as Henri de Boulainvillier’s The Life of Mahomet, which cast Islam’s prophet as a seventh-century anticlerical reformer reacting to corrupt Christian churches of the Arabian Peninsula. The library contained a few straightforward devotional texts, such as William Law’s A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life, a standard among evangelical Christians. The collection reflected a cross-section of religious titles from the period, in accord with the members’ “different sects, parties, and ways of thinking,” which Franklin noted in his description of the Library Company.45

Business and civic affairs dominate Franklin’s own accounts of his life, but matters related to his young family remained on his mind in these years. His exodus to Philadelphia meant that he was remote from the day-to-day lives of his Boston parents and siblings. A letter to his sister Sarah (Franklin) Davenport in 1730 lamented that he had heard from none of his family, save his parents, for two years. Franklin expressed relief that Sarah’s family had weathered an outbreak of smallpox, the great scourge of colonial American society. Then, a year and a half later, Franklin found himself writing to his sister Jane, who had informed Franklin of Sarah’s recent death. He lamented her loss not only as a sister but as a “good woman.” He believed that Sarah was in heaven. Her family and friends ought “to be comforted that they have enjoyed her so long and that she has passed through the world happily . . . and that she is now secure in rest, in the place provided for the virtuous.” Jane would have expected to hear this kind of hope for the afterlife, and there is no reason to think that Ben was being insincere. What could it hurt to hope for future rewards, anyway? Jane might have quibbled with his concept of heaven as the home of the virtuous, though. In the Puritan tradition, the question was not how good you were but whether God had forgiven your sins through Christ.46

The rituals of life and death pervaded Franklin’s world. Even the affluent could do little to control their timing. In late 1732, Deborah gave birth to a son, Francis Folger Franklin. Franklin’s son William seems never to have received the ritual of baptism as a child, likely because doing so would have made the question of his mother’s identity more conspicuous. Franklin may not have been keen on baptism anyway. Deborah, however, was a practicing Anglican, a fact that muted some of Franklin’s skepticism. She had baby Francis baptized at Christ Church, eleven months after his birth, though Ben was away in New England at the time. Presumably Deborah notified him that she was going to have Francis baptized in his absence. A decade later, the Franklins would similarly have their baby Sarah baptized at Christ Church a month after her birth. A humorous piece of evidence suggests that Deborah attended the church regularly in the intervening years. In 1737, someone took her prayer book from the family’s rented pew. The book was good quality, “bound in red, gilt, and letter’d DF on each corner.” Franklin scolded the thief in the newspaper: “The person who took it, is desired to open it and read the Eighth Commandment [“thou shalt not steal”], and afterwards return it into the same pew again; upon which no further notice will be taken.” In 1741, he repeatedly noted in the Gazette that someone had borrowed, but not returned, books by popular devotional writer William Law. The owner (Deborah) now had the “leisure to read them” and wanted them back.47

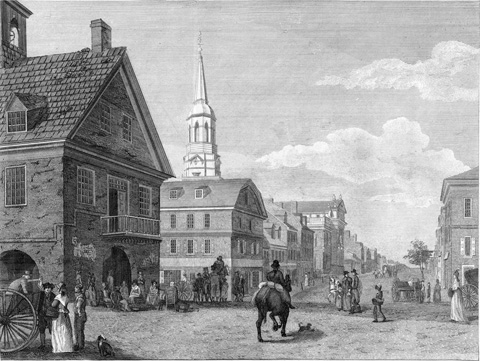

William Russell Birch, Second Street North from Market St. with Christ Church—Philadelphia, Philadelphia, 1800 (detail). Engraving. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Deborah undoubtedly took solace in her decision to have had “Franky” baptized, and thus (to Anglicans) put on the path of grace, for the boy passed away in November 1736. He died of smallpox, which Franklin emphasized that the boy had contracted “in the common way.” Some whispered that Franky had died from a botched smallpox inoculation, but Franklin insisted that this was not the case. Although he had planned on inoculating the sickly child as soon as his health was up to it, Franklin never got the chance. Recalling his brother’s battles with Cotton Mather over inoculation in the early 1720s, Franklin urged parents to give their children this preventative treatment. It carried less risk than going without, as Franklin bitterly learned. The Franklins commissioned a posthumous portrait of Franky, an unusual choice. Few people, especially in tradesmen’s families, sat for paintings in early America, and it was rare to have an individual child painted, much less after the child’s death. In the portrait Franky’s face looks incongruously old; in fact, he looks a lot like Ben.48

Through the joy and suffering of family life, work was a constant for Franklin. As Max Weber observed, Franklin never abandoned the Puritans’ commitment to industry. Father Josiah had constantly reminded him of Proverbs 22:29: “Seest thou a man diligent in his business? He shall stand before kings; he shall not stand before [lowly] men.” So Ben labored feverishly, looking for new business opportunities. Just before the end of 1732, shortly after Franky’s birth, the Pennsylvania Gazette announced the publication of “POOR RICHARD: AN ALMANACK.” The almanac contained “the Lunations, Eclipses, Planets’ Motions and Aspects, Weather, Sun and Moon’s rising and setting, Highwater, &c. besides many pleasant and witty Verses, Jests and Sayings.” Cotton Mather, in his own 1683 almanac, reckoned that these popular imprints came “into almost as many hands” as the Bible. In spite of their popularity at the time, much of the almanacs’ content seems obscure today. Almanac makers mixed traditional Protestant beliefs, British politics, astrology, and eighteenth-century astronomy. Poor Richard delivered what readers expected to find in almanacs. But his fine-tuned sense of humor helped Poor Richard dominate the almanac market in the Middle Colonies.49

Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard, 1743. An Almanack, Philadelphia, 1743. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Poor Richard illustrated, as much as any of Franklin’s publications, the way that religious beliefs saturated the printer’s world. As we have seen, faith gave order to Poor Richard’s calendar, which was the core of any almanac. The title page of Poor Richard throughout the late 1740s featured five different calculations regarding the number of years elapsed since the creation of the world, from 7,241 (“By the Account of the Eastern Greeks”) to 5,494 years (“By the Jewish Rabbies”). While we might look for skeptical implications in this indeterminate range of dates since creation, we should remember that these numbers were not original to Franklin. As with much of the almanacs’ contents, he borrowed the creation dates from other sources. Titan Leeds, Franklin’s primary competitor, placed several of the same calculations on his title page for 1733. Fifty years earlier, Cotton Mather’s almanac had given only one option for the years since creation (5,632), a reckoning that Franklin categorized as the “Roman Chronology.” To the conventional range of options, Franklin added the “computation” of English almanac maker William Winstanley (5,742 years since creation). It was not just sacred history dates he took from Winstanley and other almanac makers. He also derived the name “Poor Richard” from a combination of Winstanley’s character “Poor Robin” and the actual English almanac maker Richard Saunder (spelled without a final “s,” unlike in Franklin’s pen name).50

“Poor Richard” Saunders’s introductory essay followed the title page of the first edition. Richard said that he could try to convince the public that all he intended the almanac to do was serve the public good. But really, he just needed the cash. “The plain truth of the matter is, I am excessive poor, and my wife, good woman, is, I tell her, excessive proud; she cannot bear, she says, to sit spinning . . . while I do nothing but gaze at the stars; and has threatened more than once to burn all my books and rattling-traps (as she calls my instruments) if I do not make some profitable use of them for the good of my family. . . . I have thus begun to comply with my dame’s desire.” The real Franklin was not “excessive poor,” but perhaps this story reflected some tension in Ben’s and Deborah’s relationship.51

Blaming your wife for virtually anything was a standard comic move. What came next was the real explosion, one that Franklin needed to properly launch the first issue. He explained that he had been reluctant to cut into Titan Leeds’s almanac business, but that obstacle was soon to be removed. Why? Because Leeds’s time was up. “That ingenious man must soon be taken from us. He dies, by my calculation made at his request, on Oct. 17. 1733. 3 hr. 29 m. P.M.” Poor Richard claimed to base the prognostication on an upcoming conjunction of Mercury and the sun. Franklin had gotten the idea for using mock-astrology to predict someone’s death from a 1708 satire by Jonathan Swift, the Anglo-Irish minister and author of Gulliver’s Travels. Leeds angrily replied to Franklin in his 1734 almanac: I am still alive! he thundered. Poor Richard had “usurped the knowledge of the Almighty . . . and manifested himself a fool and a liar.” Leeds signed his retort at four minutes past his supposed appointment with death.52

Leeds’s response was fatal (pun intended), because it took Poor Richard seriously. This was just what Franklin wanted. He had already drafted a response to Leeds, which he dashed into print. It was one of the great satirical performances of Franklin’s career. Poor Richard opened with an innocent-sounding update on his progress since publishing the first almanac, ignoring the feud with Leeds. Because his audience had bought many copies of the almanac, Poor Richard wrote, his grumbling wife had been able to purchase some new clothes and “a pot of her own.” This had pacified her. “I have slept more, and more quietly within this last year, than in the foregoing years put together.”53

After this throat-clearing, Franklin sprung his trap. Reviewing the prognostications about Leeds’s death, Poor Richard noted that “at which of these times he died, or whether he be really yet dead, I cannot at this present writing positively assure my readers.” He wished he could have attended Leeds’s passing, but family business had detained him. Thus Poor Richard could not “be with him in his last moments, to receive his last embrace, to close his eyes, and do the duty of a friend in performing the last offices to the departed.” Expanding on previous musings about Providence, Franklin noted that the movement of the heavenly bodies only predicted the natural course of events. Astrology could not anticipate special interventions of God’s hand, such as an episode in which God preserved the life of someone whom the stars had marked for death. The best evidence that Leeds was dead, Poor Richard concluded, came from “Leeds’s” supposed 1734 almanac, “in which I am treated in a very gross and unhandsome manner; in which I am called a false predicter, an ignorant, a conceited scribbler, a fool, and a liar.” This could not have been the voice of Titan Leeds! “Mr. Leeds was too well bred to use any man so indecently and so scurrilously, and moreover his esteem and affection for me was extraordinary: So that it is to be feared that pamphlet may be only a contrivance of somebody or other, who hopes perhaps to sell two or three year’s almanacs still, by the sole force and virtue of Mr. Leeds’s name.” An impostor was using Leeds’s almanac to carry on a feud with Poor Richard.54

Franklin kept having fun—and selling almanacs—at Leeds’s expense, even after Leeds actually died in 1738. In the 1740 edition, Poor Richard reasserted that Leeds had indeed died in 1733. The Bradford family, Leeds’s printers, kept publishing the almanac and pretending that he had not died until they could no longer hide the truth. “These are poor shifts and thin disguises,” Poor Richard admonished, “of which indeed I should have taken little or no notice, if you had not at the same time accused me as a false predictor; an aspersion that the more affects me, as my whole livelihood depends on a contrary character.” To prove his case, Poor Richard said that the ghost of Leeds had visited him and left him a letter explaining everything. The letter confirmed that he “did actually die at that time, precisely at the hour you mentioned, with a variation only of 5 min. 53 sec. which must be allowed to be no great matter in such cases.”55

Franklin could not resist a dash of mock ghost-lore in this parody. How could Leeds’s ghost leave him a handwritten note? “You must know that no separate spirits are under any confinement till after the final settlement of all accounts,” the ghost informed him. “In the mean time we wander where we please, visit our old friends, observe their actions, enter sometimes into their imaginations, and give them hints waking or sleeping that may be of advantage to them.” Coming upon Poor Richard as he drowsed, the ghost said that he “entered [Richard’s] left nostril, ascended into your brain, found out where the ends of those nerves were fastened that move your right hand and fingers, by the help of which I am now writing unknown to you; but when you open your eyes, you will see that the hand written is mine, though wrote with yours.” Striking the same theme as the “Letter of the Drum,” Poor Richard confessed that “the people of this infidel age, perhaps, will hardly believe this story.” Few besides Franklin could so deftly weave together skepticism and satire, all while producing a bestselling series of almanacs. Poor Richard became an outsized Franklin persona well before Franklin’s transatlantic celebrity began to ascend. Soon Franklin would meet a real-life persona, George Whitefield, whose fame and friendship took Franklin’s business to a new level.56