George Campbell’s appearance was rather less formal than on his enlistment, although possibly a little more formal than during his training. For the Confederate Indians, it was a “come-as-you-are” war. The Confederacy promised their Indian allies weapons, equipment, and money. Some money came in the first year, but the promised weapons and supplies only trickled in. They were sent, but most disappeared en route, absorbed to serve the equally urgent needs of white regiments from Texas and Arkansas.

During the first year of the war George provided his own clothing. He packed up his most rugged jacket and trousers, store-bought items, because George came from a family of property. They were the same clothes that he would use for outdoor work, whether it was the spring branding at an uncle’s ranch or supervising repairs to his father’s warehouse. He wore a homespun shirt – cloth-making was a cottage industry among the Cherokee, just as it was with the other Civilized Tribes – and he kept a couple of spare shirts and drawers in his pack, along with an extra pair of trousers.

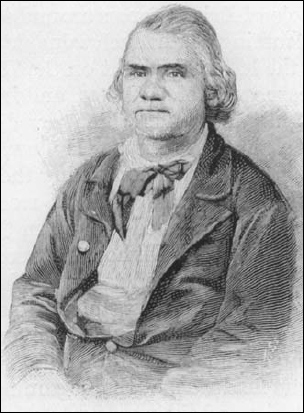

Cherokee Stand Watie proved to be one of the outstanding amateur soldiers of the Civil War. Starting with no military experience, he became the only Indian to receive a general’s commission during the war. (Author’s collection)

He also wore a cravat tied around his neck. This was a tie intended for show, not a bandana. A man had to keep up appearances when he went to war. He also wore his best riding boots – calf-high leather boots that had been made for him when he turned 18, and carefully cleaned and polished since then.

He topped the outfit with a beaver hat. Not the fancy beaver he wore when he went courting, but a sturdy, wide-brimmed hat that would repel water when it rained and keep the summer sun off his face and neck. Other men in his regiment favored a straw hat. It was cooler in the summer, but George thought that a straw hat was not quite the thing to wear on a glorious cavalry charge. He stuck a feather in it – not the hawk or eagle feather the full-bloods used, but a fancy peacock feather to show that while he might be a private, he was still a cavalier.

On the advice of a friend, he had brought along a gourd canteen and a small backpack to store his clothes and possessions. His father made him take a blanket roll to sleep in, and an oilcloth raincoat. His mother gave him a wooden plate (less likely to break than her china or earthenware), a spoon, a comb, and a small Bible. He was under instructions to read it every day. At first it sat in the bottom of his pack until the day before a battle, when it would come out briefly before returning until the eve of the next fight. By the third year of the war, George fell into the habit of reading it regularly.

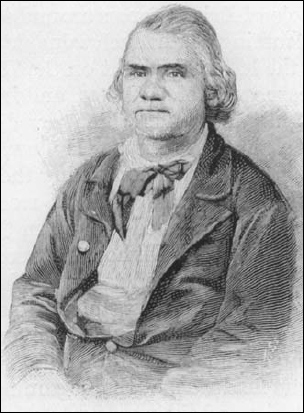

E.C. Boudinot was a cousin of Stand Watie. He served as an officer in Watie’s regiment, and was later the Cherokee delegate to the Confederate Congress. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

George wore war paint in his first few battles. His grandfather showed him the patterns that a Cherokee warrior would wear, but it struck George as something that belonged to an earlier age, like going to war wearing knee-britches and a tricorn hat. Others in his company used it in the battles against the renegade Creeks and Cherokees that sided with the Northern abolitionists, so George went along with the tradition. He also wore paint at the big battle at Pea Ridge because he wanted the Yankees to know that they were facing Indian warriors. A few of the other men carried things too far – scalping some of the Yankees they killed at that fight. Afterwards George decided that paint was too much trouble, and regarded it as rather old-fashioned.

By the time he was reading his Bible regularly, his store-boughts had worn out. In fact most of his outfit was ready for the rag-box. By then most of the stores in the Cherokee Nation had been burned down, and the stores in the Choctaw Nation or northern Texas were bare. At first he had made do with spare clothing salvaged when his family fled the Cherokee Nation for the Red River. When those ran out, he was reduced to salvaging what he could find on the battlefield or from successful raids. His trousers had come from a Kansas cavalryman that George had captured, and his shirts from a Union supply wagon that his company had taken.

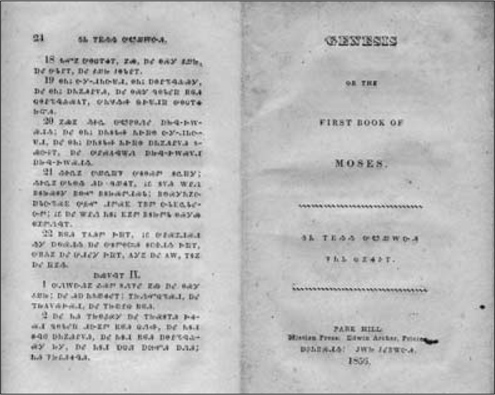

George Campbell’s historical counterparts likely carried a Bible similar to this one, which was written in Cherokee, and published in Park Hill, Cherokee Nation, in 1858. (Cherokee Heritage Center)

He had gone through two pairs of footwear. When his riding boots gave out he found a dead artilleryman with the same size feet. Then he helped capture a Union officer’s baggage and the man’s calf-high riding boots ended up as George’s share of the loot. In the summer of 1863 he decided that comfort was more important than looks and replaced his beaver with a hat of woven palmetto.

George renewed the rest of his kit in a similar manner, except for his coat. After his fiancée had sewn corporal’s stripes on the jacket, it became a talisman. He kept it until the war ended, patching it, and replacing the buttons with acorns and wood chips. By war’s end, the coat had first-sergeant’s stripes on it.

George was as well dressed as his officers at the war’s outset, and probably a little better dressed than them when it ended. They, too, went to war in their civilian clothing, and remained so dressed for the rest of the war.

Between August 1861, when George enlisted, and June 1864, when Stand Watie sent George’s regiment home, George received no clothing or equipment from the Confederacy. A few of his comrades received an item or two if they were stationed close to the Texas or Arkansas border, for example, but the majority, like George, received nothing. The Indian Nations occasionally issued clothing, but typically it was of the meanest quality. George Grayson, who served in a Creek regiment, related that his government-issued hats of undressed wool that were crudely assembled, smelled like a sheep pen, and soon lost their shape. The brim would flop down, and the hat popped into a cone shape at the least provocation. Other issue clothing was probably of comparable quality.

Watcher McDonald had an easier time getting his uniform and equipment than George Campbell. The Union Army issued some of his clothing, as well as personal equipment. Watcher had joined the retreating Creek Indians before the battle of Chusto-talasah (Bird Creek), and did not have a family to look after. He arrived at Fort Scott, Kansas, with his rifle, the clothes on his back, and a few other possessions that he had managed to stow in a bag. He still had his horse, which made him a rich man by the standards of most refugees.

The United States Army had been using Indian Scouts for many years. Although the Indian Home Guard regiments were intended as regular units, the army initially outfitted them in the same way as Indian Scouts. Watcher received a black Hardee hat and a navy-blue four-button sack coat. The coat was trimmed in infantry blue, even though the unit intended to fight a mounted war. The coat was too large for Watcher, but since the clothing issued to the Indians only seemed to come in the sizes of too large or too small, Watcher decided that there were more advantages to extra space than there were to an undersized jacket.

The hat came without a branch insignia, or regiment number and company letter. As with many other Indians in the Home Guard, Watcher stuck a pair of hawk’s feathers into the hatband – to declare his identity as an Indian, and to proclaim his warrior status.

In the first months after the Indian Home Guard was raised, only Indian officers, who like the white officers had to buy their outfits, wore any other piece of a Union uniform other than the Hardee hat and sack coat. Those were the only two pieces of uniform that the army issued the Union Indians. The only exceptions were Indians who “found” additional pieces in an unguarded quartermaster store. Watcher took advantage of those occasions to add a knapsack in which he could store his possessions, a new canteen to replace the worn-out wooden canteen he had brought with him, and some horse blankets. Those that did not go on his horse he used to keep himself warm at night.

Being issued only a hat and coat was not a hardship to the occasional Kiowa who enlisted. They did not mind fighting barelegged, and in a coat with no shirt underneath. Initially, it did not cause Watcher or the Delawares who enlisted trouble – they simply used the civilian trousers and shirts that they had owned prior to enlisting. Even those Delawares who had fled the Wichita Agency could rely on relatives in the Delaware Reservation in Kansas to supply them with clothes. But many of the Creeks, Seminoles, and Cherokees who fled to Kansas were wearing rags when they arrived. They had no source of additional clothing, no cloth to make clothing, no thread to weave cloth, and no money to purchase cloth, thread, or clothing.

Initially, the Union Army met the needs of these Indians in a time-honored manner: looting the enemy. When Confederate military stores were captured, the Indians were allowed to keep everything except military supplies. The Confederacy had its own difficulties clothing its soldiers in the Trans-Mississippi region. Virtually every stock of clothing found in captured Confederate quartermaster stores or supply wagons in western Arkansas and Missouri consisted of civilian clothing collected for use by their troops there. Just as the Confederate Indians clothed themselves with captured Union uniforms late in the war, in 1862 the Union Indians wore captured Confederate clothing. Unfortunately, these opportunities were few.

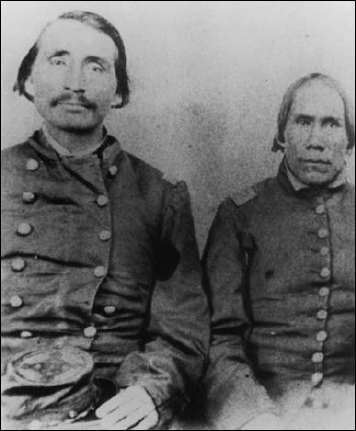

Officers of the Union Indian Brigade: Lt. Col. Lewis Downing (left) and Capt. James Vann, of the 3rd Regt. Indian Home Guard, both Cherokees. Like white officers, they purchased their own uniforms. (US Army Military History Institute)

Watcher took advantage of one windfall after the battle of Locust Grove. A Union column that included the Indian Brigade captured a 60-wagon Confederate train filled with powder and supplies near Locust Grove. The powder and military stores went to the army, but the captured clothes were civilian clothing. Watcher was able to get some new trousers and a pair of spare shirts. Later in the war, in 1863 and after the period when the Union held Fort Gibson, Watcher was able to get clothing issued by the army. This proved critical because the local weaving industry that existed in the Cherokee Nation (and all the Civilized Nations) before the war was completely disrupted by raids and counter-raids. As his civilian clothes wore out Watcher received military issue – everything from trousers and a greatcoat, to underwear like socks and drawers.

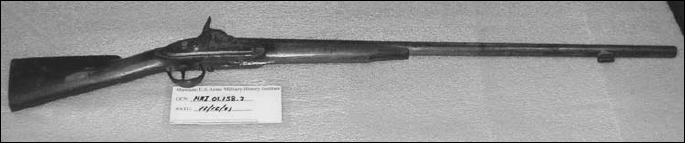

This shotgun was converted from an army flintlock musket. Fitted with a percussion lock and a cut-down stock, it was typical of the type of weapon used by Confederate forces. (United States Military Heritage Institute)

Footgear, and other leather equipment was a similar problem for Watcher. At first he wore moccasins that he had made. When they wore out, he either made new ones in his spare time, or depended upon army-issue boots or brogans. The army-issue footwear never fitted as well or felt as comfortable as his own moccasins, but there were times when that was all he had.

As the war dragged on Watcher and his companions became scruffier in their appearance. Fort Gibson remained in a state of semi-siege from late 1863 until the spring of 1865. Food and ammunition had a higher priority than clothing, and clothing for the Indian units had the lowest priority of all.