George Campbell’s equipment was as informal as his uniform. He brought his own weapons, horse, and tack. George was lucky enough to come from a well-to-do family. His father owned several rifles, shotguns, and pistols. George, as the oldest son, was sent off in fine style, with one of the hunting rifles – a surplus army flintlock that had been converted to use percussion caps – an old single-shot pistol, and a side-knife. The muzzle-loading long-arm had started out as a smoothbore but had been rifled at the same time that the flintlock had been replaced. The pistol, too, was a muzzle-loader, but his father had not wanted to part with the revolver. A blacksmith in the town near where the family lived had made the side-knife from a file, adding a wooden handle and a D-shaped guard.

A museum recreation of the Bisco and Short workroom, where Texas rifles were manufactured. The tool chest and workbenches came from the Tyler Armory, and show the piecework nature of the work done there. (Smith County Historical Society)

George’s weapons were similar to those of his companions. Perhaps two thirds of the Confederate Indian soldiers brought their own arms into the service. While the Confederate government promised their Indian allies weapons, only a few ever arrived. In August 1863, of the 2,800 long-arms in one Indian Brigade, nearly 70% were personal weapons that soldiers had brought with them when they enlisted. Over half of these were shotguns, and 21% were old smoothbore muskets. About 800 had been supplied by the Confederacy and over half of these weapons (450) were “Texas” rifles, hand-made at an armory in Tyler, Texas. Hunting rifles came in sizes as varied as the soldiers. George Grayson, a soldier in one of the Creek regiments, stated in his memoirs that one of the soldiers in his company went into battle with a squirrel rifle.

The shotgun proved the weapon of choice for Confederate Indians. A shotgun was rugged and reliable. When the barrel was sawed down it could be wielded with one hand, making it an ideal cavalry weapon. Loaded with heavy buckshot it made a formidable weapon in a charge. George kept his rifle only through his first campaign – the winter campaign against Opothleyohola’s Union loyalists. George found it difficult to handle a rifled-musket on horseback, in broken or woody terrain.

A Yankee revolver that George “found” during the battle of Pea Ridge replaced George’s single-shot pistol. While a long-arm was considered essential, many Confederate Indians carried revolvers and pistols as well. As with the long-arms, most were the personal possessions of the individual soldier, brought from home. They were varied enough to equip a firearms museum, and ranged from ancient dueling pistols to modern Colt revolvers. George Grayson reported that one of his comrades had an old horse pistol – probably an old Dragoon Colt, dating back to the Mexican–American War. As with uniforms and other supplies the Confederate Indians often upgraded their armament with pistols scavenged from the Yankees on the battlefield.

The Confederate government did send the Indians lead, gunpowder, cartridges, and percussion caps. Gunpowder was generally available in sufficient quantities, especially early in the war. Percussion caps and cartridge paper were always in short supply, however. As early as April 1862 Stand Watie’s regiment was so short of percussion caps that he sent an express rider to Fort Smith to collect some.

These shortages were not due to Confederate discrimination against their Indian allies. Rather, they reflected shortages experienced throughout the Confederacy, compounded by the distance of the Indian Territory from sources of supply. When the Civil War started there were no railroads in northern Texas, Louisiana, or western Arkansas. Supplies came by riverboat or wagon train. River travel was reliable only as far as the periphery of the Indian Territory – Fort Smith on the eastern border of the territory and the Red River on its southern boundary. From there, supplies were moved by pack or wagon train.

No Confederate Indian, and few that fought for the Union, would have been without a side-knife. This example was presented to Stand Watie, and used by him during the Civil War. (Cherokee Heritage Center)

The problem was compounded because the states surrounding the Indian Territory also needed to equip and supply their own units. The Confederacy had promised their Indian allies weapons from the Little Rock Arsenal. Instead the promised weapons – smoothbore muskets that dated to the War of 1812 – were distributed to Arkansas regiments by the state’s legislature.

One thing that Confederate Indians had in sufficient numbers were the large side-knives they carried. As much a tool as a weapon, side-knives – often called Bowies or “Arkansas toothpicks” – were made locally and intended for use around the farm or ranch. As these weapons were virtually short swords – the blades could be up to a foot long – they were effective weapons for mounted raiders.

The Confederate Indians also brought their own horses with them to their unit. Many of the Indians in the Indian Territory were stockmen, especially those of the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes. In 1861 and 1862 every enlistee either had a horse or could borrow one from friends or family.

As the war went on the Indians’ herds disappeared, occasionally seized by Indians fighting for the other side. More often, whites from both Texas and Kansas confiscating “enemy property” appropriated them. Frequently the property had brands indicating that they belonged to Indians allied with the men that had seized them. Unless the owner was on hand to protest the seizure the horses would be adjudicated as enemy property. Confederate Indians resolved their shortage of mounts by using horses captured from the Union as remounts. Even when the Indians got paid, they were paid in money, not much-needed food or goods. While the Confederacy was more scrupulous about paying for goods requisitioned from Indians, it paid in Confederate banknotes – not specie.

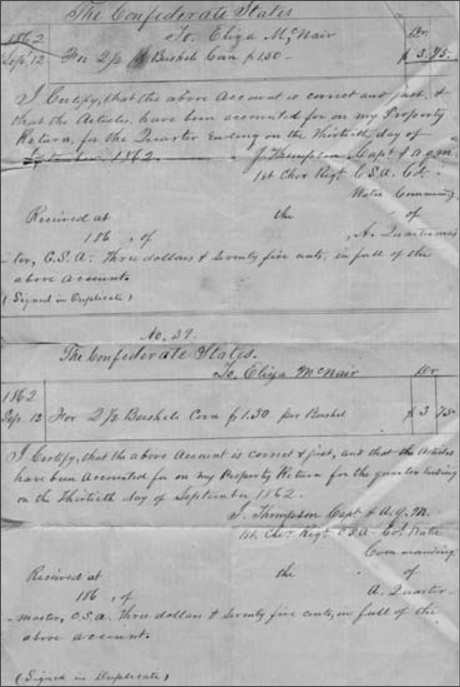

The Confederacy was scrupulous about paying their Indian allies fair value for supplies purchased, as evidenced by this receipt for fodder. Payment was made with Confederate banknotes, worthless after the war, rather than specie. (Cherokee Heritage Center)

Watcher McDonald was somewhat better equipped by the Union Army, which issued long-arms to their Indian soldiers. According to Wiley Britton, who served with the Indian Home Guard Regiments, the weapons varied by regiment. The 1st Indian Home Guard regiment was equipped with the US Army 1817 rifled musket. These had originally been flintlock weapons, but had been converted to use percussion caps. These weapons were so old that they used a spherical bullet. Indians issued these rifles were also issued spherical bullet molds. Too long to be aimed accurately from horseback, these rifles were deadly at long ranges when used dismounted. As Britton stated, “the Indians generally preferred them to the army musket then in use, and when fighting in timber where they could get a rest for their rifles, they were not to be despised on account of being antiquated.”

Soldiers in Watcher’s 2nd Indian Home Guard received Prussian rifles and muskets. These were muzzle-loading muskets built for the Prussian Army in the 1830s and 1840s, which fired the conical minié ball standard to the Union Army. Prussia, converting its army to breech-loading needle-guns in the early 1860s, sold tens of thousands of their surplus muzzle-loaders to both the Union and the Confederacy.

These weapons ranged from fair to awful. Some of those issued to the 2nd Indian Home Guard had been built as rifles, and were reasonable weapons. Others were smoothbore guns that had been converted to rifles by cutting grooves inside the barrel. They were acceptable, although less accurate than the purpose-built rifles. Others were unconverted smoothbores – short-range weapons in a campaign where long-range aimed fire was important. All had been converted from flintlock weapons to guns that used percussion caps.

The 3rd Indian Home Guard Regiment was issued a mix of Mississippi rifles and Prussian rifles. The Mississippi rifle was an excellent weapon that had been developed for use by the United States Army in 1841. While they had been superceded by the 1859 Harper’s Ferry rifle, they were better than many of the weapons used by the Union’s white regiments. They, too, used a minié ball. They were probably issued to the Indians because nothing worse remained in the armories when the 3rd Home Guard Regiment was raised in July 1862.

Along with the rifle, the Union Indians were given a cartridge box, in which to store their ammunition, which was plentiful. Yankee generosity ended with the rifle, cartridge box, and ammunition, however. No other equipment was issued to the Indian Brigade until later in the war.

The Union Army organized the Indian Home Guard regiments as infantry units, and the soldiers were paid at the lower rates of the infantryman. The Union recognized the value of mounted Indian soldiers, and the men that enlisted were permitted to bring their own horses and encouraged to ride them. This gave Union forces in the Indian Territory the effective equivalent of three additional cavalry regiments for the price of infantry units.

Initially, virtually all Union Indians were mounted. Like Watcher, they brought their own horses or borrowed mounts from friends or relatives who had spares. In 1861 the Northern Indians owned extensive herds of horses and cattle. They brought some with them to Kansas. Following the First Indian Expedition, they were able to recover some of the herds they had been forced to abandon in their flight.

As the war dragged on, their mounts became casualties and remounts became hard to find. White drovers were stealing Indians’ herds, selling the horses to the Union Army to mount white cavalry units. An increasing number of Home Guard Indians – especially those from the Indian Territory – had to fight on foot. By 1864 virtually all members of the Home Guard units were dismounted. Since ultimate victory was apparent, the Union felt no urgent need to remount the Indian regiments, despite pleas from its commander, William Phillips. The war would be won elsewhere. Except for the Indians that lived there (who could not vote, and therefore did not much matter), no one else cared about what happened in the Indian Territory.