When in garrison and not on campaign both George and Watcher lived in one of the Indian Territory’s numerous “forts.” The forts of the Indian Territory were more logistics centers than fortifications. The United States Army had erected most for the purpose of housing soldiers rather than defending territory. Several of the most important posts in and around the Indian Territory – Fort Scott, Fort Gibson, Fort Towson, and Fort Washita, among them – lacked palisades at the beginning of the Civil War.

Several “forts” – Coffee, Gibson, and Towson among them – were abandoned by the United States Army prior to the Civil War and turned over to the Indian Nation on which the land stood. In 1861 Fort Coffee was a boy’s academy for the Chickasaw Nation, Fort Towson was the capitol building of the Choctaw Nation, and Fort Gibson a civilian town in the Cherokee Nation, briefly renamed Keetoowah.

Others, such as Forts Arbuckle, Cobb, and Washita, were used to run Indian Agencies that supplied tribes with Federal provisions, or held garrisons that protected the Five Civilized Tribes from the incursions of the more primitive Plains Indians. These forts, abandoned by their Union garrisons in May 1861, were quickly reoccupied by both Texas and Confederate Indian troops.

These collections of permanent buildings were about the only places where supplies could be safely stored, troops assembled and housed, and administrative functions performed. Fort Gibson housed the brigade in which George Campbell served until its capture by the Union in 1863. Thereafter it served as the focus of Union activities in the Indian Territory. Later in the war George Campbell and his regiment lived at Fort Coffee for part of the time, in barracks that in peacetime had been the dormitory for the boys that attended the boarding school that it had become.

A major source of food for the armies in the Indian Territory was beef from the herds that the Indians had run on their lands. Cattle belonging to enemy Indians were fair game. Cattle belonging to allied Indians had to be paid for. However, if you dressed the beef in the field – as shown here – embarrassing brands showing that allied Indians owned it disappeared. (Potter Collection)

Besides Fort Gibson, the Mackay Salt Works was the main post for the Union Army in the Indian Territory. It was then one of the main local sources of salt, which was critical for preserving food. East of Fort Gibson, and north of the Arkansas River, it housed the 2nd Indian Home Guard Regiment to which Watcher belonged from 1863 through to the end of the war.

The value of Fort Gibson lay in its buildings, like this one. The Commissary Building, built in 1845, sheltered the supplies that an army needed for its continued existence. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Garrison life was an ordeal for Indian soldiers. It was dull. At Mackay Salt Works Watcher mounted guard. He tended his gear and animals. Rather than barracks or cabins, Watcher, and the soldiers of the 2nd Home Guard, slept in army tents. Since they were there more or less permanently, they stockaded the sides of the tents with walls of split logs, and put in a wooden floor of split logs, which reduced the mud in the tents, and kept them warmer in the cold winter months.

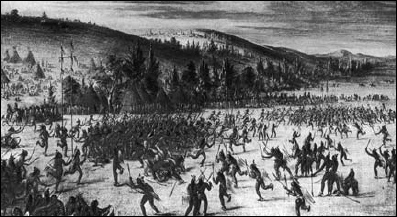

The only distractions were ball games: a version of what would become lacrosse was played as avidly by members of the Civilized Tribes as baseball would be played by GIs during World War II. The ball-and-stick games began as part of the Indians’ religion, but by the 1860s were played for secular amusement more than as religious ritual. The decline of a religious aspect did not reduce Indians’ pursuit of this sport. They participated with a passion similar to the grip that high school football exerts today in small-town Texas and Oklahoma.

Nor was interest limited to Indians. When the Union Indians were in Kansas these games became a spectator event for nearby whites, both civilian and military. William Coffin, a Kansas Indian Agent, described one game in Kansas, where he watched “one hundred men stripped stark naked, except for a breech clout, the most athletic, muscular and powerful men, too, that I ever looked upon all exerting themselves to the utmost stretch of human exertion, with the wildest and most exciting shouts of triumph, defiance and determination.”

Mostly though, you waited. “Hurry up and wait” was never a desirable state for a frontiersman, whether Indian or white, yet garrison duty was mostly that. Indian troops either became demoralized or deserted between battles.

The 2nd Home Guard lost nearly half its strength in July 1862 after capturing Fort Gibson, and settling in for less than a month of garrison duty. The Osage Indians in that regiment – 180 of them – left to go buffalo hunting. Many of the full-blooded Cherokees, those that were members of the Kee-too-wah Society, decided that the US Army was too slow a means of punishing the Confederate Cherokees. Scores left to seek private revenge against those that had driven them off their lands.

Others left to check on their farms and ranches. They had joined the army to recover their homesteads, and felt that while there was no active fighting, they should be free to put things to right at their homes. They planned to return when they had restored their farms.

The sport of the Civilized Nations was a ball and stick game that developed into the modern game of lacrosse. This Catlain painting shows a ball game that took place near Fort Gibson, prior to the Civil War. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

This constant turnover of soldiers occurred in units on both sides of the conflict. The Union’s 1st Indian Home Guard never counted more than 800 men on any one day of the Civil War, yet 3,274 Indians enlisted in the regiment between May 1862 and May 1865. The Confederate 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Regiment – the first Indian Regiment raised and the longest-lived unit – was lucky to muster 800 men on a good day, and probably fielded less than 250 on an average day. Yet 2,470 different men enlisted in the regiment over its lifetime.

Some of the turnover was due to casualties, but most was due to individual soldiers taking a casual view of enlistment. The three Union Indian regiments enrolled 8,003 different individuals during their existence. 1,018 Indians died while serving in these units, but only 2,400 men were present when the regiments mustered out in May 1865. The remaining 4,600 members simply disappeared. In December 1863, Cooper’s Brigade – which included the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Regiment – had only 659 men present out of the 6,244 names listed on the muster rolls.

Turnover diminished as the war progressed. In many cases soldiers stayed with their units because their farms and ranches had ceased to exist. Indians’ involvement in the Civil War resulted in civil wars within tribes. The Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole tribes each split into pro-Union and pro-Confederate factions, which coalesced into two formal governments for each of these tribes. Each faction believed it represented their tribe’s legitimate government and that the other government stood for that tribe’s traitors and turncoats.

Extremists on both sides destroyed private property belonging to those in the other faction. When the Union Army evacuated the Indian Territory in August 1862, Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross and other Cherokees who abjured the Confederate alliance and declared for the Union, joined the retreating Northern army. Rose Cottage – Ross’s substantial three-story mansion in Park Hill – was burned to the ground after Confederate Cherokees reoccupied Park Hill, along with many other homes owned by Union Cherokees. Watcher’s cabin was among them.

When the Union retook Park Hill in 1863, homes owned by Confederate Cherokees were torched. The damage was deliberate and planned. The few buildings standing in Park Hill by the end of the war were those owned by whites – the Indian Agents who chose to live with the Cherokee aristocracy, who stood outside the tribal feuds.

The process was repeated throughout the Indian Territory. Initially arsonists were individual Indians angered by others in their tribe who they regarded as traitors. The destruction grew until few private buildings remained standing between the Kansas border and the Red River. Destroying a rival’s property was encouraged by a quirk of Indian law. Indians did not own the land that their property sat upon – only the buildings and improvements. After George Campbell’s Union neighbors burned down his family’s plantation, they could have then gone before the Union Cherokee government to ask that the Campbell land be re-allotted to them as it was now “unimproved.”

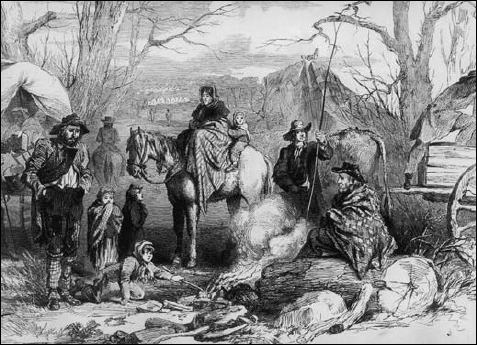

The Civil War on the western frontier was both uncompromising and personal, creating vast numbers of civilian refugees. This Frank Leslie plate shows one such family that was typical of both whites and Indians that had to flee their homes. (Potter Collection)

How much arson was motivated by greed and how much by hate is hard to say. The seeds of the civil wars within the Indian Nations went back for decades, even prior to removal to the Indian Territory. The anger felt by both sides went much deeper than the simple issues of whether one favored the Confederacy or the Union.

The loss of civilian housing reduced Indians of both sides to dependency upon the military for food and shelter. Wealthy Confederate Indians, like the Campbells, moved their families to northern Texas, along a strip in Choctaw and Chickasaw territory near the Red River. Wealthy Union Indians were denied even that much sanctuary as the guerrilla fighting in Kansas and Missouri made the northern border regions unsafe. All they could do was stay near military posts in Kansas and the Indian Territory with their poorer tribesmen.

Supply dominated the lives of everyone in the region, from the commanding generals to the ordinary soldiers, like George and Watcher, and even the civilians in the area – their families and friends. For both George and Watcher life, even in garrison, meant hunger.

The food was boring, if usually regular – at least for the soldiers. In garrison Watcher got rations issued to a Union soldier. On good days this was 20oz of fresh beef, probably taken from a steer formerly owned by an Indian. Had Watcher been at Fort Gibson, with its bake ovens, he would have received 22oz of soft bread. Instead, he received the prescribed alternative: 1lb of hard bread (called hard tack). He might also get his daily share of dried beans – about 6oz, cooked – and 1lb of coffee once every two weeks.

Indians were not alone in burning civilian buildings. White Confederate partisans raided and burned Lawrence, Kansas on August 21, 1863. They were seeking, but failed to catch, abolitionist James Layne. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

This provided 3,000 calories per day, which was enough for an active man. Often, the garrison had to go on short rations, as the Confederates frequently cut the supply lines. For their families and the other Indian civilians, both Confederate and Union, the inability to harvest crops or move sufficient food into the Indian Territory meant starvation. Years later, Mrs. C.B. Kagy recalled that her mother was one of the civilian Indians living around Fort Gibson during the Civil War: “Citizens had nothing more than bread [provided by Fort Gibson] and wild onions fried in tallow to eat.” Soldiers with families would pass part of their ration to parents, wives, or children if they were living nearby.

George should have received the same rations as Watcher – the Confederacy used the same scale as the Union – but supply to the Indian Territory was unreliable. Most of George’s food came from local sources, as long as there were some. His meals had greater variety if less certainty than Watcher’s. Corn pone was frequently substituted for bread, and fresh pork for fresh beef. Or else they would eat Union rations captured during raids on supply trains.

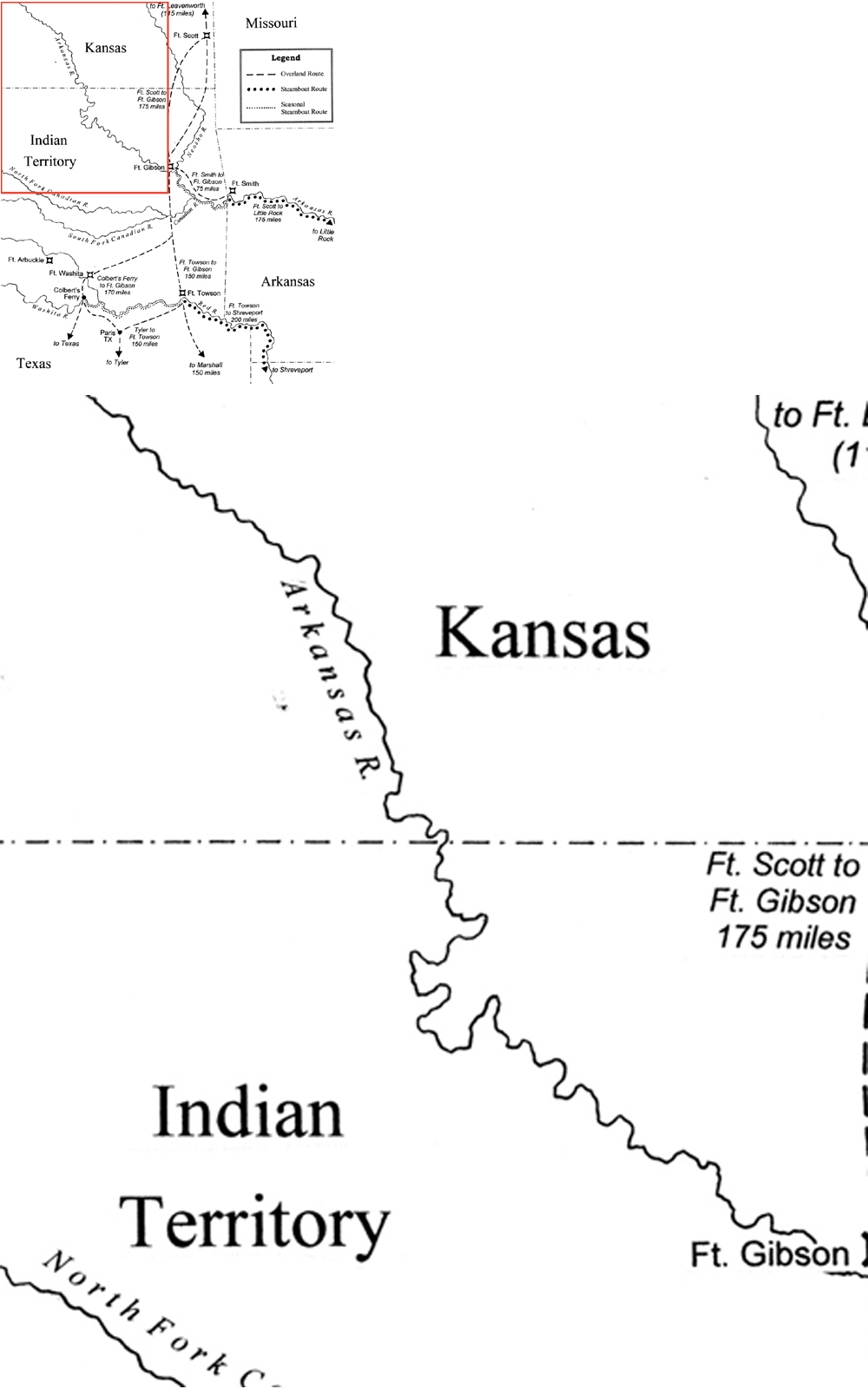

The Indians were permitted to inhabit the Indian Territory partly because it was out of the way and hard to reach. There were no railroads. Steamboats only reached the periphery of the lands ceded to the Indians. Fort Gibson could only be reached by steamboat in late spring and early summer, when the water level was highest. Fort Smith, on the Arkansas border, was normally the head of navigation for the Arkansas River. The Red River, the boundary between Texas and the Indian Territory, could be reliably navigated as far west as Fort Towson.

The portions of the Indian Territory occupied by the Five Civilized Tribes was civilized by 19th-century standards. Yet this was still a frontier colony, dependent upon imports for the maintenance of civilization. The Campbell family grew their own food, producing a surplus for export. They spun their own cloth from cotton they raised, and they purchased leather goods from neighbors. Their tools, however, were imported. Everything from the paper for the local printing presses, to the engine parts that ran Indian-owned steamboats came from elsewhere. Watcher McDonald, as a fur trapper and subsistence farmer, depended upon imports for his gunpowder, traps, and shot.

From Fort Smith on the southeastern corner of the Choctaw Nation, goods had to be moved by wagon or pack train. It was 150 miles from the Red River to Fort Gibson, and roughly 75 miles from Fort Smith to Fort Gibson. It was 160 miles from Fort Washita to Fort Gibson, and 80 miles from Fort Washita to Fort Towson.

Reaching Fort Gibson from Fort Scott, Kansas required an overland trek of 175 miles. Fort Scott could not be reached by steamboat or railroad during the Civil War. Goods that reached Fort Gibson from Fort Scott first had to travel overland an additional 115 miles from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, or via Independence, Missouri, to reach Fort Scott. Under normal circumstances it could take a wagon two weeks to travel from the Missouri River to Fort Gibson.

Civil War supply lines to the Indian Territory.

In peacetime a wagonload or two of manufactured goods – including powder and shot – met the demands of a farming community for a year. But the war strained transportation networks throughout the United States, as both sides geared up for a war economy. The Indians were totally dependent upon what was shipped to them – and little got through. Richmond’s orders to supply the Indians were ignored by the surrounding states until the needs of their own units were satisfied.

Soon other factors choked the flow of goods to the Indian Territory. The Unionists captured the Mississippi watershed, cutting steamboat traffic. New Orleans’ fall in April 1862 severed the Indian Territory’s only water route to the outside world. The Union took Memphis, Tennessee, in June 1862, eliminating the Indians’ access to Tennessee’s manufacturing center. Little Rock, Arkansas, fell in 1863, further isolating the Indian Territory from the South.

By 1863 it was impossible to grow crops in the Creek and Cherokee Nations. By then, George’s family had fled to Texas. The Indians’ herds of cattle and horses were disappearing, gathered by whites from Texas and Kansas to meet both armies’ need for food and mounts. It took an overland journey of 150 miles to reach Marshall, Texas, or Tyler, Texas – the two northernmost Texas towns manufacturing military goods. These towns were 200 miles from ports on the Texas coast.

In 1864 the war moved into the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations, making it impossible to raise food anywhere in the Five Civilized Nations. All foodstuffs had to be imported – enough to feed the civilian population as well as military personnel.

Both sides became reliant upon supply trains. Watcher helped guard trains against the raids of the Confederates. Every piece of clothing or ammunition issued to Watcher started from Fort Leavenworth and followed a long road to Fort Gibson. Food such as grain, flour, or beef could be gathered around Fort Scott, and only had to move 175 miles. The bake ovens at Fort Scott and Fort Gibson were feeding most of the Union Indian soldiers and their families that were in the Indian Territory by the start of 1864.

Without railroads or steamboats, supplies – both Union and Confederate – had to be transported by wagons once past the boundaries of the Indian Territory. The limitation of draft animals meant that both sides could supply troops only as far as Fort Gibson. (Potter Collection)

The oxen and horses pulling the wagons had to be fed. The land between Fort Scott and Fort Gibson was a natural hayfield, but what was a simple task in peacetime became a challenge during the war. Hay-gathering parties became targets, and requiring armed escorts. George once helped set the prairie north of the Verdigris River on fire to burn the hay before Union forces could gather it.

In the face of such opposition, supply trains brought only a minimum of the supplies required to keep the Union garrisons in Fort Gibson clothed, armed, and fed – with barely enough extra food to keep Indian civilians from starving. Many died – leaving Watcher grateful that he was an orphan, without the responsibilities that so many of his comrades had of keeping their families fed.