Why did the Indians of the Indian Territory enlist to fight in the Civil War? The first wave joined for the glory and the adventure, or to defend their homeland. This group joined Confederate regiments. The next wave joined for revenge or to reclaim lost lands. Initially, this group consisted of Indians that joined the Union regiments. Eventually, as the tides of war in the Indian Territory shifted from the Confederates to the Union, revenge and reconquest became a major motivation for Indians joining Confederate units. Finally, Indians ended up enlisting in the Indian regiments of both sides because they had no choice. Neutrality became impossible. Survival – for both the males of fighting age and their families – required a choice between the North or the South.

The Five Civilized Nations were in a period of flux at the start of the Civil War, in the process of adopting white customs, attitudes, and technology into their traditional ways of life. The transition was a rocky one, further complicated by a forced move to the Indian Territory, which some Indians opposed while others acquiesced. A large group – like George Campbell’s immediate family – chose to assimilate white ways. These were often the Indians that had intermarried with whites or blacks. Others, including George’s cousin Watcher McDonald, preferred the traditional ways. The Civil War focused these different approaches into open conflict, as a lens concentrates sunlight into flame.

The Choctaw and Chickasaw had almost completely assimilated into European lifestyles and the lives they led were little different from most frontier whites. The other three tribes still had large elements that wished to continue their lives in the manner of their fathers and grandfathers, as small-holding farmers raising enough to feed their family with a small surplus to trade for the necessities that they could not produce themselves such as manufactured goods, gunpowder, and firearms. They saw plantation farming with chattel slavery and an emphasis on material acquisition as a threat to that lifestyle.

To the assimilationist Indians, the traditional Indians were the problem. It was the old story of the converted being the most fervent advocates of a position. They felt the traditional ways stood in the way of progress and acceptance by the United States. Acceptance of their tribe – whether Chickasaw, Choctaw, or Cherokee – as equals to the whites, not second-class or second-best, was important to them. One of the reasons the Confederate alliance was so seductive was that – on paper – the Confederacy offered equality. The Indian Nations were given voting representation in the Confederate assembly. The Confederacy offered to pay the Indians the relocation monies still owed by the Federal government.

Trade routes flowed to New Orleans, linking the Civilized Tribes economically to the Confederacy. The plantation aristocracy that ran the politics of the tribes was also emotionally linked to the Old South. After the Union defeat at Bull Run, followed by the Confederate victory at Wilson’s Creek – a battlefield in Missouri so close to the Indian Territory that a battalion of Cherokees participated – establishment of the Confederacy seemed an accomplished fact. The promised prize was enough to lead the assimilated Indians – those that had adopted the whites’ technologies and attitudes – to declare for the Confederacy.

The traditionalist Indians rejected this alliance for three major reasons. First, they did not want to become involved in white wars. When they had – during the War of 1812, and the Mexican–American War – things had deteriorated for the Indians, even those allied with the United States. Next, the citizens of the Confederate states were the ones whose demands had led to exile in the Indian Territory. The citizens of Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Mississippi had forced them west of the Mississippi River. Texans and Arkansans had chased them out of those states.

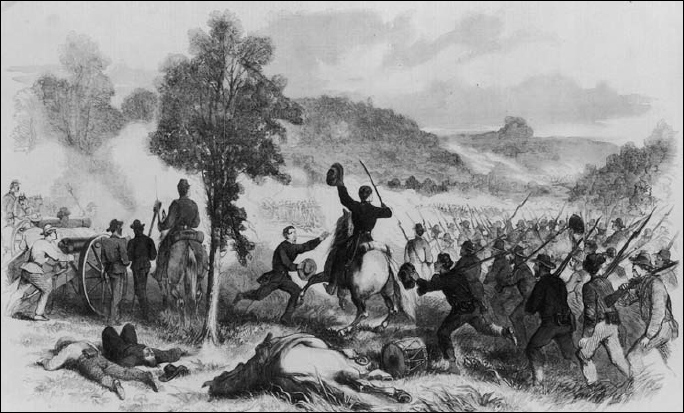

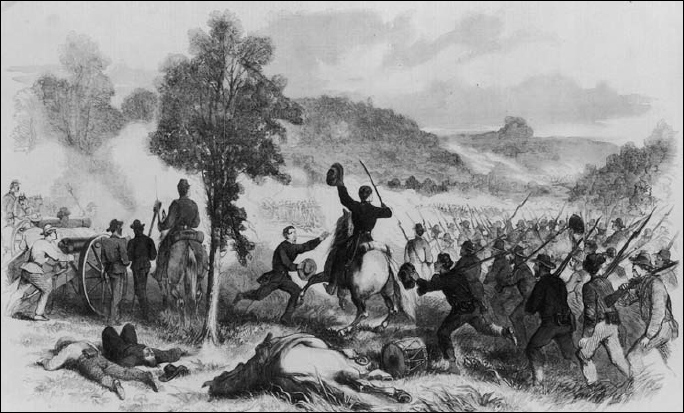

Combined with news of Bull Run, the Union defeat at Wilson’s Creek, Arkansas, in August 1861 convinced the Civilized Tribes that the Confederacy was going to win. It forced the Cherokee Nation to abandon neutrality and declare for the Confederacy, which cut off the loyal Creeks and Seminoles from Kansas. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Finally, the United States government had a habit of winning wars, and punishing tribes that opposed them. Indians that had fought the United States – men like Opothleyohola and the Seminole chief Billy Bowlegs – tended to view the Confederacy as yet another tribe, albeit white, that was going to be crushed by the Federal government, just as the Creeks and Seminoles had.

The traditional Indians felt neutrality was the best course, but their assimilated cousins blocked that option. The Indian alliance with the Confederacy was made for political advantage, not survival. Forcing the traditionalists to choose sides turned it into a war for survival for the Indians opposed to the Confederacy, which in turn transformed the Civil War in the Indian Territory into a war to the knife, a total war.

The two major Indian secret societies, the Kee-too-wah and the Knights of the Golden Circle, reflected the cultural divide among the Indians.

A Baptist minister who was a full-blooded Cherokee organized the Kee-too-wah in 1859. Membership at that time was limited to full-blooded Cherokees. The mission of the Kee-too-wah society was to protect traditional Cherokee ways (as modified by Christianity) and defend the interests of the full-blooded members of the Cherokee Nation.

Members identified themselves by wearing crossed straight pins (or a single straight pin) on the left lapel or left breast of their hunting jackets. Alternatively, they would pin a corn shuck to their clothing or plait a shuck in their hair. In daylight, members greeted each other by drawing their left lapel forward and rightward across the heart when passing. In the dark, one member would issue a challenge saying “Tahlequah – who are you?” The proper response was, “I am Kee-too-wah’s son!”

The society adopted the American flag as its emblem, underscoring an anti-secessionist attitude. The society became abolitionist early in its existence, viewing chattel slavery as incompatible with both Christianity and the traditional Cherokee way of life. As such, the society was tremendously threatening to the Cherokee propertied class. After the Cherokee Nation allied with the Confederacy, members of Kee-too-wah were viewed with suspicion, and many were driven out of the Indian Territory as Northern sympathizers.

While many members of the Kee-too-wah initially enlisted in the Indian Home Guard in 1862, many became impatient when the Northern government failed – in the members’ eyes – to adequately punish Cherokees that supported secession. These Kee-too-wah members deserted the army to be free to take what they felt was appropriate action more directly. Along with abolitionist Jayhawkers from Kansas, they provided a Northern counterpoint to the terrorism conducted by Southern bushwackers. All of these groups contributed significantly to the brutality of the Civil War in the Western frontier.

The Knights of the Golden Circle were the Confederate counterpart to the Kee-too-wah. The Knights of the Golden Circle had its roots in the Masonic tradition. Founded in 1854 in Cincinnati, Ohio, it quickly spread south, with a significant number of lodges in Texas and Arkansas. By 1861 there were several chapters in the Indian Territory made up of mixed-blood Indians and local whites. Stand Watie was a Knight. So was Albert Pike, the former Indian Agent from Arkansas who convinced the Indian Nations to join the Confederacy. At the time of the Civil War the Knights held a pro-slavery and, frankly, racist position.

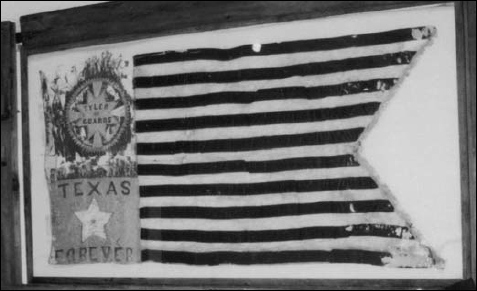

The Tyler Guards, whose battle flag is shown, were part of the 3rd Texas Cavalry, a white unit that fought in the Indian Territory. The emblem in the jack portion of the flag, in which the words “Tyler Guards” appears, is that of the Knights of the Golden Circle. (Smith County Historical Society)

While membership by Indians in an organization that espoused racial superiority may seem surprising, it underscores the degree to which the wealthy Indians thought themselves part of the planter aristocracy. The Choctaw Nation then had one of the most restrictive black codes in the United States. The Civilized Tribes began as warrior nations. The Cherokee and Choctaw were highly ethnocentric, believing themselves superior to all other peoples white, black or Indian.

Whites, by virtue of martial prowess were conceded to be equals, to be emulated. This was especially true of the planter aristocracy, whose views on warfare and class mirrored those of these Indians. But blacks were regarded as a servant class. From the first contact with people of the Old World, the Choctaw, Cherokee, and Chickasaw had seen the blacks as servile laborers, inferiors that were incapable of being warriors.

The situation was more complicated among the Creeks, and especially the Seminoles (who had intermarried with runaway slaves to form a new tribe), but these nations were viewed as the more backward of the five. Additionally, the Seminole was both the smallest of the Five Civilized Nations, and the last to find a place in the Indian Territory.

The Indian members of the Knights of the Golden Circle were equally contemptuous of their full-blooded cousins, dehumanizing them by calling them “Pins” or “Shucks” (from the emblems of the Kee-too-wah).

At the battle of Honey Springs the Confederate Indians attacked, despite having damp gunpowder. Having discovered that their opponents had a black regiment, they believed that “niggers” would not fight, and the “Shucks” would fight poorly. The Confederates, both Indian and white Texans, wanted to force a battle before the blacks ran away. Instead, the blacks waited, held their line, and blasted the Confederate cavalry charge apart with disciplined rifle fire.

Yet anti-black sentiment was never far from the surface of the Confederate Indians. White soldiers were permitted to surrender, but after Honey Springs this was a nicety denied to black soldiers, who were usually killed out of hand. Sometimes a Confederate victory concluded with a hunt for surviving black soldiers.

By 1861 most of the Indians in the Civilized Tribes were Christian. The conversion was sincere and by the end of the 1850s there were enough Indian ministers that the missionary societies were withdrawing their missions because these Indians were no longer viewed as a heathen people. Even the two principal Indian secret societies, the Knights of the Golden Circle and the Kee-too-wah, were based on Christian foundations. The individual nations built churches for their communities, and missionaries were running most Indian schools. Christianity was at the center of the Indians’ society, and a major motivation in their activities.

Some Indians, especially traditionalists, still maintained the old religions. Each tribe had a traditional religion that was animist in nature. They shared characteristics: they believed in a creator, or Great Spirit; they attempted to put the believers in harmony with the world through a variety of rites, ceremonies, and actions, and explained natural phenomena by anthropomorphizing them. For example, in the traditional Cherokee religion, the Sun and the Moon were sister and brother, and the animals arranged in tribes, just like humans.

Many of the activities associated with Indians in war, including wearing war paint, and holding a ceremonial dance before a battle, were called for by their traditional religion, and were religious in nature. Whether Christian or traditional believers, the Indian participants in the Civil War often fell back on the old beliefs in times of stress.

Before the First Indian Expedition started, soldiers in the two Indian Home Guard Regiments held the rituals prescribed by the old religious traditions. This involved consuming the black drink – a purgative that induced vomiting, and a night of ritual dancing, followed by a plunge in the river. The ritual was supposed to make the participant bulletproof. With inadequate food, the inferior equipment issued to them, and the unenthusiastic attitude of the Union Army to these troops, even skeptical Indians probably felt that if the ceremony offered even a small advantage it was worth taking.

While most of the Indians belonging to the Civilized Nations were Christian, some clung to the old traditions, partly out of belief, but mostly due to tradition. Before the First Indian Expedition left camp, members of the Indian regiments held a war dance. (Potter Collection)

Nor were the more assimilated Southern Indians immune to the lure of such protections. George Washington Grayson related in his memoirs that members of his company had “great faith in certain Indian war medicines said to afford protection against the casualties of battle.” Grayson declined the offer of such a treatment, as he wanted to prove that he was courageous enough to take part in battle without such protection.