The Indians of the Civilized Nations, like their frontier white counterparts, were first-rate fighters, but untrained soldiers. They knew how to hunt and shoot, and used these peacetime skills in combat. Their battles resembled large-scale hunting parties, with other humans as quarry, and the quarry fighting back.

The three battles fought in the Opothleyohola campaign of 1861 illustrate this best. Fought between traditionalist Indians loyal to the United States and Confederate Indians with the assistance of two regiments of Texas frontiersmen who were culturally similar to their Indian allies, the tactics used by both sides were those familiar to hunters.

The Union Indians set up ambushes in strongpoints that were functionally similar to duck blinds or deer stands used in Texas and Oklahoma today. They hid the rifleman from his quarry – in this case the Confederate troops – and also provided protection against enemy fire. The Confederates set up skirmish lines that moved forward like a line of drivers, beating the ground to flush their quarry – the Union loyalists.

At Round Mountain in November 1861, Texas cavalry met sentries from Opothleyohola’s force. When the Texas company, some 40 men, charged, the Indians fell back, disappearing into timber lining Walnut Creek, near the Red Fork of the Arkansas River. When the Texans pursued, other Indians, hidden in the wood, opened fire, driving the Texans back. The Union Indians chased these scouts until both scouts and the Union Indians reached the main Confederate force. Both sides fought dismounted, lying or kneeling as cover afforded.

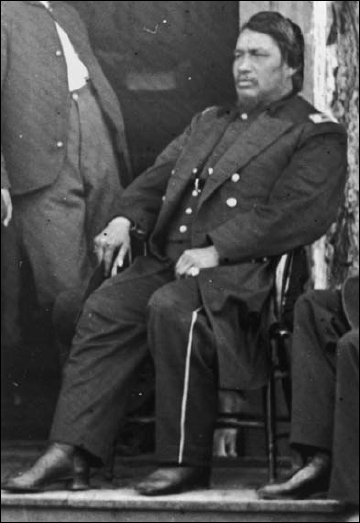

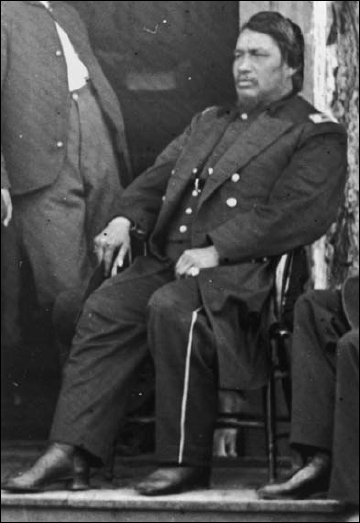

A Seneca Indian, Ely Parker became the highest-ranking Indian in the Union Army during the Civil War. An engineering officer, he was on General Grant’s staff in 1865, when this photograph was taken. After the war he became a general, and President Grant’s Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

The Union Indians began flanking the Confederates, moving through cover like hunters stalking prey. While the Confederates with roughly 1,400 men – mostly Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws – probably outnumbered the Union forces, Douglas Cooper, commanding the Confederates, thought he was outnumbered and fell back. The battle continued until after dark, when the Union Indians – their families escaping during the battle – slipped away.

Casualties were light on both sides. This was the first Indian Territory battle of the war and like most inexperienced troops both sides shot high. Additionally, the targets for both sides were under cover.

The battle of Chusto-talasah (or Bird Creek) on December 9 followed the pattern of the first fight. The Union Indians fortified an encampment along Bird Creek, and a Confederate force of 2,000 of the Cherokee Drew’s Mounted Rifles with an additional Texas cavalry regiment (the 4th Texas Cavalry) attacked.

The pro-Union forces fired from cover, while the Confederate center, led by the Creek regiment, dismounted and crawled forward until they were close enough to charge the Union works. In hand-to-hand fighting akin to traditional Indian warfare, the Confederate Creeks drove the Union Indians from the timber barricade on the Confederate left. Knives, tomahawks, and butted rifles decided the outcome.

While Texas cavalry covered the right, a 100-man company from the Choctaw and Chickasaw regiment charged on horseback to a cabin and corncrib anchoring the center of the Union line, dismounted and took the cabin. Once both sides had fired their rifles, that battle also became a hand-to-hand fight.

As before, the Confederates held the field, but the pro-Union Indians slipped away. Again, casualties were light on both sides, despite the fury, fewer than three dozen men in total were killed. Opothleyohola stated that nine of his force was killed. Cooper reported 15 dead and 37 wounded on his side.

Opothleyohola’s column then was in the Cherokee Nation, sheltered by James McDaniel, a Cherokee unhappy with the Confederate alliance. He was not the only Cherokee that disliked the alliance. The day before Chusto-talasah 400 Cherokees in Drew’s Regiment were persuaded to change sides. Most were full-bloods, who had enlisted to protect the Indian Territory from invaders, not to fight other Indians, especially the full-blood Creek and Seminole traditionalists that made up Opothleyohola’s band.

Chusto-talasah flushed Watcher McDonald from neutrality. As Opothleyohola’s column fled past his cabin, Watcher gave them what food he could spare. Called to account for supporting “traitors,” Watcher took his horse, his rifle, and what possessions he could carry and slipped north.

This pattern was repeated at Chustenahalan on December 26, 1861, which was fought near Tulsey Town (today’s Tulsa). The pro-Union Indians picked a good defensive position, which the Confederate forces attacked. By this time, the loyalists were running low on ammunition. Additionally, their families were worn out by six weeks’ flight in winter conditions and had abandoned many of the supply wagons. The result was a rout. Reinforced still further and with additional troops from Texas and Arkansas, the Confederates scattered Opothleyohola’s army. They captured “160 women and children, 20 Negroes, 30 wagons, 70 yoke of cattle, about 500 Indian horses, several hundred head of cattle, 100 sheep, and a great quantity of property.” Over 300 of the pro-Union warriors were slain on the battlefield.

Confederate prisoner of war camps for Indian Territory prisoners were grim places. Frontier shortages meant both food and clothing was difficult to obtain. Additionally, captured Indians were assumed to be traitors, and kept in bleak conditions such as those pictured here. (Potter Collection)

These battles represent the final conflicts between Indians fought in their traditional style of warfare. Opothleyohola’s force was a traditional Indian army, with men following war leaders they knew and trusted. Although the Confederate Indians were in formally organized units, their officers were men who would have been war leaders a generation earlier. The tactics were more akin to those seen in a fight between Indians – or the bushwhacking and jayhawking that took place in “Bleeding Kansas” – than Civil War battles.

In this campaign Indians on both sides fought in war paint – just as their ancestors had at Horseshoe Bend in 1812. The Indians went into combat shouting war cries. Private James Kearly, of the 6th Texas Cavalry, stated that as his Indian allies charged into the pro-Union Indians, “they slapped their sides and gobbled like turkeys.” Captain H.L. Taylor, of the 3rd Texas Cavalry, reported that his opponents made “all sorts of noises, such as crowing, cackling, and yells.”

The Indians also scalped dead opponents during these battles. Private Edward Folsum, of the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Regiment, in a postwar memoir claimed that he “got the scalp” of two dead foes at the Chusto-talasah. White soldiers in the Trans-Mississippi, especially those belonging to irregular bands on both sides, could be just as barbaric in mutilating their opponents. Texas irregulars were also accused of scalping the enemy dead. Scalping, especially when carried out on white soldiers in battles where the Indians participated, reinforced white prejudices that these Indians, even if Christian and educated, were still savages.

The next campaign in which Indian troops fought illustrated both their strengths and weaknesses as soldiers. An Indian brigade fought at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, in March 1862. Like white militia units Indian soldiers could fight tenaciously in defense of their homes, but often proved reluctant warriors when moved out of their own neighborhood. One Indian regiment at Pea Ridge – the Cherokee Drew’s Mounted Rifles – fell into that category. They fought tentatively on the first day of the battle, and then withdrew on the second. Several other Indian regiments, including one Creek regiment and the Choctaw and Chickasaw regiments either refused to leave the Indian Territory, or moved too slowly to reach the scene before the battle was decided.

Indians also assisted the Union Army in Virginia. This photograph shows some of the Pawmunkey Indians that served as scouts and river pilots on the James River. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Even when the Indian troops proved eager fighters, they were not always efficient soldiers. Chilly McIntosh’s Creek Regiment and the Cherokee Watie’s Mounted Rifles welcomed the Pea Ridge campaign as an opportunity to show that they were worthwhile allies of the Confederacy. They made a colorful appearance. A member of the 1st Missouri Brigade wrote, “They came riding into camp yelling forth a wild war whoop that startled the army. Their faces were painted, for they were on the ‘warpath.’”

During the battle the two Cherokee regiments – perhaps 1,000-strong, along with 200 Texas cavalry – charged and took a three-gun Union artillery battery. They swept out of the woods, knocking down a fence in front of them, and charged across the field, swarming over a three-gun battery before the startled crews could respond. It was a magnificent feat of arms. The artillerymen fled with their horses, leaving the guns behind unspiked.

At this point experienced, disciplined troops would have established security, or continued the pursuit of their fleeing enemy. The Cherokees did neither. Instead they milled around the guns they had taken, examining their prizes and collecting souvenirs. Others exalted in having survived, yelling and whooping victoriously. It was a normal reaction for green troops after a first experience of combat, and one that was often repeated in that first year of war.

Some wasted time scalping the dead. Of the 25 bodies later found around the guns, eight had been scalped. Drew’s full-bloods blamed Watie’s mixed-bloods, who in turn blamed the full-bloods. Some Union survivors claimed that that they saw the Texans scalping bodies. All three groups had probably been guilty to some degree.

The failure of their officers to take charge of the situation cost them the fruits of their victory. While they were celebrating, Union officers deployed two additional batteries and supporting infantry to retake the guns. When the Union batteries opened fire, the soldiers of the Confederate brigade panicked and fled back to the woods where they had started, leaving the three guns of the battery behind.

Panic is the appropriate word for what happened. Less than an hour earlier these troops boldly charged across an open field to take the battery. Disorganized by victory, they were startled into retreat by an unexpected bombardment. Once in the trees, they steadied, dismounting and returning fire from the cover of woods. They fought hard for the rest of the afternoon, but never recovered the guns.

It was a pattern that recurred throughout the rest of the war by Indian troops on both sides of the conflict in the Indian Territory. When they could fight using terrain for cover, they fought tenaciously and held ground doggedly. In a charge – unless faced by a steady and disciplined infantry line – they were invincible. From ambush they were deadly. They were almost arrogantly confident when attacking. But they lacked the training to fight in a line in the open, and the discipline to conduct a rearguard action. As a result, whether the Indian regiments were the best troops available – or the worst – depended entirely on the situation to which they were committed.

Pea Ridge also highlighted another aspect of the Indians in combat. They hated artillery fire, and avoided artillery when they could. While in Kansas trying to interest the whites in an expedition to retake the Indian Territory, Opothleyohola told the United States Army “you must bring us down wagons that shoot.” Muskogee lacked a word for artillery, so the chief couched his request in a transliteration of the native term for cannon, but he knew that whoever brought artillery would have an advantage on the battlefield.

The Indians’ attitude was sensible and shared by frontier white units that fought on both sides in the Indian Territory. Artillery was the battlefield’s wholesale killer. But it limited the effectiveness of Indian troops. When a battery opened fire, the side receiving fire took it as a signal to find a new direction to attack, ruining an attack’s momentum. A few guns resolutely handled gave a column protection disproportionate to their actual battlefield effectiveness.

The battle of Pea Ridge was the first major appearance of organized Indian units outside of the Indian Territory. Their presence was one of the factors that led Union leaders to authorize the formation of the Union Indian regiments. (Author’s collection)

The capture and destruction of the steamboat J.R.Williams illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of the Indian soldiers on both sides of the conflict. The J.R.Williams was transporting supplies from Fort Smith in Arkansas to Fort Gibson in the Cherokee Nation. The steamboat carried no munitions, but it carried enough food and clothing to free the Union from its dependence on the overland supply line route from Fort Scott for a year, and this in turn would have enabled the troops guarding that line to conduct offensive operations against Confederate-controlled sections of the Indian Territory.

Stand Watie planned and executed an ambush of the boat. One month before the water on the Arkansas River was expected to rise high enough to let the boat reach Fort Gibson, Watie began scouting the riverbank seeking the perfect spot to launch an ambush. He found a sharp bend where the channel came close to the southern bank, 50 miles from Fort Smith. Then, he sent scouts to watch the boat. The day before it was apparent that the J.R.Williams was going to sail, he sent three small field pieces and 400 men to the ambush site. He also sent the 200 men of the Cherokee 2nd Mounted Rifles to a spot halfway between the ambush and Fort Smith, to slow any relief force sent to recover the boat.

The ambush was executed perfectly. The artillery caught the boat in a crossfire. Rifle fire from the Indians hidden along the banks threw the Union guard – a company from the 12th Kansas Infantry – into disorder. The pilot steering the boat ran it aground in the ensuing panic. The boat’s crew surrendered to the Indians, while the guard swam to the north bank, and then walked to Fort Smith, where they raised the alarm. The next day two regiments were sent from Fort Smith to retake the boat, but their progress slowed to a crawl when they encountered the 2nd Mounted Rifles. Firing from cover, they stalled the Union advance.

Indiscipline then undid Watie’s plans. As they unloaded the boat, the food and supplies aboard the J.R.Williams proved to be too much of a temptation for Watie’s troops. Their families were starving, and the men loaded up their ponies with food and clothing, then melted away, taking a few days’ unofficial leave to take the windfall to their families. By dark Watie’s 400 men had shrunk to less than 40.

Artillery gave the North its margin of victory. Light field pieces, such as this one, permitted the Northern armies to dominate battles and protect supply trains. The Confederate forces in the Indian Territory almost always had fewer artillery pieces than their opponents – if they had any at all. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

The 2nd Indian Home Guard Regiment was stationed at the Mackay Salt Works, east of Fort Gibson. This was close enough to hear the cannon fire, and a party of Indians was sent to investigate. They found three members of the boat’s guard force who had become separated from the rest of their company. The scouts returned with their intelligence. The commander of the 2nd Indian Home Guard reacted promptly. He sent 200 men, one third of his force, to rescue the boat.

An advance guard – perhaps two dozen men – pushed ahead of the main body, reaching the steamboat by mid-morning. Rather than wait for the rest of the party to come up these Union Indians ran a bluff. Hiding along the riverbank, they began to shoot at the Confederate troops on the opposite bank, maintaining as heavy a fire as possible to give the impression that they were a much larger force.

It worked. The wagons from Boggy Depot had not arrived. There were a handful of Confederate troops available. Colonel W.P. Adair, the Cherokee commander of the 2nd Mounted Rifles, reported that he was being hard-pressed by the force from Fort Gibson. Now a new force of unknown size was pressing from the opposite bank. Watie ordered that the steamboat should be burned.

Although steamboats could occasionally reach Fort Gibson, Fort Smith, Arkansas, was the effective head of navigation for the Arkansas River. The US Army built a stockaded fort at that spot prior to the Civil War, which proved to be one of the keys to supplying the Indian Territory. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

The aftermath of the battle illustrated another weakness of Indian troops. They hated picket duty – especially in a retreat. To cover the withdrawal of his artillery, Stand Watie directed Lt. George Grayson to “furnish a sentinel of a suitable number of trusty men to remain and stand watch until sun down … in case the enemy appeared in pursuit … to give the alarm.” Grayson further stated in his memoirs “… as I had expected, I failed to get a single man to remain.” With the pride of youth, Grayson maintained the picket single-handed until sundown, one scared youth upholding what he felt to be the honor of his regiment and his tribe.

Combat was a more personal matter for the Indians than it would be for most of the soldiers in the Civil War. Both George and Watcher would have known some of the men that they fought against, and sometimes killed. Legus Perryman, who served as a sergeant in the 1st Indian Home Guard, remarked about one skirmish, “… we slew about 30 men of the rebels and lost two of our own. Among the dead rebels we found one we knew by name, Walter Mellon.”

As raiders they could be invincible. In September 1864, General Gano took 2,000 men (including 800 men from Stand Watie’s brigade) on a sweep into the northern half of the Indian Territory. Watie’s force was made up of five Indian regiments: two Creek, two Cherokee, and one Seminole. By this stage in the war the Confederate Indian regiments had shrunk to between 125 to 200 men each, but the men that remained were veterans and fighters.

They swept into unprepared Union positions like a cyclone. On September 16, the column destroyed a hay party near the Verdigris River. They moved up to Cabin Creek, and in the pre-dawn hours of the 19th attacked a supply train there. Major Henry Hopkins of the 2nd Kansas Cavalry reported, “At 1 o’clock the enemy opened with artillery and small arms and moved upon my lines with a yell.” George Grayson continues the account from the Confederate side: “The enemy did not hold out long but began giving way before our fire, when our Seminole contingent made a rush to deliver an attack in the right, where no fighting had been done.”

The civilian teamsters panicked, and attempted to flee. In the process they broke wagon tongues, and stampeded oxen teams. Some of the few that did get moving drove their wagons off a cliff, destroying the wagons and killing the drivers. The Union troops – which included 140 Cherokees and Creeks from the 2nd and 3rd Indian Home Guard – fell back into a stockade near the train, but evacuated after the Confederate troops began shelling it. The Union responded in force the next day, but by then Confederates had destroyed the train: 300 wagons loaded with supplies for Fort Gibson.

The raiders continued their sweep, finally arriving back in Confederate lines two weeks later. In tow they had some 80 captured wagons. The raid’s commander, Richard M. Gano, described the results: “We were out fourteen days, marched over 400 miles, killed 97, wounded many, captured 111 prisoners, burned 6,000 tons of hay, and all the reapers and mowers – destroyed altogether from Federals $1,500,000 of property, bringing safely into our lines nearly one-third of that amount (estimated in greenbacks). Our total loss was 6 killed, 48 wounded.”

Whatever flaws they had as soldiers, most of which were due to lack of training, the Indians were undoubtedly fighters.