WRITING ABOUT ARCHITECTURE

Architecture Briefs is a Princeton Architectural Press series that addresses a variety of single topics of interest to architecture students and professionals. Field-specific and technical information, ranging from hand-drawn to digital methods, are presented in a user-friendly manner alongside basics of architectural thought, design, and construction. The series familiarizes readers with the concepts and skills necessary to successfully translate ideas into built form.

ALSO IN THE ARCHITECTURE BRIEF SERIES:

ARCHITECTS DRAW

SUE FERGUSON GUSSOW

ISBN 978-1-56898-740-8

ARCHITECTURAL LIGHTING:

DESIGNING WITH LIGHT AND SPACE

HERVE DESCOTTES, CECILIA E. RAMOS

ISBN 978-1-56898-938-9

ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHY THE DIGITAL WAY

GERRY KOPELOW

ISBN 978-1-56898-697-5

BUILDING ENVELOPES: AN INTEGRATED APPROACH

JENNY LOVELL

ISBN 978-1-56898-818-4

DIGITAL FABRICATIONS: ARCHITECTURAL AND MATERIAL TECHNIQUES

LISA IWAMOTO

ISBN 978-1-56898-790-3

ETHICS FOR ARCHITECTS: 50 DILEMMAS

OF PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE

THOMAS FISHER

ISBN 978-1-56898-946-4

MATERIAL STRATEGIES: INNOVATIVE APPLICATIONS IN ARCHITECTURE

BLAINE BROWNELL

ISBN 978-1-56898-986-0

MODEL MAKING

MEGAN WERNER

ISBN 978-1-56898-870-2

OLD BUILDING, NEW DESIGN: ARCHITECTURAL

TRANSFORMATIONS

CHARLES BLOSZIES

ISBN 978-1-61689-035-3

PHILOSOPHY FOR ARCHITECTS

BRANKO MITROVIC’

ISBN 978-1-56898-994-5

WRITING

ABOUT

ARCHITECTURE

MASTERING THE LANGUAGE OF BUILDINGS AND CITIES

With photographs by Jeremy M. Lange

PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS, NEW YORK

PUBLISHED BY

PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS

37 EAST SEVENTH STREET

NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003

FOR A FREE CATALOG OF BOOKS, CALL 1-800-722-6657. VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.PAPRESS.COM.

© 2012 ALEXANDRA LANGE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

15 14 13 12 4 3 2 1 FIRST EDITION

NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE USED OR REPRODUCED IN ANY MANNER WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER, EXCEPT IN THE CONTEXT OF REVIEWS.

EVERY REASONABLE ATTEMPT HAS BEEN MADE TO IDENTIFY OWNERS OF COPYRIGHT. ERRORS OR OMISSIONS WILL BE CORRECTED IN SUBSEQUENT EDITIONS.

ALL IMAGES © JEREMY M. LANGE

EXCEPT PAGE 44 © FREESTOCKPHOTOS.ES.

PAGES 21–28. “HOUSE OF GLASS” REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF THE GINA MACCOBY LITERARY AGENCY. COPYRIGHT © 1952 BY ELIZABETH M. MORSS AND JAMES G. MORSS. THIS ESSAY WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE NEW YORKER.

PAGES 147–58. FROM THE DEATH AND LIFE OF GREAT AMERICAN CITIES BY JANE JACOBS, COPYRIGHT © 1961, 1989 BY JANE JACOBS. USED BY PERMISSION OF RANDOM HOUSE, INC.

EDITOR: LINDA LEE

DESIGNER PRINT EDITION: DEB WOOD

SPECIAL THANKS TO: BREE ANNE APPERLEY, SARA BADER, NICK BEATTY, NICOLA BEDNAREK BROWER, JANET BEHNING, FANNIE BUSHIN, MEGAN CAREY, CARINA CHA, RUSSELL FERNANDEZ, JAN HAUX, DIANE LEVINSON, JENNIFER LIPPERT, GINA MORROW, JOHN MYERS, KATHARINE MYERS, MARGARET ROGALSKI, DAN SIMON, ANDREW STEPANIAN, PAUL WAGNER, AND JOSEPH WESTON OF PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS —KEVIN C. LIPPERT, PUBLISHER

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

LANGE, ALEXANDRA.

WRITING ABOUT ARCHITECTURE: MASTERING THE LANGUAGE OF BUILDINGS AND CITIES / ALEXANDRA LANGE ; WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY JEREMY M. LANGE. — 1ST ED.

P. CM. — (ARCHITECTURE BRIEF SERIES)

ISBN 978-1-61689-053-7 (PBK. : ALK. PAPER)

ISBN 978-1-61689-113-8 (DIGITAL)

1. ARCHITECTURAL CRITICISM. I. LANGE, JEREMY M. II. TITLE. III. TITLE: MASTERING THE LANGUAGE OF BUILDINGS AND CITIES.

NA2599.5.L36 2012

720.1—DC23

2011032750

INTRODUCTION

How to Be an

Architecture

Critic

BUILDINGS ARE EVERYWHERE, large and small, ugly and beautiful, ambitious and dumb. We walk among them and live inside them but are largely passive dwellers in cities of towers, houses, open spaces, and shops we had no hand in creating. But we are their best audience. Owners, clients, and residents come and go, but architecture lives on, acting a role in the life of the city and its citizens long after the original players are gone. Architecture critics can praise and pick on new designs, but their readership has lately been too limited. We talk (in person, on blogs) about homes as investments, building sites as opportunities, unsold condominiums as an economic disaster, but all of that real-estate chatter sidesteps the physical reality of projects built and unbuilt. Rather than just talking about money, we should also be talking about height and bulk, style and sustainability, openness of architecture and of process. Design is not the icing on the cake but what makes architecture out of buildings and the places we want to live and eat and shop rather than avoid. Instead of less talk, what we need are more critics—citizen critics—equipped with the desire and the vocabulary to remake the city.

There are times when city dwellers have been roused from passivity. Disaster (Ground Zero) and personal affront (NIMBYism) make protestors out of us all, but we are rarely roused by the day-to-day, brick-by-brick additions that have the most power to change our environment. We know what we already like but not how to describe it, or how to change it, or how to change our minds. We need to learn how to read a building, an urban plan, and a developer’s rendering, and to see where critique might make a difference.

This is a handbook that demonstrates how critics look at those buildings, parks, and plans, and shows how anyone can follow in the footsteps of those writers. It is based on courses in architecture criticism I teach at New York University and the School of Visual Arts—classes that simultaneously offer a foundational history of twentieth-century criticism and lessons in doing it yourself.

In the courses and in this book, I connect the reader and the writer, the citizen and the critic, in two ways. First and foremost by reading and comparing exemplary pieces of critical writing. Each chapter in this book is preceded by a complete essay or lengthy excerpt from a piece of critical writing about a different building or urban type: Lewis Mumford on skyscrapers, Herbert Muschamp on museums, Michael Sorkin on preservation, Charles W. Moore on the monument, Frederick Law Olmsted on parks, Jane Jacobs on cities. In the text that follows the essay, there is a close reading of that essay, discussing the specific questions raised by the critic about the type and the methods he or she uses to raise those questions.

There is no one right way to write architecture criticism, but the critics discussed in this book all get it right in different ways. An understanding of their style, editorial judgment, and mode of argument can help future critics to get it right as well. Digging into Olmsted’s principles of park design, for example, one gains a sense of the history the landscape architect is working against or within. Reading Karrie Jacobs’s review of the far more recent High Line, one sees those principles considered and rejected in the contemporary park. There is continuity between Central Park and the High Line, but it takes a deeper knowledge of American park design to see it.

After reading the original text and the accompanying discussion, the critic should have the tools to discuss the building type and be able to choose the history, method, and elements that seem most relevant. The critical essay is typically brief (in a newspaper, approximately twelve hundred words), so one must limit the questions asked and answered. Quotations from others discussing the same type or even the same building illustrate the vast array of possible themes available to a critic. The theme is the narrative line in any piece of criticism, an idea about the architecture or architect introduced at the beginning of the essay, bolstered by evidence in the body of the text, and returned to at the end. It gives a critique shape and allows the critic to impose his or her personality on the project in question. (The italicized terms are ones to which I will return in the text—key considerations for any piece of critical writing.)

Three critics, standing side-by-side, looking at the same wall, can have completely different things to say about that wall without ever disagreeing. One might consider the wall’s material, comparing it to other structures that use marble, glass, or metal in similar ways. The other might ignore its physical aspect and discuss instead how it separates building from street, circulation from offices, public from private. Yet another might imagine the wall as a backdrop for interpersonal drama. In teaching it is often hard for me to repress my own opinions about a building or plan, but I try always to make it clear: there is no right answer about whether a building is good or bad, beautiful or ugly, accessible or imposing. The critic needs to define terms, choose a theme, then evaluate the architecture within those guidelines. Knowing something about the larger critical history of the type will be essential to choosing appropriate parameters.

Another way critics define their agenda is by selecting an approach. By the end of the book, the reader will have been exposed to four major critical approaches of the latter half of the twentieth century. I list them here but will discuss them in more detail in the chapters. The first is the formal approach. Formal, in art historical terminology, does not mean damask napkins and silver but a primary emphasis on the visual—the building or object’s form. Both Huxtable and Mumford come to their judgments through intense looking. They write about what they see from the street—the building’s organization, materials, connections. They literally walk you through the building, describing and picking at it as they go, suggesting improvements. This approach offers one of the easiest methods of organization: the walk-through, as exemplified by Mumford’s tour of Lever House, examined in chapter 1. Organization is the structure of the review: Is it a three-part argument? A stroll in the park? A visual analysis from steps to spire? Because we are writing about a visual art, there is often a parallel between the literary and the architectonic organization.

The second approach is experiential, as created and defined by Muschamp, the late New York Times critic. Muschamp is also descriptive in his writing, but he expresses the way a building makes him (and by extension, the reader) feel. His reviews can start anywhere in a building, even at the airport of the city in which the building stands (as in his review of the Guggenheim Bilbao, discussed in chapter 2), and often mix in other media—movies, art, books, poetry—in order to make the emotional connection between architecture and reader.

The third approach is historical, which is primarily identifiable in the work of the present-day New Yorker architecture critic Paul Goldberger. He is interested in the architect’s career and in fitting buildings within that (limited) framework. A Goldberger review may be as much about personality and presence on the world stage as it is about a building, but it also offers a sense of context missing from other critics’ work. One is left with a sense of completeness, of having a thorough survey.

The final critical approach, seen in the criticism of Sorkin (chapter 3) and more broadly in the career of Jacobs (chapter 6) is that of the activist. Their first questions are not visual or experiential: Who loses? Who wins? These critics feel that they are the defenders of the city and of the people, and analyze projects primarily for economic and social benefits. Sorkin, in particular, knows the value of a good kicker: a last line that makes you laugh, however sourly.

These approaches are, like themes, only starting points. As the internet opens up more avenues for criticism, the pie may be sliced more thinly, generating a sustainable critic, an accessibility critic, and a feminist critic of architecture. Some have found the formal approach wanting in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, feeling that it can remove buildings from their cities and place too much emphasis on materials and appearances above their role in the urban landscape. I disagree—at least as the approach is practiced by Huxtable and Mumford—but it is worth considering that some approaches may be played out.

In my courses, after reading and analyzing the work of critics, I lead my students on field trips to new buildings, parks, even information centers; the students all review the field-trip subject. They then read and critique each others’ reviews in preparation for an in-class workshop. They are evaluated on the revision of their original review, written with my input as well as that of their classmates. It is in personally writing a piece of criticism where abstract lessons about theme, organization, and approach really take hold. And this aspect of the course is trickier to put in book form.

The course alternates between reading sessions, field trips, and writing workshops because the three activities create a feedback loop. Familiarity with exemplary models for criticism (the readings) is essential to be able to write good criticism but spending too much time in the classroom does not a critic make. At the end of each chapter is a checklist of questions meant to facilitate the kinds of conversations that occur during workshop sessions. The questions help guide the writer to be constructive in his or her criticism and also suggest directions that await exploration. What do we ask of our parks today that we did not in the past? How do skyscrapers operate as billboards in the digital age? How can blogs take up the mantle of Jacobs? Asking and answering these questions it is harder than it seems. That’s why you have to go out and do it.

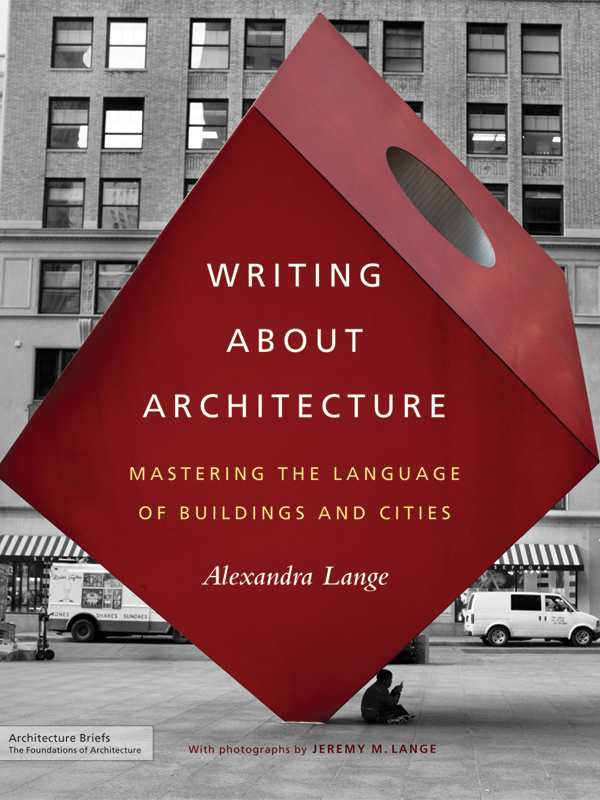

So how do you read a building? As with any craft, start with the best example you can think of and pick it apart until you see how it was done. The piece I return to has a title as applicable to the text as it is to the spaces the text describes: “Sometimes We Do It Right,” written by Huxtable and published in the New York Times on March 31, 1968. Huxtable’s review of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s (SOM) 1967 Marine Midland Bank Building at 140 Broadway in Lower Manhattan describes the miraculous way architecture and public art of different eras can come together to create a great urban space.

Huxtable reviews the office tower, but only in passing, since for 95 percent of New Yorkers, its importance will only ever be as a backdrop for Isamu Noguchi’s Red Cube sculpture. She only skims the surfaces of all its neighbors, noting their varied materials, historical styles, and how their presence alters the streetscape. The sidewalks and open spaces are her main concern. Noguchi’s cube claims the plaza that is Marine Midland’s front yard, but there are views around the cube and through the downtown canyons that are equally striking. The contrast of solid and void is what makes this corner “right” and what makes any city right.

What differentiates one corner, one neighborhood, or one city from another is the ratio of building to open space: the heights of Midtown versus the low brownstones of Brooklyn in New York or the peaks of central Lake Shore Drive versus the residential neighborhoods to the north and south in Chicago. As Huxtable writes, “Space is meaningless without scale, containment, boundaries and direction.” Space needs as much shaping as the act of building, and in this review she balances the need for architecture and the need for open space, writing from the perspective of the pedestrian and adding a sense of history to the everyday experience of walking the streets.

In a way, the structure of this book imitates her balance between solid and void. In the first three chapters the critics evaluate specific buildings. In the next three they look at the places around those buildings—monuments, parks and neighborhoods—an effort that requires less discussion of architectural style and more of the movements of people.

Few practitioners of criticism meant to be critics. Criticism happened to them, through a combination of luck, outrage, and moments in cities when building outstripped sense. There are strong parallels between the beginning of Huxtable’s career as critic in the late 1950s and the building (and architecture) boom of the early twenty-first century. In both cases a certain amount of bedazzlement prevailed as glittering towers replaced brick-and-stucco neighborhoods. There were (and are) great pieces of architecture, but the speed of construction also fostered a culture of knock-offs—good ideas repeated in inhospitable places or with subpar materials.

Huxtable started her career as an assistant curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in the 1940s. She received a Fulbright in 1950 to study modern architecture in Italy and subsequently wrote a book on architect and engineer Pier Luigi Nervi (Pier Luigi Nervi, published 1960). As one of few trained historians of the modern movement, she noticed gaps in the New York Times’s architecture coverage. Her sense of connoisseurship, distinguishing the best from the second-rate, served her from the very beginning of her career. In 1959 she wrote the Times editors a long letter in response to their positive review of a photography show on a modernist housing project in Caracas, Venezuela. Apparently, it looked great, but Huxtable had been there and had seen that the beautiful buildings did not work for their inhabitants. Her letter (printed in full) showed knowledge, passion, and a critical voice, and the paper hired her.

In 1963 Huxtable became the New York Times’s first architecture critic. She held that position, with variations in title, until 1982 and won a Pulitzer Prize in 1970. What is charming and replicable about her first ten years as reviewer is the immediacy of her experience of so many great works of modern architecture: the Whitney Museum, the CBS Building, the glass canyons of Park Avenue, the marble plazas of Lincoln Center. Reading her pieces (collected in the wonderfully and evocatively named Kicked A Building Lately? [1976] and Will They Ever Finish Bruckner Boulevard? [1970]), it is clear that her first loyalty is to the citizens of New York and that she thinks they deserve better.

Before she does anything else in “Sometimes We Do It Right,” Huxtable describes what she sees. This may seem rather simplistic, but it is a step many critics skip today, since most reviews come with a photograph or slideshow. These writers want to leap over the visual to get to the big picture: the architect’s genius, the international trend at work, the latent theory in the practice. Huxtable gives the reader explicit directions about where to stand and candidly states what she notices, offering immediate insight into reading a building or the city. First, you have to be there. Critiquing renderings is often a necessity, but you cannot gain insight into what works unless you have seen it, touched it, and experienced it in person. Here is the formal approach exemplified: she stands on the sidewalk and points you east.

For a demonstration of New York at its physical best, go to Broadway between Cedar and Liberty Streets and face east. You will be standing in front of a new building at 140 Broadway....

Look to your left (Liberty Street) and you will see the small turn-of-the-century French pastry in creamy, classically-detailed stone that houses the neighboring Chamber of Commerce. To your right (Cedar Street) is a stone-faced building of the first great skyscraper period (pre-World War I through the 1930’s).

Move on, toward the East River, following the travertine plaza that flows elegantly on either side of the slender new shaft, noting how well the block size of the marble under foot scales the space.

If you were to literally follow in her footsteps (as I hope you will), you would see just how much is not described in the text. The critic is an editor: to make a visual argument, you have to cut out much of what you see. You also have to comment on what you do see, as concisely as possible. Calling the Chamber of Commerce a “French pastry” is funny, conjuring up (for me) the idea of a croissant wedged between dour towers or artist Claes Oldenburg’s 1965 Proposed Colossal Monument for Park Avenue, a Good Humor bar of sixty stories to replace the unloved Pan Am Building at the south end of the avenue. The Chamber of Commerce looks just as much like a crumpet today, with its fruity garlands and elaborate Ionic capitals, and still provides an excellent contrast in personality to both Marine Midland and the 1915 Equitable Building by Ernest R. Graham across Cedar Street.

Huxtable’s allusion to the first skyscraper period is a historical reference that demonstrates her authority (she didn’t see her first skyscraper yesterday) without interrupting the present-day flow. The “stone-faced” Equitable is a building distinguished less for its neoclassical wrapper than for its bulk: it fills its block from side to side and corner to corner. Its monstrous presence spurred the 1916 zoning resolution that sprinkled Manhattan’s streets with tapered towers until it was revised in the 1960s to allow for slabs-with-plazas like Marine Midland. Equitable still looms larger than Marine Midland, despite being many floors shorter, because the open space around the later tower makes it seem slimmer—the rezoning was right.

The plaza at the south side of Marine Midland is edged with a planter and a series of benches, leading around the corner of Cedar Street to the lobby. From there, the plaza continues east toward the Chase Manhattan Bank Building, designed by Gordon Bunshaft for SOM seven years before he worked on Marine Midland. Your eye is led to and through the glass atrium that surrounds Chase’s elevator core, as if you could see past it and on down Cedar Street. But your feet must stop. Nassau Street lies between 140 Broadway and Chase, and you can’t move from one building’s plaza to that of the next one without cutting between parked cars, crossing the street, going up some steps. A huge Chase logo looks like the end of the line.

But the open space continues, even with this barrier [Nassau Street]. Closing it [Marine Midland’s plaza] and facing Chase’s gleaming 60-story tower across Liberty Street is the stony vastness of the 1924 Federal Reserve Building by York and Sawyer, its superscaled, cut limestone, Strozzi-type Florentine façade making a powerful play against Chase’s bright aluminum and glass.

Huxtable stops here for a moment of sheer visual revelry. Her words are active, giving the architecture a sense of movement—powerful play, gleaming, stony—that allows a reader to feel what she feels for a moment. Most buildings do not move, but they have impact, and transmitting that impact verbally can fire the imaginations of people who might just have walked on by. These adjectives give a taste of the rhetorical explosion to come in the criticism of Muschamp. Huxtable has always been more reserved, but manages to give the buildings she describes personality through well-chosen descriptors. The Federal Reserve Building reads as stone wallpaper, so vast is its side, so crisply incised are its mortar joints. It is a model for many of the postmodern office buildings built after Marine Midland, but its solidity and strength are no longer achievable.

Huxtable then deploys another critic’s trick, particularly useful for the positive review, overstatement:

This small segment of New York compares in effect and elegance with any celebrated Renaissance plaza or Baroque vista. The scale of the buildings, the use of open space, the views revealed or suggested, the contrasts of architectural style and material, of sculpted stone against satin-smooth metal and glass, the visible change and continuity of New York’s remarkable skyscraper history, the brilliant accent of the poised Noguchi cube—color, size, style, mass, space, light, dark, solids, voids, highs and lows—all are just right.

It is hard to know if she really thinks this happenstance plaza beats those in Rome and harder to believe many would agree with her. But her enthusiasm is infectious and carries the reader to her larger point: cities are perpetually reinventing themselves. We may prefer the uniformly ancient beauties of the Capitoline Hill, but that is not a viable model for the contemporary city. Happenstance, accretion, a change in neighbors can combine to create new beauty at any moment. The critic would not be doing her job if she did not think today could be as good as the past. And Huxtable, deeply involved in the preservation movement in New York City, would not be doing her job if she did not recognize the qualities of older buildings as well as the latest ones.

Her enthusiasm is as much for the historic as it is for Noguchi’s then-boldly-anarchic cube, which seems much larger in person than in photographs. That cube is an interesting footnote. Today the corporate sculpture of the 1960s, much of it by Noguchi, rarely warrants a second glance, so imitated has it been by lesser sculptors, in lesser plazas. “Plop art” was the dismissive term coined by architect James Wines in 1969 for large, geometric, and abstract sculptures in corporate settings, suggesting that its commissioning and placement were too easy. It was as if the corporate owners said to the people of New York, “Here you go, some Art.” But bad imitations should not lessen the impact of superior examples, and as Huxtable points out, the cube is just the right size, shape, and color, set just the right distance from the building.

One section of the review comes close to straight-up architecture criticism as we know it: the critic, the new building, an assessment:

Not the least contribution is the new building, for which Gordon Bunshaft was partner-in-charge at S.O.M. One Forty Broadway is a “skin” building; the kind of flat, sheer, curtain wall that it has become chic to reject....

It is New York’s ultimate skin building. The wall is held unrelentingly flat; there are no tricks with projecting or extended mullions; thin or flush, they are used only to divide the window glass....The quiet assurance of this building makes even Chase look a little gaudy.

But this judgment of the curtain wall is only a fraction of what she has to say—she’s rewritten her assignment on the fly, because the new building is the least of her concerns. In fact, Huxtable never says the building is good or bad but describes it in terms that make her appreciation clear. She gets inside the architecture by focusing almost exclusively on the curtain wall, as the curtain wall is what sets this box apart from its neighbors and the curtain wall is all that most members of the public will ever see of the building.

Ever since Bunshaft designed Lever House uptown on Park Avenue in 1952, New York’s corporations had been involved in an endless game of curtain-wall one-upmanship. Thus, when Huxtable talks about flatness, she’s describing the latest iteration in a search for new looks for the glass-and-steel tower. As Huxtable notes, by 1968 the public was growing as restless with this aesthetic as they were with plop art, but Marine Midland is a superior example of its type. The sense of collective urban ego present in the postwar building boom that produced so many skin buildings never happened in New York’s last building boom, with the possible exception of the 2005 Hearst Tower by Foster + Partners. Huxtable sounds a prescient, doleful note in her conclusion: “What next? Probably destruction. One ill-conceived neighboring plaza will kill this carefully calculated channel of related space and buildings....It only takes one opening in the wrong place, one ‘bonus’ space placed according to current zoning (read ‘business’) practice to ruin it all.”

“Sometimes We Do It Right” includes a number of features that I would urge readers of this book to use in their own writing. One, description: She sets the scene, and her theme, through opening paragraphs that bring the city vividly to mind. Two, history: She demonstrates that the skyscraper is not something new (via her neighborhood tour) and that Marine Midland is part of a lineage (via her discussion of curtain walls). These glancing references establish her expertise (she knows more about this topic than most) and also sidestep a common problem: a gee-whiz awe at the latest and greatest model in the line. Three, drama: Many people consider architecture boring. The first line of defense against this charge is making the connection for the reader between how architecture looks and how it makes one feel. It’s not just a building but a speaking artifact. Finally, the Point: Huxtable has twelve hundred words with which to make her point. When you read her review, you feel at all times that she knows exactly where it is going. She has chosen the three areas she wants to highlight—the surroundings, the plaza, the building’s skin—and she makes them with all deliberate speed. (If you have selected a theme and a mode of organization, and if you know what your critical approach is, having a point shouldn’t be hard. Leave out more than you leave in.)

Huxtable’s modest, carefully articulated rallying cry is left to the end: “Space is meaningless without scale, containment, boundaries and direction....This is planning. It is the opposite of non-planning, or the normal patterns of New York development. See and savor it now, because it is carelessly disposed of.” Her method is developmental, leading the reader to agreement rather than telling them what they will learn at the outset. Remember Huxtable’s subtlety as you read the other examples in this book, and consider what they have in common: visual language, authority, argument. Huxtable is asking you to look at what is around the architecture as much as the building in question, calling your attention to what is really important to get right.

The more built environment people see and savor, the more they act like architecture critics, the better they will be able to recognize good planning and become advocates for it. What this book teaches is how to recognize, articulate, and argue for such continuing moments of beauty. The first step is following in the footsteps of the masters. The second is writing about the city you want to see.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

Click on the bold text in the essay sections to read the corresponding discussion of the essay in the chapter. Clicking on the underlined text will bring you back to the essay.