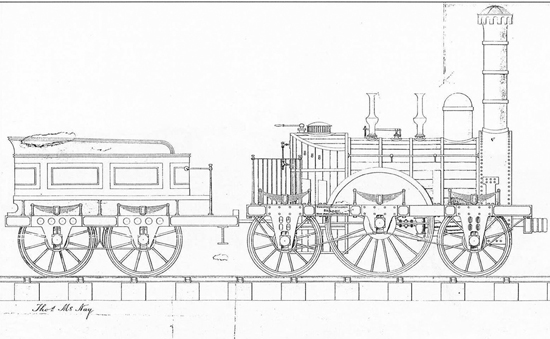

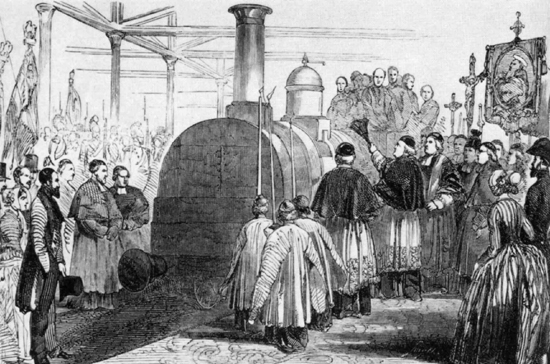

Timothy Hackworth’s locomotive built for the first Russian railway in 1836

The Russians can reasonably claim the honour of being the first to show an interest in British railway building with the visit of the Grand Duke Nicholas to the Middleton Colliery Railway. He was, at any rate, sufficiently impressed to order a model of Matthew Murray’s locomotive. When he later became Tsar Nicholas I he made it clear that his enthusiasm for railways was undimmed. It was, indeed, widely rumoured that the Tsar had sent spies to England to report on new industrial processes.

In many ways Russia was the least likely country to dash forward into the railway age. Firstly, it was a land divided, part Asian, part European, with a ruling class that yearned for the sophistication of French culture, but wished to combine it with the absolute rule of a feudal court. Although it was a country that valued science, the arts and industry, it depended economically on peasants and serfs. It also aspired to the new railways before it had even acquired roads that were better than muddy tracks. These filthy winding roads, virtually unusable in the atrocious northern winter, did as much to defeat Napoleon’s army as any deed of the Russian army. Nationalists and religious zealots of the Orthodox church feared the new system, while others, like the very pro-Western Prince Viazemsky, mythologized it.

Railroads have already annihilated, and in time shall completely annihilate, old previous means of transportation. Other powers, other steams have already long ago put out the fire of the winged horse, whose weighted hoof has cut off the life-giving flow that has quenched the thirst of so many gracious and poetic generations.

This was a very long way from the realities of railway life among the coalfields of north-east England. But Russia had its pragmatists as well as its dreamers.

In the 1820s, the Cherepanov family was running a factory making machine tools, and they became interested in using steam power. E.A. Cherepanov was despatched to England to investigate how this could be done. He saw a number of machines, and came home confident enough to start building engines at the company’s own factory. In 1830 it was proposed that a steam railway should be built from a copper mine at Nizhni i Tagil in the Urals to the factory. As these were only two miles apart it is indicative of the state of the roads that this project was deemed worthwhile. This time it was M.E. Cherepanov’s turn to go to England and to inspect the ‘road steam engines’. In the 1820s steam engines were so widespread and had already been around for over a century, that no one minded the presence of an inquisitive foreigner. Steam locomotives were a very different matter. Robert Stephenson’s works were already beginning to build up an impressive export business, and uninvited visitors were not encouraged. Nevertheless, Cherepanov was able to see locomotives out on the track in normal service, even if he could not watch them being built. He was back home in 1833 confident he could build an engine on the Stephenson model. In fact he was to build two to fit a track laid out to the Russian gauge of 2 arshim 5 vershak, or approximately 5 ft. 5 inches. In 1836 the first train set off on its pioneering run. It may have looked remarkably like a Stephenson engine, but its performance was nowhere near as good. Cherepanov had not been able to get quite close enough to the original for that. For its first genuine line for freight and passenger traffic Russia had after all to turn to Britain for expertise and hardware.

Timothy Hackworth’s locomotive built for the first Russian railway in 1836

In spite of the British connection, it was an Austrian, Franz Anton von Gestner, who first appeared in Russia with plans for a mainline railway to run from Tsarokoe Selo, home of the Imperial Summer Palace, to St Petersburg. Although the engineer was Austrian, almost everything used on the line came from Britain. Although Russia already had a successful iron industry and could, no doubt, have supplied rails for the line, it was actually cheaper to order rails from Merthyr Tydfil and ship them to Russia than to bring them overland from the Urals. If ever there was an argument for a railway system in Russia then this was it.

A whole variety of orders was sent from Russia to England – everything from turntables to cattle trucks – but by far the most important items were the four locomotives. Two were supplied by the Robert Stephenson works at Newcastle, the other pair came from Timothy Hackworth’s works at Shildon on the Stockton & Darlington Railway. The Russians, perhaps realizing that an order specifying a gauge measured in arshim and vershak would pose problems in north-east England, settled instead for a six-foot gauge: a suitably Imperial measure. Later Russian lines were to be built to the more modest gauge of 5 ft. 6 inches.

Timothy Hackworth, having survived the disappointment of the Rainhill Trials, had established a successful locomotive building business. Like so many stories of railway builders in distant lands, there is more than a hint of Boys Own Paper heroics in the surviving papers relating to the Russian adventures of the Hackworth family.

The story begins prosaically enough with the first engine, costed out with nice exactness at £1,884 2s. 9¾d., to include the tender. It was a typical product of the Hackworth works of that time, 2-2-2 wheel arrangement, with five feet diameter drive wheels. The somewhat odd feature was the cylinders, which were 17 inches in diameter with a very short 9-inch stroke, a design feature that was to enjoy no more than a temporary vogue. The first engine was despatched in the care of Timothy’s seventeen-year-old son John, accompanied by the Shildon foreman George Thompson and a small team of erectors and fitters. John Hackworth’s overseas visit was not lacking in incident. He travelled in winter and had to make his way by sleigh from the only open Baltic port to St Petersburg. Young Hackworth recorded nonchalantly – as though such occurrences were commonplace in County Durham – that the whisky in their flasks froze and they were pursued by a pack of wolves. When they arrived they faced the confusing task of trying to instruct the Russians in the mysteries of the steam locomotive. Von Gestner’s men were simultaneously working on the track itself. At any one time a conversation might be held in English, Russian, Flemish or German.

The Tsar himself came to see the first trial of the engine, and told John Hackworth of his earlier visit to England. He was very flattering about the new engine, declaring that he ‘could not have conceived it possible so radical a change could have been effected within 20 years.’

The locomotive was not, however, without its problems. In the early days of British railways, locomotives were run on coke following a requirement first brought in on the Liverpool & Manchester that locomotives should ‘consume their own smoke’. In Russia, coal and wood were tried with poor results: log burning was a particularly spectacular failure, as a Vesuvius of sparks burst out of the chimney, blew back over passengers in open carriages and set their clothes on fire. Hence coke had to be imported from England. A more pressing problem, however, was the cold. On one occasion, the freezing conditions led one of the cylinders to crack. George Thompson simply set off for Moscow, a mere 600 miles away, had a pattern made from which a new cylinder was cast and bored, and then returned to St Petersburg where he fitted the new cylinder. The locomotive was put back to work.

Once the engine had been successfully put through its trials it was ready for public use, but not without an official blessing by the Orthodox church in the presence of the Tsar and his family. Water was collected from a nearby bog and poured into a golden censer, in a ring of a hundred hurdles, where it was sanctified by the immersion of a golden cross. While a choir sang, priests gave their blessings. Then, using a large brush, the holy water was dashed with great vigour in the form of a cross over each wheel of the locomotive and also, inadvertently, over John Hackworth on the footplate. After that, and including prayers for the safe passage of the Tsar and all his family, the new age of passenger transport in Russia was declared open.

As with many countries, Russia only needed help over the first difficult step before using her increasing knowledge and confidence to develop her own rail system. It was not an easy process, particularly the financing of lines. A system was arrived at which was to prove popular in many other parts of the world. The government guaranteed a minimum return on investors’ capital – in this case 4 per cent – and with this guarantee the stockbrokers, Harman and Co., were able to raise the money on the London market for the ambitious and expensive line from St Petersburg to Moscow.

In France the position was reversed. The French began railway building on their own account. The innovative engineer Marc Seguin designed a locomotive in 1828 for the Lyons & St Etienne Railway, though even Robert Stephenson & Co. was commissioned to produce it. However, enthusiasm for railways was slow to develop.

As early as 1833 Vignoles was surveying a line that would link London to Paris. That proved too ambitious for financiers to contemplate, so a more modest proposal was put forward for a purely French line from Paris to Dieppe, with a branch line to Rouen. The Minister of Public Instruction, Monsieur Thiers, visited England to look at the new railways, but declared himself horrified at such monstrosities and would do nothing at all to promote railway building in France. The banker, Charles Lafitte, was highly indignant at this lack of interest in the new transport system, and lashed out furiously, decrying the ‘dearth of capital, the mistrust of the inhabitants, the charlatanism of speculators’. He recruited the help of an English entrepreneur, Edward Blount, a man of many parts. He was political agent to the Duke of Norfolk, an advocate of reform and, most importantly, a man who had the confidence of financiers of the calibre of Rothschild and Montefiore. In 1839 they approached the French government for help with the London & Southampton Railway. This line was an obvious choice. The route was to depend for much of its traffic on the port of Southampton, and a cross-channel link to a railway at Dieppe was clearly very much in their interests. The French government was to subscribe 28 per cent of the total of £2 million capital and the rest was to be raised equally in London and Paris. The chairman of the company, W.J. Chaplin, one of the directors, William Reed, and the chief engineer Joseph Locke went to France, were satisfied with what they saw of the likely route and it was agreed that work would start on the Paris to Rouen section.

An early map of the railway from Paris to Rouen, featuring a viaduct across the Seine.

Locke had originally intended to use French contractors and French labour, but French contractors’ prices were unreasonably high, so the work was put out to tender in Britain. Thomas Brassey and William Mackenzie put in bids and agreed, probably wisely as neither had experience of working overseas, to combine forces and work as partners.

If Locke was unimpressed by French contractors, Brassey and Mackenzie took an equally poor view of the peasant labour of Normandy. There was an obvious answer, as Joseph Locke explained in his presidential address to the Institution of Civil Engineers, describing the departure of Brassey and Mackenzie for France.

Joseph Locke, the chief engineer, who worked on many of the early European railways.

Among the appliances carried by these gentlemen, there were none more striking or important than the navvies themselves. Following in the wake of their masters, when it was known that they had contracted for works in France, these men soon spread over Normandy, where they became objects of interest to the community, not only by the peculiarity of their dress, but by their uncouth size, habits, and manners; which formed so marked a contrast with those of the peasantry of that country. These men were generally employed in the most difficult and laborious work, and by that means earned larger wages than the rest of the men. Discarding the wooden shovels and basket-sized barrows of the Frenchmen, they used the tools which modern art had suggested, and which none but the most expert and robust could wield.

Brassey’s enthusiasm for the French venture was, it is said, helped by the fact that Mrs Brassey was fluent in the language, which was more than could be said for most of the British invasion, with its army of 5000 navvies. The British were expected to instruct their French counterparts, and Helps’ biography of Brassey contains some illuminating first-hand accounts of how the British set about this task.

They pointed to the earth to be moved, or the wagon to be filled, said the word ‘d-n’ emphatically, stamped their feet, and somehow or other instructions, thus conveyed, were generally comprehended by the foreigner.

Supervisors and others either made an effort to learn French or were given interpreters.

But among the navvies there grew up a language which could hardly be said to be either French or English; and which, in fact, must have resembled that strange compound (Pigeon English) which is spoken at Hong Kong by the Chinese … This composite language had its own forms and grammar; and it seems to have been made use of in other countries besides France; for afterwards there were young Savoyards who became quite skilled in the use of this particular language, and who were employed as cheap interpreters between the sub-contractors and the native workmen … On this railway between Paris and Rouen there were no fewer than eleven languages spoken on the works. The British spoke English; the Irish, Erse; the Highlanders, Gaelic; and the Welshmen, Welsh. Then there were French, Germans, Belgians, Dutch, Piedmontese, Spaniards, and Poles – all speaking their own language. There was only one Portuguese.

Language was not the only difference. For example, the British navvy expected decent accommodation, but the Germans ‘would put up with a barn, or anything’. Then there was the question of appearance. The well-established navvy was expected to wear the navvy ‘uniform’ and ‘scorned to adopt the habits or the dress of the people he lived amongst.’ Pay too separated the native French from the rest. A sub-contractor noted that when work started in 1841 the French were happy, not to say delighted, with the pay they were offered: ‘When we went there, a native labourer was paid one shilling a day; but when we began to pay them two francs and a half a day, they thought we were angels from heaven.’ The British inevitably earned more, twice as much at the start, simply because they were more skilled. In wagon-filling, it was estimated that an experienced navvy would lift 20 tons of earth to a height of around 6 feet in the course of one day. To watch a well-trained team at work in a cutting was to see physical prowess at its most impressive. One of Brassey’s time-keepers wrote,

I think as fine a spectacle as any man could witness, who is accustomed to look at work, is to see a cutting in full operation, with about twenty wagons being filled, every man at his post, and every man with his shirt open, working in the heat of the day, the gangers looking about, and everything going like clockwork. Such an exhibition of physical power attracted many French gentlemen, who came on to the cuttings at Paris and Rouen, and looking at these English workmen with astonishment, said, ‘Mon Dieu! les Anglais, comme ils travaillent!’ Another thing that called forth remark, was the complete silence that prevailed amongst the men. It was a fine sight to see the Englishmen that were there, with their muscular arms and hands hairy and brown.

Another area in which the British excelled was in the skilled and dangerous work of mining tunnels. Conditions were bad: the air was foul, men often worked soaked to the skin and it was no place for the faint-hearted: ‘At times you hear alarming creaking noises round you, the earth threatening to cave in and overwhelm the labourers.’ It took raw courage to crawl into tunnels where the timbers were already bending under the pressure of the earth and shore up the space while the old supports cracked around you.

British navvies had other less admirable traits. They discovered brandy, and drank it as they did the local wine – with predictable consequences. Pay days were always an excuse for a ‘few’ bottles to do the rounds. Otherwise, however, the men fitted in at least as well with the life of the French villagers as they had with their English counterparts.

Helps’ biography of Brassey gives the broad sweep of the life of railway builders in France in the 1840s. A more detailed picture emerges from the diaries and papers of his partner William Mackenzie and his younger brother, Edward. The two contractors established offices in France and Edward set up house there, bringing his family out to join him. He worked on the Paris to Rouen line right up to its opening, and then promptly went on to start work on the Rouen to Le Havre Railway in 1843.

They faced many problems. It was obviously in their interest, having brought their army over to France, to ensure that it was fully occupied. This was not always easy. Weather in January might make work impossible. On 10 January 1842, Edward noted in his diary: ‘Very few men at work, the Frost being so deep into the ground, in the afternoon Rhodes and I went to Mezieres. The men with great difficulty kept at work. Very cold.’ In the event, the weather got worse and nothing at all was done until the 17th. When the weather was favourable, work might be held up because the company had not completed the deeds for buying the land.

I left early, Turner with me, for Les Mureaux, met Worthington and a great gang of men being idle for want of possession of land. He went with me into the wood near Epone and pointed out where a small piece of land was got, and we commenced and cut out a gully. I then returned home to breakfast.

Delays could, however, be, a good deal more troublesome. In February 1843 he wrote,

I went to the Poissy end of the works where a gang of men were at work making up part of an embankment at that point, working to every disadvantage not to stop the ballasting from Poissy. This job might have been done six months ago but we were not allowed to break ground at that time.

A rather more common complaint received no more than the laconic jotting: ‘Very few men at work being pay Monday.’ There was no more success on the Tuesday either.

Pay was a recurring problem. Contractors were not easily persuaded to offer extras no matter what the circumstances: ‘A man was killed by a fall this morning in the waggon face east end of Nanty Hill. The men in consequence turned out for more wages but they were not any better for it and went to work on the same terms.’

In general, the Mackenzies knew their own men well, and the diaries are full of entries referring to men like ‘old Price’ or ‘old John Henman’, who would come over from England looking for work and be given it straight away. Men appeared who were last seen tipping at ‘the Liverpool tunnel’, and others who came not on their own but now with a son ready to follow on the navvy trail. There might be the occasional critical comment: ‘Some Irish men were very impudent and saucy’, or bad work noted: ‘culverts built by vagabonds the name Casey & Eagin’. Not that Edward was above criticism himself. William noted in his diary for 2 Feb 1842 that the foundations of the bridge at Rosney were in a poor state: ‘Edward was told to use hydraulic mortar, but did not, neglected doing so which is very bad work in such situations and very often we suffer in consequence.’ This event does not appear in Edward’s notes.

William Mackenzie, who took the early contracts for building French railways, together with Thomas Brassey.

On the whole, the brothers got on well together, and with the workforce they had brought with them. They found the French – and the French authorities – a good deal more difficult to cope with. Sometimes the problem was no more than the sort of fracas that could as easily have happened anywhere. A Frenchman hit one of the contracting staff, and when he came to collect his final pay was ‘very insolent’. He was sent packing, after which the mayor and a gendarme turned up, rather too late to be of any use. Far more disturbing was a series of events that began when one of the French gangers, Lamours, responsible for paying the labourers, collected 5300 francs for work done, and then absconded, leaving the men unpaid. The next day they turned up demanding their cash, but ‘We sent them off’. As far as the contractors were concerned, their deal was with the absent Monsieur Lamours and he had been paid: nothing that happened after that was their concern. The third day of the affair, things grew worse. Brassey appeared on site with Joseph Locke, who was not happy with the quality of the masonry work. Brassey then suggested to Edward Mackenzie that he follow them to Bonnivray. Edward recounts,

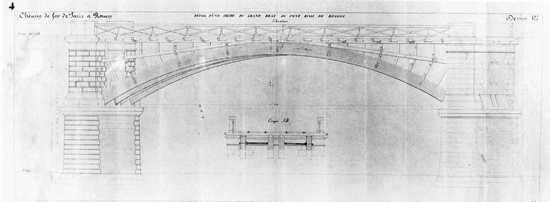

Barentin viaduct, which failed catastrophically and had to be entirely rebuilt.

I followed but was stopped by Lamours men, who said they must be paid before they would let me go. I was kept 2½ hours and was released by some Dragoons sent from Vernon.

The matter was now referred to the authorities, who decided that the Mackenzies had indeed met their legal obligations, but to keep the peace the men would have to be paid. Edward was disgusted: ‘They said this is French law – the people are masters not the magistrates. We had to pay the men 7120 francs – this sum is now to be paid twice.’ He was a good deal more cautious a few weeks later when he had to deal with a somewhat suspicious Belgian ganger, Delmier.

Returned along the line, paid the Belgian and asked his men if they were satisfied he would pay them. They all said they were. I gave him his money and left them.

History was shortly to repeat itself, and in the most embarrassing circumstances. This time not only were Locke and Brassey at the works on a visit, they had the Minister of Public Works with them: ‘Word came through that Delmier men were come to the office. The Belgian had sloped after all the precautions we had taken.’ The result was inevitable: the payment had to be made all over again.

Occasionally the contractors were more fortunate. While working on the Orleans railway, Edward heard that a ganger called Simcox had left without paying his men. There was a fair chance he was heading for home, and sure enough he was caught about to catch a coach to Paris. He was hauled back, made to hand over all the money, 1300 francs, and was then sacked on the spot.

Mackenzie had at least his core of British navvies, and this made life a great deal easier than it was for William Lloyd, who had only started his engineering apprenticeship in 1838 and in 1842 found himself on his way to a post as resident engineer on the ‘Great Northern of France’. It was all very different from the scene he had left behind in Croydon: ‘Then France was French, our bedrooms were not too luxurious, the floors were of red tiles innocent of carpet, water was limited in quantity, and soap was absent from the washstand – this had to be purchased off the chamber-maid.’

He arrived with six navvies to take charge of work at Beaumont, but found there were no men, no tools, no equipment of any kind whatsoever, simply a ‘preremptory order’ to employ 300 men and start work at once. More in hope than expectation, he put up notices asking local peasants to turn up on the next morning with whatever tools they owned. When he went to the meeting place he found ‘a motley crowd of volunteer navvies, numbering more than a hundred, with every species of earth-disturbing implement, and with a perfect collection of wheelbarrows, many of remote antiquity.’ He set this makeshift band to work, but was delighted when a gang of Belgian navvies with experience on the railways appeared looking for work. He hired them on the spot – and created a riot. The French did not want Belgian workers. In fact they claimed they would kill any Belgian who as much as picked up a shovel. Lloyd went to talk to the French, but rather than pacifying them, his speech seemed only to make them more irate. One of the English navvies, known as Tom Breakwater from his having been born on Plymouth breakwater, came up to Lloyd to ask what it was the angry men were shouting. Lloyd explained that they were threatening to throw him in the river, a prospect which Tom Breakwater accepted with equanimity. He coolly remarked, ‘Never mind, master, I’ll pull you out.’ Lloyd had a better scheme. It was, he declared, a King’s Fête day, and everyone could have the day off. This was greeted with great enthusiasm. Lloyd, not surprisingly, felt in need of a restorative and popped in to the local inn, where he was cheerily greeted by the ringleaders of the mini-rebellion. He spent the rest of the day drinking the King’s health with the men who a few hours before had threatened to drown him. What happened on the next day history does not tell. This little adventure at the beginning of his career did nothing to deter Lloyd, who spent much of his life travelling the world as an itinerant railway builder – as indeed did the laconic Tom Breakwater.

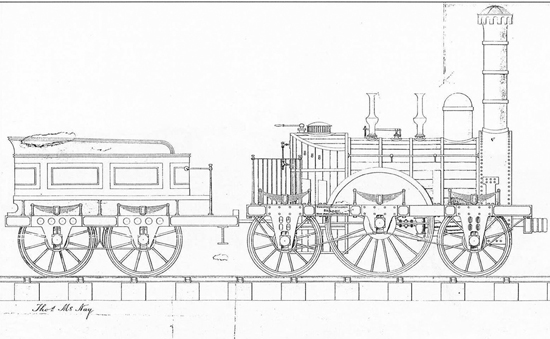

A drawing from William Mackenzie’s office of an arch of a viaduct across the Seine on the Paris to Rouen Railway

Lloyd’s experience was an unusual one. Most French railways appear to have adopted the practice established by Locke and other engineers of leaving the hiring of workmen in the hands of contractors. It was all too easy for a young Englishman, new to the country and not speaking the language, to fall foul of local prejudices. Not that prejudice was limited to French attitudes to the English. Edward Mackenzie, when faced with problems, revealed the typical British reaction to foreigners in his diaries: ‘After breakfast went into the town with Tomes – called about the Stabling by appointment, but as usual with the French no appointment was kept.’ Or again: ‘Paid off Old Blubberhead his store account and took 1000 francs of deductions off his bills and he never made a remark. This is French honesty.’

The world of the railway builders can seem to be a very closed one, into which the larger world of politics never impinged. But no sector of French life escaped the events of 1848, the ‘Year of Revolutions.’ In Paris, the crowds were out on the streets and the barricades were going up. The clamour for reform was turning into a full-scale revolution. To the British in France, events in Paris warranted a diary jotting. What really concerned them was the effect on their workforce, and the problems they faced in getting money from their Parisian bankers to pay wages and bills. The following extracts from Edward Mackenzie’s diary give something of the flavour and problems of the times.

24 Feb Nothing but destruction in the neighbourhood of Paris. Louis Philippe (King) abdicated, all the barriers stopped and the city in open rebellion and Republic proclaimed – less rain afternoon.

26 Feb Arranged for engine and some horses being sent to Dieppe to finish the work there if the present disturbed state of the Country ceased and things became peaceable.

1 Mar Some mechanics from Tours came down in the waggon with me to Boulogne. These men are driven away by the Revolutionaries and not allowed to stop.

9 Mar Some of the bricklayers were standing idle, and said they would go to work no more there, that they were afraid of their lives and that the Frenchmen threw bricks at them last night in the tunnel and told them they must all quit.

I went through the tunnel, all was quiet and no symtoms [sic] of disorder. Two Gendarmes came up and said they had heard something of the row but that they would take steps to prevent it.

The authorities then agreed to do what they could to prevent the intimidation of the British workers. That problem was, however, replaced by a new one.

12 Mar Had word from Laffitte stating that they had stopped payment and that the Bank would be closed for a time, and he said also the 60,000 francs advised as being sent off for us had not been sent.

The money was sent only for it to be immediately misappropriated.

14 March When I got to the office this morning enquired immediately (from a letter just received from Faurin telling me Adams had played me a trick) from James whether the checks I had given him yesterday were cashed. He said no, that Adams had told him the 60,000 francs which had come for us he would take to his own account. Laffite & Co owing him money considered he was first in appropriating our money to pay himself … got a statement of all the facts put on paper connected with this rascally transaction.

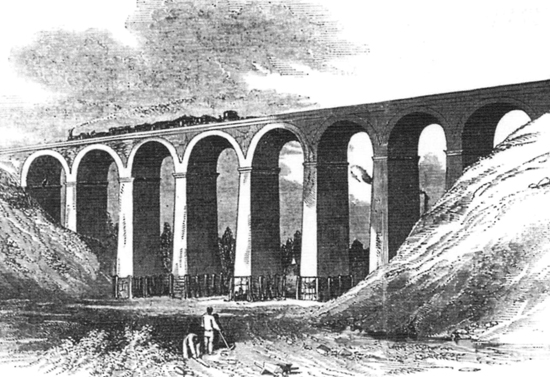

Malaunay viaduct on the route from Rouen to Le Havre, which was strengthened following the collapse of the Barentin viaduct

25 March Paris in a very unsettled and discontented manner, every thief being a King.

His own position was all the time getting steadily worse and he was beginning to pay off the men. Attempts to get more money were constantly frustrated.

19 April We went from here to the Bordeaux railway office, saw Mr du Richmond one of the Directors who said they had no money, and that Government had given notice for all the lines being taken into their own hands.

20 April Told we could not get any more money from the Boulogne Company for construction but that we were to be paid for maintenance 15,000 fr now and the balance the first of May when our upholding would cease.

There was nothing to be done but to ship the wagons and horses back to England and tidy up the business. William Mackenzie drew £400 out of a Liverpool bank to pay the men, and Edward was soon off inspecting a line being built in Belgium. It was to be some time before the Mackenzies were to be back building railways in France.

The financial affairs of the contractor as seen by Edward Mackenzie, preoccupied with the day to day running of a major construction site, were very different from those as seen by the partners, Thomas Brassey and William Mackenzie. William’s diary is full of details of new proposals and political manoeuvring. While Edward bustled around the Paris-Rouen-Le Havre network, William was engaged in finding new contracts, as well as settling problems on existing lines. His reputation had won him contracts in France and other parts of Europe, while at the same time other contractors, in France and Belgium, were trying to buy his favour or gain it via threats of political influence. He had already by this time begun work on the Orleans & Bordeaux Railway, but was working from his London office. A diary entry on a visit in January 1845 serves as a reminder that the big contractors needed to be conversant with more than just civil engineering.

17 January Mr Haddon, Winch, my nephew and I went and called on Mr Wright respecting pattern 1st Class Carriage for Orleans & Bordeaux Railway.

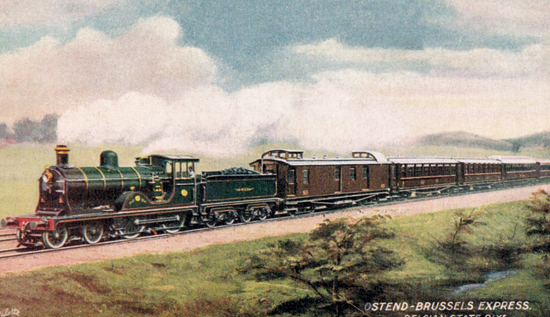

The official opening of the line from Paris to Le Havre included the blessing of the locomotive

A few days later he received a very different proposition.

29 January About mid day the Belgian Gentlemen Contractors called on me to propose that I would consent to amalgamate the Bordeaux Contracts with them and Barbier to which proposal I refused to listen -they strongly advised me to do so as sound Policy or the Council of State upset my Contract – They then told me Barbier has sent for them to join him and they were to find Capital and knowledge and experience, none of which he had – they said hitherto they had not seen him. They asked me if I would allow them an interview tomorrow at 12°ck respecting a Railway in Belgium. I complied.

Mackenzie was aware that although the English were a major force in railway building in Europe, their continental associates had the ear of government, as a later entry shows.

13 March Government in my opinion are more disposed to thwarting as much as possible than be honest. Laurent & Luzarch are listened to in everything. The feeling is French use English money and English have no control whatsoever.

It was a situation rife with wheeler-dealers, bribes and the payment of backhanders. Powerful men like Mackenzie and Brassey were in a strong enough position to stand above such mean dealings. Mackenzie’s diaries record a meeting with one such easer of ways and opener of palms, Mr Cunningham.

1 April He then said have you plenty of money. I replied no – he then wished to impress on my mind he had worked hard for us with his influence on the Havre line and would be glad of a few Hundred pounds for such service. I flatly declined him. He said in Spain he ought to have some smacks. I would not listen to such proposal, his influence is Humbug.

It was all very well for the Mackenzies of the contracting world to take a high-principled attitude, but the lower echelons of contractors and sub-contractors were constantly on the brink of bankruptcy. Very little had to go awry with a contract for a slim profit to turn into a loss. To ensure that contractors could meet their obligations to workforce and suppliers, it was required that they should deposit money with the railway company as a safeguard. Mackenzie noted that one of the first things he did before starting work on the Orleans, Tours and Bordeaux Railway was to deposit £80,000 with the government. Small contractors often sank all their cash into equipment and prevaricated as long as possible over their deposits. Some prevaricated for so long that they were overtaken by events, with drastic consequences. William Mackenzie visited the Orleans area in January 1843, a journey involving ‘the worst roads and worst travelling I ever experienced’, and arrived in Nancy to be confronted with just such a situation, involving a minor contractor.

Rennaud was going to shoot himself. It turned out when he took his contract he did not deposit his caution money (£1200) to the Ponts et Chaussées and moreover he had not the means and in the case the said works would again be adjudicated and if let for more money he would have to make good the difference to Government as far as his means would cover. In this state of mind he would come to any terms with me and he had thus far transferred his interests to us. I had him fast but under the circumstances I behaved liberally to him in giving him & Dubeck half the profits allowing us a sum for Cash and Materials but all cash and management wholly and solely to be in McK & Brassey control whatsoever any Mem” of Agreement that comes O’Neill’s claim which I would not at all admit under the circumstance of public adjudication. He brought us interest and the matter was free to us nevertheless I gave him a verbal promise of £100 not to be considered a claim and that his interest had done us any favour whatsoever. His position is wholly and solely the personal interest he professes to have by Deputies, Ministers &c and that he can put us in a Train by connecting ourselves with Rennaud and Dubeck to procure private Contracts from Government that will yield a return of 30 to 40% profit. We of course furnish all the funds and management and manage funds on the Marne and Rhone Canal is the first large job to be obtained. It is 6000 metres in length about 30 miles from Bordeaux. I beg in fear it will be much the same as the canal and turn out that Government would give it to us without either Dubeck’s interest or Rennaud’s and we could do it for a less figure by not being hampered by these speculators who have nothing to lose and might gain something however I will follow it.

His view of Rennaud was a model of charity compared with his comments on Mr Barry of the Bordeaux Board. He was ‘a base double dealing villain’ and he told him so to his face.

Reading the day-by-day account of contractors at work in France, such events obviously stand out, but more impressive is the picture that slowly builds up of the steady, relentless advance of a railway and the immense resources that were needed in its construction. On one day one reads of buying bricks in Paris for tunnel lining: the two batches he agreed on came to a total of a million bricks, for which half the cash was put up in advance. At the opposite extreme, negotiations with a local farmer for permission to open a quarry on his land came to a happy conclusion when the deal was struck for ‘a case of needles and a pair of English scissors’. William Mackenzie’s time was divided between England and France, making deals running into hundreds of thousands of pounds, but he still found time to make regular visits to the works, where he took a minute interest in everything, even-handedly doling out praise and blame. A period in the summer of 1845 shows something of the variety of this life.

23 June Started a contract with Belgian interests – Bischoff-sheam & Oppenheim. Gave sureties – caution money to Belgian govt. 111775.05 fr.

23 July Looking at the Orleans rly – visited No 3 Ballast pit where a new mechanical excavator was about to be installed. ‘Mr Beary the manager must be sent away, he is good for nothing’.

26 July We found a French Ganger going well. Went to Simcox’s platelayers, he had got over the Viaduct and through cutting into the wood and was going on well. I gave his men each one franc for doing so well. We called on an Irish gentleman … he promised to render our men assistance for lodgings in the village.

His brother Edward’s life was far more routine: daily inspection of the works, estimating work done, dealing with local traders, checking the workshops and puffing to and fro along the completed track on one of the contractor’s locomotives. It was a hard life, regularly involving before breakfast what to many would seem like a full day’s work.

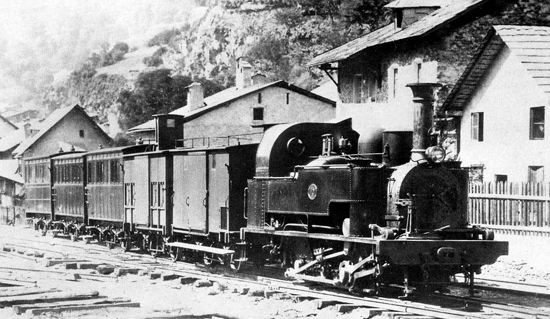

St. Pierre built by Allcard, Buddicom & Cie for the Paris-Rouen Railway in 1845 and now preserved at the Cité du Train, Mulhouse.

As time went on and William became ill – he died in 1851 – Edward took on more and more of the responsibility for the running of the whole concern. The flippant tone of the early diary entries gives way to a new self confidence.

14 July Carriages got off the line yesterday and that the Directors were in a great fright about it I at once went to see them & Baron de Richemont explained the affair to me as being the fault of the points which in my opinion was not the case and 1 told him so.

16 July I met the 9 am train for Poitiers and Charles with me. We left by it taking the letter I have received from the Directors to contradict as much as possible the blame they wished to throw upon us. I got to Poitiers 2 pm and examined all the points &c there as well as every other place along the line and in every instance can show that the blame is in the imperfect state of their rolling stock.

Not everything went smoothly, even for the mightiest of contractors, and Mackenzie and Brassey were confronted by one huge disaster in the collapse of the Barentin viaduct on the Rouen to Le Havre line. It was a massive construction, 100 ft. high and a third of a mile long with twenty-seven arches. In a somewhat self-congratulatory mood William Mackenzie noted in February 1844 that his estimate for the viaduct had been accepted: ‘It was competed for by two French gentlemen against us and we came under them, 10 per cent under the lowest and the next 30 per cent and we in reality are 6 per cent too low – our estimate is 2,008,635 Fr.’ (approximately £800,000). Was the need to cut costs a contributory factor in the events of two years later? Corners were certainly cut, but the contractors claimed it was none of their doing. Perhaps this was so. It is a thought to bear in mind when reading the generally accepted, rather heroic account of their response to the disaster. The story of Barentin is often quoted as an example of Brassey’s stoicism in the face of adversity. Helps, in the biography, at least gives Mackenzie equal billing.

Mr Brassey was very greatly upset by this untoward event; but he and his partner Mr. Mackenzie met the difficulty most manfully. ‘The first thing to do,’ as they said, ‘is to build it up again,’ and this they started most strenuously to do; not waiting, as many would have done, whether justly or unjustly, to settle, by litigation or otherwise, upon whom the responsibility and the expense should fall.

Not a day was lost by them in the extraordinary efforts they had to make to secure millions of new bricks, and to provide hydraulic lime, which had to be brought from a distance. Suffice it to say that, by their indomitable energy and determination promptly to repair the evils and by the skill of their agents, they succeeded in rebuilding this huge structure in less than six months.

The Mackenzie family copy of the book is annotated: ‘This should have been entirely credited to Mr Mackenzie (W). Mr Brassey was not even in France at the time.’ William Mackenzie’s diary shows this to be a case of misplaced family loyalty. It also gives a very firm opinion of where the fault for the catastrophe lay. His entries for 12 January 1846, when he first heard the news, read,

12 January Mr Illidge informed me on Saturday last Barentin Viaduct fell to the ground a heap of ruins – fault – Bad Mortar. We told Mr Locke mortar was bad and proposed to use Hydraulic for mortar and bear half the expense of the extra. He said he would allow nothing, but we were at liberty to use it if we pleased. The result is now to be seen.

13 January Today I met Locke with Mr Brassey. He looked sad and was low in spirit. Afterwards went to Newman’s office where I found him engaged in making a plan for reconstructing Barentin viaduct and instead of building as before hollow piers opening with 4 chimneys 2’ 6” square is now to be solid and the piers instead of brick arches they propose timber ones.

Mackenzie and Brassey went together to inspect the damage: ‘bricks good, mortar infamous’, and then went on to the Malaunay viaduct where they ‘discovered some very ugly cracks in the piers that is a little alarming.’ They had the piers strengthened with the beams. Even so, the French were taking no chances. Before any passenger trains were allowed to use the line, they heaped 3000 tons of earth on the top and left it there for several days. When no cracks appeared, they brought out a goods train of heavily laden wagons and ran that backwards and forwards several times. Only then did they finally declare themselves satisfied.

The Mackenzie-Brassey partnership was one of convenience rather than conviction, and as work came to an end in Normandy they agreed to go their separate ways. The document of October 1850 setting out the details of their separation is fascinating for the light it throws on the huge wealth of the men involved and the extent to which their empires were built in railway share holdings.

Mackenzie took the Orleans to Bordeaux contract and the Pont Audemer iron works, established to provide material for the railways, for which he agreed to pay Brassey £47,000. In return Brassey took on the maintenance contracts for the Paris to Rouen and Rouen, Le Havre and Dieppe Railways for which he paid £4000. There then had to be a division of the spoils: each came away with approximately 3000 shares in French railway companies, mainly the Dieppe line. This reflected the common practice of contractors taking a large proportion of their payment in shares instead of cash. From the general balance sheet, Mackenzie had to pay Brassey £32,053. In all he paid over £80,000 in the final settlement, of which £25,000 was in Great Northern Railway bonds and another £25,000 in North Staffordshire Railway bonds. What emerges is a portrait of rich and powerful men, whose prosperity was almost wholly dependent on the success of the lines they built. Small wonder that they and their counterparts looked as carefully into the profitability of a line as they did into the engineering problems they might have to face.

As work on the first French lines drew to a close, the contractors were busy looking for fresh contracts, and their travels around the continent reinforced their belief that railways were sorely needed. As early as 1845 William Mackenzie had led an expedition to survey proposed lines in Spain. He and his companions set off on 5 April and crossed the Pyrenees in a coach hauled by the unlikely coupling of two bullocks and four mules. By 9 April they reached Castilego. Here they stopped at ‘a very miserable inn’ where to make matters worse the wine was ‘undrinkable’. The next day was certainly no better.

We started from Castilego, the place most miserable with 6 mules and about 4 inches of snow. The stage about 13 miles 3½ Spanish league. We left at 6 o’clock and were 4 hours getting through the pass and ascending we experienced frost and snow. The roads were very heavy. The postilions and beasts could do no more, they executed their whole strength and power – we gave the men some of our real brandy which caused them to scold the mules more and more. They have a custom of talking constantly to them sometimes praising them, other times all sorts of bad names and at times barking like dogs at them.

Adler (the Eagle) one of the first locomotives to run in Germany, was built for the Ludwig Bavarian Railway at the Robert Stephenson works in Newcastle

They eventually reached Madrid, then travelled on to Barcelona, from where they were able to return to France, a good deal more comfortably, by steamer. Brassey was to join with Mackenzie in one last project that grew out of the Spanish expeditions, the Barcelona & Mataro Railway. He was then to continue in a new partnership with Morton Peto and Edward Betts, building railways throughout Europe.

Railway construction in Europe was not quite the simple matter it sometimes seemed of establishing where a line was needed, assessing likely costs and revenue, setting out to raise the money, then either pushing ahead or dropping the scheme. Many lines were promoted due more to the amour propre of local interests than to rational analysis. A great many more were tied to political ambitions. Continental Europe in the early nineteenth century was a patchwork of states large and small, and this pattern was changing all the time. In a world of shifting boundaries and allegiances, railways were seen by many as a unifying force. Among the ambitious politicians who espoused this view was the great advocate of Italian unity, Count Camillo Cavour. He worked assiduously from his base in Piedmont to create a unified Italy. He realized that a nation where citizens of one area could easily move to meet citizens of another had a far greater chance of achieving unity than one where the parts remained in isolation. Railways were to play an essential role in achieving his political dream.

In 1851 Cavour began searching for capital for railway construction, and an obvious first step was to approach one of the most successful railway builders of the age, Thomas Brassey. Negotiations began for establishing a partnership for a line from Turin to Navara; the political element involved a partnership between Cavour’s Piedmontese government, the Italian provinces, Brassey and the local people. Three parts of the structure held, but the fourth, the general public of Italy, showed no interest in joining in. Cavour then turned back to Brassey and suggested that the government should put up half and Brassey and his associates the rest. It probably seems more remarkable in retrospect than it did at the time. Yet here was a nation-state engaging in a major project, aimed both at revolutionizing the transport system of the region and encouraging political unity, applying to a private company in a foreign country for half the funding.

If anything shows just how far Thomas Brassey had travelled since his first contract for the Penkridge viaduct, then surely this was it. For the man himself was not even consulted: the decision was taken on his behalf by a partner in the enterprise – and a junior partner at that – Nathan Giles. And even then, there was more to come. The fact that so successful a contractor as Brassey had unhesitatingly put his own money into the scheme was enough to raise confidence. The Piedmontese, who before were reluctant to invest in the project, now began complaining that there were no shares available. Cavour, who had begged Brassey to take shares in the enterprise, was now placed in the somewhat embarrassing position of asking him to sell them again. Brassey agreed, though it proved a loss on his part, for once the line was open handsome dividends of 14 per cent were declared. The Piedmontese, who had been reluctant to risk a penny, were happily reaping high dividends. On the other hand, Brassey had struck a sound bargain, for he was to be very much favoured when other lucrative contracts were being handed out.

Brassey’s partner, Nathan Giles, was heavily engaged in the arrangements for building the Lukmanier railway, from Lucarno on Lake Maggiore to join the Union-Suisse Railway at Coire. This was another line actively promoted by Cavour. He approached Brassey who in turn handed the planning back to Giles. His description of the negotiations (quoted in Helps’ biography of Brassey) gives at least a hint of the problems faced by anyone attempting to build railways across the complex chequer-board of European states. It begins with Giles’ first meeting with Cavour.

I may mention that it was not unusual for Count Cavour to see people in the summer-time at five o’clock in the morning. My appointment was at six o’clock. I waited upon him as appointed. We then discussed the Lukmanier, and we came to an arrangement. I said, ‘There are no “surveys” in this matter, or no reliable surveys – they are all made by the people in the country. Will you share part of the expense of a definitive survey?’ He replied, ‘I do not think, in the present position of matters, it can be done. It is in Switzerland; and the Swiss are so touchy about any interference of a foreign Government, that I think our doing so would have a prejudicial rather than a beneficial effect; but I should be glad if Mr. Brassey can see his way to making them without any assistance from us.’ I spoke to Mr. Brassey about it, and the surveys were made in the spring of 1858.

The proposal went forward and Brassey agreed to take Cavour over the proposed line, but as inevitably happened from time to time in the busy contractor’s life, other circumstances and other lines got in the way – on this occasion it was a line to Cherbourg and the need to be there for the official opening by the Emperor. Cavour was sufficient of a realist to know that mere Counts must give precedence to Emperors. Giles’ account of his conversation with Cavour is as eloquent a testimony to the reputation of the English contractor as one can imagine, and goes some way towards explaining why his services were so much in demand. Cavour said,

I very much regret Mr. Brassey is not here, as I have looked forward to the pleasure of going over the line with him, and thoroughly understanding how he proposes to construct the two sections, and the carriage road over the mountain. I am already acquainted, through M. Sommeiller, that Mr. Brassey thinks it better to make a good tunnel even in fifteen years than a bad one in six years. I think so too; indeed, I shall be disposed to accept whatever Mr. Brassey proposes, as I have full confidence in his opinion. I should like very much to go over the line with him; and if you will inform me when he will be at Coire, I will do my best to return, and accompany him over the line, as I am most anxious to have my lesson from the most experienced contractor in Europe, and so be able to discuss the question au fond, and with a full knowledge of the facts.

Brassey was more than just a brilliant organizer, who had built up an organization big enough to tackle the most complex problems, he was also a man who recognized abilities in others and encouraged innovation. As part of the growing network of lines out of Piedmont, a route was proposed into France along the pass of Mont Cenis down the Arc valley to Culoz on the French frontier. It was named the Victor Emmanuel Railway, in honour of the King of Sardinia and presented immense difficulties to its builders. Brassey, Jackson and Henfrey undertook the united survey. That was difficult enough in the rugged mountain terrain, but it came up with the daunting result that a tunnel would have to be forced through the solid rock of Mont Cenis, and it would need to be almost eight miles long. Moreover, the tunnelling techniques then in use on English railways would be of no use here. In Britain it was the usual practice on a long tunnel to sink a number of shafts down from the surface to tunnel level, and then work outward from the foot of each shaft. The headings would then link up to create one continuous bore. Such a method was wholly impractical in the mountains, where the tunnel was to run deep under a lofty Alpine peak – at its greatest depth it lay nearly a mile beneath the summit of Mont Frejus. The only answer was to start at each end and work inwards. This required a very accurate survey to establish the alignment. In all, twenty-four survey points were established by the surveyors as they scrambled around the crags, and the results translated into lines of posts set out by the two entrances. During tunnelling, which commenced from both ends, a constant check was kept by sighting back down the excavations with a telescope. It is very doubtful, even then, if the tunnel could ever have been completed without the invention of a new type of boring machine by Brassey’s agent, Thomas Bartlett, who was put in charge of the construction. He invented a pneumatic drill, which hammered away at the rock at the rate of 300 strokes per minute. The compressors were water-powered, and the compressed air produced was used to ventilate the galleries as they were advanced deep into the mountain. Progress was not spectacular: the tunnel was only pushed forward at a rate of half a mile a year, but given the technology available (for instance the fact that nothing more powerful than common black powder was available for blasting), this was in itself a triumph.

The directors of the Barcelona to Mataró pose with the first locomotive Mataró.

At first the tunnel was advanced as a gallery approximately 10 feet square, which was gradually extended to a 26-feet-wide tunnel, with an arched roof rising to a height of 25 feet and brick-lined throughout its length. As the tunnellers dug deeper into the mountain, compressed air alone was no longer enough for ventilation, so a technique was used that would have been familiar to medieval miners. The tunnel was divided by a horizontal brattice, so that air could be drawn into the lower half of the workings and continue on its way out along the upper section. Work was inevitably slow in the early days, as engineers and workmen alike struggled to overcome new problems with new technology. The pace gradually accelerated and the two ends met with commendable exactness on Christmas Day 1870. As a mark of his appreciation of the work put in by Bartlett on the pneumatic drill, Brassey awarded him a bonus of £5000.

It is not possible to give details of all the works undertaken in Europe by Brassey and his associates, but a table at the end of this book (see Appendix) lists his overseas contracts, together with the length of track involved and the partners with whom he co-operated. It shows a grand total of 6598 miles of track laid in Europe, America, Asia and Australia, of which almost 2000 miles were constructed in continental Europe.

Brassey had to be more than a mere contractor, a man brought in when the engineers and promoters had decided what was to be done. He had to be a diplomat, able to speak as an equal to politicians, aristocrats and, when needs be, emperors. Happily he was helped by his own disposition. He was sure of his own abilities, and liked to be judged by his own results; as a consequence he was inclined to judge others by the same standard rather than by whatever titles they might happen to have tagged on to their names. There is a well-known anecdote about Brassey and the honours he received:

Returning from Vienna, Mr. Brassey was waited upon at Meurice’s Hotel, Paris, by one of his agents, who arrived in the room at the very moment his travelling servant Isidore was arranging in a little box the Cross of the Iron Crown, which Mr. Brassey had just before received from the Emperor of Austria. Made acquainted with the circumstance, the agent complimented his chief as to the well-merited recognition of his services, &c, and the conversation continued on Foreign Orders generally. Mr. Brassey remarked that, as an Englishman, he did not know what good Crosses were to him; but that he could well imagine how eagerly they were sought after by the subjects of those Governments which gave away Orders in reward for civil services rendered to the State, &c. He added, that in regard to the Cross of the Iron Crown, it had been graciously offered to him by the Emperor of Austria, and there was no alternative but to accept this mark of the Sovereign’s appreciation of the part he had taken in the construction of public works, however unworthy he was of such a distinction. ‘Have I not other Crosses?’ said Mr. Brassey. ‘Yes,’ said his agent; ‘I know of two others, the Legion of Honour of France, and the Chevaliership of Italy. Where are they?’ But as this question could not be answered, it was settled that two duplicate crosses should be procured at once (the originals having been mislaid) in order that Mr. Brassey might take them across to Lowndes Square the same evening. ‘Mrs. Brassey will be glad to possess all these Crosses.’

He needed to have a cool head and be sure of his own ground when threading the labyrinthine ways of European politics. The negotiations over the Moldavian railway system make up a story in which the patience of Job would have been put to the test. A proposal was put to Brassey in 1858 by Adolphe de Herz of Frankfurt for a line to join the Carl-Ludwig Railway in Austria to Czernowitz on the border and hence through Moldavia to Galatz on the Danube. It was a major undertaking, a 500-mile-long route with an estimated cost of £65 million – an estimate which was highly approximate since no one had yet looked at the ground let alone surveyed it. But engineering problems were as nothing compared with political problems. Piedmont was building up an armed force and Austria was matching the movement, each inevitably claiming, in tones of shocked innocence, that they were only doing so as protection from the other. Soon France, Sardinia and the Papal States were involved and talks gave way to the harsh realities of the battlefield. Railways had to be forgotten until peace finally settled over Europe in 1861. The political situation, however, was still far from clear, so it was decided to forget about the Austrian part of the route for the time being and concentrate on the 300-mile route through Moldavia.

In September 1861, McClean of the engineering partnership, McClean and Stileman, set off to make a survey and reported back in November with a recommendation that the works should be let to Brassey, Peto and Betts for £2,880,000. Guarantees were offered, but as they were dependent on the whole work being completed within five years nothing came of it. A proposal by Brassey and Glyn the bankers that the line be divided up and each section financed separately was turned down. Prince Leo Sapieka, chairman of the Carl-Ludwig railway, asked Brassey for advice. The reply was neat, precise and to the point.

Prince, After full consideration of the Moldavian Railway project, it seems that we are both of opinion that there is a serious defect in it; namely, that it has no junction with your Carl-Ludwig Railway at Lemberg; and I fear you will have considerable difficulty in obtaining the support of the public to an isolated scheme for the Principality of Moldavia.

A working replica of Mataró

If a company could be formed for the entire line from Lemberg to Galatz, with the branches to Jassy and Okna, it would, I think, be favourably received; and I venture to suggest that your Highness endeavour to form a combination with Baron Anselm Rothschild and your friends at Vienna for carrying it out.

You will easily be able to form an approximate idea of the capital required; and should my co-operation as contractor be thought desirable, you may consider I will accept one-third of the contract price which may be agreed upon in shares of the company.

Rothschild, however, was to show no interest and another year ticked by. McClean and Stileman made another detailed survey in 1863, and now the government came up with a new concession at better terms, with a guaranteed interest payment and the government to put up a quarter of the capital. Things were beginning to look more hopeful when another contender appeared, the Spanish banker Marquis Salamanca, who offered to build the whole line without the government paying their quarter share – an offer which, not surprisingly, the government found irresistible. The principality now felt they were in the ideal bargaining position – with the promise of Spanish money and an alternative contractor they would acquire Brassey expertise on far better terms. Unfortunately for their calculations, the British refused to comply, announcing they were all going home and the Moldavians could get on with it. This was far from the amalgamation of Brassey and Salamanca that the Moldavian government had hoped for. Brassey, in his usual blunt manner, told Salamanca that if he would put £500,000 into the scheme, then he, Brassey, would match it. But the Spanish banker was unable to come up with the funds, and another plan collapsed. At this point De Hertz, several years and one war later, reappeared on the scene and was encouraged to approach Brassey yet again. Agreement was finally reached in 1868, ten years after negotiations had first started. Brassey, Peto and Betts had then offered to construct the railway at a rate of £9,600 per mile: now Brassey was being offered the same work at nearly double the price. Even so, he was not offered the whole route, but only 360 out of the original 500 miles. By 1870 Brassey had completed everything for which he was contracted: none of the rest was open. The politicking had produced ten years of delays, a doubling of costs and a result in which the one effective contractor had finished his part of the works, while others who had inveigled their way into the business had achieved nothing.

The engineer Charles Vignoles had many difficulties making this section of the line beside the River Ebro on the line from Santander to Bilbao

Political machinations were not the only problems that Brassey had to face in his middle-European railway days. The Lemberg and Czernowitz section of this long cross-European route was to cause him great problems; once again these were political, not engineering problems. Whilst building the line he had to pay his workforce; furthermore having bought up bonds to help finance the building, he had to pay interest on them until the line was completed and the government-guaranteed interest came into force. He held a huge stock of shares, but he needed to see a line open before he could cash in on them; until that point was reached they were so much waste paper. It was a situation where it was absolutely imperative that the line was completed as quickly as possible, and such minor difficulties as a war between Austria and Prussia simply had to be overcome.

In 1866, Victor Ofenheim, Brassey’s agent in Austria, was faced with a dilemma. The navvies were toiling away at Lemberg, but the money to pay them was 500 miles away in Vienna, and in between them were the Austrian and Prussian armies, lined up on either side of the track. Ofenheim successfully carried the money as far as the edge of the war zone at Cracow. There he was told that there were no engines of any sort available. He nonetheless found an ageing relic in a shed. All he needed now was a driver. There was an understandable reluctance among engine drivers for this task, but Ofenheim succeeded by offering a huge fee for the dash and promising the driver that if he did chance to get killed, his family would be looked after for the rest of their lives. So off they set, regulator wide open, dashing between the enemy camps so fast that by the time the sentries had registered the fact that there was a train on the line, it was out of reach. The navvies were paid; if they had not had their money they would have simply gone home. Instead they worked on, and the line was opened.

The difficulty involved in getting money to the men in Austria was something of a one-off problem: contractors were not often required to build their lines through war zones. On the Bilbao to Tudela line (described in more detail below), it was a perpetual problem. Although there was no actual war in progress to impede construction, the country was riven by dynastic quarrels. Queen Isabella was still in her teens, and the effective ruler was her mother, Maria Cristina. They were opposed by a very powerful Carlist faction, supporting the heirs of Charles II who were in control of many areas of public life. Brassey was not the only British railway builder who must have cursed the day he ever signed a contract in Spain. The Bilbao to Tudela railway was to cost far more than it was ever to deliver. For a start there was the problem of paying for the work in a country where paper money was almost unknown, and the rest was, to say the least, a trifle suspect. The secretary to the company gave a graphic account of what this meant in practice:

The Bank was not in the habit of having large cheques drawn upon it to pay money; for nearly all the merchants kept their cash in safes in their offices, and it was a very debased kind of money, coins composed of half copper and half silver, and very much defaced. You had to take a good many of them on faith. 1 had to send down fifteen days before the pay day came round, to commence getting the money from the Bank, obtaining perhaps 2,0001. or 3,0001. a day. It was brought to the office, recounted and put into my safe. In that way I accumulated a ton or a ton and a half of money, every month during our busy season. When pay week came, I used to send a carriage or a large coach, drawn by four or six mules, with a couple of civil guards, one on each side, together with one of the clerks from the office, a man to drive, and another a sort of stable man, who went to help them out of their difficulty in case the mules gave any trouble up the hilly country. It was quite an operation to get this money out. I was at the office at six o’clock, and I was always in a state of anxiety until I knew that the money had arrived safely at the end of the journey. More than once the conveyance broke down in the mountains. On one occasion the axle of our carriage broke in half from the weight of the money, and I had to send off two omnibuses to relieve them.

Gradually the locals were persuaded to accept paper money, but that was only one part of the problem solved. One of the sub-contractors on the line was a leader of a Carlist faction with immense local power. The local agent, Mr Tapp, went through the usual procedures of railway work. A contract had been agreed, and on the due date the completed work was measured and the sub-contractor would then be paid what he was due. In the case of a dispute, the matter was to be put to an independent arbitrator. This was not the Carlist way:

He had over 100 men to pay, and Mr. Small offered him the money that was coming to him, according to the measurement, but he would not have it, nor would he let the agent pay the men. He said he would have the money he demanded; and he brought all his men into the town of Orduna, and the men regularly bivouacked round Mr. Small’s Office: – they slept in the streets, and stayed there all night, and would not let Mr. Small come out of the Office till he had paid them the money. He attempted to get on his horse to go out – his horses were kept in the house (that is the practice in the houses of Spain); but when he rode out, they pulled him off his horse and pushed him back, and said that he should not go until he had paid them the money. He passed the night in terror, with loaded pistols and guns, expecting that he and his family would be massacred every minute, but he contrived eventually to send his staff-holder to Bilbao on horseback. The man galloped all the way to Bilbao, a distance of twenty-five miles, and went to Mr. Bartlett in the middle of the night, and told him what had happened. Mr. Bartlett immediately got up and went to the military Governor of the town, who immediately sent a detachment up to the place to disperse the men. This Carlist threatened that if Mr. Small did not pay the money, he would kill every person in the house. When he was asked, ‘Would you kill a man for that?’, he replied, ‘Yes, like a fly,’ and this coming from such a man who, as I was told, had already killed fourteen men with his own hand, was rather alarming.

Sharp Stewart 0-6-0T locomotive at work at a colliery in Spain

An early British locomotive, the 1869 Dubs at a sulphur and copper mine in Spain

When Brassey joined William Locke, Joseph Locke’s nephew, on the building of the Barcelona to Mataro line, they had more trouble with the Carlists. This time the latter demanded £1200 from the railway company for their funds, in what can best be described as a form of political protection racket. William ignored their threats, and a week later a bridge was burned down. When that produced no result, a band of around 200 partisans stopped a contractor’s train, hoping to discover Locke on board, but when he was not found they settled for ransacking the train instead. Having failed to kidnap Locke, they captured instead a guard, Alexander Flancourt. This time there was no option but to call in the military, who soon tracked the partisans down and the guard escaped in the confusion of the fight. Life for railway builders in Spain was not dull.

A feature of works such as this is that whereas in the early days contractors such as Brassey relied mainly on their own navvy gangs, by the 1860s they were employing local labour. It was obviously a sensible course in many ways, though the hard-won reputation of the British navvy ensured that he kept his title ‘Prince of Workers’ against all comers. Brassey, who had more opportunities than most to gauge the value of workers from different countries, was able to compare their various qualities. The Italians were perhaps the most idiosyncratic. The Piedmontese came in for fulsome praise. One of Brassey’s agents wrote, ‘For cutting rock, the right man is a Piedmontese. He will do the work cheaper than an English miner. He is hardy, vigorous, and a stout mountaineer; he lives well, and his muscular development is good’ – and he was appreciated as a steady, sober workman. At the opposite end of the scale came the Neapolitans. They would arrive as an entire clan with their ‘chieftains’. Perhaps a thousand men and boys would turn up in one group. They built their own settlements of rough huts made of mud and branches and here the old men stayed to look after the cooking, while the rest went to the diggings. Women were left behind in the villages. Nothing would persuade the Neapolitans to take on the heaviest work. They did what they had to do, lived frugally, and after six months’ work packed up their pots and pans, gathered their savings together, and headed for home.

The Germans had less endurance than the French, and the Belgians were generally regarded as better than both. The Scandinavians, perhaps unexpectedly, did not share characteristics. Danes, declared Rowan, the agent for Peto, Brassey and Betts, were very steady workers and the sub-contractors were a ‘very superior class of men’. Danish labourers worked in their own way, at their own rate: they started work at 4 o’clock in the morning during the summer and plodded on, not at any great rate, until 8 o’clock at night. During that time they knocked off for five breaks at least, each of which lasted half an hour. The Swedes were ‘troublesome’, or, to put it bluntly, they drank.

The contractors were also in a good position to assess the quality of the engineers, and the Englishman, reared in the learn-as-you-go school of practical experience, took a dim view of the theorizing Continentals.

The great fault of Danish technical education is the overdoing of it. The young men are kept in school till they are twenty-five. They come out highly educated; utterly ignorant of the world, but educated to a tremendous height …

They have been in the habit of applying to one of their masters for everything, finding out nothing for themselves; and the consequence is, that they are children, and they cannot form a judgment. It is the same in the North of Germany; the great difficulty is, that you cannot get them to come to a decision. They want always to enquire and to investigate, and they never come to a result.

It was generally agreed that if the British navvy was the king of workers, then, in the early days at least, the British engineer was also internationally acknowledged as king of his profession. Even on lines where it might have been thought that national pride would have dictated the choice, the British were often still preferred. Cherbourg, facing across the Channel towards the old enemy, Britain, was in the 1850s being fortified as a naval base. A railway company was set up to build a strategically important line through to Nantes, and the president was to be the resoundingly entitled Count Chasseloup Laubet. The engineering work, however, went to Joseph Locke. It was not to be a happy line for Locke in one sense. Scaffolding collapsed under him while he was inspecting tunnel workings, leaving him with a fractured knee and a permanent limp. Perhaps he received some consolation from the grandeur of the royal opening, attended by Louis Napoleon and his Empress and by Queen Victoria.

The great engineers were themselves treated like royalty, albeit minor royalty. Belgium was in some ways like Britain: a small country with important mineral resources, a rapidly developing industrial base and the need to link mines, industries and seaports together. When Leopold I came to the throne in 1831, he proved to be an enthusiastic promoter of railways, and had the foresight to see that there was more sense in planning and building the basic network as a rational whole rather than letting it come together in piecemeal fashion. Given the inter-company rivalries, not to mention the gauge wars, that were to plague Britain, his arguments were irrefutable. Leopold turned to the men of the day, George and Robert Stephenson. Robert was to supply Belgium with their first locomotive from his Newcastle works in 1834, and the following year they both went to meet the King to discuss his grand schemes. George Stephenson, his early set-backs on the Liverpool & Manchester now behind him, clearly enjoyed the feting and the compliments. He wrote home in high good spirits: ‘King Leopold stated he was very glad to have the honour of my acquaintance. He seemed quite delighted with what had taken place in Belgium about the railways.’ To the Belgian people he was a hero, invited to every important official opening and even made a Knight of the Order of Leopold, an honour which was surely never envisaged by the ten-year-old lad who went to work at the local colliery. Robert was to receive the same honour.

A train at St. Cenis: the line was originally worked over the Pass, using the Fell system, with a third rail

George Stephenson’s work in Europe was to be limited by ill-health. In 1845 he followed Mackenzie on the difficult journey over the Pyrenees and developed pleurisy. He struggled back to England, and his doctor took 20 ounces of blood from him during the crossing, which he said, not surprisingly, left him ‘very weak’. After that he returned to his home, Tapton House, near Chesterfield, where he concentrated on the intriguing problem of trying to grow straight cucumbers. Robert continued to work, and the Newcastle factory was kept busy providing locomotives for railways throughout Europe. The roll-call of railways supplied with Stephenson engines even as early as 1840 is an impressive one: three lines in France, the state railways of Belgium, Austria, Italy and Russia, and a whole clutch of lines in Germany. Inevitably, countries would soon be building their own locomotives: engines designed for British terrain were by no means always as well suited for topography as varied as the Alps or the great plains of Central Europe, but in the 1840s Stephenson & Co. could proudly claim to be the world’s leading manufacturer.

The route over the St. Cenis Pass was eventually replaced by this tunnel.