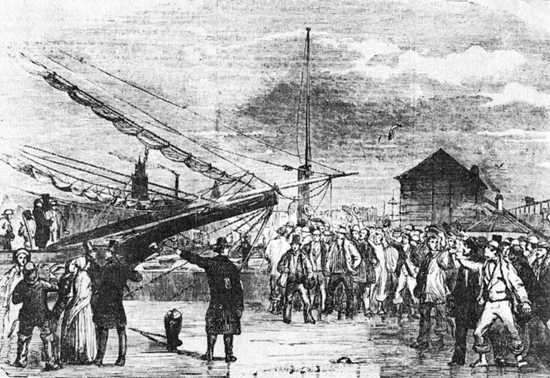

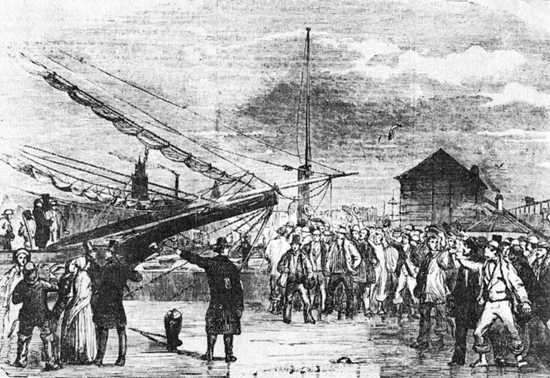

Navvies embarking for the Crimea at Birkenhead in 1854

It is all too easy to see railway construction as existing in a vacuum, insulated from the turmoil of politics. True, events such as the revolution of 1848 had a major impact on railway construction in Europe, but it was an indirect effect. British engineers and contractors responded to these immense upheavals in the political structure of the continent much as they might to a strike for better pay: they were unwelcome intrusions affecting the smooth workings of their enterprise. The rights and wrongs of the situation were simply not their concern; all they wanted was for difficulties to be resolved so that the really important matter of sending rails snaking across the continent could continue. The Crimea offered something very different: here it was not a case of politics getting in the way of progress, but of the politics determining events. Indeed, it was international politics that sent British navvies to the heart of a war that began as a conflict between Russia and Turkey.

A great deal of the trade between Europe and the Indies still went overland, using the old caravan routes through Turkey and Asia Minor. Turkey in the early nineteenth century was part of the decaying Ottoman empire, which was under threat from the steadily growing might of Russia. Whoever controlled the Black Sea controlled the land route, and the Russians were on the lookout for any excuse to wrest that control from the Turks. The ostensible arguments that precipitated war between Russia and Turkey involved such arcane factors as the ownership of the keys to unlock the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Bethlehem. In reality, the quarrel was over who should control the territory that had belonged to the enfeebled Ottoman empire. In November 1853, the Russian fleet sailed out of Sevastopol to attack the Turks. It was not so much a battle as a massacre in which the Turkish fleet was annihilated and some 3000 Turkish sailors were killed. There was a flood-tide of horror and revulsion in England and France, although the cynical might declare it was generated more by political than humanitarian interests. The two governments were determined to prevent Russian expansion to the west and were quite prepared to manipulate public opinion to achieve their ends. They were wholly successful. When in March 1854 Britain and France declared war on Russia, very few asked why war was necessary or what the objective was.

Britain had been at peace since the end of the Napoleonic wars, and in the intervening years the nature of the army had changed. No one expected to fight a war in Europe, so it had been given over to ceremonial and display. Regiments vied with each other like birds of paradise to see which could put on the most exotic and colourful display. The ordinary soldiers, poorly paid and badly fed, were no more than mannequins, displaying ever more gorgeous uniforms in ever more immaculate displays. The slightest falling away of standards – a dirty button, a foot placed out of sequence – was greeted with the vicious punishment of the lash. This was the army of popinjays and paupers that was sent to the distant Crimea to fight a real war in which blood would be spilled.

Navvies embarking for the Crimea at Birkenhead in 1854

There were early successes as the Anglo-French forces advanced into the Crimean peninsula having defeated the Russians at the battle of the Alma, but they failed to follow up this advantage. In the event the war settled down to a long siege of the Russian fortress of Sevastopol. Nowhere was the deficiency of the British high command more cruelly revealed. Here was an army, ill equipped and ill prepared, camped out on an inhospitable, muddy plain with impossibly long lines of communication. The army had arrived in September, just in time for the freezing winds that would make life a misery and the driving rain and snow that would turn the whole of the surrounding countryside into an all but impassable quagmire. The British army was no longer fighting the Russians: it was fighting cold, starvation and disease. Ships could deliver supplies to the ports, but there was no way of getting them to the besieging army, other than on the aching, bent backs of the men and a few pitiful ponies.

By the autumn of 1854, some 30,000 British soldiers were camped out on the ridge above Sevastopol, their only communication with the outside world just one dirt track which was daily becoming less usable. Henry Clifford, one of the officers at Balaclava, described the conditions in his letters home.

Our next affliction is want of transport for the Army. It is too bad that Government has made no provision in this department. We have, till lately, been entirely dependent upon the Russian ox wagons captured when first we landed and a few Turkish ponies with pack saddles to bring our rations and forage for horses from Balaclava, a distance of about four or five miles. But the cold, want of food, and hard work have killed the oxen and ponies, and the roads are impassable. We now only get a quarter of half rations of pork and biscuit, which is brought up by the few remaining ponies, and we are obliged to send our Chargers to Balaclava for their forage.

A sorry state of affairs for a cavalry officer, but by the December things were even worse.

The roads have been so bad between the Camp and Balaclava we have had great difficulty in providing our siege guns with ammunition, our artillery horses dying three and four a night.

Military opinion was being influenced, as conscientious soldiers such as Sir John Burgoyne spelled out the problems. He wrote to Lord Raglan,

To save conveyance of forage, all the cavalry and a large proportion of artillery horses are moved down to Balaklava; still, it is with difficulty that the troops can be kept supplied even with provisions. There is a lamentable deficiency of fuel for cookery, and materials for some kind of shelter better than tents are of primary necessity – all, too, before we can attend to getting up heavy guns, shot and shells. You may conceive the state of our men, and how hard are the duties, from the following: Two soldiers (a double sentry) on lookout in our more advanced trench in front of our batteries, were surprised two nights ago fast asleep at their posts by a small party of Russians, and bayoneted! a most brutal act. This serious crime, compromising the safety of perhaps thousands, and so derogatory to every military principle, was justified, excused, by the officers on the plea that human nature cannot support the fatigues that the soldiers have to undergo. The reports from commanding officers of regiments and generals are to the same effect. The army is sickly to a grievous extent, and is declining numerically as well as physically.

Had this war been fought in the eighteenth century, then the above would have constituted no more than an internal army debate, but there were outside observers in the Crimea. William Howard Russell of The Times sent back his reports which were read by the public at large. He was brief, blunt and angry.

There is nothing to eat, nothing to drink, no roads, no commisariat, no medicine, no clothes, no arrangement; the only thing in abundance is cholera.

The generals may have been powerless, but the cries of misery were not entirely unheard. Morton Peto was by then a Member of Parliament, and he suggested to Palmerston that a railway could be built to link camp and harbour. The idea was eagerly seized upon and on 2 December the Duke of Newcastle wrote to Raglan that Peto and Betts ‘have in the handsomest manner undertaken the important work with no other condition than that they shall reap no pecuniary advantage from it.’ Peto called on his old associate Brassey who helped organize the whole operation, and between them they wheedled, cajoled and bullied railway companies all over Britain into giving them supplies and equipment. Now all that was needed was the manpower. Peto, Brassey and Betts were absolutely insistent that this was to be a civilian navvy force, answerable solely to the contractors and not subject in any way whatsoever to military discipline.

The organization on the ground went to Peto’s chief agent, Beattie, who was the first to arrive in the Crimea with his engineering staff to prepare the way. Colonel Gordon wrote enthusiastically from the camp,

The civil engineers of the railway have arrived, and we hope soon to see the navvies and the plant. No relief that could be named will be equal to the relief afforded by a railway. Without the railroad I do not see how we can bring up guns and ammunition in sufficient quantities to silence the guns of the enemy.

Back in England Peto and Brassey’s faith in their navvies was being more than justified, as the office in London’s Waterloo Road was besieged by volunteers; men who had worked in vile conditions around the world and saw no reason to believe the Crimea could offer anything worse. Some were moved by patriotism, others were attracted by the good rate of pay – from 5 shillings to 8 shillings a day – and a six months’ contract. In popular mythology, the navvy was a rough, tough, boozy, brawling, immoral threat to decent society. Suddenly, he was a hero. The Illustrated London News wrote,

The men employed in our engineering works have been long known as the very elite of England, as to physical power; broad, muscular, massive fellows, who are scarcely to be matched in Europe. Animated, too, by as ardent a British spirit as beats under any uniform, if ever these men come to hand-to-hand fighting with the enemy, they will fell them like ninepins. Disciplined and enough of them, they could walk from end to end of the continent.

The navvies, who seldom got a good press when constructing railways at home, were seen as heroes when they left for the Crimea: shown here laying in to Russian troops.

The navvies were, in reality, neither as wicked as the myths suggested nor as heroic as the popular press would have wished. They were hard men with a hard life, but their preoccupations were no different from those of other workers. There was a delay in the departure of the train taking the men from London to Liverpool, as the navvies queued to sign a paper allowing the contractors to make regular payments to their families while they were away. The first detachment consisted of 500 men: 300 navvies, 100 carpenters, 30 masons, 30 blacksmiths, 12 engine drivers and men from assorted specialist trades. Along with them went three doctors and three scripture readers. The care taken of these workmen was in marked contrast to the conditions imposed on the hapless British soldiers, the first batch of whom, maimed by injury and wracked by illness, was now returning to Britain. Each navvy was fully equipped, and the list of his supplies would have astonished the average soldier. He was given:

1 painted bag

1 painted suit

3 coloured cotton shirts

1 flannel shirt (red)

1 flannel shirt (white)

1 flannel belt

1 pr. moleskin trousers

1 moleskin vest lined with serge

1 fear nought slop [a heavy woollen jacket]

1 pr. long water-proof boots

1 pr. fisherman’s boots

1 pr. linsey drawers

1 blue cravat

1 blue worsted cravat

1 pr. leggings

1 pr. boots

1 strap and buckle

1 bed and pillow

1 pr. mittens

1 rug and blanket

1 pr. of blankets

1 woollen coat

1 pr. grey stockings

2 lb. tobacco

The Duke of Newcastle went to see the first embarkation and asked Peto what a collection of tarpaulins was for, and was told that they were for use by the men until wooden huts could be completed. ‘What a good thing it would be if some could be sent out for our poor soldiers, who have to sleep on the bare ground!’ said the Duke. Peto told him he could get as many as he wanted in two or three days. The Ordnance Department who had completely failed to provide anything in the way of decent accommodation, expressed outraged horror at such ‘irregular’ proceedings and Peto’s offer was refused.

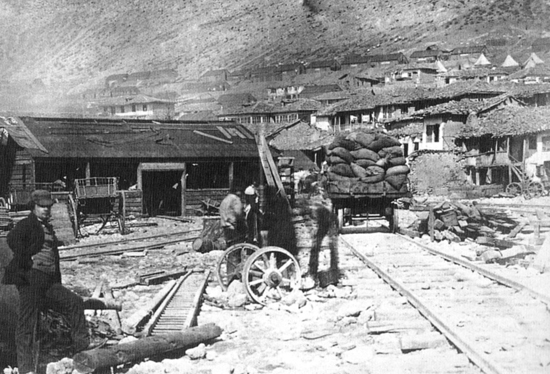

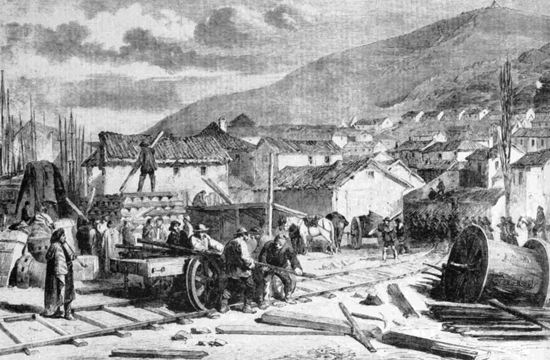

The ships set off, laden with rails, sleepers and stores. It was originally intended to work the line using horses and stationary engines, but locomotives were later to be added to the cargoes leaving England. The ships were held up for days by severe storms in the Bay of Biscay, but the navvies were not going to let a little matter like seasickness affect their way of life. On the stopovers at Gibraltar and Malta they got splendidly, riotously drunk and consequently arrived in the Crimea in fine form. Views of the navvies and the railway they were to build were mixed. Sir John Burgoyne wrote of them as ‘fine, manly fellows’, but Captain Clifford was a good deal less impressed. In his diary for 8 February 1855 he wrote, ‘The Navvies look “unutterable things” at Balaclava, but have set to work at “The Railway” more because it is their nature to do so than anything else. For my part, I wish they would make us a good road, for I have little faith in the proposed Railway.’ It took him less than a week to change his mind. On 11 Feb 1855 he wrote, ‘I was astonished to see the progress of the Railway in Balaclava on Friday. The navvies in spite of the absence of beefsteaks and “Barkeley & Perkins Entire” work famously, and as I have before mentioned do more work in a day than a Regiment of English Soldiers do in a week.’

Progress was indeed phenomenal. Beattie had been instructed to push ahead as fast as possible, and not to be too particular about the standards of construction – the railway would not, everyone hoped, have to last for very long. As early as 11 February, Sir John Burgoyne was able to write,

I am happy to say the railway works are progressing. They have a line of rails from the centre of the town to a little way out; from about half a mile farther they will have a very steep incline, and a stationary engine, and, when workable to the top of the heights, will be of vast service.

The one voice not raised in praise of the builders of the Crimean Railway was that of Russell of The Times. Many of the men were living in hulks in the harbour and Russell described a fight that broke out and almost became a full-blown riot. What they need, he declared, is a sharp lesson from the Provost Marshal – but that would not happen. The contracts specifically excluded the navvies from martial law. But though he grumbled about the men, he could not deny the speed and efficiency with which they worked. He went off one day to view a part of the besieging forces, to return a day later to find his quarters unrecognizable; where once there had been a walled courtyard, there was now a railway track. And before he had got over that surprise, the whole house was shaken as a somewhat inaccurate lumberjack felled a tree, which landed on the roof and carried away one whole balcony. Perhaps one of the navvies had read his report.

Within ten days of the first landing, track had been laid to the village of Kadikoi and ammunition was being sent by truck, where a fortnight before shot and shell was being passed hand to hand down a line of men. Within seven weeks, the track had reached the 660-foot-high col on the heights above Sevastopol, 4½ miles from the coast. There was a branch line to the Ordnance depot, the Balaclava to Kadikoi line had been doubled and a network of lines lay across the plain, amounting altogether to 39 miles of track. Whatever Russell may have reported, it seems unlikely that men who worked at this rate had too much energy left for fighting between themselves. A splendid example of speed was on show in the building of a bridge across a stream. A pile driver was landed off a supply ship in the afternoon. It was taken that evening to the site in pieces, erected, set to work and within twenty-four hours, the piles were driven, the bridge was complete and the rails had already moved on another hundred yards. The London press as a whole had no doubt as to where praise was due. The Illustrated London News wrote in March 1855,

Navvies at Balaclava, photographed by Roger Fenton

It ought to be consolatory to Mr Carlyle and the mourners over the degeneracy of these latter-days, that there is at least one institution, and that a pre-eminently English one, which, despite climatic drawbacks and all sorts of deteriorating influences, exhibits all its original stamina and pristine healthiness – to wit, the British navvy. Everything we hear and read, from every quarter, testifies to the energetic, skilled, and matured progression of the great undertaking now progressing between Balaclava and the cannon-bristling heights of Sevastopol, and there cannot be a doubt that, when it has reached its terminus, those engaged upon it may safely adopt the motto of their honoured chief, Sir Morton Peto – Ad Finem Fidelis.

The line was completed well ahead of schedule. The navvies had worked night and day to complete the supply route for the Army – now it was the Army’s turn to use it. The Commissariat at once introduced regulations: no supplies could be sent before 8.00 in the morning or after 5.30 in the evening. The military had been vociferous to praise or damn the navvy army: one would dearly love to have heard the views of the navvy on the gentlemen of the other army, with their petty, bureaucratic rules. Beattie for one had worked ceaselessly once reaching the Crimea only to be injured in an accident on the line. He came home and died, as much from total exhaustion as from physical injury. The army wanted the navvies to stay on to help build new fortifications, but the contractors were insistent that they were there for civil duties only, though they had armed them with pistols just in case the Russians took a different view of their status.

The Crimean railway played a vital role in the war, shifting over a hundred tons of supplies a day up to the troops camped around Sevastopol. Seven months after the first rails were laid, the railways job was completed; in September 1855 the fortress fell. Peto received recognition for his part, and was knighted. The navvies collected their pay and moved on.

There was, however, one other railway engineer who made a contribution. The senseless carnage of the Crimea, exacerbated by the almost criminal incompetence of generals, horrified Isambard Kingdom Brunel. His first practical proposal was for a floating siege gun. This was a quite extraordinary device. The hull, largely submerged, was manoeuvred by steam jets which would allow the gunner to bring the weapon round to bear on the target. The gun itself was set in an armoured hemispherical shield that emerged above the waves. The vessel would be brought to the location in a specially adapted small-screw steamer ‘made to open at the bows and its contents floated out ready for action’. Brunel had just created the landing craft. Sir John Burgoyne was an enthusiast for the idea, but then the plans made their way to the Admiralty, a notorious home of reaction and mind-numbing conservatism. Brunel could only write to Burgoyne,

You assume that something has been done or is doing in the matter which I spoke to you about last month – did you not know that it had been brought within the withering influence of the Admiralty and that (of course) therefore, the curtain had dropped upon it and nothing had resulted? It would exercise the intellects of our acutest philosophers to investigate and discover what is the powerful agent which acts upon all matters brought within the range of the mere atmosphere of that department. They have an extraordinary supply of cold water and capacious and heavy extinguishers, but I was prepared for and proof against such coarse offensive measures. But they have an unlimited supply of some negative principle which seems to absorb and eliminate everything that approaches them.

When a messenger was later sent to retrieve the model, the Admiralty bureaucrat seemed not to have the slightest idea of what the model was for, and then, at last, he remembered it – ‘the duck-shooting thing’.

This print from The Illustrated London News gives a clearer idea of the railway at Balaclava, showing the very simple construction used with light rails and sleepers and no ballasting.

Brunel’s foray into military planning was a failure, but he turned to another aspect of the war. The Times reports, in particular, had highlighted the appalling conditions of the Crimea. In the winter of 1854-5 there were 25,000 British troops in the region, and 12,000 of these were in hospital. Those who were sent to the notorious sick quarters of Scutari had little chance of recovery. Frequently, it was not their wounds that were to kill them but disease bred in the filth of the hospital. The bureaucracy sat complacently by while Florence Nightingale alone campaigned for the sick and dying. She saw her main enemy as Sir Benjamin Hawes, Permanent Under Secretary at the War Office. He was ‘a dictator, an autocrat, irresponsible to Parliament’. The original immovable object, he was also Brunel’s brother-in-law, and in February 1855 the autocrat approached Brunel to ask if he would design a pre-fabricated hospital for the Crimea. Brunel replied immediately: ‘This is a matter in which I think I ought to be useful and therefore I need hardly say that my time and my best exertions without any limitations are entirely at the Service of Government.’

He set about designing a hospital complex based on standard units, each one of which would have essentials – a nurses’ room, water closets and out-houses. There was to be plenty of space for each patient, and a fan would blow air in for ventilation. There were wash basins, invalid baths, and a wooden trunk drainage system was provided. The majority of buildings were of wood, but metal was used for kitchen, bakehouse and laundry to avoid fire risk. In April, the hospital and staff were shipped off together. Brunel sent strict instructions:

By steamer Hawk or Gertrude I shall send a derrick and most of the tools, and as each vessel sails you shall hear by post what is in her. You are most fortunate in having exactly the man in Dr Parkes that I should have selected – an enthusiastic, clever, agreeable man, devoted to the object, understanding the plans and works and quite disposed to attach as much importance to the perfection of the building and all those parts I deem most important as to mere doctoring.

The son of the contractor goes with the head foreman, ten carpenters, the foreman of the WC makers and two men who worked on the iron houses and can lay pipes. I am sending a small forge and two carpenter’s benches, but you will need assistant carpenters and labourers, fifty to sixty in all … I shall have sent you excellent assistants – try and succeed. Do not let anything induce you to alter the general system and arrangement that I have laid down.

Throughout the planning, Brunel showed a scrupulous attention for everything from how to lay a floor to the provision of boxes of paper for the WCs. The one thing he could not have foreseen was the total absence of local labour to build the hospital. The gang of eighteen men sent over from Britain had to do it all themselves, and even with such a minute workforce they were able to admit the first patients just seven weeks after work began – a huge compliment to Brunel’s planning skills.

Railway engineers and railway builders were among the few who emerged with credit from the sorry mess of the Crimean War. Brunel’s hospital saved hundreds of lives, possibly thousands: of the 1500 sick and wounded who passed through the wards only fifty died. Little more than half of the hapless patients who entered the hell-hole of Scutari left it alive. The railway too saved lives, by shortening the miseries of the campaign. The war was a minor affair in railway building terms but it provided ample evidence of what practical men could do in the way of solving technical problems, wherever they might occur. Such talents were needed in good measure as railway building moved out of Europe to the rest of the world.