The Stourbridge Lion built by Foster and Rastrick, the first locomotive to work on an American railroad.

North America was the one area outside Europe which was also marching forward into the new industrial age. The Orders of Council of the Napoleonic Wars, ostensibly passed to deny France any commercial traffic, by denying the rights of any merchantman to carry goods to or from any French port or colony, acted against the rapidly growing merchant fleet of North America. When the United States emerged from the War of Independence it was largely an agricultural nation. In order to survive the embargo, the Americans were increasingly forced back on their own resources. Somewhat belatedly, the British Government appreciated its mistake. A Parliamentary commission reported, ‘It clearly appears that those manufacturers have been greatly promoted by the interruption of intercourse with this country, and that unless that intercourse be speedily restored, the United States will be able to manufacture for their own consumption.’ The comments were already too late: America was set on the road to self-sufficiency. Cotton mills and iron foundries were established, while inventive entrepreneurs such as Eli Whitney and Samuel Colt were establishing a system of manufacture using ‘interchangeable parts’, which was to form the basis for mass production. The go-ahead republic was never again to rely for long on the Old World of Europe for anything – and railways were no exception.

The first American railways, or railroads to use the local term, developed as in Britain to supplement the canal system. The most bizarre example of a canal and railway combination came on the Pennsylvanian main line canal; designed to link Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, it was begun in 1826. There was an all too obvious barrier in the way of canal construction, the ridge of the Allegheny Mountains which crossed the proposed line and rose to a height of over 2000 feet. The answer was the Portage Railway which crossed the mountains on a series of inclined planes and levels. The inclines were worked by stationary steam engines and the remainder at first by horses and later by locomotives. It was, in a sense, not unlike the Cromford & High Peak Railway in Derbyshire which linked the Peak Forest and Cromford Canals. But the Cromford & High Peak Railway used conventional trucks and carriages for its line: passengers on the Portage Railway went all the way by boat. The packet boats were split into two parts for the rail section and floated on to special wheeled trolleys. They then set off for a 36½-mile journey over the mountains, at the end of which the two halves of the boat were reunited and continued in a more conventional manner afloat. One of the early travellers on the line was Charles Dickens who described the boat as ‘a barge with a little house in it, viewed from the outside; and a caravan at a fair viewed from within’. The author was not over impressed by the sleeping arrangements. He ‘found suspended on either side of the cabin three long tiers of hanging book-shelves, designed apparently for volumes of the small octavo size. Looking with greater attention at these contrivances (wondering to find such literary preparations in such a place), I descried on each shelf a sort of microscopic sheet and blanket; then I began dimly to comprehend that the passengers were the library, and that they were to be arranged, edge-wise, on these shelves, till morning.’ Other canal-railway conjunctions were more conventional.

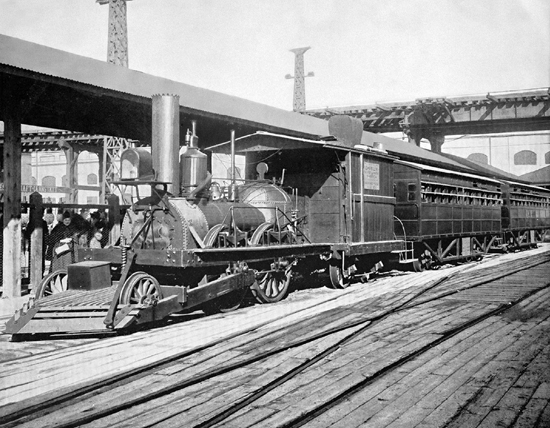

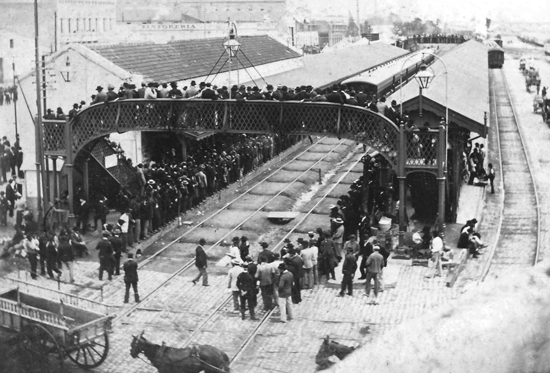

The Stourbridge Lion built by Foster and Rastrick, the first locomotive to work on an American railroad.

The canal that was to link the Delaware to the Hudson was built specifically to bring anthracite from the newly discovered coal fields of Pennsylvania. Work began in 1825. It was a fascinating canal, including one remarkable structure, a suspension aqueduct over the Delaware. The workforce was a mixture of German and Irish navvies who did not get on well together, indeed the Irish lived up to their reputation for hard work, hard drinking and hard fighting. One of the engineers John B. Jervis said in an interview with a local paper, ‘No canal was ever dug through pleasanter country – no swamps, or muck to contend with – no extremes of weather. But that doesn’t mean anything to these club-swinging Irish. I don’t know what they’ve got to fight about. They don’t need a reason; they fight just for the hell of fighting.’ Nevertheless, they pushed the works ahead at a great rate and by October 1828 over a hundred miles of canal had been opened, including 22 aqueducts and 107 locks. But the last fifteen miles from Dyberry Forks to the collieries was built not as a waterway but as a railroad.

In 1828 Horatio Allen, one of the young engineers on the project, was sent to England to purchase four locomotives from Robert Stephenson. In the event, he bought just one Stephenson locomotive and three from Foster and Rastrick of Stourbridge. The latter were somewhat primitive, very little different from the old Puffing Billy design, but it was one of these, the Stourbridge Lion, that was to haul the first train over American tracks. It was a lumbering giant, weighing in at 8 tons, twice the weight the railroad engineers had allowed for when building the track. Mechanically it was primitive, its vertical cylinders working a pair of beams with connecting rods driving straight down on to the rear wheels which were linked with the front wheels in an 0-4-0 arrangement. The combination of the large weight and the ‘hammer-blow’ effect from the vertical cylinders provided a strenuous test of the simple track. The engineer who purchased it, Horatio Allen, now volunteered to put it through its paces. He set off with the sublime confidence of the young and ignorant.

I had never run a locomotive nor any other engine before. But on August 9th 1829, I ran that locomotive three miles and back to the place of starting, and being without experience and without a brakeman, I stopped the locomotive on its return at the place of starting.

The line of road was straight for about 600 feet, being parallel with the canal, then across Lackawaxen Creek on trestle-work about 30 ft. above the creek, and from the curve extending in a line nearly straight into the woods of Pennsylvania.

When the steam was of right pressure … I took my position on the platform of the locomotive alone, and with my hand on the throttle-valve, said ‘if there is any danger in this ride, it is not necessary that more than one should be subjected to it.’

The locomotive having no train behind it answered at once to the movement of the valve; soon the straight line was run over, the curve (and trestle) was reached and passed before there was time to think … and soon I was out of sight in the three miles’ ride alone in the woods of Pennsylvania.

If it all seemed very satisfactory to Allen it looked a good deal less so to the spectators who had seen the simple wooden bridge over the creek sway and heard its timbers moan as the locomotive passed across. An examination of the track showed that a number of sections of rail were cracked and broken: it was Penydarren all over again, and the result was much the same. The Stourbridge Lion had roared twice, but now it was driven off into a shed and left to rot. America’s first steam railway experiment had not been a resounding success. It was, however, no time at all before steam was again given an outing. The Baltimore and Ohio Railway was opened in 1830 using horses at first for both freight and passenger traffic, but soon turning to the locomotive. There were to be no British imports here, however; instead a local man, Peter Cooper, designed a curious little engine, aptly named Tom Thumb, a very lightweight affair with a vertical boiler, very reminiscent of Novelty, the unsuccessful finalist at Rainhill. It weighed a mere ton, and a contemporary print shows it racing against a horse-drawn rail bus, with a number of top-hatted gentlemen actually riding on the locomotive itself. It worked but it can hardly have worked well since the company went on to experiment with sails as an alternative to steam. At much the same time, Edward L. Miller was trying out another American designed and built locomotive, the Best Friend, on the South Carolina Railway. It rattled along at a very respectable speed of around 20 m.p.h. with five coaches. What is significant about these American locomotives, however, is not their performance, but the fact that they owed so little to the pioneering design technology of Britain. True, Robert Stephenson was supplying a few locomotives to American lines, but local engineers were posting notice that they were intending to go their own way in all aspects of railway construction – track, locomotives and rolling stock. The British, perhaps on the defensive, were inclined to be snooty about the American system. Daniel Gooch, the famous locomotive designer of Brunel’s Great Western, took a train from New York to Niagara Falls in 1860 and was not impressed.

Railway travelling in America is wretched; their republican notions of having only one class makes your company very mixed, and the carriages being all large open saloons with a door at each end and passage down the middle, prevents you having the slightest privacy even if you were a good large party of your own. The roads are dusty and the use of wood for fuel sends a quantity of charcoal into your carriage, mixed with the dust, so that when you have travelled all day you are as black as a sweep.

He complained that during the journey he was reading a book and the man behind not only started reading it but complained that Gooch was turning the pages too quickly. Gooch, with an air of hauteur that one can all too easily imagine, handed the book over without a word. But then, there was nothing about America that Gooch did like.

I think I was never so entirely glad of any thing as I was when I felt, on that day, that our ship’s head was turned towards England and I was quit of America.

Gooch was eyeing the American railroads in the light of his own experience, and found them wanting. He did not seem to appreciate that what suited the GWR did not necessarily suit a young country, still advancing its frontiers. The US system was to build up in a way that suited the railways of a continent, and it was to have a profound affect on all railway development in both North and South America. The surprise, in retrospect, is not that the local American experience was so crucial to development, but that anyone else got a look in at all. If there was to be a strong British influence it would logically be felt north of the 49th parallel in Canada.

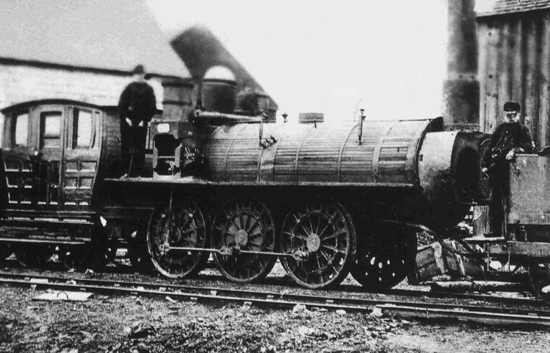

A working replica of John Bull built for the 1940 New York World’s Fair. The original was built by Robert Stephenson & Co. for the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1831.

Canada was both like its southern neighbour and very different. It was similar in that it was a vast territory, much of it unexplored and only a small part settled. It was dissimilar in that there had been no revolution, and the country was still tied to Europe. If these were the only differences then railway building could have gone ahead at a reasonable pace. They were not. To put the story in context needs a brief resume of the country’s history.

British and French were casting their nets off Labrador and Newfoundland as early as the sixteenth century and soon traders were making their way up the St Lawrence to deal in furs with the Indians. The peaceful trading days were short-lived as the traders pushed on aggressively into Indian territory and there were wars with the Iroquois and the Huron. In the seventeenth century the French established the Compagnie des Habitants on the St Lawrence, a base which was to develop into the city of Quebec, and from there they traded ever further west. These free ranging ‘voyageurs’ were the first to call themselves Canadians. One of the old voyageurs told of his old way of life with great enthusiasm:

I have had twelve wives in the country, and was once possessed of fifty horses and six running dogs. I beat all Indians at a race, and no white man passed me in the chase … Huzza, huzza pour le pays sauvage.

The British were altogether more sedate, but a good deal more wide-sweeping in their claims. The Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson Bay coolly laid claim to the whole drainage basin of Hudson Bay, a mere million and a half square miles. The static English, snubbing the native Canadian Indians, formed a marked contrast with the free-ranging French. When conflict came, however, it was precipitated by war in Europe rather than any local difficulties, although the end result was the same. Quebec fell and the French Canadians found themselves under English rule. There was a continuous move westward. On 22 July 1793, Alexander Mackenzie was able to write on a rock that he was looking down on the Pacific Ocean. Other explorers such as Fraser of Fraser Canyon and David Thompson helped establish trade routes to the west. But these still depended on rafts and canoes and pack animals. The main centres of settlement remained in the east, divided between Upper and Lower Canada. There were local elected legislatures and an imposed overruling council appointed by the Crown in London. There was a population divided among the French settlers and their descendants, English, Welsh and, increasingly, Scots and Irish – the latter driven from their old homes by poverty. Added to these was a sizeable minority who had come north after supporting the losing side in the American War of Independence. Canada was partly settled, partly wild, partly self-governing, partly controlled as a colony and its thinly spread population was a mixture of often antagonistic nationalities. It was not a recipe for getting things done in a hurry. The slow and muddled start to railway building grew out of this confused background.

In some ways, the early history of Canadian transport was very like that of the USA: navigable rivers were the key that linked the settlements together, but it was the natural wealth of the forests that drew settlers to a region in the first place. Thomas Need, writing on the Canadian economy in 1830 put it neatly:

The erection of a sawmill is the first event in the formation of a settlement in the bush. It induces others to come to the neighbourhood since it offers the facilities of building timbers. Thereafter some bold man is persuaded to erect a grist mill. A store is opened, a tavern is licensed and a village has sprung up in the heart of the forest.

Rocket, not the famous Stephenson engine, but one built for the American Reading Railroad by Braithwaite, Milner & Co. of London in 1938.

These communities created rough roads down to the nearest navigable river and a system of canals, log flumes and chutes to move the timber. Winter brought everything to a halt. Thomas Coltrim Keefer, an early protagonist for railway construction, painted a dramatic picture of the frozen land:

Old winter is once more upon us and our inland seas are ‘dreary and inhospitable wastes’ to the merchant and to the traveller. Our rivers are sealed fountains and an embargo which no human power can remove is laid on all our ports … the animation of business is suspended, the lifeblood of commerce is curdled and stagnant in the St Lawrence, the great aorta of the north.

Even in summer transport was problematical. There had been advances from the age of the canoe: the first steam boat had puffed its way down the St Lawrence in 1809, powered by a Boulton and Watt engine, to be followed by a second on the Ottawa River, a year later. The rivers were, however, not navigable throughout their lengths and there were long portages where goods had to be carried round rapids and shallows by man, pack animal or cart. River routes were also notably devious. Traffic from New York to Montreal, for example, went up the Hudson River, through Lake Champlain into the Richelieu River to the St Lawrence at Sarel, and then on a last leg of 40 miles up the St Lawrence to Montreal. Yet overland the route from the Richelieu to St Johns, opposite Montreal, was only 14½ miles – a total saving of 90 miles of river travel. Here was an obvious case for a railway, and the land was flat as could be, presenting no problems of construction. But when it came to framing the Bill for the Champlain and St Lawrence Railway, the legislators took their job very seriously. There were innumerable clauses, one of which contained a sentence of 1453 words! If written out on a strip it would have stretched nearly 50 yards down the tracks. The Canadian businessmen who had shouted loud and long for the railway had the satisfaction of seeing the Bill passed in 1832. When it came to paying for the line, however, they became rather quiet and the money was not raised until 1834 when work finally got under way.

This was an American-Canadian enterprise, and it seemed sensible to employ American engineers to construct the line. However, it was to tried-and-trusted Robert Stephenson of Newcastle that they went for the first locomotive. Here two traditions clashed. James Hodges, who left England to work on Canadian railways, described the American system of building as one where economy ruled. ‘With this object in view, timber is universally substituted for the more costly materials made use of in this country. Tressel bridges take the place of stone viaducts, and, in places in which in this country you would see a solid embankment, in America a light structure is often substituted.’ He might have added that American practice did not call for the well-levelled, well-ballasted track that was de rigeur in Britain. Stephenson sent over one of his 0-4-0 Samson class locomotives which on 21 July 1836 rocked and rolled its way down the lumpy track. The rigid frame designed for smooth British track was far from suitable for the new circumstances it was now meeting. The first steam railway in Canada was not an immediate success, and for a short while horses had to be brought in for haulage. The clash between British and American practice would occur again.

The next portage railway also featured Montreal. The city had grown up at the point where the river navigation had ended at the Lachine Rapids which dropped the river down 46 feet from Lake St Louis. They had been bypassed in the eighteenth century by a coach route and in 1825 by a canal. Now a Scots-Canadian, James Ferrier, was to promote a railway. Perhaps encouraged by lingering loyalties to the old country he brought over Alexander Miller, Chief Engineer of the Dundee & Arbroath Railway, to survey the route in 1845. He followed the line of a stream the Petit Lac St Pierre which meandered harmlessly until it spread out to form a wide area of marsh near Recollect Gate. Miller decided that spoil excavated from the nearby Lachine Canal would do admirably to fill the bog. In the event thousands of cartloads of earth and stone were needed, reinforced by extensive piling, to produce a solid strip along which track could be laid. Even so it remained a perilous place, as was dramatically illustrated in an accident of 1855. A locomotive jumped the rails, landed in the bog and slowly and inexorably vanished from sight. The line was opened in 1847 with two American locomotives, but in 1848 two new engines arrived from Scotland with 72-inch drive wheels that provided new power. Fired by patriotic pride, Miller himself took the regulator on the inaugural run and the little train dashed off to reach the terminus 7 1/2 miles away in just 11 minutes, at an average speed of 45 miles an hour. The passengers were terrified and at first demanded to be taken back by road. Miller pacified them by promising to behave himself on the return journey. They reluctantly agreed, and nine minutes later they were back at the start.

Samson the locomotive built by Timothy Hackworth for use in Nova Scotia.

The route west from Montreal was via the Ottawa and Mattawa rivers, which had involved the old canoeing voyageurs in forty-seven major portages along the way, though this number was later cut by canal building. A number of portage lines were built, and as they were seen simply as links between steamer piers, there was no need for them to be consistent, so that the Carillan and Grenville was built as a broad gauge, while the little line bypassing the Chat falls was only 3 ft. gauge. One portage line started out with pretensions to become something altogether grander. The Montreal & Bytown Railway was intended to be part of a mainline route from Montreal up the Ottawa valley to Bytown, later renamed Ottawa, 100 miles of main line, with 23 miles of tramway feeders. When work began in 1853 the contract for building went to an Englishman, James Sykes of Sheffield, who brought in the brothers William, Samuel and Charles de Bergue of Manchester to help. The sensible decision was taken to begin on a short portage section, from Carillon to Grenville, which would bring in traffic from the steamer trade as soon as it was opened. When that was successfully completed Sykes returned to England confident that he could raise the capital to fund the line. His confidence was well founded and when he boarded ship he had £50,000 in cash with him. Then disaster struck: the ship foundered and James Sykes and the funds were lost. The company back in Canada was now in debt, but when it was put up for sale it only fetched $21,200. In 1854 a single locomotive was bought to be joined by a Birkenhead locomotive in 1858. And that was to be the last purchase of locomotives, or indeed very much else, that the company was ever to make. Up and down they chugged between the two piers, until the steamers no longer ran and nobody wanted the now antiquated service. In 1910 after more than half a century of continuous use, the two veteran engines were finally retired.

The history of the portage railways was full of similar stories of lack of funds, lack of equipment or both. Even the few non-portage lines that were attempted came to grief as well. A route was planned to run south from Bytown (Ottawa) to the American border at Prescott, where it was to link with the US line, the Ogdensburgh & Lake Champlain Railroad. Work began in 1851 and the going was not difficult, though the way did lie through uncharted woodland and scrub. Rails were ordered from South Wales and shipped across the Atlantic, but in the event there was not enough of them and no cash to buy more so the line was completed using wooden rails with an iron strip tacked on the top – which would have been quite acceptable in the 1750s but was decidedly odd in the 1850s. Over this flimsy structure the first train duly ran.

There was one lonely outpost of railway building in Nova Scotia where a line was built to serve the local coal mines. This line would certainly have seemed familiar to anyone visiting Canada from the north-east of England. It was begun as a tramway running from the pits to the East River of Picton. In 1834, when trade was increasing, it was decided to establish a new wharf and build a railway to be worked by locomotives. A local man, Peter Crerar, who had come to Nova Scotia from Scotland as a schoolteacher in 1817, agreed to try a preliminary survey and the plans were duly sent off to the Railway Board in England. Back came a letter: ‘What need is there of our sending you an engineer when you have Mr Crerar in the County? Let him supervise the construction.’ And so he did. H.S.Poole of the Canadian Society of Civil Engineers was later to write a report on the plans, in which he confirmed the sound quality of the survey work. The line was built in awkward hilly country, yet the steepest gradient was 1 in 360, and although a good deal of cutting was involved to achieve it, no curve was more than a 4° radius. The hypothetical English visitor would have been equally at home with the three locomotives that opened the service. They were sent from Shildon by Timothy Hackworth and were typical of his work at that time. What makes them seem so odd to modern eyes is the return-flue boiler, as used in the famous Rainhill locomotive, Sans Pareil. The rest of the manufacturers had moved over to the modern multi-tube boiler, but Hackworth still had his one giant tube bent round in a U-shape. This meant that the grate was next to the chimney, so that the driver stood on his platform at the back of the engine, while the fireman stood at the front – which can hardly have been very good for communication. The sanding system was what we would now call low-tech’. Each end of the loco had a bucket of sand and the driver would throw out a handful if the engine needed to go forward, and the fireman performed the task when going in reverse. The driver of the first engine to be used, Samson, was an Englishman who had helped to build it in Durham, George Davidson. And he stayed on driving it right up to 1882. The old engine was rescued from the scrap heap and given a place of honour at the great Chicago Exhibition of 1893.

Robert Stephenson: the engineer responsible for one of the finest example of civil engineering on Canadian railways.

The early years of railway building in Canada were entirely piecemeal and notably lethargic. In 1850 Britain had 6621 miles of track, but had already been overtaken by the USA with 9021: Canada could master a paltry 68 miles. There were reasons, some of them political – the Province of Canada was not formed until 1841 which delayed development as railway promoters were faced with a variety of different authorities. Then there was the problem created by the fact that so many Canadian settlements lay very close to the American border. St Andrews in Nova Scotia promoted a 250-mile-line to Quebec, a charter was granted and in 1836 the British Government promised a subsidy. But the line ran through Maine, an area being disputed by the British and American governments: the US formally objected to the line, and the scheme collapsed. It did not, however, dampen Nova Scotian enthusiasm for railway promotion. Joseph Howe was a man of vision who saw a railway from Nova Scotia as an essential extension of the transatlantic steamer trade – much as Brunel had seen his steamships extending the Great Western Railway from Bristol to America. Howe, with what was soon to appear characteristic optimism, named the proposed company the ‘European & North American Railway’. Knowing that he would never raise the necessary funds in Canada, he set off for England where the authorities showed not the least interest in his schemes and sent him packing, or so they imagined. They had underestimated Howe: if government would not listen, then he would appeal directly to the people. He held a series of public meetings in which he stressed the advantages to Britain of a soundly based immigrant route and a route out for Britain’s manufactured exports which would be balanced by the outgoings from the cornucopia of Canada’s rich farmlands. He was an outstanding orator and a press report of the time described his ‘lucid reasoning, startling facts, profound political philosophy and forcible eloquence’. His political philosophy was certainly unusual for the time: he wanted the government to own and run the railways; what is more he thought that railways, like roads, should be free for all. ‘Government ownership’, he argued ‘would keep down the rates and would save the people from the private greed which is at the time so manifest in the conduct of English lives.’ While the government of Victorian England was unlikely to listen to such ‘dangerous’ doctrines, they were at least forced, by public opinion, to take the European & North American Railway seriously. In 1851 they agreed to guarantee a loan.

Howe had scarcely time to congratulate himself on a job well done before fresh problems appeared. A faction in New Brunswick still wanted a through-route that would include a section of the USA, as opposed to the northern, more Canadian line, favoured by Howe. There was a great deal more wrangling before an unfortunate compromise was reached. The new Brunswickians, at that time still detached from Eastern Canada, were to build their own line at their own expense: the Canadian provinces were to be responsible for their own individual sections. So there were to be provincial railways paid for by local government with the backing of the imperial government, whose only link would be via a private railway which might – or might not – be built in a neighbouring country. It was also a remarkably ambitious project, calling for the construction of 1400 miles of track through difficult country. How this bizarre project would have fared if work had begun, we shall never know, for other characters joined in who were to change the plot of the story.

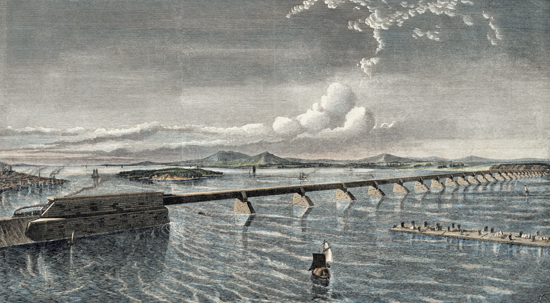

Victoria railway bridge across the St. Lawrence under construction. The design is based on Stephenson’s earlier bridge across the Menai Straits, in which the trains actually ran inside the vast box girder.

Among the advocates of the European & North American Railway was Sir Francis Hicks, a senior minister in the Canadian government. In 1852 he met William Jackson of the great contracting company Jackson, Brassey, Peto and Betts who knew something of the scheme for Howe had already put his plans to Sir Morton Peto. The emphasis now shifted back from public financing to private money. The bankers Baring Brothers and Glyn Mills made it known that funds were available for railway construction, while at the same time the contractors offered to build the entire line. If ever there was evidence of the power and scale of operations of the great contractors then here it was: their terms were simple, but staggering in their magnitude. The government was to pay half the costs and for the other half Jackson, Brassey, Peto and Betts would accept a grant of six million acres of crown land and an annual payment by the railway company of £100,000 for twenty years. There now followed a long period of wrangling. There were local interests pursuing local ends, and a strong and growing groundswell in favour of a major – the major – Canadian Railway being built by Canadians, not by British interests, however eminent. In the clamour of argument, the grand vision of a main line sweeping majestically across Canada was lost. All was fragmented, and what emerged at the end was a line split in two: the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada, and the Grand Trunk Railway of East Canada. In the event the Grand Trunk was to be promoted in Britain with funds coming from Baring Brothers, Glyn Mills and Peto and his associates and other funds were supplied by the Canadian Government and Canadian shareholders. Of the 900 miles of railway to be built, the Peto consortium was to be responsible for 300. Standards were set high. This was to be, in the official language of the Charter,

The completed Victoria Bridge.

a first-class single-track railway, with the foundations of all the large structures designed for double track, up to the earth level, and to be superior to any Canadian or American railway now known or used, and equal to the first-class English railways.

This insistence on excellence was not the result of careful thinking about the type of railway best suited to the terrain, but was intended to silence critics. Local interests were pandered to, so that not only was the line being built to join up with the still non-existent New Brunswick route but there was also to be an extension to Trois Pistoles on the south bank of the St Lawrence and the plans included what would inevitably prove an expensive river crossing at Montreal. All this was being justified by profit assessments that seemed to owe more to optimistic crystal ball gazing than to rational analysis. A major railway system that should have been considered as a long-term involvement was being promoted in terms of short-term gains. It was attracting the get-rich-quick speculators who had been such a prominent force in British construction – a group that was quick to invest funds – and just as quick to withdraw them. It was not a good beginning.

The English contractors were responsible for the line from Toronto to Quebec, and things went wrong almost from the start. The surveying team travelled on horseback to select the line, and controversy soon arose. It was in the contractors’ interest to make the line as cheaply as possible; it was in local community interest for it to reach as many towns as possible. The selected route included some heavy gradients and missed some towns along the way by several miles. The contractors’ argument was that this saved the huge expense of cuttings and embankments. Local people replied that cuttings and embankments had been allowed for in the estimates, so could they have their line please? Sometimes the contractors won, sometimes the locals triumphed as at Port Hope where the rails were brought to the town on a viaduct across the river.

The early work of laying rough track for contractors’ trains went largely to Canadian sub-contractors, but skilled men –masons, quarrymen, engine drivers and fitters – were brought out from England at good pay, ranging from 4 shillings a day for the navvies to 10 shillings for the highly skilled, twice what they could expect to get at home. Expenses were mounting, and funds in Britain were being hung on to very tightly in the uncertain times of the Crimean War. But a war which was bad news for Britain brought good tidings to Canada. As the suppliers of Balkan timber and Ukraine grain were brought to a halt, so the lumber camps and grain fields of Canada prospered. And the steadily advancing lines were constantly bringing fresh opportunities for development. There should, it seemed, have been ample funds in Canada, but local opinion was turning against the British contractors. At first, it was taken as a matter of pride that the line was to be built to the exacting standards of the very best English routes. Americans simply spiked their rails down to the sleepers; the British held the rails in metal chains and used wooden wedges for a firm grip. The American system had a certain spring to it, whereas the British was altogether more rigid, and hence there was a strong tendency to cracking in very cold weather. What once looked like quality now seemed more like extravagance. American engineers used materials that were available locally, and were providing ever grander and more complex timber viaducts. The Canadian line was passing through forest almost throughout its length, yet prefabricated iron parts were being sent over from the specially established Canada Works at Birkenhead on the Mersey. Rumours flew that Canadian officials had been bribed with share offers to hand out all this lucrative work to the men from England. Had they known just what lay ahead, Brassey, Peto and Company would probably have bribed officials to be released from their contracts.

At first, the idea had been to rely on local workers, but there were simply not enough. Brassey came over in person to inspect the works and suggested that French Canadians should be recruited from Lower Canada. English and American gangers were given a guinea a week for each man they signed up and there was soon a good sized workforce. They were not, it soon appeared, an especially useful workforce.

They could ballast, but they could not excavate. They could not even ballast as the English navvy does, continuously working at ‘filling’ for the whole day. The only way in which they could be worked was by allowing them to fill the wagons, and then ride out with the ballast train to the place where the ballast was tipped, giving them an opportunity of resting. Then the empty wagons went back again to be filled; and so, alternately resting during the work, in that way, they did very much more. They could work fast for ten minutes and they were ‘done’. This was not through idleness, but physical weakness. They are small men, and they are a class who are not well fed. They live entirely on vegetable food, and they scarcely ever taste meat.

Even so, they were extra labour, when extra labour was desperately needed. Without their help, many of the experienced navvies could easily have packed up and gone home. Towards the end, mechanical power was brought in to help muscle power. Steam excavators were commonplace in America, but were scarcely used at all in Britain, and the man on the spot in Canada, Mr Rowan, clearly never warmed to the steaming beasts.

Towards the last, in consequence of the extreme cost of labour, we employed steam excavators, not because they were cheaper than men, but because they supplied the want of labour, and enabled us to get on faster. A steam excavator is found to be profitable only in very hard material, such as hard pan, in which a very large force is required to excavate. In lighter materials such as sand or gravel, it is more expensive to use than men at five or six shillings a day.

There was one other factor which the British had failed to take into account, the severity of the Canadian winter. In Ottawa the average temperature between the end of November and the beginning of March is only 16°F (— 10°C). Rivers freeze, the ground freezes, snow falls and stays where it drops and outdoor work on railways comes to halt. Costs worked out in the comfort of England looked very uncertain in the ice-locked forests of Canada.

There were difficulties all along the line, but by far the greatest task was the construction of the bridge across the St Lawrence at Montreal. The consulting engineer for the project was Robert Stephenson who had built two bridges in Wales to his own revolutionary design, the first at Conwy, then one across the Menai Straits between the Welsh mainland and Anglesey. Strength and rigidity was provided by the tubes themselves, in effect very long iron boxes; the novel feature was that whereas with most bridges the trains run over the girders, here they ran inside them. Piers were prepared, the two tubes were assembled on site from prefabricated sections, then when all was ready they were floated into position and jacked up. Both the Welsh bridges were a triumphant success. There was, however, a difference in scale. The Menai bridge, the larger of the two, was 1800 feet long; the St Lawrence Bridge, later to be named the Victoria Bridge, was to be 6512 feet long. The St Lawrence itself offered one advantage: the river was shallow and ran over a bed of rock, so there were good foundations for building the piers. Balanced against that was the great winter freeze, and when the thaw set in the builders had to contend with a swift current running in summer at around 8 knots. But engineering difficulties counted for little when set against the human difficulties met by the men who came to build it. The whole story was told in detail by James Hodges who was present throughout the construction period.

A replica of John Malsom. The original was built in 1847 for the Montreal & Lachine line in 1847 by Kimmonds, Hutton & Steel of Dundee.

The idea for the bridge had first been suggested by a Canadian, John Young, who approached Alexander McKenzie Ross who had been involved in the building of the Conwy bridge. Ross prepared plans which he then took to England to show to Stephenson in the spring of 1852. That autumn Stephenson visited the site himself, approved what he saw and made arrangements for Ross to be appointed as resident engineer. Stephenson himself returned to England to prepare the detailed plans. The tube was to be built in twenty-five sections which were to rest on twenty-four stone piers, and the bridge was to stand 60 feet above the high summer water level at the two spans crossing the navigable channel. The approach at either end was to be along stone-faced embankments. The Victorians were great lovers of accumulated statistics, and on this occasion the figures really do give a notion of the magnitude of the operation:

Total length of the tubes, 6,512 feet

Weight of iron in the tubes, 9,044 tons

Number of rivets in the tubes, 1,540,000

Number of spans, 25; viz. 24 from 242 to 247 feet each, one 330 feet

Quantity of masonry in piers and abutments, 2,713,095 cubic feet

Quantity of timber in temporary works, 2,280,000 cubic feet

The force employed in construction included 6 steam boats and 75 barges, representing together 12,000 tons, and 450 horse power

3,040 men

144 horses

4 locomotive engines

The iron work was prepared at Birkenhead and drilled ready for assembly under the supervision of Robert’s cousin, George Robert Stephenson. To pile on a few more statistics: the centre tube consisted of 10,309 separate pieces, drilled with half a million holes and each piece fitted perfectly and every hole was in place. Human and natural elements were not so easily controlled.

The forces which any bridge across the St Lawrence has to withstand are immense. Ice begins to appear in December in places where the flow is gentle. Then as winter cold deepens the ice begins to accumulate in great masses several feet thick which at any moment, perhaps caused by a temporary thaw, may be released from their resting place to thunder down the stream. Gradually the ice packs together to form a solid immovable mass that spreads from bank to bank and there it stays until the thaw. Then, once again, it breaks up and the floes continue their crashing journey downstream until the thaw is complete. The piers of the bridge had to be designed to take the pressure of the tubes, the equally strong pressure of winter ice and the impact of the careering floes. They were given substantial masonry centres to withstand the pressure and needed well-shaped cutwaters to deflect the ice-packs. A very obvious first requirement was a source of good stone. The best stone turned out to be in Indian land, so a meeting with the Indian occupants was arranged for a Sunday afternoon. Thirteen chiefs arrived, in full regalia of paint and feathered head-dresses, but the British engineers found them to be a rather sorry sight – old, careworn and dirty. Colonial expansion had not been kind to the country’s original inhabitants. The Indians in their turn were equally unimpressed by Hodges, the principal negotiator, who they considered to be far too young to be taken seriously – he was in fact over forty years old. Agreement, however, was reached and quarries opened at Point Saint Claire, 16 miles west of Montreal but only half a mile from the line of the railway. Work could begin.

On 24 May 1854 the first temporary dam was begun. Caissons, 188 feet long and 90 feet wide were towed out into the channel and sunk, they had to be pumped out, refloated and towed away again each winter to prevent the ice from wrecking them. It was not, however, to be the practical difficulties of the work that made for slow progress. Disease haunted the workings. In winter, the men who had come over from England and were wholly unprepared for the conditions, suffered dreadfully. Many suffered from frostbite of noses, ears and feet. The fine snow blowing into their faces combined with the brilliance of the sun caused temporary blindness. Summer offered no respite. Along with the warm weather came ‘ship fever’ or cholera and at one time as many as one in three were laid low. A great many never recovered. Hodges recorded his dismay at the number of strikes: ‘Besides strikes occasioned by other causes, it is almost a custom in Canada for mechanics and labourers to strike twice a year, let the rate of wages be what it may. The first period of general strike is in the Spring when increased activity in every business is occasioned by the arrival of the Spring fleet. The second is at commencement of harvest, where there is abundant demand for labour.’

Construction of the Pojucca tunnel on the Bahia to San Francisco railway engineered by Vignoles

Hodges also faced technical problems. Before leaving England he had left plans for a ‘steam traveller’ which was to be used for shifting stone at the site. A machine was duly built, shipped to Canada and found to be totally useless. The expensive machine was abandoned and one of the sub-contractors, Mr Chaffey, built a new one in the winter of 1854-5. It had none of the finished elegance of the English machine, but it had one distinct advantage – it worked. It was, in effect, a travelling crane running along rails on a 50-foot-high gantry, and it made the moving and sorting of the huge blocks of limestone a comparatively simple matter.

The principal difficulty, however, was cash. The Crimean War had sent prices rocketing and made nonsense of estimates. However, the contractors pushed on as fast as they could and in 1859 the bridge was open. Hodges now praised the engineer, contractors and their workforce: ‘They have left behind them in Canada an imperishable monument of British skill, pluck, science, and perseverance in this bridge, which they not only designed, but constructed.’ They also left behind a fortune spent in construction and the contractors took home a considerable loss rather than the expected profit. There was a general feeling that this was not a sensible way to build railways in Canada. Old world technology did not necessarily have the right answers to New World problems. The problems of the steam traveller were symptomatic of what the Canadians saw as a more general malaise. Why order machines, ironwork or, indeed, skilled men from abroad when all were available more conveniently and at lower price closer to home? Increasingly they looked to American experience as a more reliable guide to Canadian development than that offered by the very different railway world of Britain. And British engineers found that as they travelled the world as peripatetic railway builders they too met circumstances where America offered a more useful model. Laying out a line among the green fields of Kent was not at all the same as setting out a route through dense uncharted forests. James Robert Mosse wrote a short treatise on The Principles to be Observed in the Laying Out of Railways in Newly Developed Countries. In densely forested areas there was, in his opinion, ‘no better method than that practised in America’.

The party generally consists of four surveyors with from twelve to twenty men as chain-men, axe-men, carriers of baggage, &c; they are furnished with tents and provisions, and where practicable with two or more horse-teams. The surveyors include the chief of the party, the theodolite man, the leveller, one man taking cross-sections, and one spare surveyor.

After obtaining what knowledge of the country is practicable from its general features and from the course of rivers, the chief reconnoitres with an aneroid and a compass some 2 or 3 miles in advance of the party, and he then directs the courses to be taken with the trial lines. The theodolite man then cuts these courses in straight lines (not trusting to the compass) puts in pegs every 100 feet, enters in his notebook the courses, width of rivers and streams, and sketches the general topography of the country. The third surveyor records the levels, and the fourth man follows the level, taking at every 100 feet length cross-sections with a clinometer graduated to percentages of inclination, so that if the index mark 6, and the distance be 400 feet, the difference of level between the two points would be 24 feet; and a figured sketch of each cross-section is then entered in the note-book. By this system, the line cut through the forest is levelled and cross-sectioned on the same day; in fact, the ground covered by the cross-sections is thoroughly ascertained. Where the forest is not too thick, an average of 1¼ mile of line can be thus surveyed in one day, provided the axe-men and chain-men are experienced.

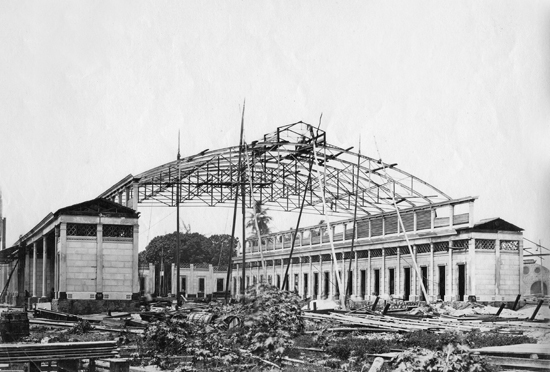

Bahia station under construction, 1861

The engineering world of the nineteenth century was being turned on its head. The British engineer was no longer teaching the newcomer overseas, he was learning from him. And when it came to railway construction in South America, British and US engineers and contractors were to find themselves in direct competition. And, at times, they found themselves faced with conditions for which even Mr Mosse’s carefully formulated rules proved quite inadequate. Yet a visitor to South America could be forgiven for believing that all the local influences were British. Visit the Central Station at Montevideo and the stony faces that frown down on you are those of James Watt and George Stephenson. The station at Sao Paulo in Brazil is based – loosely it has to be said – on the Houses of Parliament at Westminster. And nowhere is British influence more obvious than in Argentina. The vast curved roof of the Retiro Station at Buenos Aires is held up by ironwork supplied from Liverpool, while the tiles that decorate the booking hall at the Central Station come from Royal Doulton. Out in the country, in the great wild plains of the pampas are little half-timbered stations that seem to have strayed from Surrey. The first railway to be built in South America, admittedly a very minor affair, was in British Guinea and opened in 1848. Impressions are misleading, however: it is, in reality, a more complicated story in which money provides the main theme.

Retiro station, Buenos Aries at the end of the 19th century.

The first thoughts about railway building in the South American continent had a marvellous breadth of vision; nothing was excluded. In 1827 an Englishman resident in Brazil, Charles Grace, sent a petition to the Emperor for permission to build an ‘Iron Rail Way’ from Rio to Itaqui on the Argentine frontier. He was promised that his proposal would be given careful consideration. Documents accumulated steadily over the next ten years, each carefully filed and docketed, but nothing actually happened and eventually the project died, smothered under a blanket of paper. Then in 1836, the Government of Sao Paulo granted a splendidly all-embracing concession for ‘ways of iron or others of the most modern and perfect invention, or canals, or one thing or another’. Vehicles to use this nebulous transport system could be powered by steam, and if that was unacceptable they could be steamless. It would have required a deal of ingenuity to devise a system that did not fit the bill. There was even provision for a system to be worked entirely by stationary engines to cross the range of coastal mountains. At least engineers were encouraged to come and see for themselves, and shortly after the granting of the concession the British engineer Alfred de Mornay arrived to carry out the first railway survey in the country. Others soon followed and a range of proposals was put forward including one for a system powered by ‘elastic water vapour’. Real progress looked likely when an English merchant based in the port of Santos, Fred Forum, proposed a line from there to Sao Paulo. Matters advanced far enough for a consultation with Robert Stephenson after a cursory survey had been made. The proposed route was undeniably direct, but achieved this by charging headlong at the hills bordering the coast. Stephenson proposed a longer and gentler route along a river valley.

What is of the greatest importance, it is entirely free from works of magnitude, such as render an accurate calculation of expense not only extremely difficult, but absolutely impracticable, for throughout my experience I have found that the application of ordinary estimates to works of extraordinary magnitude is worse than useless, as it never fails to mislead. This remark is peculiarly applicable to your project, for you are preparing to execute work in a country where the facilities are not only few but limited, where the simplest and cheapest, rather than the most refined and expeditious, methods of operation must be made available.

The advice scarcely mattered since neither line was followed. Shortly afterwards in 1845 another British merchant, Thomas Cochrane, was given a concession for a track to Sao Paulo. All he had to do was raise the money, and he proved himself nothing if not enthusiastic in this regard. He decided he needed a gimmick to pull in possible investors, so he toured the country with a circus using a clown to hand out prospectuses. Whether the Brazilians felt that a railway promoted by a clown lacked gravitas or whether they thought that any railway promoted in Brazil was a bit of a joke is uncertain. In either case, no funds materialized. Eventually legislation was needed to create a climate in which work could actually get under way. The government agreed to make land freely available, and not just enough land to provide space for the tracks. There were land grants along the route, designed to encourage development, and a strip 30 kilometres wide was declared a no-go zone as far as other railway promoters were concerned, ensuring that the pioneers would not be challenged by rivals. New schemes began to appear.

Building the Johannes viaduct on the Bahia to San Francisco railway.

The main problem all the early would-be railway builders came up against was the line of hills running parallel to the coast and rising to a height of nearly 3000 feet, the Serra do Mar. Even road builders found them a major obstacle. Communication between ports on the coastal plain was comparatively simple, but routes inland were another matter. Mule tracks were the main form of transport and long lines of the beasts, each carrying loads of around 250 lbs, would toil up the steep slopes. That was when they were passable at all. In the torrential tropical storms of the region, exposed surfaces were open to the erosion of the rain: rocks were washed away and deep gulleys were carved into the hillside down which the water thundered. When a small town, Petropolis, was established at the top of the Serra as a summer retreat for the court and high officials, a decent road was created to reach it. An idea of the likely cost of rail building can be gauged from the fact that this roadway was costed, by the government, at £40,000 per mile, even when the land came free.

There was, however, a case for a line that would ease the journey along the sandy, dusty plain at the foot of the Serra. A concession was granted to Senor Ireneo Evangelista De Sorze (later Baron Mava) to build the line. William Bragge was brought over from Britain in 1851 and he opted for the 5 ft. 6 in. gauge then in use in Spain. In 1852 before the line was complete Bragge was replaced by another British engineer, Edward Webb, whose first task was to look at ways of extending the line north from Petropolis; the awkward problem of what to do about the towering cliffs of the Serra do Mar was simply put to one side. It was difficult enough surveying on the top of the plateau, as Webb explains. His first problem came with local maps.

Maps there were in name, but they were worse than useless, because some reliance continued to be placed upon them, until their inaccuracy was proved. These maps are little better than itineraries depicted in lines; the distances upon them having been mainly determined, by the daily, or hourly progress of a saddle mule. A mule’s march per day, is reckoned at about a Brazilian league, or four miles per hour; and the distance between two places is marked by leagues, regulated by hours. If the roads were rectilinear and horizontal, such a calculation might approach to the truth; but as they bend in all directions, and at times, ascend gradients of 1 in 4, no true distance can be thus laid down on paper. On the same map, for example, an inch will represent at one part, a league, and at an another, two leagues, or more; positions of towns will be found interchanged, and rivers running in impossible directions. The Author was, therefore, obliged to discard these maps. All they are serviceable for is to point out a tolerably true line of coast, and to give the names of interior towns, rivers, mountains, &c, in the various provinces.

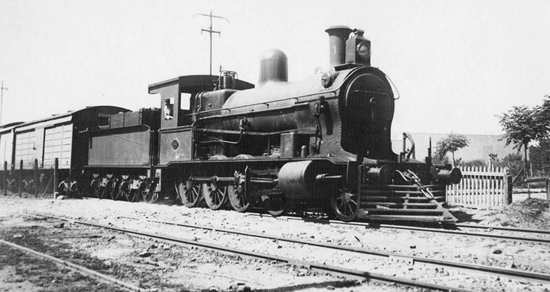

The first locomotive to work the Bahia-San Francisco line.

Then came the physical ardours of the survey itself.

Gangs of blacks were constantly employed in cutting paths, or headings, through the forests for the chain, theodolite, and level. It often happens, that to bring down one tree, six, or eight others must be felled, so closely do they grow together, and so firmly are their branches united, by ropes of wood. The surveying party lived in tents, and on no occasion desisted from work on account of the tropical rains, or heat. The survey and levels for the selection of a length of main line extending to thirty miles, were executed in four months and a half.

At the end of it all, the effort was wasted: the line was not built so Webb went on to finish the Manao Railway instead. This line offered few topographical difficulties other than one ‘deep, unhealthy swamp’; the difficulties that did appear were those caused by the lack of even the most basic equipment. Local Indians were disinclined to take up the work, and earned the scorn of the upright English engineer: ‘he plants a few banana trees, clears a small patch of ground for the mandioca root, or for the cultivation of black beans and rice, and all he cares for beyond, is to earn a trifle for clothes, rum, and tobacco.’ It was, needless to say, well beneath the dignity of any white man to work as a labourer, so the railway was built by slaves. The slave owners on the plantations were paid Is 4d a day for the use of ‘their’ men and women; the slaves themselves received approximately 7d a day’s worth of food. Webb’s only complaint about this system appears to be the high price.

Excavation along the line was carried out by the men, jerking the earth behind their backs with hoes, after which it was collected in baskets by women who carried it away on their heads. In dry weather it was more like dust than soil, and almost useless for building embankments; wet weather was so wet that virtually no work at all was done. Bridges were lightweight timber affairs, put together in a hurry to get the line open. Timber seems an obvious material to use in a country covered in dense forest, but it was that very density that caused the problems. Webb explains:

The Brazilian forests never present considerable areas covered with the same description of good timber, as in the pine forests; a serviceable tree generally stands in the midst of a group of various kinds of no actual value. The labour of dragging the squared balk from the place of its growth is almost inconceivable. A separate path for each piece of timber has, probably, to be cut, and the log has afterwards to be dragged, by bullocks, down precipices, over ravines, and through swamps.

Working conditions were far from ideal.

The district through which the line runs is very swampy, and it proved most unhealthy. All who were engaged in the works, sooner or later, were struck down by marsh fever. The heat, at times, was excessive; the temperature of the ballast, pure quartz, larger than sand and smaller than ordinary gravel, rose to upwards of 140°. Yet sickness in such situations seems attributable, as much to the impurity of the water consumed by the labourers, as to the excessive heat, or to the vitiated air. A supply of pure water to workmen, in similar positions, would repay a large expenditure for its carriage.

The cost of the 11-mile line, counting rolling stock, was about £15,500 per mile. In 1852 a 2-2-2 locomotive by Fairbairn of Manchester took Brazil into the railway age. The first part of the Maua Railway was complete.

There was no great rush into construction following the opening of the Maua Railway, but Baron Manua himself was now a dedicated enthusiast. He revived the idea of the Sao Paulo Railway and persuaded other Brazilians to join him in the enterprise. They offered a concession with a guaranteed return of 7 per cent on the £2 million capital and a promise that the line could be extended. It was in many ways an attractive proposition, in spite of the physical difficulties, for the line did serve a genuine commercial need: it linked the rich, coffee-growing area of the plateau to the coastal port. Once again, the obvious place to go to raise both finance and find expertise was Britain. Baron Manua had asked local engineers to survey the route, but they had only travelled as far as the edge of the plateau and had abandoned the whole idea. Now a new approach was made to the eminent British engineer James Brunlees who accepted the challenge. Like other leading engineers of the day, he could take on the consultancy without having to leave home, but he needed a trustworthy engineer to go out to Brazil for the survey. His choice was 26-year-old Daniel Fox who had some experience of the mountains having worked on a narrow gauge line in North Wales and done some surveying in the Pyrenees. He also spoke Spanish, which was considered a great advantage in Brazil – where the language is Portuguese! He accepted the job. It turned out to be even more arduous then Webb’s surveying work on the Manua.

Only those engineers who have made surveys through tropical forests can form a definite idea of the immense labour involved in the exploration and selection of a railway route in a country like Brazil, and especially on the precipitous and rugged sea face of the Serra do Mar. To add to the difficulties, the whole escarpment, from the deepest gorge to the loftiest peak, is covered with almost impenetrable primeval forests, through which the explorer has to drive narrow paths resembling ‘headings’. The exploring party usually remained in the jungle three weeks at a time, living in huts covered with the leaves of the palmetto, exposed to tropical rains and hardships of which it is difficult to convey an adequate idea, and emerging from the woods blanched from want of sunlight, which rarely penetrates the thick gloom of a Brazilian forest.

The greatest difficulty Fox faced was his inability to get a clear sighting of the whole escarpment. At the foot of the cliffs the trees obliterated much of the view and clambering up only showed a narrow portion. On one day he spotted what appeared to be a likely ravine, but at the end they were greeted by a glorious sight but no route for a railway. A high waterfall tumbled down a sheer face, and the energetic young engineer decided to scramble up the side for a closer look. His efforts were rewarded: he spotted the valley of the Rio Mugy, rising at a comparatively gentle angle up through the Serra. He had found his line, but his problems were only starting.

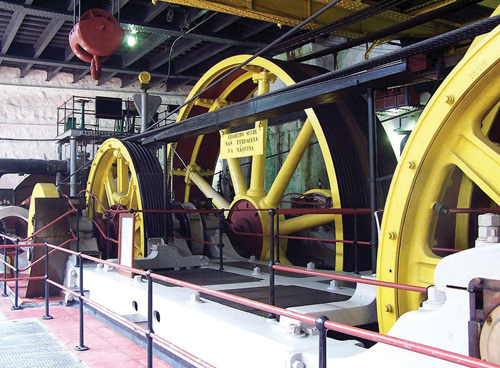

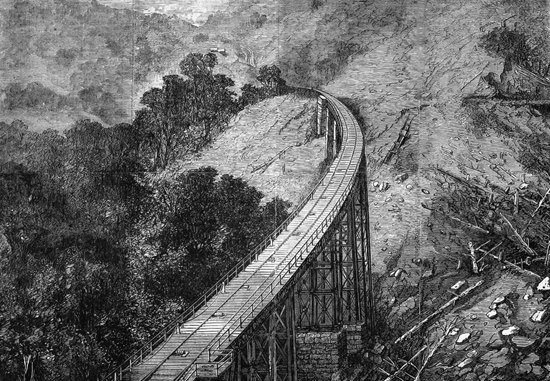

After fifteen months of surveying, Fox was convinced there was no alternative route up the escarpment, but he was still faced with a drop of over 2500 feet in just five miles, an impossible gradient for conventional traction of 1 in 10. Fox’s solution was a series of cable-worked inclines. There were four altogether, varying in length from 5842 to 7017 feet but these were by no means the only problems encountered along the way. From Sao Paulo, the line was continued inland to Jundiahy, 68 miles from the top of the inclines. Work here was no easier than it had been in the climb up the Serra. The land was sliced through with ravines, making necessary a long procession of banks, cuttings, viaducts and tunnels. The loose rock of the mountains revealed an unhappy tendency to slide back into the cuttings. The only solution available to cope with one land slip was to wash it away. A ‘considerable mountain stream’ was diverted into the cutting and a small army set to work, one part of which was kept busy shovelling the loose material carried down by the water, while the rest used the same spoil to build up flood banks. Gorges were spanned by lattice girder bridges, cuttings were in places almost a hundred feet deep, yet the contractors, Robert Sharpe & Sons, finished within budget and ahead of schedule. The Sao Paulo Railway remained as a British company well into the twentieth century.

A construction train in the San Ramino ravine on the Santiago to Valparaiso railway, for which William Lloyd was the engineer.

There was a general belief in South America, in the early days, that British involvement in a railway scheme was a sure-fire guarantee of success. Alas, this was not so. Farmers promoted the Dom Pedro – later the Central – Railway. They paid for the Warring Brothers to come from England to survey a route, but had enough good bucolic common-sense to turn down a system that included conquering the Serra using compressed air. In 1854, the Brazilian Embassy in London was authorized to find a contractor to build this problematic line, and they came up with the name of Edward Price. The brief was splendidly vague: it specified merely the gauge (5 ft. 3 in.) and the two termini. The rest was left to Price.

Their decision turned out to be a disaster. The contractor had no affection for expensive earthworks so the line swayed all over the countryside as if it had been laid down by an incorrigible drunk. The workmanship was atrocious. Station buildings were thrown together using the cheapest lath and plaster. Floors were of beaten earth, and not even well-beaten earth – one station waiting room had to be weeded every week to prevent it becoming totally overgrown. He added to the costs by bringing bricklayers from England, although there were perfectly competent workmen available in Brazil. His outstanding achievement was to set a line across a flood plain which disappeared under water every time there was heavy rainfall.

Happily not all lines undertaken by British engineers suffered the same low standards. The Bahia and San Francisco Railway was engineered by Vignoles, with his son Hutton Vignoles as resident engineer. It was a line on which the British had a controlling interest but the workforce was international: 446 Italians, 107 English, 11 Germans, 4 French, 2 Swiss and 2069 Brazilians. The international appeal of Brazil is not difficult to understand: the Brazilians had an enviable reputation for prompt payment of bills and honouring of commitments. When the government spoke of ‘guaranteed payments’, then they stuck to their word. Webb gave his views of the cosmopolitan workforce in typically blunt terms. The Chinese navvies, who began to appear in 1855, ‘were evidently the scum of the population; utterly useless as labourers, they proved a continual source of annoyance and loss, and not one in ten was worth his food.’ The Portuguese labourers, on the other hand, were first rate, if a little conservative: they arrived already organized into gangs headed by sub-contractors.

Each of these men brought with him from sixteen to sixty of his countrymen, and the gangs, thus formed, dotted the line of the works with their triangular huts roofed with grass.

The Portuguese labourers are a very hardy race of men, who can endure greater privation and exposure than English labourers. At first, they refused to use the barrow and the shovel; the hoe, their only tool, was not, however, so objectionable along the steep sides of the Mangaratiba mountains, as it was on the plains of Manua; and in certain localities, from its acting as pick and shovel combined, it was even the best tool that could have been used.

The railways first executed in Brazil all had this international element as did those in other parts of South America as far as construction was concerned, but the British continued to own some lines, right through into the twentieth century. Cash spoke louder than the rival claims of local interest, multinational labour forces or old imperial allegiances. Lines throughout South America had an equally strong English accent.

While Brazil was establishing its rail network in the 1850s, neighbouring Argentina scarcely existed as a modern nation-state at all. Large areas were either self governing or scarcely governed at all. There was no rush into railway building largely because no one saw any need for railways: there was no manufacturing industry, no mineral wealth. A few far-sighted individuals did see, however, that railways could play an important political role in pulling the disparate elements of the country together. The group of provinces in the interior, the Argentine Confederation, was a potential nucleus for a unified country, and in 1853, the Confederation spokesman Juan Alberdi spelt it out in the simplest terms: ‘railways will bring about the unity of the Argentine Republic better than any number of congresses.’ In 1854 the Confederation engaged an American engineer – on the not always sound ground that he was the cheapest available – to survey a line from Cordoba to Rosario. There was then the problem of finding the cash, and the Argentinians approached another American, William Wainwright, to organize the fund-raising. He in turn approached the powerful corpus of British merchants based in Buenos Aires but they had nowhere near enough capital themselves, nor could they raise funds in London where the effects of the Crimean War were being felt. The plans were set aside, but the idea of railways out of Buenos Aires had nonetheless grabbed the imagination of the British merchants.

If grandiose schemes had to be temporarily shelved, a more modest beginning was possible. Daniel Gowland, chairman of the British Merchants committee in Buenos Aires, was one of the most enthusiastic supporters of the Ferrocarril al Oeste, the Western Railway. The local government gave the necessary official support: the building land was free, the capital equipment brought from overseas was exempt from customs duty and they put up a third of the money, but agreed not to take any dividends until private investors were receiving 9 per cent. The arrangements sound as if they were designed to finance an entire rail network, but it was, in fact, no more than a modest suburban line which built up over the years to a less than impressive 25 miles of track. Yet the locals still found it necessary to send to Britain for William Bragge, who came across with 160 navvies in tow. In due time rolling stock and locomotives were sent from England, and to show that the little suburban railway was in reality destined to be part of an altogether vaster enterprise the engines were given stirringly heroic names: Progreso and Luz del Desierto (Light of the Desert). The line was built to a broad, 5ft. 6in. gauge as were lines already begun in Brazil and Paraguay. This decision was attacked by Argentinian patriots who declared that the gauge had been set not out of any rational drive to link up with neighbouring railways, but because secondhand rolling stock from the Crimea was beginning to come on to the market.

The 1000 horse power steam engine powered winding system at the top of one of the inclines on the São Paulo Railway

A Locobreque that can be translated as brake locomotive on one of the inclines

The Serra viaduct on the São Paulo Railway

In May 1862 General Bartolome Mitre became President of Argentina, and the previously independent province of Buenos Aires came, if only partly, under the control of the new national government. There now began a period of western-style economic expansion which coincided with the new legislation in Britain that gave joint-stock companies their legal basis. It was a happy conjunction: Argentina wanted money for investment, Britain had the cash looking for a profitable home. And the Argentinian schemes were potentially very profitable indeed, with government guaranteed returns and handsome land grants. The cynical might say that the taxpayers of South America were being forced to hand out expensive sweeteners to the wealthy investors of Britain; defenders of the scheme would ask how else railways were ever to be built. Whatever the morality of the scheme, it certainly attracted funds. By 1875 over £23 million had been invested in Argentina of which nearly a third went on railway construction.

The impetus for railway building came, as it had in Brazil, very largely from the British merchants who had set up in business there. The leading figure was G.W. Drabble who had first come to Buenos Aires in 1842 as representative of the family’s cotton-exporting firm based in Manchester. He stayed on and eventually became Chairman of the Bank of London and River Plate and the principal promoter of the Central Argentine Railway. However assiduously local interests promoted the line, however, there was no disguising the fact that they were a good deal less enthusiastic about paying for it. The largest sum, invested by the richest family in the country, was £200 which contrasts with the £20,000 invested by a Mrs Sanders of whom nothing very much is known except that she lived in Derbyshire. Not surprisingly those most closely involved in construction were the major investors. On the Buenos Ayres Great Southern, the engineer who took the first contract, Thomas Rumball, was a heavy subscriber, as were the contractors, Brassey and Wythes, Peto and Betts. They acted wisely, for the success of the line ensured an excellent return. At the opposite extreme, financially as well as geographically, was the Northern Railway of Buenos Ayres (sic). It was promoted in England by E.H.S. Crawford MP and was to run from Buenos Aires to the Rio Maldonado at San Fernando where a new deep-water port was to be constructed. It was from the first a story of muddle and incompetence. When the line was open there seemed to be no shortage of passengers, but receipts were depressingly low. It was only when someone was sent to investigate that it was discovered that local railway employees were taking out sheaths of tickets and selling them from a booth outside the station at a third of the regular price.

Everyone expected to get something out of the railways. The government had fine phrases for each new opening ceremony. When Mitre took the ceremonial spade to inaugurate work on the Central in 1863, he declared that ‘Everyone must rejoice on the opening of this road, for it will tend to give riches where there is poverty and to institute order where there is anarchy.’ The railway would, the government hoped, encourage settlement along the route as the lines struck out into the open plains of the pampas, hence the land grants. It was a point not lost on speculators. They could buy land on the cheap and as the railway approached, sell on at great profit. The sharper practitioners realized that they did not even have to do that. They could buy up land, announce that they were promoting a railway over it, sell the land – and forget all about the railway. Mitre at least managed to stop this particular scam by announcing that the government would decide where railways were to be built, leaving it to private capital to finance them.

There was something of a confrontation between the British entrepreneurs and the American interests led by William Wheelwright. In 1862 Wheelwright finally got the concession to build the Central, the line he first proposed from Cordoba to Rosario. At the same time, the British group led by Edward Lumb was authorized to build the Great Southern from Buenos Aires to Chascomus. There were tax exemptions, land grants and guaranteed returns for both parties. The British got the more favourable guarantee, at a return of 7 per cent on a capital investment set at £10,000 per mile; Wheelwright, for his part, received a more generous land grant. He decided, however, that cash in hand was a better bargain than land and objected to the terms offered to the British interest. Lumb’s group won, not because they necessarily had a better case, but because they were more generous in their dishing out of bribes. It was estimated that they paid £22,000 to various officials. Work on the Great Southern got under way and an interesting array of speculators, engineers and contractors descended on the country. There was no question but that they did well out of it. Where locals used paper money issued by local banks – the bank of Cordoba, for example, circulated 33 million pesetas in notes, while holding 8 million in gold – the railway men got their cash in gold. The government kept handing out reserves, hoping one day it would come back in investment. Eventually the tail did manage to catch up with the dog.

The railway builders had a different view to the speculators: they saw themselves as public benefactors helping a backward country to achieve its rich potential. Helps in his biography of Brassey wrote, ‘I think that this Argentine enterprise of Mr Brassey’s will have more important results than any other of his undertakings’, and again, ‘I doubt whether, in the history of railway enterprise, there has been anything so largely beneficial to the country wherein a railway has been introduced.’ The contractors were not merely railway builders, that was the easy part. Indeed, the going was so easy for much of the way that all the navvies had to do was lay the sleepers on bare earth and spike the rails to them. These contractors were also colonisers, opening up the country, encouraging immigrants to settle. The railways themselves created a demand as the British Charge d’Affaires reported in 1866: ‘The supply falls very short of the demand, and unlimited employment can be procured without difficulty at most remunerative wages, as in this country artisans and labourers are greatly needed.’ Railway workers flooded in, mainly from Spain and Italy, with a few from Britain. They mostly took their wages, finished the job and went home again. Railway empire building did not go quite as planned: the men came as migrant workers, not as settlers. Nevertheless, until Peron took over all the railways in the country, the British had built and still owned some 16,000 miles of track in Argentina. They were never to dominate any other South American country to the same extent; for most of the rest of the region the dominant figure was supplied by the USA in the form of the swashbuckling contractor Henry Meiggs. That does not mean that the British did not make significant contributions to the work elsewhere. In 1865, for example, the Central Uruguay Railway was promoted using a guarantee that began at 7 per cent and when it was increased to 8 per cent on capital set at £10,000 per mile English contractors stepped in; it was the Argentine story all over again. When the line opened, much of the rolling stock and most of the locomotives were from England – specially-built components from Robert Stephenson, engines from such well-known companies as Beyer Peacock, Manning Wardle and Vulcan. More challenging situations appeared further south.

Beyer Peacock 4-6-0 with a train of cattle trucks on the Buenos Aires Great Southern Railway in Argentina in the 1920s