The crest was designed to show the value of railways: contrasting the bearers struggling with a palanquin with the steam locomotive and its train of carriages

Early railway building in Asia was inseparably entwined with the process of colonization. Britain had not set out to acquire an Asian empire, but had more or less stumbled into it by the early nineteenth century. At its heart was the vast territory of India. It is not possible to understand the complexities of railway building here without first having at least a notion of the underlying political situation. Even the name ‘India’ has meant different things to different people at different times; it has never been prudent to anticipate a long shelf-life for a map of India.

The British had very little interest in the Indian sub-continent during the early years of exploration and colonization. When Elizabeth I granted a royal charter bestowing trading rights in Asia, it went to the East India Company. The name is significant: the objective was the spice islands of the East Indies but unfortunately the Dutch had got there first and established territorial rights and a trading monopoly. They were also strong enough to defend their position. The British looked instead to India. That country was already carved up into areas of influence. Much of the land was ruled by the Moghuls who had migrated south from Persia early in the sixteenth century. The early British traders must have been overwhelmed by the capital Agra, with its opulent temples and palaces behind massive fortress walls. And by 1632 they could have looked downriver to where that most famous of all Indian palaces was being built, the Taj Mahal. But already the Moghul Empire was beginning to slide and disintegrate and two European powers, France and Portugal, had important enclaves. There was plenty of room still for the British to shoulder their way in and join in the wholesale exploitation of the country. International rivalries were inevitable: the native princes quarrelled with each other, and France and Britain were soon at war. The Seven Years War began in Europe but spread to India, and the British victory signalled an end to French involvement in the sub-continent. The Portuguese were more concerned with religious introspection than trade, and they were left to their tiny enclave of Goa. By the end of the eighteenth century, the most effective force in India was neither the government nor the princes, but the privately run trading empire of the East India Company. In 1765 Robert Clive, commander of the British forces, formally accepted the state revenue of Bengal, making that state, in effect, a colony – and one that was to be stripped of its assets with no thought for the future. The age of the nabobs had arrived, the men who went out to India, nominally to serve Britain, in practice to serve themselves and come home flaunting huge wealth. It was all very well being flamboyant in India, but in Britain it caused deep resentment and envy. The government acted. There was now to be a division between trade and administration, and the two should never again mingle. No administrator could ever again legally use his public office for private profit. It was a difficult and confused time: India, or a large part of it, was effectively under British rule, but relations with the British Parliament were distant. The Governor General could – and did – overrule his Council. There was an excellent Civil Service – the best paid anywhere in the world – and two armies, one owing allegiance to the Crown, the other to the East India Company. It all made for complexity, and complexity does not make for decisive rapid action, as the early railway promoters were to discover.

The crest was designed to show the value of railways: contrasting the bearers struggling with a palanquin with the steam locomotive and its train of carriages

The case for railways was easily made. Trade with Britain meant that communication and transport had taken on a new importance; and the current state of the roads was atrocious. It is always difficult to assess accounts of bad transport systems of a century and a half ago, but in the case of India one can at least use the yardstick of the modern road system. Most would come to the conclusion that if this is what the roads are like at the end of the twentieth century, they must have been truly appalling 200 years ago. Even today, traffic is dominated by the lumbering cart drawn by bullock or camel or by pack animals. An engineer visiting India while the railways were first being planned wrote,

Indian railways will not, therefore, as in England, be the substitution of a perfect system of conveyance for other convenient means, at the demand of a prosperous nation; but they will be, at least in many districts, the first introduction of any communication whatever.

A civil servant described a twelve-hour journey which involved seven hours of bone-rattling travel over a dirt track masquerading as a main road: ‘On his way the manslutdar amused us with several stories of accidents which had occurred on this road, one of which related to the sad fate of a banion, or trader, who received such a jolt as to make him inadvertently bite the end of his tongue off.’ There were, however, more pressing needs for transport improvement than to improve the travel conditions for junior civil servants. India was attempting to build up a prosperous cotton exporting industry. Mr Mangle, one time Chairman of the East India Company, had no doubts about what was holding back the process: ‘I have made the largest admissions with reference to the want of roads, which I say, is the only real obstacle to the exportation of cotton in large quantities from India.’ Other powerful interests found the lack of efficient transport a severe hindrance. Sir William Andrews put the military point of view and quoted a telling example:

In 1845, when the First Sikh War broke out, all officers, whose regiments were in the field, were ordered to join the army. About 100 engineer, cavalry and infantry officers were required to go from Calcutta to the north-west frontier of India. They were sent at the public expense, and with the greatest despatch, but the Postmaster-General could only send three daily! As the journey took 16 days, travelling day and night, few of these officers rejoined their regiments before the war was over.

This could, of course, be taken as an argument that armies manage perfectly well without their officers, but it also reinforces the point that no one in British India was happy with the old transport system inherited from the Moghuls. The army were to become builders of railways on their own account, though some of the officers seem to have been afflicted by decidedly wild notions. One military engineer, Lieutenant Colonel John Kennedy, began his proposals for construction with a full-scale tirade in which he ‘condemned heartily and completely, all that railway engineers had accomplished in England.’ One of his fellow officers, Lieutenant Colonel L.W. Grant, was so worried about the threat from wild animals, that he proposed hanging an entire railway from chains; the resulting track was eight feet above the ground, like a vastly elongated suspension bridge. Happily, other military engineers had rather more practical, and conventional, schemes to put forward.

The main impetus for railway construction, however, came from the civil section of Indian life – indeed the beginnings can be put down largely to one enthusiastic individual, Rowland Macdonald Stephenson. His ambitions, according to a piece in the Calcutta Review in 1856, were large. He wanted ‘to girdle the world with an iron chain, to connect Europe and Asia from the furthest extremities by one colossal Railway … to connect so much of the two continents as should enable a locomotive to travel from Calcutta to London with but two breaks, one at the Straits [Dover] and one at the Dardanelles.’ His early proposals had a more limited end: to see a line built that would join Calcutta, then the capital, to Delhi. Stephenson had the advantage of a sound background in civil engineering and a long family connection with India. An ancestor had negotiated a treaty on behalf of the East India Company, and other members of the family had kept up the tradition. Only his father had let the side down, absconding from the firm in which he was a partner and taking the company cash box with him. Perhaps Stephenson’s enthusiasm for public works stemmed from a desire to restore the family honour. He himself worked for a while for the East Indian Steam Navigation Company which lost out to the Peninsular and Oriental (P&O). When in 1841 he began his propaganda war, his background and experience ensured that he was given a hearing, but it was not until 1844 that he gained a positive response. He wrote to the government of Bengal and received an encouraging reply: he had found a supporter in the important figure of the Deputy Governor. The Secretary to the government wrote, ‘The Deputy Governor desires me to add that he is deeply sensible of the advantages to be gained by construction of Rail Roads along the principal lines of communication throughout the country, and is anxious to afford to any well-considered project for that purpose his utmost support.’ And to make clear that this was not a casually issued offer of help, the Deputy Governor published his reply in the Calcutta Gazette.

Armed with the goodwill of the government and with the backing of local merchants, Stephenson set off to promote his line, now christened the East India Railway, in the money markets of London. British investors had never shown themselves particularly keen to put their cash into schemes in distant India and they were no more enthusiastic about railways. They would only invest if the government put up cash as well. This was not very encouraging, and Stephenson went on to approach the Court, the ruling body of the East India Company, with a good deal more trepidation than he had shown when contacting the government of Bengal. He suggested that they should offer to guarantee a comparatively modest return of 4 per cent on capital, but even this was more than the Company was prepared to offer. They came up with an array of reasons why the railways would not work: the country was poor, no one could afford to travel, and there would not be enough freight traffic to make good the difference. Could they get competent engineers? Would beetles attack the wooden sleepers? Would track be washed away in the monsoon? The list of obstacles seemed so long that it must have come as a pleasant surprise to Stephenson that the East India Company ended up offering anything at all. In the end, however, it offered to pay for a survey.

The first running of a train on the Bombay to Thana line

In 1845 F.W. Simms set out for India to begin the work. He turned out to be just the man the Company did not want for the job: instead of confirming their wholly negative views, he proved an enthusiast capable of out-enthusing Stephenson himself. After covering the ground with two military engineers as companions, he declared that there was no reason at all why railways could not be built in India and furthermore young Indians could be trained to run them. He wholly approved Stephenson’s 900-mile proposed route and put up a case for the whole line being built and operated by a single company. The Under Secretary for the government was only one of many in India who had doubts about funding.

Is it possible that England will send to India the enormous sums which may be required? Other countries have effected works of great magnitude out of their own wealth, but India must look to England for the necessary capital. She must ask back a portion of the tribute which for years past she has paid to England.

This pessimism was not unwarranted. Company and government could not agree on how railways were to be built, where they were to be built or how they were to be paid for. Meanwhile other schemes were coming forward.

In 1844, the Bombay Great Eastern Railway was formed with the intention of building a 53½-mile route from Bombay to the Western Ghats, the line of cliffs over 300 miles long that rises up over a thousand feet from the coastal plain of western India – presenting just the sort of barrier that had faced the engineers working in South America. It looked on paper to be a thoroughly sound venture backed by an array of worthies, ranging from Sir Bartle Frere, Private Secretary to the Governor, to minor government officials, British traders and merchants, and leaders of the Indian mercantile community. The promoters had taken advice from a friend of Frere’s, the engineer George T. Clark who had come to India in 1842. The government committee set up to study the prospectus was not, however, greatly impressed. The costs were, they declared, pure guesswork since there had been no survey and the route had not been studied ‘by any party whose evidence, written or verbal, we had the opportunity of obtaining’. If the scrutinisers were dubious about the costs, that was as nothing compared with the scorn with which they treated the estimates of revenue. The promoters had boldly prophesied a return of 22½ per cent; the committee came up with a figure of one eighth of one per cent – though they conceded that with an improved plan, a modest 4¾ per cent might just be attainable. This was all very discouraging, but now a new contender appeared on the field with an even more ambitious scheme. John Chapman was an engineer recently arrived from England, but he identified a genuine need that only a railway could meet. His Great Indian Railway would unite the cotton fields of the interior with the Port of Bombay. His idea could hardly have come at a better time. In 1846 the cotton crop of America failed and the mills of Lancashire were starved of raw material. They looked to India to fill the gap.

So it was that in the mid-1840s, two railway systems were being promoted, each of which promised tangible advantages to British interests. In the east, a railway could bring coal to the port of Calcutta, a vast advantage to the burgeoning steamship lines. In the west, the other route would feed the seemingly insatiable demands of the cotton mills. Real progress seemed possible, but still the East India Company dithered and wavered. However clear the matters might seem to engineers like Simms who had surveyed the land or to the merchants on the spot who understood the needs of local markets, the men in London who had ultimate control were not convinced. But there was leverage that could be applied. The East India Company charter was shortly coming up for renewal, and although the British government was not directly involved in the railway question, it was very much in control of that charter. Impassioned pleas came out of India. An anonymous pamphlet addressed to Lord John Russell was a patchwork of purple prose:

England, the Lilliputian island, rich and selfish as a pampered glutton, has indulged to excess in the luxury of Railways. Let her now resign herself to repose and the needful process of digestion, while her slave, the giant continent of India, feeble from inanition and sick at heart from hope deferred, is permitted to break her fast upon the superfluity of her master’s abundance.

The East India Company gave way under the pressure, and agreed first to a 3 per cent and then – when that was shown to be too meagre to attract much in the way of funds – a more generous 5 per cent guarantee. The East Indian Railway Company and the Great Indian Peninsula Railway were given the green light – or perhaps more accurately the amber. Each was authorized to build a comparatively short length of track: from Calcutta to Raneegunge, 120 miles of the originally planned 900 miles in the former case; and Bombay to Kalyan, just 30 miles, in the latter. The agreements contained some clauses which were incredibly generous to the infant railway companies. If the railways made a loss, the East India Company would take them over and repay all the money that had been spent. Having ceded so much, the East India Company tried to protect their investment by exercising control over just about everything. The arrangements read like a recipe for chaos. There were to be two engineers in charge, one appointed by the railway company, one by the government. The railway engineer would create a design or a plan which was then passed to the consulting engineer for approval. If the latter agreed, all well and good. If not the matter was referred to the Indian government, and any arguments there were sent to the government in London for final arbitration. No one, it seems, thought it remotely odd that, for example, the siting of a signal box on the dusty plains of India should ultimately be decided by a solemn conference of Members of Parliament, whose previous experience of railways had been limited to journeys on the London to Brighton line.

Fortunately there were saner voices to be heard in the land. If there was more than a touch of the ludicrous in the deliberation of the supposedly practical men who devised the system of railway construction in India, there is an equally absurd touch to the fact that these good commercial men had to be rescued by Sir James Andrew Brown Ramsey, first Marquess and tenth Earl of Dalhousie, who was appointed Governor General of India in 1847 at the age of thirty-five. He was, at least, aware of the problems presented by a rapidly expanding rail system for he had been Vice-President of the Board of Trade in the Peel administration during the boom years of the 1840s. He was a short, stocky man who managed to combine aristocratic hauteur with bustling energy and a fierce temper. He was an aristocrat by temperament, a man who never for a moment doubted his right as well as his ability to lay down the law for others. He did not suffer fools gladly – nor indeed did he suffer them at all. A splendid example of Dalhousie at work came when he was asked to arbitrate on the experimental line from Calcutta. Around £1 million had been allocated to the East Indian Railway to build a double track to the mines of Raneegunge. For that sum Simms, the company engineer, had calculated that he could either build a single track all the way or a double track that would come to a halt in the middle of nowhere, thirty miles from the mines that were to supply the traffic. The answer might seem obvious, but voices were raised demanding the letter of the law be adhered to and double track must be laid. Dalhousie demolished that argument:

Bombay would eventually get the grand Victoria terminus: now the Chhaptrapa Shivaji, Mumbai.

If the experimental section be constructed in literal conformity with the orders of the Court, of a double line and only so as not to compromise the Government in the slightest degree … I conceive that this section, commercially, must be a total failure. If the object … is to prove the practicability of forming a railway as a public work, the fact could be proved on a quarter of the distance and at a quarter of the expenses. If, as I have assumed, the object in view is to prove the profitableness as well as the practicability of a railway in India, I regard this proposal as totally useless. The Government might as well contract a railway from the Gaol to the General Hospital.

The line was built single track, with space left for a second line to be added at a later date.

Dalhousie’s main achievement was to bring rationality and order to railway planning. He had seen at first hand the problems caused in England where Stephenson’s standard 4 ft. 8½ inch gauge clashed with Brunel’s 7 ft. broad gauge. India was starting with a clean slate: there were no other railways with which connections had to be made, so that a rational decision could be taken and an ‘ideal’ gauge settled on. Dalhousie put his own views on gauge differences in typically forthright terms: ‘The Government of India has in its power, and no doubt will carefully provide that, however widely the railway system may be extended in this Empire in the time to come these great evils should be averted.’ So they were, but in less than two decades the pattern was broken. Economy became the new criterion, and the gauge shrank from Dalhousie’s proud broad gauge, down past the Stephenson standard, to just one metre. Later these would be joined by an assortment of narrow gauge routes tackling the difficulties of the mountains. But, for a time at least, rationality ruled. Dalhousie’s other great contribution was to appoint a Consulting Engineer for Railways in 1850 who was able to take an overall view and lay down sensible rules for development.

Colonel J.P. Kennedy, that fierce denouncer of the piecemeal development of lines in England, established criteria for route selection which never lost sight of the main aim of providing a network of railways that would meet the needs of the whole country. Under Kennedy’s guidelines, no one railway was ever considered in isolation but always as part of a greater whole. He made sure that absurd quarrels like that over the East Indian Railway should not recur by laying down that although lines could be built as single track, all earthworks, bridges, tunnels and so forth should be capable of taking a double track. He also set down that the maximum cost per mile of single track should be set at £5000. This was, to say the least, somewhat optimistic. In Britain, up to 1858, the average cost was nearly £35,000 a mile, ranging from £38,000 in England to £115,000 in Ireland. It was estimated that a quarter of that was taken up with the expenses of obtaining an Act and buying land, neither of which was applicable in India, and taking those out of the equation reduces the cost to roughly £26,000. Then again some two thirds of the mileage was double track but even if one makes the very dubious assumption that double track costs twice as much as single, that still produces a figure in excess of £15,000 a mile, or three times Kennedy’s allowance. In the event, Kennedy’s figure was never achieved, though the Madras Railway did manage to build much of its track at a cost of only £7000 per mile. But the importance of Kennedy’s work lay in the fact that standards were set: railway builders knew how matters stood, and on what basis they were expected to operate. Work on the two experimental lines went ahead.

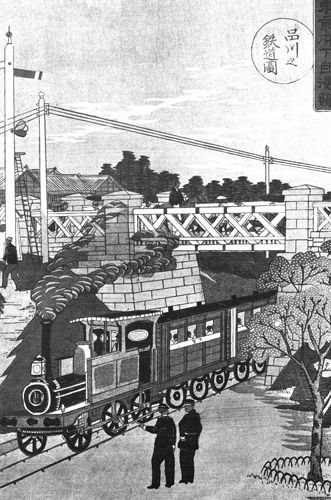

In 1853 an event occurred which the Overland Telegraph and Carrier described as ‘a triumph, to which in comparison all our victories in the east seem tame and commonplace’. It would, the anonymous enthusiast wrote, ‘be remembered by the natives of India when the battlefields of Plassey, Assaye, Meanee and Goojerat have been forgotten’. This was the fact that twenty miles of the Great Indian Railway were opened from Bombay to Thana. Not everyone seemed equally aware of the historic nature of the occasion. It was the habit of the British at the approach of summer to leave the sticky heat of the plain for the comparative cool of the hills. They were not about to change their habits for anything as mundane as the opening of India’s first railway. The Governor of Bombay, the Commander-in-Chief and the Bishop of Bombay left for the hills just hours before the ceremony. Was it a deliberate snub? It seems unlikely that it could have been a mere coincidence. The official absence did nothing to dampen the celebrations, as 400 passengers left the Bori Bunde station in Bombay to the accompaniment of a 21-gun salute, the sounding brass of the Governor’s band and the cheers of the crowd.

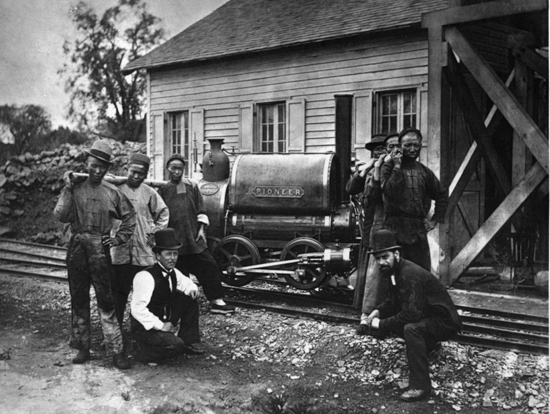

Progress on the eastern line inevitably took longer, and there were some unexpected delays. There was a political row with the French, who still ruled a small parcel of land which they claimed lay directly across the line. For their part the British declared the route was nowhere near any French territory. This was little more than an irritation: the French were in no position to push any claims in India. By 1853 the line had reached Pundooah, 38 miles from Calcutta. All that was needed for a grand inauguration ceremony was a train: unfortunately, a train was just what they did not have. ‘Pattern carriages’ had been sent over from England, but the ship carrying them sank in the mouth of the Hooghly River. John Hodgson, the Locomotive Chief Engineer, was not unduly concerned. He designed his own carriages and had them manufactured locally. The first locomotives were ordered from Kitson Thompson and Hewitson of Leeds. They were handsome 2-2-2 Well Tank locomotives, with shiny high domes and tall chimneys: one of the class, the Fairy Queen of 1855, has pride of place in the New Delhi railway museum. The first engines, however, were delayed, partly because they were shipped out on a bizarrely long route via Australia. As a result the first train only ran in June 1854. The great opening ceremony, in the presence of Dalhousie, took place in 1855 when the whole line was open to Raneegunge. It was not strictly true to say that the line ran from Calcutta. Howrah station, a makeshift affair of huts and sheds, stood across the wide Hooghly river, and passengers from Calcutta had to take a ferry to reach it. Many years were to pass before the river was bridged and the lines reached the city itself.

Lahore station looks like a medieval fortress and was indeed designed with defence in mind

The experimental railways were an undoubted success and confounded the experts by at once attracting a busy passenger trade. One other line was begun in Madras in Southern India, which opened its first section with equal success in 1856. Railway building, however, was overshadowed and temporarily obliterated by events. The forceful Dalhousie left India in 1856 and his place was taken by the more thoughtful and deliberate Lord Canning, son of a more famous father. Within a year there was a general uprising through most of northern India against British rule, which Indian historians refer to as the War of Independence and which the British of the time gave the equally untrue title of the Mutiny. It was unquestionably a major conflict, which caught up a number of hapless railway builders in its violence.

The opening of a new line in India was always a grand event: the garlanded locomotive is on the Ulwar’ Rajputana State Railway, the country’s first metre gauge line

Those sections of railway that had been built, notably the steadily expanding East India line, the route between Agra and Delhi and that between Allahabad and Cawnpore, were used by troops, but elsewhere construction sites were attacked and half-completed lines ripped up. The civilian engineers were inevitably drawn into the conflict: some died and those who survived usually joined one of the volunteer forces. The engineers working in small groups far from home base were most at risk: one group only escaped with their lives by hiding out in a newly completed water tower. Some of the most dramatic events occurred in the little town of Arrah between Allahabad and Patna. This was a section of the East India line, but isolated from the railhead which was still stuck at Raneegunge. The engineer in charge, Richard Vicars Boyle, had earlier had a number of skirmishes with local tribesmen, and the tensions that were to build up to the great explosion of the Mutiny itself were already being felt. A small group of engineering staff and their families lived in a European enclave, and long before serious trouble broke out, Boyle arranged for all the wives and children to be sent to the comparative safety of Dinapore, nearly 30 miles away down the line. At the same time he asked for armed protection and the District Magistrate sent a detachment of fifty Sikh police to Arrah.

Boyle was meanwhile making his own arrangements for defence. A small building in the garden, surrounded by a colonnade, was used in more peaceful times as a billiard room. Now Boyle bricked in the arches to create a miniature fort which was ready by mid-July 1857 when the 2500 sepoys at Dinapore rose up and joined the Mutiny. Within two days they descended on Arrah, where they broke into the gaol and raided the treasury before turning their attention to Boyle and his tiny force. They had a small amount of artillery in the form of two light guns, one of which was hauled up to the roof of Boyle’s house from where they began firing at the little fortress in the garden. They kept up the bombardment for seven days, during which a relief force was ambushed and routed with heavy casualties. A second relief column under Major Eyre was more circumspect, rounded the flank of the mutineers and scattered them. Boyle and his men survived, and only one of the Sikhs had serious injuries. The incident had no affect on Boyle’s career: he stayed on in India building railways until 1864.

The Mutiny was bloody but short. There was one lasting effect: it marked the end of rule by the East India Company. The change of government had no marked affect on everyday affairs and life, including railway building, gradually went back to normal. There was, however, a new impetus given to construction: if the Mutiny did nothing else it proved the importance of good communications in a vast country. There were also more lasting memorials. New stations became potential fortresses. They all but enclosed the tracks, so that trains could be protected inside. The face these stations presented to the outside world was grim: high walls, rounded corners that would deflect shot, battlemented towers and firing slits. The grander stations, such as Lahore, looked more like medieval castles than places to purchase tickets. But the station-fortresses were not needed. Railway engineers found themselves facing different enemies: a fierce landscape, extremes of weather and the ravages of disease. Contractors also faced their own special problem: prices that had been negotiated before the Mutiny began to look distinctly less appealing afterwards. Among those who came to India was Thomas Brassey who formed a new partnership of Brassey and Wythes for the occasion, and ended up losing money. There was hence an understandable nervousness among European staff in the aftermath of war.

In 1856 John Brunton was appointed chief engineer for the Scinde Railway that was planned to join Karachi to the East Indian Railway at Delhi. The only advice he was given as he left England was to drink soda instead of the local water. It was not a comfortable journey: first by boat to Alexandria, then by camel train to the Red Sea, and on by boat again. The book which he wrote, he said, to amuse his grandchildren, contains accounts of such merry events along the way as the chasing of a giant rat which he killed with his bare hands – of such stuff were Empire Builders made. He arrived at Karachi just as the Mutiny was ending and set about organizing a trip to view the proposed route, or to be more precise he got his Goan butler to organize the trip, since at this stage of his career Brunton had no local languages. He and his staff set off on camels, camping along the way with the aid of twelve tent-pitchers. It was the tent pitchers who set the pace, for they travelled on foot carrying all the gear. Progress was a modest ten miles a day. Brunton armed himself with a brace of pistols and a sword, but they were only needed once, not against rebellious Indians but against a rabid wolf that attacked a village where they were resting. Five days out, there was an alarming report that the mutiny had broken out again in Karachi. Brunton had left his wife there, and he at once grabbed a camel and galloped through the night on the 56-mile journey back. The rumour was false, Karachi was calm. He returned to the survey party at a more sedate pace.

Confidence grew that the peace would last, though there was no shortage of problems to keep Brunton busy. On the whole work proceeded smoothly, with the line divided into sections, each under the control of an assistant engineer. Actual construction was limited to the winter months: in the heat of summer they caught up on drawing plans and sections. It was still received wisdom that work should be let to British contractors, even if those contractors chose to use native labour. One contractor named Bray aroused suspicion from the start. ‘I and my staff, wrote Brunton, ‘had much to do in watching these proceedings and trying to keep Bray right.’ They were not vigilant enough: Bray absconded taking his funds with him, and leaving the men unpaid. They were ‘a very rough lot’ from Central Asia and rioting broke out, not surprisingly since the men were half-starved. Brunton seized all the plant and equipment, persuaded the government to pay the wages bill and decided that in future he could do without the services of a contractor. They worked a piece-rate or a day-rate system and gave no more trouble.

Health was a perpetual problem for most Europeans in India. One particular spot, Darbaji, had been chosen as a site for a station, but no one seemed able to work there for any length of time without falling ill. Brunton asked a native to show him where the drinking water came from: ‘He took me about ½ a mile into the Jungle and showed me a small pond of water, covered with green slime and filth – for the Buffaloes & other animals grazing in the Jungles came here to drink.’ He carried out a simple geological survey, sank a well and the problem was solved.

His later career was certainly varied. After the Scinde line was completed a new one was proposed along the Indus valley, to complete the link from Karachi to Multan and the Punjab and Delhi Railway. To some extent, his work was much like that of other engineers surveying in India. He set off with a retinue of thirty-five servants and tent-pitchers, and an escort of fifty cavalry and fifty infantry. One problem Brunton faced was finding suitable stone for ballast, but he had heard of the great ruined city of Brahminabad in the Scinde desert and set out to hunt for it. He found it – surrounded by walls 20 feet thick and 14 feet high: all the ballast an engineer could want provided he had no thoughts for archaeology. During this period, in order to make life more tolerable in Karachi, he ordered 800 tons of ice from the Wenham Lake Ice Company – who sent it to Bombay by mistake. So Brunton bought refrigeration equipment and made his own. Encouraged by this success he then began manufacturing soda water!

Fairy Queen, built by Kitson in 1855 for the East Indian Railway, is now preserved in the railway museum in Delhi.

When the survey was completed he was called back to England to give evidence in the case of Bray, the absconding contractor – a case that was to drag on for two years. Brunton did not wait for the result but returned to the Indus. In an account which he wrote for the Institution of Civil Engineers, Brunton expressed his opinion of Bray with a dry humour:

Without entering into a statement of the causes of Messrs. Bray’s relinquishing the works, which at present form a subject of legal reference, it will suffice to say, that when the Company’s Engineers took possession of them, they had to encounter difficulties which were not due entirely to the peculiarities of the country.

As work progressed, the company decided to provide an alternative form of transport, and Brunton found himself with a new job in charge of steamship operations between Kotri, near Hyderabad, and Multan. The steamer was sent out in sections and assembled on the spot, but had difficulty coping with the swift Indus current. It struggled upstream to make the 700-mile journey in thirty-four days; then turned round and shot downstream in a week.

Engineers working overseas were expected to show versatility. John Brunton’s spell in charge of river traffic must have been a success, for he was asked to serve for a time as traffic manager on the Indus Valley Railway. His notes on the experience speak volumes on his attitude towards the people amongst whom he lived and worked:

It was at first thought that it would be difficult to get the natives to travel together in the same carriages on account of caste prejudices, but this proved a delusion. An hour before the time of a train starting, crowds of natives surrounded the booking office clamouring for tickets, and at first there was no keeping them to the inside of the carriages. They clambered up on the roofs of the carriages and I have been obliged to get up on the roofs and whip them off. Females were not allowed to travel in the same carriages as the men. A special carriage was allotted for them and I assure you the noise they made in chattering or rather screaming to one another rendered the identification of their particular carriage quite easy. The men travelling, always carry a roll of bedding with them, and besides they always sat cross legged on the seats, so I took out the seats of the 3rd Class carriages and they then squatted on their bundles on the floor of the carriage and thus economized space.

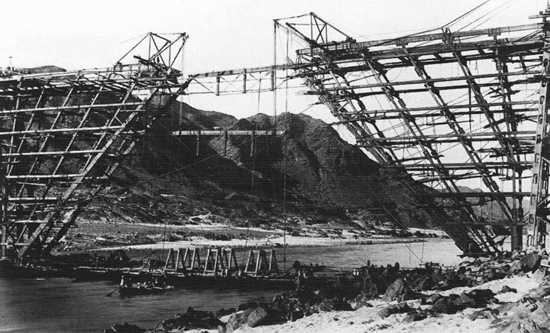

A section of the Attach Bridge being raised into place on the Northern Punjab Railway, December 1882

The early pioneering routes had proved their worth, but their true value could only be realized when they linked up with other sections of the developing system. The East Indian Railway had the simpler task, running over level plains (an idea of the terrain can be gained from the fact that in 1338 miles there was only one tunnel built and that was a modest 300 yards). It was not, however, free of problems. The route had to cross numerous rivers that were mere trickles in the dry season but became torrents thousands of feet across in the wet. The lines were continued on past the rivers long before the viaducts were completed. Temporary lines could be laid over the dry river bed, to be replaced by a ferry service in the wet season. James Meadows Rendel, the consultant engineer, turned to a type of bridge that had only recently been tried in Britain, the Warren truss, first used at London Bridge Station in 1850. It was built up of a series of triangular components, and it was a system well adapted for manufacture and testing in England for shipment overseas. Rendel was certainly impressed:

The principle of this bridge has much to recommend it for India. Composed wholly of wrought iron, in comparatively small parts and every part fitted in its place by machinery … the ease with which it can be fixed together and taken to pieces again without the slightest injury admits of it being proved in the workshop of the manufacturer, and of it being erected in its permanent position by the most unskilled and indifferent class of mechanics.

The viaducts were very impressive. Four were built to the pattern first seen in Robert Stephenson’s high-level bridge at Newcastle-upon-Tyne: a double-decker construction with railway on the top deck and road traffic on the lower. The grandest of these crossed the river Soane in twenty-eight spans, each of 150 feet; the Jumma was only slightly less impressive with a total length of over 3000 feet. The individual parts were made in England, the first coming from Charles Mare’s of Blackwall.

The most difficult river crossings were not, however, here but in the Punjab – not so much on the Punjab Railway itself which ran from Amritsar to Multon, but on the Punjab Northern State Railway from Lahore to Jhelum. The only real difficulty experienced on the Punjab Railway was that of getting a locomotive there in the first place. The first delivery was by boat to Ravi, up river from Karachi, and from there the journey overland was like some grand, spectacular procession: 102 bullocks were employed to pull and two elephants came behind to push. The Northern Punjab, however, had to cross three great rivers, including the Chenab. At the point where the railway was to cross, the river had already run for 300 miles, down from the mountains of Kashmir on its way to the Indus still 400 miles away. In its long journey, the river had picked up vast quantities of alluvial soil which had silted to depths of hundreds of feet, so there was no possibility of finding a solid foundation for the piers; and there had to be a great many piers for the river was crossed in sixty-four spans. The bridge was eventually constructed by sinking wells and building the piers on top of them.

The first stage was to construct groynes to divert the river so that a small sandy island was created. A circular kerb of wood was built, with a wedge-shaped cross-section, and laid on the sand as a base for the wall. The circular wall was then built up of brick on top of the kerb, and when it reached a height of about 12 feet, workmen clambered inside and began scooping away the sand so that the brick cylinder gradually began to sink under its own weight. When only a foot of brickwork showed above the surface, another 12 feet of brickwork was built on top of the first and the whole process repeated. As more and more bricks were added and the well sank ever deeper, so friction began to slow the sinking and literally hundreds of tons of rails had to be piled on top. The great danger the workmen faced was that of hitting quicksand, which could flow up through the tube and engulf them. When the well had reached the required depth it was plugged with concrete and filled with sand. Further stability was achieved by dumping concrete blocks round the walls – some 15,000 were made in situ. This immense operation was repeated over and over again, with three wells being sunk for each pier. Then the piers had to be protected from the ravages of the river which could scour up to 50 feet of sand away in one of its frequent floods. Boulders were stacked round the foot of the piers, but unfortunately no suitable stone was available locally. It had to be brought down river on cumbersome rafts that frequently overturned in the dangerous rapids. Finally there stood a bridge twice as grand as any on the East Indian – it was a full mile and three quarters long.

Looking west from the Attach Bridge as the railway heads off towards the mountains

A similar technique was used on the Empress Bridge carrying the Indus Valley State Railway across the Sutlej. This was a vast project with a huge workforce. A shanty town, protected by, as it turned out, inadequate flood banks grew up, which at one time held up to 6000 inhabitants. The engineer, James Bell, noted that once again the workforce suffered appallingly from disease:

In the worst season it was not uncommon for three men out of four to be laid up simultaneously with fever; and one year when a flood had broken into the place, one thousand workmen are believed to have died of pneumonia.

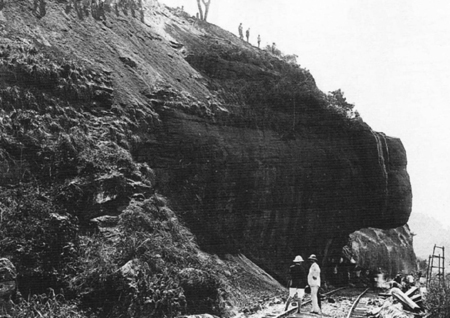

The difficulties faced on the East Indian were real enough but they seemed minor compared with those confronting the engineers of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway (GIPR). If it was to be extended inland then a way had to be found up the Ghats. Advice was available from the consultant engineer in England, Robert Stephenson, but the principal work of finding and building the route fell to the men on the spot, the Chief Engineer, James Berkley and the engineer who was to supervise the first line, Robert Graham. In the event there were to be two routes up the cliffs that rise to a height of 2500 feet: the first up Thul Ghat, the second up Bhore Ghat. The routes followed inclines at fierce gradients that ranged from 1 in 48 to 1 in 37, and these were no minor affairs: the Thul incline was slightly more than 9 miles long, the Bhore 154. Both involved the construction of bridges, massive embankments and tunnels, but their most distinctive feature was the zigzag route they took up the cliffs. This was achieved by including reversing stations, so that trains could crawl up the slope along the face of the cliffs to the station, then change direction and continue on, climbing in the opposite direction.

A huge workforce was required for construction. There was an early insistence on importing British navvies, but the men who could perform prodigious feats in northern climates were generally unable – and unwilling – to cope with the tropics. The ones that were brought some of their old habits with them. C.O. Burge described a rowdy crowd carousing on the Madras line. The native policemen tried to restore order, but with little success: ‘each navvy took two constables, one under each arm, and chucked them outside the railway fence.’ Some stayed on as overseers and gangers, and a number were to be found on the GIPR. Sir Bartle Frere was concerned about the situation and issued an edict that any European striking a native should be instantly dismissed and would forfeit his return fare which had been paid by the company. This news did not percolate down to the men on the ground. On an inspection of the works, he met a ‘big brawny navvy’ who was in charge of a native gang.

‘Well, my good man, you appear to be the manager here.’

‘Yes Sir,’ was the reply.

‘And how are you getting on?’

‘Oh, Sir, we are getting on very well.’

‘How many natives have you under your orders?’

‘Well Sir, about 500 on ’em altogether.’

‘Do you speak their language?’

‘No Sir I don’t.’

‘Well then, how do you manage to let these natives understand what they are to do?’

‘Oh Sir I’ll tell you. I tell these chaps three times in good plain English, and then if they don’t understand that, I takes the lukri [the stick] and we get on very well.’

The modern railways still use the routes pioneered in India. The greatest challenge facing the 19th century engineers was conquering the Western Ghats to join Bombay to the central plateau. The train is little more than a thin streak as it zigzags its way up the mountainside.

Further enquiries revealed that this navvy was in fact far from being the ogre he claimed to be, but was ‘a most kind hearted fellow, much loved by the natives under his charge, who would do anything for him.’

The Bhore Ghat represented an immense labour, with a rise of over 2000 feet, 25 tunnels and 22 bridges. As many as 40,000 were set to work and they suffered terribly, with nearly a third dying from disease. It was not just the labourers who were affected. Solomon Tredwell sailed from England to take a major contract, arriving at Bombay on 15 September 1855. By 30 September he had succumbed to fever and died. That was not the end of the contract. His widow, Alice Tredwell, simply took over and saw it through to completion. It was a daunting task, as the engineer Berkley admitted when he described the problems of gathering together a workforce:

This great force has not been collected without considerable trouble; it is not entirely supplied by the local districts, but is gathered from distant sources. Labourers sometimes tramp for work as in England, and on the same work may be seen men from Lucknow, Guzerat, and Sattara. The wants of the works have, however, been supplied by unusual exertions in sending messengers in all directions, and by making advances to muccadums, or gangers, upon a promise to join the work with bodies of men at the proper season. Country artisans and skilled labourers have their own methods of doing work, but are capable of improvement and are not averse to change their practice. For operations requiring physical force, the low-caste natives who eat flesh and drink spirits, are the best; but for all the better kinds of workmanship, masonry, bricklaying, carpentry, for instance, the higher castes surpass them. Miners are, on the whole, the best class in the country. The natives strictly observe their caste regulations, yet will readily fall into an organisation upon particular works, to which they will faithfully adhere, and in which they are by no means devoid of interest. Although they cling closely to their gangers, they will attach themselves to those European inspectors who treat them kindly. The effective work of almost every individual labourer in India, falls far short of the result obtained in England.

The account is interesting for the light it throws on attitudes. It could seem from reading this account that the ravages of cholera – it killed literally tens of thousands of workers – were chiefly notable for the delays they caused in the works. The account, in fact, raises more questions than it answers. It continues:

This photograph was found in an anonymous photo album, but appears to have been taken shortly after the opening of the Darjeeling-Himalayan Railway. It shows one of the reverses that enabled the little engines to climb the hillside.

One of the famous loops on the Darjeeling Himalayan

The fine season of eight months is favourable for Indian railway operations, but on the other hand, fatal epidemics, such as cholera and fever, often break out and the labourers are, generally, of such a feeble constitution, and so badly provided with shelter and clothing, that they speedily succumb to those diseases, and the benefits of the fine weather are, thereby, temporarily lost.

But why were the local navvies so badly fed and housed? The answer is that they had low pay because they could not perform as well as the British navvy. And the reason for this was partly that they were badly fed and housed and hence prone to disease. They were caught in a circle of poverty from which, it seems, there was no escape. The Europeans who employed them were not callous monsters, but followers of the rules that governed behaviour in England as closely as it did in India. It was the duty of the employer to pay no more than was absolutely necessary, otherwise the economy of the country would have been thrown into chaos: It has enabled the Company to draw largely and advantageously upon the resources of the country, both in labour and materials, without suddenly, or unduly affecting the public markets. The attitudes that permeate the thinking of those who came to build railways for the great Indian Empire are, not surprisingly, those of conventional Victorian England. They congratulated themselves for not disturbing the labour market and, at the same time, encouraging the spirit of entrepreneurship among a developing Indian middle class. There was general satisfaction at the success of one Indian contractor, as Berkley noted:

A Parsee contractor, Mr. Jamsetjee Dorabjee, has executed four main-line contracts as satisfactorily, as expeditiously, and as cheaply, as any of the European firms, and is now about completing his fifth, which comprises some of the heaviest works on the lines.

The railway company was a microcosm of British India. There was a willingness to encourage ‘the best’ of the Indians, combined with a deep-seated belief that the native could never be expected to take control of his own affairs. The guiding hand would be European.

The Company’s Engineers, Assistant Engineers, and Surveyors are generally Europeans, but one native Engineer has won his way to the office of Assistant Engineer, and has skilfully discharged its duties for three years. In the office establishment of draftsmen, accountants and clerks, all the situations have been held by natives. As inspectors of work, natives have been chiefly employed. As district inspectors of the line, when opened, native agency is already partially adopted, and is, by encouragement, gradually becoming more useful. The principle to be kept in view is, that only by means of European and native co-operation, can the great railway undertakings which are required in the Bombay Presidency, be accomplished with due despatch. European skill, experience, and management, are of primary importance, but native agency has proved much more valuable and efficient than was anticipated, and will, undoubtedly, be found capable of considerable and rapid growth, if it is adopted without prejudice, and is treated with equity; and if native employees of all classes are stimulated to improve themselves, by the assurance of their gradual advancement, according to merit.

The military took responsibility for building much of the Indian rail network: this sketch of a wooden bridge was made for the War Office by Lt. F.W.Graham.

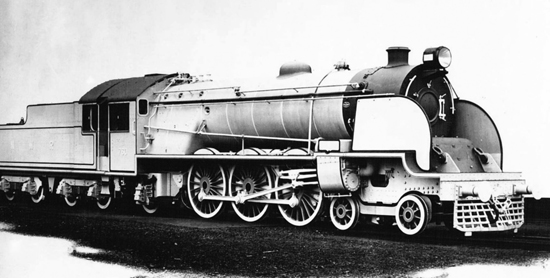

A Class A/1 2-8-4T built by Hudswell Clarke in 1913, seen here on a central Railway branch line near Nagpur

Yet the belief that Europe knows best was to lead to absurdities. Material was sent to India that was already available locally. For instance, creosoted sleepers were shipped out from England many of which by the time they reached the workings were split and useless. More incongruous was the use of wholly inappropriate technologies. India was not short of local building materials or of building expertise – how could anyone who had seen the great cities and temples of the Moghul Empire believe that it was? Yet it was still thought to be sensible to prefabricate booking halls and engine sheds and ship them to India. And what material was used for these buildings? Iron! Could anyone have seriously believed that an iron building was appropriate for a waiting room in the blistering heat of an Indian summer? Apparently they could and did. Fortunately for the future of Indian railways, there were others who realized that Indian methods had developed that were appropriate to the land and its climate and that the best results were likely to be obtained by combining the traditions of the East with the new technology of the West. It is worth quoting Berkley at length in a description of working methods where he explained how he eventually discovered that ‘some Indian modes of doing work, which seemed barbarous and clumsy, were the cheapest and quickest means which could be employed.’ He starts, however, with the negative side of working in India, where techniques were previously wholly unknown. Tunnelling provided an excellent example.

The whole process, except blasting and excavation, was unknown to native workmen. In the earliest tunnels, where the top was heavy, it was found, at first, impossible to keep native miners in the heading, and the timbering was done chiefly by Europeans and one or two Parsee carpenters, and the arch was keyed in by the former alone. Native miners use the churn drill, with which they are very handy, and they have sometimes been brought to work in pairs with the hammer, and strike with dexterity. They will work hard in close contact, and in the foulest atmosphere. They are careless in blasting operations, and consequently, the loss of life has been considerable; miners have been seen to fire a shot with a bamboo, and lie upon the ground while it exploded.

On the other hand when it came to more conventional building the old methods were shown to be perfectly satisfactory.

In staging and scaffolding it is only rarely, and in very large works, that the English example has been followed, nor are crabs and derricks so often met with as might be expected. The reason for this is afforded by experience, which has taught how cheap and expeditious it sometimes is, to use the native process. The bamboo coolies, or carriers of heavy weights, will lift their loads up the roughest staging and the masons and labourers require but little help, to find their way to the work at the top of the highest piers. The centering commonly adopted in the country, was to fill up the arch with stone and earth, and to shape the top to the form of the soffit, or at other times, to use almost a forest of jungle wood in scaffolding a rough centre. For these, centres of English construction have invariably been substituted, with, as may be conceived, immense advantage to the work.

Even today, quite sophisticated building sites in India can only be glimpsed through a thicket of bamboo scaffolding that looks to the uninitiated as if it needs no more than a mosquito to alight on one corner for the whole complex structure to topple to the ground. Yet it is a system which has, literally, stood the test of time.

It was not by any means always, or even usually, the fault of Indian contractors and workmen when things went wrong. Robert Maitland Brereton came to India to work on the GIPR in 1856 and his greatest difficulty lay with the European contractors and their poor, skimped work. Cement was left out in the sun, and instead of being regularly soaked was allowed to dry out and was then simply layered between stones in the form of a useless crumbling mass. Stone piers were supposed to be held together by ‘binders’, long stones that run the whole width of the structure to give added strength: these were simply left out and the stone which looked so fine was no more than an outer cladding. On one contract, No. 12, a score of viaducts and bridges collapsed. Brereton himself detected sharp practice on another contract and issued a critical report. He was inspecting other examples of the same contractor’s handywork when he was almost laid out by a blow on the head. He had just enough time to see the contractor’s agent wielding the stick. Brereton’s lip remained resolutely stiff: ‘I did not condescend, in the presence of the native workmen, to assault him in return, but quietly wrote out on a leaf of my pocket book an order for him to stop all masonry work.’ But whatever the problems met by the engineers, contractors and workmen, the GIPR, with its spectacular ascent of the Ghats, remains one of the great triumphs of nineteenth-century civil engineering.

For the young engineers who came out from Britain, India was an exotic experience and a challenge. C.O. Burge came from Ireland in the 1860s to work, or so he expected, as assistant engineer on the Madras Railway. His arrival was exciting enough. There was no harbour at Madras, so he came ashore in a ‘masula boat’, an alarmingly flimsy looking vessel about 40 feet long made of bamboo and leather. This was to carry him in through the surf. The boatmen hovered on the swell, picked a likely looking wave and headed for shore.

The momentum carries the masula boat high and dry on to the bank, when all the occupants who do not hold on like an attack of influenza are thrown into a jumble of boxes and portmanteaus, so that the astonished traveller is literally hurled into India.

He reported for duty and found he had arrived a fortnight before the rest of the young engineers were expected. So, on a simple first-come-first-served principle, he was promptly put in charge of an entire section – leaping up several rungs of the promotional ladder in one jump. He then went up country, an experience which constituted a crash course in self-sufficiency. The first stage of his journey was by train, and where the tracks ended he continued on horseback, his luggage and few sticks of furniture slowly trundling along by bullock cart. He stopped at simple guest bungalows or the homes of his fellow engineers spread out along the line, until he reached his section, nearly 40 miles from his nearest fellow-European colleague. It was the custom for the engineering staff to build their own bungalows, but common sense dictated that local practices were followed. Houses were generally built with a verandah all the way round providing shade in the summer and protecting the building from the downpours of the monsoons. Burge’s predecessor had scorned precedent and built a verandah along one side of the building only. The monsoons came, the rain lashed at the exposed walls, washing away the mud that held the stones in place, and the whole place came crashing down. Burge rebuilt it – in traditional style.

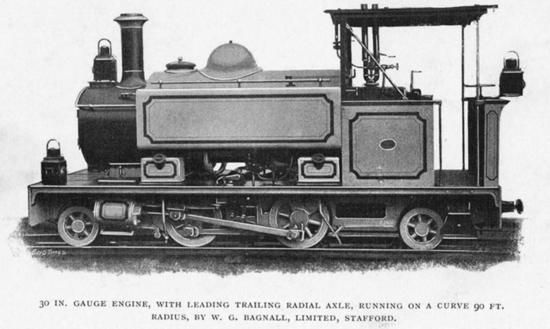

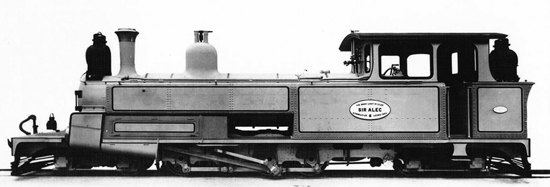

A neat Bagnall locomotive built for the Indian States Military Railway

He solved the problem familiar to other engineers in winter, the rivers that could turn overnight from trickles to waterways three times the width of the Thames in London. He learned to improvise. Temporary tracks were laid across river beds in the dry season, which were used not just for construction purposes but for regular passenger services as well. Above all, he learned to delight in the mixture of racial types, men and women, who made up his workforce. Because of a local labour shortage, he found himself employing workers from all over India including Afghans and Pathans who arrived with alarmingly long, sharp knives stuck in their belts. ‘Their features, or sometimes the absence of them showed that they usually settled their differences by private enterprise without troubling Government legal machinery.’ Some learned English, but inevitably produced the occasional howler. Three men appeared with a note which read, ‘Sir – herewith I have the honour to enclose three bricklayers’. And official documents combined the starchy language of bureaucracy with startling outbursts of colloquialism: I have the honour to inform you that Mootheswamy and Soobarou have booted it on Friday last, and I have replaced them by two good masons.’ Men like Burge enjoyed India and served the country well. They were not always so well served themselves.

A Bombay& Baroda Central locomotive.

In 1868, Robert Brereton was appointed chief engineer for the Calcutta and Nagpur line. He picked his own staff and was confident enough to tell the Board he would have the work finished by May 1870, eighteen months ahead of schedule. He drove the storekeepers mad, harrying them for materials. One of the main sources of delay on a good many lines was lack of even the basic materials – so that gangs would be sent around with, for example, a full stock of rails and sleepers but no chairs. Brereton made sure this never happened. He also followed the American practice of laying temporary track over obstacles, ranging from rivers to gulleys, to keep his supply lines open. Even so, there were some elements over which he had no control. In 1869, cholera came to the Nerbudda valley: hundreds died and workmen fled from the area. Brereton himself succumbed and was lucky to survive. In spite of this, the line was ready as promised, at which point the successful engineer was given his notice with not so much as a thank you.

The railways discussed so far were all built as part of the usual process of establishing a rail network for a country that would carry the people and commerce of a nation. In India, other considerations came into play: some railways were built primarily to meet military rather than civil needs. The outbreak of the Afghan wars in the 1870s brought a new urgency to the need to provide rails to the troubled North-West Frontier. The result was the Kandahar Railway which was planned to run from Sukkur on the Indus, a spot which could be supplied by barges and steam tugs, north to Kandahar, actually across the old Indian frontier in Afghanistan. The first stage was only to run from Sukkur to the entrance of the Bolan Pass through the mountains. That presented problems enough. First came the broad plain, crisscrossed by hundreds of irrigation channels, then 40 miles of dense jungle, followed by the greatest challenge of all, 94 miles of ‘dry, barren, treeless plain’ crossed by spill channels that would remain empty for years on end, then quite suddenly be filled to overflowing by flash floods. The natural difficulties were, by any standards, bad enough but construction was made doubly difficult by the demands of time.

South India Railway locomotives beside a mixture of metre gauge and Indian standard gauge tracks.

There was no time to arrange for special supplies to meet the needs of the builders – any kind of rail or sleeper that was available had to be used. An extraordinary collection of hardware was soon accumulating on site. By sea from Bombay came enough rails for 50 miles of track, but sleepers for only 25; and even the rails were a mixture of new ball-headed steel and worn-out track uprooted from heaven knows where. Other lines rendered up an equally bizarre mixture of pot-sleepers, double-headed chair roads and flat-footed track – and even that could be sub-divided into many different types. Somehow all had to be put together by an inexperienced workforce to make a coherent whole. It could only work if a strict set of rules was laid down, so that the right sleepers finished up fastened by the right chairs to the right rails. The secret lay in organization: each train was to be marshalled so that rails came first, fastenings second, then sleepers. It never worked. Each train was a higgledy-piggledy mess of trucks that even after hours of shunting disgorged material that then had to be sorted by hand. The best drilled gangs in the world would have been hard pressed to make sense of this chaos; and the builders of the Kandahar Railway were not blessed with the best drilled gangs. Every time a new type of track had to be laid it was as if the whole job was being started again from scratch. It was, as the engineer James Bell’s reports make clear, all very frustrating.

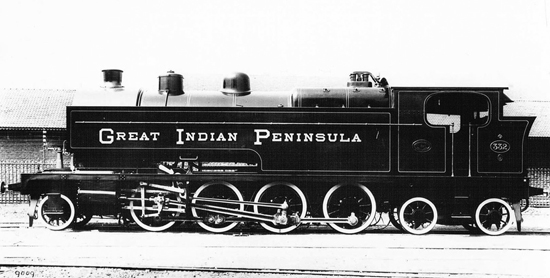

A Great India Peninsula Railway locomotive with an inspection seat in the railed compartment at the front.

For instance, a man might be employed one day on boring sleepers and spiking the flat-footed rail, and the next day he would be thrown out of work on the commencement of the pot-road, until he could be taught to fit and cotter tie-bars to pots, set the pots out for the linkers, or drive keys.

It was an administrative nightmare. Just as difficult a problem was presented by the logistics of getting material moved on the last lap of the journey to the advancing railhead. Here local technology took over and proved itself to combine practicality, cheapness and a degree of sophistication. The engineer responsible for much of the work, George Moyle, described the arrangements for supplying the plate-layers:

This was done by bullock-carts, a fair number of which were obtainable in the districts through which the line passed. These carts cost complete but £1 10s., they are easily and readily repaired, and are constructed to travel over roads of the roughest description. They are built of rough-hewn jungle wood. One end of the wooden axle, which revolves, is square, and the other round, so that one wheel is fixed on the axle, and the other loose; this arrangement enables the carts to be turned about very easily. To enable these carts to be used, service roads had to be constructed on each side of the line, and carried over the numerous canals on rough timber, or floating bridges.

The materials were not the only problem: men had to be looked after as well. The original idea had been to make up a long train of wagons, each equipped with an awning, which when shunted together would make a crude tent some four hundred feet long. This was not popular, but the camping train did provide a service as mobile shop, hospital, stores shed and treasury. The men preferred their own solution:

For housing primarily the earthwork men and ultimately the platelayers, the surveyors began the erection of temporary sheds of reed mats at every 6 miles. But as they could not get enough camels or carts to carry out the mats, only two such camps were constructed. The plate-laying labourers took kindly to the mat-work sheds, and as the temper of the men was too precarious to warrant much interference with their predilections, the sheds were continually rebuilt at every 3 miles, and kept about one hundred men employed on their erection, while the renewals of mats and bamboos (about a wagon load in every train) occupied carrying capacity that could ill be spared. The mats were each about 4 feet 6 inches square. A single row of mats on edge formed the back wall of the shed, and another single row of mats laid flat formed the roof. The sheds were built with their backs to the north, and though pervious to wind and rain, they broke the force of the wind so as to make it safe for men provided with blankets to sleep under them so long as it did not rain.

Rain was certainly not the problem; water supply as the lines approached the desert was. A reservoir was established at the furthest point of the canal system, but beyond that water tanks had to be sent out by train every day. Perhaps the greatest difficulty of all was in persuading men to come and work in the desert, even when the arrangements for water supply were explained. This is not too surprising. The climate was vicious – a boiling hot day could be followed by a night so cold that ice formed on the water barrels. Other sections presented their own unique problems to the administrators, and the jungle in particular seemed to have been specially designed to create an environment where chicanery could thrive:

Throughout 45 miles the line passed through heavy jungle, which afforded excellent cover to such drivers as desired to decamp with their bullocks, shirk work, or free themselves of their load. To prevent such irregularities, it was found necessary to post patrols of irregular cavalry on both sides of the line, and along the main roads by day, and by night to form the carts into a laager presided over by sentries.

The demand on the carts was immense. It was estimated that every mile of track laid needed 600 carts. The bulk of the traffic was made up of rails, 500 per mile but only 2 per cart, and sleepers, 1600 at 8 per cart load. The wonder is that the line got built at all.

At this time the military were not entirely given over to their more obvious tasks, nor were they notably less imaginative than their civilian counterparts. R.E. Crompton was an officer in the Rifle Brigade, but steam engines were his passion. He built a small steam carriage while still at school but his boldest experiment was reserved for India. That railways were infinitely better than the bullock carts, swaying and creaking down every Indian road, was beyond dispute – but did they have to be railways! Why not build a steam engine to travel on the common roads? He proposed a ‘Government Steam Train’ to run on the newly improved Grand Trunk Road that stretched out northwards from Delhi. The engines were ordered from Ipswich, and one of these, Ravee, showed its mettle by outpacing a good train, on the adjoining railway. Crompton wrote, enthusiastically, ‘though our loaded train weighed over forty tons, we were making speeds well over twenty – probably nearer thirty – miles an hour.’ The Government Steam Train had a brief, but not inglorious, career. Most military endeavour was bent towards more serious ends, and military engineers were to face some of the sternest challenges India could present.

Work had stopped on the Kandahar Railway long before the final objective had been reached simply because the political climate had changed and it was no longer diplomatic to continue it. Then in the 1880s Russia again began to make aggressive noises and the old North-West Frontier manoeuvres began as if nothing had happened to interrupt them. The railway that had been declared wholly unnecessary a decade earlier was now an essential supply line. Diplomacy, however, was not yet ready to admit to a complete volte face – surveyors were sent out to work on the Harnai Road Improvement Scheme. There was no mention of the fact that this particular road was to be improved by the laying of steel rails. It was a feeble pretence, and the route soon had a new name: the Sind Peshin State Railway.

The military engineer’s view was uncompromising:

The line does not wind its way through smiling valleys to the breezy heights above. It traverses a region of arid rock without a tree or a bush and with scarcely a blade of grass – a country in which Nature has poured out all the climatic curses at her command. In summer the lowlands are literally the hottest corner of the earth’s surface, the thermometer registering 124°F in the shade, while cholera rages, although there is neither swamp nor jungle to provide it with a lurking place. In winter the upper passes are filled with snow and the temperature falls to 18° below zero, rendering outdoor labour an impossibility. The few inhabitants that the region possesses are thieves by nature and cut-throats by profession, and regard a stranger like a gamekeeper does a hawk. Food there is none, and water is often absent for miles. Timber and fuel are unknown and, in a word, desolation writ very large is graven on the face of the land.

The footplate crew pose beside an East India Railway locomotive

The line was built through what was, in every sense, hostile territory. The route ran up the Nari River gorge to a station aptly named Tanduri, or ‘Oven’, where the only water came from a pool mainly inhabited by crocodiles. The line was regularly raided by local tribesmen, but weather and disease proved the more lethal enemies. In 1885 cholera wiped out 2000 of the 10,000 workforce.

In 1887, 19.27 inches of rain were recorded, six times the average. Then there was the terrain. The route climbed inexorably from an altitude of 433 feet at Sibi to a summit of 6537 feet. Quite the most spectacular feature along the route was the Chappar Rift, a gorge with almost vertical rock walls that lay right across the line of the track. The railway circled as though eyeing up the adversary, then dived into a tunnel, to emerge at the very edge of the chasm. Then with one mighty leap in the form of a 233-feet-high bridge it spanned the rift to disappear into another tunnel on the far side. The spot was so inaccessible that no heavy machinery could be brought in and only light drills could be used. Gunpowder and dynamite were used for blasting and the debris was all cleared away by hand. Worse was to come at Mudgorge, a spot that suited its name exactly, a desolate valley with a floor of mud, made up of an unholy mixture of shale, clay and soft stone. It was firm enough in winter but in summer turned into a sea of porridge. Thousands of feet of rail were laid only to be washed away in storms until the engineers finally decided to dig a cutting and cover it over to provide a tunnel secure from the elements. Even then the elements had the last word. In 1942, a flood roared down Chappar Rift washing away rock, scree and the railway. There was no chance of repair: there was nowhere left to put the tracks. The life of the Sind Peshin Railway was ended.

This light railway locomotive built for India is based on an original design for the Leek & Manifold Light Railway.

There are other spectacular railways in India. The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, opened in 1880, climbs from the heat of the plain to the cool of the hills, rising to an altitude of over 7000 feet in 51 miles during the course of which it winds round itself in a series of loops. The most dramatic of these at Agony Point was built with a curve of just 59½ feet radius. It was almost possible for the engine of a long train to be passing on a bridge over its own brake van. Yet even this line never posed the problems set on the Sind Peshin. This was perhaps India’s engineers’ greatest challenge.

Across the border in Burma, no railway building began until the 1870s when the Rangoon to Prome line was built, largely using convict labour. Military engineers who had been working in India often found themselves being shunted across the border. India provided excellent training for the rigours of Burma. Colonel, later Sir Gordon, Hearn worked in 1899 as surveyor for a line from Mysore to Tellicherry which included that inevitable obstacle facing all west coast lines, the Ghats. In this case they consisted of hills rising to a height of 2000 feet and covered in dense forest. His predecessor, a young officer, had tried to follow a cart track, but that had been no help. The chief engineer, universally known as ‘Buff-Puff Groves, told him to strike out into the forest which numbered among its perils large numbers of lethal pit vipers. The young man said, ‘As a family man, I must decline’, and went home. Hearn was given the dubious distinction of being appointed in his place. He did not record meeting any of the deadly snakes but he met almost everything else. Wild elephants roamed the forest and during the monsoons which produced the largest proportion of the 400 inches of rain that fall in the area in a year, there was an infestation of leeches. Everyone except Hearn got malaria. And these were just additional problems tacked on to the main task of pushing a line through forest where the trees were up to 150 feet high.

In 1906, Hearn went off to Burma to work on the line from Thazi to the plateau of the southern Shan State. Work had begun two years earlier but Hearn was not happy with the route so he set off as he had in India to walk through the forest. On the first day he covered 18 miles tramping through rough country, until he found a better route through the hills. An extension of the line involved more walking, over 200 miles in three weeks with Burmese assistants. ‘The speed with which the Burmans build a shelter for the night made it unnecessary to carry a tent, but they are not industrious workers, and being sensitive to the sun’s rays would not toil when the sun was high. In fact, the only sound to be heard at mid-day was a snore!’ Noel Coward, it seems, was right about mad dogs, Englishmen and the midday sun. Burma presented very real difficulties to the engineer. Lieutenant Colonel L.E. Hopkins surveyed the line from Mandalay to the Chinese border near Kunlong. It rose steeply from the plain and the first thousand foot climb was so rapid that the route would have had to zigzag with no fewer than four reversing stations. The other engineer working on the same line, Lieutenant W.A. Watts-Jones, had the misfortune to inadvertently wander across the Chinese border and was executed for his mistake. In the event the difficulties proved too great and the line was never built.