THE FIRST NEANDERTHALS DID NOT arrive overnight, but seem to have gradually evolved from Homo heidelbergensis populations within Europe. The earliest phases see similar habitat use and technology to the Hoxnian populations, but as they evolved, so too did their tools together with the gradual adaptation to the grassland steppes that were beginning to spread from Eurasia across to the western fringes of Europe. Britain, as with other areas of northern Europe, had endured another cold episode of 30,000 years from 360,000 years ago. Although less severe than the Anglian, Britain must have been depopulated by all but the hardiest of animal and plant species. As climate warmed and sea-levels once again rose about 330,000 years ago, populations returned at the start of what we can call the Purfleet Interglacial or Stage 9.

Recolonisation was now more difficult due to the recently formed Strait of Dover and the deeper North Sea Basin, but among the returnees were humans. One of the frustrations of studying this period is the rarity of finding stone tools in association with biological evidence. That humans were here in large numbers seems clear from the many thousands of handaxes and other artefacts that have been found in the Thames and Solent river terraces (Figure 108). In the large gravel pits on the Lynch Hill Terrace of the Thames, in the Hillingdon, West Drayton and Yiewsley areas of west London, over 1,500 handaxes were recovered, but precious little bone. The Hackney gravels of northeast London also cover this episode with abundant artefacts, but little fauna or flora. The same is true in the Solent River and other river systems across Britain. To understand the environments of the Purfleet Interglacial we have to turn to other sites that are largely devoid of human artefacts.

FIG 108. Map of southern Britain showing palaeogeography about 300,000 years ago with sites mentioned in the chapter. (Craig Williams)

THE PURFLEET INTERGLACIAL

We can start with a journey up the Thames, where a series of sites provide windows into the environments of the Purfleet Interglacial. We can then try and understand how humans figured in these landscapes. We begin near the estuary of the ancient river near Colchester in Essex.

Cudmore Grove

On the northeast corner of Mersea Island lies the site of Cudmore Grove (Figure 109). Deposits were first noted by Dalton in 1908, but it was only after coastal erosion in the 1980s that the Thames river channel was more fully exposed in the cliffs and on the foreshore (Bridgland et al., 1988; Roe, 1995). The channel is filled with clays and organic muds that preserve a rich vertebrate assemblage, but also molluscs and ostracods. Perhaps the most important aspect of the site is the pollen from over 7 m of the sequence that allows us to reconstruct the vegetational succession of at least part of this interglacial.

FIG 109. The organic muds of the channel in the cliff at Cudmore Grove. (Simon Lewis)

In many respects the development of new forest from the start of the interglacial to more mature deciduous woodland at the warm peak is similar to that of the Hoxnian. The earliest vegetation is dominated by pine and birch with the occasional occurrence of oak, alder and hazel. The channel edges were fringed by pondweed and Common Bulrush with grasses beyond. A warming in climate is shown by the change from boreal to more deciduous woodland in particular with the dominance of oak, but with smaller numbers of ash, hazel and lime. Fewer aquatic plants might show more estuarine conditions with increased salinity. The final part of the sequence shows a sudden change to alder carr, with branches of this wood preserved in the deposits. Oak still dominated the woodland beyond with the development of hornbeam and spruce, while more open ground supported grasses, heathers and ferns.

The molluscs and ostracods are less well preserved, but show a slow-flowing river close to its estuary with a reduction in brackish waters through the sequence. The vertebrates come from the middle part of the interglacial and have provided a remarkable range of smaller taxa (Holman et al., 1990). There are 14 amphibians and reptiles, seven of which are non-native to Britain today. Alongside Crested Newt, Common Toad (Bufo bufo), Grass Snake and Common Lizard (Zootoca vivipara) are the more exotic Moor Frog, Marsh Frog (Rana ridibundus), Viperine Water Snake (Natrix maura) and European Pond Terrapin. They reflect a mix of wet, damp and dry habitats in a temperate climate with summers warmer than in Britain today. The mammals indicate a similar array of environments with aquatic habitats, shown by Water Shrew, water vole and European Beaver (Castor fiber), while woodland is suggested by Red Squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris), Wood Mouse, Macaque and Roe Deer. If this was the environment close to the estuary of the Thames, what was it like upstream?

Purfleet

From its estuary the course of the ancient Thames ran roughly parallel to the modern Essex coast, passing near Southend, Basildon and Thurrock. After 50 km against the current you would reach Purfleet and it is this site that has given its name to the interglacial of Stage 9. Along the northern flanks of the Thames to the east of London a series of enormous gravel and chalk pits lie within the boroughs of Purfleet, Grays and Thurrock. The pits have long-since finished production and have given way to the Lakeland Shopping Centre among other ominous developments. The two adjoining pits of Bluelands and Greenlands at Purfleet preserve a long sequence of sands and gravels, silts and clays that were laid down by the Thames and span a large part of the interglacial (Figures 110 and 111). The richest sediments are Beds 3 to 5, which contain pollen, ostracods, molluscs and a variety of vertebrates (Palmer, 1975; Schreve et al., 2002; Bridgland et al., 2013).

FIG 110. Map of the Purfleet area showing Greenlands, Bluelands and Botany Pits from the notebook of John Wymer.

FIG 111. Section at Greenlands Pit, Purfleet. (Danielle Schreve)

Through the sequence the ostracods show a change from fast-flowing water in Bed 3 to slower conditions in Bed 4, returning to a more rapid flow in Bed 5. Although freshwater species are dominant, the presence of Cyprideis torosa indicates a tidal influence throughout, a long way upstream from the estuary at Cudmore Grove. The ostracods have been used to estimate temperatures with average Julys between 16 and 21°C and Januarys between –3 and 3°C. The summers were similar or possibly warmer than southern England today, while winters could have been a little cooler.

Molluscs are best preserved in the ‘Greenlands Shell Bed’ of Bed 5. They are dominated by species such as Bithynia tentaculata, Pisidium henslowanum and Belgrandia marginata that live in slow-moving, large rivers. The latter is no longer native to Britain, today being found in northeast Spain and southern France, and, like the ostracods, hints at warmer summers. Other aquatic taxa show areas of deep water with little plant growth and towards the top of the sequence an increase in current. Although rare, terrestrial taxa show marsh, grassland, scrub and woodland extending back from the river edge.

It is also the Greenlands Shell Bed that has provided the most vertebrates. Fish include eel, Pike, Bream, Dace (Leuciscus leuciscus), Roach and Perch, but also European Sea Sturgeon, which breed upstream before returning to the coast. A range of frogs and toads included the Agile Frog, which is no longer native to Britain, although still widespread across Europe. It has particularly long back legs and can jump up to 2 m in height. The mammals are well represented with several species of shrews and voles, together with European Beaver, Macaque, various deer, horse, bison and straight-tusked elephant. We also see the return of Spotted Hyaena, which had been absent in the Hoxnian, but seems to have recolonised during the Purfleet Interglacial.

Unfortunately pollen was poorly preserved with differential survival of some types, such as pine. Overall it shows a forested environment with areas of grassland and aquatic plants. The woodland, other than pine, shows stands of alder with other water-edge trees such as willow and ash. Just as with Cudmore Grove, oak was a dominant tree in the deeper forest with lime, elm and spruce.

The woodland and grassland banks of this large, slow-flowing river were also occupied, at least occasionally, by humans. There is an intriguing paucity of flint artefacts from the main part of the sequence of Beds 3 to 5, other than occasional flakes and the odd flake tool or core, but some evidence of handaxes and their manufacture in the overlying Bed 6. But by this time climate had begun to cool, so where are these elusive humans?

Hackney Downs

To continue the journey upstream, from Purfleet it is only 15 km to the confluence of the Thames and its north-bank tributary the River Lea. Turning right up the tributary today you see the Olympic Stadium on your right and soon enter the low-lying Hackney Marshes. But 300,000 years ago the course of the Lea was on higher ground to the west depositing a large spread of sediments known as the Hackney Gravels. Ancient courses and floodplain deposits of the river have occasionally been found within the gravels, one such being on the Nightingale Estate. It was not quite as charming as its name suggests, once being a notorious development of 1970s’ tower blocks that overlooked Hackney Downs. But redevelopment from 2000 created a new ‘urban village’ with undoubted improvements to the area. One of the side benefits was access to underlying Pleistocene sediments, in particular a rich fluvial sequence through the floodplain sediments (Green et al., 2006).

The sediments consist largely of sands and occasional gravel, and from the associated pollen they seem to have been deposited during the peak part of the Purfleet Interglacial. As with Cudmore Grove, the woodland was dominated by oak with lime, elm and Field Maple (Acer campestre) growing on the drier ground, while damper areas supported stands of alder, willow and ash. There is exceptional preservation of the plant macroscopic fossils with 85 taxa, often identifiable to species, which further embellishes our knowledge of the various floodplain habitats. The wet, muddy edges of the river were vegetated with plants such as Three-stamened Waterwort (Elatine triandra) and the sedge, Brown Galingale (Cyperus fuscus). The latter is often associated with grazing animals. Through time, taller reedswamp developed also supporting the member of the sunflower family, Hemp-agrimony or Holy Rope (Eupatorium cannabinum), Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) and the Common Nettle (Urtica dioica). Drier areas of the floodplain had disturbed soils as shown by the growth of Fool’s Parsley (Aethusa cynapium), Parsley-piert (Aphanes arvensis), Thyme-leaved Sandwort (Arenaria serpyllifolia) and Long-headed Poppy (Papaver dubium). On the more stable grasslands, Rough Chervil (Chaerophyllum temulum) and the medicinal plant Common Selfheal (Prunella vulgaris) also grew. The woodland supported shade-tolerant species such as Three-nerved Sandwort and the now-extinct Pyracantha clactonensis. This was probably a relative of Firethorn or Pyracantha coccinea, common in gardens today.

This full range of habitats is reflected in the beetle remains, with an amazing 254 taxa. Running water with shallow rapids is indicated by a variety of aquatic species, such as Oulimnius troglodytes and Normandia nitens, which live between the stones on river beds, although other taxa show more pond-like conditions. Clay, silt or sandy banks often close to slow-flowing or stagnant water are shown by various species of Bembidion. To these can be added the meadow and woodland taxa, such as the weevils, Longitarsus and Haltica, which feed on weeds in open areas, or the Cockchafer (Melolontha melolontha) and Rhynchaenus quercus, both of which are nourished by oak leaves. Although there are virtually no carcass-eating beetles, there are a large number of dung beetles, with several species of Aphodius and Onthophagus, indicating the presence of medium and large mammals, whose presence does not otherwise survive. Some of the beetle species no longer inhabit Britain, but have modern distributions in central or even southern Europe. Together they suggest average summer temperatures of about 18°C and average winters of between –4 and 1°C.

Drawing together the evidence from Cudmore Grove, Purfleet and Hackney Downs we have a clear picture of mixed oak woodland around the valley edges supporting a range of forest plants and animals, with straight-tusked elephant, Red, Fallow and Roe Deer, Macaques and the smaller mammals of Red Squirrel and Wood Mouse. The slow-flowing river wended a course across the grassy floodplain with larger herds of horse and bison. Reedswamp fringed the river where shallow pools and quieter stretches supported a rich aquatic plant life populated with a wide range of fish from eel and Pike to bream, Dace and Perch. Upstream the flow was broken by occasional rapids and the damming activities of beavers. Overlooking the scene were the hyaenas, but where were their competitors the humans?

Handaxe makers and the Purfleet Interglacial

Upstream of Hackney Downs lies the area of Stoke Newington, a suburb of London first built from the 1870s. Fortunately for Palaeolithic archaeology a certain Worthington George Smith was born a couple of miles south in Shoreditch in 1835. His baptism entry states his residence as Whitmore Road, which by pure chance I can see as I look out of my office window. He would have been amazed that many of the collections that he amassed over the following decades would be stored only a stone’s throw from where he was born.

With an interest in architecture, history and natural history, and with a talent for drawing, Worthington Smith became an architectural draughtsman, later working freelance with particular success as a botanical illustrator. He was perhaps best known as a mycologist, writing several books on British fungi. But among his other passions was the growing subject of Palaeolithic archaeology. By now he had moved to Mildmay Grove near Dalston and it was in the areas to the north of here that the suburbs of Stoke Newington, Clapton and Stamford Hill were being built. With the publication in 1872 of John Evans’s The Ancient Stone Implements, Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain came the first description of the many handaxe locations around England. Among these Worthington Smith noted the description of handaxes coming from the spreads of gravel between Hackney Downs and Highbury. With new houses came foundation and drainage trenches and it was not long before Smith devoted much of his spare time retrieving from workmen large numbers of flakes, flake tools, cores and of course handaxes. This in itself was unusual, with most other collectors being only interested in the more elegant handaxes. Worthington Smith assiduously collected everything, marking each object with a location, making detailed notes and often accompanied by beautiful illustrations (Figure 112). Much of his work here, at neighbouring sites and indeed as we will discover later, in Bedfordshire, was published in Man the Primeval Savage in 1894. Today his collections still form some of the most important assemblages for this period.

FIG 112. A handaxe from Lower Clapham drawn by Worthington Smith. (Courtesy of Luton Museum)

FIG 113. An extreme pointed handaxe from Cuxton, Kent. (Francis Wenban-Smith)

The Hackney Gravel spreads from Hackney Downs in the south towards Stamford Hill in the north and seems to have been deposited before, during and after the Purfleet Interglacial at the confluence of the Thames and River Lea. The handaxes take a variety of forms, but are usually pointed in shape and are associated with elegant scrapers. Other river systems also have surviving spreads of gravel from this period, whether it is the Thames in west London, the Medway in Kent, or the Great Ouse in Bedfordshire. All of them have produced large numbers of handaxes. One of the hallmarks of these assemblages though is the diversity and sometimes extremes in handaxe form (Wenban-Smith, 2004; Bridgland & White, 2014). They are very often pointed, rather than ovate in shape, but some are enormous in size. The largest is from Furze Platt, near Maidenhead, weighing in at 2.8 kg and 30.6 cm in length. Almost as large is the ‘Beast of Biddenham’ from near Bedford, or the handaxe from Cuxton in Kent with an extreme form of tapered tip (Figure 113). Were these really the general-purpose butchery tools that we see at Boxgrove and other earlier sites, or did they have a different purpose? Most handaxes were still probably used for butchery, but the rare large forms seem less practical for cutting and disjointing carcasses. In fact they seem to have little practical function except perhaps as an individual display of workmanship and prowess. It has even been suggested that skill in handaxe manufacture might be one of the more visible criteria for selection of sexual mates (Kohn & Mithen, 1999). Whether this is the case or not, we can certainly see the individual at work and perhaps the wide range of other handaxe forms reflects some form of group identity as with the twisted ovates in the Hoxnian (see Chapter 7). But until there is better resolution in the dating of these gravel spreads, such questions remain difficult to answer.

One of the other problems is working out when humans first appeared in the interglacial. The river terrace gravels, from which most handaxes derive, were deposited over a wide time period from the end of stage 10 through the Purfleet Interglacial of Stage 9 to the beginning of Stage 8. In the absence of biological remains, though, there is little indication of which parts represent the Purfleet Interglacial. Where fauna and flora survives in situ, there is almost a complete absence of human evidence. Is this perhaps telling us something? One thing we can surmise is that during the peak of the interglacial Britain was probably an island, so is the paucity of artefacts at Purfleet, Cudmore Grove and Hackney Downs simply a reflection of Britain’s isolation from mainland Europe? Did in fact humans arrive prior to this as sea-levels were rising at the beginning of the Purfleet Interglacial, before severance by the sea? As an isolated population were there sufficient numbers to survive into the full interglacial? An alternative, or perhaps complementary, explanation is that humans arrived late in the interglacial during the complex series of cooler episodes after the warm peak (see Chapter 3, Figure 21). At this time sea-levels would again have been lower, allowing easier access to Britain. Only further work and new sites will answer these questions. Although there are many unknowns, it is clear that handaxes in a variety of forms were the main tool of choice. However, it was soon to be replaced by another tool and this we can see at the very end of the interglacial.

The beginnings of Levallois

To return briefly to Purfleet, at the top of the sequence at Greenlands Pit is a gravel bed called the ‘Botany Gravel’. This is interpreted as being deposited during the tail-end of the interglacial or early in the following cold stage. Its name derives from the nearby Botany Pit, 1 km to the west, where a thicker exposure of the same gravel was being quarried away to use the chalk beneath. The quarry expanded around 1960 and due to the assiduous observations of an 18-year-old was soon to become a site of international importance.

In July 1961 Andrew Snelling and friends from a WEA archaeology class were visiting the quarry to investigate a report of Roman pottery and noticed prolific numbers of artefacts that were being exposed by the gravel workings. In 1958 he had been a founder member of the Hornchurch Historical Society, worked with the Wymers at Swanscombe in 1960, and in early 1961 had carried out excavations at the Clactonian site of Globe Pit, Little Thurrock. He was working as a laboratory assistant in a firm of manufacturing chemists and had also enrolled at the Institute of Archaeology to undertake the first year of the Diploma in Archaeology, The Food Gatherers. Where the spare time and energy came from is still a mystery, but soon after the discovery of artefacts at Botany Pit Andrew and friends were excavating every Sunday, recording and recovering a huge flint assemblage (Figures 110 and 114; Snelling, 1975). Visits by John Wymer and Professor Fred Zeuner of the Institute of Archaeology provided guidance and official blessing (Wymer, 1968). Andrew’s work was concluded by 1966 and sadly for archaeology a change of career took him into the banking world. Despite a profession elsewhere, he has maintained a lifelong fascination with Palaeolithic research. Over 55 years after his discovery at Botany Pit he is still an active field-worker and in September 2015 I had the pleasure of working alongside him cutting sections through the deposits at Swanscombe.

FIG 114. The chalk and remnant overlying gravel at the Botany Pit, Purfleet, in 1962. (Andrew Snelling)

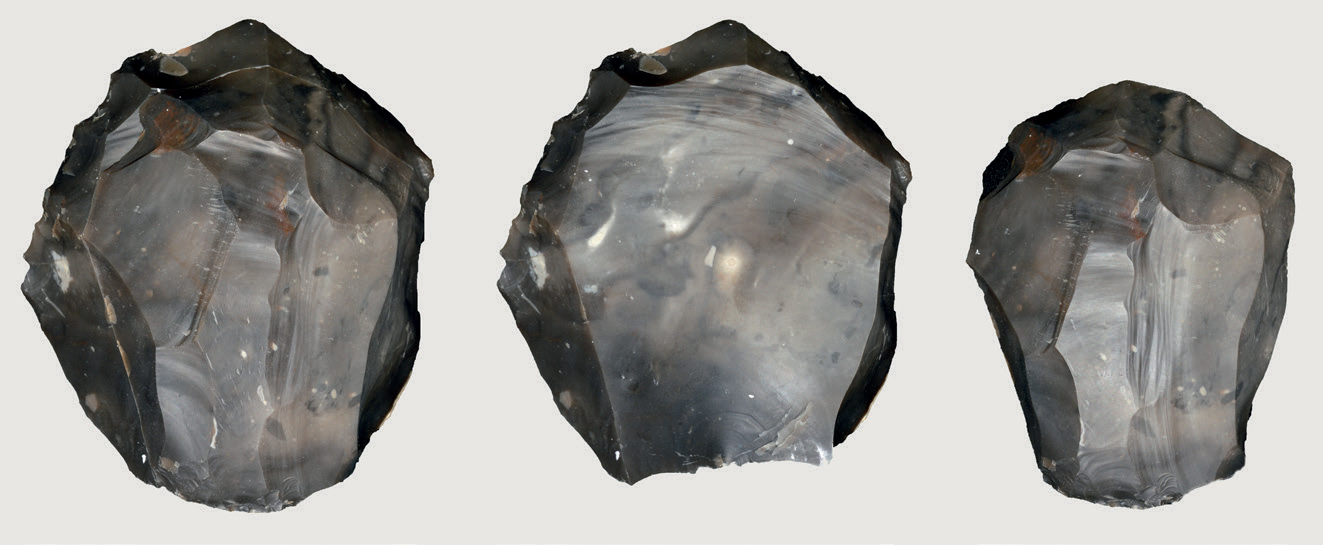

FIG 115. Experimental Levallois knapping by John Lord. Core and refitted flake, core, flake.

The assemblage from Botany Pit consists of almost 4,000 flint flakes, cores and occasional handaxes, now stored at the British Museum. The artefacts are unusual. Other than a few handaxes, the cores and flakes relate to a new technology called Levallois. The name comes from a suburb in northwest Paris, where in the 1860s unusual types of core were first identified (Reboux, 1867). Blocks of flint were prepared by initial flaking down the sides of nodules, which were then flaked across the upper surface to predetermine the shape of the final flakes (Figure 115). This technology is now synonymous with Neanderthals and the Middle Palaeolithic. Similar ‘prepared core’ technologies have been identified across Africa and Eurasia and for some recent researchers it was a technology that was introduced into Europe from Africa (Foley & Lahr, 1997). But the interesting aspect of the Levallois cores from Botany Pit is that it is a primitive form of this technology, suggesting that it developed locally, rather than having an African origin. The full flowering of Levallois, however, was to wait until after the following cold period of Stage 8.

HARNHAM

The cold period of Stage 8 was comparatively mild compared to the Anglian or indeed some of the subsequent glaciations. There are no glacial sediments in Britain that have been attributed to this period, although it is likely that the higher ground and more northerly areas were covered by ice. Could people survive further south? There is one site with good evidence of humans living in a milder phase of this cold period. Harnham in Wiltshire was discovered in 2002 during the planning for a ring-road to the south of Salisbury (Bates et al., 2014). Only limited excavations have taken place at the site, but a series of trenches produced several hundred artefacts, including handaxes and flakes from their manufacture (Figures 116 and 117). Although most of the artefacts come from disturbed deposits, they are in fresh condition and refitting of several flakes shows that they have not moved far. It has been suggested that they originate from the underlying floodplain sediments and certainly a few of the artefacts and a handaxe have been found in this deposit.

FIG 116. Handaxe from Harnham. (Francis Wenban-Smith)

The floodplain sands and silts also contain molluscs and occasional mammal remains. The molluscs reflect a mix of habitats from slow-flowing water to marshland and grassland areas. All of the species can be found in Britain today, although the assemblage as a whole hints at cooler conditions, being likened to one of the less cold episodes at the end of the last glaciation. Some of the taxa have quite northern distributions, but the most abundant species is the land gastropod Trichia hispida. This has a distribution that only just reaches the Arctic Circle in the warmer coastal areas of western Norway. The few mammals include horse, bison, mouse and red-backed vole (Clethrionomys). The most interesting species, though, is the Northern Vole, which is found in the boreal and tundra areas of northern Eurasia. The environmental evidence paints a picture of an open floodplain with marshland and grassland, with perhaps some low cover, but little evidence of woodland. Although the climate was not too extreme, conditions were undoubtedly cool.

FIG 117. Refitting flakes from Harnham. (Francis Wenban-Smith)

How humans survived these conditions, we simply do not know. Were they just summer visitors from warmer areas to the south, or were they a relict population from the Purfleet Interglacial? One of the intriguing aspects is their use of handaxes rather than the new Levallois methods of tool-making that had already made an appearance at Purfleet and were to become the favoured tools in the following warm period. The ring-road eventually took a different route, so the site still survives beneath a ploughed field, ripe for further work to answer these questions.

NEANDERTHALS AND THE AVELEY INTERGLACIAL

The following warm period of Stage 7 was once termed the ‘Ilford Interglacial’ after the suburb in northeast London, although now it is more commonly termed the ‘Aveley Interglacial’ (Wymer, 1985; Stringer, 2005). One of the reasons for the original name was a distinctive form of mammoth that was first discovered as part of large collections of mammalian remains from the clay pits near Ilford in Essex. In May 1824 the Gentleman’s Magazine reported the recovery of a virtually complete mammoth:

It lay buried at the depth of about sixteen feet, in a large quarry of diluvian loam and clay which is excavating for making bricks. Mr. John Gibson, of Stratford, has been diligently exerting himself in collecting and preserving as much as possible of this skeleton; and a few days since he invited Professor Buckland and Mr. Cliff to assist him in disinterring the remainder of the bones which he had purposely left in their natural position in the quarry. These gentlemen found a large tusk and several of the largest cylindrical bones of the legs, also many ribs and vertebrae, with the smallest bones of the feet and tail lying close upon one another, so that there can be no doubt, that with those before collected by Mr. Gibson, they had made up an entire skeleton, at least fifteen feet high. (Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, May 1824, 94, p. 454)

This was just the first of many subsequent discoveries in Ilford. Its taxonomic status has long been debated, attributed to steppe mammoth by some and to woolly mammoth by others (Scott, 2007). Whatever its status, it is characterised by being distinctly smaller in form than its cousins and with fewer plates forming the molars.

This type of mammoth has also been found at Aveley, 12 km to the southeast of Ilford, lying on a terrace of the Thames. Sandy Lane was still an active quarry in 1964 when amateur geologist, John Hesketh, discovered mammalian bones in clays at the edge of the pit. The discovery led to excavations by Tony Sutcliffe of the Natural History Museum (West, 1969; Schreve, 2001). The clays were part of a long channel fill with organic muds at the top, containing a rich fauna. Of particular note was the discovery of straight-tusked elephant towards the top of the clays, but Ilford-type mammoth just 30 cm higher in the organic muds. Other herbivores that were recovered through this and subsequent excavations include aurochs, bison, horse, Red Deer and narrow-nosed rhinoceros together with the carnivores of Grey Wolf, Brown Bear (Ursus arctos), Lion and a new species for Britain, Jungle Cat (Felis chaus). The recovery of straight-tusked elephant from below the Ilford mammoth is matched by other distinctions in the faunas, with more grassland taxa such as horse and bison associated with the mammoth. This may show a change from woodland to more open conditions.

The pollen also reflects a shift in the vegetation. The clays were associated with woodland of oak, pine and hazel with occasional lime, hornbeam and spruce. Towards the top of the sequence the hazel and oak declined at the expense of hornbeam and the slight increase in pine, birch, willow and alder. Alongside these changes, there is an increase in open-ground taxa, particularly the grasses of Artemisia, Ribwort Plantain (Plantago lanceolata) and Gramineae. The change to open conditions may simply reflect a shift in the local environment from a flowing river, fringed by woodland, to a choked channel on a wider floodplain with fen and marsh. It is unlikely to indicate a major retreat of forest or a downturn in climate.

So what of the humans? In fact only a handful of artefacts were found at Aveley, but much larger assemblages were recovered from several sites in London that date to the interglacial of that name and are also associated with the Ilford mammoth. If humans were only occasional visitors in Stage 8, they were back with a vengeance at the beginning of the Aveley Interglacial.

Ebbsfleet

If you travel on Eurostar from St Pancras Station towards the Channel Tunnel you pass through Ebbsfleet International just to the south of the Thames. Up to the right you will see areas of former pits, some with landfill, and isolated electricity pylons astride islands of intact sediment. The islands retain some of the few remaining deposits of the Ebbsfleet Channel, a former south-bank tributary of the River Thames (Figure 118). Sometime prior to 1911 the site was first known as ‘Baker’s Hole’ and that name is still retained in much of the literature. The story goes that after a drunken night in a nearby hostelry, a man named Baker fell down one of the large gravel pits in the area. What became of Baker we do not know and little did he realise that he was to give his name to one of the most famous Levallois sites around the world.

FIG 118. Island of the Ebbsfleet Channel sediments surrounded by the quarried areas. (John Wymer)

The pit first came to wider attention in 1911 when Reginald Smith of the British Museum visited to negotiate the transfer by the Associated Portland Cement Company to the British Museum of a large number of unusual flint artefacts (Smith, 1911a). The exceptionally large cores show the careful preparation of the sides and surface to predetermine the shape of the final removals. The resulting flakes usually have an all-round cutting edge and in the larger examples superficially resemble handaxes, but with a very different technology (Figure 115). As long as the quarrying lasted, collectors, archaeologists and geologists continued to recover artefacts and record the geological sections in the area. The most significant collections were those during the 1930s from Major J. P. T. Burchell who wrote a series of papers on the sediments infilling the Ebbsfleet Channel and it was subsequently the focus of British Museum excavations from 1965 to 1970 (Figure 119; Burchell, 1933, 1936; Kerney & Sieveking, 1977; Scott et al., 2010). The most recent work has been an extensive programme of excavation prior to the construction of Ebbsfleet International and the Eurostar line (Wenban-Smith, in press).

FIG 119. In situ Levallois flake at Ebbsfleet. (John Wymer)

The main Levallois artefacts came from a series of deposits in the lower units of the Ebbsfleet Channel. The channel was carved through chalk bedrock while climate was still cool at the beginning of the interglacial, creating a wealth of chalk and flint debris. This ‘coombe rock’ provided ideal raw material and it was certainly used as the majority of the classic Baker’s Hole Levallois artefacts were recovered from this unit. Humans had clearly arrived very early in the interglacial. The overlying sediments are a series of loams and gravels, which were laid down by the Ebbsfleet River and contained similar artefacts. Some environmental evidence has been recovered from the loams and gravels with the Ilford-type mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, horse and Norway Lemming. Together they suggest an open steppe environment, but under reasonably temperate conditions; the molluscs were dominated by the freshwater gastropod Bithynia tentaculata, which today is widespread in most regions of Europe, but tends not to survive further north than southern Scandinavia.

The middle and upper parts of the channel fill show a series of beds suggesting a change of climate to cool, warm and then back to cool conditions. The middle beds are slope deposits, including solifluction, probably laid down under a cool climate. There are no vertebrates, but the molluscs are dominated by the land snail, Pupilla muscorum, which prefers open, sandy conditions and is widespread through southern and northern Europe. A return to warmer conditions is shown by the fauna from the floodplain sediments of the ‘Temperate Bed’. The mammals include giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus), steppe mammoth and horse. The molluscs are predominantly aquatic species, such as Galba truncatula and Anisus leucostama that inhabit small, stagnant pools or the muddy areas of floodplains, while Anisus vortex and Bathyomphalus contortus prefer well-oxygenated water. The uppermost beds see a return to cool conditions with further slope deposits.

The marine isotope record for the Aveley Interglacial is complex with a series of peaks and troughs divided into Substages 7e to 7a. It is tempting to attribute the lower loams and gravels to Substage 7e with the later substages shown by the alternating cool and warm conditions of the middle and upper beds. This may prove to be the case, but the recent excavations promise to show in more detail deposits that relate to the later parts of Stage 7 (Wenban-Smith, in press). Although the middle and upper beds contain flint artefacts, they all seem to be derived from older deposits on the surrounding slopes, and date to an earlier period. There are no contemporary artefacts with the middle and upper channel beds. Were humans absent from the later substages of the Aveley Interglacial? This is a question that we will return to at the end of the chapter, but meanwhile what are the other sites with human evidence?

Crayford

Some 9 km to the west of Ebbsfleet lie the London suburbs of Erith, Slade Green and Crayford. In the latter half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries the area was dominated by large brickearth pits with silts and clays laid down by the Thames that provided bricks for the expansion of London. Nearby in the neighbouring suburb of Belvedere was the home of Flaxman C. J. Spurrell, one of the most remarkable amateur prehistorians of the nineteenth century (Scott & Shaw, 2009). His enthusiasm for early prehistory and indeed natural history stemmed from his father, a medical practitioner, who had grown up in the rich fossil-hunting areas near Cromer. Both father and son were members of a variety of societies including the West Kent Natural History Society, the Kent Archaeological Society and the Essex Field Club. Unlike his father, Spurrell was essentially a gentleman of leisure, having an inheritance from his maternal grandfather. This gave him the time to scour the pits of the area, in particular those around Crayford.

FIG 120. Photograph by Flaxman Spurrell at Stoneham’s Pit, Crayford. The man in front of the section bears a resemblance to Flaxman and might be his brother.

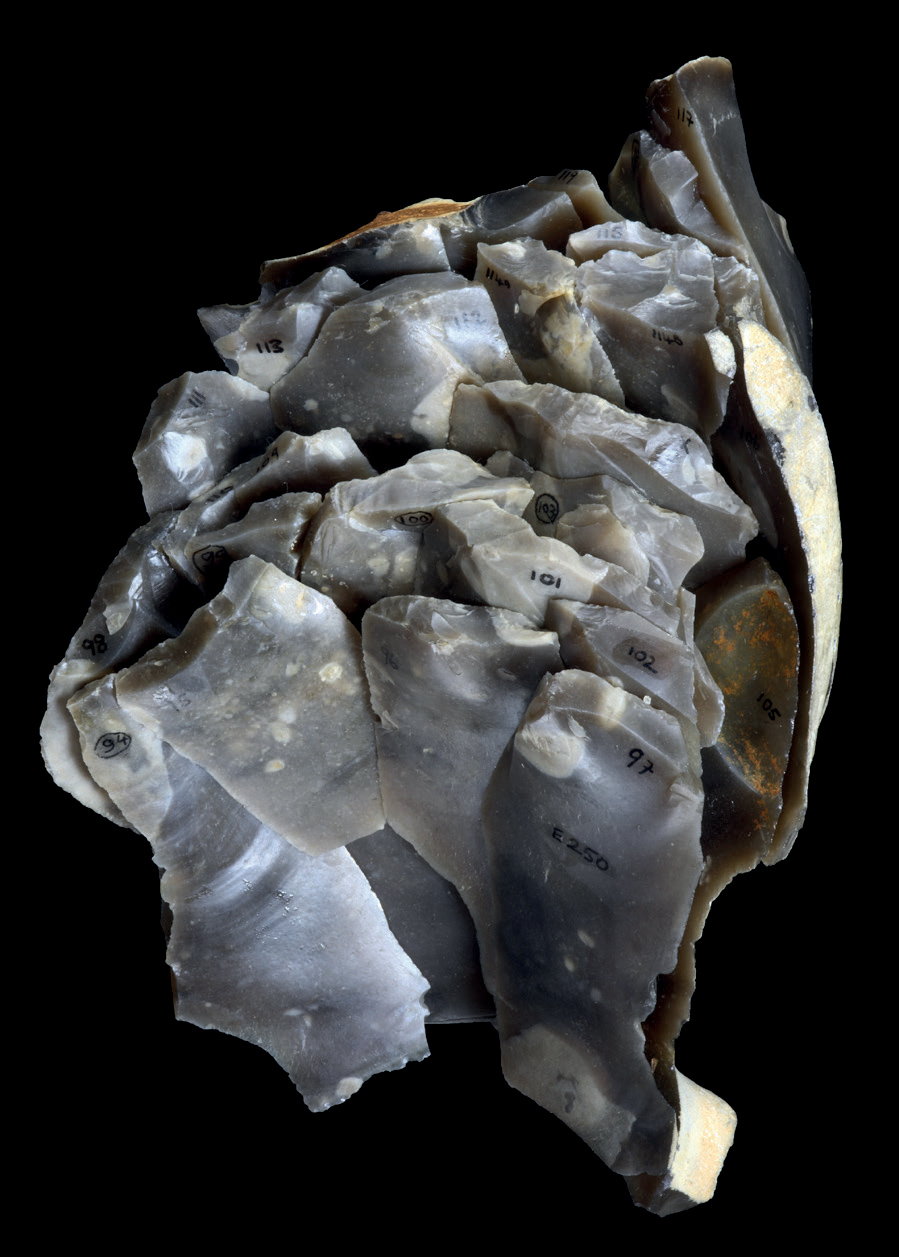

On the 4 March 1880 Spurrell made an exceptional discovery – an in situ flint knapping floor in brickearth, beneath a chalk cliff on the edge of Stoneham’s Pit (Figure 120; Spurrell, 1880a, 1880b). The discovery of the find was only equalled by Spurrell’s meticulous recording and his recognition of its significance. He immediately wrote to his long-time friend the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, who was less impressed than one of the first visitors, Sir John Evans. Spurrell quickly realised that many of the pieces refitted into large clusters of elongated flakes, occasionally going back on to their core (Figure 121). This was not only the first time that anyone had attempted refitting, but it also led him to explore new avenues of research such as experimental knapping to understand the technology and give serious consideration to how artefacts moved naturally after discard. These were the very first insights into the processes behind the archaeological record. As with many exceptional men he was a shy and retiring individual, who published little on his work, and it was many decades later that his ideas were fully embraced by professional archaeology.

FIG 121. Refitting flakes, blades and Levallois point from Crayford. (Courtesy of the Natural History Museum)

The refitting flakes provide an excellent example of Levallois technology on elongated nodules. The refitting shows that the desired end-products, rather than being flakes, were actually Levallois points. Being a manufacturing area, there are very few associated with the knapping floor, so presumably they were taken away and used elsewhere.

Spurrell also collected some of the mammalian bones from the brickearth, but as the remains probably came from various depths they seem to form a mixed assemblage. Although there is one example of a Musk Ox, the majority of taxa are consistent with open grassland in a temperate climate, similar to the lower levels at Ebbsfleet. They include Ilford mammoth, narrow-nosed rhinoceros, woolly rhinoceros, horse and Ground Squirrel. The molluscs show that the brickearths were laid down under slow-flowing water in a warm climate with the most common taxa being the freshwater clam, Corbicula fluminalis, together with the freshwater mussels, Unio and Anodonta (Kennard, 1944). Frequently they were found articulated, suggesting that they were contemporary with the deposit.

The picture that emerges from Crayford is of a large, flat floodplain in a backwater of the slow-flowing Thames (Figure 122). Both the floodplain and higher ground beyond were open steppe with a few stands of woodland, grazed by rhinoceros, mammoth and horse. On the edge of the plain, the river had carved a low cliff through chalk and at its base lay freshly eroded chalk rubble and flint nodules. People visited briefly, selecting elongated nodules, which were carefully flaked in preparation for final pointed removals. The scatters of flint waste were left behind, but the pointed flakes were collected and taken away. The next flood gently covered the flint scatters in silt, burying them until rediscovery some 250,000 years later. But where were the points taken and how were they used? Some of the answers to this question lie upstream at the site of Creffield Road in Acton.

FIG 122. Reconstruction of Crayford. (Craig Williams)

Creffield Road and West London

Creffield Road runs through a leafy suburb of west London, where Victorian houses stand back from tree-lined streets. If Crayford benefited from the endeavours of Spurrell and Stoke Newington was blessed with Worthington Smith, then Acton was rewarded with John Allen Brown. Like his father, he was a diamond merchant by trade, commuting daily to Hatton Garden in London. His passion though was Palaeolithic archaeology. As the houses were being built along Creffield Road, small pits were dug at the rear of the properties for sand and gravel for their construction. Brown’s frequent visits led to the recovery of hundreds of artefacts from various pits, but the pits behind 83 Creffield Road proved to be particularly rich (Brown, 1887; Scott, 2011). Due to his meticulous records it is known that the majority of the flint tools came from a single horizon at the base of silts immediately above the Lynch Hill Gravel of the Thames. The position of the artefacts on the surface of the gravel suggests that the site dates to an early part of the Aveley Interglacial, after the river had cut down to a lower course. Unfortunately no bone or other environmental evidence survives, so all that is known is that the site would have looked down over the floodplain of the Thames, a few hundred metres to the south. Similar flint artefacts were also collected by Brown on the surface of the Lynch Hill Gravel in many of the large gravel pits to the west of Creffield Road, in the boroughs of West Drayton and Yiewsley (Figures 123 and 124).

The stone tools are all made of local flint and consist of flakes from initial preparation of Levallois cores, several highly reduced cores and a series of Levallois points, often broken (Scott, 2011). The interesting aspect is the lack of flakes from the middle stages of the knapping process, suggesting that it was a location for initial core preparation, but then the semi-prepared cores were taken elsewhere for the production and presumably use of Levallois points. On returning to the site, the humans brought back the highly reduced cores and Levallois points, some of which had been damaged through use. At Creffield Road we can begin to see how humans were using the broader landscape from initial tool acquisition at the site, leaving for a hunting expedition and then returning to re-equip or repair damaged tools.

FIG 123. Abandoned pit at Yiewsley. (John Wymer)

FIG 124. Levallois point from Yiewsley. (Beccy Scott; courtesy of Museum of London)

Perhaps a more important aspect is how the tools were used. The Levallois points from Creffield Road and from nearby sites in Yiewsley are all carefully crafted and some have a series of small removals at their base. Their design suggests that they were hafted onto a shaft to make flint-tipped spears (Figure 124). If this is the case, then it is the earliest example of a ‘composite tool’, where the working part of the tool is given a handle. Although this is a simple concept and one that we take for granted, its introduction gave improved grip, better leverage and increased power. It was eventually to transform tool use. If people’s daily routines were encompassing a broader swathe of landscape, how far did this take them? We get hints of this from 40 km to the north at Caddington.

Caddington

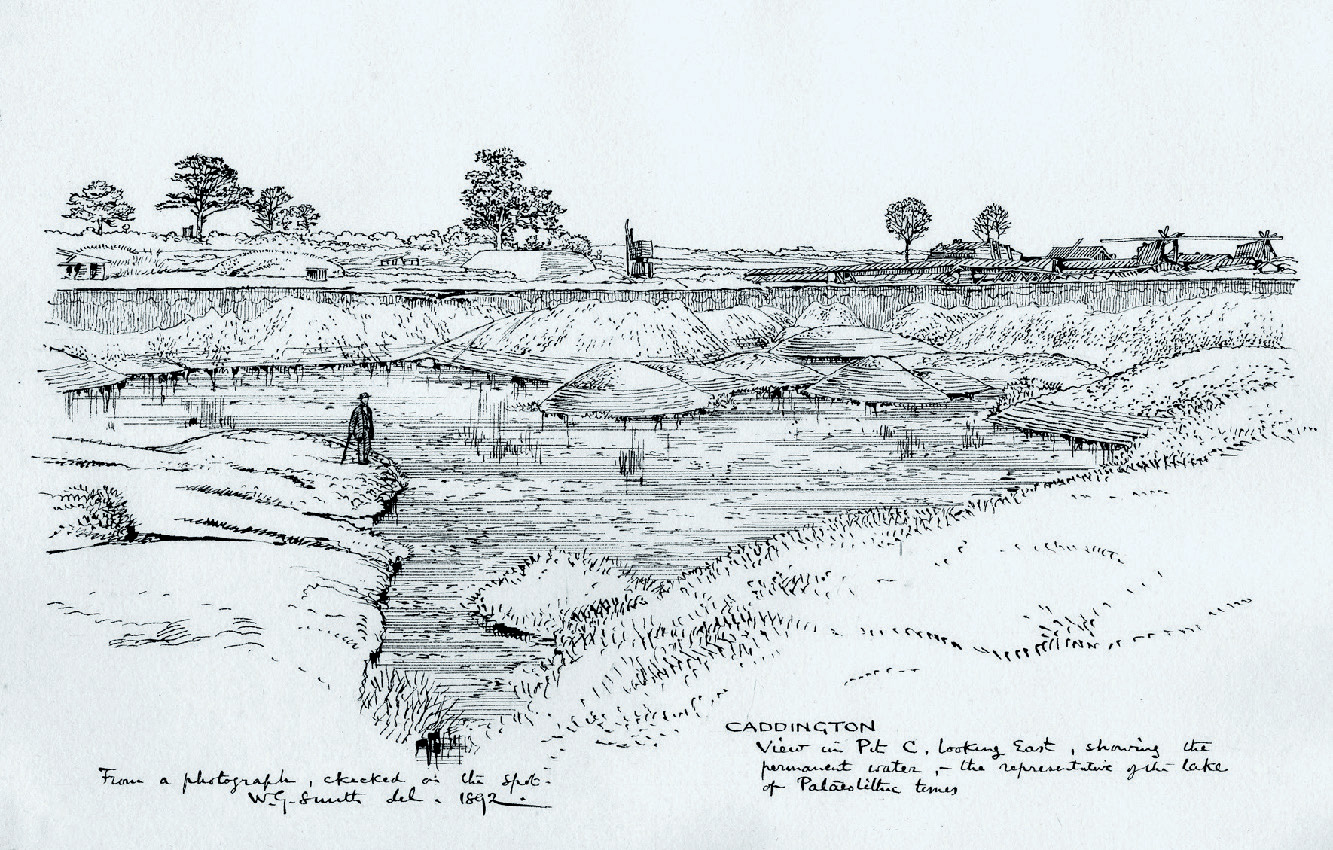

In 1885 Worthington Smith moved from London and his handaxe hunting grounds of Stoke Newington to the market town of Dunstable in Bedfordshire. The reason was heart problems. If his doctor had asked him to slow down, he clearly did not take the advice, but enjoyed the full benefits of the country air, regularly walking miles across the nearby Dunstable Downs. In doing so he encountered a series of small clay pits that were being dug to make bricks, in particular around the village of Caddington (Figure 125; Smith, 1894). He was soon recovering flint artefacts from the clays, many of which were in sharp condition. He was very aware of the refitting work of Spurrell, and the next few years were spent recovering artefacts and often conjoining them back together. Many of the pits contained handaxes and flakes from their manufacture, but from 1903 to 1906 one clay pit produced a series of Levallois artefacts (Bradley & Sampson, 1978).

FIG 125. Pit at Caddington illustrated by Worthington Smith. (Courtesy of Luton Museum)

The pits were exploiting pockets of clay that were the infillings of solution hollows in the underlying chalk. As the chalk dissolved, hollows formed and small ponds developed, gradually infilling with silt and clay. It is around the edges of the ponds that humans gathered flint that had eroded from the chalk and made their tools. Unfortunately no biological remains survive, so the sites are difficult to date and little is known about the contemporary environment. We can, though, hazard a guess (Ashton et al., 2006). As isolated ponds on downland hilltops they would have been difficult to find in dense forest, but in open conditions they would have been more obvious features of the landscape. Bare hilltops would also have provided the necessary conditions for exposing chalk and eroding flint through wind and rain. Not only would the small ponds have provided fresh water and flint, but they would have been ideal viewing points over the valleys below for tracking herds of deer, horse, bison, rhinoceros and mammoth. For the sites to have been a focus for people, we have to imagine an open steppe landscape, dissected by valleys teeming with game.

Worthington Smith continued his researches around Dunstable, discovering sites such as Gaddesden Row, Round Green and Whipsnade until his death in 1917. He died in characteristic style with one walk too many. Eager to record and photograph the damage from an aerial torpedo from a German Zeppelin near the Harrison Carter Engineering works in Dunstable, he caught a chill and died only a week later. With his collections, meticulous notes and publications he stands out as one of the greats of Palaeolithic archaeology.

Pontnewydd Cave

So far nearly all the early Neanderthal sites have been in southeast England, with a particular concentration in the Thames Valley. To some extent this does seem to be a real boundary to their territory, with very few sites further west or north. But there is major exception – Pontnewydd Cave in North Wales (Aldhouse-Green et al., 2012).

Pontnewydd is one of the Cefn Caves that lie above the River Elwy in Denbighshire (Figure 126). For centuries the caves had been the subject of Welsh legend and had been remarked upon by various writers. The old road heading south winds along the limestone valley and was described by Thomas Pennant as having ‘most romantic dingles, varied with meadows, woods and cavernous rocks. Neither is destitute of antiquities’ (Pennant, 1781). The caves were visited by many geologists and antiquarians during the nineteenth century, but one of the earlier visitors in 1831 was a youthful Charles Darwin, accompanied by the Professor of Geology at Cambridge, Adam Sedgwick. It was a trip that seems to have helped steer Darwin’s future path as in a letter to Sedgwick in 1873 he wrote, ‘I am pleased that you remember my attending you in your excursions in 1831. To me it was a memorable event in my life: I felt it a great honour, and it stimulated me to work, and made me appreciate the noble science of geology’ (Aldhouse-Green et al., 2012).

FIG 126. Entrance to Pontnewydd Cave. (© National Museum of Wales)

Doubtless the local populace were oblivious to the significance of Darwin’s visit, but paid far more attention a few decades later to the ‘4 ft 7 in’ lizard that was reported in the Flintshire Observer on 4 November 1870. The lizard, likened to a crocodile, had been slain by chimney sweep, Thomas Hughes. The enterprising Hughes had in fact bought it from a travelling menagerie, already dead, but displayed it as the ‘marvellous lizard of Cefn’.

More serious work soon followed. Although there had been earlier research on the other Cefn Caves, the first investigations at Pontnewydd were in the early 1870s, initially by Boyd Dawkins and then by McKenny Hughes, successor to Sedgwick at Cambridge, resulting in the cave becoming involved in many of the debates about antediluvian and pre-glacial man (see Chapter 2). Little major work was undertaken for over a century until the large-scale excavations by Stephen Green of the National Museum of Wales from 1978 to 1995 (Green, 1984; Aldhouse-Green et al., 2012).

The main entrance to the cave is 15 m above the river and is about 3 m in height with a similar width and extends back at least 30 m, while a smaller side-entrance was discovered in 1987 buried under 6 m of scree. The fill of the cave is complex, but the main sediments to produce artefacts and fauna were a series of debris flows, the top of which became cemented as breccia. The debris flows imply some transport and possible intermixing of different faunal and artefact assemblages, although their condition suggests comparatively little movement. The breccia has been dated to 230,000 years ago, which gives a minimum age for the fauna and stone tools.

For the vertebrates an assemblage has been isolated based on the similarity in condition. Merck’s rhinoceros and narrow-nosed rhinoceros are the only large herbivores, but they are accompanied by Red Deer, Roe Deer, horse and European Beaver. The smaller mammals suggest cool, open conditions with Mountain Hare, Northern Vole, Norway Lemming and Arctic Lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus). Competition for the cave may have been fierce with Wolf, Leopard (Panthera pardus), Lion and bear. Possible cut marks on the bear bones suggest skinning, so it would seem that the bear came off second best. Hibernating bears would have been comparatively easy prey for the Neanderthals and provided not only meat, but thick skins for warmth.

The only other faunal remains are from bird bones, with Brent Goose (Branta bernicla), Mallard (Anas platyrhyncos), Common Scoter (Melanitta nigra), Goosander (Mergus merganser) and Wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe). The goose and various ducks would have thrived on the nearby Elwy River, while the Wheatear would have preferred open, dry country nesting in the rock crevices around the cave.

There are over a thousand stone tools from the various excavations made on a mix of different raw materials with flint, rhyolite and a variety of tuffs, most of which were available in the nearby stream bed. As would be expected for this period many of the artefacts are Levallois cores and flakes, but out of keeping with sites in southeast England, there are also handaxes (Figure 127). It is not really known whether the two tool types were made by the same people and the most recent work suggests that two different groups of humans were involved. But who were the people?

FIG 127. Handaxe showing opposite faces from Pontnewydd Cave. (© National Museum of Wales)

Pontnewydd is the only Middle Palaeolithic site in Britain to produce human remains, with a total of 17 Neanderthal teeth and a fragment of maxilla (Figure 128; Stringer, 1984, 2012; Compton & Stringer, 2012a). The teeth show a feature called ‘taurodontism’ where the pulp cavity and size of the molars is enlarged at the expense of the roots. This is a characteristic of Neanderthals, which may have helped increase the chewing life of the teeth. Microscopic analysis of the tooth surfaces shows wear characteristic of tough, fibrous plant foods, suggesting that meat was not the main part of their diet. In several examples there are cut marks showing that the teeth were used as a grip while cutting food.

FIG 128. Human jaw from Pontnewydd Cave. (© National Museum of Wales)

The teeth also provide clues to the age and sex of the group. There are at least five individuals, with the maxilla with two teeth being from a 9-year-old girl. The other teeth are probably from three boys, aged 8, 11 and 14–16, and one adult male. It is clear that the young girl did not survive beyond the age of 9, but the close proximity and condition of the other teeth also suggest that they reflect age at death, rather than tooth loss; the jaws and bones have simply not survived. Several teeth show hypoplasia, with underdevelopment indicative of disease or starvation. One curious aspect is the apparent imbalance between the genders, which does not seem to reflect a family group. If the teeth are representative of the occupants, was the group a hunting or foraging party that was passing through, rather than using the cave as a home base? The number and range of stone tools would suggest not, with the cave occupied for significant lengths of time by successive family groups.

The Elwy Valley and surrounding hills have probably changed very little since Pontnewydd was first occupied over 230,000 years ago, so it is easy to imagine this secluded valley being home to several generations of Neanderthals. The cave provided a base with protection from the cold and from the lions, leopards, wolves and bears that roamed the hills. It would have made a good look-out post for spotting game in the valley below, inhabited by deer, horse and rhinoceros. The tumbling river provided fresh water and its pebble bed gave a variety of rocks for making stone tools. It also supported duck and geese, which might have contributed to the human diet. Beyond the valley the open hills rose to over 200 m before dropping to the next valley. The dissected landscape gave a variety of habitats to the people, with only short distances between hill-top and valley resources. It seems an idyllic spot, but life would have been tough, particularly during the long, cold winters. At some point tragedy struck with the premature death of several group members. Disease or starvation may have been the cause, so were they the last struggling survivors of an isolated population on the northwestern frontier of the Neanderthal world? A dwindling population also seems to be the case for the rest of Britain with growing evidence that the initial incursion by people during this interglacial was short-lived; there is little, if any, evidence of humans in the later parts of this stage.

LATER IN THE AVELEY INTERGLACIAL – MARSWORTH

On the northern scarp slope of the Chilterns overlooking the Vale of Aylesbury a former chalk pit is now home to College Lake Wildlife Centre, just east of the village of Marsworth. Two channels have been described over the last few decades, the lower of which dates to the Aveley Interglacial of Stage 7 (Green et al., 1984; Murton et al., 2001, 2015). The Lower Channel is filled with river-laid gravelly sand with bone and large blocks of tufa, which probably formed from a nearby spring (Figure 129). This bed is overlain by patches of organic mud and then covered by hill-wash of chalky mud, sand and gravel.

FIG 129. In situ mammal bones from the channel deposits at Marsworth. (© David Parish/Buckinghamshire County Museum)

The sequence includes a wide range of biological remains that may cover the full interglacial. Several different environments can be described, the oldest of which is from the tufa. This formed as a calcareous precipitate from a spring on the edge of the scarp slope of the chalk and was subsequently fragmented and reworked into the stream bed. The tufa contains terrestrial molluscs that prefer a wooded, temperate climate such as Discus rotundatus and Azeca goodalli. Frog bones also survive, but more useful are the fossilised plants and their impressions. Calcified bryophyte cushions show mosses, while leaf impressions from willow, maple and Mountain-ash (Sorbus aucuparia) support the evidence from the molluscs of a wooded, temperate environment. To this can be added the pollen, which shows ash and pine with occasional oak, birch, hornbeam and hazel. Other blocks of tufa paint a slightly different picture, where the pollen is dominated by grasses and herbs. This has been interpreted as showing localised grassland areas, kept open by grazing herbivores (Murton et al., 2001). Trampling is suggested to have caused the break-up of the tufa. An alternative interpretation comes from more recent dating working using Uranium-series. Two clusters of dates on the tufa of around 240,000 and 210,000 years ago show that it formed in two separate phases (Candy & Schreve, 2007), so perhaps there were differences in the vegetation of the phases, one being more wooded than the other.

Either way both sets of tufa pre-date the stream in which they eventually came to rest. The sandy gravel and the organic mud also contain plant remains, shells, beetles and mammals, all indicative of more open conditions. The plants show that the channel was filled with shallow, slow-flowing or still water supporting waterlillies, frogbit (Hydrochara) and duckweed. The water edge was fringed by sedges, Bulrush, rushes (Juncus) and Cursed Buttercup, while disturbed, sometimes stony, grassland is shown by Common Whitlow-grass (Erophila verna), varieties of the mustard family (Cruciferae) and violets (Viola). Trees were rare with stands of birch, alder and willow with occasional poplar, oak, elm, yew and hornbeam. Taller shrubs such as hazel and Redcurrant (Ribes rubrum) added to the vegetation. The molluscs also indicate marsh, grassland and bare ground as shown by Pupilla muscorum and Trichia hispida, with an increase in grassland taxa towards the top of the channel.

The 92 beetle taxa from the organic mud show a similar picture, with swamp and grassland species and none that are dependent on trees. Cool conditions are suggested by Simplocaria metallica and Pycnoglypta lurida with current distributions in Scandinavia and northern Poland. Average temperatures are estimated as 15°C in July and −5°C in January. Of note are the dung beetles (Aphodius), reflecting the presence of large mammals. They were undoubtedly around as shown by the bones, teeth and ivory from the Ilford type of mammoth, straight-tusked elephant, narrow-nosed rhinoceros, aurochs, bison, horse and Red Deer. Together with a range of voles and shrews, Northern Vole also suggests cooler conditions. The herbivores were preyed on by Brown Bear, Lion, Wolf and Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes). This fauna is typical of the open, mammoth steppe. But missing from this fauna are humans. As a spring-side location on the Chilterns overlooking the Vale of Aylesbury to the north you would have thought that it would be an ideal location for spotting passing game. But were they in Britain at this time? To help answer this question, we have to work out when exactly Marsworth dates within Stage 7.

At Marsworth at least three different environmental episodes can be identified, with two phases of temperate woodland and grassland vegetation, followed by a phase of cooler, open steppe. It has been suggested that these changes in environment cover a large part of Stage 7. As discussed above, this stage has been subdivided into five substages (7e to 7a) with three warm peaks and two cooler troughs. At Marsworth the earlier temperate phases are thought to be 7e and 7c and the cooler phase 7b (Candy & Schreve, 2007). This may be the case, but of importance is the presence of hornbeam throughout the sequence. This tree was always late in arriving after peak interglacial conditions had become established, colonising from refugia in the Carpathians in southeast Europe. Another late arrival in most interglacials was the terrestrial mollusc Discus rotundatus. Its presence and that of hornbeam suggests that we are missing the earliest part of Stage 7, perhaps just the first few thousand years of substage 7e. But it was these first few thousand years that saw evidence of humans at Ebbsfleet, and possibly Creffield Road and Pontnewydd. Does this mean that people were only in Britain for the first part of the Aveley Interglacial? So far the evidence would suggest this is the case, but more well-dated sites are needed to properly test this idea.

NEANDERTHALS AND THE MAMMOTH STEPPE

The Purfleet and Aveley interglacials witness a period of transition, both in the changing environments of temperate climates in Britain, but also in the development of Neanderthals and how they used those landscapes. The environments of the Purfleet Interglacial seem little different from those of the Hoxnian with mixed deciduous forest dominating the landscape in all but the more open grasslands of the river valleys. Populating these landscapes were species indicative of woodland, such as European Beaver, Macaque, Fallow and Roe Deer, together with straight-tusked elephant. Horse and bison suggest more open grazing.

By contrast, the Aveley Interglacial shows more open landscapes with the Ilford mammoth, steppe mammoth, narrow-nosed rhinoceros, woolly rhinoceros, horse, bison and aurochs. These are creatures of what has become known as the ‘Mammoth-Steppe’ (Guthrie, 1990). The steppe landscapes first developed in eastern Eurasia, but by 300,000 years ago they expanded into central and western Europe. Why this happened is not known, but may relate to changes in climate, with cooler winters and less precipitation. The effect was that by 250,000 years ago the steppes reached Britain with its large herds of mammoth, rhinoceros, bison and horse.

Not only were the landscapes changing, but so too were Neanderthals. When they returned to Britain at the beginning of the Aveley Interglacial they were already adapted to these new landscapes. The open steppes supported larger, more visible herds and with knowledge of their movements and migrations would have provided more predictable opportunities for Neanderthal hunters. Larger areas of the landscape could now be exploited with greater distances traversed. No longer was hunting and scavenging limited to the river valleys, but also now extended into the grassland plateaux and plains above.

The exploitation of larger herds would have required bigger hunting groups, greater cooperation between hunters and more efficient tool kits. Hafted Levallois points provided more effective spears for maiming and killing the captured game. While Ebbsfleet and Crayford show where these tools were made, Creffield Road provides a glimpse of how base camps were established to make and repair the tools. The use of more upland areas is shown by Caddington.

Bigger hunting groups and the use of wider territories must have had an effect on how these Neanderthal societies operated. Increased group size required better mechanisms for dealing with relationships between group members and potential conflict. Larger territories could have led to more specialised subgroups spending days away from the main base to re-provision the group with meat or other resources. Although we can only guess at how these early Neanderthal societies operated, there must have been a shift in behaviour in the open steppes of the Aveley Interglacial from those of earlier periods and the Purfleet Interglacial.

Occupation of Britain, though, seems to have been short-lived, with the only good evidence from the first few thousand years of the Aveley Interglacial, where populations seem to have been concentrated in the Thames Valley. Forays beyond southeast England clearly occurred, as shown by the evidence from Pontnewydd in North Wales. But this population seems to have come to an untimely end on the edge of the Neanderthal world. Why then was occupation so brief? One answer might be that they first arrived in Britain in the early interglacial while sea-levels were still low, expanding their territories alongside that of the mammoth steppe. With the rise in sea-level, isolation from mainland Europe would have cut off gene flow into Britain on the margins of the Neanderthal range. At least some of the hunters of Pontnewydd were suffering from disease, with premature death. Was this also the case for other populations to the south? Unfortunately we do not know, but it does seem that Neanderthals only survived for the first few thousand years of the Aveley Interglacial.

The popular image of Neanderthals is less than complimentary, often caricatured as bumbling idiots, the butt of many a cartoon joke or film and even used as a term of abuse. As we can see from the evidence above, the reality is very different. They were beginning to develop more specialised hunting, use larger territories and adapting successfully to new open landscapes. The reason they seemed to have struggled in Britain may only have been because of isolation from mainland Europe and with insufficient numbers to maintain a viable population. However, they were to return, but not for over 150,000 years. The combination of cold climate, followed by high sea-levels prevented occupation. When they did return, some 60,000 years ago, they had the means to survive far more harsh environments.