Somewhere in Steinbeck country two tired men sit down at the side of the road. Lenny combs his beard with his fingers and says, “Tell me about the laws of physics, George.” George looks down for a moment, then peers at Lenny over the tops of his glasses. “Okay, Lenny, but just the minimum.”

The term classical physics refers to physics before the advent of quantum mechanics. Classical physics includes Newton’s equations for the motion of particles, the Maxwell-Faraday theory of electromagnetic fields, and Einstein’s general theory of relativity. But it is more than just specific theories of specific phenomena; it is a set of principles and rules—an underlying logic—that governs all phenomena for which quantum uncertainty is not important. Those general rules are called classical mechanics.

The job of classical mechanics is to predict the future. The great eighteenth-century physicist Pierre-Simon Laplace laid it out in a famous quote:

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.

In classical physics, if you know everything about a system at some instant of time, and you also know the equations that govern how the system changes, then you can predict the future. That’s what we mean when we say that the classical laws of physics are deterministic. If we can say the same thing, but with the past and future reversed, then the same equations tell you everything about the past. Such a system is called reversible.

A collection of objects—particles, fields, waves, or whatever—is called a system. A system that is either the entire universe or is so isolated from everything else that it behaves as if nothing else exists is a closed system.

Exercise 1: Since the notion is so important to theoretical physics, think about what a closed system is and speculate on whether closed systems can actually exist. What assumptions are implicit in establishing a closed system? What is an open system?

To get an idea of what deterministic and reversible mean, we are going to begin with some extremely simple closed systems. They are much simpler than the things we usually study in physics, but they satisfy rules that are rudimentary versions of the laws of classical mechanics. We begin with an example that is so simple it is trivial. Imagine an abstract object that has only one state. We could think of it as a coin glued to the table—forever showing heads. In physics jargon, the collection of all states occupied by a system is its space of states, or, more simply, its state-space. The state-space is not ordinary space; it’s a mathematical set whose elements label the possible states of the system. Here the state-space consists of a single point—namely Heads (or just H)—because the system has only one state. Predicting the future of this system is extremely simple: Nothing ever happens and the outcome of any observation is always H.

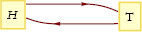

The next simplest system has a state-space consisting of two points; in this case we have one abstract object and two possible states. Imagine a coin that can be either Heads or Tails (H or T). See Figure 1.

Figure 1: The space of two states.

In classical mechanics we assume that systems evolve smoothly, without any jumps or interruptions. Such behavior is said to be continuous. Obviously you cannot move between Heads and Tails smoothly. Moving, in this case, necessarily occurs in discrete jumps. So let’s assume that time comes in discrete steps labeled by integers. A world whose evolution is discrete could be called stroboscopic.

A system that changes with time is called a dynamical system. A dynamical system consists of more than a space of states. It also entails a law of motion, or dynamical law. The dynamical law is a rule that tells us the next state given the current state.

One very simple dynamical law is that whatever the state at some instant, the next state is the same. In the case of our example, it has two possible histories: H H H H H H . . . and T T T T T T . . . .

Another dynamical law dictates that whatever the current state, the next state is the opposite. We can make diagrams to illustrate these two laws. Figure 2 illustrates the first law, where the arrow from H goes to H and the arrow from T goes to T. Once again it is easy to predict the future: If you start with H, the system stays H; if you start with T, the system stays T.

Figure 2: A dynamical law for a two-state system.

A diagram for the second possible law is shown in Figure 3, where the arrows lead from H to T and from T to H. You can still predict the future. For example, if you start with H the history will be H T H T H T H T H T . . . . If you start with T the history is T H T H T H T H . . . .

Figure 3: Another dynamical law for a two-state system.

We can even write these dynamical laws in equation form. The variables describing a system are called its degrees of freedom. Our coin has one degree of freedom, which we can denote by the greek letter sigma, σ. Sigma has only two possible values; σ = 1 and σ = −1, respectively, for H and T. We also use a symbol to keep track of the time. When we are considering a continuous evolution in time, we can symbolize it with t. Here we have a discrete evolution and will use n. The state at time n is described by the symbol σ(n), which stands for σ at n. The value of n is a sequence of natural numbers beginning with 1.

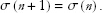

Let’s write equations of evolution for the two laws. The first law says that no change takes place. In equation form,

In other words, whatever the value of σ at the nth step, it will have the same value at the next step.

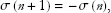

The second equation of evolution has the form

implying that the state flips during each step.

Because in each case the future behavior is completely determined by the initial state, such laws are deterministic. All the basic laws of classical mechanics are deterministic.

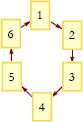

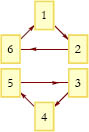

To make things more interesting, let’s generalize the system by increasing the number of states. Instead of a coin, we could use a six-sided die, where we have six possible states (see Figure 4).

Now there are a great many possible laws, and they are not so easy to describe in words—or even in equations. The simplest way is to stick to diagrams such as Figure 5. Figure 5 says that given the numerical state of the die at time n, we increase the state one unit at the next instant n + 1. That works fine until we get to 6, at which point the diagram tells you to go back to 1 and repeat the pattern. Such a pattern that is repeated endlessly is called a cycle. For example, if we start with 3 then the history is 3, 4, 5, 6, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 1, 2, . . . . We’ll call this pattern Dynamical Law 1.

Figure 4: A six-state system.

Figure 5: Dynamical Law 1.

Figure 6 shows another law, Dynamical Law 2. It looks a little messier than the last case, but it’s logically identical—in each case the system endlessly cycles through the six possibilities. If we relabel the states, Dynamical Law 2 becomes identical to Dynamical Law 1.

Not all laws are logically the same. Consider, for example, the law shown in Figure 7. Dynamical Law 3 has two cycles. If you start on one of them, you can’t get to the other. Nevertheless, this law is completely deterministic. Wherever you start, the future is determined. For example, if you start at 2, the history will be 2, 6, 1, 2, 6, 1, . . . and you will never get to 5. If you start at 5 the history is 5, 3, 4, 5, 3, 4, . . . and you will never get to 6.

Figure 6: Dynamical Law 2.

Figure 7: Dynamical Law 3.

Figure 8 shows Dynamical Law 4 with three cycles.

Figure 8: Dynamical Law 4.

It would take a long time to write out all of the possible dynamical laws for a six-state system.

Exercise 2: Can you think of a general way to classify the laws that are possible for a six-state system?

Rules That Are Not Allowed: The Minus-First Law

According to the rules of classical physics, not all laws are legal. It’s not enough for a dynamical law to be deterministic; it must also be reversible.

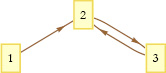

The meaning of reversible—in the context of physics—can be described a few different ways. The most concise description is to say that if you reverse all the arrows, the resulting law is still deterministic. Another way, is to say the laws are deterministic into the past as well as the future. Recall Laplace’s remark, “for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.” Can one conceive of laws that are deterministic into the future, but not into the past? In other words, can we formulate irreversible laws? Indeed we can. Consider Figure 9.

Figure 9: A system that is irreversible.

The law of Figure 9 does tell you, wherever you are, where to go next. If you are at 1, go to 2. If at 2, go to 3. If at 3, go to 2. There is no ambiguity about the future. But the past is a different matter. Suppose you are at 2. Where were you just before that? You could have come from 3 or from 1. The diagram just does not tell you. Even worse, in terms of reversibility, there is no state that leads to 1; state 1 has no past. The law of Figure 9 is irreversible. It illustrates just the kind of situation that is prohibited by the principles of classical physics.

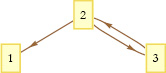

Notice that if you reverse the arrows in Figure 9 to give Figure 10, the corresponding law fails to tell you where to go in the future.

Figure 10: A system that is not deterministic into the future.

There is a very simple rule to tell when a diagram represents a deterministic reversible law. If every state has a single unique arrow leading into it, and a single arrow leading out of it, then it is a legal deterministic reversible law. Here is a slogan: There must be one arrow to tell you where you’re going and one to tell you where you came from.

The rule that dynamical laws must be deterministic and reversible is so central to classical physics that we sometimes forget to mention it when teaching the subject. In fact, it doesn’t even have a name. We could call it the first law, but unfortunately there are already two first laws—Newton’s and the first law of thermodynamics. There is even a zeroth law of thermodynamics. So we have to go back to a minus-first law to gain priority for what is undoubtedly the most fundamental of all physical laws—the conservation of information. The conservation of information is simply the rule that every state has one arrow in and one arrow out. It ensures that you never lose track of where you started.

The conservation of information is not a conventional conservation law. We will return to conservation laws after a digression into systems with infinitely many states.

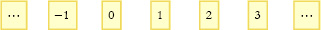

Dynamical Systems with an Infinite Number of States

So far, all our examples have had state-spaces with only a finite number of states. There is no reason why you can’t have a dynamical system with an infinite number of states. For example, imagine a line with an infinite number of discrete points along it—like a train track with an infinite sequence of stations in both directions. Suppose that a marker of some sort can jump from one point to another according to some rule. To describe such a system, we can label the points along the line by integers the same way we labeled the discrete instants of time above. Because we have already used the notation n for the discrete time steps, let’s use an uppercase N for points on the track. A history of the marker would consist of a function N(n), telling you the place along the track N at every time n. A short portion of this state-space is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11: State-space for an infinite system.

A very simple dynamical law for such a system, shown in Figure 12, is to shift the marker one unit in the positive direction at each time step.

Figure 12: A dynamical rule for an infinite system.

This is allowable because each state has one arrow in and one arrow out. We can easily express this rule in the form of an equation.

|

(1) |

Here are some other possible rules, but not all are allowable.

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

Exercise 3: Determine which of the dynamical laws shown in Eq.s (2) through (5) are allowable.

In Eq. (1), wherever you start, you will eventually get to every other point by either going to the future or going to the past. We say that there is a single infinite cycle. With Eq. (3), on the other hand, if you start at an odd value of N, you will never get to an even value, and vice versa. Thus we say there are two infinite cycles.

We can also add qualitatively different states to the system to create more cycles, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13: Breaking an infinite configuration space into finite and infinite cycles.

If we start with a number, then we just keep proceeding through the upper line, as in Figure 12. On the other hand, if we start at A or B, then we cycle between them. Thus we can have mixtures where we cycle around in some states, while in others we move off to infinity.

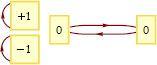

When the state-space is separated into several cycles, the system remains in whatever cycle it started in. Each cycle has its own dynamical rule, but they are all part of the same state-space because they describe the same dynamical system. Let’s consider a system with three cycles. Each of states 1 and 2 belongs to its own cycle, while 3 and 4 belong to the third (see Figure 14).

Figure 14: Separating the state-space into cycles.

Whenever a dynamical law divides the state-space into such separate cycles, there is a memory of which cycle they started in. Such a memory is called a conservation law; it tells us that something is kept intact for all time. To make the conservation law quantitative, we give each cycle a numerical value called Q. In the example in Figure 15 the three cycles are labeled Q = +1, Q = −1, and Q = 0. Whatever the value of Q, it remains the same for all time because the dynamical law does not allow jumping from one cycle to another. Simply stated, Q is conserved.

Figure 15: Labeling the cycles with specific values of a conserved quantity.

In later chapters we will take up the problem of continuous motion in which both time and the state-space are continuous. All of the things that we discussed for simple discrete systems have their analogs for the more realistic systems but it will take several chapters before we see how they all play out.

Laplace may have been overly optimistic about how predictable the world is, even in classical physics. He certainly would have agreed that predicting the future would require a perfect knowledge of the dynamical laws governing the world, as well as tremendous computing power—what he called an “intellect vast enough to submit these data to analysis.” But there is another element that he may have underestimated: the ability to know the initial conditions with almost perfect precision. Imagine a die with a million faces, each of which is labeled with a symbol similar in appearance to the usual single-digit integers, but with enough slight differences so that there are a million distinguishable labels. If one knew the dynamical law, and if one were able to recognize the initial label, one could predict the future history of the die. However, if Laplace’s vast intellect suffered from a slight vision impairment, so that he was unable to distinguish among similar labels, his predicting ability would be limited.

In the real world, it’s even worse; the space of states is not only huge in its number of points—it is continuously infinite. In other words, it is labeled by a collection of real numbers such as the coordinates of the particles. Real numbers are so dense that every one of them is arbitrarily close in value to an infinite number of neighbors. The ability to distinguish the neighboring values of these numbers is the “resolving power” of any experiment, and for any real observer it is limited. In principle we cannot know the initial conditions with infinite precision. In most cases the tiniest differences in the initial conditions—the starting state—leads to large eventual differences in outcomes. This phenomenon is called chaos. If a system is chaotic (most are), then it implies that however good the resolving power may be, the time over which the system is predictable is limited. Perfect predictability is not achievable, simply because we are limited in our resolving power.