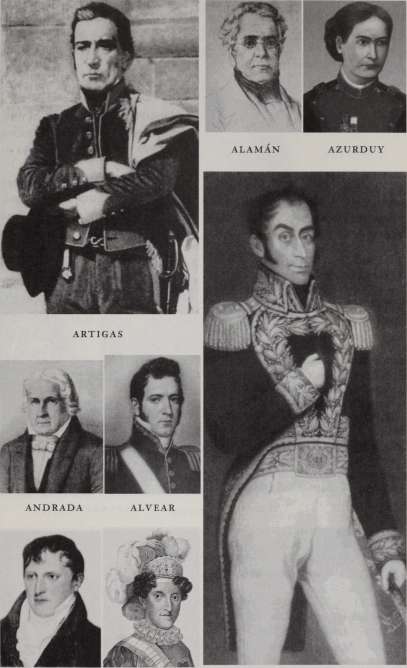

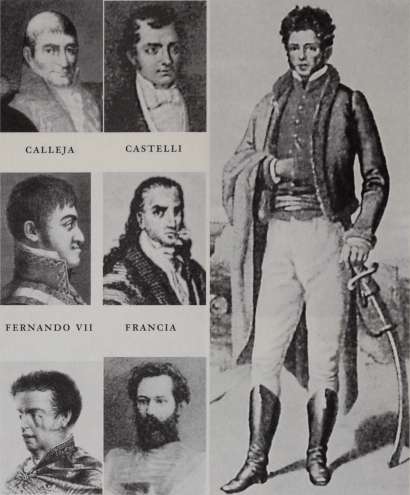

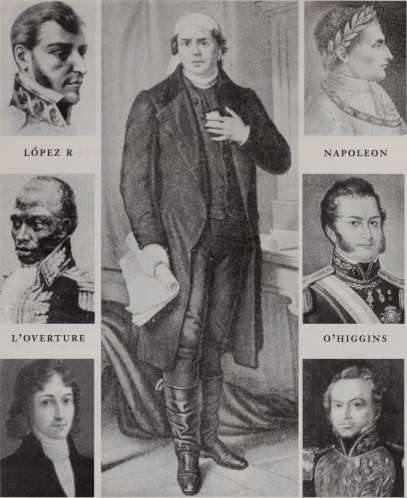

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER

Lucas Alaman, b. 1792—Mexican statesman and historian, Guerrero's

nemesis Ignacio Allende, b. 1769—Hidalgo's second in command Carlos de Alvear, b. 1789—an aristocrat of Buenos Aires Jose Bonifacio de Andrada, b. 1763—a Brazilian founding father;

brothers are Antonio Carlos and Martim Francisco Jose Artigas, b. 1764—federalist leader who challenged Buenos Aires Juana Azurduy, b. 1781—leader of patriot guerrillas in Upper Peru Manuel Belgrano, b. 1770—Buenos Aires revolutionary, defeated in

Upper Peru Andres Bello, b. 1781—Caracas-born man of letters, long resident in

London William Beresford, b. 1768—British officer who fought in Buenos

Aires and Portugal Sim6n Bolivar, b. 1783—the liberator of five countries Tomas Boves, b. 1782—Spanish leader of llanero lancers, defeated

Bolivar Felix Maria Calleja, b. 1753—nemesis of Hidalgo and Morelos,

eventually viceroy Carlos IV, b. 1748—king of Spain, abdicated in favor of son, Fernando VII Carlota Joaquina, b. 1775—Fernando's sister, married to Joao M of

Portugal

Javiera Carrera, b. 1771—woman of a leading Chilean patriot family Jose Miguel Carrera, b. 1785—Javiera's brother, rival of Bernardo

O'Higgins Juan Jose Castelli, b. 1764—Buenos Aires revolutionary, defeated in

Upper Peru Thomas Alexander Cochrane, b. 1775—admiral of the Chilean and

Brazilian navies Fernando VII, b. 1784—king of Spain, the "Desired One" during his

captivity Gaspar Rodr!guez de Francia, b. 1766—dictator who made Paraguay

independent Manuel Godoy, b. 1767—despised lover of the Spanish queen Vicente Guerrero, b. 1783—third major leader of rebellion in New

Spain Miguel Hidalgo, b. 1753—radical priest who began rebellion in New

Spain Alexander von Humboldt, b. 1769—Prussian scientist, explorer, and

expert Agustin de Iturbide, b. 1783—americano officer acclaimed Agustm I

of Mexico Joao VI, b. 1769—prince regent, later king, of Portugal; fled to Rio de

Janeiro Antonio de Larrazabal, b. 1769—Guatemalan leader in the Cortes

of Cadiz Ignacio Lopez Rayon, b. 1773—organizer of the Zitacuaro junta Santiago Marino, b. 1788—Venezuela's "Liberator of the East" Juan Martinez de Rozas, b. 1759—Chilean patriot leader, patron of

Bernardo O'Higgins Servando Teresa de Mier, b. 1765—dissident intellectual priest of

New Spain Francisco de Miranda, b. 1750—precursor of the cause of America Bernardo Monteagudo, b. 1785—Chuquisaca intellectual, collaborator of San Martin Juan Domingo Monteverde, b. 1772—Spanish general who defeated

Miranda Carlos Montufar, b. 1780—companion of Humboldt, son of Juan P10 Juan Pio Montufar, b. 1759—head of 1809 Quito junta Jose Maria Morelos, b. 1765—second major leader of rebellion in

New Spain Mariano Moreno, b. 1778—secretary of first Buenos Aires junta

Pablo Morillo, b. 1778—Spanish general who led reconquest of New

Granada Antonio Narino, b. 1765—conspirator, then patriot leader of New

Granada Bernardo O'Higgins, b. 1778—liberator of Chile, collaborator of San

Martin Manuel Ascencio Padilla, b. 1775—patriot leader of Upper Peru Jose Antonio Paez, b. 1790—Bolivar's llanero ally and later his rival Pedro I, b. 1798—son of Joao VI and Carlota Joaquina, declared Brazilian independence Manuel Carlos Piar, b. 1774—pardo general executed by Bolivar Home Popham, b. 1762—British admiral who attacked Buenos Aires

in 1806 Mateo Pumacahua, b. 1740—Indian leader of 1814 Cuzco rebellion Andres Quintana Roo, b. 1787—patriot intellectual of New Spain Bernardino Rivadavia, b. 1780—liberal president of independent

Buenos Aires Simon Rodriguez (aka Samuel Robinson), b. 1771—revolutionary

educator Manuela Saenz, b. 1793—patriot of Quito, collaborator of Bolivar Mariquita Sanchez, b. 1786—Buenos Aires revolutionary (later

Madame Mendeville) Francisco de Paula Santander, b. 1792—Bolivar's rival in New

Granada Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, b. 1794—young caudillo, helped topple Agustin I Jose de San Mart!n, b. 1778—liberator who bowed out at Guayaquil Antonio Jose de Sucre, b. 1795—Bolivar's right-hand man in the

1820s Leona Vicario, b. 1789—organizer in Mexico City's patriot underground Duke of Wellington, b. 1769—Napoleon's British nemesis in Spain

x Dramatis Personae

VICEROYS

IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

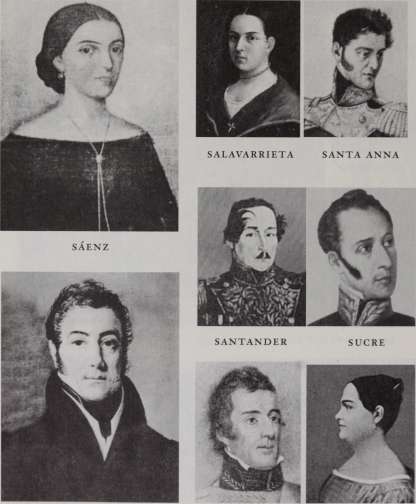

GALLERY

OF THE PRINCIPAL DRAMATIS PERSONAE

BELGRANO CARLOTA

BOLIVAR

JOAO VI GUEMES

GUERRERO

TURBIDE HIDALGO HUMBOLDT LARRAZABAJ

MEJIA

MORELOS

PAEZ

MIRANDA MORENO NARINO PEDRO

PIAR

RODRIGUEZ

SANCHEZ

SAN MARTIN

WELLINGTON VICARIO

CHRONOLOGY

1799 Humboldt begins his travels in America

1806 Renegade invasions at Buenos Aires and Coro

1807 Napoleon's troops enter Iberian Peninsula Portuguese crown flees Lisbon for Brazil

1808 Spanish crown falls into Napoleon's hands

Crisis of the Spanish monarchy begins; juntas form in Spain Cabildo abierto in Mexico City, Iturrigaray deposed

1809 Central Junta coordinates Spanish resistance to Napoleon Napoleon completes conquest of Spain except for Cadiz Who should rule in America? Debate proliferates

Small rebellions in the Andes: Chuquisaca, La Paz, Quito

1810 Cortes and Regency established in Cadiz

Juntas formed in Caracas, Buenos Aires, Bogota, and Santiago First army sent by Buenos Aires to Upper Peru Hidalgo's multitude sweeps through New Spain

1811 Miranda declares an independent republic in Venezuela Civil war begins in Venezuela, New Granada, and Chile Hidalgo captured and executed; Morelos takes over Forces of Buenos Aires defeated in Paraguay, Upper Peru Peru becomes base for Spanish reconquest of Andes British and Portuguese forces retake Portugal from Napoleon

1812 Napoleon's grip on Spain loosens as well

The Cortes of Cadiz promulgates a liberal constitution

The first Venezuelan republic collapses Morelos survives Cuautla, captures Oaxaca

1813 Bolivar declares "War to the Death" Buenos Aires again defeated in Upper Peru Morelos loses momentum besieging Acapulco

1814 Fernando VII restored, annuls 1812 constitution, dissolves cortes

Spanish forces from Peru reconquer Chile Defeated by Boves, Bolivar leaves for exile

1815 Major reconquest force arrives from post-Napoleonic Spain Artigas confederation united against Buenos Aires

Joao VI's United Kingdom makes Brazil equal to Portugal Morelos captured and executed

1816 Spanish reconquest of America complete, except for Rio de la Plata

1817 San Martin crosses the Andes from Mendoza to Chile Bolivar's comeback begins in Venezuela Pernambucan rebellion reveals "liberal contagion" in Brazil

1818 Guerrero renews the spirit of rebellion in New Spain San Martin prepares his assault on Lima

1819 Bolivar wins at Boyaca Bridge, controls New Granada

1820 Constitutionalist revolutions in Spain and Portugal Major Spanish reconquest expedition aborted

San Martin's seaborne invasion of Peru begins

1821 Cortes of Lisbon forces Joao VI's return to Portugal Iturbide and Guerrero join under the Plan de Iguala, enter Mexico City

Central America joins the Plan de Iguala, declares independence

Bolivar wins at Carabobo, while San Martin bogs down in Peru

1822 Prince Pedro declares Brazil independent, crowned emperor Iturbide acclaimed emperor Agustin I of independent Mexico Bolivar and San Martin meet in Guayaquil

1823 Absolutist counterrevolutions seize both Spain and Portugal Agustin I overthrown, Mexico becomes a republic Bolivar's Peruvian campaign begins

1S24 Pedro I consolidates power in the Brazilian Empire Battle of Ayacucho, final Spanish defeat in America

\\ Chronology

Americanos

PROLOGUE: WHY AMERICANOS?

Long live the Sovereign People! Our time has come at last. . .

— "Cancion americana," 1797

Why Americanos, without capitalization? Why America —as will be written here—with an accent mark? Americanos are, after all, simply the people of America. America is the same word in Spanish or Portuguese and English, one could say. And yet it isn't. For Latin Americans, America has never been synonymous with the United States, nor are americanos simply Americans, and the distinction becomes important in the story told here. Therefore, in this book, America will be used to mean what we today call, in English, Latin America, including all the lands colonized by Spain and Portugal. The americanos in these pages are speakers of Spanish or Portuguese, not English.

America and americanos were key terms in Latin America's independence struggles. Until 1807-8, when Napoleonic invasions of Portugal and Spain unleashed a crisis in America, americano was a term generally denoting whites only. But by the time the dust settled in

1825, years of bloodshed had transformed the meaning of americano, stretching the term around people of indigenous and African and mixed descent, the large majority of the population. The transformation had happened as patriot generals, poets, and orators described their struggle as "the cause of America" and called all americanos to join it. The lyrics of the "Cancion americana" of 1797, anthem of a revolutionary conspiracy in Venezuela, exemplify the new meaning at an early date: "Our homeland calls, americanos, / Together we'll destroy the tyrant." 1

The patriot language of America only exceptionally applied the terms of identity— mexicano, venezolano, colombiano, chileno, brasileiro, guatemalteco, pernano, and so on—associated with today's Latin American nations. From modern Mexico to Argentina and Chile, the patriots of Latin America's struggle for independence constructed a binary divide separating all americanos, on one hand, from europeos (Europeans, meaning European-born Spaniards), on the other. This might seem unremarkable at first. After all, what more obvious separation than the one created by the Atlantic Ocean? Had not the United States already established an analogous American identity?

To the contrary, the semantic evolution of the word amerkano marks a pivotal moment in world history, something no less momentous than had occurred in the English colonies of America decades earlier. The most obvious social distinctions in colonial America did not divide americanos from europeos at all. The colonization of America had created starkly hierarchical societies organized by a caste system. Indians, free people of African descent, and various mixed-race castes differed far more from the white americano ruling class than did americanos from europeos. To summarize the process that we are about to trace in detail, the overwhelmingly white patriot leadership embraced the new, broader meaning of americano because that maximized their chance of victory against the mother country. If everyone born in America—everyone in the strongly variegated population that had arisen from the mingling of individuals from three continents— was an americano, and if all were on the same side, the tiny minority of European-born Spaniards (less than 1 percent of the population) did not stand a chance of maintaining colonial rule. To define Americas rainbow of castes as the americano people recognized the truth on the ground, but it also created a new truth, an airy but potent abstraction. That abstraction was the Sovereign People, who deserved nothing less than a government "of, by, and for the People." And, unlike what had occurred with the independence of the United States in the 1780s, the

. imeriamos

Sovereign People of America who emerged in the 1820s included a nonwhite majority.

The more or less simultaneous creation of a dozen independent nations in America was therefore momentous in a manner that U.S. independence was not. Both signaled important future directions in world decolonization. U.S. independence certainly modeled the creation of a new republic in what had been a European colony, and it inspired a number of influential americano patriots. But one event does not constitute a trend, and people of non-European descent were largely excluded from the U.S. republican model. The creation of the United States of America embodied basic claims of self-determination only for people of purely European descent. In contrast, the mass production of aspiring nation-states in America, in the following generation, did constitute a trend and clearly established a template for future decolonization.

The americanos followed the U.S. example, embodying popular sovereignty in a written constitution produced by a nationally elected constituent assembly. But the new template departed from the U.S. example by formally including large populations of indigenous, African, and mixed descent as citizens in that process. (Haiti, it must be recognized, had really pioneered this innovation, but it started no trends, being an example much more feared than imitated by upper-class political leaders in America.) The americano version was imperfect, to say the least. Citizenship for everyone remained more theoretical than real for many decades. Nonetheless, the independence of America meant that the Western Hemisphere belonged to republics. So claimed the U.S. Monroe Doctrine in 1823, and over the course of the nineteenth century americanos made that vision a reality. By the time that European colonies in Africa and Asia gave way after World War II, the successful decolonization of Latin America had become an established, if still connective, fact of global history. Americano success ensured the currency of the constitutional, republican template in the new African and Asian nations that proliferated in the second half of the twentieth century. The general dissemination of the model had its limits, obviously. Still, it constituted a truly global triumph of the ideas that U.S. parlance these days often calls "Western" political values, ideas that the rest of the world tends to call liberalism.

In fact, the word liberal was coined in Spain during the fight against Napoleon, to describe Spanish patriots whose banner was liberty. Liberals were, in their own terms, enemies of servitude. They stood for constitutional government with the guarantee of civil liberties

Prologue: Why Americanos?

and for a free market of both goods and ideas, which no official truth, no one group or interest or opinion, should ever dominate totally. The starting point of their political thinking—provoked, as we shall see, by the shocking eclipse of the Spanish crown—was popular sovereignty.

In order to theorize popular sovereignty, it was necessary to define the Sovereign People, which meant defining the nation. And the new nations of America were defined from the outset to include people of indigenous, African, and mixed descent. This process of national self-definition involved some tactical denial and self-delusion, and yet it was, if anything, an even more significant americano contribution to world history than the dissemination of liberal republicanism. Benedict Anderson's influential book Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism emphasizes the role in that global process of "Creole pioneers"—by which he means the very people whom I call (and who called themselves) americanos. Anderson gives far too little importance to the wars of independence as formative experiences in America, but he has helped a generation of scholars see Latin American independence as a pivotal moment in the global development of nationalism.

Americanos is not the term used, most commonly, by histories of Latin American independence written in English. Instead, they call American-born whites "Creoles"—a translation of the Spanish word criollo (hence Anderson's "Creole pioneers" of world nationalism). Americanos is a better term because it clarifies the crucial extension of the definition of Sovereign People from whites only to anyone born in America.

Historians of Latin America view the significance of 1808-182 5 in widely divergent ways. Patriotic history (historia patria) in each country has provided mythic narratives of exemplary heroes and foundational acts, narratives of the sort that configure national identities around the world. Artigas, Andrada, Belgrano, Bolivar, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Miranda, Morelos, O'Higgins, Paez, Pedro I, San Martin, Sucre, and Santander—a sampling of americano leaders—are the protagonists of historia patria. They are the names of cities, parks, states, and avenues, unquestionably names to know for anyone who wants to understand the independence of America. But in the patriotic imagination, these heroes are also great men or women whose superior intelligence, virtue, and bravery are held up for inspiration and imitation. That is not the approach taken here. For me, these heroes are inspiring not because they were perfect but because they weren't.

. [meriamas

Current historiography on Latin America asks above all what impact independence had on the colonial hierarchies, particularly on the relationship between the ruling white minority and the subjugated majority of African and indigenous descent. Because colonial hierarchies eroded only slowly in independent America, academic historians have tended to stress the disappointing outcomes of independence. Republics, after all, were supposed to be societies in which the Sovereign People consisted of equal citizens. Slavery and peonage were fundamentally incompatible with republicanism, although the incompatibility could be finessed for decades, as in the United States. The main patriot movements had committed themselves rhetorically to ending the caste stratification so prevalent in America. But rhetorical commitments do not always hold, and after independence republican ideals were sorely tested.

These independence struggles produced unified nations where the rule of law prevailed unerringly, where all enjoyed equal citizenship, where republican governments represented general interests, only in theory. In fact, "Western" political values have had a troubled history in Latin America (as in the rest of the world, including Europe) because they conflicted with deeply held values and habits that preceded them. Indeed, Western political values have been both powerfully championed and stubbornly resisted in America. By demanding their right to self-determination, americanos defined the direction of world history two hundred years ago, but their bids for effective citizenship were usually defeated before the twentieth century. That part of the story is best left for the epilogue.

This book is different from straight patriotic and scholarly tellings of Latin American independence. The purpose here is to weave together patriotic names to know with a balanced assessment of events in a unified narrative covering the whole region colonized by Spain and Portugal. Portuguese America (Brazil) plays a less important part than does Spanish America, which was a more populous place and one in which the process of independence was more complex, producing a score of modern countries. Yet the same general forces were at work everywhere in America. Let us begin with the following ironic and infrequently made point. Overall, americanos were loyal to their king and not especially eager to embrace revolutionary ideas emanating from the United States and France when, in 1799, one of the most remarkable travelers in history landed on their shores. That traveler, a Prussian named Alexander von Humboldt, an outsider of insatiable curiosity, can be our tour guide in late colonial America.

Prologue: Why Americanos?

DISCOVERING AMERICA

i799-1805

In 1799, travel accounts were the basic source of information about America for readers in Europe and the fledgling United States. In that year, Alexander von Humboldt, surely the most influential traveler ever to visit America, began his famous journey through territories that remained little known to the outside world. Humboldt never used the name Latin America, because it did not yet exist and would not, in fact, during the entire period covered by this book. Within a very few years after Humboldt's visit, America would give birth to a dozen new nations in a painful labor. But none of that was evident in 1799.

Humboldt and Bonpland Discover America

Alexander von Humboldt—would-be explorer, all-purpose scientist, guy who liked guys—was twenty-nine years old when he first set foot in the New World in July 1799. You have to love the young Humboldt: the odd boy who liked bugs too much to be a bureaucrat, as his mother wished; the twenty-year-old who went to Paris for the delirious first anniversary of the French Revolution and worked for a few days as a volunteer helping construct the city's Temple of Liberty for the celebration. Imagine him as the dedicated graduate student of geology and botany who wanted above all to explore the world outside of Europe.

Consider him the cocky Berliner whose excellent Spanish convinced the king of Spain to let him into America when few outsiders were allowed to visit there.

Or you may prefer not to like Humboldt, who, after all, reeked of privilege. He was the sort of kid whose family had a castle, the sort who could afford to bankroll his own five-year scientific expedition. This lanky young German whose democratic principles failed to banish his air of superiority was too good-looking by half. And Humboldt was quite definitely a know-it-all. He represents both the bright and dark sides of the European intellectual and scientific quickening called the Enlightenment. The pure, raw joy of comprehending the universe

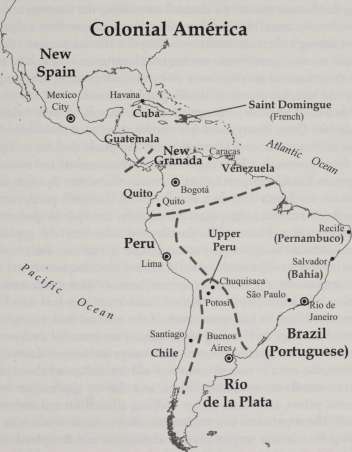

Colonial America

Saint Domingue

(French)

►Chuquisaca

| • ^ Sao Paulo

. Potosi\

Santiago? » Buenos^ */ Brazil

io de Janeiro

(Portuguese)

Rio de la Plata

Discovering America J

pulsed palpably in the young Humboldt. Darwin said Humboldt's Personal Narrative (the journal of the trip that took him to Venezuela and Cuba, the Andes, and Mexico) was his great inspiration. But Humboldt also exemplified the Enlightenment's will to mastery. To "discover" the world was to access it. Classification, one of the Enlightenment's intellectual passions and one of Humboldt's, was a technology of control. Not by accident was Humboldt one of the most famous men in Europe during the great age of European global colonization.

Humboldt received permission from Carlos IV to travel collecting specimens of plants, animals, and minerals, measuring winds and currents, altitudes and latitudes. He would pursue all elements of natural history, a name for the integrated study of the changing earth, most especially the interactive relationship between living things and their environment. Because a French scientist who visited South America in 1735 had heard rumors of a channel connecting the Amazon and Orinoco river systems, Humboldt would canoe for more than a thousand miles through the rain forest searching for the connection. And he would repeatedly satisfy his penchant to climb up any volcano he found and then descend into its crater to investigate choking ash, gurgling lava, and invisible plumes of deadly gases firsthand.

Humboldt and his colleague Aime de Bonpland were originally headed for Cuba. But typhoid fever broke out aboard their ship off the coast of Venezuela, and Humboldt and Bonpland decided to land at the first opportunity. That opportunity was an ancient and somewhat forgotten Caribbean port called Cumana, the oldest Spanish settlement on the South American continent—at that time partly in ruins because of a recent earthquake. Fortunately, the Spanish governor of Cumana was a Francophile intellectual who actively applauded Humboldt and Bonpland and seemed eager to facilitate their explorations in all ways. The earth around Cumana was alive as only the tropical earth can be, "powerful, exuberant, serene," Humboldt wrote his brother in a deliriously happy letter. 1 Life aboard ship had suited him, he reported, and he had spent much of the time on deck taking astronomical readings and hauling up samples of seawater for analysis. Not mentioning any typhoid fever on his voyage for fear of alarming his brother, the ecstatic twenty-nine-year-old instead raved about tigers, parrots, monkeys, armadillos, birds, and fish in spectacular colors, coconut palms, and "semi-savage Indians, a beautiful and interesting race." 2 The weather in this tropical paradise seemed to suit him, too. Setting foot in the tropics excited Humboldt and Bonpland to the point that they could not carry on a coherent conversation for several

0 Americanos

days, so rapidly did each marvel supersede the last. Venezuela was rife with species unknown to Western science. And for a few coins, one could rent a house with servants for a whole month. Nearby Caracas, Humboldt assured his brother, had one of the healthiest climates in America. So he was changing his plan. He and Bonpland would spend some months in Venezuela before proceeding to Cuba. The rumored approach of British warships made that plan doubly prudent, because Spain and Britain were at war.

Meanwhile, a daily slave market outside the window of his new house spoiled Humboldt's visions of paradise. Humboldt and Bonpland found the view heart-rending and "odious." Humboldt despised slavery, and he wrote in fury to his brother about seeing buyers force people's "mouths open as we do with horses in the market." 3 The two men would see many, many slaves on the shores of the Caribbean. Only one spot was free of slavery: France's former sugar colony Saint-Domingue, modern Haiti, where the spirit of the French Revolution had helped a slave rebellion become a revolution that destroyed slavery utterly and wiped out the white master class along with it. Cuba, Humboldt's next planned destination, was Spain's great experiment in slave-driven plantation agriculture. And slavery was only one of many social injustices that European colonization had brought in its train.

Yet Humboldt later wrote that during the 1799-1805 trip that made his reputation, he did not anticipate the tempestuous movements for independence that began shortly after his return to Europe. Why not? The British colonies of North America had recently won their independence from Britain. Haiti had won independence from France. Neither Spanish America nor Brazil was strongly garrisoned by European forces. Add to that the resentments of colonial merchants limited by the Spanish monopoly trading system. Factor in the frustration of American-born Spaniards because of the colonial government's constant favoritism toward the European-born. Apply the anger and humiliation of the downtrodden black and brown people who constituted three-quarters of the population, occupying all the lower rungs on the colonial caste system in Spain's America. With all that, a pervasive desire for decolonization might seem a foregone conclusion. Humboldt saw no great love for Spain, and he found a few people who seemed surprisingly proud of being called americanos. But how ripe for revolution was America, really?

In 1800, America as a whole showed few revolutionary inclinations. Humboldt traversed America's major population centers (including three of its four viceregal capitals, Lima, Bogota, and Mexico City), its

Amazonian lowlands, the Caribbean basin, the Andean highlands, and much of Spain's most important colony, New Spain. Here is the situation he encountered. European-born Spaniards, called espanoles europeos (europeos for short), were less than i percent of the population of America. On the other hand, American-born Spaniards, espanoles amer-icanos (americanos for short) accounted for roughly a quarter of the population. Europeos acted far superior to their americano cousins. In addition, the royal government and the church preferred europeos over americanos for employment and office holding—an old and angry grievance of the americanos. Moreover, the richest and best-connected merchants—virtually all those who carried on transatlantic commerce—were invariably europeos. Jealous americanos regarded prosperous europeos as heartless money-grubbers and condescending, would-be aristocrats. Resentment of europeos found voice in unflattering epithets, most notably the names chapetdn and gachnpin. Both europeos and americanos felt superior to, and lived by subjugating, the roughly three-quarters of the population whose descent was at least partly African or indigenous American. However much arrogant europeos got on their nerves, americanos anxiously affirmed their shared Spanishness in contrast to the Africans, Indians, and mixed-bloods who occupied the lower rungs of the caste hierarchy. The majority of the population lived in the great frontiers and hinterlands of America, along tropical rivers, in rain forest clearings, on Andean slopes, outside any effective government control, preoccupied with farming or fishing and supplying their own needs in whatever way possible. America's sprawling frontiers could easily provide subsistence for many times the region's population. Only in rare cases was hunger a motive for rebellion.

The 1780s had seen tax rebellions in several parts of America, but only one of them, the Tupac Amaru rebellion of Peru and Upper Peru (today Bolivia), was really threatening. These rebellions generally expressed localized grievances and demanded limited reforms. Their rallying cry was usually something like "Long live the king and death to bad government!" Often they were responses to royal policies that limited economic activities in the colonies. These policies had not gone away. True, some exceptions had been made to the official Spanish trade monopoly, whereby Spanish merchants normally had exclusive rights to buy and sell in the seaports of America, but it had not been abolished. One way or another, however, the moment of colonial rebelliousness had passed by 1800, when Humboldt observed mat most people, including (white) americanos, Indians, mixed-bloods, and

10 Americanos

blacks, expressed overwhelmingly loyalty to the Spanish crown. To a young man imbued with the spirit of revolutionary transformation, the people of America seemed, overall, rather apathetic.

More than internal discontent an external clash between European empires was causing colonial disruption in 1800. Spain and Britain had been often at war in the eighteenth century. Colonial militias had been formed to defend America against British intrusions on land, but the British navy ruled the waves. Colonial goods piled up on the docks and passengers found no passage, as all communications were paralyzed by British warships operating from island bases in the Caribbean. Trinidad, a formerly Spanish island, had become the most recent of these. When Humboldt and Bonpland finally emerged from the rain forest to take ship for Cuba, they found that Spanish ships dared not sail along the Venezuelan coast. Humboldt and Bonpland had to wait four months in Venezuela for a smuggling skiff that served the pent-up Venezuelan demand for British goods by shuttling between Trinidad and the mainland. And no sooner had they put to sea than marauding Nova Scotia privateers (pirates working as military contractors, so to speak, for Britain) swooped down on them. Humboldt and Bonpland found themselves deposited aboard a British naval sloop. Fortunately, the British captain, who had read about their scientific expedition, politely delivered them back to Venezuela, where they continued to wait in vain for a Spanish ship to take them to Cuba. Finally, they had to take passage on a neutral U.S. cargo vessel carrying tons of foul-smelling beef jerky.

Consider a Continent of Frontiers

Beef jerky is made by piling salt-slathered meat in the sun. The salt and heat suck the moisture out of the rapidly decomposing flesh, halting the process before it is too far advanced. Jerky was a product of cattle frontiers all over America. In the era before refrigeration, jerking beef was the only way of more or less preserving it for shipment overseas. High in protein, rich in flavor, jerked beef was principally a ration for sailors and, above all, slaves—the reason that Humboldt's boat full of jerky was bound for Cuba. The shipment that made Humboldt and Bonpland hold their noses may have originated on the Orinoco cattle frontier of Venezuela or much farther south.

Aside from a fringe of coastal settlements, most of South America remained a frontier in 1800. In fact, the population of the whole

continent at the time would probably fit into a metropolis such as Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires, or Mexico City today. Humboldt and Bonpland had a special interest in America's vast frontiers, where they hoped to discover species new to European science. In November 1800, though, the two intrepid explorers were headed to relatively tame and well-known Cuba, so we will visit another frontier without them. Across the continent, on the grassy plains of America's south Atlantic coast, a Spanish officer named Felix de Azara was thinking about the Rio de la Plata frontier, land of the fabled cowboys called gauchos.

The Rio de la Plata frontier was an endless, mostly treeless plain where hundreds of thousands of half-wild horses and cattle roamed free. This frontier was home to highly mobile indigenous people, comparable to the Apache or Sioux, who had learned to ride and hunted the feral cattle instead of bison. To colonizers such as Azara, this frontier was a resource to be secured for Spain. Though much older than Humboldt and no democrat, Azara resembled the Prussian in his habit of constantly observing, analyzing, and taking notes. He was about to write a famous report to the Spanish crown. Azara, his report, and his assistant, Jose Artigas, illustrate something about the coming wars of independence. On the eve of those wars, revolt was the last thing on people's minds in America as a whole. When events in Europe involved americanos in international conflict against the French, against the British, they reacted as loyal subjects of their king.

Felix de Azara had first come to America as part of the Spanish team sent to survey and mark a border between Spanish and Portuguese claims. The Rio de la Plata frontier was the one part of America where Spanish and Portuguese claims clashed substantially, though, and when negotiations collapsed, Azara stayed to advance the royal project in a different way—by populating the frontier with loyal, armed Spanish subjects. To secure the frontier against the Portuguese, Azara advised the Spanish government to found a string of towns and distribute land for free in ranch-size portions to men who agreed to occupy the ranch with their families, maintain a shotgun, and serve in the militia. The Portuguese had used that model very successfully. Azara recommended that Portuguese settlers willing to live under Spanish rule should be encouraged to set a good example for the Spanish settlers.

The Spanish-speaking population of the Rio de la Plata frontier did not impress Azara. Possibly half passed as espanoles americanos, he reckoned, but many actually had some Indian ancestry The others included pardos (people of mixed European and African descent), Guar-anf Indians from the nearby Jesuit missions, and a few African slaves.

12 . Imericanos

The americanos did not hesitate to work alongside pardos, Guarani, or even slaves, so long as that work was done on horseback. Few in the Plata countryside owned land, but everyone had horses. Azara made fun of the frontiersmen's dress, including a Guarani loincloth called a chiripd, worn by whites, pardos, and slaves because it was ideal for riding horseback. Grown to manhood on the violent frontier, lamented Azara, these gauchos killed each other "as calmly as one cuts the throat of a cow." 4

Azara wrote in great disgust that the herds of the Plata frontier had been decimated during the 1700s by the thoughtlessness of Spanish cattle hunters who launched their expeditions in the spring, when many calves died needlessly in the confusion. The Charrua Indians— who, unlike the Guarani, had not accepted Christianity-competed for cattle, of course. Cattle were their subsistence. But the Spanish cattle hunters took cattle by the tens and hundreds of thousands, not for subsistence but for their hides, the only part of them that could be profitably exported to Europe. The carcasses of these animals, roughly eight hundred thousand a year in the previous twenty years, were almost all left to rot on the plains. Azara estimated that properly managed herds would grow to almost ninety million cattle in three decades and produce enough beef jerky for all the slaves in Cuba.

Azara was fortunate to have as his assistant a local military officer who knew the Rio de la Plata frontier and its people intimately, maybe even a little too intimately for Azara's taste. Captain Jose Artigas was the sort who went by a nickname, Pepe, and in the presence of gaucho frontiersmen acted very much like them. The europeo Azara was not particularly good at dealing with gauchos, but the americano Artigas had no equal at it, making him helpful indeed. Artigas came from a family well established on the frontier. Both his father and his grandfather had captained the mounted militia of the frontier charged with protecting ranchers and cattle hunters from heathen Indians such as the Charrua. Artigas had left home to try his luck on the plains at the age of fourteen. He became one of those americanos who joined cattle-hunting expeditions and mingled with gauchos, to Azara's distress. He stayed out on the grasslands for many months at a time, roaming throughout the upper Rio de la Plata plains. His home base during this period was an old mission settlement called Soriano, full of Indians and mixed-blood mestizos such as plucky Isabel Velasquez, who bore Artigas four children. Pepe and Isabel had not been able to marry, presuming that his family would have allowed it, because she already had a husband in prison.

Young Artigas had been accused of driving contraband herds of two thousand cattle between the Spanish and Portuguese settlements. He was on good terms with both the Portuguese and the Charrua Indians and had an enthusiastic following among the multihued Spanish-speaking gaucho riffraff of the countryside. In 1795, the governor of Montevideo, Spain's fortified port city on the edge of the Rio de la Plata frontier, issued a warrant for the arrest of the accused contraband herdsman. However, the Buenos Aires viceroy, who was the foremost Spanish authority in the Rio de la Plata, soon offered Artigas an amnesty and recruited him to head a new mounted police force. Overnight, to the delight of his family, the budding renegade underwent an extreme transformation and became a militia captain like his father and grandfather. Artigas was expected to focus on contraband and on the Charrua, two subjects that he had evidently mastered. But Artigas proved notably ineffective at killing Charruas. Other commanders excelled at surprising Charrua encampments and slaughtering men, women, and children, while Artigas seemed unable or unwilling to attack his former companions.

One day Jose Artigas would make war on Spain and become the father of his country, the republic of Uruguay. But in 1801 he was a loyal—if "Indian-loving" and, until lately, not particularly well-behaved—military officer of Carlos IV, the king of Spain.

Humboldt's Adventure Continues

Humboldt spent only two months in Cuba. Its position astride major sea routes had made Cuba well known, and it was not a land of uncharted terrain and undiscovered creatures to be classified by genus and species, as were parts of the Amazon basin. A perpetual target for English raids, Cuba had become, in Humboldt's day, the great economic success story of America. So Humboldt did no exploring and instead made the collection of statistics on demography, agriculture, trade, and government finance his main activity during his two-month stay in Cuba. The primary object of his attention was chattel slavery.

After returning to Europe, he would use the materials he collected to argue that slavery was uneconomical as well as obviously immoral. People in the future, he predicted correctly, would have trouble believing that the routine inhumanity of slavery as then practiced in Havana (or Washington, D.C., or Rio de Janeiro) was once accepted as normal. "Slavery is without doubt the greatest of all evils to have plagued

14 Americanos

mankind," he wrote in what proved to be one of the most quoted passages of his voluminous travel account. 5 Humboldt's argument was superbly informed. He recorded how the indigenous people of Cuba had been entirely destroyed by the late 1500s, how the island remained a sparsely populated hide-producing frontier zone in the 1600s. Not until the British occupied Havana in 1762, opening the door for British slave traders, did the Cuban economy begin to take off. The spreading cane fields of the 1780s and 1790s made western Cuba an agricultural dynamo. By the time Humboldt and Bonpland arrived, thousands of chained Africans passed through the Havana customs house yearly, with a steady upward trend, and the number for the whole island, including contraband slaves, was much higher. Cuban slave owners imported tons of jerked beef, and many Havana streets stank of it. Slave imports and sugar exports generated millions of dollars annually in tax revenues, and free-spending Havana sugar planters were becoming conspicuous in French, Spanish, and Italian cities.

Fortunately for Spain, Cuba's slave-driven economy made Cuban plantation owners extremely conservative and, in the light of events in nearby Haiti, particularly reluctant to condone rebellious behavior. For that reason—and also because Cuba was fantastically profitable, powerfully garrisoned, and absolutely central to Spanish military strategy in America—Spain's "Ever Faithful Isle," as Cuba came to be called, did not participate in the revolutionary events about to unfold on the mainland.

Their curiosity satisfied, Humboldt and Bonpland returned to the South American mainland at Cartagena and, during June and July 1801, ascended the powerful Magadalena River in what is today Colombia. Their goal was to explore a different face of America, the Andean highlands. Like the highlands of New Spain (modern Mexico) and Guatemala, the lofty plateaus of the Andes mountains had supported relatively dense populations of village-dwelling indigenous farmers for thousands of years before the European invasion. These were not frontiers, but rather the opposite: the core areas of Spanish colonization in America.

Before steam navigation, ascending the Magdalena River was a grueling process. Teams of boatmen, almost always men of African descent, pushed the craft upstream against the strong current using long poles, keeping to the shallows along the bank where the current ran less swiftly (but the tropical sun beat down just as hard). To reach Bogota from the coast took six weeks on the river and then another three weeks climbing up something that more resembled a mountain

streambed than a road. There were no alternative routes. Humboldt took the opportunity to study the several species of alligators, trying to determine their relationship to Nile crocodiles. When the two scientists finally arrived in Santa Fe de Bogota, capital of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, the scientific and intellectual community gave them a grand welcome. But Bonpland's health had been undermined by the tribulations of the journey. For a European, the chilly mists of Bogota at eight thousand feet seemed more congenial and inviting than the steaming lowlands of the Caribbean coast. So the two men settled in for a four-month respite, much of which they spent in the library of Jose Celestino Mutis, one of the first Spanish scientists to apply the Linnaean botanical classification system.

In Bogota, Humboldt found a city locked inside layers of soaring, steep-sloped mountains where, then as now, roads were hard to construct. New Granada appears to have been, by Humboldt's comparison with Cuba, something of a colonial disappointment. Though populous and enormous, it generated little wealth for Spain. The presence of highland farming Indians (and hoards of gold objects) had drawn the Spanish conquerors to the high plateau of Cundinamarca, the location of Bogota, but for now, those farms could grow nothing that could be exported profitably to Europe. The jagged geography of the northern Andes made only the most valuable substances, such as gold, worth transporting to the coast. Anything less precious than gold would not pay for itself. This fact made most of New Granada's rural population a subsistence peasantry, sprinkled through jumbled ridges and valleys, clustering around small, widely separated cities, interspersed with small indigenous groups and steep stretches of trackless wilderness. There were some sugar and slaves around Cartagena on the Caribbean coast and along the Cauca River, but nothing to compare with Cuba.

Therefore, the Viceroyalty of New Granada mattered less to the Spanish crown than did its other three American viceroyalties. The Viceroyalty of Peru and the Viceroyalty of New Spain, with their great silver mines, were richer and better established. The Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata got more royal attention because of the ongoing competition with the Portuguese in the vicinity. But the high Cundinamarca plateau around Bogota was remarkably lush and beautiful, and the fabulous botanical collection assembled by Mutis made the visit worthwhile in itself. Furthermore, New Granada abounded in something Humboldt especially adored, volcanoes. As soon as Bonpland felt ready to hike, the two were on the road again, traveling south through the Andes toward Lima, climbing every volcano on the way Ahead, looming

16 Americanos

over the city of Quito, which Humboldt found lovely but overly solemn with its cold and cloudy skies, stood the great snow-capped volcano called Pichincha. Humboldt climbed Pichincha in the company of an Indian guide. At one point, he and the guide found themselves walking on an ice bridge over part of the yawning crater, its circumference many miles around. Humboldt had such a good time that he convinced Bonpland and Carlos Montufar, a new friend, son of a local noble, to climb Pichincha with him again two days later. All three then tried their luck on Chimborazo, a volcano that towered over all the others. Humboldt climbed six snow-capped volcanoes around Quito, impressing some highlanders and mystifying others. Scaling Chimborazo, then believed to be the highest mountain in the world, earned him the nineteenth-century equivalent of international stardom. Carlos Montufar was so exhilarated by the experience that he got his father's blessing to accompany Humboldt and Bonpland for the rest of their journey.

Enter Simon Bolivar

July 1802, the moment of Humboldt's climb to international celebrity on Chimborazo, was also a moment of elation for nineteen-year-old Simon Bolivar, just returning to Venezuela after a three-year stay in Madrid, the capital of the Spanish Empire. Living there with his uncles, the well-heeled young man had acquired a bit of courtly polish, including his first serious attention to spelling as well as private lessons in French and dancing. Young Bolivar strutted around Madrid in a militia uniform (without doing any actual military service), spent a great deal of money, and, in less than a year, fell madly in love with a young women named Maria Teresa Rodriguez de Toro. Bolivar was then seventeen. The fact that Maria Teresa was twenty months older than her beau was a bit odd but no impediment to their marriage. Theirs was a brilliant match, the Bolivar and Rodriguez de Toro families both being rnantuano families (part of the Venezuelan elite) and longtime allies in Caracas politics. Still, they had to wait a year and a half while the families negotiated careful prenuptial agreements because of the amount of property involved. Immediately after the wedding in Madrid, Simon and Maria Teresa sailed for Venezuela.

All was right in their world. They were young, rich, and privileged, belonging to the thin upper crust of colonial society—and they really were in love, something of a rarity for people so rich, among whom a

marriage alliance was customarily family strategy. Immediately upon arrival at the port of La Guaira, they sent couriers racing up the slopes to Caracas to inform Simon's uncle and Maria Teresa's aunt. Also in the port of La Guaira, Maria Teresa met a passenger about to embark for Spain, so she took the opportunity to write her father announcing their safe arrival. "My adored Papa," begins the letter, which is chatty and unremarkable, filled with details of the voyage, news of her cousins who came to meet them in La Guaira, lots of regards, and earnest wishes for her father's good health. 6 The letter would not be worth mentioning were it not, apparently, the last one she ever wrote.

After effusive greetings to friends and relations in Caracas, the happy couple traveled immediately to one of the family's several properties, a sugar plantation just inland from Caracas. They envisioned a life for themselves in the exuberant Venezuelan countryside that Simon had visited often as a boy. Maria Teresa, born in Madrid, was seeing it all for the first time: the huge trees full of parrots and bromeliads, the cacao orchards on the hillsides, the green carpets of sugarcane in the valleys. There is no record of how she reacted to becoming the mistress of a plantation worked by Africans in bondage. Her family's fortune was, of course, built on slave labor, as were the fortunes of Venezuela's dominant families generally. Maria Teresa Rodriguez de Toro had always known that. But now she had to see it.

No doubt she simply got used to seeing slaves and began to consider it normal. That was the most common attitude in slave-owning lands. Slavery that is purely a chamber of horrors cannot last, so slave owners mixed discipline with paternalism. In some cases, warm relationships formed between them and their slaves, especially between masters and domestic servants. Simon Bolivar, like so many children of cacao and sugar planters, had been raised by a slave nanny, his black wet nurse Hipolita. Years later, when he was a victorious general leading his army in Caracas, Bolivar spotted Hipolita in the crowd and dismounted to embrace her. He also grew up with slave playmates, the perfect arrangement for a little boy who had to win whenever he competed. Paternalism (and occasionally self-interest) led to the practice of freeing favored slaves or allowing them to buy their freedom, a process called manumission. Humboldt remarked on the frequency of manumission in America.

Over the years, the descendants of manumitted slaves came to constitute a significant portion of the Venezuelan population. These free blacks were normally mixed-descent pardos. Like many of America s mixed-descent populations, the pardos were upwardly mobile. They

io Americanos

had no interest in laboring on plantations and refused to do it for any price that the planters were willing to pay. Many were artisans who earned as much as poor whites. But the caste system, designed to keep people in their place, stipulated that pardos, no matter how prosperous, could not do certain things associated with high social rank—such as ride a horse, wear silk, carry a sword, or study at a seminary—reserving those honors for bona fide (white) americanos. These limitations chafed upwardly mobile pardos, and here some resourceful servant of the Spanish monarchy identified a revenue source. In the mid-1790s, royal officials announced the sale of a new item: exemptions that would make pardos legally white, granting them permission to do whatever americanos could do.

The city council of Caracas, called the cabildo, where great families exercised quasi-hereditary control, howled with fury. What was the king thinking? The cabildo mobilized the mantuano class to protest this infamy. Simon's uncle and guardian, Carlos Palacios, in whose house the boy lived at the time of the protest, was a ringleader of the protest. The city fathers explained their case with painful clarity in a letter to the king. The pardos were descended from slaves. Some still had slaves in their families. Slaves, of course, were beaten and terrorized as a necessary part of keeping them enslaved. (This they knew well, obviously, being slave owners themselves.) Their point was that slaves had been degraded, stripped of "honor." So how could prosperous pardos be treated as the equals of people such as themselves— people defined by their honorable family histories, by their blood, clean from the stain of non-European mixture? The Marques de Toro, Maria Teresa's uncle, also signed this letter of protest to the king. The last thing the titled nobility needed was a challenge to the caste system.

The pardos had recently become insolent, explained the city fathers, crowding into the towns (or out onto the frontiers) instead of laboring on plantations alongside the slaves. The Caracas cabildo mentioned labor needs insistently in the protest. In town, the pardos became blacksmiths, carpenters, silversmiths, tailors, masons, shoemakers, and butchers. Thanks to their easy access to basic subsistence, pardo artisans could charge prices that the city fathers considered outrageous. But worst of all was the participation of thousands of pardos in the new colonial militias. The Caracas cabildo thought that putting pardos in uniform made them uppity. Pardos with a red militia badge in their hats were much too ready to speak up for themselves when appearing before a magistrate.

There was no trace of irony in the cabildo's lament. In the colonial Venezuela where Simon Bolivar grew up surrounded by enslaved servants, the principle of inequality, or rather hierarchy, ruled. Fairness was not an issue. Rulers spoke of inherited honor and privilege without embarrassment. People without honor simply did not deserve the same treatment as honorable people. Only troublemakers tried to work their way up in life. A person stripped of honor should shut up and hang his head in court, believed the cabildo. Moreover, honor, the index of inequality, ran in families. A manumitted slave who did well as a tradesman should know his place, and so should all his children. Finally, puffing themselves up to full "sons of the conquistadors" size, the city fathers warned His Majesty that swarms of "legally white" par-dos entering the church, commerce, and public office would drive all honorable people away in understandable disgust. The grim day would arrive, they warned, when Spain would be served only by blacks. Who then would defend the realm and control the slaves?

This last point they considered the critical one. Controlling the slaves had become a major concern in the 1790s because of the ongoing Haitian Revolution. When a massive revolt of plantation slaves had demolished planter control in the French colony formerly called Saint-Domingue, recalled the cabildo, the agitation of free pardos had detonated the explosive charge. Free pardos had hoped that the principles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, proclaimed by the revolutionary National Assembly in Paris, might allow them to become equal citizens of the French Republic. The master class of Saint-Domingue had tried to stifle such aspirations in the National Assembly. Robespierre's radicals insisted on declaring the principle of racial equality, but it did not apply to slaves. Unlike the free pardos, the slaves of Saint-Domingue could not stake their hopes on the French National Assembly. Stimulated by talk of the rights of man and denied any hope of enjoying those rights, the slaves rebelled. Their chief leader, Toussaint Loverture, rose to prominence during a decade of bloody fighting and eventually distributed a constitution that abolished slavery and outlawed color discrimination. The Haitian Revolution was the most significant slave rebellion in world history and became, for slave owners, a frightening cautionary tale, told and retold everywhere Africans were held in bondage. For the Caracas cabildo, the conflagration in nearby Saint-Domingue, renamed Haiti, spelled imminent peril.

Simon Bolivar was eleven years old when a slave from Curacao appeared in Venezuela proclaiming "the law of the French," a dear

20 Americanos

reference to Haiti. The colonial authorities quickly snuffed out the ill-armed band of would-be liberators who responded to the call. To teach a moral lesson, the authorities severed the head of a free pardo who participated and dangled it in an iron cage on a twenty-foot pole, where passersby could stare at it for months. Another scare came a year later, in 1797, when three European Spaniards, deported from Madrid to the dungeons of La Guaira for their seditious activities, escaped with the help of a few French-influenced local radicals. The radicals' program included abolition of slavery, abolition of the Indian tribute, and free trade. The insignia of this new dawn was to be a multicolored ribbon symbolizing a rainbow coalition of white, black, pardo, and Indian. One of the participants betrayed the conspiracy, however, and it disbanded. Simon's uncle, Carlos Palacios, called it a conspiracy of la canalla del mulatismo, roughly "pardo scum." Naturally, the "scum" appealed to "the detestable principle of equality," he wrote to relatives in Madrid. This was just what they had warned the king about. 7

These anxieties were still in the air in 1802, when Simon Bolivar tried his hand at managing a sugar plantation and Maria Teresa tried hers at being a plantation mistress. If the young couple feared their slaves, however, they need not have. Maria Teresa's vulnerability to the unfamiliar environment, not a pardo uprising, was their undoing. Maria Teresa got a tropical fever that rapidly worsened. Simon frantically transported her to Caracas, where she died in January 1803. Their idyll had lasted for a very few months. Dejected, Bolivar decided to return to Europe immediately.

Humboldt Inspects Peru and New Spain

Humboldt and Bonpland were headed toward New Spain in January 1803, when Maria Teresa died. To amuse himself on the northward voyage along the Pacific coast of South America, Humboldt did his usual sampling of seawater and currents. In so doing he became the first to measure a major global phenomenon, now called the Humboldt Current, a sort of Gulf Stream in reverse that conveys frigid polar waters toward the equator.

During 1802, Humboldt and Bonpland had investigated Inca history in Peru and become fascinated by the great Andean heartland of indigenous America, with its farming villages where Quechua, the language of the Incas, remained the normal language of conversation. In Peru, Humboldt's imagination was fired by works of Inca engineering,

especially the system of paved roads, as many as ten thousand miles of them, still partially in use. The Prussian pronounced them as good as those constructed by the ancient Romans. Examining the bird manure fertilizer called guano, which the indigenous farmers had used since ancient times to maintain the fertility of their garden terraces, Humboldt found it superb and recommended its use in Europe. (When European farmers eventually tried guano years later, they bought twenty million tons of it.)

Resting in Lima, Humboldt wrote one of the rare letters to his brother that actually found its way across the Atlantic. He mentioned highlights of the last few months: the ascents of Pichincha and Chimborazo and his examination of a manuscript in a pre-Incaic language. At this point Humboldt had studied several indigenous languages and argued that they had wrongly been called "primitive." Humboldt was developing an intellectual case in favor of America's indigenous people. During the Peruvian leg of his journey, Humboldt became firmly convinced that "a darker shade of skin color is not a badge of inferiority." 8 It was the Spanish conquest, he affirmed, that had caused the misery in which Indians now lived. Humboldt described Indian porters who earned a pittance carrying travelers on their backs over Andean ridges in New Granada for three or four hours a day. Outraged by the symbolism, he and Bonpland had refused to ride on the backs of these men. But the porters, as it turned out, did not appreciate the moral support, being more concerned about their loss of earnings. Humboldt and Bonpland paid for their gallant gesture in more ways than one, as torrential rains sent water cascading down the rutted, rocky trails, soaking their boots, which eventually tore apart, leaving their feet bare and bloody.

Humboldt heads a long line of European travelers who detested nineteenth-century Lima. Lima mentally faced its seaport and the world beyond, turning its back on the Andes and the Indian majority who spoke Quechua, believed Humboldt. It was a stronghold of Spanish royal and ecclesiastical bureaucracy, not an Andean city at all. He was right. Lima had been one of the first viceregal capitals in America. In the 1600s, the rich silver mines at Potosi made the name Peru synonymous in Europe with fabulous wealth. But Potosf's "mountain of silver" stands (at the highest inhabited altitudes on earth) in L T pper Peru (modern Bolivia), and when, in the 1700s, the Spanish crown created two new viceroyalties, Upper Peru (and with it, alas, PotosO was removed from Lima's jurisdiction. Lima never really recovered from the loss of Potosf. In Humboldt's day, Lima still looked impressive

22 Americanos

from just outside the city, where one could see its dense clusters of churches and convents, testimony to bygone splendors. The greatest jewel in the Spanish imperial crown now was unquestionably no longer Peru but New Spain, where Humboldt, Bonpland, and Carlos Montufar landed in March 1803.

Humboldt's first, diplomatic thought upon landing at Acapulco, New Spain's principal Pacific port, was to write a letter to the viceroy announcing his arrival. By this time, he could do so without help in elegant, formal Spanish. He put himself at His Excellency's disposal, offering expressions of profound respect, praising His Excellency's reputation as a protector of utilitarian arts and sciences, and providing His Excellency a full itinerary of the places he had visited in America.

Overall, New Spain struck Humboldt as a far more developed colony than anything south of it. New Spain was the most populous, prosperous, and profitable of all Spain's American possessions, producing about half of all colonial revenues for the crown. Here Humboldt devoted himself to something he had promised the king of Spain: evaluating colonial mining techniques. Humboldt's many-faceted expertise included formal training in mineralogy. Humboldt being who he was, he saw room for improvement in New Spain, but less in the mines than in the overdependence on mining itself. For centuries, the Spanish crown had privileged the great silver mines of Peru and New Spain, organizing its entire American empire to serve mining interests. Given the fabulous wealth of these mines at their height, one can see why. At the time of Humboldt's visit to Guanajuato, north of Mexico City, a single mine there, the Valenciana mine, was responsible for fully one-fifth of all world silver production. The 20 percent tax on minted silver had been the Spanish crown's chief economic interest in America for centuries.

But Humboldt thought that the fertile lands of New Spain could produce even more wealth than its mines and employ more people, too. Employing people seemed urgent, because economically marginalized indigenous farmers composed half the population of New Spain. From a different perspective, "marginalized" Indians were enjoying reliable subsistence agriculture. Many of them, in fact, saw it just that way. Overall, indigenous people, accustomed to providing for their own needs, showed little interest in trade or in wage labor. Humboldt argued, however, that if Spain did not want to lose its colony, "the copper-colored race" would have to be better integrated into it and share the prosperity. Otherwise, he explained, there could be more bloody indigenous uprisings such as Peru's Tupac Amaru rebellion of the

1780s. That rebellion was the largest ever to occur in colonial America. Tens of thousands died. Once they had repressed the savagery of the rebels, the Spanish applied their own, pulling Tupac Amaru apart, limb from limb, before a jeering crowd and distributing fragments of his corpse as gruesome warnings about the perils of rebellion.

Enter Father Hidalgo

In New Spain Humboldt found people who shared his critique of Spanish imperialism, though he did not meet a dissident priest named Miguel Hidalgo. Hidalgo shared many interests with Humboldt and would have delighted in hosting our travelers. Besides, Hidalgo lived not far from the silver mines of Guanajuato, the greatest ones in New Spain, which Humboldt intended to visit.

Father Hidalgo agreed with Humboldt that diversification was essential to the economy of New Spain and that "the copper-colored race" needed opportunities to prosper. And like Humboldt, he pondered many sorts of practical innovations, things that could provide gainful employment for the Indians and mestizos. He proposed to plant some olive trees and also some vineyards. Why import olive oil and wine from Spain if New Spain could produce them? The practical answer was that Spain's monopoly trading system prohibited the colonies from competing, but Hidalgo had no patience for that. He proposed to plant mulberry trees, because he wanted to cultivate silkworms, which feed on those leaves. Breaking the profitable Chinese monopoly on silk manufacture was then being attempted in various places. Why not New Spain? Local clay would produce good pottery, and Hidalgo had specific ideas about what kinds of pots to make and sell. The rich mining city of Guanajuato would provide a nearby market, an important consideration because pots are heavy to transport. A tannery made good sense, too. After all, domestic animals were slaughtered every day for food; why not tan the hides for use as leather? In addition, one could always consider textile manufacture—on a small scale, of course, and utilizing wool; who could afford cotton? Hidalgo envisioned these as enterprises that would be owned and worked in common by the people of the village. They would produce for the market, but the organization of production would be communal rather than capitalist.

Hidalgo's friend Manuel Abad y Queipo, recendy selected as bishop of Michoacan, would have loved to meet Humboldt as well. Abad y Queipo had gained some notoriety in 1799 by writing a letter of pro-

24 Americanos

test to the Spanish crown. Abad y Queipo explained that nine-tenths of the people of New Spain, by his estimate, were Indians, and poor mestizos and pardos whose destitution gave them no investment in the colonial order. They resented the whites who had everything while they had nothing. The Indians protested at the special tribute they had to pay, while mestizos and pardos chafed at the caste system that limited their social mobility. Among the bishop's recommendations were elimination of the tribute and caste distinctions and free distribution of all the vacant lands in New Spain. The bishop's main recommendation, though, was more royal support for the church, most especially for the parish clergy. Only the parish clergy, according to Abad y Queipo, could exert the moral suasion needed to maintain Spanish rule in the villages of New Spain. Abad y Queipo and Hidalgo sometimes discussed such topics, as well as French books and "utilitarian arts and sciences" such as silk production, in which both had a special interest. The two were old friends.

Lately, though, the bishop had been concerned to hear that Hidalgo was under investigation by the Holy Inquisition. The investigation stemmed from indiscreet remarks made at a gathering in 1800. Hidalgo had supposedly declared disbelief in Christ's virgin birth. Hidalgo's educational views, too, were branded unorthodox—influenced by the French thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Hidalgo had supposedly declared himself in favor of "French liberty." In fact, his house in the parish of San Felipe had acquired the nickname "Little France" because, according to witnesses, Hidalgo gathered all sorts of people there in a spirit of equality, without due attention to caste distinctions or social hierarchies. Hidalgo's legendary parties at Little France included dancing, theatricals, and card playing, as well as serious discussion. Hidalgo made fun of church rituals and incense, discovered the inquisitors. His assistant, another French-reading radical priest who often substituted for Hidalgo at mass, had to be alert for his superior's practical jokes. On more than one occasion, when the faithful were already kneeling, the assistant found that Hidalgo had hidden the communion wafers. In addition, Hidalgo declared fornication to be not so bad, and he put that conviction into practice. Over the years, he lived with several women who bore him children. Josefa Quintanilla, one of these women, commonly appeared with leading roles in the theatricals that Hidalgo liked to stage at his house from time to time.

Abad y Queipo did not approve of all this, obviously. He had watched Hidalgo's behavior destroy a promising academic career. A boy from a middling family of espanoles americanos, the son of the

administrator of a rural estate, Hidalgo had gone away to school at the age of twelve. He excelled, and for the next twelve years immersed himself in Latin literature, rhetoric, logic, ethics, theology, Italian, and French, as well as two indigenous languages, Nahuatl and Otomf. Despite certain escapades and a nickname (elzoj~ro, "the fox") that gave a hint of his future trespasses, the well-liked Hidalgo gradually rose to become the rector of his school, one of New Spain's best, San Nicolas College in the provincial city of Valladolid.

Hidalgo immediately tried to modernize the curriculum and texts of San Nicolas College, moving away from a medieval-style focus on rhetoric, logic, and theory toward a focus on applied, practical knowledge. Given the large personal investment of the college faculty in the old subject matter, reform was an uphill battle. Still, to that point, Hidalgo's academic career had been a smashing triumph, one that brought sufficient financial reward to enable the purchase of considerable property. But then Hidalgo's fast living caught up with him. He mismanaged college funds and developed a large personal debt, probably betting on cards, one of the most popular pastimes in colonial New Spain. His enemies at the college demanded his ouster, and given the untidy details of Hidalgo's personal life (which included a son and a daughter), they succeeded in forcing his resignation in 1792. Since that time, Hidalgo had spent a decade as parish priest in the town of San Felipe.

As Humboldt and Bonpland made their way from Acapulco to Mexico City, Hidalgo was preparing to leave San Felipe and move to the nearby village of Dolores, a smaller, poorer, more Indian parish. In Dolores, he would have a chance to try all his projects—the silkworms and vineyards and olive orchards, the looms and pottery and tannery. Miguel Hidalgo was then fifty years old, already completing an average life span for his day, and he looked older still. He was a bit weary of all the partying and wanted somehow to make a difference in the world. He must have believed, as he moved his household (including his companion Josefa Quintana and their two children) in creaking carts to Dolores in August 1803, that he was opening his life's final chapter. But the book had an ending he couldn't foresee.

Considering Liberty and Tyranny

In August 1803, Humboldt and Bonpland were no more than a days travel away from Hidalgo, visiting Guanajuato and its mines. Hum-

26 . Imericanos

boldt had spent 1803 busily visiting mines and collecting economic and demographic data in New Spain. New Spain was another great heartland of indigenous America rather than a frontier to be explored— except, that is, for the extensive and sparsely populated provinces of the distant north, including Texas and California. Humboldt spent his time in New Spain's offices and libraries rather than tromping through the wilderness. Mexico City, the third viceregal capital on his tour of America, was by far the most impressive. Large, prosperous, bustling, spaciously planned, with imposing public buildings, Mexico City was in fact one of the most impressive capital cities anywhere, which it had been since Aztec times.

But Humboldt and Bonpland were now eager to return to Paris. First Humboldt wanted to visit the United States, however. He hoped, above all, to meet the U.S. president, Thomas Jefferson, whom he fervently admired, and so he wrote to Jefferson (in French) immediately upon landing in Philadelphia. The travelers did not have to wait long for Jefferson's enthusiastic response. Jefferson had a special interest in the geographical data Humboldt had gathered in New Spain. As president, Jefferson's grand gamble was the Louisiana Purchase—a huge tract of the North American continent that doubled the territorial claims of the young United States overnight. Jefferson had bought the territory from Napoleon, who needed money and had his hands full in Europe and in Haiti, where rebellious former slaves led by Tous-saint Loverture and his successors had decimated several large French armies. The Louisiana Purchase bordered Texas, a northern province of New Spain, but the border was entirely theoretical and still largely uncharted and unmarked in 1804, when Jefferson received Humboldt's visit. The Lewis and Clark expedition had embarked to explore the Louisiana Purchase a few weeks earlier. They would not return for years. Hence an invitation to Jefferson's county estate at Monticello.

Humboldt traveled through a still half-built Washington, D.C., to the ridges of western Virginia, where he and Jefferson talked animatedly about the emerging map of the United States. They doubtless spoke as well of their shared conviction that the New World constituted a space where liberty would create a better society. In 1804, liberty was a very important word, one that no longer has the same ring it once did. As a big idea, liberty implied the freedom to exercise rational self-interest, free from arbitrary governmental interference or tyranny. Humboldt believed that the United States understood liberty—with the glaring exception of slavery in the southern United States, of course. The first American republic had made a portentous entrance

onto the world stage. It had enjoyed favorable European trade and weathered a series of political crises, the election of "French-loving" Jefferson being the greatest of these. Humboldt took note, and back in America, so did people such as Hidalgo. But the U.S. example did not appeal to many of Hidalgo's countrymen. After all, English-speaking Protestants had been enemies of Spanish-speaking Catholics for centuries. America's freethinkers admired England and the United States, but they tended to feel more passionate about the French Revolution.

By August 1804, Humboldt and Bonpland were in Paris, where they (or rather Humboldt, always alone in the spotlight) met wonderful acclaim. At that moment, only Napoleon was more famous in Europe than Alexander von Humboldt. Napoleon seemed not to relish the competition. After Napoleon crowned himself in Notre Dame Cathedral, Humboldt attended the coronation gala and congratulated the new emperor, only to be snubbed by him: "I understand you collect plants, monsieur. So does my wife." 9 The idealistic early phase of the French Revolution was now over.

Simon Bolivar, too, was in Paris during Napoleon's autocorona-tion, distracting himself from the grief of Maria Teresa's death, often in the company of her wealthy kinsman Fernando Toro. In the heady atmosphere of the French capital, the young Venezuelan was undergoing a political metamorphosis, becoming an exponent of liberty. At stylish gatherings, he spoke in impassioned tones about Spanish tyranny and about creating new republics in America. When Humboldt and Bolivar were introduced in a Parisian salon, where elegant ladies and gentlemen gathered to socialize, Humboldt was not very impressed, but Bonpland liked Bolivar and encouraged him to keep thinking. Bolivar was raw at being a revolutionary, but it had given his energies a new focus.

A critical element of Bolivar's metamorphosis was the presence at his side of his former schoolmaster from Caracas, Simon Rodriguez, an in-your-face nonconformist, scornful of all social conventions. Rodriguez had fled Venezuela following the 1797 "French" conspiracy there, in which he was implicated. The freethinking schoolmaster escaped under an assumed name, Samuel Robinson, which he took from the book Robinson Crusoe to signal his self-reinvention as a political castaway. Rodriguez went first to Jamaica, where he improved his conversational English, then to the United States, and then, of course. to France, the original homeland of liberty, where he lived as "Samuel Robinson of Philadelphia" and shared a house, for a while, with Servando Teresa de Mier, a radical priest who had fled New Spain for

28 Americanos

political reasons. Rodriguez eventually traveled throughout Europe, learning more languages and trying his hand at a variety of trades. Rodriguez was a passionate exponent of Rousseau's educational theories, which emphasized practical experience and discovery over simple memorization of prepared lessons.

Shortly after meeting Humboldt in Paris, young Bolivar left with Rodriguez, now acting as his tutor and legal guardian, for an educational walking tour from France to Italy, a sort of crash summer-abroad course in the philosophy of liberty. While in northern Italy, tutor and student saw Napoleon in person, a defining moment in the life of Bolivar, who afterward was often compared to Napoleon. Perhaps he had Napoleon in mind when, weeks later, the young Venezuelan vowed amid the inspiring ruins of ancient Rome that he would free America from the yoke of tyranny. Also in Rome, Bolivar crossed paths again with Humboldt. Humboldt did not record his impressions of Rodriguez/Robinson, which is a shame. Instead, Humboldt hurried off to climb another volcano, Vesuvius, where he hoped he might be present at an eruption.

Jose Bonifacio Yearns for Brazil