CHAPTER 5

Incipit Vita Nova

1937

A thousand lovely fancies

Play upon my mind.

—Anonymous

WHEN GRACE FRICK ARRIVED AT the Hôtel Wagram on February 4, 1937, Marguerite Yourcenar was enjoying one of her usual winter stopovers there. As a writer, her star was on the rise. Having first stepped onto the Parisian literary scene with the critically acclaimed short novel Alexis in 1929, the thirty-three-year-old author had just published Feux, an extraordinary work depicting a certain “notion of love.”1 The beautiful short story “Notre-Dame-des-Hirondelles” had appeared in January, and the essay “Mozart à Salzbourg” would come out early the following month.2 Les Nouvelles littéraires would publish “Le Lait de la mort” in March.3 Two more stories and one essay would appear before the end of the year.

In Yourcenar’s personal life things were not going quite as well. The critical success of her writing had not made her a best-selling author. Her literary earnings were far from enough to live on in the fashion to which she was accustomed. The precious capital salvaged at the beginning of the 1930s from the estate of her Belgian mother’s family, the Cartiers de Marchienne, had shrunk over the course of a peripatetic seven years. She who had long had the means to travel freely about France, Italy, Greece, Switzerland, and Central Europe could not continue to do so indefinitely. The contract she had signed to translate into French Virginia Woolf’s most recent work, The Waves, was an attempt to ameliorate her financial situation.4

Where her intimate life was concerned, the 1936 work Feux is widely believed to have been a means of exorcising Yourcenar’s “impossible passion” for the homosexual editor and writer André Fraigneau.5 Yourcenar had also very recently broken off what she would later call a “seven-year relationship” with another man, probably André Embiricos, the communist son of a wealthy Greek shipping magnate. When asked what brought that liaison to an end, Yourcenar replied, “He was an extremely difficult man. And I was young. But I learned a great deal, and also in the trade.”6 She had spent the summer of 1935 cruising the Black Sea with Embiricos on a large commercial vessel belonging to the latter’s father. Yourcenar had contracted malaria and was recovering in Athens when Embiricos convinced her that she would get better only at sea.7

Grace knew none of this, of course, when, still reeling from her own sea voyage, she entered the dining room of the Hôtel Wagram and saw for the first time a young Frenchwoman with luminous blue eyes dining with guests across the room. According to Yourcenar years later, Grace had heard her talking to a group in the dining room of the hotel the day before they met and had been impressed by her manner of speaking: “Grace said to herself, ‘There’s a young woman who knows a lot about a variety of things and who is going somewhere.’”8

No one has ever been able to pin down precisely on what day Grace and Marguerite met. Josyane Savigneau places their encounter sometime after Yourcenar’s return from London to consult Virginia Woolf about The Waves.9 That meeting, chronicled in the essay “Une Visite à Virginia Woolf,” took place on February 23, 1937.10 Michèle Goslar opts for “one day in February 1937—probably the fifteenth.”11 But the late-life testimony we now have from both Frick and Yourcenar, along with detailed records kept every day and preserved by the Sisters of Sion, suggests that the women met earlier. From the house journal of Issy-les-Moulineaux, we know that Sister Marie Yann died on February 7. From Frick’s 1977 recording, we learn that Grace arrived in Paris three days before that death, on February 4, and that she first laid eyes on Marguerite in the dining room of the Wagram that same evening. Mme Yourcenar remembered in 1984 that Grace had first seen her in the hotel dining room the day before they met. All of which suggests that their first conversation took place on February 5.

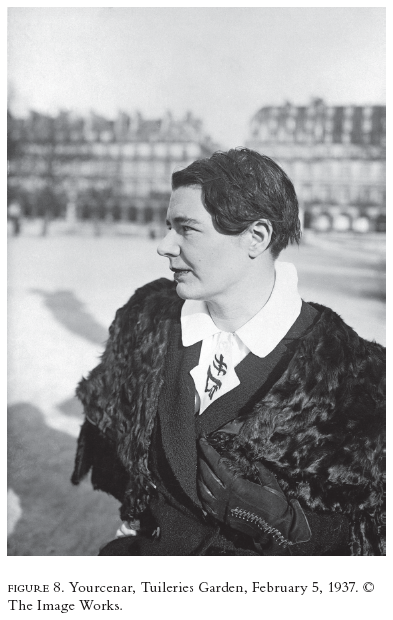

By fortuitous coincidence, three professional photographs, taken that very afternoon, show us exactly what Yourcenar looked like when Frick first laid eyes on her.12 The pictures were taken at the Tuileries Garden, across from the Hôtel Wagram, by the Parisian celebrity photographer Albert Harlingue. Hatless in one of the three, the young writer sports boyishly short-cropped hair and what seems to be a sealskin wrap around her shoulders. Because the photos are not in color, we can’t see what struck Grace first and foremost about Marguerite, her stunning blue eyes. But one can certainly see why she would have been intrigued.

The two women had a lot in common. They were born in the same year, 1903, five months apart. Grace’s birthday, January 12, was also the day on which Marguerite’s beloved father, Michel de Crayencour, had died in 1929. Alice May Frick, Grace’s mother, and Fernande de Crayencour, Marguerite’s, were both thirty-one years old when they gave birth to their only daughters.13 Grace and Marguerite had both lost a thirty-one-year-old parent the same year they were born. Both loved literature, art, the ancient world, and visiting museums. Both were avid travelers. Both had a deep fondness for birds and the natural world. Both were open to a same-sex romance. It’s no wonder they hit it off so famously.

On the morning after they met, Grace asked a bellboy to deliver a note to Marguerite inviting her to come see “lovely birds” on the roof outside the window of her room. It is hard to imagine that, gazing on those sparrows or starlings, Marguerite gave no thought to her just-published tale in which mischievously amorous nymphs, condemned by a Christianizing monk, are transformed into joyful young swallows.14 As Jerry Wilson put it in his journal, it was right then and there that Grace and Marguerite “became friends.”15

Michèle Sarde comments in Vous, Marguerite Yourcenar: La Passion et ses masques that Wilson’s “poetic” version of Yourcenar’s encounter with Frick

prophesies in a single metaphor the partnership with Grace in which you engaged for fifty years: an entirely inward relationship consisting of “looking together in the same direction.” The authoritarian American, even in the heart of Paris, summons you onto her territory to contemplate from the rue de Rivoli, not the rooftop vistas and the architectural splendors of the capital, but flights of birds. A prelude to the rustic existence, amid the animal world, that you would lead together on Mount Desert Island.16

Years later Yourcenar did not recall being “summoned” by Frick; rather, she remembered receiving “a pretty little card” of invitation. Her own next move was to take Grace to a Parisian nightclub.17 As one witness from the 1930s, André Fraigneau, told Josyane Savigneau, Yourcenar “liked bars, alcohol, long conversations. She was constantly seeking to seduce. . . . She was the very epitome of a woman who loves women.” But Fraigneau, who knew Yourcenar long before Frick arrived on the scene, goes on to observe that the young Frenchwoman “did not enjoy herself in cities; there was something rather wild about her.”18

Grace visited the Issy house three times in February to tend to her cousin’s affairs. On February 19 Yourcenar left Paris to meet Virginia Woolf, the “prominent contemporary English novelist” about whom Frick had written admiringly in her “Survey Unit for the Study of English Literature” at Stephens College. What a thrill it must have been to know someone who was translating one of her novels!

Woolf was less enthusiastic, as her published diaries reveal, about her visit with “the translator.” On Tuesday, February 23, she wrote,

That extraordinary scribble means, I suppose, the translator coming. Madame or Mlle Youniac (?) Not her name. And I had so much to write about Julian. . . . So I’ve no time or room to describe the translator, save that she wore some nice gold leaves on her black dress; is a woman I suppose with a past; amorous; intellectual; lives half the year in Athens; is in with Jaloux &c, red lipped, strenuous; a working Fchwoman [sic]; friend of the Margeries; matter of fact; intellectual; we went through The Waves. What does “See here he comes?” mean & so on.19

This fit of pique probably had less to do with “Madame or Mlle Youniac” than with Woolf’s well-known distaste for obligations that cut into her writing time. Yourcenar, in any case, was much more sympathetic toward Woolf. In “Une Visite à Virginia Woolf,” first published in 1937, she wrote,

Only a few days ago, in the sitting room dimly lit by firelight where Mrs. Woolf had been so kind as to welcome me, I watched the profile emerge in the half-light of that young Fate’s face, hardly aged, but delicately etched with signs of thought and lassitude, and I said to myself that the reproach of intellectualism is often directed at the most sensitive natures, those most ardently alive, those obliged by their frailty or excess of strength to constantly resort to the arduous disciplines of the mind.20

While Yourcenar was crossing the English Channel to meet Virginia Woolf, Phyllis Bartlett was crossing the same body of water in the opposite direction, traveling with one Phyllis Rothschild, to join Grace at the Hôtel Wagram. Bartlett, who first introduced Frick to the splendors of Paris in 1928, had recently completed her PhD at the University of Wisconsin. She was spending the 1936–37 academic year in London on a postdoctoral traveling fellowship.21 On March 8, 1937, Grace was back at Issy-les-Moulineaux. She would go to England for a few weeks doing literary research later that month.22 After visiting a Kansas City friend in Biarritz, Grace returned to Paris and prepared to set off with Marguerite.

About those glorious months which Grace and Marguerite spent discovering new places and each other, Josyane Savigneau has written that Yourcenar

played the “lovers’ journey” to the hilt with Grace: from Venice to Capri by way of Corfu and Delphi. There are no traces left of those first months spent side by side, except a photograph of Grace, in profile, in an unidentifiable place, and another one of Marguerite, probably taken by Frick, on the Piazza del Duomo in Florence. They are ordinary pictures that don’t reveal a thing. The photographs of Frick allow for only one observation: she was not very pretty.23

Savigneau’s negative assessment of Frick’s appearance has become almost an article of faith among Yourcenar biographers, journalists, and other commentators. Though buttressed by a number of unflattering photographs, the appraisal is not shared by all observers. One Frenchwoman who knew Yourcenar in the 1930s, the artist Charlotte Musson, had this to say years later: “Please remember me to Grace Frick, whose beautiful face I was struck by. I have spent my life painting or wanting to paint faces that, probably, escaped me. Joys and regrets.”24 Deirdre “Dee Dee” Wilson, who would be an American neighbor and close friend of Grace and Marguerite later in their lives, often speaks of Grace’s beauty, emphasizing her lovely, “doelike eyes.”25 Mme Yourcenar professed throughout her life to be attracted to “a certain human type.” As she remarked in 1983, “When I remember my preferences as far as dolls were concerned at the age of seven or eight, I see in them my present sexuality.”26 The tall, dark-haired André Fraigneau and André Embiricos, two male objects of Yourcenar’s desire in the 1930s, fit her type to a T. So too, with her luxuriously thick dark hair, did the tall, slim Grace Frick. She may not have been a stunning beauty like Yourcenar’s Greek “friend” Lucy Kyriakos, but Grace had physical appeal—let there be no doubt about it.

Marguerite Yourcenar’s passport from 1937, issued on May 19, helps us track the two travelers’ itinerary.27 Judging from the stamps it is possible to decipher, and from some later correspondence, the women set off from Paris in a leisurely fashion toward Lausanne, Switzerland. En route they stopped in Dijon, the historical capital of Burgundy, which Phyllis Bartlett had urged Grace to visit when she was in Paris the previous February. Grace wrote of Dijon and nearby Beaune to Paul and Gladys Minear in 1949, when they were trying to choose a French city to tour with their children. She and Marguerite had spent a Sunday afternoon poring over maps on the Minears’ behalf:

If you can afford, say three days in Dijon and its surroundings and five days in Paris as a bare minimum (a week is far better) you would have some idea of a very typical provincial region as well as of France’s capital city. Also you would see in Dijon a great center of medieval culture, especially in the arts, and the capital of a sovereign state which endured independent of France, and making a unit with Flanders, until the Renaissance.28

After Dijon they spent some time in Geneva, where Yourcenar had once audited one or two classes.

Yourcenar’s passport awaited her at the French Consulate in Lausanne, a city that was something of a home base for the young woman. Michel de Crayencour had died in a clinic there eight years earlier. Christine Brown-Hovelt de Crayencour, his third wife, still maintained an apartment on Lausanne’s avenue de Florimont, and Marguerite often stopped to see her amid her European comings and goings. On May 21 she visited Lausanne’s Banque Cantonale Vaudoise to withdraw funds for her trip. By May 24 she and Grace were crossing the border by rail into Italy. The long Mediterranean leg of their journey was about to begin.

The travelers’ first maritime destination, for which they would embark from the Italian port of Genoa, was to be Sicily, where neither Grace nor Marguerite had ever been. Although a swaying gangplank almost brought their journey to an end shortly after it began, Marguerite eventually managed to board ship, and the pair set sail for Palermo. The highlight of their stay in that city was, without a doubt, the rowdy performances of Sicily’s “sublime” marionettes.29 As Yourcenar wrote in a short essay the following year, these oversized puppets, maneuvered not by strings but by steel rods, bring the warlike fury of Japanese samurai and the fervor of medieval mystery plays to an ingenious series of heroic plots. Sicilians had gathered the twelfth-century chansons de geste that in France were now of interest only to scholars and infused them with riotous life. There was valiant Roland and beautiful Aude, along with traitorous Ganelon and plenty of infidels on whom to heap riotous scorn. For Yourcenar, who throughout her life joyfully remembered the colorful, costumed celebrations of saints and village rituals of her pastoral childhood, these folk art shows with their magnificently outfitted puppets were the stuff of myth and legend brought to life. For Grace, who loved children, youth, and every kind of theater, they were a revelation. The clamoring children of even the poorest sections of Palermo all somehow managed to scrounge up twenty centimes to buy a ticket to the marionettes: “A hundred children and young men, ranging in age from four to eighteen years, shout, laugh, cry, clap their hands, jostle one another in the bleachers or in boxes built into the wall, jeering at latecomers who, refused entry, try to force their way in through the theater’s single small window.” A “marvelous menagerie,” including horses decked out for battle, a snake, and a lion, along with one sad and one happy strain of hurdy-gurdy music, round out the elements of the three-week series of performances that recounts a whole “history of France.”30 What Marguerite Yourcenar finds most beautiful about the spectacle are the angels who swing down from on high at the end of a string, tremulous in their élan, to coax from the dead soldiers their souls. She no doubt remembered them when writing her first U.S. play, The Young Siren.

The couple’s first excursion in Sicily was to Segesta, an ancient Elymian city about seventy-five kilometers southwest of Palermo.31 Segesta boasts a superbly preserved fifth-century BCE Doric temple and a classical amphitheater.32 There being no tourist shuttle to the site, Grace, the avid equestrian, convinced Marguerite that they should make the three-kilometer trip from Calatafimi on horses. Yourcenar later spoke of that ride as one of her fondest memories, recalling, among other experiences from that summer with Grace, “a morning arrival in Segesta, on horseback, via trails that in those days were deserted and rocky and smelled of thyme.”33

In the opposite direction from Palermo, Grace and Marguerite set a course for another ancient city, Taormina, on the northeast coast of the island, stopping wherever fancy struck them along the way. Here again they were on the trail of a remarkably preserved teatro greco, this one Corinthian in style.34 Taormina was originally occupied by an early Sicilian tribe and later taken over in successive waves by Romans, Arabs, and Normans. From the mountainside theater, the two voyagers enjoyed an unimpeded view of Mount Etna and the Ionian Sea.

Crossing over to Villa San Giovanni on the mainland, the women eventually proceeded by train to Naples. Yourcenar had heard Adolf Hitler speak in that ancient maritime city with her father in 1922 and later made it the setting of the short story “D’après Greco.”35 Having first explored Naples with Michel, Yourcenar was eager to return there with her new friend. Grace quickly came to share Marguerite’s love of the southwestern coast of Italy. From Naples they took their time heading northward, making long stops in Rome and Florence, and shorter stops in smaller towns. In Florence, renowned for its artistic and architectural treasures, she and Grace took in everything from the Boboli Gardens to Michelangelo’s unfinished Pietà. Of particular interest to them were the fifteenth-century paintings and frescos of Fra Angelico, inspired by the life of Christ, at the church and onetime friary of San Marco.

The two travelers likely spent all of June in Italy, either on the west coast or touring other sites on the peninsula; no departures are recorded in Yourcenar’s passport until July 16, when they embarked at Venice on a cruise of the Dalmatian Coast. The next day their ship, the RMS Adriatic, made its first stop at the Yugoslavian port of Dubrovnik. From that city, known in Latin as Ragusa, Grace sent a postcard to Ruth Hall in New York City that featured long-skirted peasant women wearing headscarves at an outdoor clothing, fruit, and produce market. She was enthralled by the medieval aspects of Ragusa and the beautiful, richly colored native costumes with their heavy embroidery. “Our boat stopped for seven hours,” she wrote, “and as it was a festival day we saw a great deal both in the streets and from the city walls. We have a boat almost to ourselves and feel like kings.”36

On July 19 Grace and Marguerite landed on the Greek island of Corfu. Over the course of the next three weeks they would make Athens their base of operations, taking excursions by train or by car from there to various destinations: Thebes, a powerful ancient Greek city renowned for its association with Oedipus the King and Dionysus; Delphi, the sacred site of the female Earth deity Gaea during the Mycenaean period and later home to the temple and oracle of Apollo; Eleusis, seat of the Eleusinian Mysteries, which so fascinated the emperor Hadrian that he and his lover Antinoüs were initiated into them; and Cape Sounion, a promontory at the southeastern tip of the Attic Peninsula from which, according to legend, King Aegeus leapt into the sea to his death. All of these places were sites of spectacular beauty. Yourcenar would cherish the memory of these experiences throughout her life, including them among those she would like to see pass before her eyes at the moment of her death: “Cape Sounion at sunset,” she told Matthieu Galey, “Olympia at noon. Peasants on a road in Delphi, offering to give their mule’s bells to a stranger.”37 That stranger was Grace Frick, who received the bells from a peasant woman who had stopped to let her donkey drink from a spring.38

Shortly before leaving Greece, Grace and Marguerite attended another Mediterranean folk art performance, this one of the Turkish shadow theater, in a garden on the outskirts of Athens. Yourcenar was inspired to write about these plays, known by the name of their main character, Karagöz, as she had Sicily’s marionettes. Thanks to her essay, we can imagine what it must have been like that August night in 1937. For the outdoor show, a sheet is hung in the manner of a movie screen, and a small orchestra of flutes, guitars, and drums plays ancient popular music. The stage is thus set for the arrival of Karagöz, illiterate but wily, and his rival, the learned rich man. Old regulars and little boys make up the bulk of the audience. “Among children who are crunching on pistachios and connoisseurs savoring a Turkish coffee,” Yourcenar writes, “it is as if we are witnessing rites as old as the human imagination.”39

Accompanying Marguerite and Grace to this all-night show was a Greek acquaintance, Zoé N. Dragoumis. The fifty-five-year-old Zoé belonged to an important political family. Her father, Stephanos N. Dragoumis, had served as Greece’s prime minister and held other high posts. Shortly after attending the shadow play performance, Zoé gave an inscribed copy of Giulio Caïmi’s Karaghiozi, ou La Comédie grecque dans l’âme du théâtre d’ombres to her fellow theatergoers: “In memory of our delicious initiation to the rites of Karagöz in the night of August 5 to 6, 1937, Athens, August 7, 1937, Z.D.”40 That same day Grace and Marguerite departed the port of Piraeus for Naples. On August 9 they made a quick trip to Capri so that Marguerite could reserve the small villa, La Casarella, on the Via Matermania for the summer of 1938.

Three days later Grace boarded the SS Conte di Savoia, bound for home, at the maritime terminal in Naples. So too, despite her susceptibility to vertigo and distaste for gangplanks, did Marguerite Yourcenar.41 Could she not bear the thought of the two of them parting after all those weeks spent so intensely together? Or was it simply a matter of wanting to bid Grace goodbye in the privacy of her cabin? Whatever the case may be, she did not want their tête-à-tête to end. Marguerite immediately set about making arrangements to follow Grace to America. On September 18, from Le Havre, she too would board a ship bound for New York.

Ciro Sandomenico’s Il “viaggio di nozze” di Marguerite Yourcenar a Capri calls those spring and summer months which Grace and Marguerite spent touring southern Europe in 1937 a “honeymoon.”42 Though no recorded testimony or love letter exists to bear out Sandomenico’s implication, one precious memento from that lengthy excursion has been overlooked. At some point during their long, unhurried wanderings through Italy, almost certainly in early July, Grace and Marguerite purchased two identical gold rings.

In the art nouveau style popular at the turn of the twentieth century, those simple bands, with their sensuous floral swirls, now reside in the safe deposit box of the Yourcenar estate in Northeast Harbor, Maine. According to their hallmarks, the rings were fashioned of eighteen-karat gold in the Tuscan province of Arezzo, by Uno a Erre in the city of the same name.43

Marguerite may have taken Grace to Arezzo, located some fifty miles southeast of Florence and ten miles off the direct route from Rome, because it was the birthplace of the great Renaissance humanist Petrarch. Yourcenar had read Petrarch’s love sonnets in her youth and would later make that figure one of the historical models for the adventurer-poet Henri-Maximilien Ligre in The Abyss. Where better to make a pledge of love?

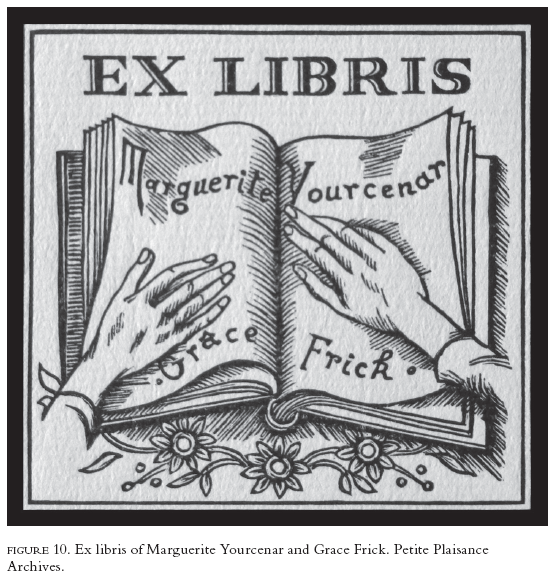

Whether the couple’s gold rings stood in fact for an intimate vow cannot of course be stated with certainty; but the ex libris designed at Marguerite’s request twenty-eight years later, now found in most of the volumes on the bookshelves of Petite Plaisance, features two thin bands, one atop the other, encircling the binding of an open book on whose otherwise blank pages appear the names Marguerite Yourcenar and Grace Frick.44 Laid across those fluttering leaves, as if to still them in a light breeze, is each woman’s right hand.45 Directly beneath the bound book, perhaps suggestive of the floral swirls on the gold rings themselves, is a simple garland of flowers.