CHAPTER 6

Passage to America

1937–1938

Ah! let me make no claim

On life’s incognizable sea

To too exact a steering of our way.

Let us not fret and fear to miss our aim

If some fair coast has lur’d us to make stay,

Or some friend hail’d us to keep company.

—Matthew Arnold

GRACE COULD HARDLY WAIT TO tell her friends about Marguerite. No sooner had she settled herself aboard ship than she dashed off a letter to her British friend Margaret “Daisy” Symons of Wormelow, Herefordshire. Grace had visited with Daisy, whose wealthy family bred racehorses in that English village, before returning to France to tour Italy and Greece with Marguerite. In 2012, the ninety-seven-year-old Herefordshire resident Cecil Miller remembered Symons, who died in 1949, as “a very masculine looking woman very keen on her horses.”1 Given Grace’s love of riding, one can easily imagine how the two became friends.

Frick’s letter to Symons has not survived, but Symons answered it on September 6, 1937, from Penllyn Castle in the Welsh village of Cowbridge.2 She and Grace had visited another Norman fortress together, Chepstow Castle, in southeast Wales during Grace’s spring trip to England. “Your letter written on board the Conte di Savoie interested me most deeply,” Symons writes. “In spite of uncomfortable Italian boats I envied you your tour and wished I was with you. . . . Please tell your friend Marguerite I would love to make her acquaintance either in Paris or Capri. I know for certain any real friend of yours would fill my soul.”

Back in the United States, Grace spent a few days with Ruth Hall in New York, where she wasted no time in calling her Wellesley classmate Florence Codman. Florence came away with the impression that Grace had fallen head over heels in love.3 Codman called Frick “a very brilliant student” and later, on meeting Marguerite, immediately grasped the allure of the Frenchwoman’s intelligence and bearing.

Yourcenar’s financial situation was somewhat at odds with her aristocratic manner, however. Yourcenar had been battling since 1928 to recover what was left of her maternal inheritance, which her half brother, Michel de Crayencour, had invested unwisely. To read the extensive correspondence between Yourcenar and her Parisian lawyer, Joseph Massabuau, you would think that she had spent the 1930s on the verge of financial catastrophe. Her letters grow increasingly anxious over that period, evoking everything from her stepmother’s medical expenses and cruelly inadequate income to her own fragile health and indebtedness. She nonetheless continued throughout the decade to patronize some of Europe’s most fashionable hotels, traveling routinely from Paris to Athens to Vienna in high style and throwing caution to the wind for several months while escorting Grace about the Mediterranean.

Nor was there any attempt to curtail expenses when she followed Grace to America in the fall of 1937. Sailing on the luxurious SS Paris, with its art deco and art nouveau decor, Yourcenar arrived in New York on September 25.4 She and Frick spent a week together in that city, at the elegant Barbizon Plaza Hotel on Central Park South, before proceeding to New Haven. Yourcenar was not charmed by New York City, finding that it lacked “French grace.”5 But the Barbizon Plaza, with its emphasis on the arts and artists, must have gone a good way toward smoothing the rough edges, at the same time it cushioned the transition between Mediterranean shores left so recently behind and the small Connecticut city of New Haven.

By this time Grace had rented a furnished apartment in a five-story brick building at 516 Orange Street, a five-minute walk from her former residence on Whitney Avenue and less than a mile from Yale University. She would remain there until September of 1939. Just in case some of Frick’s friends had not heard the big news, on October 9 the New York Times society column for New York and Connecticut announced that “Miss Grace Frick of New Haven is entertaining Miss Marguerite Yourcenar, French author.”6

Indeed, entertainment may have taken precedence, where Grace was concerned, over any sustained attention to her dissertation on George Meredith’s poems. And entertainment, first and foremost for her and Marguerite, meant travel, though it also apparently included attendance at a Yale football game. As Yourcenar wrote about America to Emmanuel “Nel” Boudot-Lamotte in Paris, “‘Indian summer’ is remarkable; the landscape in autumn sports the livery of the Redskin, the copper-tinged epidermis of Atala. And it is also football season now, which, in this country, partakes of carnival, the circus, and Bastille Day.”7 New England’s most colorful and poignant season also provided the decor for several trips to nearby Massachusetts. Of course, Grace took Marguerite to Wellesley, where they visited the bucolic campus of her alma mater as well as Grace’s several friends who were still teaching there. They also went to Lexington and nearby Concord, site of the first military battle of the American Revolution. Of more interest to Grace in Concord would have been Walden Pond, where the transcendentalist philosopher and antislavery activist Henry David Thoreau spent two years in the mid-nineteenth century communing with nature. The importance that Thoreau placed on frugality, living simply, racial justice, and the natural world resonated strongly with Grace. As Bérengère Deprez has shown, Thoreau became one of Yourcenar’s “main American inspirations.”8 The women also visited the culturally vibrant town of Northampton, home to Smith College, where Grace’s friends Charles and Ruth Hill had been teaching since 1932.9 One place they pointedly did not go together—whether then or at any other time—was to Kansas City to visit Frick’s family.

Grace eagerly introduced Marguerite to her Yale friends. Alice Parker shared Grace’s love of Shakespeare and her sense of social justice; several years before the civil rights movement began, Parker would give a series of talks in England promoting the importance of racial fairness.10 Yourcenar later called Alice “one of my first American friends” and spoke of “her generous optimism regarding human nature and at the same time her courageous lack of prejudices. . . . Through her one could touch the great America of old, which does not mean that she was not thoroughly and admirably concerned with contemporary problems.”11

Another friend, Mary Hatch Marshall, wrote a remembrance of Yourcenar in 1937. To Marshall’s mind, Grace was not hosting her French friend in high style: “All I remember of first meeting Marguerite, in that shabby little Orange Street apartment in New Haven, was the image of an attractive dark-browed young French woman, with a light accent, which she never lost—and an immediate impression of charm, intelligence, and very blue eyes.” Marshall went on to call Marguerite “vivid, lively, energetic, and beautifully dressed.” Grace, for her part, was “the kindest and most generous of women, with a slightly offbeat intelligence—a bit eccentric, more than a bit compulsive. She loved literature, was interested in problems of style, and willing, as Marguerite Yourcenar wrote, to discuss matters of phrasing again and again, with total concentration. She had great physical energy, and was a strong swimmer, swimming recklessly far out to sea, I remember.”12

Two more friends from that era mentioned by Marshall “taught at Hunter College and were both of distinguished mind and sensibility—Katherine Gatch and Marion Witt. Like Grace Frick, Katherine Gatch was a Wellesley graduate. . . . These friends had a car, and from time to time would drive Marguerite Yourcenar and Grace Frick on jaunts into the country. I well remember hearing how entranced Marguerite was by a field of wild flowers.”13

The relative inelegance of Grace Frick’s apartment may have intensified Yourcenar’s sense of penury. By midwinter her attempts to recover funds from her mother’s estate had shown no sure signs of success. On February 5, 1938, she reported in the exaggerated fashion characteristic of her letters to attorney Massabuau that she had so strictly reined in her expenses that her life in New Haven resembled “that of a cleaning woman and a librarian.”14 Yourcenar had been reduced to borrowing not only from a Swiss bank but also from the “American friends”—a masculine noun in her original French—with whom she was staying. Though she was of course neither cleaning houses nor manning a circulation desk, her distress was undoubtedly genuine. Writing to her lawyer from her stepmother’s apartment in Lausanne in January of 1935, Yourcenar had already described herself as “extremely tormented” by her financial predicament.15 Three years later she announced that if she didn’t receive at least part of the sum she was owed within two months, she would have to sell some of her stocks!16 While this was not a pleasant prospect during the recession of 1937–38, it should not go unnoted that she nonetheless had stocks to sell.

What Frick’s financial circumstances were at the time is hard to say. She was obviously able to help Yourcenar out, but Marshall’s description of the Orange Street apartment certainly suggests that she wasn’t living in luxury. She was a graduate student, after all, and she likely still received support from the LaRues in Kansas City. Unlike Marguerite, whose father had gambled away an inherited fortune, Grace had been raised in a family whose wealth, while substantial, was the fruit of its own industry. She was known throughout her life for her generosity, but Grace knew how important it was to manage her money with care. Every penny saved on daily living was a penny she could put toward the passion for travel that she and her friend shared.

Fortunately, one of Grace and Marguerite’s activities during those months in New Haven did not cost a cent: patronizing Yale’s outstanding libraries. Frick, of course, was working on a doctoral dissertation. Yourcenar, for her part, was discovering how much more accessible U.S. libraries were than those she frequented in Europe. In one interview conducted long after her financial troubles had been solved, she acknowledged their importance. American libraries, she said, “serve the public so much better [than French ones]. At Harvard and at Yale, for example, there are a great number of books available to a writer without a great deal of expenditure of his time. In France, it would have taken much effort to do the research I did while writing Hadrian.”17 In fact, Yourcenar did some of the reading for that crucial book as early as 1937 in the extensive collections available at Yale.18

Yourcenar was also engaged in another project, one she hoped would supplement her literary and investment income. It was a translation into French of Willa Cather’s 1927 novel Death Comes for the Archbishop, which many consider to be that author’s finest work. The book may have held particular interest for Yourcenar, as it was based on the lives of the first French missionaries to enter New Mexico, a former Spanish territory. According to a letter that Cather wrote to the American critic Alexander Woollcott in 1931, Woollcott helped her see that “the underlying theme” in Death Comes for the Archbishop and another of her novels was “a certain moral [gravity] in the French people.”19 But the project did not go smoothly, though Yourcenar did meet with Cather in New York to talk it over. By mid-March 1938 she began requesting a series of extensions of the deadline for completing the French text.20

In late April a Monsieur Delamain from Éditions Stock tried with considerable insistence to establish a firm completion date of August 1 for the manuscript, even offering to pay Yourcenar for incremental submissions in the interim. On May 4 the situation grew more urgent. “Excuse me for bombarding you on the subject of Death Comes for the Archbishop,” Delamain wrote again.

Rightly or wrongly, it turns out that the author is very worried about the translation and has had her dander up a bit in that regard since the meeting you had with her. We have in hand a long letter in which she protests quite vigorously against your refusal to use Spanish terms to describe things that cannot otherwise be rendered understandable and your intention to “paraphrase” those descriptions though you have not “the slightest knowledge” of the American region in question. . . . What it boils down to is that Mrs. Willa Cather wants to review a copy of the translation prior to any publication. Furthermore, the powers that be are proving to be absolutely intransigent with regard to the deadline of October 30 at the latest.21

In view of that deadline, the principals at Stock asked Yourcenar to send them as much of the manuscript as she had completed. They would then hire a speedy translator to finish it. To sweeten the offer, they promised her the contract for Frederic Prokosch’s novel The Asiatics, which Yourcenar had brought to their attention. It was merely a question of reaching an agreement with the English publisher.

Yourcenar submitted 253 of the novel’s 303 pages to Delamain. Cather rejected them outright. As for The Asiatics, Stock subsequently wrote to say that they had gotten mixed reviews of the novel and were hesitant to publish it. In the end, not surprisingly, they didn’t.

Cather later criticized Yourcenar’s translation in a letter to the director of Houghton Mifflin from, of all places, the Asticou Inn in Northeast Harbor, Maine. To Ferris Greenslet Cather wrote,

In my bookcase at home, I have translations of Death Comes for the Archbishop in nine different languages, and of the nine translations the one in Italian is much the best. One might think that the French translation would be very good, but I had to send back to the French publishers the first translation because it sounded like a school girl’s exercise in French and, above all, because the footnotes explaining Western terminology were incorrect and absurd. “Trappers,” for instance, in the footnote appeared as “a religious order.” I suppose the eventual French translation is better, but I have never had the heart to examine it very closely.22

Yourcenar was always noted for translations that, while beautiful, were not scrupulously faithful to the original texts. Constantine Dimaras, for example, often struggled with her over Constantine Cavafy’s poems: “Marguerite Yourcenar, as I think everyone today is aware, was rather authoritarian. And stubborn. I, for my part, had some very specific ideas about what a translation should be. She did not share these ideas. My view of translation is not at all lenient. I don’t like the idea of ‘euphonious inaccuracies.’ Marguerite, for her part, was solely concerned with what she thought sounded good in French.”23 Echoing Dimaras, Françoise Pellen, in “Translating Virginia Woolf into French,” calls Yourcenar’s rendition of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves “beautiful and a pleasure to read,” adding that as a translation it is “deeply, almost insidiously, unfaithful to the original.”24 Yourcenar’s deviations from Woolf’s original text were eventually considered significant enough to inspire Cecile Wajsbrot to undertake a new, more faithful translation in the early 1990s. Nevertheless, when an important new collection of Woolf’s fiction was published in France in 1993, Marguerite Yourcenar’s translation was chosen over Wajsbrot’s.25

Given the widespread perception of the beauty of Yourcenar’s translations, to say nothing of the highly sophisticated, stylistically polished prose she was composing in her own name during the mid- to late 1930s, it is hard to imagine that there was anything schoolgirlish about the language of L’Archevêque va mourir.26 But one can speculate about what might have rubbed Cather the wrong way. Yourcenar was a boyish-looking thirty-four-year-old with short-cropped hair when she met Willa Cather in the spring of 1938. Her often-noted air of self-assurance could sometimes be interpreted as Gallic hauteur. Cather, who would soon turn sixty-five, was already entering what Andrew Jewell has called the “misanthropic years” late in life when she became increasingly obsessed with protecting her image. With Edith Lewis’s assistance, as Jewell goes on to say, Cather is widely known to have “systematically collected and destroyed all the letters she could find in order to prevent undignified exposure to the rotting world.”27 Her most flagrantly “undignified” years were likely those when, with the audacity of youth, she identified herself as William Cather, favored suits and ties over more feminine attire, and wore her hair in a brush cut. Yourcenar may simply have been much too vivid a reminder of a persona whose traces the aging Cather was trying to erase. Death Comes for the Archbishop did not come out in French, translated by M. C. Carel, until 1940.28

Neither the Cather debacle nor Yourcenar’s financial distress prevented her and Frick from setting off on a tour of the U.S. Southeast. In March of 1938 the two women traveled to Georgia and South Carolina, where Yourcenar first became interested in Negro spirituals, the original music of America’s African slaves. Twenty-six years later, as racial tensions reached a fever pitch in the United States, she would publish Fleuve profond, sombre rivière, containing an important essay on the history and condition of American blacks, along with her translations into French of a wide variety of Negro spirituals.

En route home from the Deep South, Frick and Yourcenar made their first trip to Virginia, visiting Charlottesville, Richmond, Jamestown, and York.29 Marguerite would be returning to Europe in late April, and Grace did not want her friend to leave America without seeing the home of one of its founding dissenters, Thomas Jefferson. Writing about the experience years later, Yourcenar spoke of “the great president imbued with the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment” who had traveled to Italy and France and whose neoclassical residence outside Charlottesville resembled an Italian villa.30 As she noted in the documentary Saturday Blues,31 it was at Monticello that Yourcenar had one of several memorable encounters with American blacks. While walking up the hill toward Jefferson’s historic home on a rustic, tree-lined lane, she encountered an old black man in ragged clothes. Standing there motionless, he was listening to the trilling of a bird with an expression of rapture on his lined face. Yourcenar asked him what kind of bird it was.

“Why, honey, it’s a mockingbird,” the man replied.

It was the first time she had ever observed such a “capacity to enjoy life through every sense, as if through every pore. . . . Andersen’s Emperor of China took no more pleasure from his nightingale than did this probably jobless black man from his mockingbird.”32 Yourcenar saw in him a way of experiencing the world that was fundamentally different from her own European sensibility, and she never forgot it.

Finally, in early April, the welcome news arrived that 300,000 of the 500,000 Belgian francs that Yourcenar was owed from her mother’s estate had been deposited into her account.33 She had already purchased her return passage to Europe, where her latest book, Les Songes et les sorts, was about to be released; but the receipt of these funds meant that she could pay back the American “friends” who had kept her financially afloat and take one more trip before departing. Yvon Bernier provides a detailed description of that trip in his contribution to Les Voyages de Marguerite Yourcenar.34

On the evening of April 25 Grace and Marguerite dined at the New Haven home of Frederic Prokosch, whom Grace first met in the English department at Yale in 1931–32. After dinner, they boarded a train bound for Montreal. It was a particularly warm and verdant spring in Connecticut, where early wildflowers were blooming and the trees were lush with new foliage. The two women had taken several leisurely drives through the awakening countryside. In Canada, by contrast, it was bitterly cold. Crossing the dreary plain between Montreal and Quebec City, as Yourcenar wrote in an unpublished notebook, she and Frick found “trees without buds, plants with not a single leaf,” a landscape that was “hard and sad.” Upon arriving in Quebec, they took a room at the historic Hotel Clarendon within the walls of the Old City. From there they visited Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré, an important pilgrimage site. Yourcenar was particularly struck by an atmosphere of oppressive Catholicism, which held no appeal for either her or Frick. She found Quebec’s churches—fifty-seven of them—“ugly and overwhelming.” The next day, after a taxi ride around Quebec, the couple took the last train out of the city.35

Their spirits rose once they were on a train heading home. At lunch on the Canadian Pacific, they had a “sweet, lighthearted conversation about everything.” But Yourcenar regretted “having squandered in too hasty a jaunt three days we could have spent peacefully in some New England inn among the spring flowers and foliage.”36 Her state of mind may also be reflected in the repeated occurrences of the word “sad” in the few lines from Yourcenar’s notes about this trip that are cited in Bernier’s article: everything from Quebec’s landscape to its silver foxes to the Citadel’s glacis is seen through the same gloomy lens. One begins to wonder if her imminent departure was casting a pall over Marguerite’s last few days with Grace.

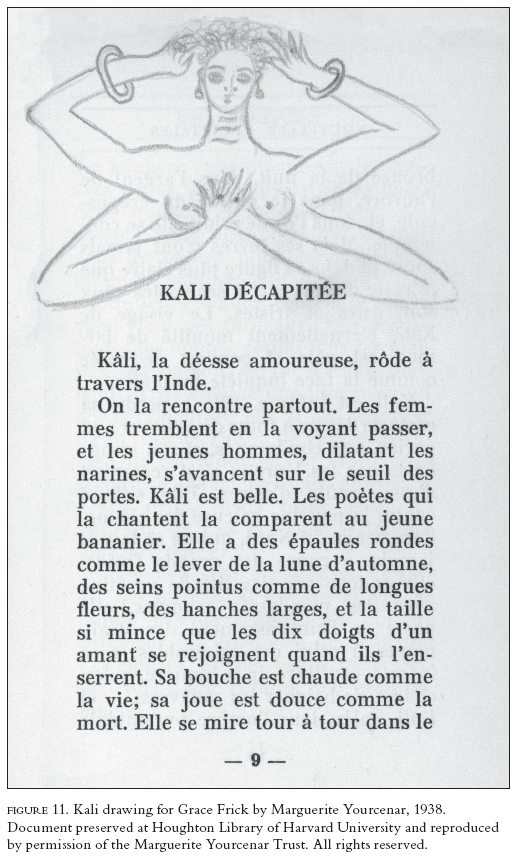

Yourcenar would leave on April 30, 1938, returning not to France but to Naples on the same Conte di Savoia that Grace had taken back to New York the previous August. Before sailing, she bestowed a unique gift on her American friend, a copy of her latest book dedicated to Grace and adorned throughout with her own hand-drawn illustrations. Nouvelles orientales had come out in Paris in mid-February 1938. It was a collection of short stories based on Balkan and Asian myths and legends. Sue Lonoff de Cuevas has interpreted the drawings that Yourcenar created for Frick in her fascinating Marguerite Yourcenar: Croquis et griffonnis. In the original edition of Nouvelles orientales, the story “Kâli Décapitée” came first. As Lonoff notes, the placement of “Kâli” at the opening of Nouvelles orientales “in itself is suggestive: all of Marguerite Yourcenar’s books from that period—Alexis, Feux, Le Coup de grâce, even parts of Denier du rêve—investigate a troubling sensuality. She herself suffered from an unrequited love yet also indulged in erotic adventures, including one with a married woman, at least until she made a more permanent commitment. In the dedication she added to this copy, she celebrates her new liaison . . . and perhaps she also playfully alludes to it” in the image drawn for Grace on the title page of “Kâli Décapitée.”37

In Yourcenar’s tale, based on Hindu myth, the once perfect and beautiful goddess Kali has been set upon by jealous gods who cut off her head and attach it to the body of a prostitute. Kali is now intellect and flesh, saintly and profane. She roams the earth, as Lonoff recounts, “condemned to copulate with all who desire her.”38 Yourcenar’s text describes Kali’s shoulders as “round like the rising autumn moon; her breasts are [pointed] like buds about to burst. . . . Her mouth is as warm as life. . . . But her lips have never smiled; . . . and upon her face, paler than the rest of her body, her large eyes are pure and sad.”39 But, as Lonoff observes, Marguerite’s drawing of Kali is often at odds with her textual description:

Kali’s kohl-rimmed eyes gaze directly at the viewer, and her rudimentary mouth reveals no sign of anguish. The small head is out of proportion to the arms, which angle out to offset the torso’s roundness. The hands that flutter in the wiry hair are prominent and active. The lower arms are perhaps more intriguing than the upper, in that the right one comes from behind, as if it could belong to another figure, and the meeting of the left one with the body is ambiguous. Whether Kali is modestly crossing her chest or playing with a nipple is also ambiguous, although the more visible hand is plainly active, its two rings echoing the dots of the nipples as well as the nostrils above. While the eyes are appropriately large, they hardly appear “pure and sad,” and if poor drafting prevents the shoulders from appearing “round like the rising autumn moon,” the breasts are drawn as semicircles, rather than “[pointed] like buds about to burst.” They are also high and small, and so more in accord with Western than with Hindu tradition. If to these discrepancies is added the fact that the hair is uncharacteristically curly, this Kali seems less based on an Indian model than on one that was closer to hand. Photographs of Grace Frick from this period show her as a curly-haired young woman who gazes at the camera forthrightly. In all of them her eyebrows are clearly marked and the nostrils are conspicuous.40

If indeed the sketches drawn for Grace in April of 1938 “display an unexpected erotic playfulness,” as Lonoff notes,41 then one might also propose that the two prominent rings on the ambiguously intertwined hands may recall the gold bands the two women purchased in Arezzo as a sign of their new love.

In Marguerite Yourcenar’s bedroom at Petite Plaisance, where books from the twentieth century reside, Gertrude Stein’s sparsely punctuated Paris France sits on a shelf next to T. S. Eliot’s Poems Written in Early Youth. In that slim volume, the expatriate American Stein comments on various aspects of her adopted homeland. Yourcenar, her French counterpart living in America, found one observation to be of special interest. She marked the second sentence in this passage from Stein with an X: “Everything is private and personal in France. . . . As my old servant Hélène once said, no Madame it is not a secret but one does not tell it.”42 Sometimes truths that can’t be told find an alternate mode of expression.