CHAPTER 8

Interlude

1939–1940

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.

—W. H. Auden

WHILE GRACE FRICK WAS BURNING the midnight oil in New Haven, Connecticut, Marguerite Yourcenar resumed her nomadic ways back in Europe. After a summer spent writing Le Coup de grâce, she left Italy on September 9, 1938, and headed to Sierre, one of her usual stopovers. Yourcenar’s fondness for that southeastern Swiss city was almost certainly occasioned by her love of the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, whose last home, Château de Muzot, a thirteenth-century stone farmhouse surrounded by beautiful orchards, was located there.1 She was still in Sierre in late September when the Munich Pact was signed, allowing the Third Reich to annex the strategic Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia.2

Yourcenar returned to Paris in October, where she had several literary irons in the fire. She was translating What Maisie Knew by Henry James into French; Le Coup de grâce was being considered for serial prepublication in the Revue de Paris; and she was trying to convince Gallimard to let her translate Frederic Prokosch’s Asiatics, which had been rejected by Stock. On December 10, 1938, Yourcenar was in Brussels to celebrate the election of the Paris-born Peruvian author Ventura Garcia Calderon to the Belgian Royal Academy of French Language and Literature.3 Returning to Paris after Calderon’s induction, she then crossed into Germany by train at Strasbourg on December 16 en route to the Austrian village of Kitzbühel.

By contrast with Paris, the irons that Yourcenar had in the fire at Kitzbühel had little to do with literature. One of the photographs she saved from that New Year’s holiday rendezvous shows her and the dark-haired Lucy Kyriakos standing side by side on a snowy ski slope. Looking at this picture, Josyane Savigneau has observed, “it is impossible to be mistaken about the relations between the two women. They are clearly a couple, in which, just as clearly, Marguerite is the dominant figure.”4 Michèle Sarde likens Lucy’s beauty to that of Jeanne de Vietinghoff; Lucy also shared with the object of Michel de Crayencour’s passionate affection the fact of being married to a homosexual.5 Seducing Lucy held all the mimetic attraction for Yourcenar of inhabiting the place her father had occupied with respect to his most ardently desired mistress; of possessing the woman who, in adolescence, had awakened her young mother Fernande’s capacity for passion at the Sisters of Sacred Heart convent in Brussels; of physically consummating a lifelong love that, while primarily like that of a daughter, also had a transgressively carnal component; and of being, for once, the amorous victor in the kind of love triangle that had dealt her such pain in the 1930s.6 Lucy was in André Embiricos’s wealthy circle of friends. Her husband, furthermore, was a cousin of Constantine Dimaras, the Athenian bookstore owner who translated Constantine Cavafy’s poems into French with Yourcenar.

Not much is known about Yourcenar’s relationship with Kyriakos, who was approximately two years younger than the author.7 The two women were friends before Yourcenar met Frick, however. This much we learn from a letter that Dimaras wrote to his cotranslator in November of 1937, by which time Marguerite was in New Haven with Grace. Dimaras had heard that the family of “the American young lady who is your friend” was involved in publishing and hoped to interest the LaRues in commissioning from him a manual of neo-Greek literature. About his and Yourcenar’s mutual acquaintances in Greece, Dimaras writes—a bit mysteriously—at the end of his letter, “There is nothing to tell you about Athens. I have mentioned Calamaris to you twice, and I plan to get your address from André Embiricos.8 So, you see, everything takes its course, Lucy is vanishing beneath a sky too fair for her. I think that by coming back to settle in Athens, you will be sure to find at least some real friends.”9 Whether Yourcenar had mentioned the possibility of settling in Athens one day or Dimaras, as in the rest of his letter, was trying to convince her to do so, we can only guess. But what Dimaras says about Lucy Kyriakos may refer to the young woman’s overindulgence in alcohol.10

One thing we do know about Lucy is that she was not, like most of Yourcenar’s acquaintances, an artist or a writer.11 Lucy also had a young son, though though it is probably safe to assume that he was not a major focus of his mother’s ski vacation in Kitzbühel.

In July of 1983 Mme Yourcenar showed me her personal photograph albums, providing brief descriptions of the important people in them. As I wrote in my journal at the time, when we reached the photograph of “M.Y. in slacks smoking a cigarette with the three dark-haired Greek women with whom she shared for four months the house of ‘un ami’ in Greece,” she leaned over to single out Lucy, saying, “She’s the one who was my friend.”12 Asked how they got along, she replied, “Oh, very well,” laughing heartily.

Because Kyriakos was an excellent skier, which Yourcenar was not, it was more than likely she who invited her French friend to spend the winter holidays vacationing in Kitzbühel.13 They may both have stayed with a certain Baron Gutsmansthal in that Tyrolean village. As Yourcenar wrote to “Nel” Boudot-Lamotte on January 6, 1939, “In the event that the proofs of Coup de grâce are ready before 1 February, could you have them sent to me?” She would be staying, “until 18 January, c/o Baronin Gutsmansthal in Kitzbühl; afterward, and until 30 January, at a Viennese boardinghouse.”14

Contrary to this expressed intention, and to her own memory of staying in Austria until March, Yourcenar left Vienna on January 26.15 Two days earlier she had gone to the Consulate General of Greece and obtained a visa for a one-year stay in that country. From Vienna’s Hungarian Consulate on the same day, she received permission to pass once through Hungary until March 24. On January 25 Yugoslavia’s General Consulate stamped her passport with a visa for transit through that kingdom, valid for one month. She left Vienna by train the next day and crossed the border into Hungary. January 27 found her traversing Yugoslavia and entering Greece at Idomeni. This was the beginning of the four-month stay that she mentioned to me in 1983.

One of the photographs from this period shows Lucy Kyriakos posing on the rocks at the edge of the sea, wrapped only in a towel.16 Yourcenar spoke of this holiday in a letter to Boudot-Lamotte:

I spent Easter week on Eubeoa, far from any road and more than half an hour’s boat ride to the nearest village. The worries of the world arrived there muffled, but they arrived nonetheless. The landscape was so beautiful there is nothing one can say about it: sunbathing on the rocks in perfect solitude, the sound of a magical little bell in haunted woods, Easter’s roast lambs, midnight mass on Holy Saturday in a mountain monastery among drunken monks, dirty and solemn, reciting prayers like incantations.17

Several other photographs were taken on the property of Athanase Christomanos, also on Euboea, where Yourcenar was staying with Lucy, Lucy’s cousin Nelly Liambey, and Lucy’s sister Kharis. One of them shows Marguerite, smoking a cigarette, arm in arm with Lucy in Christomanos’s courtyard.

As correspondence from that era now confirms, Yourcenar spent much of those four months in Athens, where she was translating with Constantine Dimaras.18 On May 18, 1939, after what was probably the longest stretch of time she ever spent in Greece, Yourcenar left Piraeus on a freighter, headed for France.19 Five days later her passport was stamped for a transit stop at Genoa, Italy, and on May 25, she went ashore at Marseilles.

There is little doubt that Kyriakos was one of Yourcenar’s feminine conquests. Though she and Frick had forged an amorous liaison that stayed very much alive in the letters they wrote to each other, it is not entirely surprising that Yourcenar would revert to her womanizing ways once she was back in Europe on her own. She had never been involved in a long-term relationship with another woman, and her father had certainly not been a model of fidelity. She may even have been troubled by Lucy’s drinking problem, which could have become more pronounced—or more obvious—over the course of Yourcenar’s long stay in Greece. It was still a painful memory more than forty years later when she spoke of it in regard to the alcoholism of another friend. Kyriakos was the only other person in her life who had struggled with that particular affliction.20

Contrary to much that has been written about this period, some of it by Yourcenar herself, a return to the United States was already in the works before she even left Greece. It was not a last-ditch plan that cropped up in August of 1939, as the political situation in Europe grew ever more ominous. As Yourcenar states in an unfinished “Self-Commentary”: “In Greece, I was working on a translation of Constantine Cavafy; I had booked passage on the Nieuw Amsterdam, whose maiden voyage was to take place in September, planning to spend several months visiting an American friend.”21 By early June 1939 she was in Belgium, almost certainly for reasons related to her American voyage: in the passenger manifest of the ship on which she eventually sailed—the SS Manhattan, and not, as has been reported, the SS California—she is identified, for the first and only time in her life, as being Belgian.22 In fact, Yourcenar’s listing for this crossing displays several anomalies. Her first name is listed as “Margarete”; in the “Married or Single” column next to her name appears the letter D, for “divorced”; her nationality is listed as “Belguin,” her birthplace as “Belgum,” and the city of her birth as “Brussel”!

From Brussels she returned to France on June 11 via Flines-les-Mortagnes en route to Paris and the Hôtel Wagram.23 By July 19 she had already been to the American Consulate in Geneva trying to procure her U.S. visa, as she had done in 1937. This time, however, since she had no fixed address, and since international travel was now more closely monitored, someone would have to attest to her habitual residence in Paris. She told Boudot-Lamotte at Gallimard that the United States wanted “to be sure it could get rid of me at the end of one year.”24 She needed Gallimard to say—as quickly as possible—that she was working on translations of American authors and would have to return to France in that connection in 1940. On August 16, 1939, she was “seen for the journey to the United States” by Heyward G. Hill at the American Consulate in Geneva. Her visa was issued that same day.

On September 3 Great Britain and France declared war on Germany, throwing Yourcenar’s plans into disarray. When she got back to Paris later that month, she learned that the Nieuw Amsterdam would not sail after all, and ships to the United States were scarce. She thought briefly of returning to Greece as an envoy of the French Ministry of Information, but no appropriate opening was available for her to fill.25 About her short stay in Paris during the uneasy weeks of the Phony War, Yourcenar remembered a conversation at the Hôtel Ritz bar with Jean Cocteau, who was “as always more concerned with charming and bedazzling than with the things that were happening, which had not yet affected him.” Another acquaintance, the French singer Marianne Oswald, dreamed of “starting up a nightclub in New York, exclusively for women.” The surrealist writer Julien Gracq was “glimpsed in an English friend’s salon, . . . where I heard a woman sing a song one evening in Gaelic whose name I don’t remember but whose rhythm later found its way into La Petite Sirène.”26

Yourcenar had crossed into France from Switzerland on September 28. Six days later, having heard that a ship would be sailing to New York from Bordeaux, she obtained a time-limited visa to leave France from that port for the United States from the Passport Office of the Paris Préfecture de Police. On October 15, 1939, she finally was able to sail.

The contrast at this juncture between Marguerite Yourcenar’s experiences in Europe and Grace Frick’s back in New Haven could hardly be sharper. By July of 1939, having received yet another extension, Grace had made what she considered to be respectable progress on her dissertation.27 While Yourcenar was desperately trying to find a way out of France, Frick was pursuing a variety of pleasurable hobbies: hiking, music, reading, and theater.28 She had just been hired to teach English composition at Barnard College for the 1939–40 academic year. After spending August and most of September with her family in Kansas City, Frick moved into a faculty apartment owned by Columbia University at 448 Riverside Drive in Upper Manhattan. Yourcenar would join her there on October 22, 1939. The crossing from Bordeaux to New York was extremely nerve-racking because the ship had to make several detours to avoid German submarines.29 She arrived in New York just in time for a pro-Nazi parade organized in Manhattan by the German-American Bund;30 for someone fleeing Hitler’s aggression in Europe, it was not a welcome spectacle.

At Barnard Grace was working yet again, as she had at Wellesley and Stephens, for an ardent promoter of women’s education. Virginia Gildersleeve taught English and was dean of Barnard College for more than thirty years.31 Coincidentally, she had been one of the speakers at the celebration that took place the year Frick graduated from Wellesley College.32

While Grace fulfilled her duties at Barnard, Yourcenar tried her hand at commercial translation and worked with some of Frick’s Yale friends to plan a Midwestern lecture tour.33 Paris fell to the Germans in June of 1940, and the world that Yourcenar knew seemed to be coming to an end. But as the French scholar Mireille Blanchet-Douspis has observed, another world was opening its doors. Blanchet-Douspis describes how expansive Marguerite Yourcenar’s experiences in America would be:

Through her contact with the intellectual milieus that Grace Frick opened up to her, she was introduced to problems to which her personal sensitivities rendered her receptive but which French culture had not yet begun to address: ecology and minority rights; and she began to familiarize herself with cultures that, viewed from Europe and submitted to the decadent judgment expressed in “European Diagnosis,” did not appear worthy of the same consideration as European civilization. The intellectual universe of Marguerite Yourcenar was enriched by unknown, perhaps even unimagined novelties; she acquired maturity and a broader, certainly keener comprehension of living beings considered as a whole. What could be described as “more modern” aspects insinuated themselves into her makeup, but without separating her from her native language and culture.34

Yourcenar’s interest in American blacks was piqued, as we have seen, during her trip down south in the spring of 1938. The apartment that she and Frick shared on Riverside Drive was not far from Harlem, Manhattan’s noted African American neighborhood. In the 1920s and 1930s that quarter was home to the explosion of music and art known as the Harlem Renaissance. The aging Yourcenar spoke often of her early contact with certain members of Harlem’s black community. As she told Matthieu Galey, she and Frick had met “Father Divine, a sort of prophet, who was well known at the time,” during the year they spent living in New York:

My American friend and I sometimes ventured up to Harlem to hear him. Or rather to watch him, because he didn’t talk, he ate. He used to sit at a very large table, but the meal he ate was quite modest, consisting of chicken necks and feet, potatoes, and various other low-cost items, served by magnificent black women dressed in white synthetic satin. Each dish was set before Father Divine, who stared at the food with a vacant look while continuing to eat. The people, the blacks, who were there, quite a large crowd, pressed up against the table and said, “Bless us, Father, touch us, Father.” It was quite moving. I made use of this scene in my attempt to portray the prophets’ banquet at Münster in The Abyss. I tried to capture the almost sensual enthusiasm of the crowd at Father Divine’s dinners.

When we returned home to our tiny apartment on Riverside Drive, which was not then the dangerous neighborhood that people tell me it has since become, the [black] doorman came up to us with a worried look and said, “What! You mean to say you went to Father Divine’s? That wasn’t very smart, he’s probably cast a spell over you.”35

The black doorkeepers at 448 Riverside Drive were indeed leery of “sorcerers” like Father Divine, but they loved gospel music and the blues. And they weren’t above breaking the rules to “covertly let street singers into the courtyard of the building.”36 As Marguerite would later write,

One of them, whose tenor voice could almost reach the highest notes of a soprano, had become friendly with Grace Frick. . . . We would invite him to have supper with us.

One evening she said, “Jim, the range of your voice goes up very high.”

“High?” he exclaimed. “I’ll say. All the way up to the third floor!”37

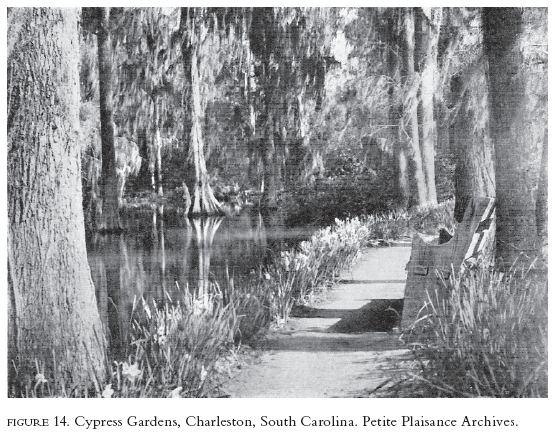

As soon as they were able, Frick and Yourcenar were traveling south again. Barnard’s winter vacation in December 1939–January 1940 found them back in Charlottesville, Virginia. Over spring break they returned to South Carolina.38 A postcard from the latter trip, preserved in one of Yourcenar’s personal photograph albums, suggests the kind of pleasure the two of them took in their visits to the South. It is an artistic image from Charleston’s Cypress Gardens in which lush subtropical foliage fills the scene.

Prominent in the foreground is a weathered wooden bench overlooking still water beside a walking path. On the back of the card, Yourcenar transcribed in French two verses from the seventeenth-century poem “The Two Lovers’ Promenade”:

These waves, tired of moving

Across this gravel,

Are reposing in this pond

Where long ago Narcissus died.

The shadows of this crimson flower

And of those bending reeds

Seem in the depths to be

The dreams of the sleeping water.39

On Easter Day 1940 Yourcenar wrote another postcard—in English—to Lucy Kyriakos. It bore Elizabeth O’Neill Verner’s well-known drawing of Charleston’s Marshall Gate. The spelling, punctuation, and other style elements are all her own:

Dearest Lucy — Do you remember St. Georges? (my greetings to all) Only a year ago — I am for a few days in this lovely little town, in the middle of magnolias gardens. I had your letter and will answer — but I worked hard and had no time yet. When will we see each other again? Times are bad — But life all the same has pretty moments.

Love from Marguerite40

In one of those temporal disjunctions so typical of Yourcenar, the postcard bears a notation appended to it by the author stating, almost as if this were a reason for not mailing it: “Never sent. She died during the bombardment of Ioannina during Easter week in 1941.”

The only mention of Lucy—or rather of “L.K.”—in the Pléiade chronology appears in a description of two poems that Yourcenar wrote during the first six months of 1942.41 “Greek Flag” recounts in seven quatrains the true story of a Greek evzone who, charged with removing the national flag flying over the Acropolis when enemy troops entered Athens, wrapped himself in the banner and leapt to his death. The poem about Lucy, “Epitaph, Wartime,” is a short but loving rhyme that eerily echoes Constantine Dimaras’s 1937 comment about her disappearing beneath a sky too fair for her:

The iron sky crashed down onto

That tender statue.42

When speaking of Lucy in the 1980s, Marguerite Yourcenar said that at the end of her life, the Greek woman plunged deeper and deeper into alcoholism, drifting from bar to bar.43 Our only hope of learning more about what really happened between the two of them may reside in the sealed file at Houghton Library—but it’s a long way to 2037. What Grace thought of all of this we may never know.

It is hard to imagine that the Fricks and LaRues of Kansas City ever got wind of Yourcenar’s European affairs. They did not think much of Grace taking up with an exiled Frenchwoman about whom they knew almost nothing, however. Yourcenar told one friend, Deirdre “Dee Dee” Wilson, that she had never been welcome to visit Kansas City with Grace.44 To another she stated that the family had tried to separate the two of them—and almost succeeded—by hiring a lawyer to deprive Grace of her inheritance.45 Yet another friend once wrote that Grace’s “Kansas City family did not approve of her teaming up with MY, feeling that she was only wanting to be financially supported while she pursued her career.”46

Much has been made of Yourcenar’s poverty upon arriving in the United States, but she was not penniless. Grace in fact asked her brother Gage if he would be willing to oversee Marguerite’s investments. He declined. The Fricks and the LaRues, conservative Midwesterners, simply did not want Grace to partner up with a woman. Nor, in their eyes, was there any good reason for her to hitch her wagon to a dim French star.