CHAPTER 11

Extracurricular Activities

1942

Cool waters tumble, singing as they go

Through appled boughs. Softly the leaves are dancing.

Down streams a slumber on the drowsy flow,

My soul entrancing.

—Sappho

THERE WAS MORE TO LIFE than work. It did not take long for Grace Frick and Marguerite Yourcenar to discover a cultural institution that would play a major role in their life during the Hartford years, the Wadsworth Atheneum. Its director, the dynamic and innovative art impresario A. Everett Austin Jr., became an immediate friend.1 Known as Chick, Austin was Harvard educated, fluent in four languages, and comfortable with his bisexuality in an era of strict conformity. He loved European art. How could Grace and Marguerite not have befriended him?

The Atheneum had chosen the then twenty-six-year-old Austin as director in 1927. He had an eye for rising artists and made many purchases for the museum’s collection that became the envy of much larger and better-endowed institutions: a Mondrian in 1935, Salvador Dalí’s Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach in 1939, and Max Ernst’s Europe after the Rain in 1942, to name a few. At the oldest public art museum in the United States, Austin was responsible for many American “firsts”: the first Picasso retrospective, the first opera with an all-black cast, the first Balanchine ballet—all of them in the single year 1934. He was also a magician, a classical dancer, and an amateur actor.

But his talents were not always cherished by the Wadsworth’s conservative trustees. In their eyes Austin took too many risks and spent money altogether too lavishly. In a 1982 interview, Yourcenar remembered her friend: “There is a line of Shakespeare. It’s Cleopatra who says it in Shakespeare: ‘I am air and fire.’ Well, Chick Austin was air and fire. [He had] great enthusiasm, a great facility to respond to the moment, the excitation of the moment. . . . He was of course a prince.”2

Yourcenar’s biographers have had little good to say about Hartford. Josyane Savigneau calls it “a rather uninteresting city”; Michèle Goslar, “a city plagued by laborers and rats.”3 Yourcenar herself once described it as “reactionary, chauvinist, and Protestant.”4 But Chick Austin was a one-man cultural revolution. In 1935, no less a figure than the French architect Le Corbusier enthused that Austin and his museum had turned the small provincial capital of Connecticut into “a spiritual center of America, a place where the lamp of the spirit burns.”5

In 1942 Grace and Marguerite got involved in an exciting creative venture there. Chick Austin was inspired that spring to bring prominent European artists in exile to Hartford for a special show.6 Painters in Attendance, so dubbed in the hope that the artists themselves would appear at the opening, would last only a week, May 22–29. It would feature the work of such luminaries as André Breton, Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, and Joan Miró. Coinciding with the first two days of this exhibit, Austin conceived a program of theater, music, and ballet called The Elements of Magic. Each of its parts would evoke one of the four elements: earth, water, fire, and air. For water, Yourcenar wrote a “free transcription” of a tale by Hans Christian Andersen that had been “the delight of [her] childhood.”7 Grace Frick translated the play into English under the title The Young Siren.8 This was the first work of the imagination that Yourcenar had penned since her arrival in the United States, and she told her friend Jacques Kayaloff what a pleasure it was to be writing again.9

A few days before The Elements of Magic was to open, the Hartford Times published an article about Yourcenar’s play that included an interview with the author. “I read the story long ago,” Yourcenar explains,

in one of those little books they used to sell at the stations in Paris. It has always fascinated me, and I’ve thought often that I’d like to do something with it.

I don’t know where the Danish writer got it. It may be an old folk story, but it can be treated as popular mythology, like the Greek tales or the Scandinavian. So I have taken the basic elements, and used them in my own way.

The original fairy tale is extremely sweet, seen through 19th century Romanticism, but I have approached it from a more modern point of view.

Judging from the comments she made to the Hartford Times reporter, Yourcenar was pleased with all aspects of Chick Austin’s production:

I am very grateful to Mr. Austin for the opportunity to write this little play. It is hard to write novels now. We are too near things, in the middle of the turmoil. But I am happy still to write poetry.

I am also delighted with the way Truda Kaschmann has created and directed the gestures for “The Young Siren.” In the first scene the mermaid speaks, but in the second and third, you see when she has lost her voice she must express herself through another medium, and I feel that the motions Mrs. Kaschmann has devised are extraordinarily beautiful and well suited to the meaning.

I have lived in the islands of Greece, but I have never met a real mermaid. However, I am sure this is what she would be like.10

Truda Kaschmann, who taught modern dance at Hartford Junior College, remained a friend of Grace and Marguerite’s for life. She also created and performed in an expressionistic ballet for the element fire, inspiring Yourcenar to describe her years later as “a dancer from Berlin who left Germany in time to escape the fires of the crematoria.”11

After Frick’s death, Truda Kaschmann made a contribution to what had by then become the Hartford College for Women in memory of her friend. In thanking her, Yourcenar wrote, “All good wishes after our long silence, and all my thanks to have made a contribution to The Library Fund for Hartford College for Women in memory of Grace Frick. I still remember you so well in that décor, working with Grace.”12

Chick Austin, for his part, would soon find himself ousted as director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, and Yourcenar considered herself at least partly responsible for his demise.13 Austin was a forward-thinking member of the artistic avant-garde. Hartford, for the most part, was anything but. The Atheneum’s trustees constantly tried to rein Austin in, particularly with regard to his theatrical ventures, each one in their eyes more outrageous than the last. In 1943 Yourcenar suggested that he mount the Jacobean tragedy ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore. She even lent him her copy of the text, helped him compose the script, and worked with him on staging.14

Like Yourcenar’s 1934 short story “D’après Greco,” John Ford’s 1633 play concerns an incestuous brother and sister who defy the societal forces aligned against them, a fact that Ford fails to condemn. The audience for the premiere was stacked with friends of Chick’s who came up from New York City to show their support for his daring venture. They spent the night camping out in a lounge at the Atheneum, where Marguerite and Grace joined them in a lively postperformance discussion of the symbolism and merits of incest.15 But for the Hartford theatergoing public, any favorable treatment of this topic was beyond the pale. As Eugene Gaddis notes in Magician of the Modern, “more letters were addressed to the editors of the local press [about this play] than for any other program or exhibition Chick undertook, continuing for days after the production closed. They fairly shrieked about what they considered a diseased excuse for a play. Some saw it as an attack on the Roman Catholic Church and thus a slap in the face of the Irish and Italian communities in Hartford.”16 The Atheneum’s trustees were not amused. Chick was urged to take a one-year sabbatical from his post. When that year was over, with Austin showing no signs of toeing a conservative line, he was quietly let go.

Incest was a topic that held special interest for Yourcenar. Her novella Anna, Soror . . . tells the story of forbidden passion, fought but eventually consummated, between a brother and sister in late-sixteenth-century Naples. Indeed, Yourcenar’s depiction of Anna’s incestuous coupling with her brother Miguel recalls the scene in Ford’s play: it occurs, between two young people imbued with Christian piety, on Good Friday.

Three months before the premiere of Austin’s Elements of Magic another theatrical event occurred in Hartford that, though relatively minor in its own right, would have the notable result of inspiring Yourcenar’s next creative effort. On Valentine’s Day 1942, Dean Frick hosted a meeting of the Hartford Wellesley Club at Hartford Junior College. As the Hartford Times reported, Frick would be speaking to the group about the various activities of her students. She would then introduce Truda Kaschmann’s dance class in a performance, accompanied by the college choral group, of an abridged version of Euripides’s Alcestis.17 Frick’s undergraduate sorority had staged the same play in May of 1923.18 Just as Yourcenar worked closely with Kaschmann on The Elements of Magic, she took an active part in this production, too. She not only adapted and translated Euripides for the Hartford girls’ choral performance, she directed it as well. She did not, however, attend the performance. Instead she spent that day at Hunter College in New York City at the organizational meeting of the Groupe des Hautes Études Françaises, described by the Hartford Courant as “a division of the New York School for Social Research and a part of its program for the University in Exile.”19 Yourcenar obviously took her responsibilities as an educator, and a French intellectual, seriously. Her formal ties to France were not immutable, however. It was also in February of 1942 that Yourcenar first filed her application for American citizenship.20

Having sustained a breakneck pace at Hartford Junior College for two years without respite, Grace Frick must have been ready to drop. Board chairman Howell Cheney and even the college housekeeper were urging her to take some time off.21 But when she finally agreed to take a short vacation in the summer of 1942, she found it hard to tear herself away. While she and Marguerite were on their way to Maine for two weeks with Paul and Gladys Minear, Grace insisted on stopping en route to check out Hartford’s competition in the form of Westbrook Junior College.22

The Minears had discovered the splendors of Mount Desert Island several years earlier, staying in Seal Harbor as guests of a colleague from the Yale Divinity School.23 They returned to that small village in the summer of 1942, renting an apartment above the general store. It was to that apartment, fatefully, that they invited Grace and Marguerite.

Seal Harbor is one of several villages that make up the Town of Mount Desert. It is located on the southern tip of the island’s easterly landmass between Northeast Harbor to the west and Otter Creek to the east. John D. Rockefeller’s ninety-one-room “cottage,” The Eyrie, was nestled in the woods there in the 1940s—it has since been torn down—and many other wealthy families had been drawn to the area by its rugged beauty and many outdoor recreational opportunities. Not only was Seal Harbor a prime destination for sailing adventures, it was also on the edge of Acadia National Park, where one could hike through the wilderness, horseback ride on Mr. Rockefeller’s carriage trails, and swim, boat, or fish in several freshwater ponds and lakes. For Grace and Marguerite it was “an epiphany.”24

Much has been written about the coup de foudre that discovering modern-day Greece was for Yourcenar in the early 1930s. A decade later, on another continent forty-five hundred miles away, a similarly life-changing event lay waiting for her, appropriately enough, on an island named by the French explorer Samuel de Champlain in 1604. Paul and Gladys Minear have testified to what a revelation Mount Desert Island was for both Yourcenar and Frick, neither of whom knew that such a place existed in America when they first went there in 1942. That the Minears used the word “epiphany” to describe the couple’s reaction to this wild new place suggests how profound their immediate feeling for it was. Grace was already an ardent horsewoman, and Acadia’s carriage roads drew her like a magnet; she would spend entire days in the saddle. Marguerite had long been a lover of islands, which, as she would often say, are both a kind of universe in miniature and an outpost at the edge of an unknowable beyond.25 This island in particular, with its smattering of small villages, its dark forests of fir, and its low, rounded mountains, can hardly have failed to awaken in the Frenchwoman joyful memories of childhood summers spent in the similar landscape of Mont-Noir in northern France.

In July of 1973 Yourcenar would pen a nostalgic remembrance of her summer stays at Seal Harbor in a personal journal. She and Frick, both by that time seventy years old, had taken their Kansas City visitor Ruth Hall to the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden high on a hill in the village of that family’s former vacation home. Yourcenar had climbed a slight slope to a spot where one could see a Chinese bodhisattva statue and from which one could view a small lake in the distance below, “with its fringe of reeds and green foam. This was the lake,” she goes on to say,

where I often went swimming during my first stays here, over two or three blazing summers; I have often gone around it on foot and once or twice, unforgettably, on horseback on a beautiful autumn day with a chill already in the air; and I remember the exact spot where, beneath a cluster of trees, I came across a fox, the spirit of that solitude. One of the most profoundly lived parts of my life is here.26

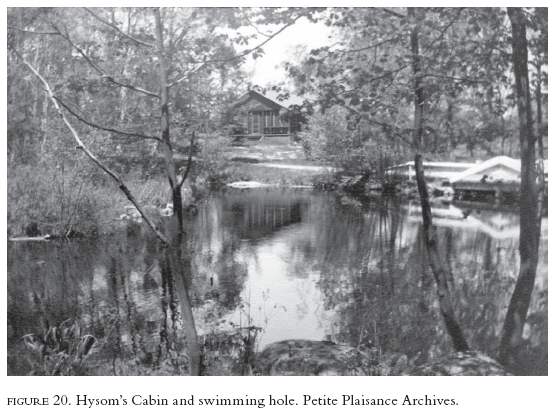

The two were so entranced by the island that at the end of their stay with the Minears, they set about finding a rental for themselves in another location. They chose one in the picturesque village of Somesville, the oldest permanent settlement on Mount Desert Island. Tucked away from the main road was a little log house known as Hysom’s Cabin overlooking Somes Brook and located just outside the gates of a scenic old cemetery. Inside the bungalow hung a framed copy of a poem written by a previous renter, Walter C. Guthrie, entitled “The Brook (at Hysom’s Cabin).” The poem—which more than seven decades later still hung where the couple first found it—suggests what appealed to Grace and Marguerite about the cabin’s secluded brookside location:

Far from the city’s hectic throng

I listen to your endless song,

Alone with you at early morn,

What myriad thoughts in me are born!

Rushing, eager, on your way

From the tarn where naiads play,

Caressing rocks with cooling quaff

While at would-be barriers laugh,

As I watch you wend your way,

Chanting ceaseless, vibrant lay,

Is your path from Whiting’s deep

But a memory that I keep?

Or does your onward, labored course

To the Sound from natal source

Tell me, — since the world began, —

This is life to every man?27

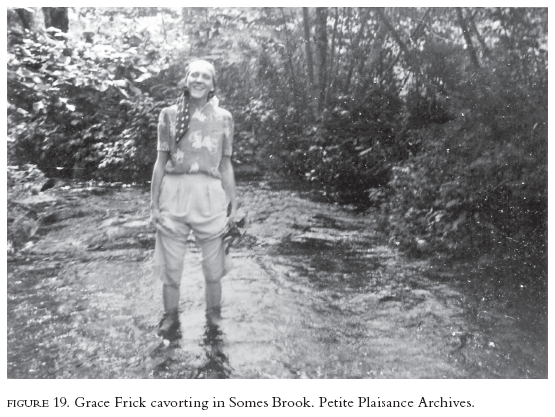

Guthrie’s naiads would almost certainly have called to mind for Marguerite and Grace the amorous nymphs of Yourcenar’s Greek stories “The Man Who Loved the Nereids” and “Our-Lady-of-the-Swallows” from the 1938 collection Oriental Tales. Not only did Somes Brook wend its way from the naiads’ playground to the sea, it also paused en route to form a basin deep and wide enough to swim in just a few yards from Hysom’s Cabin. The vacationers wasted no time diving in, and one near neighbor, Elaine Higgins Reddish, later remembered their habit of skinny-dipping there on a hot summer’s night.28

Grace and Marguerite liked this rustic cottage so much that they immediately reserved it for the following summer. Eventually they would try to buy both the cabin and the surrounding land. In the process of researching that possibility, they discovered that the rights to the brook were owned by four feuding families. As Grace told Donald Harris and his wife in 1977, “we ran into a terrible tangle with the deeds. We spent much of a hot summer in a courthouse in Ellsworth, and so we know much more about the families of these people than they do.” This conversation took place near Somes Brook, where Yourcenar was being filmed by a French television crew. When Harris and his wife returned to the car where Frick had remained to keep warm on that November day, they reported that Yourcenar had mentioned their attempt to purchase Hysom’s Cabin, adding that she had cleaned out the “torrent” with her own hands. Whereupon Frick replied: “Yes, we . . . She says I but . . .” When the three of them stopped laughing, Grace added, “Comes naturally in French, she tells me.”29 In the end, the two of them gave up on buying the little log house primarily because the plot of land on which it stood was so small.

While providing both Grace and Marguerite with much-needed rest and recreation, this first visit to Mount Desert Island in 1942 also afforded Yourcenar the leisure to write Le Mystère d’Alceste, an offshoot of the work she had done a few months earlier with Grace Frick’s students for Truda Kaschmann’s modern dance production. In fact, Yourcenar hints at the Kaschmann connection in her introduction to the published version of the play when she calls one particular sequence a “tragi-comic ballet.”30

Euripides’s Alcestis is based on the mythical character who selflessly offers up her life in exchange for that of her husband, Admetus. Yourcenar turns this myth of wifely devotion and voluntary sacrifice on its head. In her version of the story, Alcestis repudiates the poet-husband from whose world she has largely been excluded, seeing death as a means of escape. When brawny Hercules comes along to save her, so different from the writerly, starry-eyed Admetus, it is not so much his legendary strength that brings Alcestis back to life as it is her desire for him. Hercules embodies elemental forces. He likes to eat and drink, and he indulges with gusto in all the pleasures of the flesh. Yourcenar’s Alcestis returns to the world of the living in the hope of exchanging her irresolute husband for the powerful, sensual Hercules.

Yourcenar would one day see herself reflected in her voiceless young siren of 1942. A similar parallel exists between her and the character Alcestis. Yourcenar’s evolution as a writer and a person in many ways so different from who she had been before the war was mediated to a significant degree by her relationship to the natural world of Mount Desert Island. As she said years later, it was because of her own contact with elemental forces that the focus of her thought slowly shifted “from archeology to geology, from a meditation on man to a meditation on the earth.”31 The predictable unfolding of Yourcenar’s career as a writer had come to an abrupt halt when World War II began. In America, where her physical safety was assured but her literary lifeline was largely cut off, she underwent over the course of several years a profound philosophical metamorphosis. Like her character Alcestis, Yourcenar experienced a process akin to that of dying and being reborn. In Le Mystère d’Alceste, ironically, the female figure of Death describes herself to Hercules not as a killer but as “a midwife veiled in black” who gives birth to souls.32 Though transformation did not occur over the course of one summer, Mount Desert Island was the midwife of Yourcenar’s rebirth.