CHAPTER 15

The Life Their Wishes Never Led

1945

A child is a hostage. Life has you.

—Marguerite Yourcenar

THERE WAS MORE TO GRACE Frick and Marguerite Yourcenar’s eagerness to find a house on Mount Desert Island than meets the eye. And certainly more than the popular intimation to the effect that buying a house in the United States was a ploy on Frick’s part to prevent her partner from moving back to Europe after the war. Yourcenar had initiated the long process of obtaining U.S. citizenship in early 1942. When she was naturalized on December 12, 1947, she relinquished her French nationality.1 Yourcenar had roots in America now, and they were growing deeper. For the future she and Frick had in mind, the couple wanted a home of their own. Though they loved Hysom’s Cabin, as soon as they knew they couldn’t buy it, they started looking elsewhere.2 West Hartford was convenient for now, with Frick teaching in New London and Yourcenar commuting to Bronxville, but Maine was their spiritual home.

In the mid- to late 1940s, they tried to wrest a cottage on the Shore Path in Bar Harbor from a stubborn realtor. Frick later wrote to the legendary Natalie Clifford Barney in Paris about the experience. Barney’s wealthy family had owned a spectacular mansion, Ban-y-Bryn, overlooking the water in Bar Harbor, where young Natalie had spent her early summers swimming and riding and traipsing nymph-like through the woods with her friend Eva Palmer.3 “The site is beautiful,” Frick wrote, “and we tried for five years steadily to get hold of the small white cottage of the McClean gardener.” But there were a dozen “outhouses” on the property, including a monkey cage and a bowling alley, and the realtor was determined to sell everything at once. The couple finally gave up on the place only to see it sold a year later to a local man “who ruined the tract by converting the doll’s house into a Ladies Home Journal bungalow, and building a duplicate model on the tennis court, where we had hoped to have a garden!”4

A major impetus for their house hunting, much of it done by Frick on horseback, was the couple’s desire to adopt a child together.5 Grace had always had a soft spot for children and young people. During her and Marguerite’s first full summer in Somesville she inaugurated the custom of mounting plays with local children, in which she would engage off and on throughout her life, often with help from her companion. That first production, based on the biblical story of Moses in the bulrushes and staged alongside Somes Brook, is documented by a series of numbered photographs preserved at Petite Plaisance. The late Elaine Higgins Reddish of Somesville took part in this performance. In a 2002 interview she remembered Baby Moses, a child’s doll, being floated down Somes Brook just across from Hysom Cottage in a basket.6 As Jerry Wilson later wrote, having heard about the play from Yourcenar, “One boy reported that the order had been given in the ‘Post Office’ to kill all Jewish babies and when they got all of their towels cum costumes back, Mme Y got morphions [sic] and had to have her head shaved to treat them—telltale signs of village cleanliness.”7 Fortunately, short hair was her style and it was hot.

Five years later Yourcenar was willing to take her chances again when she helped Frick stage another production of the same play on the beach in Seal Harbor, where they were staying that summer.8 The two of them would still be mounting plays with children, and taking part in them, thirty years later, when Frick, in the year before her death, played the spirit of a tree in the yard behind their home. This particular performance was adapted from a Japanese legend in which a handsome young man falls in love with and marries a beautiful girl he encounters in the forest. She turns out to be the spirit of a willow tree, and when the tree is felled, she falls to earth and dies.9 Because there was no willow in their garden, Frick and Yourcenar pressed one of their favorite tree species into service for the occasion, a white birch.

The couple may have been inspired to think about adopting because so many European children had been orphaned by the war. Grace Frick knew from personal experience what an important role an adoptive family could play in the life of a child. And she consigned to the title page of the 1946 daybook the telephone number of New York’s Child Adoption Committee.10 But Yourcenar may have made the first contact related to the adoption project when she had “luncheon” in Bronxville with Mme Andrée Royon on February 10 and 24, 1944. Royon, a forty-eight-year-old child psychologist, was both a delegate of the Save the Children International Union based in Geneva, Switzerland, and on the staff of New York’s Save the Children Federation.11 She was also a French-speaking native of Ghent, Belgium, with a recent PhD in psychology from the University of Geneva, where Marguerite Yourcenar once studied.12 Like Yourcenar, she had become a part-time instructor at Sarah Lawrence College in the fall of 1942.

On May 10, 1944, Frick and Yourcenar met Royon for lunch together in New York City, inviting her to visit them that summer in Maine.13 She ended up coming to Somesville for nine days in mid-August, during the second half of Alice Parker’s three-week stay. Although one can’t be entirely sure what happened, the 1944 daybook bears strong suggestions that Mme Royon succumbed to Yourcenar’s renowned powers of seduction during that island holiday.

Parker’s visit ended on August 17, and Royon left the next day for New York. A telegram soon arrived from Royon. It was followed on August 29 by “conflicting letters” from Royon and Parker. Two days later, Frick noted in the daybook, “M.Y. writes Royon firmly.”14

Not firmly enough it seems, however. On September 26, with Yourcenar unwell and trying to rest at Jacques and Anya Kayaloff’s apartment in Manhattan, “Royon showers yellow roses on M.Y., and flees.” Frick and Royon met at Schraft’s three days later “for the last time.” According to the daybooks, neither she nor Yourcenar ever saw Mme Royon again.15

Nineteen forty-five began for Frick and Yourcenar with an unusual winter trip. On January 5 the couple made a nearly seventeen-hour journey by rail and by bus to the seaside village of Camden, Maine. Florence Codman had a place on Bay View Street there called Stone Chimney, where she and her companion, Margot Hill, had spent the holidays that year. It was 1:00 a.m. when the travelers finally arrived. The next day Frick went walking in the village and climbed partway up Mount Battie. The daybook for January 7 records a spirited difference of opinion between its two contributors. Yourcenar writes, “Glass below zero outside fisherman’s hut. Grace has a long walk from Camden to Rockport and back and comes back nearly frozen.”

“No!” counters Frick. “Lovely walk, beautiful houses, woods in snow, little boy. Not frozen at all!!”16

On January 8, another frigid day, the two women went back to Portland, where they caught separate trains. Yourcenar headed to Bronxville for a meeting, while Frick began a two-day marathon. Over the course of forty-eight hours, she cleaned out the unheated Hysom’s Cabin, spent twenty-four hours with Mary Marshall in Waterville, visited with the Minears in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, and called on Laura Lockwood at Wellesley—traveling from one place to another by train, bus, taxi, and on foot. Yourcenar was manning the daybook that evening: “Marguerite comes back from Sarah Lawrence. Grace meets her at station. Good time in front of the fire.”17 Even after only brief separations, reunions were sweet. When Grace went away for longer periods, usually to travel with Aunt Dolly or Aunt George, Marguerite often made notes in the daybook such as “Joy: Grace phones,” filling up the page with her drawing of a sunrise on the days Grace would come home. These were the years when Grace started calling her companion Greta, Grete, or Gretie.

We have noted the strengthening of Frick and Yourcenar’s couple that occurred when the women changed their wills in 1943. In November of 1946 Yourcenar took a step further when she added a codicil to her will making Frick both her literary executor and the sole beneficiary of her literary estate. This was an expression of confidence in her American companion’s professional judgment whose importance cannot be exaggerated. In the event of a simultaneous death, or if Frick should die after Yourcenar without leaving instructions regarding a successor, Yourcenar appointed her Parisian friends Jenny de Margerie and Emmanuel Boudot-Lamotte to step in. Gone were Edmond Jaloux and “best friend” André Fraigneau, both of whom had proven too sympathetic to the Nazi regime during the war. Yourcenar also took this opportunity to switch from her previous attorney to Frick’s trusted childhood friend Ruth Hall. To complete her legal business, Yourcenar stated her wish to be buried, should she die in America, “in the little cemetery of Somesville (Mount Desert Island, Maine) and in the cemetery of Chamblandes on Mount Pèlerin in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland, should I die in Europe.”18 This “little cemetery of Somesville” is, of course, the one right next to Hysom Cottage. Mount Pèlerin, overlooking Lake Geneva, is located just outside Lausanne, where Yourcenar lived while her father was treated for cancer. Jeanne de Vietinghoff is buried a few kilometers away in the cemetery of Jouxtens-Mézery.

The matter of adopting a child does not arise again in the documents at our disposal until early February 1949, when Yourcenar wrote a long letter to Marianne (Mosevius) Levinsohn, now living with her new husband in the Bronx. Levinsohn and her husband had decided against starting a family right away. Yourcenar’s response to that decision illustrates in part the ability to put herself in someone else’s shoes that she had tried to inculcate in her student with regard to literary texts: “I believe that it is very wise of you to put off having a child until later. Every period of life tends to be transformed or modified so quickly that it is essential to enjoy and experience it completely while one is going through it. And happiness for three (whether greater or lesser, that is not the issue) will never be exactly the same thing as happiness for two.”19

On the topic of children, Yourcenar then goes on to say,

As far as Grace Frick and I are concerned, our plan to adopt a child is still on, but for me the S.L.C. experience will have to be over, and we will have to have solved the problem of a more or less permanent home. What I would especially hope to do is to return to Europe for a year or two and adopt a European child over there. But immediately the great problem of knowing how, and in what tradition, to raise the child would arise: I have a prejudice against American education as it is presently conceived that grows stronger every day, but I cannot say that European education, in view of today’s universal chaos, has given very good results, either.20

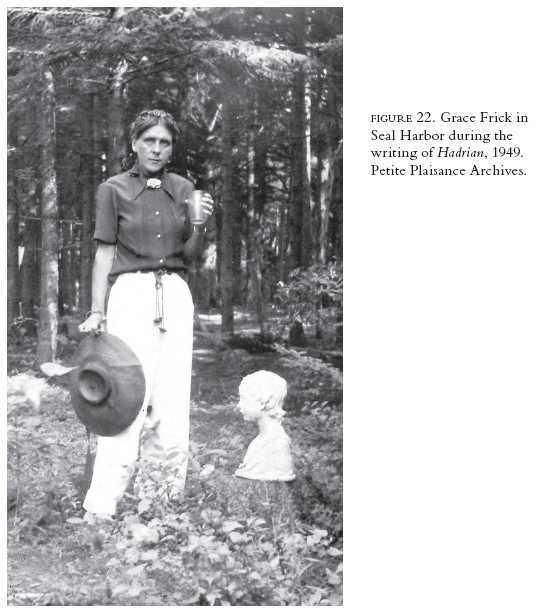

Less than two weeks after this letter was written, Yourcenar and Frick would be vacationing together in New Mexico during interim week at Sarah Lawrence. On January 24, 1949, the famous trunk containing old fragments of the Hadrian manuscript had arrived at 549 Prospect Avenue, where Yourcenar, atypically, was holding down the fort all by herself. Frick was caring for her maternal aunt Georgia Horner, who was undergoing cancer surgery in California. On February 10, from their opposite ends of the country, Marguerite and Grace made their way to New Mexico, reuniting in Santa Fe. Yourcenar wrote nonstop on the train as if the floodgates had opened, unleashing a narrative torrent. From this day forth for the next two years the daybook would give a detailed account of daily progress on a book that for twenty-five years had been dreamed of and attempted, despaired of and abandoned, over and over again.

Hadrian swept both Marguerite and Grace into its vortex. Frick chronicled its development with meticulous daily precision, noting along the way that they discussed the book while picking berries in Seal Harbor or read the latest pages aloud together over tea and popovers at Jordan Pond House. Grace usually read and commented on the manuscript in five- to ten-page batches, which were often the output of a day’s work.

She did research, alone or with Yourcenar, in every substantial library from New York City to Bangor, Maine: “Grace is marvellous [sic],” wrote Yourcenar in March of 1949.21 Frick helped her partner revise and tighten whole sections of the book upon their completion. On August 26, 1949, for example, after a day for which the agenda bears four joyful crosses in the evening quadrant, “M.Y. and Grace finish reading of main text of Terra Stabilita together (through Achievements) by spending entire morning alone in M.Y.’s bedroom.”22 There were almost always guests, and the couple sometimes worried about what they would think. On August 28, with Miriam Tompkins visiting them in Seal Harbor, Grace wrote,

M.Y. continued revision of Terra Stabilitata [sic], the tail-ends of such revision. Both of us conscious that we were talking much aloud of what must sound like too mechanical a process of revision, but both determined to use the time for what could be done in a period not conducive to creative work on M.Y.’s part. Actually, we managed to have a very enjoyable afternoon, G. slowly sweeping living room, meanwhile, discussing the actual cause of lack of clarity in a few sentences, the reason being, as nearly always in cases of obscurity in the statement, a lack of certainty about one or more facts on which the statement should have been based. Once having rectified the number, for example, of “philosophes” who would rightly be termed “errants,” the sentence fell almost as if automatically for her into its present, and correct, form.23

Eventually, of course, as the book advanced toward publication, there would be galleys and page proofs for the women to pore over and correct.

Yourcenar paid homage to her partner’s help in “Reflections on the Composition of Memoirs of Hadrian,” published in post-1951 editions of the novel. While her encomium is beautiful and heartfelt, it exemplifies the author’s tendency, evident also in what she wrote to Marianne Levinsohn about her and Frick’s adoption plan, to dispense as quickly as possible with the strictly personal and couch her remarks in more generalized terms:

This book bears no dedication. It ought to have been dedicated to G.F. . . . , and would have been, were there not a kind of impropriety in putting a personal inscription at the opening of a work where, precisely, I was trying to efface the personal. But even the longest dedication is too short and too commonplace to honor a friendship so uncommon. When I try to define this asset which has been mine now for years, I tell myself that such a privilege, however rare it may be, is surely not unique; that in the whole adventure of bringing a book successfully to its conclusion, or even in the entire life of some fortunate writers, there must have been sometimes, in the background, perhaps, someone who will not let pass the weak or inaccurate sentence which we ourselves would retain, out of fatigue; someone who would re-read with us for the twentieth time, if need be, a questionable page; someone who takes down for us from the library shelves the heavy tomes in which we may find a helpful suggestion, and who persists in continuing to peruse them long after weariness has made us give up; someone who bolsters our courage and approves, or sometimes disputes, our ideas; who shares with us, and with equal fervor, the joys of art and of living, the endless work which both require, never easy but never dull; someone who is neither our shadow nor our reflection, nor even our complement, but simply himself; someone who leaves us ideally free, but who nevertheless obliges us to be fully what we are. Hospes Comesque.24

Michèle Sarde has called Hadrian the couple’s child, noting Frick’s extraordinary role in the book’s gestation.25 Perhaps not knowing it would be their only one, the women went steadily about fulfilling the conditions that Yourcenar laid out in her letter to Levinsohn. In the fall of 1950 they bought a farmhouse on a quiet lane in Northeast Harbor. By March of 1952, having been in Europe for ten months, they had made a good dent in the year or two that Yourcenar had hoped to spend seeking out a child abroad. With Mémoires d’Hadrien finally published in France to overwhelming acclaim, the women were more secure financially than they had ever been. Leaving France, they began a two-month stay in Rome. Not only were they returning to the Mediterranean land of their first passion, they would be exploring in reality the hub of an empire they had occupied in fiction for two blazing years of their life.26 But they may also have been looking for a child in the country where they once sealed a lovers’ pact with a pair of gold rings. Consigned to their daybook that spring was the address of Save the Children in Rome.27

Why then did the adoption project fall through? Certainly these women who walked the streets of Northeast Harbor arm in arm in the repressive 1950s would not have been cowed by the prospect of social disapproval. As Charlotte Pomerantz Marzani noted about Yourcenar at Sarah Lawrence, “I think she knew about the rumor circulating that she lived with a woman. Basically, she couldn’t have cared less about people knowing this and saying that she was a lesbian.”28

What Yourcenar told Marianne Levinsohn in approving her decision to put off having children may have gained additional meaning as she and Frick learned more and more about the atrocities of World War II; “I seem to be preaching egoism,” wrote Yourcenar in 1949, “but in the highly threatening world we live in, thoughtful egoism often ends up seeming to me the only wisdom, and the only prudent form of kindness.”29

Of course, Frick and Yourcenar were not getting any younger—they would both turn fifty in 1953. In later years, as biographers have emphatically noted, Yourcenar showed little fondness for children in general. Josyane Savigneau went so far as to speak, and not without reason, of a “repulsion for procreation,” noting Yourcenar’s membership in the Association for Voluntary Sterilization.30 One day in August of 1983 Yourcenar did not shy from saying “I don’t much care for children.”31 They could be so terribly conventional, even mean. Asked whether she herself had ever been tempted to have a child, she said pensively, “For two weeks . . .”32

Grace, by contrast, never lost interest in children, and living as she did in a small island community, she had many opportunities for close contact with them. Whether it was parties arranged to teach young ladies (or gentlemen!) the finer points of serving tea, or group readings on the veranda of the latest local author’s children’s book, or celebrating an exotic foreign holiday with local youth (to say nothing of the boys who always helped out around the house), Frick filled the couple’s life with children. She and Yourcenar even taught some of their young helpers, boys of nine or ten, to make French bread for household consumption!

One boy in particular, David Peckham, whom the couple had met when they were renting 5 Harborside Road in Northeast Harbor, became almost a member of the family in the 1950s. When Frick and Yourcenar’s adult friends would come to the island for a few days, David was right there with them for boat rides, seaside adventures, and special treats. As Frick wrote in September of 1955, for example, when the Minear family was visiting, “Children went climbing in Cove by Rock End Dock, David Peckham delightedly joining the party and particularly enjoying the company of Anita, who is about a year older than he is. . . . 400 All to Jordan Pond, including David Peckham.”33 David was a tutelary spirit, as Frick wrote to her six-year-old niece Pamela Frick, with his “big dark eyes and nice smooth olive brown skin; very handsome he is, and a pleasure to have around.”34

In early 1956 Grace would write that David and another local boy were “here to work. After they brought wood they popped corn and helped mix popovers for tea. Very pretty, David’s face, growing thoughtful over the Swedish candle which I had him light.”35

David used the money he earned working at Petite Plaisance to buy his first bicycle. He came to speak with me about Grace in July 2008 at Petite Plaisance, by which time he was director of maintenance at New Jersey’s Fort Dix. He launched the conversation by saying that Frick had had an important influence on his life, particularly with regard to his desire to broaden his horizons. His mother had been a reader, too, so he was used to living amid books, but Grace brought a new dimension to his inclination to learn. He could not recall any of the episodes involving him that Frick had noted in the daybook, but he remembered precisely how she had taught him to build a fire and bake bread. Peckham described his childhood self as having “a sort of Downeast, blue-collar association,” which makes him a fairly typical observer of what for many year-round villagers was a highly unusual household. In his young eyes, “what these two were doing here was really weird. And they’d have you do things. . . . Like, Grace would have you put coffee grounds in the soil and I forget what other kinds of stuff, but it all seemed weird at the time. They didn’t do things the way that normal people did. What I called normal at that time.”36

Another thing that struck Peckham very vividly was the sense of disorder at Petite Plaisance. Pointing to the mantelpiece, with its elaborate Directory clock amid fireplace matches and postcards set there many years earlier, he confided, “For me it was chaos. . . . There were books everywhere, papers everywhere, notebooks everywhere, things everywhere.”37

Peckham then shared some thoughts about Frick that he had written down in preparation for our meeting:

I found her very forgiving, very patient. She would explain things and then explain them again if you needed her to. She wouldn’t worry about you making a mistake as long as you were doing it—that was the important thing. Try, even though you might make a mistake. Another note I made was, she was always teaching. There was never a thing that we did that she didn’t explain thoroughly why we were doing something, what the basis was, and what would happen if we did it correctly. Her teaching came through every time. But the biggest thing that I remember is working around the grounds. With her. With her instructing me about this flower and that flower and this bush and that bush, all kinds of strange things—at least I thought they were strange at the time. She would point me in the right direction and tell me to do this and this and this, and I’d go off and do it.38

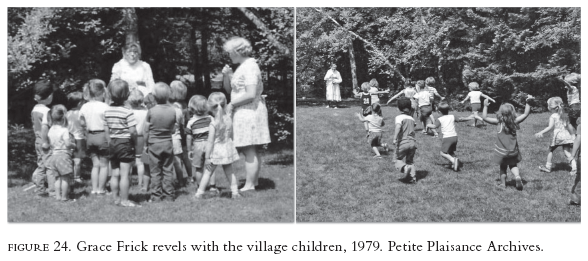

Grace Frick’s desire to involve herself with children never waned. Two color photographs saved and probably taken by Marguerite Yourcenar, tiny in size but enormous in their poignancy, show Grace in a far corner of the back lawn at Petite Plaisance, attired in a high-collared, flowing white dress. In the first, she is surrounded by a clutch of little girls and boys who listen with rapt attention to instructions that Grace seems to be giving them. A young female teacher surveys the scene, holding one child’s hand, from the rear of the group. In the second snapshot, the children jubilantly dash across the lawn toward a smiling Grace who clasps in front of her body a long, straight stick that seems to be the object of their joyful chase. On the back of both these pictures, Marguerite wrote, “The last photograph of Grace with the nursery school children in the garden at Petite Plaisance, late August 1979. She died on November 18.”