CHAPTER 20

On the Road Again

1953–1954

To move, to breathe, to fly, to float,

To gain all while you give,

To roam the roads of lands remote:

To travel is to live.

—Hans Christian Andersen

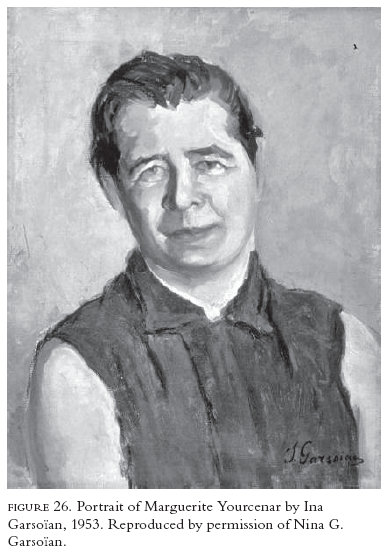

MARGUERITE YOURCENAR’S FINAL SEMESTER OF teaching at Sarah Lawrence ended in the spring of 1953. For the next two years she and Grace Frick were in constant motion. They moved out of the sublet in Scarsdale on April 30, and Yourcenar rented a room in Bronxville for the remaining few weeks of the academic year. She was also posing for Ina Garsoïan’s portrait at the time.

As the couple would soon leave again for Europe, Grace went to Kansas City for a week. On May 20 Marguerite double-underlined “Grace coming back” in the daybook and took the train into New York to meet her at the station. As they often did on the occasion of such reunions, they spent a few days in the city seeing friends, dining out, and taking long walks in Central Park.

There were many reasons to return to France—the Marquis de Cuevas’s ballet based on Hadrian’s Antinoüs was opening in mid-May, Yourcenar’s 1939 novel Le Coup de grâce had been reissued, Électre ou la Chute des masques would soon be staged in Paris—but the couple’s first stop would be England, a country they both loved and had not yet visited together. They would sail from Halifax, Nova Scotia, aboard the SS Newfoundland on July 21, arriving in Liverpool a week later.

Once again they were on the trail of a certain emperor, prompting Natalie Barney to quip, “Your card from Hotel Hadrian amused me. Is it he who pursues you or you him?”1 The pair traveled almost immediately to Hadrian’s Wall, staying near Hexham. They remained there for five weeks, exploring the wall, making day trips, and visiting the archaeological excavation under way at Corbridge.2 From Hexham they headed south toward Port Sunlight, whose Lady Lever Museum housed a stunning early second-century statue of Antinoüs. En route to the west coast they stopped in Brontë country, which Grace had visited twenty-five years earlier. Both she and Marguerite loved the Brontës. When asked to identify her important female predecessors, Yourcenar once said, “[Looking back] we see quite a few women poets who expressed their emotions and a few women novelists who recounted the sentiments and emotions that moved them most deeply. I believe that the greatest among them, those whom one can cite with the most admiration, are the Brontë sisters.”3 Back home in Maine the couple would place images of Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë on the bureau in one of their guest bedrooms.

It was during their leisurely visit to England, where the women could travel in relative peace, that two “unforgettable” images of Grace, the first already noted, imprinted themselves in Yourcenar’s memory. As the author reminisced near the end of her life about that British tour,

I see a young woman, with a young Sibyl’s features, sitting on one of the gates that separate the fields from the pastures over there; we’re at the foot of Hadrian’s Wall; her hair is waving in the wind from the mountaintops; she seems to embody that expanse of air and sky. I see the same young woman in a four-poster bed in an old, run-down house in Ludlow talking about Shakespeare, whom she imagines rehearsing with his actors, or rather speaking to him as if she were there.4

Grace was eager to show Marguerite the Norman fortress at Ludlow, which had acquired an Elizabethan cast when held by the Crown. She had first seen that medieval castle, east of Birmingham, in 1937 after visiting Margaret Symons in Wormelow. It held literary as well as historical interest for her, reputed as it was to have provided a venue in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries for traveling performances of Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Milton.

From England the couple made their first trip to Scandinavia, a region that would hold a special place in their hearts for the rest of their lives. They were drawn to Denmark, as to Sweden, Norway, and Finland, by the promise of paid lectures. At Copenhagen’s French Institute, Yourcenar’s topic was “The Novelist Confronting History.” She also lectured during that tour on the mythical character Electra, subject of her soon-to-be published play.

On October 22 they took a train ferry to Stockholm for a round of luncheons, book signings, and interviews. While based in Stockholm they traveled for two days to Oslo, where Yourcenar spoke at the Nobel Institute. On November 15, with Grace nursing a sore throat and Marguerite coming down with a cold, the women left for Finland on the SS Bore II. Still under the weather, they spent the next morning in bed deciphering four Finnish newspapers using the Finnish translation of Hadrian as their Rosetta Stone!5

Back in Stockholm, where they spent another month, they got their first taste of Sweden’s lavish holiday festivities. On December 6 they rode through the Old City to watch the Saint Nicholas celebration in the streets. In the square near the Royal Palace and on the palace bridges there were beautiful illuminated spruce trees. Christmas itself they spent back in Copenhagen before returning to Paris on December 28. On New Year’s Eve, declining two dinner invitations, they had supper by candlelight alone in their hotel room “skolling” the new year à deux.6

That New Year’s Eve turned out to be the calm before the storm. Throughout their Scandinavian travels, both Yourcenar and Frick had devoted considerable work time to the long-delayed Présentation critique de Constantin Cavafy, which Gallimard grew more and more impatient to publish as Cavafy’s literary executor, Alexander Singopoulos, grew less and less cooperative with regard to the project. Sets and costumes were also being designed for Yourcenar’s Électre, which would turn into another battle royal. But the worst cataclysm occurred on March 15, 1954, when Yourcenar’s American passport was summarily canceled. Both women had renewed their passports without difficulty in Rome two years earlier. Frick sailed through the process this time, too. Had Yourcenar’s celebrated novel about an emperor’s love for an adolescent boy earned her more than a literary reputation?

As we saw in chapter 9, an American era of suspicion had already begun back in 1941, when an embassy official in Montreal inexplicably delayed the approval of Yourcenar’s new visa. By 1954 McCarthyism was in full swing. As Patricia Palmieri has noted, “Attitudes and policies toward professional women narrowed throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. In the era of the Cold War, any form of social deviance was threatening.”7 Homosexuals, in particular, were seen as both sexually and politically subversive, and witch hunts were conducted by congressional committees throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Progressive Sarah Lawrence College was targeted by several investigations. The writer and activist Muriel Rukeyser, a member of the literature faculty, and the sociology professor Helen Merrell Lynd were both accused by the American Legion of communist involvement.8 Lynd was questioned by the Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security. Years later Yourcenar would say that students “were very much aware of McCarthyism, with its attendant persecution of foreigners and foreign-born Americans. Many of the students in the school where I taught felt as threatened as I and other teachers did.”9 Altogether, eighteen faculty members were pursued by congressional committees, one of whom invoked the Fifth Amendment and resigned.

Another member of the faculty, Margaret Barratin, was in Paris in the spring of 1954 serving as director of the college’s Students in France program. Her husband had been dismissed from the United Nations “as a sympathizer with persons unfairly investigated” by a Senate committee.10 Barratin immediately leapt to the support of her colleague, who had given two lectures to Sarah Lawrence students over the previous few weeks.11

Two days later Grace Frick vouched for her companion’s residential and professional ties to the United States in more extensive detail.12 Yourcenar’s even more explicit letter in her own defense, also written on March 22, goes all the way back to her birth in 1903. Not content to place the letter in the mail, Yourcenar delivered it to the embassy in person.13

Frick’s real sentiments about the matter were expressed, with considerably more vehemence than in either of the couple’s pleas to the consulate, in another letter written on March 22, 1954. It was addressed to the first member of the U.S. Congress who dared to publicly denounce the tactics of McCarthyism, Margaret Chase Smith.14 In June of 1950 the senator from Maine had distinguished herself, in a speech known as her Declaration of Conscience, by decrying on the floor of the Senate the character assassination, intimidation, and bigotry being practiced by her Republican colleagues. Frick had attended a talk that Smith gave at the Northeast Harbor High School in 1952.15 She knew her words would not fall on deaf ears.

At issue was the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, also known as the McCarran-Walter Act. President Harry S. Truman vetoed this legislation, believing it to be inconsistent with American values, but Congress overrode his veto. In 1952 the author Mary McCarthy characterized this “unjust law” in a manner pertinent to Yourcenar’s plight, evoking “the many absurdities and cruelties of the McCarran Act,” among them “the arbitrary refusal of visas without any kind of due process.”16 Grace Frick, for her part, told Margaret Chase Smith that she found the act’s language “antithetic to all individual cultural endeavor not affiliated with some recognized institution or agency,” calling its methods “terroristic.”17

The passport debacle, ironically, was resolved not by Senator Smith but by the expatriate lesbian Natalie Clifford Barney, whose mere phone call to embassy officials cleared the impasse. Grace, still appalled by the injustice, thanked her “dear and vigorous friend” on March 23: “I am desolated to think that such a routine and clearly-defined case could not be settled without pressure from above. What of the hundreds of people who have not a Natalie Barney to fight for them by telephone, and early on Monday morning, the very first business day after our defeat? Though born of a Republican family I am becoming more and more a Jeffersonian Democrat.”18

Yourcenar never forgot the service rendered her by Barney that March. She spoke of it no fewer than three times in her future correspondence with the famed salonière. In 1962, for example, she wrote to thank Barney for a gift bestowed on her and Grace, adding, “Nor have I forgotten, especially, your assistance when I found myself confronted at the American Consulate by an ignorant McCarthyist official who refused even to read my passport.”19

Natalie and Grace shared a desire to be of service to others generally and to Marguerite Yourcenar in particular. Their mutual friendship and affection, keen from the very beginning, deepened in the wake of the passport episode. That April Natalie brought her longtime lover Romaine Brooks to tea with Grace and Marguerite at their hotel. She had asked to bring her old flame the Duchesse de Clermont-Tonnerre—to whom Barney remained devoted all her life—and a Baroness Gautier, but Frick and Yourcenar apparently preferred to meet Romaine alone.20

They would soon be leaving France for a four-month stay in Germany, but even while they were still in Paris they kept in touch with their generous friend by way of notes and postcards. On May 6, 1954, Marguerite informed Natalie that preparations were under way for a performance of Électre but that she was looking forward to leaving all that behind for a while. Yourcenar had loved Paris, its museums, its parks, its musical and theatrical offerings, since she was a child, but the attraction of the city was beginning to be dimmed by the ever more numerous professional obligations that always awaited her there. With regard to the work involved in finding a venue and choosing cast members for Électre, she wrote, “It is all extremely tiring, and I am delighted to be leaving and not to have to start again until September.”21 It was not until seven months later, in the rural calm of Fayence, that Yourcenar could say that “the Parisian fatigue is slowly going away.”22

Natalie’s notes and letters, which she often signed “Yours in tender friendship” or “Ever yours with love,” were frequently flirtatious in tone, and there is no doubt that the women’s friendship was tinged with a certain romance. Not surprisingly, given her candor regarding her sexual preferences, Barney often tried to engage her friends in lesbian-oriented topics or activities. It was with Natalie, as we have seen, that Marguerite and Grace attended the European premiere of Four Saints in Three Acts. It was also Natalie who lent a copy of Gertrude Stein’s “coming out story” to the couple early in their acquaintance. Barney liked nothing better than to sprinkle her letters with allusions to Sappho, Gide, or other literary icons of a certain persuasion. She tried repeatedly to put Grace and Marguerite together with a bisexual English friend who had written an erotically charged lesbian novel that was published by the Hogarth Press in 1949. Dorothy Bussy’s Olivia told the story of an adolescent’s passion for the headmistress of an exclusive girls school very much like Les Ruches in Fontainebleau, which both Bussy and Barney had attended.23 Before Marguerite and Grace left for Germany, Natalie wrote to tell them that a film based on her “old schoolmate’s” novel was being shown in New York under the “fallacious title” The Pit of Loneliness.24 Fallacious, that is, not only because it was chosen to echo the title of Radclyffe Hall’s Well of Loneliness but also because Hall’s novel was so obviously based on none other than Natalie Barney and her literary salon on the rue Jacob.25

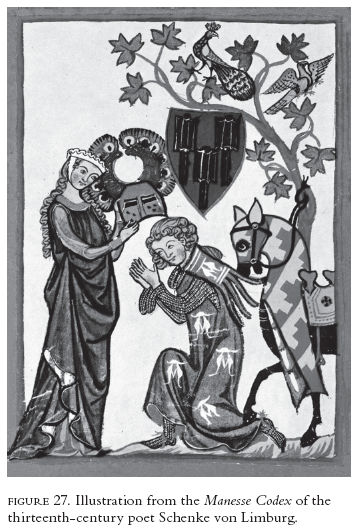

Marguerite would sometimes respond in playful ways to Natalie’s lesbian gambits, as she did shortly after she and Grace arrived in Heidelberg that spring. Knowing the Amazon’s love of horseback riding, and having heard the story, by this time legendary, of a youthful Natalie dressing up as a page boy to seduce a notorious Parisian courtesan, Yourcenar and Frick sent Barney a postcard image from the Manesse Codex, a medieval illuminated manuscript of poetic ballads and “portraits.” The one chosen for Natalie depicts a red-cheeked young knight kneeling at the feet of his lady love, a colorfully draped steed impatiently tied to a tree at his side.26 There is no mention of the image in Yourcenar’s short note, but the unspoken message was undoubtedly received by the postcard’s witty addressee.

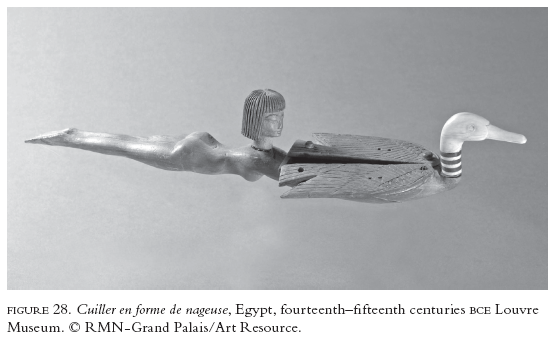

In early June 1952, the year they all first met, Barney had suggested that Yourcenar and Frick might like to hear the nightclub owner Suzy Solidor read from The Songs of Bilitis.27 This collection of lesbian erotic poems was supposedly written by a contemporary of Sappho’s and translated from the Greek for the first time in the late nineteenth century by Pierre Louÿs. In fact, Louÿs wrote the poems himself. Before their spring 1954 departure from Paris, as it turns out, Frick and Yourcenar took in a performance of the operetta Bilitis at the Théâtre des Capucines—without inviting Barney to join them. Yourcenar mentioned the event on the front of a postcard that can only have been chosen with Natalie in mind. Sent from the spa town of Bad Homburg, it bore the image of a wood and ivory carving of a naked girl swimming behind and holding onto a duck. This astonishing artifact from the Louvre, entitled Cuiller en forme de nageuse (Spoon in the form of a girl swimming), appears to have been an Egyptian makeup spoon. Underneath the image—that is, on the front of the postcard—Yourcenar wrote, “Grace and I saw Bilitis by chance at the Capucines: it was dreadful and not even amusing.”28

On the other side of the same postcard, sent in late June, Yourcenar finally answered a question that Barney had been asking her since April: Would she be willing to advise her regarding a play she had placed with a friend’s theater agent?29 Barney called it such “a very hazardous enterprise and subject” that she didn’t “quite like to think of even a Parisian audience’s reactions to it,” so one can imagine its provocative, probably autobiographical subject matter. In early June she mentioned it again: “Lacking your advice on whether you considered it ‘jouable’ [possible to stage] I asked my old friend Paul Geraldy to read it, and he found it a new but dangerous subject for anything but an ‘elite.’”30 Two weeks later Barney reported that Geraldy was going to offer her dangerous play to the Capucines or to the Mathurins next door, and she thus once more pleaded with Yourcenar to read the script: “If you find my play sufficiently interesting, perhaps I would do better to publish it than to expose it to such affronts? But do you ever have the time to read it and advise me? Or even for us to meet again?”31

Yourcenar, whose artistic ideals bore little resemblance to Natalie’s, responded in a way that engaged with her friend’s request for counsel while evading the main issue: “I will read the play with great interest, but I can already caution you not to give it to the theater—unless you find an exquisite little stage. That sort of thing is made for small theaters with an eighteenth-century decor à la Prince de Conti or Gustave III and not for the Capucines. The ‘light’ genre runs even more risk than the tragic; do not imprudently expose Psyche’s wings.”32 Yourcenar’s metaphorical comment about the wings of the Greek goddess who, after being married to Eros, came to serve Aphrodite was undoubtedly inspired by the wings of the Egyptian carving pictured on the front of the postcard.

Grace and Marguerite never did manage to see Barney that summer. The manuscript of Natalie’s play languished at 20 rue Jacob, from which location she offered to have her assistant deliver it to Yourcenar in late September.33 Not until the following June did Barney write to say that she had given up on having her play mounted.34

When Barney got a bee in her bonnet, she could be extremely persistent. This was equally true, if not more so, when she was offering advice as when she was seeking it. Indeed, a tendency to blur the line between helpfulness and meddling is yet another characteristic that Frick and Barney shared. When Grace was translating Hadrian, for instance, Natalie made several suggestions that, judging from the silence with which they were met by their recipients, were somewhat less than welcome. In one letter Natalie cautioned Grace somewhat cryptically, “Don’t rush out your tinsnips with too much ‘fervour’ is the advice of this old amazon who bears you both so much keen interest and sympathy!”35 She repeatedly urged Grace to seek translation assistance from André Gide’s close friend and English translator Dorothy Bussy or Elizabeth Sprigge, biographer of Ivy Compton-Burnett.36 Frick and Yourcenar finally succumbed to Barney’s insistence that they visit Bussy at her villa, La Souco, in Roquebrune, but they did so only after the Hadrian translation came out.37

Barney’s many questions about Frick’s progress were, of course, an expression of interest in her friends’ life—“I’m so glad that the translation is progressing ‘admirably.’ And without too much strain and stress? When do you expect it to appear? This should prove somewhat liberating.” “And will you be heart whole and translation free to return to us in Paris this coming spring?”—but they were also a subtle means of taking sides.38

Barney trod on more dangerous ground with regard to another of her insistent queries, issued primarily when Yourcenar and Frick were back in Maine: “When, oh when, will you return?”39 “When will you come back to us?”40 “When are you both returning to France, and to me?”41 “Are you coming this summer? In the fall? On what season may we pin our hopes of seeing you?”42 “Come back to me soon.”43 That she considered Grace responsible for Yourcenar’s much-lamented absence from Paris is intimated in a letter from the spring of 1955. Natalie had decided that Yourcenar should receive the French Legion of Honor and had begun plying her various connections to French officialdom with an eye toward achieving that end. She had apparently become concerned that Yourcenar’s U.S. citizenship might pose an obstacle to the receipt of that award:

May that worrying passport, making you and not leaving you an American, not stand in the way of this, nor of your return to us after Grace’s U.S.A. Xmas. . . .

But wouldn’t it be more convenient to regain your French passport, for if you intend to spend most of your time out of the U.S.A. you could always return there for 3 months at a time as tourist lecturer or teacher?44

Although Natalie did allow that dual citizenship would be “the best solution,” Grace undoubtedly viewed Barney’s suggestions regarding her partner’s nationality as an incursion into her territory. It was around this same time—perhaps not coincidentally—that Natalie signed two of her letters to the couple in a curious manner. On June 20, 1954, it was “And give Grace my friendship, so well differentiated between the two of you, as ever and ever your admirer and aff[ectionate].”45 Ten months later, she signed off with “faithful and diversified love.”46

Frick did not hold a grudge against Barney, however. Her letters continued to be warm and engaged. Yourcenar, for her part, tended to sidestep the issue of her residency, writing Barney, for example, from Petite Plaisance in July of 1955 that “in a way, I feel as close to my friends here as I did in Fayence, or even at the St. James, for I think of them often and especially of you.”47 Creative work, moreover, always provided an unassailable reason for remaining at Petite Plaisance. In a Christmas note to Barney that same year, Yourcenar wrote, possibly referring to Grace’s translation of Le Coup de grâce: “You ask when I’ll return to Europe. As soon as it’s possible to, but the book will have to be completed first.”48 She signed that letter, “I embrace you affectionately. Grace does, too.” As if to prove it, Frick adds a postscript in her own hand: “We are sending you a whole battery of photographs, apart, which will probably recall to you the pines of Maine as you knew them. Love to you, Grace.”