CHAPTER 21

Continuing the Journey

1954–1955

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen.

—John Keats

ON MAY 9, 1954, GRACE Frick and Marguerite Yourcenar left Paris on the Orient Express bound for Stuttgart. Yourcenar was unwell for several weeks in Germany, which she ascribed to fatigue and heavy German food. How difficult parts of the summer were may be judged by what she wrote to Constantine “Didi” Dimaras, her Cavafy translation collaborator. She had hoped to see Dimaras in Athens but wrote in June to ask if they could meet somewhere closer to her current location. “I envy you Olympia,” she wrote, “one of the most beautiful places in the world. I would gladly trade the whole Rhine River for one drop of water from the Alfeiós.”1

Yourcenar’s health had improved by early July, when she and Frick took a train ride along what Grace called the “magically beautiful valley” of the Main River heading toward Würzburg in northern Bavaria.2 They arrived there just in time to hear the last concert of the Mozart festival, which was given out of doors in the torchlit Court Gardens of the lavish Würzburg Residence, now a UNESCO World Heritage site. Most of the rest of the summer was spent in Munich, where Yourcenar finished writing “Oppian, or the Chase” and “That Mighty Sculptor, Time.”3

Near the end of their long stay in Germany, the couple treated themselves to several outings in southern Bavaria. Having spent so much time in big cities over the previous year, they were eager to seek respite in nature. Indeed, it was in the mid-1950s that they both began to feel that the natural world was under threat.4 On the morning of September 5, 1954, the women traveled by train for a lakeside “breakfast-lunch” in the village of Starnberg. From there they proceeded to the alpine lakes high above Mittenwald.5 They were so taken by the beauty of the lakes, by day or by shimmering moonlight, that they returned to cross Lake Starnberg several times.6

Close to midnight on September 10 back in Munich, the women were setting off on foot to mail a batch of galley proofs to New York. Just as they were leaving their hotel, a car pulled up outside. The man in the front seat was having a heart attack, and his companion was crying out for help. Grace dropped her package and rushed to the car, dispatching Marguerite to get some brandy. It was the actor and director Reinhold Schünzel, best remembered as the sinister scientist in Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious. His wife Lena was in such distress that Frick went with her to the hospital and escorted her back to her home. Reinhold could not be revived.7

Frick and Yourcenar left Germany for Paris via night train on September 22 to oversee the mounting of Yourcenar’s play Électre ou la Chute des masques. They immediately found the actress Jany Holt unfit for the part of Electra. The actor chosen to play Orestes was equally objectionable. New auditions were held for these big roles, but the casting changes Yourcenar insisted on never got made. As relations with the play’s director, Jean Marchat, and the theater owner, Mme Harry Baur, grew increasingly adversarial, Yourcenar withdrew all support, filing suit against Marchat and the Théâtre des Mathurins. Thus began the “Electra affair.” Not until March of 1956 was the lawsuit decided in the author’s favor—to the tune of 500,000 francs in damages.8

With high hopes of enjoying a break from the demands of Paris, the couple boarded a night sleeper for the Mediterranean resort town of Saint Raphael on December 10. It was not an ideal time of year for a vacation on the French Riviera. Both women were exhausted, and Marguerite fell ill in their poorly heated room at the Hôtel Continental. Grace set off on her own in a taxi for Fayence, where Chick Austin had offered them use of a home he owned in that Provençal village about twenty-five miles northwest of Cannes. According to Austin’s biographer, the four-story villa in Fayence was located “at the top of the hill in the town, near the hôtel de ville and the local café.”9 Frick was struck by the beauty of the sparsely furnished home, but how would they heat it? Her companion, seeing the place for the first time three days later, was less favorably impressed.10 After checking out rental options in Saint Raphael, they nonetheless decided to accept Austin’s offer.

As when Grace and Marguerite had moved into Petite Plaisance four years earlier, the first thing they did was to buy a gas stove for their new dwelling. That appliance, a batch of groceries, and the couple’s two trunks and eighteen suitcases would be delivered to Fayence by the hardware store in Saint Raphael. On December 19 they themselves took the 4:30 p.m. bus to their new lodgings. Things did not go smoothly at first. It was very cold, running water at the villa was intermittent at best, and there was no water service whatsoever at night for the entire first week of their stay. To make matters worse, the bone-penetrating mistral was afoot. As Grace wrote in the daybook on December 22, the “mistral began howling in the chimney in the early morning hours, and shrieking through the windowless houses adjoining and in back of us.” There was a “terrifying clatter of shutters banging and broken tiles hurled from roof tops all around us.” Finally the weather calmed, and Marguerite began to recover from what turned out to be a bout of bronchitis.

On Christmas Day, their first full day of warmth, the women began exploring Fayence. Dating back to the tenth century, the village is perched on a promontory and features steep, narrow streets. On their first outing, so that Marguerite would not have to do much climbing, they ventured only as far as the Château du Puy, built in the previous century. The next day, feeling more sure-footed, they followed a goat path to the highest point in Fayence and its old bell tower, from which they had a panoramic view of the surrounding countryside. Everywhere they went they went on foot, with Grace sometimes scoping out routes in advance to be sure they would not be too strenuous for her partner. One evening, with an iron roasting spit in need of repair, they walked the half mile or so to Tourrettes seeking out the local blacksmith. Frick’s description of that errand gives a glimpse of the kind of community the couple had decided to inhabit for a time. They found Monsieur Perrimond working at his forge, “very handsome in the evening light, and Madame finishing her laundry over the open air fountain. Her boiler kettle was still steaming over the small fire, and the dog lay comfortably before the blaze. Madame used cinders to whiten her linen, preferring the old process to boiling or bleach.”11 Sometimes they would stop by the forge after dark to help blow the fire, an act that can hardly have failed to resonate in the mind of an author who soon would start writing the story of a sixteenth-century alchemist-philosopher-physician. But what they most enjoyed on their walks were encounters with the flora and fauna. “Wild anemone, violets, a kind of gentian, golden buttercup, narcissus, grape hyacinth, iris, and three tiny wild blooms” they could not identify were the bounty of one country stroll. On a trek to nearby Lacoste, they saw a “wonderful cascade of sheep flowing down the steep sides of the ravine to drink from the stream. Many black and dun brown in the flock, and many lambs, pink ears raised high.”12 They often returned from their walks carrying stray pieces of furniture borrowed from nearby homes or cypress boughs broken off by the wind. Though they had lived in Fayence for only twelve days by New Year’s Eve, they kept up the tradition of an eggnog party, attended by local residents, workmen, and children whom they had already befriended. Reading Frick’s daybooks about the months spent in Fayence, one feels the women decompressing in that village whose night sky was a riot of stars.

As at Petite Plaisance, village children were always about. Troops of them would appear when the couple got a load of firewood, eager to carry the logs up the stairs and stack them in convenient wood boxes. Grace and Marguerite entertained them with “candle-light and shadows,” compensating them with cookies bought in Saint Raphael, where they went by bus to do their shopping. One sunny day all was quiet “except for tempestuous little boys mounting the wood and acting plays in the salon.”13 On another occasion, using saucepans and colanders for shields, the boys played “Caesar landing at Fréjus and defeating Vercingétorix (who rode in upon a stick of wood).”14

In addition to the neighborhood children, the women acquired an Irish setter named Mirah, “whom we seem to have adopted, collar bell and all.” Describing Mirah in the daybook, Grace mentions the superb German shepherd they befriended on Mount Desert Island before they bought Petite Plaisance: “She is not so beautiful as our Terry of Seal Harbor summers (the forester’s dog) but she has charms of her own, particularly at table, where she likes to sit high on her chair.”15 Next to dining with her adoptive mistresses, Mirah liked nothing better than to accompany the couple on their tramps about the countryside.

While they were based in Fayence, Grace and Marguerite also received a few grown-up human visitors: Yourcenar’s publisher at Éditions Plon, Charles Orengo and his wife, for example, and Alexis Curvers and his wife, Marie Delcourt. Curvers would soon find himself on the receiving end of one of Yourcenar’s lawsuits, but for now he was just a Belgian poet and printer who had come into the couple’s orbit the previous year.

One of Yourcenar’s projects that winter was an article commissioned by the French publisher Martin Flinker for a volume honoring Thomas Mann on his eightieth birthday.16 While Yourcenar was finishing her essay in mid-February, none other than Herr Mann himself was writing her a laudatory letter about Électre ou la Chute des masques, an inscribed copy of which she had sent to him several months earlier. Forwarded from Paris by Flinker, Mann’s handwritten letter reached Fayence on February 28. Frick described it as “giving very fine commentary on the play from a humanist point of view, and corresponding exactly to the author’s own views, to her great joy. Best of all, this letter was written by Mann before he could know of her article on him.” Relying on her graduate-school German, Grace roughed out a first translation of the text. The visiting Marie Delcourt later helped with some difficult words in the original and wrote out the whole letter in French.17 So precious was Mann’s expression of regard that the couple had multiple photostats made of both the letter itself and the envelope it came in.

Next on the guest list in Fayence were the Russian-born artist Élie Grekoff and his painter friend Pierre Monteret. Frick and Yourcenar went all out preparing for Grekoff’s five-day visit and Monteret’s shortly thereafter: cleaning and washing, shopping and cooking, borrowing or buying household items they would need. The timing was less than ideal: Marguerite was just recovering from another bout of bronchitis, Grace had a stubborn skin infection, and the mistral was gearing up for a weeklong assault. Grekoff arrived on February 16, and Marguerite made a pork roast that evening to welcome him. Grace describes what happened the next day in her daybook, mentioning two village boys whom she and Marguerite had taught to make crepes: “We had intended to have cold meat the next night with artichokes and crêpes, but Élie announced emphatically that he did not like crêpes, so we had to forgo them, although we allowed Robert Dei and Georges Brun to amuse themselves and us by making a big crêpe over the fire.”18

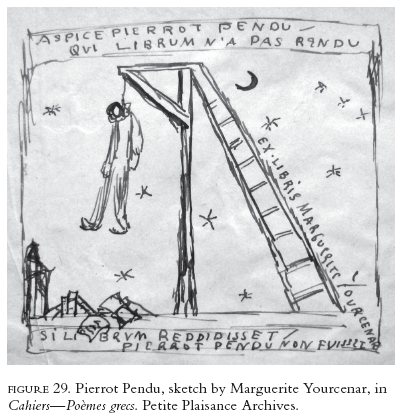

Grace had come up with the idea of asking Grekoff to design a bookplate for her partner based on one of Marguerite’s own drawings. As Sue Lonoff de Cuevas has explained, Yourcenar made at least five sketches over several decades beginning in 1922 of the traditional character Pierrot hanging from a gibbet and identified as “Pierrot Pendu.”19

No two drawings are exactly alike, but they all feature books lying underneath a scaffold and the following mostly Latin verse, which provides an apt sentiment for a bookplate: “Aspice Pierrot Pendu / Qui librum n’a pas rendu / Si librum redidisset / Pierrot Pendu non fuisset” (Behold the gibbeted Pierrot / Who did not return the book; / If he had given the book back, / He would not have been hung). So Yourcenar sketched a “Pierrot Pendu” for Grekoff, who, according to Frick, “immediately began to transform what should have been a wistful, rather naïve figure (based on medieval sculpture) into a pseudo-sophisticated, elaborately staged hanging of a modern pantomime figure. Not that he drew the figure itself, but in a rapid sketch he succeeded in eliminating most of what was wanted, particularly the books, which he said would be ‘very tedious’ to draw.” Alone in their room that night, Marguerite said to Grace resignedly, “He can never do that design with the simplicity required,” and Grace decided to withdraw her request.20

Grekoff caught a cold the next day and was ill for the rest of his stay. When he left on the afternoon of February 21, Marguerite “took to her bed,” worn out and somewhat dispirited. Hoping to relieve their feelings, Grace made popovers for tea!

Less than two weeks later, Pierre Monteret arrived in town, bearing a “disgruntled” letter from Grekoff to Frick, which they read aloud together. We don’t know the contents of that letter, and it is nowhere to be found in the archive at Harvard University. Grekoff may have resented the withdrawal of the bookplate request. There was obviously a certain testiness in the relationship between him and Frick at that time. The following year he would call her “an angel despite the appearance sometimes of something diabolical in her angelic intentions.” Grekoff also had the strange habit, which may have been his way of gendering his friends’ couple, of referring to the two of them in French in the masculine plural, thus tagging one of them as male; once he even addressed a letter to “Chère [feminine] Marguerite, cher [masculine] Grace, thereby reversing the gender roles that some might imagine them conforming to.21

The women had prepared a delicious-sounding dinner for Monteret’s first night: “roast chicken, braised tomatoes, rice; salad of endive, celery, cress, mayonnaise; wine, fruit, and date pudding with crème chantilly,” the latter served with lime-blossom tea.22 “We thought it good,” Grace reported in her daybook, but Monteret was unimpressed. His only comment was, “So you have no housekeeper of any kind?” Dinner the next night, as recounted by Grace, was nonetheless equally creative and abundant: “roast veal, braised endive, pommes de terre rissolées, salad, soufflé au chocolat (wine), infusion de tilleul, requested again by Pierre, fruit. (We forgot cheese both nights, though M.Y. had bought it specially for him. Maybe that is what he wanted!)”23

After Monteret left the next day, Grace and Marguerite climbed up to the roof of their tall building to regroup and watch the sun set. As Grace wrote in the daybook,

We sit in wonder at our failure to stimulate enthusiasm in our house and dinner guests of the past two weeks (Elie, Pierre, Longueville).24 (Tea guests were better.) None of them see why we like this house, in spite of the difficulty of heating it, and none of them seem to have any gusto about anything, not to mention their evident lack of interest in trying to know either the author or her work. Not a question, not an observation on her method of working, though she painstakingly inquired as to theirs.25

The peaceful surcease from the frenzied pace of life in Paris or Munich had given the two women a new appreciation of the value of their privacy. As Grekoff himself would note in a 1956 letter to the couple about their most recent stay in Paris—using what may be a subconscious allusion to the meals they cooked for him—they would share themselves more sparingly with others in the future: “So many people arrogantly thought that they would make a copious meal of your presence; a crowd of them came running, and you two hardly gave them a petit four.”26

Fortunately, Frick and Yourcenar’s trips to see friends around the region were more rewarding. One such was an excursion by taxi to Villefranche-sur-Mer, not far from Nice, for luncheon with Baroness Louise de Borchgrave. Borchgrave, a native of The Hague, had been a close friend of Marguerite’s father and had cherished his precocious little girl.27 In the daybook Frick calls Madame de Borchgrave “one of three daughters Stouts, a musical family whom M.Y. saw in her childhood both in Holland and on their summer visits to Belgium.” Providing a rare glimpse of Marguerite as a child, Borchgrave remembered—and Frick no doubt gleefully wrote down—that she had “tyrannized” over the children of Borchgrave’s sister Madeleine, “solemnly, giving them ‘lessons’ which they dutifully endured. She gave dictation to them by the hour.”28 It had been more than thirty-five years since Marguerite had last seen “Aunt Loulou.” She was very fond of Borchgrave and would keep up a correspondence, carefully sending her copies of her books, until Aunt Loulou died, at the age of one hundred, in 1986.

Marguerite and Grace also saw Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks at least three times during their four months in the Var. Barney arrived in Nice for her customary winter stay with Brooks at 11 rue des Ponchettes in late January. On Valentine’s Day the couple took a chauffeur-driven car to Fayence for tea with their friends. Two weeks later Grace and Marguerite went to Brooks’s beautiful apartment with its top-floor studio overlooking the Mediterranean and located next to the cliff where Nice’s old château once stood. They called on Brooks and Barney again in April when they were in Nice attempting to resolve what was for once a minor passport-related difficulty. Grace took advantage of that visit to ride the elevator to the top of the cliff and tour the castle gardens.29 Marguerite, always wary of heights, remained at ground level.

The next day the two women went by bus to the prefecture in Draguignan, hoping to iron out a bureaucratic wrinkle pertaining to the length of their stay on French soil. As Grace reports, that bus traveled “via the terrors of the Bargemon Road,” which, to make matters worse, was then under repair. Still subject to sudden spells of vertigo, “Gretie clutched Grace and all things clutchable,” thereby avoiding a dreaded bout of nausea. The Draguignan administrative center granted them a prolongation of their stay, but they would have to leave the country no later than April 16, one week after receiving their official papers.

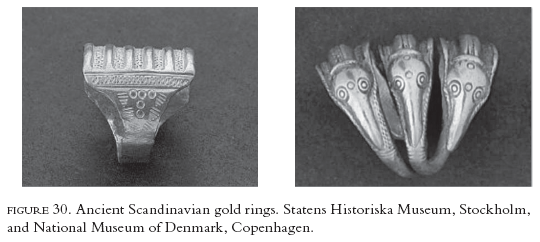

On precisely that date, having sold their stove and sent their heavy luggage on ahead of them by truck, the couple left Fayence, headed for Grenoble and beyond. Two days later they would land in their beloved Scandinavia. They were delighted to find themselves again in the streets of Stockholm’s Old City. It had been almost a year and a half since the couple’s last visit to the region, which had ended after nine days in Copenhagen on December 27, 1953. Grace and Marguerite had gone at least twice during that previous stay to the National Museum of Denmark, where they were captivated by some Iron Age—and perhaps not coincidentally, Roman Iron Age—gold rings. So much so, in fact, that they arranged to have copies of those rings made by Sweden’s royal jeweler, at considerable expense, during their 1955 visit to Stockholm. Yourcenar later mentioned the rings in an unpublished travel journal called “Traversée sur le Bathory” about yet another trip the couple made to Copenhagen in 1964. Though several museums were closed when they arrived, “one can see the Bronze Age collections at the National Museum; we took a friendly peek at the Lurs, the garments tanned by their two-thousand-year residence in oak coffins, the Roman glass and silver, and the rings of which Grace and I wear copies made by a jeweler in Stockholm.”30 That jeweler was the renowned C. F. Carlman, and both women wore those gold rings for the rest of their lives.

The rings were fashioned to replicate Scandinavian originals dating back to the third century CE. As described by Morton Axboe, curator of Danish prehistory at the National Museum of Denmark, Yourcenar’s ring was of a type “known all over Scandinavia, but not outside, and dates to the period c. 200–300 A.D.”31 Frick’s was “of the type labelled ‘snake head’s rings,’ a group of golden arm and finger rings used in Scandinavia in the 3rd century A.D. They are characterized by stylized snake’s or bird’s heads.”32

The couple’s love of birds is well known, and birds on the rooftops of Paris played a part in their early romance. Marguerite would remember their significance two years later, in 1957, when she inscribed a new edition of Feux to her partner in celebration of their twenty years together.

The title page of the morocco-bound book contains one of Yourcenar’s Pierrot drawings, along with the usual poem. As Lonoff has observed, “books remain prominent at the base of the gibbet, and below Pierrot’s feet a new feature has been added: rooftops, with smoke coming from two chimneys. . . . Here too, the moon and stars that appear in the other four Pierrot drawings have vanished; winging birds have taken their place.”33

Happily, the couple’s schedule in Sweden had a little more breathing space for outings than it often did elsewhere. Yourcenar had been fascinated by Sweden ever since she was a child reading French translations of Swedish legends, folktales, and short stories.34 She and Frick eagerly set off to explore parts of the country they had not yet seen. They went to beautiful Bohuslän on Sweden’s rocky west coast, so much like the coast of Maine, then traveled forty miles north to see remarkable Bronze Age rock carvings of animals, ships, and fertility figures in Tanum. At Lake Vattern they “stayed quietly alone for four delightful days.”35 They also made a trip, while staying in Uppsala, to the village of Hammarby to tour the country home and garden of Carl Linnaeus, become a shrine to that precursor of modern ecology.36

But it was in the iron mining town of Kiruna that the travelers would make what Kajsa Andersson has called “the most exotic and most memorable excursion” of their 1955 stay in Scandinavia.37 Grace announced the trip, which would begin on May 27, in a postcard letter to Gladys Minear, writing emphatically at the top of the first card, “We are leaving Stockholm for the Arctic!”38 She had always loved adventure, and she was about to have one. Traveling the entire length of Sweden to the province of Lapland, she and Yourcenar arrived in Sweden’s northernmost city late that afternoon. The next day they saw Kiruna’s mines, toured a Sami village, and visited a trading post and museum. Their hosts, a Dr. and Mrs. Haraldsen and their two children, then took them, as Grace reports, “to their ‘kota’ a genuine Lapp house which was built for them some miles from Kiruna. We went the last quarter mile on skis, in deep snow, and both of us foundered, seriously. (My first experience of being stuck, sunk in snow and helpless. Very edifying.)” They were so energized by the full midnight sun after dinner with their friends that they stayed up, “very excited,” until two in the morning. This was the first taste for both women of an “extreme frontier” that would long retain its magic for them both. As Yourcenar later told Matthieu Galey, “I’ve always had a special liking for the frontier, for gateways to realms still more wild, like the Lapland region of Sweden and Norway.”39 Taking a noon train back to Stockholm the next day, they were enchanted by the “somber landscape in snow.” To remember this trip which had been so exceptional for them both, they purchased two stunning lithographs of reindeer herds by the artist Nils Nilsson Skum to take back with them to Petite Plaisance. Their only wish was that they could have had more time to spend in Lapland.40

On June 1, 1955, after nearly two years abroad, the couple left Göteborg aboard the MS Kungsholm—in plenty of time, as Natalie Barney had put it, for “Grace’s U.S.A. Xmas.”