CHAPTER 22

Home Sweet Home

1955–1957

Ah, what is more blessed than to put cares away, when the mind lays by its burden, and tired with labour of far travel we have come to our own home . . . ?

—Catullus

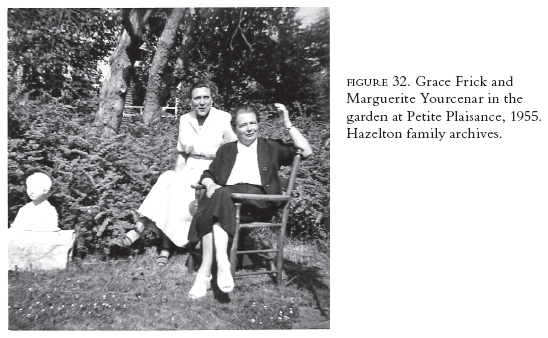

GRACE FRICK AND MARGUERITE YOURCENAR arrived back home in Maine to find that hundreds of trees had been “ruthlessly” cut to the stumps in the wooded lot behind their house.1 They mourned not only the destruction of habitat for birds and other wildlife but also the loss of a sight and sound buffer between Petite Plaisance and houses north of their property. Infuriated by the desecration, they vowed to acquire that tract of land one day. In the meantime they would concentrate on embellishing the land they already owned and refurbishing their indoor living space.

This was the beginning of a sustained period of home and yard improvement to which Frick in particular devoted her usual boundless energy. In a show of determination and style that must have raised a Northeast Harbor eyebrow or two, she often donned a pair of overalls for the purpose. (Grace once speculated that their wealthy neighbor Agnes Milliken found them neither fish nor fowl: “Apparently we fit no proper pattern of poor artist, and certainly do not fit other Northeast Harbor categories.”)2 From the “desolation” of the woodlot, she transplanted blueberries and cranberries to the grounds of Petite Plaisance. She oversaw the planting of apple trees on the west lawn and amended the soil around the Montmorency cherries to the east. She and young David Peckham struggled with a kiwi vine that would eventually grow into a leafy pergola, unique for the region, over the kitchen porch. As Yourcenar once advised the homesick young Frenchman Jean Lambert, to feel at home in America one must create, “as Grace and I have done, a domain, however small it may be, governed by fantasy or one’s personal wishes.”3

Grace, again unconcerned about Northeast Harbor mores, aired the contents of the couple’s storage trunks on the clothesline, on the grass, and on the front porch, “in full view of all comers.”4 Austin Furniture of Ellsworth installed bamboo blinds on the veranda overlooking the west lawn. George Korkmadjian brought a new Oriental carpet for the couple to try out. Bookshelves were designed, built, and stained for the studio; custom shelving was fitted to the chimney in the parlor; floorboards were scraped, sanded, and sealed.

Marguerite had fallen ill on returning to Halifax in June. Over the next several months in Northeast Harbor, Dr. Coffin made house calls for everything from phlebitis of a vein in the author’s left index finger to intercostal inflammation. Certain foods—but which ones?—brought on “bilious attacks.” One night the sculptor Malvina Hoffman and the writer Marianne Moore came for a dinner of lobster, boiled potatoes, salad, stewed plums, and cookies—and Marguerite was ill for a week.5

Throughout this time literary work, and its attendant battles, was plentiful for both women. Yourcenar’s “Reflections on the Composition of Memoirs of Hadrian,” already incorporated into the French version of the book, had to be appended to the English. Grace worked on that text during the summer of 1955. A complication of some kind arose, however, involving Frick’s old Wellesley College classmate Florence Codman. Florence had composed her own translation of Yourcenar’s original “Carnets de Notes de Mémoires d’Hadrien” two years earlier, but nothing had ever been done with it.6 Did she want it used now instead of Frick’s? Did she wish to be acknowledged in some way? She and Frick exchanged telephone calls about the matter in late July, and Yourcenar spent several days drafting a letter to Codman in August.7 On completion, the couple walked it to the post office together, often a signal that something important was happening. Whatever the difficulty was, “Autumn 1955 Florence Codman” ended up on the cumulative list of Frick and Yourcenar’s “historical affairs.” Exceptionally, the friendship among the three women survived.

After dispatching “Reflections” to the publisher, the couple started working on the English translation of the Thomas Mann essay together in late August. It proved to be something of a moving target, as Yourcenar decided to revise the French version of the article while her partner was translating it. Over the weekend of October 22–23, for example, she added three new typed pages to the text that Frick had already translated. And she still needed “to concentrate into one discussion her previous separate discussions of the Magic Mountain.”8

Almost a month later the two women did a “final” reading of the essay in English, as revised for the third time and typed for the seventh! No sooner had Yourcenar given it her stamp of approval than she decided to add another paragraph on Joseph and His Brothers. As Frick explained in the daybook, “Grace read her one-page addition that evening, but thought it insufficiently centered upon the main subject of the essay, Humanism. M.Y. admits that she had not thought of the main focus, so anxious was she to treat Joseph sequence as a whole, so agrees to rework this new addition.” Yourcenar appreciated Frick’s editorial eye. As she told a friend who had asked her to comment on his novel, “Grace Frick, to whom I am reading this letter as we sit by the fire, points out that I have offered no criticism of your book, though there are always critiques to be made (and she knows whereof she speaks, having kindly taken on the role of devil’s advocate with respect to my own).”9 It wasn’t until January 28, 1956, that an overall revision of the Mann essay, tightening the focus on humanism, was completed and translated.10 All told, there were nine or ten versions of the English translation.

Throughout all this, with the relative continuity permitted by these other projects and her tenuous health, Yourcenar was revising her 1934 collection of short stories, La Mort conduit l’attelage, which comprised the painterly titles “D’après Dürer,” “D’après Greco,” and “D’après Rembrandt.” “D’après Dürer,” whose main character was a “sixteenth-century adventurer in quest of knowledge,” would take on a life of its own and blossom into what many readers consider to be Yourcenar’s best novel. She had reached page 20 of what was still at that time a revision of “After Dürer” by June 23, 1955. Almost three more months brought her only up to page 46. About what they then began to call Le Grand Oeuvre, Grace wrote on January 29, 1956, that her companion was “feeling now well advanced and hopeful that it will be the great book that she wants it to be.” Simmering on the back burner were the poems to be published by Alexis Curvers; the translations of Constantine Cavafy, subject of another legal wrangle; a new edition of Feux; and Frick’s translation of Le Coup de grâce, which had been recently reissued in France.

Because Frick and Yourcenar had been out of the country for such a long time, the months after their return in June of 1955 brought a steady stream of visitors to Petite Plaisance, most of them for several days. In addition to Paul Minear, Jean and Roger Hazelton came in July with their son Mark. Gladys and the three Minear children arrived in August en route home from the Gaspé Peninsula. “The Emmas” from West Hartford, Emma Trebbe and Emma Evans, also came in August; they had been Grace and Marguerite’s neighbors at 549 Prospect Avenue in what now seemed another life. Ruth Hall came with her mother in October, with Florence Codman pulling up the rear in mid-January 1956. Whatever had happened regarding her translation of “Carnets de Notes,” the thank-you note she wrote to Grace after this visit makes clear that all was well between them. It also suggests from the standpoint of a sensitive third party what it was like to live on South Shore Road in winter. As Codman wrote of her departure,

At the top of the hill beyond Somesville the snow began to spread over the hills and reached across the farms along the railroad until night fell, uniting the landscape so it could not intrude into my pondering on the past four days.

They were curiously rare and intense. It was so long since we had met that time no longer counted. The empty houses at the edge of the sea isolated like a stockade in which whatever we said seemed rare and of heightened value.

I need not try to describe how I enjoyed myself. It must be enough if I once more say, Thank you.

Affectionately, Florence11

Visiting friends were an important source of pleasure for Frick and Yourcenar, but there were many others during these years of relative youth for both women, who turned fifty-two in 1955. And Marguerite’s sporadic ill health, ascribed by some to hypochondria but also quite likely related on occasion to anxiety, did not prevent her from enjoying herself on Mount Desert Island. In August of 1955 the couple discovered that horse-drawn carriage rides were available from Acadia’s Jordan Pond Stables, established in 1953, and they wasted no time signing up for them. Sometimes they took young David Peckham or houseguests along; more often they would go alone, picking blueberries in the sun along the road near the stable or stopping for tea at Jordan Pond House. Once they walked halfway around Jordan Pond and then had “two popover teas each!”12 Jordan Pond was also an ideal spot for sighting deer, whose number, age, and sex were often carefully noted in the daybook.

Mid-September 1955 brought three “heavenly” days of Indian summer, during one of which the couple sat on a nearby lawn listening to their friend Emily McKibben play Bach and Brahms on the piano. Music was one of Grace’s passions—so much so that she got caught one snowy winter’s night on her neighbor Ruth Jordan’s front porch peering through the blinds while someone played Jordan’s grand piano.13 There was no dearth of licit concert options at hand, however, ranging from a summer chamber music festival to wintertime community concerts to performances by the high school band. Grace and Marguerite patronized them all.

When the women had a rental car or could prevail upon someone to chauffeur them, they made twilight trips to Seawall or the picturesque fishing village of McKinley (today Bass Harbor) on the island’s quiet side. If the sea was fierce owing to a storm, they would drive to Thunder Hole or Otter Cliff off Ocean Drive to watch giant waves batter walls of granite. Their friend Helen Willkie was an easy mark, and she piled her four children into the family station wagon for deer-spotting rendezvous with Grace and Marguerite on many a summer’s eve.

Picnics were another favorite leisure activity during these years, whether breakfast on the shore near home or supper at the Jesuit Spring, where the women watched the sun set over Somes Sound. Clams and lobsters layered with seaweed and cooked in a great pot of salt water were a treat shared most often with the Willkies, always at the same choice spot along the ocean.

The couple continued to engage with village children, with Grace in particular always trying to open their eyes to new experiences. One summer day she was so bold as to take eighteen youngsters on the early boat to Manset for a two-hour session of square dancing.14 Several adults who were children in the 1950s recall being taken by the women on boat trips to outlying islands for picnics. “The Madame” they recall as always smiling, whereas Miss Frick, their employer, was more strict. Richard M. Savage II, who still lives in Northeast Harbor and runs a charter boat service, vividly remembers these picnics. Frick and Yourcenar brought food “in big baskets, and there was always cheese and bread. And wine, for sure, though not for the kids. Sandwiches, but not American-type sandwiches. No bologna and cheese and tuna fish. There were cheeses and nice meats, and you ate it European style.”15

On the night of the women’s first Halloween in Northeast after their two years in Europe, Marguerite dressed up as a ghost and Grace donned a witch’s hat and black robe to receive trick-or-treaters. As the years went by, in part no doubt because people did not know quite what to make of Frick and Yourcenar’s household, village children were hesitant to trick-or-treat there in small numbers. Instead, eight or ten children would arrive en masse. They then went into the parlor to earn their treat by telling a ghost story, reciting a poem, or correctly answering a question related to what they were learning in school!

In the summer of 1956, attempting this time to get youngsters to engage in one of her own favorite pastimes, Frick launched a children’s garden contest. On the morning of June 7—“Marguerite’s birthday”!—she made the rounds of Northeast Harbor’s schools to announce the competition and its handsome twenty-five-dollar first prize.16 Miss Elizabeth Tilton of Sargeant Drive, a summer resident and garden lover, was recruited to serve as a judge. Rick Savage won first prize over five other competitors for a vegetable garden that his mother constantly pestered him to weed. But genetics may have helped him score that win: his uncle was the landscape artist Charles K. Savage, who created the extraordinary Asticou Azalea Garden.

The years after Memoirs of Hadrian came out were a time of high-energy, prolific literary output and mutual engagement for Yourcenar and Frick in multiple spheres of activity. On the domestic front, late 1955 brought an event long awaited by both women: a new addition to their family. On December 15 a five-month-old black cocker spaniel came into their lives, the most splendid Christmas present either woman could imagine. Both of them had been dog lovers since childhood. Grace was especially fond of cocker spaniels, having had one back in Kansas City, and Marguerite considered the breed to be just the right size for their house. They had had an eye out for a puppy as far back as 1950. During Yourcenar’s spring break that year, the couple spent a few days in the White Mountain region of New Hampshire where they visited Dupont Kennels. They found “thirteen perfect cocker spaniels” there, five of them new puppies. Frick described them at the time as “the most affectionate beings ever seen.” Perhaps knowing whom they needed to impress, the puppies “kissed and licked Marguerite from head to toe.”17

A lot of thought went into choosing a name for the new creature. Several possibilities were suggested by the dog’s scampish nature or his jet-black coat: Sprite, Devil, Imp, Scaramouche, Smokey, Blackball, and Booker T. Washington (!). Food was another prominent theme: Molasses, Popover, Muffin, Plum Pudding. In the end they settled on Monsieur Popover, which eventually got shortened to Monsieur.

Monsieur Popover’s mistresses tracked his progress like proud parents. On January 4, 1956, “puppy” mastered the descent of the precipitous main stairway, “squealing with fright as he goes.” Grace loved regaling her young nieces, Katharine and Pamela, with accounts of his adventures and showing the girls what a lively household Petite Plaisance could be:

It happened like this. We have two staircases, even though this is a very little house. The backstairs are so steep that some sea-captain who once lived here made himself a handrail along the wall to hoist himself up after he got around the turn. Whoever built the back stairs, and that was over a hundred years ago, did not wish to saw and plane any more boards than they absolutely had to just to go up from the kitchen, so they made as few steps as they dared, with an extra high one at the top and bottom. So it is very hard to begin the climb, even for two-legged creatures, and still harder to finish. All the little children of the village have been here at one time and another when their fathers were doing our painting or carpentering after we moved in, and the smallest tots were always the ones who loved most to go up the back stairs, hanging tight to the rope, then running through Marguerite’s bedroom to the hall, and down the front stairs, sliding one hand down the banister rail. So of course this little dog would love to do just what they do.18

Impishness was a trait that Grace shared with her new cocker, as people who knew her often comment. Deirdre “Dee Dee” Wilson, who grew close to Grace in the 1970s, calls her “really mischievous, elf-like.”19 Robert Lalonde’s fictionalized account of Yourcenar’s 1957 lecture tour in Canada exaggerates Grace’s devilish tendencies to the point of comic caricature.20 Dr. Kaighn Smith, now a year-round resident of South Shore Road, asked me once—half in jest?—if I knew that Grace Frick was a witch. He will never forget the sight of her, all alone some distance down a wooded lane, dancing a spry jig in her long black cape on the night of an early first snow.21

One of Frick’s most renowned pranks was visited on the former host and hostess of her graduate residence at Yale University, Paul and Gladys Minear. When Paul Minear became Winkley Professor of Biblical Theology at Yale Divinity School, Frick was determined to congratulate her friend in a manner equal to his accomplishment and symbolic of their shared Yale connection. In February of 1956 she wrote,

I could think of only one fitting token to send, but it was easier thought of than procured. Over the holiday yesterday, however, I had a chance to place the small order with a local man on a visit home from Boston, and you should soon receive my congratulations in the form, if not the color, that I desire. The color should be yellow, . . . but maybe the order will come in green. Let me know, please, if you receive anything soon of those two salient possibilities.22

Harking back to the days when Grace partook often of the Minears’ bananas at 158 Whitney Avenue, the gift arrived shortly; shipped from Boston’s wholesale market, it was an eighty-pound stem of tiered bananas.

Hall Willkie, who spent lots of time with Frick and Yourcenar as a youngster, remembers Grace’s playful, “childlike way”: “She was so much fun to just take a walk with. Things she would point out, things she would see, and I think that’s why children loved her so much, because she was not an old fuddy-duddy. She was fun and curious and mischievous, and she enjoyed intrigue a little bit.” Like other young familiars of Petite Plaisance, Willkie felt closer to Frick than to Yourcenar: “I think Madame Yourcenar enjoyed us, too, but she kept us at a bit of a distance. She loved teaching us things like how to bake bread, and we would have meals together a lot, but Grace Frick would just embrace us completely.” Willkie also notes how different the women were from their neighbors:

No one really knew who they were. The local people were a little suspicious of them because they walked around in black capes. I can still see them as a little boy, and people just didn’t look like that! So very odd or off-beat. And the summer people, mostly rather privileged, certainly had no understanding of them. I learned later in life that there was a lot of talk about their relationship, and people weren’t happy about that at all. The lesbian relationship was suspected. I remember as a boy, people threw eggs at their door once. Things like that. People would say, “You know, those women . . .”23

Frick and Yourcenar eventually became so attached to the Willkie children, Frederick, Arlinda, Julia, and Hall, that they decided to leave them their home as a life estate. In a sense, like David Peckham, they fulfilled the couple’s wish, forsaken along the way, to adopt a child of their own. Helen Willkie, mother of the brood, had come to know the women quite by chance. She and the children summered in Seal Harbor, just up the coast from Northeast, for a number of years in the 1950s and early 1960s. The housekeeper at their cottage was Bernice “Bunny” Pierce. One day Pierce noticed a copy of Hadrian on Helen’s bedside table. As Hall Willkie reported, “Bunny told my mother, ‘I know the person who wrote that book. Yes, I help take care of them, and she’s a friend.’ So Bunny introduced them, and they became fast friends.”24 Adding to the serendipity, Helen’s brother-in-law was the antiracist presidential candidate for whom Frick had campaigned in 1940, Wendell Willkie.

When I phoned Julia Willkie in Manhattan one day to ask what she remembered of Frick, I was astonished to hear that she had a framed picture of Grace in her bedroom. “I adored that woman!” Julia exclaimed, adding,

She taught us how to make French bread, how to tell what stars were what. I tell you, we were always at their house. I can remember sitting on their porch and snapping green beans. That kitchen was magical, with all those various jars. To me, Grace Frick was just . . . a life force! She may have been a little bossy or opinionated or whatever, but she was a wonder! I was always crazy about her. I mean, I always liked Madame Yourcenar, but . . . Well, of course she was a scholar and a writer. She was colder and more standoffish. Grace to me was kind of, I don’t know what you’d call it, Yankee backbone or something, but she was a love. And she would say things like “You need to take a nap.” And you did!25

Questioned about the dynamics of Frick and Yourcenar’s relationship, Julia paused for a moment before answering, “I was fairly young, but I would say Miss Frick held it all together. I would say that she allowed Madame to call the big cards. I don’t think that Madame would have had the wonderful life she had if it hadn’t been Grace Frick who arranged for the world to keep going so that she had the time and the luxury to do her own work.”26

The next long trip to Europe was to take place in the fall of 1956. Yourcenar had agreed to some lectures in Holland and Belgium. Afterward she and Frick would spend a few weeks in Paris before heading to the south of France, where they had reserved a small house for the winter.27 The plan was to make that location in Villefranche their base of operations for trips to Italy, Spain, and possibly the Levant. As in 1953, Grace made a weeklong trip to Kansas City before they set sail. On September 25 she met Marguerite, who had traveled from Maine with Monsieur Popover, at Grand Central Station. From the start the omens for this trip were less than auspicious, with Marguerite receiving weekly “hepatitis vitamin” shots and taking liver pills.

Yourcenar had prepared several talks: “Books and Ourselves,” “The Writer in the Face of History,” “Europe and the Notion of Humanism,” and “Greek Statues.”28 On October 12, in the Dutch city of Arnhem, she was all set to deliver “Books and Ourselves” when Frick discovered that “The Writer in the Face of History” was the advertised title for that venue. Dashing back to the hotel for the right notes, Grace made it back to the lecture hall just in time for the talk to begin without anyone being the wiser. The real face of history was soon to show itself, however.

On November 2 Frick began noting disturbing events in the daybook: “Israel takes Gaza. French and English bomb Port Said, obliterating Egyptian air force.” Two days later she recorded in telegraphic haste, “News from Hungary very bad. Russians re-enter Budapest. Mass slaughter. Decided (M.Y. after little sleep) to return on first boat to U.S.A. because of conditions Suez and Hungary.”29

Yourcenar, for her part, was revolted by the arrant aggression of everyone involved in these events, and by the belligerence of the British and the French in particular. She wasn’t even sure that she wanted to return to France anytime soon. As she wrote to a friend in 1957, “Paris was abhorrent last year, at the time of the Suez crisis, like anyplace where madness, illusion, and willful confusion hold sway, along with deceit. I left there devastated. It seems that the alarm clock is set for the hour of disaster, and we can hear the minutes ticking by in the night.”30 To a sorely disappointed Natalie Barney, she wrote, “During that dark month of November, it seemed that fury, spite, and violence were everywhere.”31

Josyane Savigneau has used a sentence from that letter to Barney as proof of an ongoing struggle between Yourcenar and Frick over European travel: “The further we go along, the more we note the wisdom of the resolution that brought us back here, and this despite regret at not seeing our friends from France at greater length or more frequently.” According to Savigneau, Yourcenar laid down the law regarding how much America she was willing to put up with:

There is the proof, for those who might have doubts about the subject, that debate had indeed existed. But relocating in Europe would have been unacceptable for Frick. Where else but in an English-speaking country would she have found the one compensation for her self-effacement, the indispensable feeling of being absolutely necessary to Yourcenar’s survival?

. . . The compromise had perhaps been imparted to Frick couched in one of those apparently innocuous sentences that Yourcenar was so good at devising. The deceptive insignificance of those sentences was contradicted by a tone that revealed long-nurtured decisions, admitting not the slightest discussion: “We’re returning to Petite Plaisance, but we’ll travel.”32

Yourcenar was indeed master of the pithy remark, but Grace had been a travel lover long before she met Marguerite, and there is no indication that she pled the case to go home in 1956. In fact, she was disappointed that their hasty departure meant abandoning trips to Aix-la-Chapelle, medieval Bouillon, and Arlon’s archaeological museum.33 The fact of the matter is that although the two women made five more trips to Europe over the next fifteen years, and did a great deal of traveling within the United States, they did not go back to France again until the spring of 1968. I strongly suspect that this was one of those times when Frick let Yourcenar “call the big cards.”

Which is not to say that she was unhappy to find herself home for the holidays. The nearly monthlong series of winter festivities at Petite Plaisance got into full swing on December 13, Saint Lucy’s Day. Shirley McGarr, Grace and Marguerite’s near neighbor, recalls that the couple “joyously celebrated every holiday.”34 They decorated the main entrance to the house with a traditional Maine Christmas wreath, hung a sheaf of evergreens on the back door, and draped garlands of balsam or pine over both entryways. Grace also initiated a holiday tradition of her own devising. Marguerite once described it to Paul and Gladys Minear (in her original English): “We are snow-bound here, but very comfortable inside the house. Grace always puts dozens of gold, blue and red glass balls on our apple and cherry trees, so we look like having a magic orchard at Christmas.”35 When Marguerite was a child, her father would hang oranges on the branches of trees for her to pick at their villa in the south of France.36 Whether Grace’s colorful balls owe anything to that fond memory we don’t know, but Petite Plaisance carries on the Christmas tradition of the “magic orchard” to this day.

Saint Lucy’s Day is a primarily Scandinavian holiday that Grace and Marguerite first experienced in Stockholm in 1953.37 They began celebrating it in Northeast Harbor in 1956. The two women had not had a tranquil Christmas at home for five years.38 In the interim they had made two long visits to Sweden and grown deeply attached to that country and its culture. Yourcenar often said in interviews that she had “a passion for Sweden.”39 In 1962, speaking for herself and Frick, she called Scandinavia one of their favorite places.40 Honoring Saint Lucy’s Day was a way to bring a beloved part of the world home with them.

That first celebration was a simple and intimate one. Marguerite made Swedish pastries the night before, a variation on the traditional lussekatt. Grace woke up the next morning, before sunrise, to the strains of her companion playing Mozart Variations on the spinet piano in the living room downstairs. Moments later, in the dark of dawn, Marguerite and Monsieur climbed the stairs to Grace’s bedroom with a tray of hot coffee, the special buns, and a burning candle. As Grace noted years later, Marguerite would faithfully re-enact this ritual every December.41

Josyane Savigneau has emphasized the connection between Saint Lucy’s Day, a date often underlined in Frick’s daybooks, and Yourcenar’s beautiful Greek friend Lucy Kyriakos.42 If there was ever any truth to that interpretation, Grace did not let it stop her from entering wholeheartedly into the spirit of the holiday. Over time, in addition to the couple’s private custom, Saint Lucy’s Day became a yearly event that they shared with friends and neighbors.

Shirley McGarr remembered the Saint Lucy’s Day gathering: “Oh, Miss Frick! . . . I can see her coming down the stairs with the crown on her head, complete with lit candles, and dressed in a flowing white robe—very Swedish, or very Scandinavian.”43 The traditional ritual features a young girl dressed all in white; on her head she wears a crown of evergreens that holds several glowing candles. In Swedish homes the eldest daughter often donned the festive headdress and woke her sleeping father with sweet cakes and singing. At Petite Plaisance, Grace took the daughter’s part, mounting the steep stairway of the house in a floor-length white garment, crown and candles on her head, and waking Marguerite in the traditional way. She then made her dramatic return to the first floor, leading revelers into the parlor where Scandinavian pastries, cakes, coffee breads, and hot beverages awaited them.44

In 1956 the time between Saint Lucy’s Day and Christmas was largely taken up by letters and telegrams related to the “Curvers affair,” the latest in a long line of battles with publishers who were viewed as having failed to honor their obligations to Marguerite Yourcenar or her work. Alexis Curvers had published Yourcenar’s poetry collection Les Charités d’Alcippe without letting the author proofread the galleys. Predictably, the forty-page chapbook contained a variety of errors. Curvers was incensed when he found out that Yourcenar was hand-correcting the errors in every copy of the book she signed. Lawyers were consulted on both sides, and relations grew increasingly strained. On December 19 the tension was ratcheted up a few notches when Yourcenar received in the mail the copy of Les Charités, furiously torn in two, that she had personally inscribed to Curvers and his wife. December 21 was so thoroughly consumed by work on the conflict with Curvers that Yourcenar and Frick were up all night writing, correcting, typing, and retyping letters related to this indignity. At first light the next morning, instead of collapsing, exhausted, into bed, the two women walked down to Clarks’ shore, opposite Petite Plaisance, to greet the dawn, “enjoying the purity and clarity of the air, the waning moon and the first red in the east before coming back for two hours’ sleep.”45

On Christmas Eve the couple attended a midnight worship service at the Somesville Union Meeting House, a Congregational church located near the cabin they had rented during their first summers on Mount Desert Island.46 Christmas Day itself was marked, as it would continue to be over the years, with a traditional turkey dinner. One touching relic of Christmas in the 1970s, saved by Marguerite, suggests that the women affectionately pressed their canine companions into service as intermediaries for gift giving. It is a typical rectangular gift tag, with a red string attached to one end, bearing colorful images of Christmas bells. Beneath the printed words “Joyous Noël,” Grace had written in French, “To my dear, dear Maîtresse d’Hôtel from Zoe.” With “Maîtresse d’Hôtel” apparently a feminized form of maître d’, Zoé’s gift was undoubtedly intended for the person in charge of serving her meals. Zoé obviously understood that Christmas involved giving and receiving gifts, however; on the back side of the tag appeared the following appeal: “I would like you to have a color portrait made of me.”47

New Year’s Eve 1956 was cold and clear. When the pendulum clock on the living room mantel struck midnight, Grace, Marguerite, and a friend named Roger Williams rang in the new year with a glass of Grace’s famously spiked eggnog. Despite the frigid cold, in a throwback to ancient Greek celebrations of Dionysus, Lord of the Vine, Marguerite and Grace poured wine onto the ground from the veranda on the west side of Petite Plaisance, as Monsieur, eager to join the festivities, tried to lap it off the snow.48 The next morning found the two women breakfasting in bed and reading aloud “The Wrath of Achilles” from the English translation of The Iliad. Perhaps they were looking to antiquity for inspiration in their ongoing battle with Alexis Curvers—which, of course, they eventually won.

The round of winter holidays came to an end on January 6 with the Feast of Epiphany, the last of the Twelve Days of Christmas. The customs surrounding the holiday vary by country, but special sweets and pastries are almost always center stage. At Petite Plaisance, 1957 saw the first of many gatherings for galette des Rois, or kings’ cake, which Grace and Marguerite viewed as an appetizing way to acquaint young people with a French tradition. That first year the new French teacher at Mount Desert Island High School, Mr. Noe, brought his classes to Petite Plaisance for kings’ cake and hot spiced cider. Later gatherings would include children from Northeast Harbor’s Union Church as well as local students and neighbors. One year Yourcenar baked an Italian panettone for Epiphany. In 1969, when she and Grace were visiting Aix-en-Provence, they bought a bakery galette and had it for breakfast in their hotel room. One way or another, they never failed to observe that special day.49