CHAPTER 25

Travels and Travails Foreign and Domestic

1960–1962

The magnificent Mississippi, rolling its mile-wide tide along, shining in the sun.

—Mark Twain

THOUGH MARGUERITE HAD A BAD cold, she and Grace spent several consecutive late nights enjoying fado music in Lisbon’s smoky bars. After midnight mass on New Year’s Eve at the Estrela Basilica, the pair were mesmerized for hours by the plaintive strains of Herminia Silva at Bairro Alto. Once Yourcenar had recovered from these overindulgences, she and Frick visited a few other parts of Portugal: Tomar, Batalha, Aljubarrota, and Óbidos.1 Their trips often had a literary purpose. One important destination was the centuries-old pilgrimage site of Santiago de Compostela, to which the character Zeno would be headed at the opening of L’Œuvre au Noir.

This tour of the Iberian Peninsula was very much like the couple’s 1958 trip to Italy: carriage rides, social encounters (notably, with Isabel García Lorca, sister of the assassinated antifascist poet Federico), Roman ruins, long walks, and museums. Yourcenar gave at least six lectures in Portugal and Spain, the latter being where the women moved their base of operations in late March. In Madrid they made five long visits to the Prado, where they were particularly struck by the early Flemish paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, the Master of Flémalle, Hans Memling, Joachim Patinir, Rogier van der Weyden, and Jan van Eyck.2 They were fascinated in April by the events and processions of Holy Week in Seville. On May 11 they sailed for home.

Awaiting them in Northeast Harbor was Natalie Barney’s Souvenirs indiscrets, whose author would be eagerly anticipating commentary from her friends. Yourcenar read the book aloud to Frick in front of the fire. On June 5 she wrote Barney a long and laudatory letter congratulating her friend on her tact, gentle humor, and perceptiveness regarding those she knew and loved. Alluding to their early discussions of Henry James, Yourcenar playfully imagines the young woman Natalie was when she first saw Belle Époque Paris as “a younger, less chaste sister of Daisy Miller and Isabelle Archer tossed into the Parisian labyrinth of love and society life.” In closing, she called their recent European trip “enormously enriching despite an almost constantly rainy winter, even on Madeira, and a case of bronchitis that now seems to be for me a sort of inevitable tribute to the winter months. Here we are back home, I to work on a book, Grace to translate, and both of us to cultivate our garden.”3

Cultivating their garden was something Frick and Yourcenar took seriously. They were already composting and gardening organically in the 1950s, long before the practice became fashionable. In 1960 they nearly doubled the size of their property, and began to develop a woodland garden, when they finally succeeded in acquiring the lot behind Petite Plaisance.4 Barney later sent them a one-thousand-dollar gift—a sort of inheritance before the fact—and they decided to credit her with purchasing the coveted half acre. Frick’s thank-you letter suggests how much the parcel meant to her companion:

Marguerite had set her heart on having it after she saw the slashing of the trees there which occurred during one of our absences, and since we have owned it, she has worked between stretches at her desk to cut paths through the brambles and to clear the brush while leaving havens for the birds and ample space for the return of the native ferns, blueberries, and white-flowering bunchberry which grows so low to the ground, as you may remember. Although her health is much better than when we first came up here, she does not take the long walks or climbs for which the Island is best known, so it is of real importance to her to have this bit of wildland so accessible to her, and her own, to do as she wishes with it.5

On returning from Europe, it never took the women long to get back into the swing of island life. Summer 1960 brought many get-togethers and outings with friends, among them the Willkies; Agnes Milliken; Mrs. Belmont; Alf Pasquale and Chuck Curtis; Erika Vollger; Elliot and Shirley McGarr; Hortense and Wyncie King; the orchestra conductor Max Rudolf and his wife, Liese; Gertrude Fay, just back from Ireland; Bob and Mary Louise Garrity, at whose lodge on Indian Point Grace and Marguerite enjoyed going for a swim; and various young people who stayed over at Petite Plaisance after dances at the Kimball House a few doors up the street.

Ledlie Dinsmore and her brother Clem, who summered with their family on Greening Island near the mouth of Somes Sound, were among the latter youth. Grace and Marguerite had known their great-great-aunt Henrietta Gardiner, a passionate promoter of social causes, since the 1940s. Always eager to befriend young people, they were happy to help out. Whenever Ledlie and Clem could not row home in pea-soup fog, they spent the night in the guest rooms of Petite Plaisance.

In early September 1960 Grace, who had recently been scaling cliffs in Portugal, fell down the steep stairway at Petite Plaisance in the middle of the night, breaking her left shoulder blade and a bone in her left hand.6 Almost immediately she began having severe intercostal nerve irritation on the injured side of her body, “much like the pain M.Y. feels above the heart region.”7 By September 20 she had also contracted shingles in her mouth and jaw.

Two changes in the content of the daybooks may relate to her health and state of mind. One involves the level of detail provided by those yearly agendas, which begins an overall decline in 1960.8 The other concerns a few sharp comments Frick made that October, while she was still receiving treatment for injuries related to her fall. On Sunday, October 30, for example, the women hosted a party for twenty junior high schoolers who were collecting donations for the United Nations Children’s Fund. On Halloween the next day Grace wrote irritably, “Ten or twelve smaller children in cheap, foolish costumes came to door. Three repeaters from Sunday were refused as too old for trick or treat.” She and Yourcenar hated waste of any kind—and commercially manufactured Halloween costumes would have fit that bill for them both—but Frick loved children, and remarks like that were not typical for her.

Both women were back in high spirits by Christmastime, however, when what Grace called “a bodyguard of ten little boys” paid them a visit with a long-eared friend. Yourcenar described the event at the end of a letter to Jacques Kayaloff, with whom she had spoken by telephone on December 26:

I’m sorry if I may have seemed a bit distracted during our phone conversation last Monday. . . . But nine or ten boys from the village had just come clattering up to our door with a very charming gray donkey named Ebenezer. He was all decked out in ribbons, and hung around his neck was a letter for us (to thank us for sending him a barrel of carrots for Christmas). Monsieur and a dog belonging to one of the boys were barking to their hearts’ content. We were serving treats. The donkey was eating peanuts, shells and all. The children were munching on candy. So you can see how hard it would have been, perhaps even unwise, to abandon our guests even for a moment.9

Nineteen sixty-one would be a year of American travel and lecturing during which Yourcenar would receive her first honorary doctorate. Grace Frick’s friend Charles Hill had been trying for quite some time to get Smith College, in Northampton, Massachusetts, to bring her to campus as a speaker.10 Hill had served in various capacities at Smith, including dean of the faculty, assistant to the president, and chairman of the English department. André Gide’s former son-in-law, Jean Lambert, whom Yourcenar had known for several years, was also teaching at Smith, and Ledlie Dinsmore was a sophomore there that year.

Yourcenar gave three lectures at Smith: “Hellenic History as Seen by the Poets,” “Functions and Responsibilities of the Novelist,” and “Marcel Proust.”11 Frick and Yourcenar also made a point of seeing Ledlie several times while they were in Northampton. Ledlie eventually moved into Dawes House, Smith’s Maison Française.

The most interesting aspect of Frick and Yourcenar’s time at Smith may, however, have been what was going on in the background while they were there—namely, as Charles and Ruth Hill called it, the Dorius Affair. It had been only a few months since an infamous McCarthyist scandal had erupted in Northampton involving Newton Arvin, a respected scholar of American literature who had taught at Smith for nearly forty years. Arvin had won the National Book Award for nonfiction and published widely admired biographies of Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. On September 2, 1960, he was arrested for obtaining through the mail what was deemed homosexual pornography: photographs of male models that an article years later in the New York Times likened to Calvin Klein underwear ads.12 To add insult to injury, Arvin was a member of the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners. He was also a close friend of Truman Capote.13

Arvin was found guilty of possessing obscene materials, sentenced to a year in jail, and fined twelve hundred dollars. His jail sentence was suspended, apparently in exchange for the names of two Smith colleagues who also collected pornography.14 One of them was Joel Dorius, who had taught Elizabethan drama at Yale University for nine years before coming to Smith. Among the offensive materials in his possession were photographs of Etruscan wall paintings.15

Unlike Newton Arvin, Dorius did not have tenure at Smith and, along with Edward Spofford, he was fired before a verdict on his case was even rendered in court. While Yourcenar and Frick were in Northampton, Smith’s trustees were holding heated special sessions related to these two faculty members in which Charles Hill was an active participant. Hill held Dorius’s work in high regard, characterizing him to his visiting friends as “a Shakespeare scholar of marked ability.”16 Both he and Ruth felt strongly that Dorius should be reinstated by the school. He would tell Grace in a letter written the day after her departure how much he regretted “the interruptions and tensions which ‘L’Affaire Dorius’ brought into my existence during your sojourn.” At the end of that same letter, he lamented, “Incidentally, our trustees reached a decision which hasn’t been announced. I’m afraid I fear the worst.”17 Both Dorius and Spofford were permanently sacked.

I initially wondered if it might have been more than mere coincidence that Yourcenar and Frick, for the first time in their more than two decades together, were lodged in separate quarters during their three nights at Smith. But that unusual fact turns out to have been caused by discrimination of another sort: Frick stayed with Ruth and Charles Hill because the Maison Française, which hosted Yourcenar, did not allow dogs.18

In 1963 the Massachusetts Supreme Court overturned the obscenity verdicts against Arvin, Dorius, and Spofford. Smith acknowledged in 2002 that all three professors were wrongfully terminated and created a fund for the study of civil liberties, a lecture series, and an annual American studies stipend in their names.19 When Yourcenar and Frick returned to Northampton in June of 1961 for Yourcenar’s honorary doctorate, the author stayed at the home of Smith’s president Thomas Mendenhall, and Frick bunked again with Ruth and Charles Hill.20 Just around the corner from the Hills’ residence on Crescent Street, two stately old homes stood side by side that would soon be taken over by Smith to serve as dormitories. They would be named after the renowned medievalist Eleanor Duckett and her novelist companion Mary Ellen Chase, who were a professorial force to be reckoned with at Smith for forty years. In subtle homage to the lifelong companions, Duckett House and Chase House were architecturally united in 1973.21

Yourcenar’s talks at Smith College were just the beginning of a long tour during which the author gave lectures in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Kentucky. Subjects included “Christian Thought in French Literature,” “The Universe of Proust,” and “Attitudes toward War in French Literature.” On March 25 Frick left Yourcenar and Monsieur at Louisville’s Watterson Hotel and departed for a week in Kansas City. On March 29 a Dr. McDonnell in that city informed her that two nodules in her right armpit must be “promptly” excised. But the only thing Grace did promptly was return to Marguerite in Louisville, where the two would board the Delta Queen on April 2 for a trip down the Mississippi River.

The weather was very fine that day, and when the boat stopped in Paducah, Kentucky, the women got off to see the hardware store where Uncle George LaRue had been working when he married Aunt Dolly. In Memphis and again in Natchez the azaleas were in bloom, and the couple were treated to the sight and song of the mockingbird. In New Orleans they explored the French Quarter and caught a show at the fabled Club My-O-My, known despite laws against female impersonation for “the world’s most beautiful boys in female attire.”22 It was the place to be in mid-twentieth-century New Orleans for both locals and tourists. A highlight of the rest of their stay was Audubon Park, with its hundreds of wading birds. By the time they got off the Delta Queen in Cincinnati on April 21, they had spent almost three weeks on the Mississippi or exploring ports of call along its banks.

The river cruise made a lasting impression on both women. Years later Yourcenar would remember it in the preface to Blues et gospels:

It was slow and beautiful. In the evening we would sometimes moor at the edge of small, half-submerged islands haunted by the songs of birds. The crew and the staff were black and, in our regard, full of the kindness particular to people of color as soon as they sense sympathy rather than condescension. We were invited to the evening religious service on the little rear deck that was reserved for them. The river flowed in waves, sometimes rapid, sometimes sluggish and murky, reddened by the setting sun. “Deep river, dark river.” Those warm voices, whose cracks and discordances I was just beginning to get used to, seemed to arise from the depths of a temperament, of a race, at once present and past.23

During this descent into the South, both women found themselves face-to-face with what Yourcenar would later call “the misery of the Blacks and their fight for integration.”24 As the 1960s unfolded, that fight became increasingly important to them.

Finally, on April 26, almost a month after Dr. McDonnell found two suspicious lumps on her chest, Frick was hospitalized in Bar Harbor to be operated on, as in 1958, by Dr. Silas Coffin. Amazingly, Monsieur went to the veterinary clinic the same day to have two warts removed. Dr. Coffin used a local anesthetic. Dr. Cameron, the veterinarian, put Monsieur lightly under and flushed the channels of his ears. Frick’s nodules were duly removed, and she was kind enough to mention in the daybook, despite giving more detail about the dog than herself, that the pathology report came back clean. There was no malignancy.

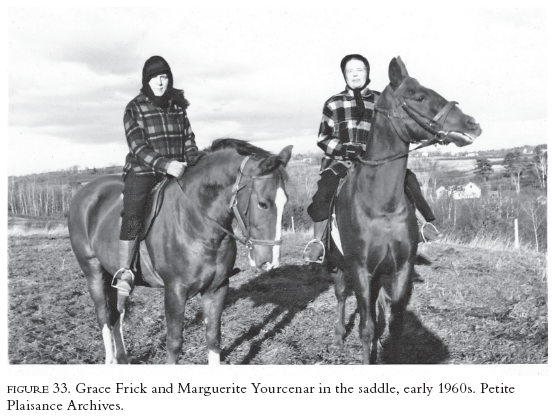

In the late summer of 1961 Marguerite momentously decided to join Grace in one of her favorite pursuits, horseback riding. On the afternoon of August 30 Marguerite had a brief lesson at the same Jordan Pond stable from which she and Grace regularly took carriage rides in Acadia Park. Under the tutelage of a fifteen-year-old instructor named Lynn Ahlblad, a horse lover whose family ran a shop in Bar Harbor, Yourcenar rode Dallas that first day. Not everyone was convinced that she was cut out to be a rider. As her friend Shirley McGarr once said,

I’ve told you what a marvelous horsewoman Grace was, just wonderful. And of course Madame Yourcenar couldn’t care less about that, that was not in her world. But she did it to be with Grace. . . . Grace looked great on a horse ’cause she was tall and angular, but Madame Yourcenar was just plunked there, you know? And I’m not meaning that in a derogatory sense. That’s the way her body was built. She was not built for a horsewoman. But she did it, and she’d sit there and she’d kind of grin, you know, that grin she had . . . But she would do things that Grace . . . that meant a lot to her.25

Lynn Ahlblad remembers the experience vividly—and well she should, since Frick had invented “the scheme” of having the poor girl teach Yourcenar how to ride in French! Ahlblad speaks of “Madame” wearing the same beatific smile that Shirley McGarr mentions in describing her horseback riding efforts. She also recalls that both women, who of course invited her to Sunday tea, were “very interested in kids, and very generous and gracious.” Chuckling at the memory, Ahlblad adds, “Sometimes Grace could be a little overbearing, but, you know, it’s always nice when children have that connection with brilliance.”26

Yourcenar continued to take lessons that fall and eventually caught the riding bug. It’s not hard to imagine, given how much she loved horses, with her and Grace never missing a chance to visit ones they knew around the island. By mid-October Frick was driving Yourcenar to Bangor for more advanced lessons with Alejandro Solorzano at the Forward Seat School of Horsemanship. Altogether, before winter set in, Yourcenar took ten lessons with that former member of the Brazilian Olympic team.27

It cannot have been easy for someone with Yourcenar’s sense of personal dignity—to say nothing of her stature as a writer—to attempt a pursuit that, while second nature to her partner, was not at all natural for her. Yourcenar did not have the build of an equestrian. Nor had she ever been an athlete. Her general health, moreover, was not vigorous. Yet it is clear from all reports that, knowing how much it meant to Frick, she gave herself over to riding with humility and grace. For her trouble, as she wrote a few years later, she would gain “one of the most profoundly lived parts of my life.”28

In the space allotted to January 1, 1962, at the end of the 1961 daybook Grace made a note to herself: “Apply for new passports.” She and Marguerite had decided, contrary to their usual practice, to take a monthlong cruise to their beloved Scandinavia that also included stops in Iceland and, most intriguingly, the Soviet Union. After spending a night with the Minears in New Haven, they would board the SS Argentina in New York City on June 11. The cruise was so thoroughly packed with activities—one is tempted to say antics, judging from the photographic memorabilia—that Grace merely listed them in the daybook. But they did see some spectacular fjords and waterfalls along the way in this season of the midnight sun.

Yourcenar later wrote about the trip to her Italian translator, Lidia Storoni Mazzolani: “This year we contented ourselves with a cruise to Scandinavia; it was the first time we took a chance on this mode of transport, which is hardly made for serious travelers. I’m quite sure that it will be a one-time experience; nonetheless, it provided us a few admirable days along the coast of Norway and Iceland, and the pleasure of spending a few days once again in two cities that are very dear to us, Copenhagen and, especially, Stockholm.”29

What intrigued Frick and Yourcenar about this particular cruise was the possibility of spending three days in Leningrad. They viewed it as a chance to get a sense of the new Russia before deciding whether to make a longer journey there. Yourcenar’s letter to Mazzolani, written shortly after the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, attracted a lot of attention when it was published after her death—she forbade it to appear during her lifetime—because of its extremely frank assessment of the USSR. Her and Frick’s short stay in Leningrad, said Yourcenar,

had an effect on me (and also on Grace) that I had not anticipated; all in all, as far as I’m concerned, it was one of immense discouragement. What had I hoped to find? I certainly had not counted on a glimpse of Eldorado. But, reacting no doubt against America’s stupid anticommunist propaganda, with its infantile clichés, no doubt I believed I would at least encounter a newer world, perhaps a more “vital” one, even if that world were hostile or foreign to us. What I found, from the moment at dawn on the first day when we caught sight of the Russian officials boarding the boat in the fog until the sleepless night of the third day . . . was quite simply the Russia of Custine, that eternal mixture of bureaucratic routine, suspiciousness of strangers, an already Oriental nonchalance, and prudent mistrust; and that inert and almost suffocating sadness that so often appears in Russian novels, which I did not expect to find there still.30

Not surprisingly, she and Frick decided not to return to the Soviet Union.