CHAPTER 31

Round Two

1971–1973

So long as he lives a guest should never forget a host who has shown him kindness.

—Homer

UNLIKE GRACE FRICK, MARGUERITE YOURCENAR did not revel in Maine’s hard winters. She did go so far as to say she didn’t mind them once, it being “difficult to find a good climate in the winter. Paris is beastly, also.”1 But both women gloried in the beauty of autumn, with its brilliant blue skies, trees ablaze with color, and luxurious warmth of Indian summer. On just such a day in October of 1971 Marguerite took Valentine Lady to pick the last flowers of the season along a South Shore Road blissfully devoid of summer traffic. Overjoyed, Valentine darted down a leaf-strewn path, “her little paws sturdy on the golden foliage.” Heading toward the sea, the cocker disappeared in the bushes of a neighbor’s garden. Marguerite called out to her gaily, taking pleasure in the sound of her name. Instead of bounding toward her mistress, Valentine ran toward the road. “Through the bushes,” Yourcenar recalled,

I vaguely watched a car to my left moving down the street at a very leisurely pace. A second later, a voice called out to me, “Is it your dog that I have hit?” I took a few steps back, toward the road—Valentine was stretched out on the ground, dead. She must have thrown herself against the car and bounced off like a ball. There she lay, her neck broken. I had the very strong feeling that vibrations of life were pulsing from her still warm body and disappearing into space. I fell (or threw myself) onto the ground and heard myself crying, “They have killed our dog!”2

The village woman whose car had hit Valentine was beside herself. “I’m awfully sorry,” she kept repeating, “I can buy you another dog.” Dazed, Marguerite replied, “You see, we loved her so much.”3 As she recalled elsewhere,

At that moment Grace arrived, coming from the back of our woods, and, once again, I heard myself crying, “They have killed our dog!” All together we approached the little one, still inert: Grace bent over and felt her heart still beating very faintly; I felt it, too.

“Go get a little milk, some cognac . . .”

I ran into the house, poured a bit of milk into a measuring cup, and took the little flask of cognac that we keep in case of an accident. But I thought that if by chance she was still living and had internal bleeding, we shouldn’t give her this cognac. I remembered the day, on a street in Munich, that I went to get a whole bottle of brandy in a nearby bar to try and revive a stranger who was dying of a heart attack in his car. The veterinarian? Twenty miles away, and his office closed on Sunday. But when I knelt down with my ridiculous measuring cup of milk, I realized again that she was beyond all help.

“Her heart completely stopped beating under my hand,” Grace told me.4

With the help of near neighbors Elliot and Shirley McGarr, the couple buried Valentine in their wood garden, lining her grave with ferns that autumn had already turned to gold.

Once they were back inside the house, Emily Brzezinski knocked at the door. She and Zbigniew summered up the street, and they had happened by just after the accident. In Emily’s hands were the roses Marguerite had intended to pick “and a tender little note evoking Valentine bounding about ‘in Elyseum fields.’”5 Her epitaph would be a verse from the sixteenth-century poet Pierre de Ronsard, “Portant un Gentil Coeur Dedans un Petit Corps [Bearing so brave a heart within a little body].”

There was no time to dwell on grief. Two days after Valentine’s death, the advance guard of a seven-man television crew arrived from Paris to begin a week of filming. That same day, October 5, Frick and Yourcenar got a new cocker puppy. They named her Zoé, the Greek word for “life”—whether as an affirmation or a plea.

The 1970s were a decade of ever increasing media attention and various honors. October of 1971 brought the first visit of the Parisian literary critic Matthieu Galey, who would host a televised documentary about the author: at home baking bread or typing in the studio, shopping for Indian corn at the Pine Tree Market, atop Mount Cadillac.6 Galey would make several more pilgrimages to Northeast Harbor, collecting the wide-ranging conversations that became With Open Eyes.

In October of 1972 another French camera crew, headed by Michel Hernant, came to Petite Plaisance to talk with Yourcenar about her play Dialogue dans le marécage. Later that month Colby College followed Smith and Bowdoin in bestowing on Yourcenar an honorary doctorate of letters. Frick’s old friend Mary Marshall from Yale University was teaching at Colby that year. In December of 1972 Yourcenar received the Prince Pierre de Monaco literary prize for her entire body of work, though she was too ill to attend the ceremony. Two years later, she would get the Grand prix national de la culture.

In addition to the radio broadcast of Dialogue dans le marécage, other Yourcenar plays were being brought to life on French stages: Le Mystère d’Alceste premiered in Rennes on March 21, 1973. Dialogue dans le marécage was mounted on May 24, 1973, at the Vincennes Festival. The students of Pierre Valde put on Électre ou la Chute des masques on March 19–21, 1974, at the National Conservatory in Paris.7 In August of that year Radio Canada sent Françoise Faucher to interview Yourcenar for five days.8 The following month brought a Belgian TV crew for a week and the renowned photographer Gisèle Freund.9

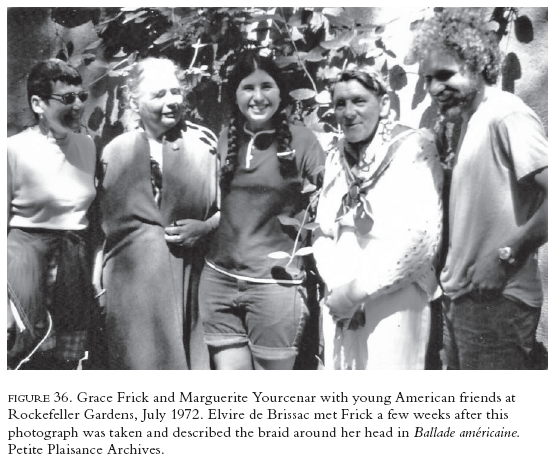

While the media attention brought new readers to Yourcenar’s work, it also brought inopportune callers to her door. In June of 1972 Yourcenar received a breezy letter from a would-be visitor who breached Frick and Yourcenar’s defenses.10 Elvire de Brissac, a young French writer, announced that, “opera glass in hand,” she was off “to take the profile of the universe.” She would be touring the United States that summer, and she would like to visit Petite Plaisance. Enclosed with her letter was a note from the French author Paul Morand, who had commented very favorably on Yourcenar’s first published novel, Alexis, in the pages of the Courrier littéraire.11 No doubt it was Morand’s note that caused the author to receive the young woman. She even reserved a hotel room for her.12

Brissac arrived on September 6, two days earlier than planned. Grace in particular took pains to make her feel welcome. Within minutes of Brissac’s arrival at the Asticou Inn, Frick appeared at the venerable old hotel’s reception desk. As Brissac would write about her trip in the book Ballade américaine, “The Asticou Inn was not a motel that one enters and leaves after paying the bill and Miss Frick . . . was not a person like everyone else.”

“Then again, yes,” Brissac goes on to say,

like one other: the same braid around her head, the same sneeze-contorted face, defying the laws of nature, nose to the right, tongue to the left, arms hanging down to her bobby socks; lumpy as an Italian palace; the same fundamental independence, with inconceivable single-mindedness, the same irreverence for intermediaries, wanting to talk all the time and send you to hell.

I was there.13

Brissac then proceeds to reveal, in a long, stream-of-consciousness paragraph, that the “one other” person whom Grace Frick resembled in her life was the no-nonsense, seen-it-all “Parigote” nanny who raised her and her brother, the thought of whom amused her just as much as Frick did when she first saw her.14 Miss Frick “rolled me up like a spitball, threw me into her car and out of her car, into the arms of a Caucasian who repaired carpets at the Met, onto all fours to catch a glimpse of the seals.”15

Yourcenar would later describe Brissac’s portrait of Grace as taking up “where Rosbo left off in its rudeness and indelicacy.” The author was incensed by what she saw as Brissac’s relentless harassment—indeed, “trampling”—of Frick, whose only conceivable sin toward Rosbo and Brissac was “an excess of goodwill.”16 She was also infuriated by the fact that the red band attached to Ballade américaine for display in bookstore windows used her name as a marketing ploy. Moreover, she had recently completed a long essay on the Swedish novelist Selma Lagerlöf for Éditions Stock, publisher of Brissac’s book. She could not believe that Stock’s director, André Bay, who had worked with her on the Lagerlöf, would stoop so low. How could he have allowed her life to be “indecently evoked” in a book from his house without letting her read and consent to the publication?17 Bay replied lamely that Brissac’s memoir had been produced by a section of Stock with which he was not involved.18 A letter to Stock from Yourcenar’s attorney Marc Brossollet nonetheless got Yourcenar’s name removed from the advertising banner.19

Jean Chalon made the mistake of publishing a favorable review of Ballade américaine in Le Figaro. Though he put a positive spin on the Petite Plaisance chapter, his article did not fail to draw Yourcenar’s ire. Brissac had set out, wrote Chalon, to encounter two “giants” of world literature in the United States, Henry Miller and Marguerite Yourcenar. She was unimpressed with Miller, but her visit to the “monumental” Yourcenar went better: “Elvire de Brissac portrays very well the imposing royalty that emanates from the author of Memoirs of Hadrian: ‘She was waiting for me on two steps, I had the impression of climbing the grand staircase of the Paris Opera . . .’ And what a performance awaited her! Yourcenar preparing a bite to eat. Ah, that Elvire was a lucky one to be invited to the home of the incomparable Yourcenar!”20

Yourcenar was deeply offended by Chalon’s enthusiasm for Brissac’s book, and she didn’t shrink from saying so. After dispensing with the notion that the four birchwood steps of her front porch bore any resemblance to the grand staircase of the Paris Opera, she scolded, “But everything about this little essay seems to strike you as perfect. In fact, the snickering caricature of Grace Frick, of which most of it consists, calls to mind the gleeful chortling of hooligans flinging to the ground and trampling underfoot some nameless passerby—with this one difference, entirely to the credit of the hooligans, that the latter, to begin with, had not sought an invitation to their victim’s home.”21

Chalon was crushed by this letter, which Yourcenar signed “With changed regards.” To his journal he confided, “A terrible letter from Yourcenar has . . . fallen on my head. She has withdrawn her esteem and friendship because I dared to praise a book by Elvire de Brissac that contains one or two disagreeable paragraphs about Grace Fricks [sic], Yourcenar’s friend. As far as blunders go, one couldn’t do much better. I am king of the blunderers.”22

Despite the undeniably disrespectful aspects of Ballade américaine, I don’t think Elvire de Brissac set out to insult Frick and Yourcenar. In fact, she found a sense of “absolute security” in their company that she hadn’t known since childhood. Her description of a drive along the Loop Road in Acadia Park has all the elements of a family road trip. Frick is at the wheel of a rental car, Brissac is beside her in the passenger seat, and Yourcenar, in the back, is doing her best to keep Zoé from biting and scratching the car window.

While Miss Frick drove, with one finger in a splint, I traveled passionately, docilely down two routes: the blinding cliff road, where we were going to perish thanks to the extreme fantasy of Miss Frick’s manner of driving an automobile—stopping abruptly or on the left side of the road, starting up again in reverse to show me a cove—and the no less astonishing road that led me far into the past, to the scene of my earliest childhood in Brissac, where, seated between Mazelle and Nénin, nothing, I mean absolutely nothing, could happen to me.23

Unlike Patrick de Rosbo, Brissac was clearly fond of Frick and Yourcenar. Her transgression was to subordinate the two of them to the purpose of her personal memoir. No pardon would be issued for that blunder.

Another presidential election was coming up in November 1972, and Grace Frick was recruiting votes for the antiwar Democrat George McGovern. To her niece Kathie Peryam she mailed a heavily annotated 1971 campaign letter from the South Dakota senator’s office. “I find it excellent, sober, factual, and sincere,” wrote Frick. “Any vote cast for him, whether or not he finally wins, will inevitably influence the next Administration.”24 As Election Day drew nearer, Grace asked Richard Minear, “Are you pulling for McGovern? We are. . . . Nixon seems to me increasingly unprincipled. The devious strategy of the anti-busing campaign, the growing encouragement of corporate White Africa and Rhodesia, et al. Truly a pernicious man in power, and self-righteous to boot. Furiously yours, G.F.”25 Nixon nonetheless won by a landslide, only to leave office in disgrace in August 1974.

As America’s political health took a sharp turn for the worse, Frick and Yourcenar’s physical health was also declining. In an “inventory” written the next month in one of her notebooks, Yourcenar was seeing everything through a glass darkly:

Heart failure with angina—

Bronchial allergies and rheumatism—

Physical heaviness—

Fluctuating blood pressure, sometimes too high.

G’s physical state bad and getting worse.

Total disorder in the financial and fiscal situation.

The translation of L’Œuvre au Noir almost three years behind. . . .

A possibly irrational but desperate need of change.

Too unwell to travel alone—possibly soon to travel at all—and Grace too exhausted to see traveling as anything other than drudgery.26

Grace, for her part, had been hospitalized for dilation and curettage of her uterus and removal of a polyp in April of 1972. Lab tests on that tissue were fine, but her luck turned a few months later when nodules were excised from the scar on her chest.27 Cancer had begun its relentless return. Yourcenar’s mysterious ill health nonetheless got most of Frick’s attention throughout this period. On October 26 Marguerite began suffering from what seemed to be a bad allergy. She soon had a fever, chills, and “violent perspiration.” Three weeks into these symptoms, doctors were calling them some type of influenza. Marguerite was so sick that Grace had to cancel her own medical appointments to stay home and care for her. By Thanksgiving, as her malady entered its fifth week, Yourcenar could barely come downstairs from her bedroom to the kitchen for a meal. She finally entered the hospital on December 30, and Grace Frick slept from midnight until noon the next day, her first full night of rest in a week.28

Yourcenar underwent every imaginable test “with no result but exhaustion and pain and months of recovery,” as Frick noted with frustration in the daybook. Grace went to see her every day of her nearly two-week stay, sometimes spending the entire day at the hospital. On January 12 a “very weak and much underfed” Marguerite Yourcenar was discharged with no better idea of what was wrong than when she entered the hospital. Both women tracked Marguerite’s night sweats, temperature fluctuations, and daily medications for months. Bouts of perspiration often required the use of a hair dryer. Marguerite was sweating so profusely in the wee hours of one February morning that Grace spent half an hour massaging her, then administered a cup of hot cocoa.29 The patient was well enough to have breakfast that day. Shortly thereafter Frick wrote to Helen Howe that “M.Y. is improving and downstairs some half the day, being now nearly off the third and last drug (a digitalis) given by Gilmore since August 12. This makes three wrong drugs from him and one from Gerdes, the latter for six weeks, the former for months. Inexcusable.” She signed that letter “Grace Frick, nursemaid.”30

Shortly after Yourcenar first fell ill, a delegation came to Petite Plaisance from Colby College, in all its academic regalia, to present her honorary doctorate. Frick described the event in a letter to her brother Gage:

The Colby College Honorary Doctorate was awarded her by the President and two Trustees in person on October 29th (with a delegation of nine, in all, coming from Waterville, solemnly robing themselves in cap and gown in our small house, and going through the exact platform ritual, as they apparently had to do to award it legally. What with two brilliant red doctoral gowns of the Dean of Students and his wife (also a Professor there), from Leland Stanford, it was quite a colorful occasion.

I had invited a few people from the village with whom we had literary connections, so we were some twenty in all, and we served a buffet of (donated) lobster and American champagne. Marguerite came down from bed a half-hour before the ceremony, probably distributed a few germs while making her acceptance speech, but managed to stay up till they left, some hours later; but the price in fatigue was heavy. This is the first time I have not had to battle with her to keep her from working when she has fever. She has really been down. Happily, the naughty puppy is a great diversion.31

It was not until April of 1973—minus the offending drugs—that she finally began to recover.32

Grace and Marguerite both turned seventy that year, and most of their friends had retired. A steady stream of them made a point of visiting the couple through the middle of that decade. Mary Marshall, retired now from Syracuse University, spent a weekend with her friends in September of 1971. They took in all the traditional Mount Desert Island sights: Ocean Drive, Mount Cadillac, Bass Harbor Light, and Seawall, among others.33 Ruth and Charles Hill drove up from Northampton, Massachusetts, for five days the following October, staying at the Asticou Inn. The couple’s one-time deer-spotting friend Helen Willkie, who had lived abroad for a time in the 1960s, came right after New Year’s in 1973, while Marguerite was in the hospital. With Grace spending days in Bar Harbor with her partner, Helen stood in as hostess of the open house one Sunday while she was there.34 Grace’s oldest friend, Ruth Hall, whom she had not seen since 1964, also spent a week visiting the couple that year.35

One person who did not come was Grace’s closest friend from Wellesley, Phyllis Bartlett. Phyllis had retired early from the English department at Queens College on account of ill health. Her husband, John Pollard, had died of a heart attack in 1968, and Phyllis was living alone in the apartment they had shared on East Fiftieth Street in Manhattan. She and Grace had spoken with each other by phone at Thanksgiving time in 1972. Five months later Phyllis died. According to a small article in the New York Times, “The police reported that Dr. Bartlett had been found dead of burns near her kitchen sink, where the water was still running, in a flammable synthetic fur-piled bathrobe and that there were indications that she had been cooking.”36 Grace was devastated by the news, which came to her from another Wellesley classmate. Try as she might, phoning friends all over the country, she was unable to learn anything further about Phyllis’s startling demise.

At Petite Plaisance, through it all, progress continued on the semiautobiographical Souvenirs pieux, delving into Yourcenar’s maternal lineage. On March 16, 1973, Grace went early to Mount Desert Island High School to photocopy the first 294 pages of the manuscript.37 Frick was more involved in work related to this book than has generally been recognized. Many pages of research notes in her hand are preserved at the Houghton Library. She prepared a detailed portrait of Yourcenar’s cousin the Baron de Cartier de Marchienne, for example, a onetime Belgian ambassador to the United States and to Great Britain, whose death merited an obituary in the New York Times.38 She also annotated a very old list of the siblings of Fernande de Cartier de Marchienne for her companion’s use. Yourcenar may have felt particularly appreciative of her assistance with that project, calling Grace with affection rarely shared with a third party “my very precious friend and collaborator” in a letter to Georges de Crayencour.39 And this despite the still unfinished translation of L’Œuvre au Noir.

The malignant lumps found recently on Frick’s chest were metastases from her original breast tumor. She had already had radiation twice, and treatment options were few. As she explained to her brother Gage, “The Bangor clinic has nothing to suggest except a possible hormone treatment, but I have always been leery of that, even in mild form. Admiral Morison’s wife elected cobalt treatment in preference to surgery, but she had a hard three-year struggle before she died this winter, gallantly accompanying Sam on his travels.”40

To make matters worse, the summer of 1973 was excessively rainy, foggy, and cool. “In human memory,” Yourcenar wrote to Jeanne Carayon on August 3, “no one here has ever seen a summer so rainy and so rich in fog.” She found the almost constant lack of sunlight physically depressing.41 Late that month, Yourcenar was hospitalized with a slipped lumbar disk for ten days of intensive treatment: traction, fomentation, massage.42 Frick took a taxi to the hospital to escort her partner home at the end of her stay. That same day, September 7, they transacted the purchase of their joint burial plot in Somesville’s Brookside Cemetery.