CHAPTER 33

One More Midnight Sun

1976–1977

I have seen sidereal archipelagos! and islands

Whose delirious skies are open to the sea-wanderer . . .

—Arthur Rimbaud

WITH THE ACADIA INSTITUTE OF Oceanography off to a good start and The Abyss finally translated, Grace Frick resumed her usual routine of combing through manuscripts before they were sent off to France. Yourcenar’s health had improved after a months-long bout of bronchitis followed by seasonal hay fever. Frick’s was being monitored more and more closely; the Bonadonna drugs upset her digestion, caused eye fatigue, and made her painfully sensitive to bright light. Both women went to Bar Harbor together every week for Frick’s blood test. As Yourcenar told Jeanne Carayon, they took advantage of the trip “to enjoy beautiful landscapes on the way over and back, run a few errands, bring a picnic with us in the car or take tea in a lakeside pavilion.”1

In early April 1976 Frick and Yourcenar’s forty-year-old housekeeper Ramona Turner lost her husband. Ramona had been working for the couple since sometime in 1974. As Yourcenar related to Jeanne Carayon, she was at Petite Plaisance when the phone call came about the death: “Her pain was very Racinian: a little cry, a few suppressed sobs, then ‘I have to go right home.’ Grace Frick exclaimed that she was going to accompany her, even if it meant coming back by whatever means chance might provide. While she went to get their two coats, Ramona, sitting next to the telephone, continued sobbing quietly while with one hand she stroked the head of Zoé, who had put her two front paws on her knees.”2

On September 30, en route to Southwest Harbor in a friend’s car, Grace asked to be dropped off at Brookside Cemetery in Somesville to weed her and Marguerite’s burial plot. Yourcenar wrote in her journal three days later,

This symbolism “We are leaving her in the cemetery” distresses me. But we are always wrong to let ourselves be taken in by traditional symbolism. When we came back to get her two hours later, she was lying in the good sun on what will be her grave pulling up weeds, and the caretaker of the cemetery, Mr. Preston, was galloping along the lanes with our dog, whose gold and mahogany coat was glistening gaily. The atmosphere was divinely lighthearted.

But what did she think about during those two hours? Along those lines, she has nothing to say. I can only guess.3

Things were not going well overall, however. With her immune system compromised by the drugs she was taking, Frick was increasingly subject to opportunistic infections. In mid-September she had an acute attack of erysipelas, a painful rash accompanied by itching and fever, that made her very ill. By early October Dr. Cooper had begun to notice certain mental “short-circuits” that Yourcenar herself and Ramona had been aware of for a few months. “Sometimes her memory fails or gets everything terribly confused; other times her imagination goes galloping dangerously far from the facts,” Yourcenar wrote in her journal. Speaking of Dr. Cooper, she added, “‘It’s classic,’ he tells me, with a doctor’s practical wisdom.” Incapacitating weakness, horrible nightmares, alternating sleeplessness and somnolence, extreme irritability, indifference toward matters of importance: these were some of the debilitating symptoms that were making Frick behave in ways that were often out of character, sapping her legendary energy and eroding her usual conscientiousness. Yet she could also snap out of it, wrote Yourcenar, and be “almost her old Self.”4

Amid all this, Volker Schlöndorff’s adaptation of Coup de Grâce came out in late 1976. A private showing of the film at the cinema in Ellsworth was attended by sixty-five or seventy invited guests on New Year’s Day 1977 despite near-zero-degree cold.5 An unsigned review in the Soho Weekly News, sent to Yourcenar and Frick by Alf Pasquale, begins, “Marguerite Yourcenar is not an easy read, either in the original French or the excellent translations by her long-time companion, Grace Frick. Her prose is dense, rich, extraordinarily complex: Every sentence is loaded with oblique references and understatements, and the meticulously honed prose style may be a labyrinth of subtlety and allusions, but it’s also a goldmine of ideas and sensitivity.” The reviewer then goes on to say that Coup de Grâce “is one of the most magnificent ‘little’ novels ever written, and Margarethe von Trotta and Volker Schlöndorff have captured it with an astounding faithfulness in their film of the same title.”6 Yourcenar disagreed with the latter sentiment, but critics, moviegoers, and other directors—from Vincent Canby to Ingmar Bergman—found the film to be exceptional in every way.

By February 1977 Frick was going “rapidly downhill.”7 For months she had daily fevers ranging from 99.5 to 101 degrees. Time and time again she asked her doctors why her temperature was always elevated, and no one would give her an answer. She had also developed a persistent shallow cough. “Perfectly all right,” Dr. Cooper repeated after each exam. Frick felt that she was being treated like a child. Only when she “raised the roof” one day did Dr. Cooper finally admit that her symptoms could be caused by the Bonadonna drugs.8 The next time Frick saw him, he was a “changed man.”

On February 7, having developed an acute case of shingles in her groin, Frick saw a new young physician, Dr. Haynes, who was particularly knowledgeable about herpes zoster. He and Dr. Cooper put her in the hospital immediately and kept her there for a week. Antibiotics and three daily packs of a special soap solution gradually gave her some relief. Yet another chest X-ray revealed suspicious streaks in the lower right lung. Young Dr. Haynes then ordered a gallium X-ray and took specimens of her sputum. Finally, someone was taking Frick’s symptoms seriously. As always, Marguerite went every day to the hospital, braving frigid weather, storms, and icy roads. Every night Grace called home from the pay phone on her unit. For once, Marguerite was managing to spend the night alone. In the morning, Ramona was there.9

On February 14 Grace returned from the hospital to find “Valentine Blessings Especially For You” waiting in her bedroom. On the inside of the commercial card, spread over two pages, were the printed message “A word bouquet / On Valentine’s Day / For you . . .” and the image of a big bouquet of roses surrounded by the words “Thanks, Praise, Appreciation, Faith, Hope, Joy, Peace, Gladness, Blessings, Love, Happiness, Memories.” On the right-hand side, Yourcenar had drawn a brown heart and, below it, a red one, labeling the sketches “Zoé’s brown heart” and “Marguerite’s red heart” and playfully signing the card, “Your Two roommates.”10 Grace was back home, and, for a while at least, all seemed to be well.

Word soon came that there were cancer cells in Frick’s sputum. On February 22 she would start a new chemotherapy regimen called the Cooper protocol. Along with Cytoxan, fluorouracil, and methotrexate, Grace would get a weekly shot of vincristine to inhibit cell replication and daily oral prednisone.11 As Yourcenar wrote to Jeanne Carayon, they would make the best of it: “We went to Bangor yesterday, some 80 kilometers from here, for a doctor’s appointment. I thought it inhuman to subject her to this little trip on such a cold day in these conditions, but her courage was not daunted by it. Happily, we had a lovely day—freezing, certainly, but sunny and clear, and my thermoses of tea and my basket of sandwiches did not go to waste.”12 Frick, for her part, told Gladys Minear, “Bernice Pierce drove us to Bangor on our first sunny day, and Marguerite went along, against my advice, and said that she enjoyed it, though now she is worn out from a kind of letdown after too much worry.”13

Marguerite had always done the cooking for Grace and herself, having learned to cook back when they were living in Hartford. As Grace’s health declined, it became Marguerite’s primary way of caring for her partner. In 1974, when Françoise Faucher asked Yourcenar if cooking was a symbol for her, she replied, “It may be more than a symbol. In rather pompous terms, you could almost say that it is a calling. You could say, for example, that when you offer food to friends, when you offer it to your family, it is a form of love. It is a way of sustaining life, your own of course, and that of those you love.”14 By early 1977 Frick was losing her taste for solid food. From her hospital bed in Bar Harbor, she wrote to Gladys Minear, “I am quite content to go on with clear liquids forever, I am just that tired of food.”15

It wasn’t long before Grace had also had enough of the devastating side effects of the Cooper protocol. At her doctor’s office in Bar Harbor on April 8 for her usual blood count she announced that she was quitting the regimen.16 Five days later she was back in the Mount Desert Island Hospital.17 There she stayed until April 21, when she was transferred to the Eastern Maine Medical Center.18 The oncologist there, Dr. Parrot, put Grace on Tamoxifen, a drug that had just been approved to combat late-stage breast cancer. When she went back to Bangor on May 23 for her second checkup after leaving the hospital, she was doing so well that Dr. Parrot gave her permission to realize a decades-old desire.19

Grace had dreamed of seeing Canada and the Pacific coast with Marguerite ever since she had gone alone to British Columbia and Banff in 1947 after visiting “Aunt George.” In Victoria and Vancouver Frick was fascinated by the totem poles carved by the indigenous peoples of that region.20 Arriving in Banff, she found the town decked out in ice-coated “glittering moose, elk, and bear carved out of snow” for the winter carnival.21 In front of Frick’s hotel and all along the main street, frozen statues were lined up as if to guard the entrance to a crystal fortress on whose battlements flew gay British flags.22

On February 4 Grace began composing several postcards of a snow-draped Banff to Marguerite. In the first she quotes the title of a popular song, conveying no doubt how she was feeling after two months away from her companion: “‘Show me the way to go home’ but let it be through snow, like this. The train ride across southern Canada from Victoria is reputedly one of the most beautiful in the world in summer, but in winter it is a Paradise. Every minute’s view from the train beautiful all day, and tonight full moon.”23 Whenever she found herself surrounded by beauty in moonlight, Grace longed to share it with the woman she loved.

On that same moonlit night, Frick decided to hike up a canyon near Banff in search of resident wildlife. As she wrote in a multi-postcard “letter” to Marguerite, it was nearly midnight when she set off:

I decided to be prudent for once and ask at a lighted house nearby if it were wise to go on alone. . . . The house belonged to the guardian of the fish hatchery adjoining, and he and his wife had the most beautiful Indian things imaginable, given them by Indian friends over twenty-five years ago when they lived in the West Coast of Vancouver Island, above Victoria. The very things I had been carefully studying for three days in two museums, only more beautiful and far more interesting.24

On the way back from this remarkable encounter in the woods, Frick met two elk “just ambling around looking me over with great unconcern.”25 It was a thrilling experience in every respect.

When Grace got back to Hartford, Marguerite was overjoyed—and quite possibly relieved!—to have her partner back. On February 15, 1947, the date of Frick’s return, she drew an enormous shining sun in the daybook, so large it took up almost the whole page.26

By 1977 much had changed. Not only were Grace and Marguerite Yourcenar thirty years older—well into their seventies—but the health of both women was far from robust. Frick had been living on borrowed time for years. Yourcenar, worn out by worry and the daily disruption of Frick’s repeated hospital stays, was “feeling very ragged and anxious.” She did not dare to set off on such a long voyage without help.27 As Grace wrote to her niece Kathie, Marguerite “held up well during my three hospitalizations of a week each, but after I won my battle to get off the highly toxic drugs, and began to revive with a new treatment, she was near collapse, and was afraid to take off (all reservations being then already made!).”28

Yourcenar did not in fact dare to go without a helper, and both women thought it would be nice for the recently widowed Ramona to have a change of scenery. Ramona said she’d go, but then she changed her mind five or six days before everyone was to depart. Finally she relented—as long as she could have the entire month of July off “to rest up after her return”!29

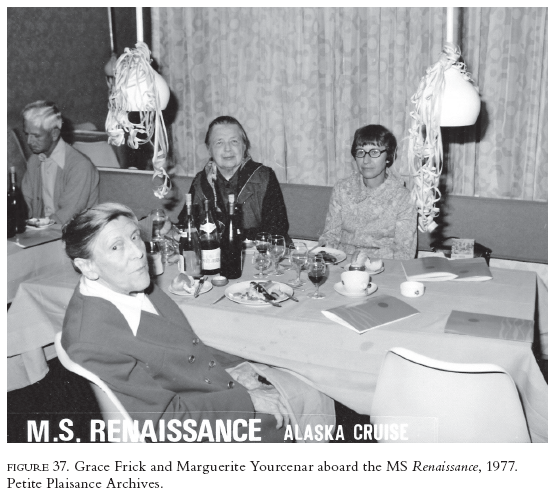

The three women boarded the Trans Canada Railway at Montreal, heading west, on May 31. They would then make a round-trip cruise from Vancouver north along the coast on a ship aptly named in light of what this trip meant to Grace: the MS Renaissance. They did not return to Mount Desert Island until June 20.

One description of this expedition appears in the Pléiade chronology: “Grace Frick, after a grueling stay in a medical clinic, decided to undertake a month-long voyage to Alaska, preceded and followed by a train ride across Canada from east to west, and vice versa. Marguerite Yourcenar accompanied her on that trek and visited with her two of Canada’s great national parks, those of Banff and Jasper, along with the coast of the Inland Sea and the Klondyke [sic] Trail.”30 The one-thousand-mile Inside Passage weaves a course through channels and straits between the mainland and various islands from Puget Sound to Skagway, Alaska. With its towering glaciers, forests of hemlock and spruce, abundant sea birds, whales, polar bears, and other forms of wildlife, the region is a sea and nature lover’s paradise.

Frick, for her part, was elated because, unlike the night in 1947 when she saw elk and a deer but not a single bear, she and Marguerite had the great good fortune to see a grizzly during their one day in Banff on the trip west. Also, as she wrote to her niece Kathie, Marguerite saw “a moose emerging from a pond by the railroad track just before we reached Jasper, and therefore the whole trip is proving a great success for her.”31

Five years later Yourcenar would once again cross Canada by rail, following in her and Frick’s footsteps. This time she was headed, in the company of a young Jerry Wilson, to California, Hawaii, and Japan. Several of the essays in the posthumous collection Le Tour de la prison recount the various stages of that journey. One of them dwells at some length on the voyage with Frick. Borrowing its title from Rossini’s The Italian Girl in Algiers, the essay begins as Yourcenar’s train wends its way toward the Canadian west coast in the fall of 1982. It is night, and the author is ensconced in her sleeping car:

Rossini’s trills, roulades, and vocal phrases accompany me throughout the night between Ontario and Manitoba, in my capsule-like compartment, a cassette player resting on my pillow.32 The rocking of the train merges with the music and creates the impression one is hearing it with one’s entire body. The music is lighthearted, cheerful, bathed in the untroubled sensuality and charms of easy love that Italy has long been reputed to impart, in which the virtuosity of voices that entwine and pull apart corresponds to the interplay and loving art of bodies. Surrendering to them here in this abstract, moving place, this convoy crossing the forest that knows nothing of the pleasures of nineteenth-century Naples and Paris, beneath the square of pale, almost white night that fills the windowpane and will last until dawn, has the charm of incongruity. My reclining body, my ears bathed in sound abandon themselves to that charm in a space all their own. Rossini’s spumante dispenses neither violent intoxication nor sublime exhilaration. Nothing but a warm and innocuous sensual delight. Delicious relaxation.

I had once seen Vancouver in the light of summer, during the precarious lull of a “remission” in the fatal illness that for ten years had tortured the friend whose existence I shared. The disease went further back, but the first ten years had been an almost uninterrupted triumph over it. This time, following a heart attack due to the effects of chemotherapy, one of her habitual bursts of energy had made possible this trip to Alaska, which she had contemplated for a long time. In that land of mist which sometimes turns to fog, we had a month of perfect blue skies. Navigation on the Inland Sea was a long sliding between mountain crenellations hooded with snow, still sufficiently devoid of history to seem new and pure. Blocks of ice fell into the water with a muffled sound. It was not the broad daylight of the Arctic summer, but the length of the evenings and the sun’s rays obliquely slipping between the chaise longues already hinted of the midnight sun. We would not leave the deck till after midnight, surrounded by twilight. Reclining next to that woman who lay beneath her covers on a deckchair parallel to my own, I gazed with her on a long lingering red sky, feeling, as one always does when traveling by sea toward the far north, that we were at the prow of the planet. Nothing will ever have seemed sweeter to me than moments of stillness such as these spent sitting or lying beside beings diversely—or similarly—loved, as we look not at each other but upon the same things, our bodies remaining for various reasons supremely present (I had surely not forgotten, in the present instance, the long weeks of hospitalization), but with the illusion of being for a moment only two matched pairs of eyes.33

As biographers and other commentators have noted, travel was for Yourcenar the corollary of love.34 The cruise to Alaska that Yourcenar remembers in this passage was the last sea voyage she and Frick took together—indeed, the only one taken during the eight years of worsening illness that preceded Grace’s death. It is not by mere chance that the sensual strains of Rossini with which “L’Italienne à Alger” begins, recalling as they do the coming together of bodies engaged in the art of love, evoke the country of the couple’s first passion.

Marguerite Yourcenar well knew, as she lay on that deck chair beside her companion, that Grace Frick had entered the twilight of her life, stepping into what Carlos Castaneda, an author Yourcenar enjoyed, once called “the crack between the worlds.”35 Frick and Yourcenar’s close friends in Northeast Harbor, Connecticut, and Paris had been deeply concerned about the wisdom of embarking on a long, strenuous trip with Frick’s health so precarious. But she insisted, and Yourcenar could not help admiring her for it. For Grace, the trip was both the fulfillment of a long-held desire and a palimpsestic return to the enchanted time when she and Marguerite first discovered Scandinavia, the midnight sun, Saint Lucy’s Day, and other joyful customs that they brought back to Maine and observed every year in their own home.

Writing to Jeanne Carayon on their return, Yourcenar spoke of the “indescribable” beauty of the glaciers, the sea, and the forested islands that she and Frick had feasted their eyes on, linking the particular quality of the subarctic twilight to the most subversive inhabitant of her fiction: “The weather was so lovely and mild that we could spend nearly entire days on deck, which is to say also part of the night at that latitude where darkness barely falls. It was not yet quite the midnight sun that I so loved in the Scandinavian North, to the point of giving it to Zeno for his last vision and a symbol of immortality, but the sunset went on and on in an all-pink sky, reflected by the glaciers till eleven-thirty and beyond.”36

Marguerite Yourcenar guarded her personal life with considerable vigor. She almost never spoke directly of Grace in her work or in media interviews, for reasons no doubt complex and multiple. The fact that she chose, some four years after Grace’s death, to offer in an essay an intimate glimpse of their couple, in a moment of respite from a cruel time, is extraordinary in and of itself.37 That she chose to cast upon that moment a crepuscular glow suggestive of the midnight sun also forges a delicate link between her real-life companion and the fictional character of her own creation whom she loved and admired above all others.