In this portrait, painted some years after the Altdorf demonstration, Harvey’s beady eyes still sparkle. Large eyebrows canopy them, the left eyebrow typically raised higher than the right, giving him a permanently quizzical expression.

Prologue. A new theory (1636): ‘Blood moves … in a circle, continuously’

IN THE SPRING of 1636, William Harvey, physician to Charles I of England, was sent to the Continent by his king as part of a diplomatic mission to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II. Towards the end of May the English party arrived in Nuremberg, a city where Harvey’s name was known to the medical establishment. It was arranged for him to give an anatomical lecture at the nearby University of Altdorf, so that he might demonstrate his controversial theory of the circulation of blood.

On 18 May, the diminutive English anatomist, draped in a billowing white gown and with a round white bonnet fixed on his broad head, entered the anatomical theatre at the university. As he walked over to the wooden dissection table, Harvey’s steps were short, and a little tentative, on account of his being often troubled with gout. On the table various anatomical instruments had been laid out; a chair for the lecturer stood behind it.

The crowd were standing in rows, the president of the university and the higher-ranking professors at the front, members of the general public crammed in together at the back. Harvey looked out at feathered hats, beards, caps, gowns and expectant faces.

The audience in turn gazed back at a round-faced Englishman, with a wispy moustache and an angular chin, barely covered by a thin, pointed beard. Harvey’s face was still smooth and youthful; his stature and energetic demeanour also made him seem much younger than his fifty-eight years. Beneath the large bonnet, his raven-black hair, now flecked with white, was visible in one or two places, with a curl dangling over his left ear. The tail end of the large vein that throbbed on Harvey’s temple could also just be seen.

Harvey’s skin was of an ‘olivaster’ or ‘olive’ complexion; friends compared it to ‘the colour of wainscot’. His cheeks flushed deep red when he was cogitating or whenever his passions were roused – which was often, as he was a notoriously choleric ‘hott-head’. Flashes of Harvey’s emotions, and of his lightning-quick mind, were discernible in his ‘little Eies’, which were ‘round, very black, full of spirit’.

In this portrait, painted some years after the Altdorf demonstration, Harvey’s beady eyes still sparkle. Large eyebrows canopy them, the left eyebrow typically raised higher than the right, giving him a permanently quizzical expression.

The Englishman was known to his audience as the author of the Latin volume Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus, which had been published in 1628 (the title was translated as Anatomical Exercises Concerning the Motion of the Heart and the Blood in Living Creatures; hereafter referred to as De motu cordis). This little book, in which Harvey propounded his theory of the motion of the heart and the circulation of the blood, had made him a famous, and divisive, figure across Europe. While some younger anatomists were open to his radical and innovative ideas, Harvey attracted hostile criticism from much of the medical establishment. His demonstration at Altdorf was part of a long campaign to gain acceptance for his theory, it being especially important that he convinced universities with prestigious medical and anatomical faculties.

Harvey addressed his Altdorf audience in Latin, the common linguistic currency of Europe, and the language of scholarship. ‘I will demonstrate to you today’, he announced, ‘how blood is sent from the heart throughout the body via the aorta by means of the heartbeat. Having nourished the remotest parts of the body, the blood flows back to the veins from the arteries, then returns to its original source, the heart. The blood moves in such a quantity around the body and with so vigorous a flow that it can only move in a circle, continuously. This is an entirely new theory but, as you will learn, numerous arguments and our senses confirm that it is true.’

The men on the front rows, learned in anatomy, medicine and natural philosophy, felt the full force of the claim. Harvey’s declaration represented an unprecedentedly direct and comprehensive challenge to orthodox views on the function of the heart and the motion of the blood, which had been established in Roman times. If accepted, the theory would constitute the most momentous development in anatomy (the study of the bodily structure of humans and animals) and physiology (the study of the functions of living organisms and their parts) since the second century AD. The textbooks would have to be rewritten, traditional medical therapy re-evaluated.

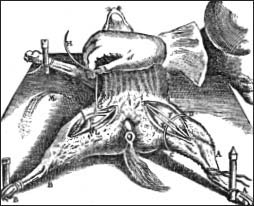

While Harvey had been speaking, porters of the university led a dog into the theatre. Lifting the animal up on to the dissection table, they tied its jaws shut with some rope so that it could not bite or howl. Then they pinned it down on its back and forced its limbs apart, tying its paws to four wooden stakes on the table, so that it lay spreadeagled.

A seventeenth-century illustration of the vivisection of a dog. Vivisection, a Latinate word meaning ‘the cutting of the living’, was coined in the eighteenth century.

‘It is obviously easier’, Harvey commented, by way of explaining the dog’s arrival, ‘to observe the movement and function of the heart in living animals than in dead men’. Then he took a knife from the table, moved forward, and bent over the animal. With a determined thrust he plunged the blade into the dog’s thorax. As he did so his sleeves became splattered with blood, while the dog writhed violently beneath him in appalling pain.

Having successfully laid bare the beating heart, Harvey put down his knife, and picked up a rod. With this he indicated the rising and falling of the dog’s heart. ‘You can see’, he commented, ‘that the heart’s active phase is contraction: when it drives out the blood as it were by force, as I shall now demonstrate.’ Harvey lay his rod on the table, and took up his knife once again: ‘While the dog’s heart is still beating’, he continued, ‘we will see what happens if one of the arteries is cut or punctured during the tensing of the heart.’ Harvey held his knife over the dog’s pulmonary artery, waiting for the moment when the heart was in contraction; then, in one sure and quick movement, he cut the artery and stepped back.

The dog’s blood ‘spurted forth with great force and raging ran forth in a headlong stream’ (on occasion it travelled as far as three or four feet away from the animal, showering spectators in the front row). Amidst the tumult that invariably ensued, Harvey remained calm, and asked the audience to observe how the blood continued to gush out of the dog’s heart when it contracted. He also asked them to note the force of the expulsion and the copious amount of liquid expelled, adding that even a conservative estimate of that quantity would have to be multiplied by seventy-two (the average heart rate), and then by sixty, to arrive at the average amount of blood discharged by the heart in an hour.

The uproar of the audience would have eventually subsided, along with the dog’s dying groans and convulsions. Harvey put down his knife before delivering his conclusion. ‘Calculations of the amount of blood leaving the heart and visual demonstrations of its force, confirm my supposition; I am therefore obliged to conclude that in animals the blood is driven round in a circuit with an unceasing circular movement, and that this is an activity or function of the heart which it carries out by virtue of its pulsation.’ And with that, the small Englishman retired to his seat.