3

WRONG CAREER CHOICES

If men could learn from history, what lessons it might teach us! But passion and party blind our eyes, and the light which experience gives is a lantern on the stern, which shines only on the waves behind us!”28

“Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.”29

Of course, humans have been ignoring the lessons of history since the beginning of time and sincerely believing they know more than they actually do. Occasionally, there come along some individuals who really excel at these faults. Take, for instance, the two men and one woman who attempted to rob two different Kansas banks in the early morning hours of March 24, 1917.

Their attempt to rob the First National Bank of Overbrook, Kansas, resulted in a lot of noise, a lot of damage and a lot of nothing for the burglars. Sometime between one and two o’clock in the morning, three men tried five times to open the safe with nitroglycerin charges that did $2,500 damage to the bank itself, but the safe still guarded its contents of $10,000, which remained untouched behind the second inside door. The blasts did rip the outer door off the safe, destroy furniture and fixtures and break plate-glass windows.

The robbers had cut the telephone wires, but they hadn’t counted on Miller Burress to be on the street about three blocks from the bank. When he heard the first explosion, he ran toward the bank and then heard a second explosion.

Burress did not approach nearer but began shouting for help. He attempted a ruse which worked successfully. He attempted to make the bandits believe that the town was already organized.

“Five of you men go south, the rest of you go down that street there. Now come here fellows and watch this street,” he shouted.

Burress gave orders like he was placing forty or fifty armed men at advantageous points around the bank. The lookout, standing in front of the bank reported to the men inside and after a fifth charge had been exploded all three rushed out of the bank, jumped into the automobile and drove out of town.30

The attempted robbery of the Kelly State Bank at Kelly, Kansas, was carried out in a similar fashion. On the evening of March 24, the citizens noticed a black touring car with two passengers driving the streets of town. After the robbery attempt, the citizens believed these men were casing the bank.

Later that night, prior to the robbery attempt, the car pulled up to the telephone office, and one man jumped out and began cutting the wires. Immediately, the switchboard failed to work, which prompted the operator to open the outside door, only to be met by a masked man with a gun. “Get back,” he was told. “Get back inside, or I’ll blow your d— head off !”31

Soon, residents of the town heard four blasts as the bandits detonated four charges of nitroglycerin in an attempt to open the bank’s safe. Two armed men stood guard outside on the street, and a woman sat at the wheel of another car. The following morning, officials discovered a woman’s footprints near railroad tracks where the bandits apparently found tools to pry open the bank’s door.

After the bandits left, the cashier of the bank arrived on the scene and determined that the explosions had wrecked the interior of the bank and that the safe had also been blown open. The stolen money consisted of about $250 in gold and silver and more than $600 in paper money. However, there was some paper money left in the safe and scattered about the interior. This currency was so badly mutilated that the authorities believed that any taken by the robbers would also be badly mutilated, making it almost impossible for the robbers to spend, and if they did, it would provide clues to where the bandits had been.32

The two banks were believed to have been robbed by the same gang of robbers because of the similarities in the way they worked. Even if they could spend some of the currency, it would have been slim pickings for seven or eight people—hardly worth the risk and effort.

Now, what could the bandits have learned from history to increase their chance of being more successful? The history of banking reveals that there was a back-and-forth struggle between building a better safe for holding the valuables of the bank and developing a better locking device that was equal to the container.

First in this evolution of safes for banks to protect gold, cash or important documents was often a wood box covered with metal, which appeared to be very impenetrable but in reality could be breeched with a hammer and chisel or a strong crowbar. It was easier to break into the safe than to pick or break the lock. When the safe design became superior to the lock, the bandits or burglars developed skills to beat the lock.

When safes couldn’t be breached with common tools and the lock couldn’t be picked by professional thieves, they resorted to dynamite or nitro to blow open the safe or vault. Safes or vaults were not all created equally, and knowing the difference was essential for the bad guys, as demonstrated by the attempts at Overbrook and Kelly.

This safe and vault evolution continued until it reached an astounding degree of protection. Perhaps the finest example of this were vaults manufactured by the U.S. firm of Mosler Safe Company. In 1925, the Teikoku Bank of Hiroshima, Japan, installed a Mosler vault and safe. This bank was located 360 meters (390 yards) from the hypocenter of the atomic bomb dropped on that city on August 6, 1945.

The building that housed the bank was rebuilt around the vaults, and in 1950, an official of the Teikoku Bank wrote the Mosler company a letter that, in part, stated:

As you know in 1945 the Atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, and the whole city was destroyed and thousands of citizens lost their precious lives. And our building, the best artistic one in Hiroshima, was also destroyed. However it was our great luck to find that although the surface of the vault doors was heavily damaged, its contents were not affected at all and the cash and important documents were perfectly saved…Your products were admired for being stronger than the atomic bomb.33

There was also a lesson here for all banks and bankers. According to John Mosler, vice-president of Mosler Safe Company of Hamilton, Ohio, “Seventy-five per cent of all safes in use today [1951] are potential ‘ovens’ that can turn assents [sic] into ashes, noted safe expert and record protection specialist warned…To stress the danger of this situation, he cited this conclusion from a recent survey: ‘Of all firms which lose their records by fire, 43 per cent never reopen their doors. Of the firms which remain in business, 14 per cent suffer a reduction of 30 to 66 per cent in their credit ratings.’”34

So the evolution continues with both the bankers and the crooks learning lessons and adjusting to the changing challenges.

A robbery on April 30, 1884, would make a textbook script of a western movie or TV episode because what would be portrayed on the screen actually happened in a small Kansas town.

Opening scene: The dusty street of a western cow town is flanked on both sides by stores with high false façades and signs that announce they purvey anything a lonely, thirsty or rowdy trail hand could desire. On the far end of the main street, across the railroad tracks, longhorn cattle fill the loading pens or graze on the surrounding prairie.

Amid the sounds of creaking wagon wheels, plodding hooves and cussing teamsters, two pistol shots ring out, and a figure stumbles off the sidewalk into the street and collapses. He rolls over on his back and tries to raise his Colt Peacemaker before dying with his sightless eyes staring at the prairie sky. The noonday sun winks off a marshal’s badge pinned to his vest next to a red stain on his shirt.

This marshal was one of several lawmen who died trying to tame this town. It was just one of the killings and general hell-raising that prompted a Wichita editor to write, “As we go to press hell is again in session in Caldwell.”

Caldwell, Kansas, was established in 1871 and became a shipping point for Texas cattle drives when the Santa Fe Railroad tracks reached the town in 1879. It quickly gained fame as a wild and woolly cow town that soon became known as the “Border Queen” because it sat just on the Kansas side of the Oklahoma border. Some say that during its heyday Caldwell had a higher murder rate and lost more lawmen than any other cow town. Between 1879 and 1885, eighteen city lawmen were gunned down on its dusty streets or in one of the rowdy saloons.

In July 1882, the Caldwell City Council appointed Henry Brown assistant city marshal. He was appointed city marshal in December of the same year. Several weeks later, an old friend of Brown, Ben Wheeler, came to town and was appointed assistant marshal. The two lawmen quickly began to tame the town, and it isn’t surprising that the town folks were thankful. So thankful, in fact, that on January 4, 1883, they presented Brown with an engraved, gold-plated Winchester rifle for his service to the community.35

The presentation Winchester rifle given to Marshal Henry Brown by the city of Caldwell, Kansas. Brown carried it when attempting to rob the Medicine Lodge, Kansas bank. Kansas State Historical Society.

Now the scene changes to Medicine Lodge, Kansas, which gained notoriety in October 1867 when the U.S. government and the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche and Kiowa tribes gathered to negotiate a new treaty. There wasn’t much trust on either side, and in reality, the treaties reached at that time failed to end the wars between the Indians and whites.

Despite the treaty’s failure, the location became the site for the town of Medicine Lodge, which was incorporated in 1879. It sits just north of the confluence of Elm Creek and the Medicine Lodge River. As the crow flies, it is approximately seventy miles northwest of Caldwell.

On April 30, 1884, the scene’s focus narrows to four men riding into Medicine Lodge during a heavy rainstorm. They came from the west and tied their horses to the Medicine Valley Bank’s coal shed located just behind the bank. The bank had just opened, and the cashier, Mr. Geppert, was doing paperwork while bank president E.W. Payne sat working at his desk. Three of the riders entered the bank through the rear door. The bandits ordered the men to throw up their hands, which the president did, but the cashier pulled a revolver, which prompted four shots from the robbers; two bullets hit and killed cashier Geppert while a single bullet critically wounded Payne. The city marshal, who was nearby, heard the shots and opened fire on the robbers, causing them to abandon the robbery and make a hasty retreat out of town.

The scene now turns to the obligatory pursuit by a posse pounding after the robbers. In this case, the posse was a determined group of well-mounted and well-armed citizens. The posse sighted the bad guys just beyond the Medicine Lodge river crossing south of town. A running gunfight followed, and the robbers were forced to abandon their horses after one of them could go no farther. The holdup men made their stand in a canyon some three or four miles southwest of town. A worse place for a final stand and shootout would be hard to find. The four bandits were at the bottom of a “bowl” with the posse on the high ground. During the standoff and gunfight, a couple of the posse returned to Medicine Lodge for reinforcements. Part of the reinforcements apparently were barrels of kerosene that they intended to pour into the bowl, which by this time had flooded from the heavy rain.36 The posse evidently intended to roast the bank robbers, but the outlaws surrendered before the roasting could commence.

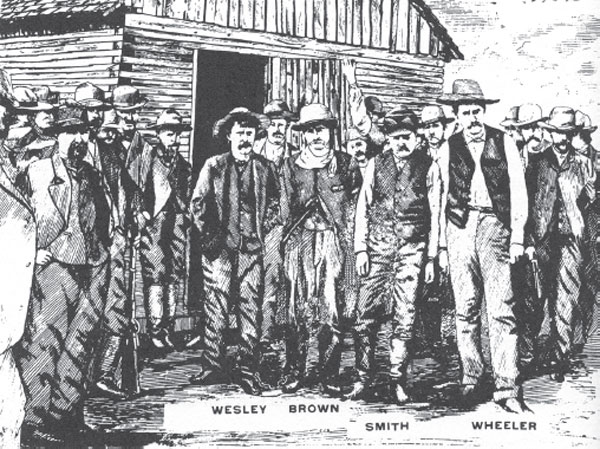

Now comes the plot twist: the outlaws were none other than Caldwell’s marshal Henry Brown; his deputy, Ben Wheeler; William Smith, a T5 (ranch brand) outfit cowboy well known in the area; and John Wesley, another well-known cowboy.

The posse that captured the Medicine Lodge bank robbers. LevyType Co. Chicago.

Medicine Lodge bank robbers after their capture by the posse. LevyType Co. Chicago.

What Marshal Brown had failed to mention to the Caldwell City Council was that he had ridden with Billy the Kid during the Lincoln County unpleasantness and the Kid’s ambush at McSween’s Store during raids in New Mexico. Later, it was suspected that his gang was responsible for other robberies in the area where they apparently worked both sides of the law.

Brown and gang were escorted back to the town jail, where another obligatory scene played out: angry residents surrounded the jail and were determined to pass sentence on the murders, crying, “Hang them, hang them!” The armed crowd demanded the prisoners, but the sheriff refused until he and the posse were overpowered and the jail doors opened. The prisoners knew what awaited them, so in desperation they made a bid for freedom. Brown ran a few steps and fell dead as numerous gunshots rang out. Wheeler was wounded, and the other two were grabbed at the jail door.

Smith, Wesley and the wounded Wheeler were taken to an appropriate tree east of town. After the doomed were given a moment to say any last thoughts, they were left swinging at the end of ropes. Justice was served frontier style.

The scene shifts to the story’s obligatory romance: after Brown was jailed and before the mob opened the jail doors, he wrote a letter to his wife, whom he had married after moving to Caldwell. History records that Brown did not drink, smoke or chew. He and his wife had bought a house in Caldwell. His letter read:

Medicine Lodge

April 30, 1884

Darling Wife: I am in jail here. Four of us tried to rob the bank here, and one man shot one of the men in the bank, and he is now at his home. I want you to come and see me as soon as you can. I will send you all of my things and you can sell them, but keep the Winchester. This is hard for me to write this letter, but it was all for you, my sweet wife, and for the love I have for you. Do not go back on me; if you do it will kill me. Be true to me as long as you live, and come to see me if you think enough of me. My love is just the same as it always was. Oh, how I did hate to leave you on last Sunday eve, but I did not think this would happen. I thought we could take in the money and not have any trouble with it; but a man’s fondest hopes are sometimes broken with trouble. We would not have been arrested, but one of our horses gave out and we could not leave him alone. I do not know what to write. Do the best you can with everything. I want you to send me some clothes. Sell all the things that you do not need. Have your picture taken and send it to me. Now, my dear wife, go and see Mr. Wezleben and Mr. Nyce and get the money. If a mob does not kill us we will come out all right after a while. Maude, I did not shoot anyone, and did not want the others to kill anyone, but they did, and that is all there is about it.

Now, good-bye, my darling wife. H.N. Brown37

The scene changes again to a young woman sitting in a rocking chair weeping over a letter that has fallen from her hands onto her lap.

Brown’s prized Winchester rifle was stolen before his personal items could be sent to his wife. This gun has now been acquired by the Kansas State Historical Society in Topeka, Kansas.

Bank burglary, fast automobiles and some drugs just don’t mix. Proof that should make that abundantly clear is found in the story of a bank burglar named “Blackie” who, along with two others, attempted to rob the First National Bank in Dighton, Kansas, on the night of June 27, 1922.

Dighton, located in Lane County, is a typical small rural town twenty-five miles east of Scott City. Arle Boltz was an employee of the bank and was a member of the posse that captured the burglars. Boltz described Dighton as “a real sleepy town. All electricity was turned off at 12:00 p.m. and street lights were turned off at 11:00 p.m. and there was no night watchman.”38

The July 7, 1922 issue of the Dighton (Kansas) Herald under the headline “BANDITS IDENTIFIED” ran over ninety column-inches of copy in an effort to correctly record the events of the bank robbery:

Bandits has been the talk in Lane county [sic] for the past week. Baseball and harvest have been forced to take a back seat and wild and weird are the stories that have been afloat.

Last week we had to hurry our story so much in order to get the type set that many important details were left out. This was partly due to the fact that everyone was so excited that they were hard to talk to. There were so many versions of the battle that we could not arrive at any definite conclusion. It is human nature that no two persons can see the same thing alike and had we been an actual eye witness we would undoubtedly have had a version all our own. If in reading these notes you see a report that does not conform exactly with the way you saw it, please refrain from thinking we are trying to string some one and remember that this is the way some other man’s eyes recorded the event.

The rest of the story unfolded like a novel that began with a life of crime for the three burglars who made their appearance in Dighton on that Monday evening. They were noticed at a camping ground near the city but didn’t appear to be preparing to spend the night there because they didn’t pitch a tent or prepare a campsite.

Later, the same car was observed cruising about town and then stopping in front of a store where the occupants got out and then sat down on the sidewalk in front of the store. Much later in the evening, three men were seen on the east side of the bank building. At this time, no one had connected all the dots.

However, it was only a couple hours later that events began to unfold that connected all the dots with the three men who had been seen around town the previous night. About two o’clock on Tuesday morning, the alarm on the bank began to sound, which awakened many residents who dressed, armed themselves and rushed toward the bank. This was done quickly, but it did allow just enough time for the bandits to get a head start on the posse.

A bank employee entered the bank expecting to find that the alarm had malfunctioned as it had done in the past. But when he encountered a hole in the vault’s brick wall, he ran outdoors expecting a charge of explosives to go off any minute. Outside, he fired three shots in the air, which was a signal to let the town know that a robbery had occurred. Another bank employee who lived just outside town was running toward the bank when a car went by at a high speed. Although armed, the employee didn’t fire for fear of hitting some innocent person. He did fire one shot, letting the others know that he was on his way. Apparently, the town had a well-planned method of signaling in times of emergency. Also the telephone exchange began to notify the community that a bank robbery had taken place and to be on the watch for the bandits fleeing in a black touring car.

Back at the bank, no explosion occurred because the alarm had sounded before the burglars could gain access to the vault where they may have used explosives to get through the metal wall of the vault. The sheriff quickly organized four cars full of well-armed men, who roared out of town on the trail of the black touring car with three burglars who were doing their best to throw off the pursuers.

Law enforcement back then didn’t have cellphones and satellite imaging, but it did have an ingenious method of helping keep track of the bandits, which in this case worked to perfection. In the 1920s, there could be as many as four sets of farm buildings on a section of land, and most of them had a windmill that could serve as an observation post for the community.

The man of the house would climb up the windmill tower and report down to his wife if he saw any autos on the roads. She would then call the sheriff ’s office and report any sightings. The evening of the robbery attempt, a light rain had fallen, which made following the tire tracks in the dirt roads easy. That, coupled with the sightings from the community, helped the sheriff and posse stay on their trail but always about thirty minutes behind, as the bandit changed directions and backtracked in order to confuse any pursuit.

The burglars were driving a new Marmon touring car that they had stolen from an auto dealership in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The Marmon was a well-designed and well-engineered automobile with a reputation for speed that made it a favorite of some bank robbers. It was said to be able to cruise a gravel road at ninety miles per hour. Apparently, there were no specs available to the driver as to how fast it could negotiate a square corner. They failed to negotiate such a turn and crashed into a telephone pole and rolled the Marmon. When the posse arrived on the scene, they examined the wrecked auto and discovered a lot of blood on the car’s interior and knew that some of the bandits were injured. At this point, it became a foot search over some pretty wide-open spaces.

As it turned out, a little girl and a windmill led to their capture. After observing the older folks climbing the windmill to look for the burglars, little Willetta Finkenbinder climbed the windmill and told her mother that she saw the three men crawling through the wheat field on their farm. The mother didn’t believe the daughter but climbed up to have a look. Sure enough, there were three men crawling through the wheat field some distance from the buildings.

Hurrying down from the windmill, she rang the wall telephone and spread the news, which brought the posse in minutes. Spreading out and approaching a clump of weeds the outlaws were said to be hiding in, the posse was met with a hail of bullets that the newspaper described as sounding “like machine gun fire. It was put-put-put, just a steady stream of death-dealing bullets. In the first of the firing Bradstreet fell. He was immediately loaded into the Durr car and carried back to safety, where he could get medical aid.”39

This didn’t discourage the posse members, and they responded with their own gunfire. Then one of the men in the weeds stood up, began firing and was riddled with bullets from the posse. He was dead, and soon the other two men surrendered. The captured men were taken by the sheriff and his deputies to Ness City, where the prisoners were given appropriate medical attention before being taken to Garden City and placed in the Finney County Jail. As for Blackie:

When the car carrying the dead man arrived in town, pandemonium reigned. Every one wished to view the bandit. It was with difficulty that the car proceeded up the street from the Hotel Dighton to the First National Bank, where he was unloaded and taken to the undertaking rooms upstairs.

A steady stream of the curious filed up and down the stairs all that afternoon, eager for a look at the bandit…Sheriff Richardson of Finney county [sic] took the dead man’s finger prints and a photograph was taken. These were sent to Leavenworth to the bureau of criminal identification of the federal prison.40

When the dust settled, it was learned that the dead man was called Blackie. However, his real name was Thomas Martin, and he had family in Pennsylvania. Why he was called Blackie is unknown. The two men who helped Blackie in the burglary were C.H. Barton and Arthur Lang. Barton lived with his wife in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, and Lang gave his address as Kansas City. All three had used various aliases during their criminal careers, and all three had served time in different state penal institutions.

Evidence was found that implicated the gang in the burglary of the Fowler bank on Friday night and the Winona bank on Sunday night before driving to Dighton to rob the bank there.

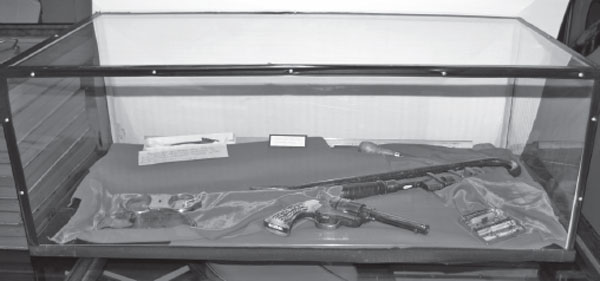

A drug kit containing a syringe and three vials with three different powdered substances was found at the crash site, and it was assumed it belonged to one of the burglars. Besides the syringe, the three vials contained powders of nitroglycerin, strychnine, caffeine and sodium benzoate. All these substances were used in medical remedies in the past. The kit’s purpose has remained a mystery, but it may have been used in past burglaries to blow a safe, or it could have been carried for medicinal reasons. No additional references were found to the drug kit except a note in the display at the Lane County Museum where it was labeled a “Dope box with syringe and pep dope taken from Dighton bank Robbers June 1922.”

The passing of time can certainly change people’s views of the past, and sixty-nine years later, the town of Dighton had seemingly forgiven Blackie and his gang. Immediately after the bandits were killed or captured, Blackie’s body was displayed in front of the bank he’d tried to rob. It was reported that local citizens clipped some of Blackie’s hair to keep as souvenirs.

Items taken from the robbers after a failed bank robbery in Dighton, Kansas, include a .38 Colt revolver; handcuffs; a dope kit containing nitroglycerin, strychnine and caffeine; plus miscellaneous other items. Courtesy Lane County Historical Museum. Photo by author.

Since no family members claimed Blackie’s body, it was buried in Dighton’s Potters Field, where the site was marked only with “a small irregular shaped rock.” Years later, a series of events prompted Bill Ragel of Ragel’s Monument Service in Garden City to replace the small rock. Ragel said he believes it sacrilegious for anyone to be buried without a headstone and that “every tombstone is a part of a communities [sic] history.”41 So he donated a headstone for Blackie’s grave, and since that day in June 1991, Blackie’s resting place has been graced with a tombstone to remind people of that historic day in Dighton.