“Pressure? What pressure?”

THE LEAFS used an old bucket of a chartered Air Ontario plane that felt like it was held together by spit and chicken wire. “You’d be sitting there on takeoff, clutching the armrests, never knowing if the damn thing would get up enough speed to lift off the runway,” says Doug Gilmour, shuddering at the memory. Only later on, at the start of the conference final against Los Angeles, did owner Steve Stavro upgrade the team’s transportation arrangements, renting a sleek and spacious 727 with polished attendants serving catered gourmet box lunches. One reporter from each major news outlet was permitted to hitch a lift with the club.

The spring ’93 playoffs were a heart-stopping thrill ride: twenty-one games in forty-two nights for Toronto—three consecutive seven-game series. No other NHL team had done that before, and Pat Burns burnished his reputation as coaching virtuoso. It would be a dreadful metaphor to say the postseason flight eventually crashed and burned for the Leafs, and all those along for the breathtaking spring whirl. But everyone who was there, up close, will never forget the experience—the hockey, the whole splendiferous and exhilarating adventure.

“If I told you, I’d have to kill you.” That was Gilmour toying with a reporter who’d inquired about the Leafs’ strategy against Detroit, Toronto’s first-round opponent. Pat Burns had been equally cagey about what he had in mind as the series opened. Toronto had allowed only 241 goals in 84 games for a 2.87 GAA, the best since 1971–72. Cliff Fletcher had constructed a compelling club out of the wreckage left behind from the ’80s. But this was also the oldest team in the NHL, with an average age of twenty-eight. And now Toronto was going up against the offensively flashy Red Wings and their formidable power play. Hustle and desire had been contagious among the Leafs, but would that be enough to cramp the superior talent and prowess of Steve Yzerman, Chris Chelios and their Motor City crew? “The crack in the door is there for every team,” reminded Burns, noting Toronto and Detroit had split their head-to-head series through the regular season. “I know I believe that, but I don’t know if all the players believe it.” Then, mimicking the traditional Olympics declaration: “Let the games begin!”

Stavro had Maple Leaf Gardens director Terry Kelly hand-deliver a lucky tie to Burns on the eve of the series. He chose not to wear it for game one at the Joe Louis Arena. It might have helped, as things turned out. If the coach did have a game plan, it must have gone unheeded. Leafs turned the puck over in their own end, took bad penalties, failed to contain the Red Wings’ speed, missed passes, blew checking assignments, couldn’t even execute a viable dump-and-chase and got pushed around absurdly. The Leafs looked not only nervous but afraid. At one point, trash-talking thorn-in-the-side Dino Ciccarelli—he’d staked out territory directly in front of Félix Potvin, practically planted a flag, and was left unmolested—screeched insults right in the young goalie’s face, and nobody made a move to dislodge him. “If a guy’s going to put his rear end in our goaltender’s face, we’ve got to do something about it,” Burns complained.

Before the game, Todd Gill paced anxiously in his underwear outside the Leaf dressing room. The teamwide tension could be cut with a knife. The Leafs took the boisterous crowd at the Joe out of the equation by scoring first after killing off a two-man disadvantage, but they were frantic, undisciplined and overwhelmed thereafter, thrashed 6–3. Octopi plopped on the ice in whoop-whoop celebration. Burns had to salvage something from the atrocity to alleviate his players’ despondency. “It was one of those nights. What you don’t want to do is bury your head. You’ve got to stick it up proud and get right back at it.” An invitation to the dance is how Burns had characterized Toronto’s first playoff inclusion after more than a thousand days and nights in the wilderness. But the Leafs had been stomped, staggering in their incompetence. The coach was among those who marvelled at Detroit’s awesomeness. “You should have seen it from ice level. Whoosh—and they were gone. That team can kill your dreams in ten minutes.”

Ten minutes, five shots, four goals: goodbye dreams.

Bad-ass Bob Probert, the NHL’s heavyweight champ, mocked Wendel Clark, practically slapped a white glove across the captain’s face. “You really couldn’t find him out there on the ice,” he sneered. Probert had almost ripped off Potvin’s arm in one drive-by collision and then mugged passive defenceman Dmitri Mironov with nary a shove-back. “Probert was pretty much allowed to do what he wanted,” Burns groused. “But I don’t have a forklift to move him out of there.”

There was more bad news: Toronto right winger Nikolai Borschevsky collided with Vladimir Konstantinov in the third period, striking his head on the lip of the boards. He fractured the orbital bone below his right eye. When Borschevsky tried to blow his nose, his eye puffed up grotesquely because air was forced through the crack in the bone. The injury was expected to keep the not-so-husky Siberian out of the lineup for at least seven days, doctors saying he wouldn’t be able to play with a face shield once the swelling went down because air could leak into the eye and explode the orb. Meanwhile, Todd Gill suffered back spasms after lunging for a puck. The eviscerated lineup had Burns wringing his hands over what might ensue in game two. “Often, you get the smell of blood when you lose players. The other team gets going like wolves.” As personnel adjustment, Burns dressed Mike Foligno, who’d been a game one scratch. “Maybe Foligno might have a couple bounce in off his bum.”

Next morning, propped on a stool and balancing on the tip of his skates as he faced reporters, Burns tried to sound philosophical. “When I got up this morning, the sun was still shining,” he said, evoking Pierre Elliott Trudeau after the Night of the Long Thousand Knives. That evening, a bunch of Leafs went to Tiger Stadium to take in the ballgame against Seattle. Handing out ducats, PR director Bob Stellick added, “You also get a coupon for a free hot dog and drink.”

Toronto put in a better effort in game two, showed more zip, but the result was the same: a 6–2 loss. As the score mounted, things got ugly with lots of slashing, spearing and stick swinging. Potvin grew so exasperated with Ciccarelli’s abuse that he laid a two-hander across his irritant’s shins with his goal stick. The Joe crowd, meanwhile, taunted the oddly docile Clark: “WENDY! WENDY!” In the regular season, Clark had outpunched Probert in a memorable title fight, but now he turned the other cheek. Probert was a menacing presence every time he stepped on the ice, while Toronto’s lauded team grit had turned to team silt. Clark had sought calmer waters at the edge of repeated frays, noticeable only for his absence—the absence of malice. He was excoriated by reporters for his meekness. “Pat had told me not to fight Probert,” Clark says now. “But I wasn’t allowed to say that I’d been told not to fight him.”

Perhaps there had been a breakdown in communication between coach and captain. “I told Wendel and the others that they had to create some havoc to get this thing turned around,” said Burns. “Nobody’s asking him to fight Bob Probert—that’s not it at all. Probert’s not the problem. We’ve got to hit their good people and not waste our time and energy on guys who can’t really hurt us.” Burns was livid over Probert questioning Clark’s manhood and stories written about Toronto’s captain. “You can question Wendel’s ability to score. You can question his ability to shoot. But nobody will ever question Wendel’s toughness or his heart. That’s bullshit, pardon the expression. Wendel Clark is not a guy that’s going to skate away from anything. Nobody here will ever question Wendel Clark’s courage.” Steaming, the coach stalked off. Yet later, privately, Burns took aside a columnist who’d been especially merciless in print about “Pretty Boy” Clark. “You’re not entirely wrong,” he confided.

Detroit coach Bryan Murray claimed to be appalled by all the lumberwork. “It was certainly one of the most vicious games I’ve been involved in. There are lots of people who don’t want fighting but, if that’s the result of no fighting in hockey … boy.” For Burns, the only saving grace was leaving Motown behind for a while, with few chroniclers of the Leafs misfortunes—outscored 12–5—expecting the team to return there that spring. “We’re a good club,” Burns said defiantly. “At least we’re going back home. Let’s wait and see. I hope our fans are as vocal as theirs.” He repeated the Leaf gospel preached all season: “Everything this team has accomplished has come from hard work and second effort. It seems to me, we coaches showed them all these films and diagrams and explained matchups at length, and at some point, they said to themselves, ‘Hey, this is going to be easy, as long as we follow those plans.’ Well, it’s never easy. Never has been. Never will be.”

In Toronto, Burns convened a meeting to address leadership, dismissing the idea that Clark was guilty of leaving a void in that area, pointing fingers instead at veterans who’d won the whole enchilada elsewhere. “The guys with Stanley Cup rings have done (bleep). But I’ve talked to them about it and I made them talk a bit too. If we believe we’re beat, then we’re beat.” Team psychologist Max Offenberger was tapped to make a dressing-room house call. Of more direct influence was Burns’s decision to neutralize the distraction of Ciccarelli. Simply put: Ignore him. Let the guy chirp and harass Potvin. Render him invisible. Potvin signed on to the strategy. “I’m not going to touch him. I won’t let him bother me. I’m going to try to see through him.” Potvin says Burns made a point of bucking him up. “He came to me in the room saying, ‘I don’t want you on the ice today for practice. Make sure you rest and are ready for game three.’ Right away, that cleared any doubts I may have had in my head.”

Following a brisk practice, assistant coach Mike Kitchen booted a garbage can in anger when he saw the media swarming around Clark’s stall. The captain was his usual stoic and straightforward self when queried about whether he still had a leadership role on the club that extended beyond the ice. “I don’t know. I’m not that deep. I’m a farmer, for God’s sake. I show up and play, and that’s the only part that’s in my control.”

The team’s psyche was fragile, and its big guns had gone silent. Gilmour had two goals in two games, one on the power play. Dave Andreychuk, saddled with a reputation as a playoff vanishing act from his years in Buffalo—“Andy-choke”—had yet to score. Gilmour suggested the squad had been too uptight in Detroit. “We’ve been nervous. We’ve been scared out there because we didn’t want to lose.” Crucially, as Burns emphasized, they needed to wise up, avoid being drawn into taking penalties that were killing them. “We have to be smart and keep our energy for when the clock is ticking, not for the scrums and the fights. We can’t worry about out-toughing them.”

In the third game, Toronto came out flying and banging bodies. With a little more room to operate and the advantage of the last line change, Gilmour and Andreychuk cranked up production. Although the Leafs wasted three consecutive first-period power plays, the extra-man situations gave them the momentum needed to jump into a 2–0 lead. But it was Clark who silenced his critics with a commanding, muscular performance. Several Wings were nearly quartered by his bone-crunching Clarkian body slams. He scored the goal that gave Toronto a 3–1 lead—parked at the edge of the crease, taking a pass from Gilmour behind the net and stuffing a backhand between the legs of Tim Cheveldae—and shoved the Leafs back into the series, Toronto winning 4–2. In the locker room afterwards, the unassuming warrior made a press pack wait for twenty minutes while he had a long chat with a young fan in a wheelchair. Then Clark stood in the media circle, braces still latched around both gimpy knees, and offered only a gentle retort. “You know the media is going to throw things at you. I just put my skates on, play the game.”

Burns spread around the praise. “The fans were just great. The guys on the bench were just jumping. It was the first time I’ve seen everybody on the bench just jumping.” A series of tactical coaching moves had contributed significantly. Using last line change to his advantage, Burns deployed ten different line combinations in the first period alone. “And be sure to leave Dino Ciccarelli alone in front of the net. Why get into a wrestling match with him?” The pest was not a factor. “It took us two games to get used to playoff-style hockey, but we’re in control of our emotions now and we still don’t feel like we’ve played our best hockey.”

The yapping between opposing coaches, each trying to secure a psychological edge, was bordering on silly. Murray even whined that Burns had a leg-up because of the eight-inch riser behind the Leaf bench. He complained that it gave Burns a better view and made him more imposing to game officials. Burns sniped right back, noting that the visiting coach’s office in Detroit was in the men’s washroom. “That’s not bad, except when a security guard came in to use it. The place smelled for half an hour.” By the start of game four, Murray had his own riser.

It was another chippy affair. While Gilmour and Andreychuk performed superbly, it was the supporting players who stepped up, Burns issuing kudos in particular to his ferocious checking line of Peter Zezel, Mark Osborne and Bill Berg for containing Detroit’s top troika. Zezel won three crucial faceoffs in the Leaf zone with a minute left in regulation, goalie pulled, Toronto up 3–2. Raised in Toronto’s Beaches neighbourhood, Zezel spoke reverently about donning the blue and white. “Every time the sweater is put on, there’s a price. As soon as that sweater goes on, guys go for their guns.”

With the series tied at two games apiece, Burns was jubilant. “It could have been the hardest I’ve seen them work. There is a lot of pride on this team.” Andreychuk had potted the winner and was asked if he’d finally shed the “Andy-choke” handle. “Not by any means. I’ve still got a long ways to go.” Little did he know.

Everybody was banged up and bruised, none more than Gilmour, with several stitches threaded to close an inch-long cut below one eye and a crescent-shaped cut above the other eyebrow. That owwie occurred when Steve Chiasson drove Gilmour’s head into the boards in the second period. Later in the game, Mark Howe tomahawked his left wrist, at the base of the thumb, sending Gilmour straight to the Gardens medical clinic cupping the hinge, Dr. Leith Douglas in pursuit. He returned to action a minute later, taped up. “Your heart stops,” said Burns. “But he’s tough. He came back.” No worries, said Gilmour, the wrist wasn’t broken. “I’ve got X-ray eyes, so I can tell you it’s only a bruise.”

“It’s a new series now,” Burns crowed. “That’s what happens in the playoffs. Things go from hot to cold and from cold to hot. That’s the fun of the playoffs, what makes it exciting. This could be a long series. We’re an ugly team to play against.” There were smiles of delight, too, when, contrary to predictions, Borschevsky suddenly returned to practice. Gilmour assured inquisitors his wrist wasn’t busted, even joked about doing pushups and lifting weights. Stepping off the ice after practice, he feigned a severe limp. There were serious concerns, however, about what the hard-smashing series was costing Gilmour. Burns was constantly double-shifting his go- to guy and Gilmour’s weight was dropping dramatically, despite all the pasta carbs he was ingesting. “After games, they just laid me down on a table and threw IVs at me,” Gilmour recalls. “With all those electrolytes, I’d walk out of there feeling like I hadn’t even played a game. Then I’d walk home. At the time, I was living right next to the Gardens on Wood Street, so it was a short walk.”

Returning to the mosh pit of the Joe, Toronto purloined a game they probably had no right winning, overcoming a 4–1 deficit. They exploited Detroit’s weak link in goal, beating Cheveldae twice on long shots by Dave Ellett. A fluke goal by Clark midway through the third sent it into overtime. Hero of the night was Mike Foligno, who’d begun his NHL career as a Wing. Clark dug the puck out from a scramble at the left boards and passed to Foligno, who fired a shot through a maze of bodies from between the circles, winning the game 5–4. Then he executed his joyful victory hop, jumping so high in the air his knees almost touched his chin.

“It was jubilation on a number of counts,” says Foligno. “One, obviously, was that I hadn’t even known at the start of the season if I was going to be able to come back and play again. Two, I used to play for Detroit and felt like I had some unfinished business there. And then, to have scored that overtime goal, oh man. I remember Wendel’s work on the wall and Mike Krushelnyski’s screen in front of the net. When I scored, I threw off my gloves. It’s funny; I don’t even know why I did that. Then a whole bunch of other guys threw their gloves in the air, Todd Gill and Peter Zezel. Oh my God, it was like a Stanley Cup championship game. There was so much emotion. Everybody was happy we’d won the game, but I think the guys were happy for me as well. It had been such a tough grind I’d gone through. That win in overtime was so much fun. And you know what? The feeling we had that night, we wanted to get it again. That’s when we really got a taste of winning, for the feel of winning, and wanted to taste it again.” Burns was thrilled for Foligno. “The old guy bopped one in for us.” In overtime—and there would be many more OTs to come that spring—Burns had unshakeable confidence in his players, harking back to the harsh workouts he’d put them through in practices throughout the year. After one such gruelling session, he’d barked: “There’ll be a night next April, in overtime, when the work we do now will pay off for us.”

The Red Wings were aghast. Toronto had put itself in a position to clinch at home in game six. The city, gaga with hockey fever, welcomed the Leafs back with full-throated gusto at the usually mausoleum-hushed Gardens. But they left the arena in distress. “We got our asses kicked,” says Gilmour. Surrendering five unanswered goals in the second period—two of them shorthanded—Toronto was drubbed 7–3. At the start of the third frame, Burns replaced Potvin with Daren Puppa. “He told me on the bench, ‘Just take a break, because you’re going back in for game seven,’ ” says Potvin. “That showed he still had confidence in me.” Burns could find little that was positive to seize on in the rout. “We can’t be any worse than we were tonight. That’s the only good thing.” A concussed Zezel left the building leaning on his father, Ivan, with instructions that he be awakened every two hours. Reporters took to their computers, chiselling a headstone in advance for the Maple Leafs. Burns shielded his players. “A lot of experts around here said we’d be out in six and we’re still here.” He did reclaim the underdog stance that was always a favourite posture, telling the players: “Nobody believes in us. It’s poor little us against the world. However, you men can show them all how wrong they are. It all comes down to determination and desire.”

Who would have bet on the Leafs at that point? They’d stolen one in Detroit, but to do it again, in a game seven? Dream on.

“We were still learning how to win in the playoffs as a team,” Foligno says. “Detroit had come back with barrels a-blazing in our building. I remember us getting scared but saying, ‘You know what? We’ve still got a chance here.’ Pat warned us we might not have the lead to start in game seven, but ‘Let’s learn from our last game, don’t quit no matter what the score is.’ And we did learn. We let them get the lead [in the second period] and we battled back and we were able to take the game into overtime again, and the rest is history.”

Burns had pulled out all the clichés: backs against the wall, do-or-die, no tomorrow, when the going gets tough … Yet it was the Wings who looked more tightly wound, nursing a one-goal lead through half the game. Before the third frame, Burns addressed his troops, keeping the pep talk short and focused. “It’s there for you, guys.” In the third, Detroit was up 3–2 after an exchange of goals. With just two minutes and forty-three seconds left in regulation time, Clark pounced on a loose puck in the corner and passed to Gilmour in the slot, who beat Cheveldae to even the score, sending the game into overtime. “All of a sudden, boom-boom-boom, we were back in it,” says Gilmour. “When I tied it, I felt in that moment, the pressure hit Detroit.”

During the OT intermission, in the corridor outside the dressing room, Burns smacked his palms together. “I love this. This is the kind of hockey I get off on. This is great!” What he told the players was, “Just throw everything at the net.” In fact, Toronto mustered only two shots in OT, but Borschevsky—“Nik the Stick” to his teammates—made one of them count. Gilmour, who’d been centring Andreychuk and Glenn Anderson, had just got back to the bench with his wingers. Burns turned him right around, sending him out again with Clark and Borschevsky. At 2:35, the little Russian with the broken orbital bone who’d not been expected to heal quickly enough to rejoin the series, wearing a plastic shield, redirected Bob Rouse’s goalmouth pass, stabbing home the winner. Yowza.

As the Leafs swarmed over Borschevsky, jumping and dancing in an orgy of celebration, Burns and assistant Mike Murphy shared a bear hug. Up in the press box, Cliff Fletcher buried his face in his hands. Then Burns turned and pointed to Fletcher with an outstretched arm. “Except for that first game back in Montreal, that was the most emotional I’ve ever seen Burnsie,” says Gilmour.

In the dressing room afterwards, Borschevsky was besieged by reporters. “The doctors told me ten days. But I say I play today.” Then he raised his arms in surrender. “I’m sorry. I no speak good English. Maybe tomorrow I talk better.” In another corner, Todd Gill wept tears of joy. Burns, making his way to the interview podium, got in one zing: “So much for the experts.” He said the win was “almost like an apology to our fans” for game six. “For the past few days, I’ve been telling everyone who would listen that this series would go seven games and that we’d win it in overtime. Of course, I also said that Glenn Anderson would score the goal.”

Changed into street clothes, the Leafs straggled towards the bus that would take them to Windsor, across the Detroit River, and the flight home. Wendel Clark carried a case of beer under each arm.

Bring on the St. Louis Blues … and all that jazz.

With Detroit relegated to postseason footnote, the Norris Division final loomed as the Tale of the Cat and the Dog: Félix and Cujo. For his part, Burns was annoyed to be denied the underdog role, even as he pointed to such big-game St. Louis horses as Brett Hull and Brendan Shanahan. Toronto held a 4–0–3 edge in regular-season play, but Curtis Joseph, from Keswick, Ontario, held the hotter hand, standing on his head when the Blues swept Chicago. Solving the Cujo riddle was now Toronto’s challenge. Burns allowed the Leafs one optional practice before the series opened at Maple Leaf Gardens, but otherwise granted them no rest to savour the Detroit triumph. “He didn’t give us a chance to breathe and enjoy the win because he said we hadn’t achieved anything yet,” says Gill. “To be fair to Pat, he was hard on everybody. Usually, your best players get away with a little bit. One thing I loved about Pat is that he was as hard on Dougie as he was on the rest of us.” (At the time of this conversation, nineteen years later, Gill was coaching the Kingston Frontenacs, the junior team managed by Gilmour.)

Joseph was allegedly vulnerable high to the glove side, but he held the Leafs off the scoreboard in game one until there was under a minute left in the first period, John Cullen tucking in his own rebound. Philippe Bozon got that one back midway through the third. And there the score remained for what seemed an eternity. Back and forth the teams swung in what the advance billing had conjectured would be a dull, defensive goaltending duel. There was nothing boring about the battle between net men. Not until 3:16 of the second overtime, as the clock approached midnight, threatening to turn the TV broadcast into Hockey Morning in Canada, after Joseph had faced sixty-two shots and been clunked on the head by Foligno’s skate, did Gilmour, the former Blue—hero one more time, with gusts to legend-in-the-making—prick the cocoon of apparent invulnerability. Every other Leaf was tied up by frantic checkers when Gilmour darted out from behind the net with a swirling, spinning, dizzying wraparound goal that confounded Joseph. “It was the longest game I’ve ever played,” says Gilmour, who’d skated miles, logging Herculean ice time.

With the pounds still falling off, he looked emaciated, sometimes seeming no more than a black-and-blue smudge inside a jersey. “I should take that little runt home and force-feed him,” joked Burns.

The perspiration had barely dried off when the puck dropped on game two, the Gardens a sweat-soaked sauna. With no air conditioning, muggy air clashed with cold ice surface, creating a misty fug at ice level. Potvin knew he had to match Joseph save for save; there was clearly no margin for error in this showdown. “It was tough because I knew I couldn’t let anything get by me. But at the same time it was fun. Because Curtis was so good at the other end, I knew I had to be equally good. And honestly, I grew up a lot from the first series against Detroit. Now it was about taking care of business.”

Hull scored on the Blues’ third shot of the game, stunning the crowd. But Gilmour, quickly ascending to the ranks of the immortals, made it 1–1, scooting in from the corner to stuff the puck behind Joseph. Garth Butcher, St. Louis defenceman, immediately and sharply—almost quicker than the eye could see—scooped the disc out of the net. The episode went to video review, scrutinized from several angles, before referee Paul Stewart, after an interminable wait, signalled it was a good goal. In the next frame, Gilmour was clipped in the face with a high stick. He fell to the ice, writhing, and the partisan crowd held its breath. Finally, he stood up again, gave Stewart an earful for not calling a penalty, and the game proceeded.

Again there was no further scoring in regulation. Again, it went to overtime. Again, it went to a second overtime. Again, Joseph withstood a Leaf barrage. Again it would be a 2–1 verdict, but this time for the Blues. At 3:03 of the fifth period, St. Louis defenceman Jeff Brown pounced on a rebound and hit the open side of the net, Potvin down. Through six playoff games, including the opening round against the Blackhawks, Joseph had now stopped 252 of 261 shots. His jackknife splits and Venus-flytrap glove snaps were jaw-dropping. “He’s playing right now as if he was four hundred pounds and four feet wide,” said Burns. As the series switched to St. Louis, the coach had little advice to impart. “Put the puck in the net more, that’s all I can say.” Despite hammering Joseph with 121 shots, the Leafs left Toronto with no better than a split in the series.

Looking to change the dynamics, Burns decided to dress the sparsely used Mike Krushelnyski for only his third outing of the postseason. The veteran had enjoyed a splendid first half of the season, but then went frigidly cold. Still, he was the only Leaf to play in all eighty-four regular-season games that year, albeit with reduced ice time. “Fifty-two players had come and gone through the door that season,” Krushelnyski recalls. “That’s tremendously hard on a coach, juggling players and trying to fit in all the pieces.” What sticks out in his memory is one especially punishing practice. “We’d lost the night before, and Pat bag-skated us for forty minutes. If he’d have gone even one more minute, there would probably have been a huge revolt. But Pat wasn’t there to be our best friend. At times you loved him, and at times you hated him.”

Wendel Clark scoffs at the notion of either/or. “The whole thing with a coach isn’t whether you love him or hate him. It’s whether you respect him. Pat had a lot of respect.”

Game three was mercifully shorter, but no sweeter for Toronto, a 2–0 lead vanishing into a 4–3 loss. Gilmour had a new track of stitches across the bridge of his nose, but a St. Louis columnist had more fun mocking Burns’s signature pompadour. “What’s the deal with coach Pat Burns? Why has this beefy, tough-guy former cop made himself over to look like oily lounge singer Wayne Newton?”

Alarm began to creep up the Leafs’ spines. “Fear is knocking on our door, and the way we have to answer it is with faith,” said Foligno. “We’ve got to believe in each other. I know we do.” Then he lightened up the mood. “As a team, our goal, our whole reason for being here, our very existence, is to try to put a smile on the face of Pat Burns. And we’ve actually done that a few times this season. But we want to do it some more.” Burns, grimacing, was simply sick of listening to encomiums for Curtis Joseph. “It’s been Joseph, Joseph and more Joseph. We finally got three goals against him, but the trouble was we gave up four.”

In the game four matinee, Toronto exposed Joseph as merely human. Leafs crashed his crease, threw him off balance, Foligno and Krushelnyski creating most of the traffic. “They’ve given us good hockey all year,” said Burns of his two inelegant but useful marauders. “They played the style we wanted: move your legs, take a punch in the face.” Joseph yowled to the referee about the liberties Toronto was taking with his turf. The ref had a word with Burns. “We’re just bringing the puck to the net,” he responded, angelically. “That’s our job.” Roused by a Burns pre-game speech, the players threw their bodies around with purpose in the 4–1 victory. A sizzling Potvin, who’d sweated off nine pounds of water in the game, outplayed his St. Louis counterpart.

As the series reverted to Toronto, the two teams had developed a serious hate-on for each other. Except for tree-hugging Glenn Anderson. “Hatred isn’t in my vocabulary,” he sniffed.

In the fifth game, Toronto continued its domination, outchecking, outscoring and outsmarting the Blues, clobbering them 5–1. A win in the sixth game, at decrepit St. Louis Arena, would give the Leafs their first Norris Division title since moving from the Adams in 1981 and send them to the Campbell Conference final. Back in the Gateway City, the temperature was scorching. Foligno, warning that the Blues would not roll over, inverted a cliché with a spoonerism. “We’ve got to make sure we hold our heads, uh, our feet, on the ground.” Burns found time to tweak his opposite number, St. Louis coach Bob Berry, who’d been going through agonizing withdrawal as he tried to kick the smoking habit. The Toronto coach sent over the obligatory lineup sheet to the Blues dressing room with a cigarette taped to it.

Inside the muggy barn, Burns’s pompadour was wilting as he pounded his beat behind the bench. With Toronto leading 1–0, watching his players dilly-dally as if victory were assured, his hair practically stood on end. “I could feel it when we left Toronto. There was all this talk about Stanley Cup, Joe-Sieve [the moniker hung on Joseph by Leaf fans], stuff like that. You can’t talk like that in the playoffs.”

The Blues prevailed 2–1, and now the situation was reminiscent of Toronto’s previous series against Detroit, when the Leafs had failed to put the Wings away in six, inviting the excruciating tension of a deciding game seven. Afforded the chance between the smooth and bumpy road, the Leafs again opted for the latter. “We played with fire and we got burned,” the coach sighed. “We’ve really put gas on the fire now.”

Foligno admits the Leafs felt a sense of foreboding going into St. Louis. “They had so much pride, the Blues. They didn’t want to lose in front of their home fans. So that’s what we told ourselves after. But when we got back home, there was absolutely no way they were going to beat us in our own building. We were convinced we would raise our level in the next game to the point that all our passes were going to be on the tape, everything would be executed properly, and that’s exactly how it turned out. It was unbelievable; we played the game that mentally we’d seen ourselves playing.”

Still, staring down another game seven, Burns was fretful. “There’s no doubt about it, the visiting team has the advantage. The pressure’s on us. I’ve told them to go find themselves a way to put on the jersey at 7:20 and say, ‘This might be the last time I put it on.’ Seventh games don’t come down to tactics. They come down to what you have within you. They’ve got to reach deep into their hearts and understand what this means.” Gilmour deadpanned: “Pressure? What pressure?”

Who could have foreseen what would befall the Blues that night at Maple Leaf Gardens? Curtis Joseph, like Icarus, must have flown too close to the sun. He melted. Wendel Clark scored two goals and ripped Joseph’s mask off on another bazooka slapshot that struck the goalie flush on the mug. Four goals in the first period took all the starch out of St. Louis in a 6–0 defeat. All Gilmour did was pick up a goal and two assists, to give him 22 points in the postseason, surpassing Darryl Sittler’s club record of 21. Game, set, match. “Pat had us so prepared for that game,” he says. “He didn’t do it with a lot of loud speeches, either. He just spoke to us quietly.”

Outside, the city went crazy, a good crazy. Foligno, who lived downtown near the Sutton Place Hotel, waded through the crowd as he walked home, weaving through the impromptu parade on Yonge Street. “I always tell people that I’ve been to a few victory parades in my life. There was one in Colorado, when we won the Stanley Cup. There was the one when the Blue Jays won the World Series. And there was the one after our series against St. Louis. I had a bunch of family in town and they joined the parade. I remember walking down the alleyways to get to my house because I could not walk down the street without being mobbed. It was amazing.”

A late arrival: baby Patrick with his parents Alfred and Louise and (clockwise from top left) siblings Lillian, Sonny (Alfred Jr.), Violet, Diane and Phyllis. (photo credit 12.1)

The former homicide cop joins the Montreal Canadiens: At the conclusion of the 1987–88 season, the scandalously carousing team was in need of a man like Pat Burns. (photo credit 12.2)

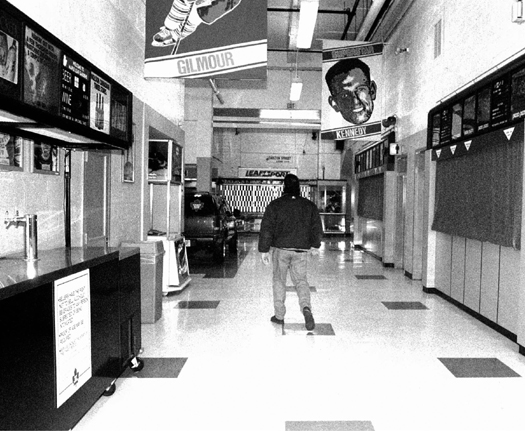

Renewing the Leafs, 1992: He told the players to hang up their jerseys carefully after each match. Mike Foligno recalls: “Even something as small as that, never letting … the logo touch the ground, was about bringing back pride in the club.” (photo credit 12.3)

Playing a part, 1993: While coaching in the NHL was a dream come wildly true, Burns had other fantasies—guitar picker, cowboy, Hells Angel—and often dressed the part. (photo credit 12.4)

Facing an uncertain future: As the 1995–96 season got under way, few observers could have predicted that Burns’s shelf life in Toronto was ticking down rapidly. (photo credit 12.5)

NHL Finals, 2003: At last, with the New Jersey Devils, he’d won the only silver hardware that matters. “My son Jason and my daughter Maureen came in from Montreal.… My wife was there, friends and family from Quebec. I pointed the Cup at them because sometimes you forget the people who are behind you, who were there when things don’t go so good.” (photo credit 12.6)

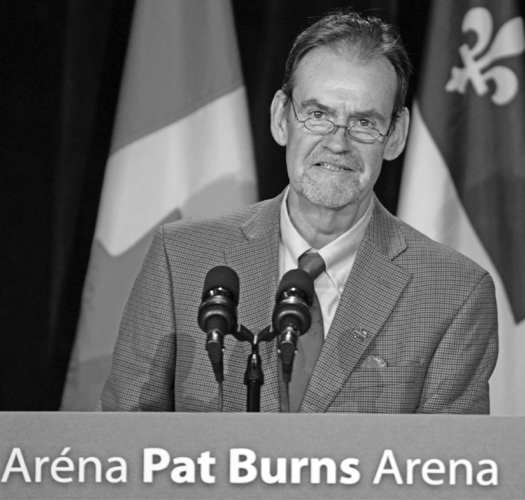

“I know my life is nearing the end, and I accept that”: At the news conference in March 2010, where it was announced that an arena would be named after him in Stanstead, Quebec. (photo credit 12.7)

Line Burns carries her husband’s ashes: The Stanley Cup urn was requested by Pat, who had also asked for a small funeral, conducted by a parish priest. What he got was a grand affair fit for a statesman. (photo credit 12.8)