‘I have volunteered for the Sturmstaffel of my own free will. I fully understand the fundamental principles of the Staffel.

1. All attacks will, without exception, be carried out in formation and to within the closest possible range of the enemy.

2. Losses suffered during the approach will be compensated for by immediately closing up on the formation leader.

3. The enemy under attack is to be shot down from the shortest range possible or, if this is unsuccessful, destroyed by ramming.

4. The Sturm pilot will remain in contact with the stricken enemy until the point of impact with the ground has been established.

‘I voluntarily accept the obligation to abide by these principles, and will not return to base without having destroyed my enemy. Should I violate these principles, I am prepared to face court martial or dismissal from the Staffel.’

When the first dozen or so volunteer pilots put their signatures to this extraordinary document on 17 November 1943, they were opening a new chapter in the long-running story of the daylight defence of Hitler’s Reich.

That story had begun more than four years earlier with the first tentative attacks across the North Sea by machines of RAF Bomber Command. These initial incursions had been given short shrift by the Luftwaffe’s fighter defences. Of the 34 Wellingtons despatched against naval targets on the two raids of 14 and 18 December 1939, exactly half had been shot down – and this without their even penetrating the German mainland (see Osprey Aircraft of the Aces 11 – Bf 109D/E Aces 1939–41 for further details)! Little wonder, therefore, that the British quickly reconsidered their strategic policy and henceforth restricted the RAF’s bombing campaign against Germany primarily to the hours of darkness.

It was America’s entry into the war two years later which rekindled the spark of daylight bombing. Confident in the power of their four-engined B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators, and of their reputed ability to ‘place a bomb in a pickle barrel’, the USAAF was wholly committed to daylight precision bombing. The Americans resisted all attempts to persuade them to add their numbers to the loose streams of RAF bombers now raiding Germany almost nightly. They would instead adhere rigidly to their tight daylight formations.

In time, these two diametrically opposed national policies would combine to form the ‘round-the-clock’ bombing offensive, the British by night and the Americans by day. But this was still a long way off. It was a good six months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on the morning of 7 December 1941 that the first USAAF bomber crews were sent across the English Channel in borrowed RAF twin-engined Douglas Bostons to attack targets in occupied Europe; and it was another six months before the first USAAF four-engined ‘heavies’ dropped their bombs on Germany proper.

The target of the Americans’ historic daylight raid of 27 January 1943 was the North Sea naval port of Wilhelmshaven – protected by the same hornet’s nest of defending fighters that had mauled the RAF’s Wellingtons so savagely back in December 1939. This time only one of the 55-strong attacking force of B-17s was brought down (although 32 more suffered damage to varying degrees).

It seemed at first as if the USAAF’s faith in the ability of compact bomber formations to protect themselves against fighter attack had been fully vindicated. It was not until the Fortresses and Liberators started to venture deeper into Germany’s heartland, beyond the range of the escort fighters then available, that their losses began to assume alarming proportions. These culminated in the twin attacks on Schweinfurt and Regensburg on 17 August 1943, when no fewer than 60 B-17s were brought down and nearly three times that number damaged.

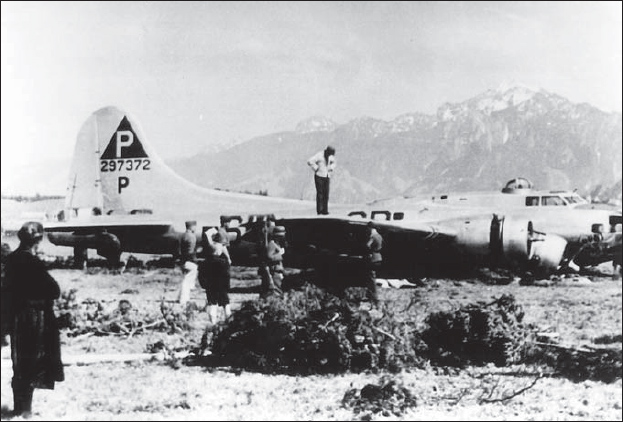

The Eighth Air Force paid heavily for its early unescorted raids deep into Germany. The 100th BG’s B-17F ALICE FROM DALLAS was just one of 60 Flying Fortresses lost on the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission of 17 August 1943

A second strike against Schweinfurt less than two months later cost another 60 Fortresses, plus a further 145 damaged. Casualty rates such as these – approaching 25 per cent – meant that the daylight battle for the Reich still hung very much in the balance. The Luftwaffe’s fighter and flak defences were demonstrating that, deep inside German airspace, US ‘heavies’ were almost as vulnerable as Bomber Command’s twin-engined types had been when attacking the outer edges of Hitler’s domain four years previously.

But while Dr Josef Goebbels propaganda ministry was gleefully trumpeting the news of each success in the air, cooler and more professional minds could already appreciate the inherent danger posed by the Eighth Air Force’s steadily growing strength. Even before second Schweinfurt, one relatively junior Luftwaffe officer realised, with remarkable prescience, that the Americans’ inexorable build-up of power had to be disrupted before it became overwhelming – and that such disruption could only be achieved by radical measures.

The son of an army general, Hans-Günter von Kornatzki had been born in Liegnitz, Lower Silesia, on 22 June 1906. He joined the Reichswehr (inter-war German army) aged 21, and subsequently volunteered for flying training. Graduating from the Jagdschule Werneuchen in the spring of 1934, his first posting was as adjutant to I./JG 132 – the premier, and, at that time, only Jagdgruppe in the then still covert Luftwaffe. The following year Oberleutnant von Kornatzki was transferred to the newly forming II./JG 132. Promoted to hauptmann in 1936, he was given command of one of five ad hoc ground-attack units set up at the time of the Munich crisis (see Osprey Elite Units 13 – Luftwaffe Schlachtgruppen).

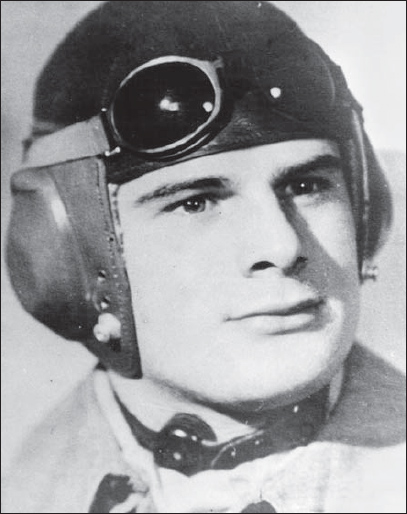

The man who saw the writing on the wall, Major Hans-Günter von Kornatzki was the ‘Father of the Sturm Idea’

Although the outbreak of war found Hauptmann von Kornatzki tasked with establishing new Bf 109-equipped Jagdgruppe II./JG 52 (see Osprey Elite Units 15 - Jagdgeschwader 52 for further details), it was only a matter of weeks before he took up the first of a series of staff appointments. These would ultimately lead to his joining the staff of the General der Jagdflieger, Generalmajor Adolf Galland, on 24 September 1943.

By now having himself risen to the rank of major, von Kornatzki knew Galland of old, and lost little time in outlining his revolutionary proposals to the General der Jagdflieger. He conceded that Luftwaffe fighter units presently operating in the defence of the Reich were exacting a steady, and at times enormous, toll on the US ‘heavies’. But what was really needed, he argued, was one major blow, or a series of major blows, designed to knock whole bomber formations out of the sky. Kornatzki believed that the Americans would be unable to ignore such losses, thus placing their entire daylight bombing strategy in jeopardy.

The best way to achieve the desired result, von Kornatzki continued, would be by creating units of ‘specially trained volunteers, flying heavily armed and armoured fighters, who would be willing to get in close to the enemy, in tight formation, before opening massed fire at the shortest possible range, and who – if all else failed – would be prepared to ram their opponents’. Galland was reportedly taken by the idea and immediately authorised von Kornatzki to set up an experimental Staffel of what he termed Rammjäger.

Early in October 1943 officers toured fighter bases and schools in Germany and the occupied territories calling for volunteers. Although the response was not overwhelming, more than the required number came forward to form a single Staffel.

Major von Kornatzki interviewed each of the prospective candidates in his Berlin office. He explained the principles behind the unit’s formation and spelled out what would be expected of its members. While not playing down the risks involved, he stressed that the Staffel was not a suicide unit (the term ‘kamikaze’ had not yet entered common usage). Ramming would only be used as a last resort, and then not as a deliberate act of self-immolation. Rather, the pilot would be expected to aim his heavily armoured fighter at the bomber’s relatively vulnerable tail unit. The loss of, or even severe damage to, the enemy bomber’s tail control surfaces would almost certainly result in its going down, while the attacker stood every chance of survival in his armour-encased cockpit.

Kornatzki likened his Staffel to the infantry’s Sturmtruppen, or shock-troops – small detachments that went in ahead of the main attack to break up and demoralise the enemy. This was exactly the role he envisaged for his fighters – to blow a huge hole in the tight phalanx of bombers, causing chaos and confusion among the rigidly structured boxes, thus making them an easier target for the Jagdgruppen following in their wake.

The analogy obviously struck a chord in official circles too, as witness this entry in the war diary of I. Jagdkorps, dated 19 October 1943;

‘With immediate effect, Sturmstaffel 1 to be activated via the proper channels for a provisionary period of six months.’

The 16 pilots (some sources list 18 names) selected by Major von Kornatzki at the Berlin interviews were ordered to report to Achmer airfield, near Osnabrück. They were a mixed bunch – combat veterans from both bomber and fighter units, flying instructors and newly qualified trainees. Their reasons for volunteering for the Staffel were as varied as their backgrounds. A similar number would join in the weeks to come, bringing Sturmstaffel 1’s full pilot roster up to some three-dozen.

Among the latter arriving at Achmer in early November was the recently promoted Major Erwin Bacsila. Only four years younger than von Kornatzki, Bacsila had been born in Budapest in 1910 in the days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After graduating from the Austrian military academy between the wars, he subsequently joined Austria’s fledgling air arm. Upon the Anschluss (annexation of Austria by Germany), Bacsila was transferred to the Luftwaffe. The outbreak of war found him as an oberleutnant serving in the Polish campaign with the Bf 109-equipped II./ZG 1 (JGr. 101).

Major von Kornatzki was ably assisted in setting up the first experimental Sturm unit by fighter pilot Major Erwin Bacsila

Unlike von Kornatzki, Bacsila would remain on operations (despite his advancing years), subsequently flying with both JGs 52 and 77 in Russia and North Africa. Shortly after his 14th victory of the war (a Spitfire claimed over Agedabia on 13 December 1942), Hauptmann Bacsila was brought down behind enemy lines by British anti-aircraft fire, but he was able to make his way back to friendly territory on foot.

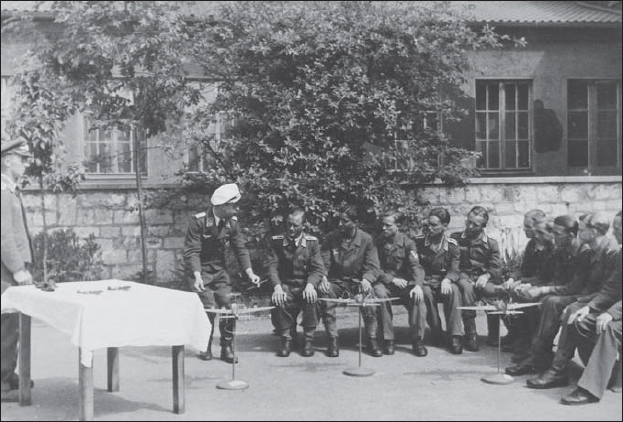

The Luftwaffe’s usual training of pilots for defence of the Reich duties was at times rudimentary in the extreme. Here, a white-capped oberleutnant uses models to demonstrate a frontal attack on a trio of Fortresses. So much for theory . . .

Following the evacuation of Tunisia, Erwin Bacsila returned to the Russian front, and it was from here that he volunteered his services for Sturmstaffel 1. His maturity and wealth of operational experience made him the ideal right-hand man for von Kornatzki as, together, the two majors set about the task of preparing the volunteers for what lay ahead.

Achmer proved to be the perfect location for the job, as the test field, situated some 7.5 miles (12 km) north-west of Osnabrück, played an important role in the development of Luftwaffe aircraft and weaponry during the war. Twelve months hence it would be home to the Messerschmitt Me 262s of the famous Kommando Nowotny (see Osprey Aircraft of the Aces 17 – German Jet Aces of World War 2).

. . . the reality was somewhat different. Here 92nd BG B-17s parade majestically across the sky, while escorting fighters keep watch overhead

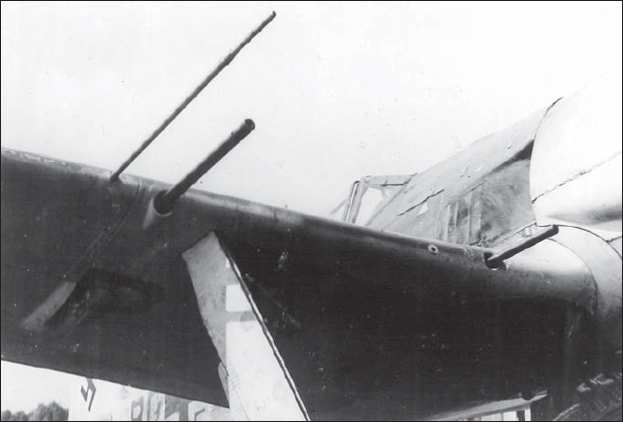

The two starboard 20 mm MG 151/20 wing cannon of a standard Fw 190A-6

Among the current occupants was Erprobungskommando 25. This experimental unit’s remit was the ‘development and testing of special weapons to combat four-engined bombers’. Surrounded by cannon-armed Bf 110s and Me 410s, plus Bf 109s equipped with underwing rocket tubes, the pilots of Sturmstaffel 1 could not have been in better company.

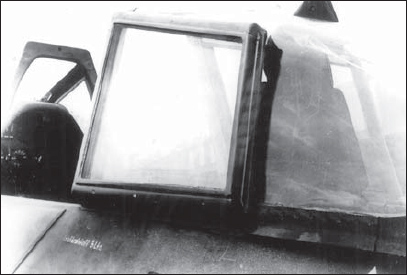

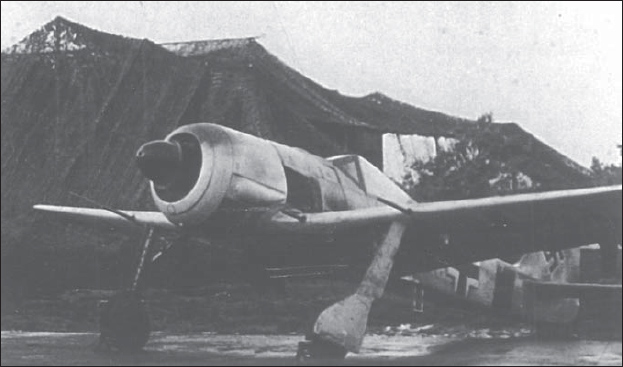

As well as the chamfered-edge slab of external armour plate (just visible at lower left), early Sturm machines were fitted with 30 mm armoured glass panels on either side of the cockpit canopy. But these ‘blinkers’ (or ‘blinders’), as they quickly became known, were not universally popular. They severely restricted lateral vision, and many pilots had them removed

Their own aircraft arrived in the shape of a dozen Focke-Wulf Fw 190A-6s. These were apparently standard six-gun models (two fuselage-mounted 7.9 mm MG 17 machine guns and four 20 mm MG 151/20 wing cannon) which the Staffel – with the help of Focke-Wulf technicians but, allegedly, without the prior knowledge or approval of the General der Jagdflieger – proceeded to modify by adding 30 mm ‘Thorax’ armoured glass to the windscreen quarterlights and 5 mm thick external armour plating to the sides of the cockpit.

A further refinement was the fitting of 30 mm armoured glass panels (in fairly primitive wooden frames) to either side of the sliding cockpit canopy. Quickly dubbed ‘blinkers’ (or ‘blinders’), these panels were not universally popular. As their nickname implies, their presence seriously impaired the excellent all-round visibility for which the Fw 190 was renowned, and the problem only became worse at altitude when ice quickly built up between the panes and obscured lateral vision altogether!

Designed to protect the pilot from 0.5-in (12.7 mm) machine gun fire (the calibre of the Brownings which constituted the US ‘heavies’’ defensive armament), the conspicuous slabs of armoured glass and steel plate were said to be good for morale. But many pilots preferred to take their chances, willingly sacrificing the extra protection for unrestricted visibility by having the ‘blinkers’ removed from their machines.

Unteroffizier Werner Peinemann of Sturmstaffel 1 sits in the cockpit of his Fw 190, whilst a mechanic rests on the 50 mm plate of strengthened frontal-plate glass. This aircraft also has 30 mm armoured glass quarter and side panels. Wounded in action on 4 March 1944, Peinemann joined 11./JG 3 upon his recovery two months later. He then transferred to 7.(Sturm)/JG 4 on 21 August 1944 and was killed when his fighter crashed on take-off on 28 September. Peinemann had a solitary victory credit to his name at the time of his death

The closing weeks of 1943 were spent allowing pilots to get the ‘feel’ of their new mounts. The added weight of armour had a marked effect on the performance of the A-6, or Sturmjäger, as it was dubbed. As a result, the two fuselage machine guns were removed on most machines and the muzzle troughs faired over. Unsurprisingly, it was those members of Sturmstaffel 1 who had previously flown ops on fighters who were among the first to master the foibles of the heavyweight Focke-Wulfs, although as one put it, ‘I had my throttle arm through the firewall up to the elbow before I could persuade the beast even to leave the ground!’

On 17 November 1943 Luftwaffe C-in-C Hermann Göring, accompanied by General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland (left), paid an official visit to Achmer. After inspecting the ranks of Hauptmann Horst Geyer’s Ekdo 25 . . .

Soon, however, all pilots were proficient enough to start practising the tactics they were to employ in battle. Unlike the head-on attacks pioneered by JG 2 (see Osprey Aviation Elite Units 1 – Jagdgeschwader 2 ‘Richthofen’ for further details) when tackling US bombers over France in 1942 – the infamous ‘twelve-o-clock-high’ interception – von Kornatzki’s plan was for the Staffel, flying in close arrowhead formation, to approach the enemy bombers from directly astern. The additional armour bolted to their aircraft would offer them some protection from the defensive fire that the bombers’ tail, ball, waist and upper gunners would undoubtedly be throwing at them. But there was another hazard.

If an action were to take place within enemy fighter range, the cumbersome Sturmjäger – in precise formation, sights set on the bombers they were overhauling – would themselves be wide open to attack. Under such circumstances the Staffel would need a high-altitude escort of its own to keep enemy fighters off its back.

. . . the Reichsmarschall turned his attention to the pilots of Sturmstaffel 1. Here, he chats to Staffelkapitän Major Hans-Günter von Kornatzki

It was during this working up, on 17 November 1943, that Luftwaffe C-in-C Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring paid a visit of inspection to Achmer in the company of General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland and a whole retinue of high-ranking officers (including former fighter Experten Hannes Trautloft and Günther Lützow, both now serving on Galland’s staff). This was the occasion on which the affidavit quoted at the head of the chapter was duly signed by the assembled pilots of Sturmstaffel 1. Underlining the seriousness of their undertaking, each pilot was asked to append his last will and testament to the said document!

With his hand upon von Kornatzki’s shoulder, Göring wishes him and his Staffel every success. On the Kapitän’s left are Major Bacsila, Oberleutnant Ottmar Zehart and Leutnant Hans-Georg Elser. Note the extensive use of camouflage netting to disguise the buildings in the background

At the beginning of January 1944 Sturmstaffel 1 was declared combat ready. The unit was transferred down to Dortmund, in the Ruhr, which was also the base of Major Rudolf-Emil Schnoor’s Fw 190-equipped I./JG 1, with whom the Staffel was were to operate. It did not have to wait long for things to start happening.

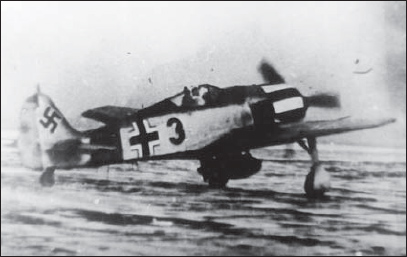

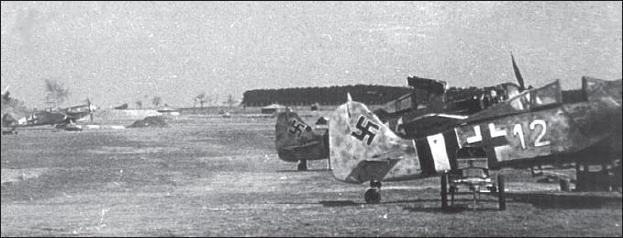

Early in January 1944, after completing working up, Sturmstaffel 1 transferred to Dortmund, home of I./JG 1. Trundling through the slush, this Gruppe’s ‘Black 3’ displays the unit’s flamboyant markings – black and white patterned engine cowling and red aft fuselage Defence of the Reich band

Initially, the Staffel’s Sturmjäger – here an ‘unblinkered’ example – also wore red aft fuselage bands. Like those at Achmer, Dortmund’s hangars were well camouflaged

On 5 January a force of 250 US ‘heavies’, escorted by P-38 and P-51 fighters, was despatched against the naval base of Kiel. Although both I./JG 1 and Sturmstaffel 1 were scrambled to intercept, only the former made contact. Carrying out their normal frontal attacks, Schnoor’s pilots claimed four B-17s for the loss of three of their own number. Failing to find the enemy, Sturmstaffel 1 pilots returned somewhat chastened to Dortmund to await their next opportunity. It came six days later.

A combat box of B-17s heads towards Germany

On 11 January 1944 an even larger force of Eighth Air Force bombers – 663 in all, with an escort of close on 600 fighters – was sent out against a number of aviation industry targets in central Germany. Aware of the developing threat, controllers had ordered I./JG 1 and Sturmstaffel 1 to move from Dortmund up to Rheine, close to the Dutch border, before 0900 hrs. Remaining there at readiness, the units received the order to scramble 90 minutes later. This time the pilots of the Sturmstaffel stayed in contact with the more experienced I./JG 1 until the enemy was sighted. Then, as the latter positioned themselves for their usual frontal assault, which netted them a trio of B-17s, the Sturmstaffel closed up into the tight arrowhead formation it had been practising for weeks past and began to approach another of the bomber boxes from astern.

The attack did not produce the hoped-for result. The box was not blasted apart by the massed fire of the Sturmjägers’ 20 mm cannon. In fact, just one Fortress was seen to go down. Even the victor, Oberleutnant Ottmar Zehart, admitted that his success owed more to luck than skill;

‘I just let fly at the formation of Viermots in front of me. That’s all.’

Nevertheless, the unlucky (and unfortunately anonymous) Boeing was a first, both for Oberleutnant Zehart – an ex-bomber pilot who had joined the Staffel the previous November – and for Sturmstaffel 1.

Austrian Oberleutnant Ottmar Zehart (centre), flanked here by Major Erwin Bacsila (left) and Leutnant Hans-Georg Elser (right), joined Sturmstaffel 1 in November 1943. Claiming the unit’s first victory (a B-17) on 11 January 1944, ex-bomber pilot Zehart subsequently destroyed two B-24s with IV./JG 3 prior to joining 7.(Sturm)/JG 4 as its Staffelkapitän. Doubling his score, Zehart had six victories to his credit by the time he was posted missing in action on 27 September 1944. Elser, who joined 3./JG 2 in the spring of 1944, was posted missing in action in the Ardennes (near St Vith) on 17 December 1944. Veteran fighter pilot Erwin Bacsila survived the war with 34 confirmed and eight unconfirmed victories to his credit. He passed away on 3 March 1982 in Vienna

There is, however, some evidence to suggest that the Staffel carried out a second attack over an hour later, and that two more pilots, Fähnrich Manfred Derp (ex-JG 26) and Feldwebel Gerhard Marburg, also claimed a B-17 apiece on this date. To complicate matters even further, it was Major Bacsila who was officially credited with Sturmstaffel 1’s first kill. The typed confirmation slip, issued by the RLM in Berlin and dated 9 June 1944, clearly states that the ‘Fortress II’ shot down by Bacsila on 30(!) January 1944 was the ‘first’ aerial victory of the Staffel’. In fact, neither von Kornatzki nor Bacsila flew many ops, and on these early missions the Staffel was usually led in the air by Leutnant Werner Gerth, who had previously been a member of III./JG 53 in Italy.

A line-up of fully armed and armoured A-6s shows off Sturmstaffel 1’s newly introduced and highly distinctive black-whiteblack aft fuselage bands

Some of the unit’s Sturmjäger also sported the Staffel badge

Whatever the true facts of 11 January, and whether they had lost one B-17 or three to the Sturmjäger, it would appear that the Americans remained blissfully unaware of the fact that they had been subjected to a revolutionary new method of attack.

There followed more than a fortnight of bad weather. With the Eighth Air Force restricting itself to operations mainly over France, the Staffel utilised the time to put in some more – demonstrably much needed – practice. Perhaps inspired by the striking black-and-white striped and checkerboard cowlings of I./JG 1’s Focke-Wulfs, it was around this time too that Sturmstaffel 1 adopted its distinctive black-and-white rear fuselage bands. A unit badge was also introduced, this consisting of a mailed fist clutching a stylised lightning bolt against a cloud background.

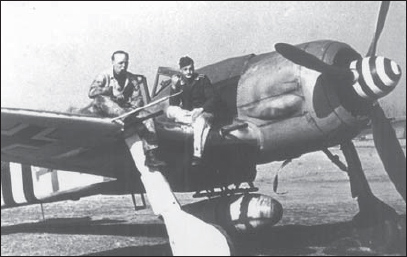

Major Erwin Bacsila (left) smiles for the camera with his Fw 190A-6 ‘White 7’ following the completion of an early Sturmstaffel 1 mission from Dortmund in mid-January 1944

After an abortive attempt to intercept a raid on Frankfurt on 29 January, I./JG 1 and the Sturmstaffel were sent up again 24 hours later, and this time contact was made. Sturmstaffel 1 closed in on a formation of B-24s which were part of a 150-strong force attacking Hannover. Two of the Liberators were brought down. Unteroffizier Willi Maximowitz accounted for his with cannon fire, but Unteroffizier Hermann Wahlfeld’s chosen victim seemed impervious to shell or shot.

Unteroffizier Hermann Wahlfeld proved his commitment to the Sturmflieger’s creed by ramming a B-24 on 30 January 1944. He succeeded in baling out of his shattered Fw 190 without so much as a scratch

With the range diminishing rapidly, Wahlfeld remained true to the Sturm code and rammed the heavy bomber now filling his sights. His escape unscathed by parachute and subsequent return to Dortmund was a greater morale booster for the Staffel than any amount of armour plating. The two B-24s were firsts for both NCO pilots, and tally neatly with the two losses admitted by the Eighth Air Force – both the 93rd and 445th Bomb Groups each lost a Liberator on this raid.

Gefreiter Rudolf Pancherz joined Sturmstaffel 1 soon after the unit was formed, but was subsequently transferred to 3./JG 11 in late January 1944. Having claimed one victory with the latter unit, he was killed in a mid-air collision with another pilot from his Staffel on 3 March 1944

It was during this same mission that Major Bacsila was curiously credited with the Staffel’s first ‘official’ aerial victory. But the identification of Bacsila’s victim as a ‘Fortress II’ would seem to suggest that he had stuck closer to the Fw 190s of I./JG 1, who had engaged the much larger formation of B-17s targeting Brunswick.

30 January also saw Sturmstaffel 1’s first losses when Fähnrich Derp and Unteroffizier Heinz von Neuenstein (an ex-flying instructor) were both killed in action east of Hannover. Two other pilots were wounded and forced to take to their parachutes. In addition, four more machines are believed to have been completely written-off and a further six damaged. The three victories had been dearly bought.

These material losses had still not been made good by the time the Staffel next went up against the enemy. With little more than six Focke-Wulfs currently serviceable, there was no chance of Major von Kornatzki’s ‘decisive blow’ being delivered on 10 February when Sturmstaffel 1 again accompanied I./JG 1, first to Rheine, and then into action against another raid by the Eighth Air Force on Brunswick. In the event, just one victory was added to the Staffel’s’ scoreboard – a B-17 downed by Oberfähnrich Heinz Steffen not far from Rheine itself.

Ex-7./Jagdgruppe Ost instructor Unteroffizier Heinz von Neuenstein became one of Sturmstaffel 1’s first losses when he was killed in action east of Hannover on 30 January 1944

A frontline fighter pilot since 1940, Wolfgang Kosse had been demoted from hauptmann to flieger following an unauthorised flight that went wrong whilst serving with JG 5 in 1943. This photograph of Flieger Kosse was taken soon after he joined Sturmstaffel 1

Twenty-four hours later Steffen claimed his second Fortress when the Staffel was scrambled on its own for the first time. Another of the B-17 force sent to attack Frankfurt on 11 February was credited to Flieger Wolfgang Kosse.

Standing on the rain-soaked apron at Dortmund in early February 1944, the pilots of Sturmstaffel 1 prepare for an inspection. Indentifiable in this line-up are, from left to right, Oberleutnant Ottmar Zehart, Leutnant Hans-Georg Elser, Lt Friedrich Dammann, unknown, Feldwebel Gerhard Marburg, Unteroffizier Kurt Röhrich, Unteroffizier Werner Peinemann and Gefreiter Gerhard Vivroux

Flieger was the lowest rank in the Luftwaffe, the equivalent of AC2 or Private Second Class, and very few flieger were fighter pilots – unless, that is, they had been demoted from a higher rank, which is exactly what had happened to Wolfgang Kosse.

Kosse had claimed his first four kills while flying as a leutnant with JG 26 during the invasion of France and the Low Countries in May-June 1940. He added a brace of Hurricanes during the Battle of Britain as Staffelkapitän of 5./JG 26, and was credited with five further RAF victims during the cross-Channel skirmishing of 1941-42. After attending a gunnery course, the now Oberleutnant Kosse was transferred to JG 5 in Norway. Here, he captained 1. Staffel, apparently went on to claim a further six kills, and was promoted to hauptmann. Then something happened.

A post-war account claims that he performed an unauthorised flight and damaged an aircraft, although this incident was recorded in the unit history simply as an ‘abuse of powers of authority’. On 30 November 1943 Kosse was immediately demoted to flieger and sentenced to nine months imprisonment, the latter then commuted to probationary frontline service. Kosse presumably regarded volunteering for the Sturmstaffel as a means of rehabilitating himself, and his 18th kill – the B-17 of 11 February – was the first step on the long road back.

Ten days were to pass before the Staffel next engaged the US ‘heavies’. On 21 February, 24 hours into the Eighth’s ‘Big Week’ offensive, some 800 bombers, escorted by nearly 700 fighters, struck at Luftwaffe airfields and other targets in northwest Germany.

The Staffel’s activities were already beginning to attract attention. This still from a newsreel shot at Salzwedel in March 1944 shows Feldwebel Gerhard Marburg (left) and Unteroffizier Kurt Röhrich deep in conversation with one of the groundcrew

Again operating independently, Sturmstaffel 1 claimed two B-17s – one each for Feldwebel Gerhard Marburg and Unteroffizier Kurt Röhrich. The former was also credited with a Herausschuss. This term literally meant ‘shooting out’, whereby a heavy bomber had been damaged to such an extent that it was forced to abandon the safety of its combat box and become a lone straggler – easy pickings for any roving Luftwaffe fighter.

But these successes had cost the Staffel two more fatalities. Unteroffizier Erich Lambertus (who had transferred in from JG 26 only the previous month) and Unteroffizier Walter Köst were both shot down near Lübeck, on the Baltic coast, in two of the Staffel’s new Fw 190A-7s.

One of Sturmstaffel 1’s earliest volunteers, Unteroffizier Erich Lambertus had joined the unit from 2./JG 26 on 19 January 1944. He was killed in action flying Fw 190A-7 ‘White 3’ over Lübeck on 21 February

Unteroffizier Walter Köst was also killed in action on 21 February 1944, being hit over Sundern by defensive fire from one of the B-17s he had attempted to shoot down

The Fw 190A-7 boasted a number of technical and mechanical improvements over the A-6, as well as four wing-mounted 20 mm cannon augmented by a pair of fuselage-mounted MG 131 13 mm machine guns

This latest variant from the Focke-Wulf stable differed from the previous A-6 model primarily by having its two 7.9 mm MG 17 fuselage machine guns replaced by heavier 13 mm MG 131s. But this upgrading was fairly academic as far as the Sturmstaffel was concerned, as the fuselage armament was usually removed anyway.

On 22 February the Eighth Air Force turned its attention from airfields to aircraft factories, but severe weather conditions over northwest Europe resulted in the majority of the bombers either aborting or being recalled. Some 38 B-17s were lost in action nonetheless, one going down to the guns of the Staffelführer Leutnant Werner Gerth.

Sturmstaffel 1 shared Salzwedel with IV./JG 3, one of whose Bf 109Gs may just be made out in the background at far left

Four days later Sturmstaffel 1 ended its brief association with I./JG 1 when its ten serviceable machines were ordered to transfer to Salzwedel – an airfield approximately midway between Hamburg and Berlin. The Bf 109G-6s of IV./JG 3 ‘Udet’ had also transferred in to Salzwedel (from Venlo, in Holland) on this same 26 February. Commanded as from this date by Major Friedrich-Karl Müller, IV./JG 3 had only recently been assigned to Defence of the Reich duties after service in Sicily and Italy during the latter half of 1943. The new base was to bring a change of fortunes for both IV./JG 3 and Sturmstaffel 1.

Major Friedrich-Karl Müller, Gruppenkommandeur of IV./JG 3, is seen here wearing the Oak Leaves that he was awarded for claiming 100 victories while serving as Staffelkapitän of I./JG 53 on the Russian front

After an unsuccessful first attempt to attack Berlin on 3 March 1944 (which was thwarted by bad weather), the Eighth Air Force had marginally better luck under similar conditions the following day when a single combat wing of 30 B-17s managed to get through to the German capital. Five of this small attacking force – the first US aircraft to bomb Berlin – were lost. One was claimed by a pilot of IV./JG 3 and two were credited to the Sturmstaffel.

Having scrambled from Salzwedel at about 1230 hrs, and spent the next hour searching, the Staffel finally located the bomber formation over Neuruppin, some 37 miles (60 km) to the northwest of the capital. A stern attack to within a few feet of the rearmost machines sent two of the B-17s down within seconds of each other. One was a first for Unteroffizier Gerhard Vivroux, while the other was victory number two for Feldwebel Hermann Wahlfeld who, on this occasion, did not have to resort to ramming! The Staffel’s sole casualty was Feldwebel Werner Peinemann, shot down wounded between Neuruppin and Salzwedel.

Sturmstaffel 1’s Unteroffizier Gerhard Vivroux, Unteroffizier Hermann Wahlfeld, Major Erwin Bacsila (wearing in a highly prized USAAF flying jacket) and Feldwebel Werner Peinemann pose for a photo just prior to the 4 March mission in defence of Berlin. Vivroux downed a B-17 during this mission and Wahlfeld got two, but Peinemann was shot down and wounded

Forty-eight hours later a third attempt at ‘Big B’, as Berlin had promptly been christened by the US bomber crews, was an altogether different story. The Eighth Air Force’s Mission No 250 of 6 March 1944 comprised 730 B-17s and B-24s, accompanied by 800 escort fighters. This time not even the heavy cloud cover was going to be able to protect the capital of Hitler’s Reich. But the Luftwaffe, alerted by the earlier aborted raids, had been given plenty of time to gather its defences. A total of 18 Jagdgruppen, three Zerstörergruppen, four Nachtjagdgruppen and sundry lesser units awaited the approaching Americans.

Into this aerial arena, crowded with some 2,000 combat aircraft, friend an foe alike, Sturmstaffel 1 was able to despatch just seven Fw 190s. Their contribution might seem miniscule, but between them the seven Sturmjäger would be credited with seven B-17s destroyed – their greatest success to date, and a figure which alone represented ten per cent of Mission No 250’s total heavy bomber losses!

It had been approximately 1130 hrs when the seven Focke-Wulfs were scrambled from Salzwedel in the company of IV./JG 3’s Bf 109s. Climbing steadily, they set course south-eastwards for the Magdeburg area, 62 miles (100 km) distant, where they were to rendezvous with other fighter units at an altitude of 26,000 ft (7,900 m). All went to plan, and soon the van of the huge US bomber stream was sighted approaching from the direction of Brunswick.

Some 15 Fw 190s (most of them A-7s) of Sturmstaffel 1 sit on the ramp outside the hangar at Salzwedel in early March 1944. Most are carrying drop tanks, and they all seem to feature the black-whiteblack fuselage identification bands of the Sturmstaffel

In the face of such overwhelming enemy strength it was obviously impossible to use Sturmstaffel 1’s seven Fw 190s in the role originally envisaged for them by von Kornatzki – ‘to make the initial pass, smash a breach in the enemy’s defences and cause disruption among his ranks’. Instead, the twin-engined Messerschmitts went in first with heavy cannons and rockets, followed by the single-seat fighters. Then it was the Sturmjägers’ turn.

Three B-17s fell to their first onslaught, all logged as going down at 1235 hrs – one apiece for Leutnant Gerhard Dost and Unteroffizier Kurt Röhrich, and an Herausschuss for Unteroffizier Willi Maximowitz. Two more Fortresses were then claimed by Oberleutnant Ottmar Zehart and Unteroffizier Hermann Wahlfeld, and a final brace were credited to Leutnant Werner Gerth, the last shot down at 1408 hrs.

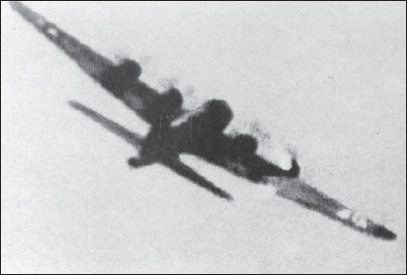

A classic Herausschuss as a 1st Bomb Division B-17 drops away with its starboard outer engine on fire

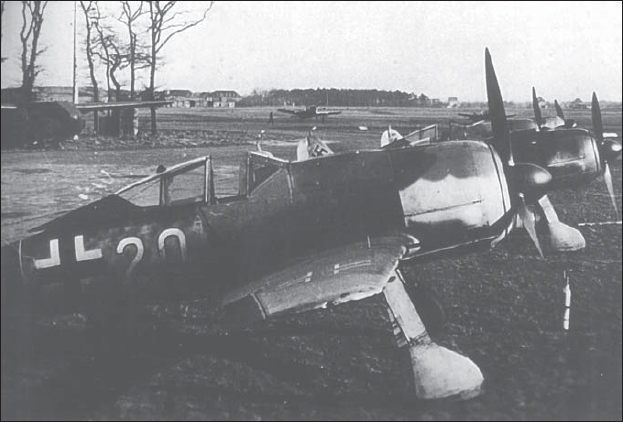

The Staffel’s sole casualty was Gerhard Dost who, after claiming his first victory in the initial pass, was last seen on the tail of a straggling B-17. Intent on adding a second kill to his scoreboard, he did not spot the pair of P-51s diving to the bomber’s aid until it was too late. He turned into his attackers, but the heavy Sturmjäger (which only now jettisoned its drop tank) was no match for the two Mustangs. The American fighters circled Dost’s machine, forcing it to lose altitude in a tight spiral. At 5000 ft (1500 m) it stalled out while trying to turn inside the P-51s and crashed into the ground not far from Salzwedel. Neither American pilot had been able to get in a single shot at Dost’s ‘White 20’ during the steep, wildly gyrating 400 mph (645 km/h) chase.

The survivor from a 91st BG Fortress brought down north of Magdeburg during this action has described being attacked from astern by a trio of Fw 190s, one of which lost height a little, before climbing ‘relentlessly’ straight towards the B-17 and knocking its starboard tailplane off in the resulting collision. There is no mention of a deliberate ramming attack in the Luftwaffe’s list of kills, but it seems almost certain that this incident involved an aircraft of Sturmstaffel 1. The only clue to the pilot’s identity is afforded by the time of the bomber’s loss – given as ‘approximately 1250 hrs’ – which would best tie in with Ottmar Zehart’s claim of 1255 hrs.

6 March 1944 was also the most successful day to date for the pilots of IV./JG 3, who claimed 13 enemy aircraft without loss to themselves. Forty-eight hours later, when the Eighth Air Force again struck at Berlin, the unit was credited with another dozen victories, although this time one pilot was killed and two wounded. The Sturmstaffel’s sole success on 8 March was a single B-17 downed by Leutnant Richard Franz (to add to his one B-17 claimed during his earlier service with JG 77 in Italy).

Leutnant Gerhard Dost scored his first victory over a B-17 on 6 March, but he was in turn set upon by escorting P-51Bs and killed when his heavy Sturmjäger stalled and crashed after Dost had tried to turn inside his attackers

‘White 1’ and ‘2’ sit out on a rather damp apron in front of their Salzwedel hangar as they are readied for another mission. Although the former was the Kapitän’s assigned machine . . .

. . . Major von Kornatzki normally flew ‘White 20’, seen here basking in the early spring sunshine. Note what appears to be a Gotha Go 242 transport glider in the background left

Severe weather largely protected Berlin from another raid on 9 March, but it also kept the Staffel anchored firmly to the ground at Salzwedel. The bad weather would continue for another fortnight, and it was not until 23 March that the Sturmjäger next saw action. Although conditions were still far from good, Sturmstaffel 1, again in the company of IV./JG 3, was scrambled against US ‘heavies’ raiding targets in northwest Germany. After an hour’s searching, they found a formation of bombers north of the Ruhr and brought down six of their number (three of them Herausschüsse) in the space of ten minutes.

Reflecting on a close encounter with a P-51B, Unteroffizier Hermann Wahlfeld sits in the cockpit of his Fw 190, its starboard ‘blinker’ panel shattered by a 0.50-in machine gun round. Although Wahlfeld’s luck held out on this occasion, it deserted him on 23 March 1944 when he was shot down and killed near Lippstadt. His tally stood at three victories at the time of his death

Four of the victors – Kasse, Maximowitz, Röhrich and Vivroux – already had Sturm kills under their belts, but two of the Herausschüsse were firsts, one going to Friedrich Dammann and the other to Major Hans-Günter Kornatzki (who was making one of his rare operational flights on this date), which took his tally of wartime victories to five.

Unteroffizier Willi Maximowitz (left) and Gefreiter Gerhard Vivroux pose with Fw 190A-6 ‘White 2’ at Dortmund in early 1944. Note the Sturmstaffel 1 emblem adorning the fighter’s nose and the ‘blinkers’ fitted to its canopy

The Staffel did not escape without loss, however. Unteroffizier Hermann Wahlfeld, who had carried out the first recorded ramming attack, was shot down and killed near Lippstadt. Feldwebel Otto Weissenberger suffered a similar fate west of Bocholt. The latter, an early volunteer, had not scored while with the Staffel, although he had previously served with JG 5 in the far north alongside his elder brother, Theodor, who was by this time an Oak Leaves-wearing Experte with 148 victories to his name. The third casualty was Unteroffizier Willi Maximowitz, forced to bale out wounded over Wuppertal.

Further proof that the Panzerglas ‘blinkers’ did indeed work in combat. Unteroffizier Willi Maximowitz’s ‘White 10’ has been struck in the fuselage and cockpit by at least two machine gun rounds

The Staffel’s first fighter kill was a P-47D Thunderbolt downed on 11 April 1944. The Ninth Air Force’s 362nd FG, to which the machine shown here belonged, was up that day, and lost one of the seven P-47s reported missing

Once again the weather clamped down, resulting in another long period of inactivity until the Staffel’s next engagement on 8 April. The Eighth Air Force was still targeting Luftwaffe airfields and installations in northwest Germany, and Sturmstaffel 1 (together with IV./JG 3) was part of the force sent up against the bombers. Making contact with a formation of B-24s west of Brunswick, four of the more experienced pilots were able to add to their growing list of victories, claiming a trio of Liberators and an errant Fortress. But three others were not so fortunate. Unteroffiziere Karl Rohde and Walter Kukuk, neither of whom had yet scored, and Leutnant Friedrich Dammann, who had been credited with a B-17 Herausschuss 16 days earlier, all went down north of Brunswick.

The following day’s single success was a B-24, which Flieger Wolfgang Kosse was able to add to the two B-17s he had already claimed as an ongoing part of his rehabilitation process. Then, on 11 April, it was back to multiple kills – nine in all, including the Staffel’s first US fighter.

Austrian Unteroffizier Kurt Röhrich was the first pilot to claim a fighter destroyed for Sturmstaffel 1 when he downed a P-47D on 11 April. He had been credited with 12 victories by the time of his death on 19 July

Once again, the Eighth Air Force’s targets were Germany’s airfields and aircraft factories. Having scrambled from Salzwedel shortly after 1000 hrs (together with IV./JG 3 as usual), Sturmstaffel 1 was vectored towards a formation of some 50 B-24s in the Hildesheim area. Five Liberators went down in the first attack timed at 1115 hrs – one each for Metz, Müller, Röhrich (Herausschuss), Marburg and Gerth. The latter pair claimed another B-24 apiece in a second pass only minutes later. It was Unteroffizier Kurt Röhrich who also got a P-47 Thunderbolt, which was the first enemy fighter to fall to the Staffel.

Ex-JG 5 pilot Leutnant Rudolf Metz was amongst the ranks of Sturmstaffel 1’s victorious pilots on 11 April, when the unit claimed five B-24s (one Herausschuss) over Hildesheim in just 60 seconds. Serving with 11./JG 3 between 9 May and 30 June, Metz was then posted to II.(Sturm)/JG 4. Having increased his tally to ten victories, he was killed in action while serving with 6.(Sturm)/JG 4 on 6 October 1944

After refuelling and re-arming back at Salzwedel, another mission was flown early in the afternoon which resulted in a B-17 for Unteroffizier Gerhard Vivroux. Nine victories for no casualties was by far Sturmstaffel 1’s best performance to date. The same applied to IV./JG 3, which was credited with no fewer than 25 enemy aircraft (two-dozen B-17s and a single P-38) for one pilot killed and one wounded in combat.

After the success of 11 April, the claim for just five B-17s without loss two days later might appear almost anti-climactic. But the clinical way in which this quintet had been scythed from a formation of some 150 Fortresses west of Schweinfurt, all within the space of a minute, was a telling demonstration of Sturm tactics. Three of the bombers fell to old hands, being the fourth, fifth and sixth victories for Gerhard Vivroux, Siegfried Müller and Werner Gerth, respectively. The remaining two, both Herausschüsse, were firsts for Unteroffiziere Karl-Heinz Schmidt and Heinrich Fink.

Twenty-four hours later the unfortunate Unteroffizier Fink was to become the Staffel’s eleventh, and final, combat fatality when shot down in unknown circumstances in the Stuttgart area.

Armourers hastily attend to the reloading of one of the wing-mounted 20 mm MG 151/20 cannon fitted to a Sturmstaffel 1 Fw 190A-7 at Salzwedel in early April 1944. The fighter’s spinner and cowling are streaked with engine fluid and gun muzzle deposits

Sturmstaffel 1 was now rapidly approaching the end of its six-month trial period. The unit’s performance, especially of late, had obviously impressed the upper hierarchy, for on 15 April General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland visited Salzwedel not only to congratulate von Kornatzki and his pilots, but also – and perhaps more importantly – to announce that IV./JG 3 had been selected to become the Luftwaffe’s first official Sturmgruppe!

The General’s plans called for IV./JG 3 to convert from its Bf 109G-6s to Fw 190A Sturmjäger – remaining operational throughout – and to incorporate Sturmstaffel 1 into its ranks as a new 11.(Sturm)/JG 3. But for the next fortnight, while orders were being cut and details finalised, Sturmstaffel 1 would continue to operate under its original designation.

On 18 April the Eighth Air Force returned to aviation industry targets in the Greater Berlin area. This time the bad weather, which seemed an almost permanent feature of Berlin ops during this period, worked against the defenders. Although IV./JG 3 and the Sturmstaffel scrambled from Salzwedel safely enough, they were unable to rendezvous with other units as planned. Sturmstaffel 1 was the first to find and engage a formation of B-17s, escorted by fighters, some 37 miles (60 km) to the west of the capital. Kurt Röhrich and Wolfgang Kosse – the latter now elevated to the rank of gefreiter (AC1 or PFC) – were credited with a Fortress each, while Oberfeldwebel Gerhard Marburg was able to bring down a P-51 in a separate action 20 minutes later.

On 24 April Sturmstaffel 1 claimed no fewer than seven B-17 Herausschüsse in the Munich area. Could the 384th BG’s BOOBY TRAP, seen here on her belly in the shadow of the Alps, perhaps have been one of them?

But it was the Staffel’s swansong, on 29 April, which proved to be its finest hour. Once again the Eighth Air Force (over 600 bombers escorted by more than 800 fighters) had its sights on Berlin.

For the last time, IV./JG 3 and Sturmstaffel 1 lifted off from Salzwedel – in company, but as separate entities. At the rendezvous point the Bf 109s joined up with other Jagdgruppen before setting off for the Magdeburg area, where strong enemy forces had been reported. These were engaged by IV./JG 3 using their customary frontal attack tactics. The Gruppe claimed nine B-17s and five B-24s (four of the Fortresses and all five Liberators being Herausschüsse).

Meanwhile, the Sturmstaffel had found a formation of B-17s to the northeast of Brunswick. Relying on their usual stern approach, the heavily armoured Sturmjäger bored in. The next five or six minutes were both the culmination of Sturmstaffel 1’s short-lived history and the most convincing demonstration to date of Major von Kornatzki’s original close-quarter concept.

Thirteen Fortresses were hacked down. As was to be expected, it was again the more experienced pilots – by now the ‘Alten Hase’ (Old Hares) of Sturm tactics – who gained the lion’s share of the successes. Both Werner Gerth and Kurt Röhrich took their Sturm scores to eight, the former with a double victory. Wolfgang Kosse also claimed a brace (both of them Herausschüsse) in this action, but two of the three remaining Herausschüsse were firsts for Unteroffiziere Helmut Keune and Oskar Bösch.

Unteroffizier Oskar Bösch’s first victory was a B-17 Herausschuss northeast of Brunswick on 29 April 1944 . . .

Throughout its six-month operational career, the Staffel had welcomed a small but steady stream of new volunteers to its ranks. Oskar Bösch had been one of the last to reach the unit, as he explained to the Author;

‘Although my travel orders directed me to report to JG 3, I volunteered instead for Sturmstaffel 1. A few days later I arrived at Salzwedel. As I had never flown an Fw 190 before, I was first given a short introduction and then allowed to practise four take-offs and do a few circuits.

. . . and here the victor poses (right) with his mechanic on the wing of his Fw 190A-7. Note that although the fuselage-mounted MG 131 machine guns have been removed, the barrel troughs (on top of the cowling) have not been faired over

‘The next day, 29 April 1944, I took off on my first operational mission. We did not open fire until we had approached to within a few metres of the bombers. During this mission our unit shot down 22 (sic) Viermotorige, one of which was credited to me. As my fuel was running low I had to land at Bernburg, where my Fw 190A-7 somersaulted and I was slightly injured.’

When Oskar Bösch returned to ops nine days later, he would find himself a member of JG 3 after all, for a top secret communication from OKL (Luftwaffe High Command) HQ, dated 29 April 1944 and headed ‘Activation of a Sturmgruppe’, began with the words;

‘1. With immediate effect

(a) IV./JG 3 is to be redesignated and converted into IV./(Sturm)/JG 3

(b) and Sturmstaffel 1 is to be disbanded.’

The document then went into administrative detail, specifying, among other points, that personnel from the disbanded Sturmstaffel were to be integrated into the newly created Sturmgruppe (the majority would, in fact, be used to establish the new 11. Staffel), and that IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was to be re-equipped with Fw 190 Sturm aircraft, its Bf 109Gs being passed mainly to the other Gruppen of JG 3 to help make good any current shortfalls.

The pioneering, almost buccaneering, days of the all-volunteer Sturmstaffel were over. Major von Kornatzki’s theories had been proven and accepted by those in authority. The strength of the Sturm force had been trebled, and it was now to form part of the regular Luftwaffe establishment. Not all welcomed the change.

The 15 pilots of Sturmstaffel 1 link arms for a commemorative snapshot at Salzwedel on 29 April 1944. The full line-up, from left to right is, Oberleutnant Zehart, Leutnant Elser, Leutnant Müller, Leutnant Metz, Major von Kornatzki, Leutnant Gerth, Feldwebel Röhrich, Leutnant Franz, Feldwebel Kosse, Oberfeldwebel Marburg, Feldwebel Peinemann, Unteroffizier Maximowitz, Feldwebel Groten, Unteroffizier Bösch and Unteroffizier Keune. Only three of these pilots would survive the war