Even before the main ground party reached Eisenstadt, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s Focke-Wulfs were on the move again. This time their destination was Ansbach, some 25 miles (40 km) southwest of Nuremberg. Arriving here on 21 June, and joined by 2./JG 51 – the latter now fully reconverted back on to Focke-Wulfs – the Gruppe resumed the training that had been interrupted by the foray into France.

This now consisted primarily of the three Staffeln perfecting their broad arrowhead approach flight formation, with 2./JG 51 flying cover in a similar, smaller arrowhead to the rear of, and slightly above, the main group. During this approach phase, the formation would follow the instructions of a ground-controller whose job it was to vector the Gruppe towards the enemy bomber stream. Once visual contact had been made, however, the leader in the air – usually Hauptmann Moritz – would order the arrowhead to split into its individual Staffeln (or even smaller units, such as Schwärmen, depending upon the size and composition of the enemy force to be attacked). Each one would then be assigned a specific box, or flight, of bombers as its target. If the Focke-Wulfs of 2./JG 51 were still in attendance and had not been drawn off into combat with enemy fighters, they too would be allocated a section of bombers to attack.

To achieve the maximum destructive effect, the order to fire would also be given by the unit leader. Officially, the Sturm pilots were supposed to be within 100 metres (110 yards) of the bombers before opening fire, but in practice the order to open up with the 20 mm cannon was usually given at a range of 400 metres, with the 30 mm outer wing MK 108s adding their extra punch at 200 metres. The latter weapons’ ammunition magazines contained only 55 rounds per gun, which gave the pilot a fraction over five seconds of fire. It should be borne in mind, however, that just three rounds – literally a split-second burst – were usually enough to bring down a heavy bomber!

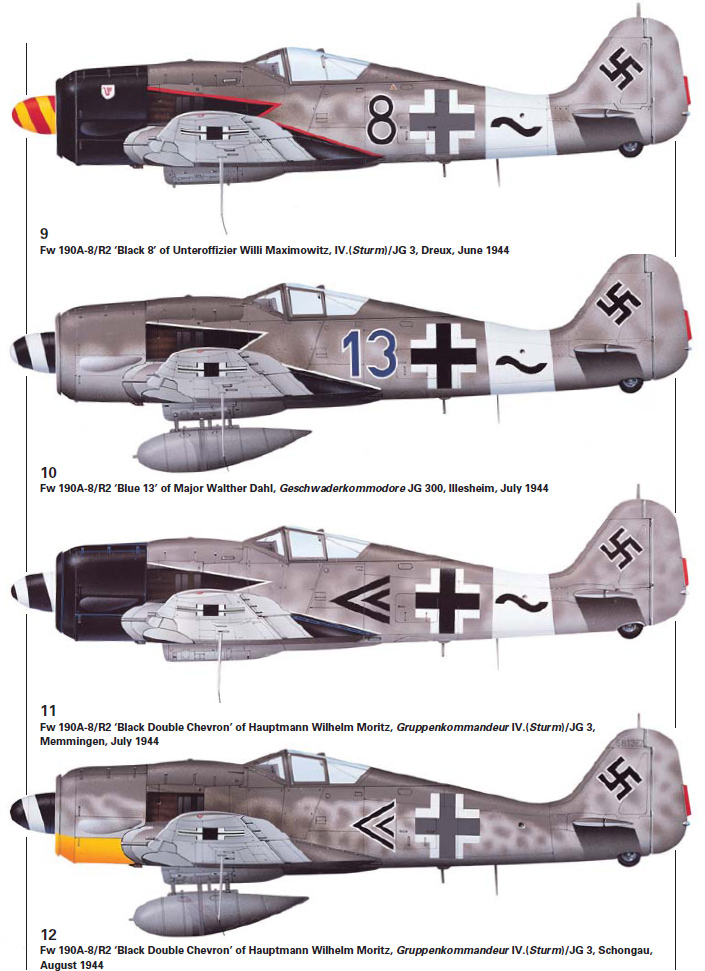

Upon moving to Ansbach, in southern Germany IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 had come under the control of 7. Jagddivision, headquartered in Munich. For operational purposes, the Gruppe was attached to Major Walther Dahl’s JG 300.

This Geschwader had its origins in an experimental unit set up in June 1943 by ex-bomber pilot Major Hajo Herrmann, who contended that single-engined fighters could operate just as effectively by night as by day. Employed in the immediate vicinity of those areas under attack by RAF Bomber Command, where the night sky would be artificially illuminated by searchlights and flares, as well as by fires from the ground target below, the Luftwaffe’s single-seaters (which were not equipped with radar) would be able to hunt the enemy bombers by purely visual means alone. This simple form of nightfighting, which was code-named ‘Wilde Sau’ (‘Wild Boar’), achieved some significant early successes. But it proved costly too, and gradually the unit’s role changed, firstly from night to all-weather fighters and then, after some six months, to fully blown daylight defence fighters.

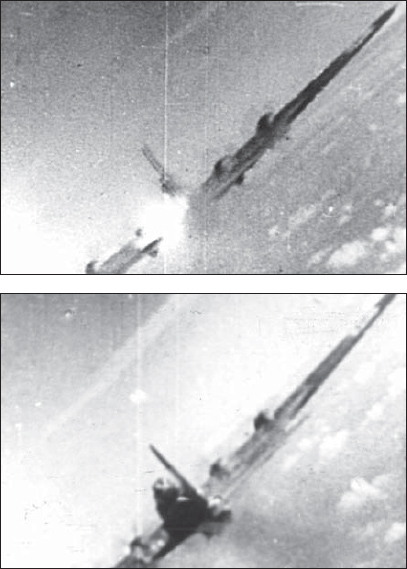

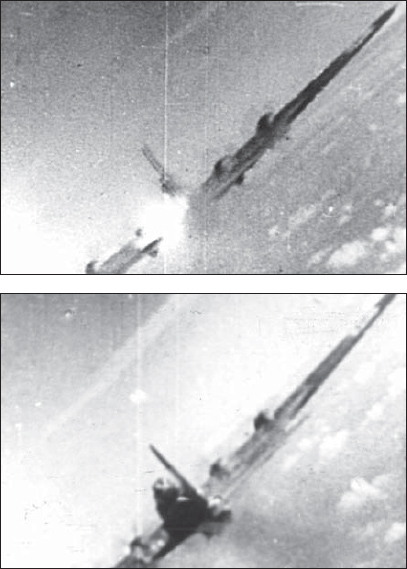

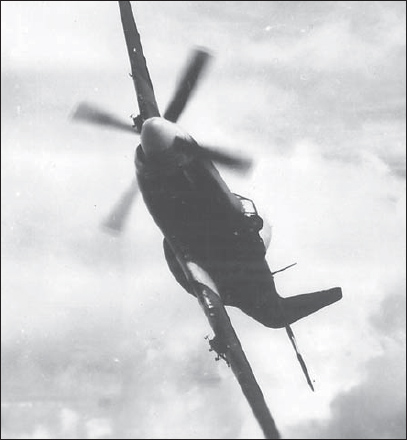

Putting Normandy behind him, Feldwebel Maximowitz next demonstrates a classic Sturm attack with these three gun-camera stills recording the demise of a Fortress . . .

By the early summer of 1944, JG 300’s three Gruppen – two of Bf 109s and one of Fw 190s – formed a cornerstone in the Defence of the Reich’s order of battle. Indeed, it was the one complete Jagdgeschwader to be retained in Germany when all the others were despatched to the Normandy front. Major Dahl, the Geschwader’s third Kommodore, had only just taken office. Prior to that he had spent two years as a member of JG 3, the last ten months of them as Kommandeur of III. Gruppe.

On 6 July 1944 Hauptmann Moritz and his men were ordered to move for the third time in as many weeks. A short hop north-westwards took them from Ansbach to Illesheim. Here they would also stay for just seven days, but they would be days long remembered.

. . . note the range from which the last frame was shot – just 90 metres, or 295 ft!

The Eighth Air Force’s Mission No 458 of 7 July was a major effort by all three bomb divisions, which despatched over 1100 B-17s and B-24s in total against strategic oil, ball-bearing and aviation industry targets throughout Germany.

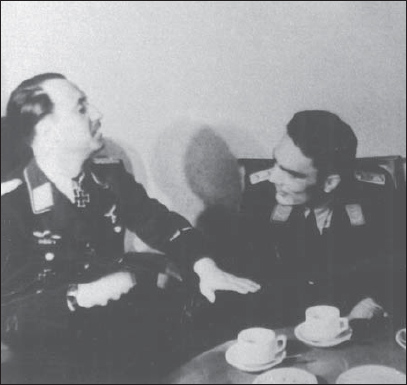

The much-decorated Major Walther Dahl, Kommodore of JG 300 – the Geschwader to which IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was attached upon its return from Normandy

At 0820 hrs on their first morning at Illesheim, 44 Fw 190s of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 were scrambled to meet the attackers. At the same time Major Dahl and his three Gruppen of JG 300 lifted off from other nearby fields to the west of Nuremberg. Although the Moritz and Dahl formations were both ordered to fly northwards, they were on parallel but slightly divergent courses, and they never actually made contact with each other in the air.

Walther Dahl’s mixed force of Bf 109s and Fw 190s was vectored towards several groups of ‘heavies’ in the Halberstadt-Quedlinburg area. In a sprawling series of engagements they claimed 29 bombers (27 B-24s and two B-17s) and six of their escorting fighters (four P-51s and two P-38s) between them.

Meanwhile, at least 20 miles (32 km) away to the north-northwest over the town of Oschersleben, Hauptmann Moritz’s Focke-Wulfs had had the good fortune to encounter part of another bomber stream – a box of B-24s which, at that moment, was apparently devoid of all fighter cover. For the first time, and under near ideal conditions, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s pilots were thus able to mount a concerted stern attack of the kind they had so assiduously practised over the past weeks.

A B-24 Liberator under attack from astern takes hits on the tail and port inner engine

The effects of near simultaneous salvoes from more than eighty 30 mm cannon were devastating. As they barrelled through a sky of exploding, wildly spinning Liberators, the Fw 190 pilots were convinced that they had destroyed the entire box. With ammunition to spare, many of them went after a second formation of B-24s visible ahead of the first. In less than ten minutes the Gruppe had claimed a staggering 34 B-24s downed!

Among the victors, Hauptmann Moritz’s single Herausschuss had boosted his total to 40. Werner Gerth of the original Sturmstaffel added two confirmed to his tally. The eastern front Experten of the attached 2./JG 51 contributed no fewer than 11 victories in this, their first Defence of the Reich action. A pair for Staffelkapitän Oberleutnant Horst Haase raised his overall score to 48, and a singleton for the Staffel’s most successful pilot, Leutnant Oskar Romm, took his tally to 77.

Even 12./JG 3, incredibly still toting their under-fuselage rocket launchers, were credited with eight of the Liberators. Having been part of the massed attack from astern, 12. Staffel’s pilots had had no opportunity to fire their rockets. The added weight of these missiles, whose very presence precluded the use of belly tanks, meant that 12./JG 3’s fighters were much ‘shorter legged’ than those of the other Staffeln and, consequently, they had to look for suitable fields in the area where they could land and refuel, before returning to Illesheim.

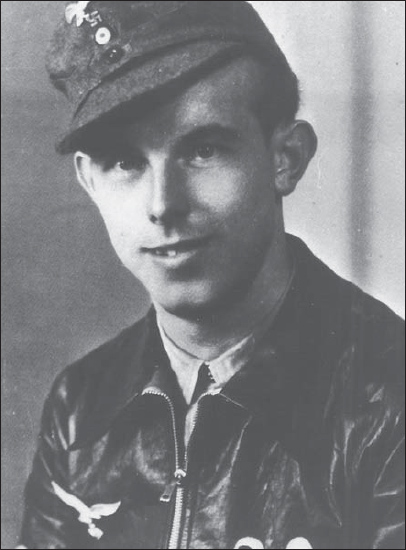

Leutnant Oskar Romm, wearing the Knight’s Cross awarded on 29 February 1944 for his 76 eastern front victories

Several opted for Bernburg, about 27 miles (44 km) to the southwest of the scene of the recent action. It was a fateful decision for Staffelkapitän Oberleutnant Hans Rachner, who was caught and shot down by P-51s just nine miles (14 km) short of his goal. The Mustangs also accounted for his wingman, Oberfähnrich Hans-Joachim Voss. Not that Bernburg provided much of a haven. The field had been one of the Eighth Air Force’s objectives of the day, and 10. Staffel’s Leutnant Alois Maier lost his life while attempting to belly-land his damaged Fw 190 on its freshly cratered runway.

These were three of the day’s five fatalities. The others were both members of 2./JG 51. Leutnant Werner Koch fell victim to return fire from the B-24s, while Unteroffizier Erich Nissler, who had put down briefly at Halberstadt en route back to Illesheim, was killed when his Fw 190 swung as he took off again. The only other casualty was Leutnant Hans Iffland of Hauptmann Moritz’s Gruppenstab. Also hit by fire from the Liberators’ gunners, the wounded Iffland baled out near Halberstadt.

As the after-action reports began to come in to 7. Jagddivision HQ, it quickly became apparent that the defending fighters had scored a signal victory. Over 80 claims had been made in all, but it was the Sturmgruppe’s conviction that they had blown an entire enemy bomber formation out of the sky that grabbed the attention of the Luftwaffe brass and the imagination of the Reich’s propaganda minister, Dr Josef Goebbels.

In the event, US sources would show that the 492nd BG – the unit first attacked by IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 – had lost 12 of its Liberators.

That same afternoon, even before Hauptmann Moritz had himself returned to base (he had landed at an airfield near Magdeburg as a precautionary measure to have makeshift repairs carried out on his damaged Focke-Wulf), both the divisional commander, Generalmajor Huth, and General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland had flown in to Illesheim to get a first-hand account of the Gruppe’s achievement.

To Galland’s mind this was exactly the outcome predicted by Major von Kornatzki when he had first proposed the Sturm idea nine months earlier. However, the General did not lose sight of the fact that this one Gruppe’s success, spectacular as it may have been, had not prevented the rest of the enemy bombers from getting through to their targets. To stop the Eighth Air Force in its tracks an even heavier blow was needed, and so, just as Sturmstaffel 1’s initial successes had led to the creation of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3, the latter’s present accomplishments were to be the trigger for the activation of further Sturmgruppen.

But time and the worsening war situation were not on the Luftwaffe’s side. Just two further Jagdgruppen would see employment in the Sturm role. One, already flying Focke-Wulfs, would be converted and operational in five weeks, but the second, created from scratch, would not be combat ready until a month after that. In the meantime, with the Allies threatening to break out of their Normandy bridgehead and the Eighth Air Force preparing to resume its all-out daylight offensive against the Reich, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 would continue to soldier on alone.

The publicity engendered by the Gruppe’s success on 7 July would have even longer-lasting consequences – and of a very different kind. Eager for any item of genuinely good news by this stage of the war, the propaganda ministry in Berlin went into overdrive. Reports of the ‘Blitzluftschlacht (Lightning air battle) of Oschersleben’ appeared in newspapers and magazines throughout the land. Newsreel teams descended on Illesheim and footage of the Gruppe’s Focke-Wulfs restaging the action were shown in cinemas nationwide.

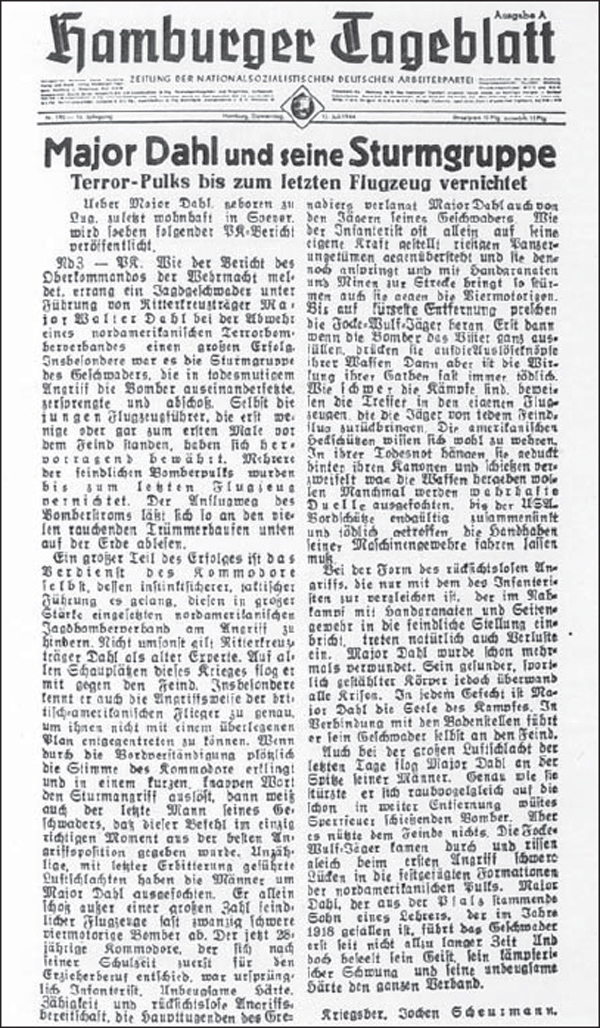

Whether by accident or design, great emphasis was being placed on the part played by Major Walther Dahl, the Geschwaderkommodore of JG 300. The impression was given that he, personally, had led the Sturmgruppe into the attack over Oschersleben. Below such headlines as ‘Major Dahl and his Sturmgruppe’ (admittedly, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was under attachment to his command at the time) there would follow accounts of the action written in the usual bombastic style of the day. A typical passage, for example, read;

‘It is thanks in no small measure to the instinctive, tactical leadership of the Kommodore that this strong formation of fighter-bombers (sic) could be brought under attack. When the voice of the Kommodore suddenly rang out over the R/T, giving in short, concise words the order to launch the Sturm assault, then every last pilot in the formation was certain in the knowledge that this order had been given at exactly the right moment, and when he was in precisely the right position, to commence the attack.’

The propaganda bandwagon starts rolling. This article on the front page of Thursday 13 July 1944’s Hamburger Tageblatt – Newspaper of the National-Socialist German Workers’ Party – is headed, ‘Major Dahl and his Sturmgruppe – Terror-formations destroyed to the last aircraft’

Another magazine – kept (and annotated) by a Sturm pilot for over 60 years – featured illustrations. Under the title ‘Stormers of the Air’, this photograph shows members of 10. Staffel who were credited with eight of the 34 Oschersleben victories . . .

Even though he was known to be some miles away with the Halberstadt-Quedlinburg force at the time (where, according to his own after-action report, he had spent ten minutes trying to unblock his jammed guns!), Major Dahl made little or no effort to set the record straight. To be fair, once the propaganda machine was in full cry, it is doubtful whether he could have done so, even had he wanted to. But when he subsequently attempted to have IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 redesignated and officially incorporated into JG 300, it reportedly led to a distinct cooling of relations between the Sturmgruppe and their temporary Geschwaderkommodore.

Nor did Dahl’s later book about those days in the Defence of the Reich help to clarify matters. Published in post-war Germany under the title Rammjäger (itself a misnomer), this patently self-serving work did not merely repeat the previous inaccuracies, it embroidered upon them. Now Dahl was portraying himself alongside Wilhelm Moritz leading the Oschersleben attack force;

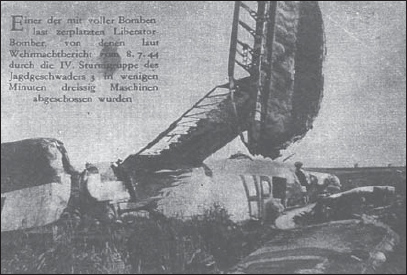

. . . and this is said to be one of the day’s victims. Close scrutiny of the original cutting reveals it to be Liberator HP-Z of the 389th BG’s 567th FS

‘“Negus 1 to Caesar 1”, I call to Hauptmann Moritz, “Do you see those two boxes in tight formation on the right flank? You take the left-hand one and I’ll take the right!” Wingtip to wingtip, tucked in closely, we begin the second attack – the actual Sturm attack – from a shallow angle of 20 degrees below. Only some 600 metres (655 yards) now separate us from the bombers.

‘The first stabs of fire erupt from the bombers’ machine gun turrets. Our angle of approach is good. It can only be a matter of seconds before all hell breaks loose again. I give the order, “To all little brothers – close up tighter still for the Sturm attack! If you can’t shoot one down, ram! Raaabaza-nella!!”’

This newsreel shot of a smiling Major Dahl (left) and Hauptmann Moritz appeared in newspapers and periodicals nationwide

This total fabrication of events, ending with Dahl’s own personal battle cry, together with the vastly inflated figures for enemy aircraft destroyed that are quoted in his book (greater even than the claims made at the time in the heat of battle), still rankled with some ex-members of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 more than 40 years later!

Behind the scenes, the expressions were a little more serious as Major Dahl makes a point to the assembled pilots of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3

Putting the apparent injustice of Oschersleben behind them, Hauptmann Moritz and his pilots transferred to Memmingen, some 62 miles (100 km) west-southwest of Munich, on 13 July. Here they were ideally placed to test their new-found muscle against the southern half of the USAAF’s combined strategic daylight bomber offensive against the Reich – the aircraft of the Fifteenth Air Force flying up across the Alps from their bases in Italy. Within five days they would get their chance, and claim the greatest success of their entire operational career.

In the left background of this frame – showing Dahl, Moritz and a group of officers including, second from left, 10. Staffel’s Oberleutant Ekkehard Tichy – is a Sturmbock clearly bearing the number ‘13’

This photograpjh of the same aircraft, with another doing a victory pass overhead, was published in the Luftwaffe’s own magazine Der Adler (The Eagle). Was Major Dahl photographed in the cockpit of this machine, as depicted by colour profile ten . . .

. . . or does this later shot of Major Dahl in another, ‘unblinkered’, aircraft show the real ‘Blue 13’?

On 18 July 1944 over 500 B-17s and B-24s of the Fifteenth Air Force, together with their escorting fighters, lifted of from their Italian airfields to strike at aviation targets in southern Germany. Luftwaffe radar operators in the south were no less efficient than their northern counterparts, and the early-warning organisation quickly picked up the enemy formations and began monitoring their approach. After 30 minutes at cockpit readiness, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was ordered to scramble from Memmingen shortly before 0930 hrs.

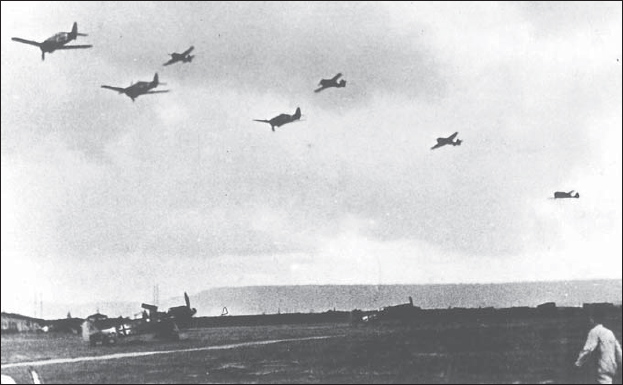

This still was taken from a propaganda company film shot on 15 July 1944 that purported to show IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 scrambling from Illesheim at the start of the Oschersleben mission. Close inspection of the machine on the ground (bottom left), with its breech cover hinged back, clearly reveals the absence of fuselage guns

For Hauptmann Moritz and his 40+ pilots, it was almost a rerun of the Oschersleben mission 11 days earlier. Vectored towards a strong force of B-17s coming in over Innsbruck, the Gruppe found itself on its own (Major Dahl’s three Gruppen, plus one from JG 27 based in Austria, had been directed against other parts of the bomber stream which was now splitting up to attack individual targets). Turning in behind a sizeable formation of B-17s heading resolutely northwards, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was forced to break off its first approach due to the presence of large numbers of enemy fighters.

Then the Gruppe sighted a box of bombers which had become separated from the main body. The oft-practised arrowhead formation had suffered somewhat in avoiding the first box, and consequently the attack on the second was a rather disjointed affair. Nevertheless, as the heavilyarmoured Sturmböcke knifed their way through, between and under the reeling Fortresses, it was clear that the Americans were being hit hard. Just how hard would become apparent when the post-action claims were assessed. In all, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 would be credited with a staggering 37 enemy bombers destroyed, plus a dozen Herausschüsse.

In contrast to missions flown by standard Jagdgruppen when, if contact was made with the enemy, the lion’s share of any resulting kills would usually go to a handful of the unit’s top-scoring Experten (and the crumbs to less experienced pilots), a Sturm attack – with everybody opening fire almost as one upon the given command, at close range and against a common, massed target – meant that victories were invariably spread evenly throughout the Gruppe.

When all the hubbub had died down, Major Dahl and Hauptmann Moritz found time to relax over a cup of coffee and discuss the mission

Of the estimated 42 pilots who participated in the initial attack on the unescorted box of B-17s and then went on to engage other Fortresses in the vicinity, no fewer than 37 were credited with at least one victory. Ten scored doubles. The most successful of all, and the only pilot to achieve a treble, was Leutnant Oskar Romm, who had been appointed Kapitän of 12. Staffel after the death of Hans Rachner. This brought ‘Ossi’ Romm’s overall score to 80. But the after-effects suffered by his having to bale out at high altitude meant that he would be off ops for the next two months.

Gruppenkommandeur Moritz’s single B-17 took his total to 41. And one apiece for two of his Staffelkapitäne, Oberleutnants Hans Weik of 10./JG 3 and Horst Haase of the attached 2./JG 51, raised their tallies to 36 and 49 respectively. Leutnant Werner Gerth was one of those credited with a double, and many other familiar names from the original Sturmstaffel 1 – among them Oskar Bösch and Willi Maximowitz – featured among the claimants.

Coming hard on the heels of Oschersleben, this even more successful action to the southwest of Munich on 18 July did not command quite as much media attention. But this time credit was given where credit was due. Lumping together the aircraft destroyed with those claimed as Herausschüsse, the following day’s High Command communiqué reported that;

‘The Fourth Gruppe of Jagdgeschwader 3, under the command of Hauptmann Moritz, alone brought down 49 four-engined bombers.’

This was somewhat different from the communiqué that had been issued 24 hours after Oschersleben, and which stated;

‘Fighting under the personal leadership of their Geschwaderkommodore Major Dahl, the IV. Sturmgruppe Jagdgeschwader 3, with their Kommandeur Hauptmann Moritz, particularly distinguished themselves by shooting down 30 four-engined bombers.’

A more tangible sign of recognition for Wilhelm Moritz’s handling and leadership of the Sturmgruppe came in the form of the immediate award of the Knight’s Cross, which was the first to be won by a serving Sturm pilot.

But 18 July had cost the Gruppe dear – six pilots killed in action, and a seventh so badly injured that he died the same day. Five of the fatalities had been tyros, shot down only minutes after claiming their first victories. Two had even been credited with doubles. Six other pilots had been wounded, including Hans Weik. Nor did the day’s losses end there.

Once again, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 had created undisputed havoc among a single bomber box. But, as at Oschersleben, the majority of the attacking force had got through to its assigned objectives. Unbeknown to Hauptmann Moritz and his pilots, their own base, Memmingen, had been this day’s primary target for almost half the bombers despatched by the Fifteenth Air Force. Some 200 Fortresses, in four separate waves, plastered the field, causing severe damage and heavy loss of life. Among the latter were 12 members of the Gruppe’s ground personnel. Of the nearly 60 aircraft destroyed or badly damaged on the ground (many of them twin-engined Zerstörer), eight of the unit’s Fw 190s were complete write-offs and a further 13 would require major repair.

After the euphoria of Oschersleben, reality soon set in again. And that reality came in the shapely form of the Mustang . . .

As a final postscript to this eventful day, it should be noted, perhaps, that the 483rd BG, which was the unescorted formation subjected to the Sturm attack, lost 14 of its Fortresses – a figure that was well under a third of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s total claims. But such was the ferocity of the Gruppe’s assault, and such the confusion reigning in that small patch of sky during those few indescribable minutes, that the bombers’ gunners later estimated that they had been under attack from 200 fighters, and had shot down 66 of them!

. . . which was beginning to take an ever-increasing toll of the Luftwaffe’s defending Fw 190s

In view of the devastation at Memmingen caused by the bombing raid, many of the Gruppe’s pilots opted to land first at Holzkirchen before returning to base later in the day. Two missions in the next 48 hours netted the depleted Gruppe five and eight B-17s respectively. But each cost IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 two pilots killed. The mission of 20 July, against a deep penetration raid by the Eighth Air Force, had taken the Gruppe well to the east of its usual stamping grounds. Having to land away from base to refuel, the Fw 190s did not begin arriving back at Memmingen for several hours.

In the interim, the field had been subjected to another attack by Fifteenth Air Force B-17s, which cost the lives of 15 more of the Gruppe’s ground staff. Hauptmann Moritz was immediately ordered to move the unit some 30 miles (48 km) northwards to Schwaighofen, near Ulm.

During the next eight days at Schwaighofen IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 saw little action. The time was taken up mainly in making good the recent losses suffered in pilots, groundcrews and machines. On 27 July 10. Staffel celebrated the announcement of the Gruppe’s second Knight’s Cross, awarded to their recently wounded Kapitän, Oberleutnant Hans Weik, for his 36 kills to date. Two days later the Sturmgruppe was back in action when the Eighth Air Force again struck at oil industry objectives. The target for nearly 600 heavily escorted B-17s was the Leuna synthetic-oil plant near Merseburg. It was this force which Hauptmann Moritz and his men attacked (in the company of JG 300’s two Bf 109 Gruppen).

Of the 13 US aircraft brought down in the resulting action near Leipzig, seven (six B-17s and a P-51) were credited to pilots of 2./JG 51. This Staffel also suffered the single loss of the day, but one of the Fortresses had provided Kapitän Oberleutnant Horst Haase with his half century. At least three of the remaining six victories went to ex-Sturmstaffel 1 veterans – Willi Maximowitz got a B-17, with Werner Gerth and Wolfgang Kosse claiming a P-51 each. With his score now standing at 24, Feldwebel Kosse was still working hard for his rehabilitation!

To indicate their unique close-in role within the Defence of the Reich organisation, many of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s pilots took to wearing ‘Whites-of-the-Eyes’ insignia on their leather flying jackets. This pair is modelled by 10. Staffel’s Feldwebel Hans Schäfer, whose final tally of 27 kills included eight heavy bombers

Twenty-four hours later it was the turn of the Fifteenth Air Force to target Axis oil. The pilots of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 were sent up on their own against the bombers, which were reported to be heading for Hungary. They did not find the B-24s, which attacked the Lispe oil refinery complex without opposition. They did, however, sight a formation of B-17s whose objective was Budapest-Duna airfield. But the Focke-Wulfs were unable to penetrate the Fortresses’ strong fighter screen. Instead, it was the aggressive P-38 pilots who broke up the Sturm assault.

In the ensuing free-for-all, the Gruppe was credited with a trio of Lightnings, all three downed in the area of Lake Balaton. In return, the P-38s claimed four of the Sturmböcke. IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s actual losses were two pilots severely injured – 2./JG 51’s Leutnant Siegfried Schuster when attempting an emergency landing in his badly shot-up machine, and Feldwebel Willi Maximowitz, whose Focke-Wulf somersaulted on landing back at Munich-Neubiberg.

On 31 July the Gruppe transferred down to Schongau, close by the Austrian border. This put them right in the path of the Fifteenth Air Force’s ‘heavies’, attacking targets in southwest Germany. But when the next such raid came in – a combined strike against industrial plants and marshalling yards in the Friedrichshafen-Innenstadt areas on 3 August – bad weather prevented Moritz’s pilots from making an early interception.

Having scrambled from Schongau shortly after 1030 hrs, the Gruppe, escorted by the Bf 109s of I./JG 300, spent the best part of an hour searching for the enemy bombers. When they eventually found a box of some 30 B-24s (little more than 32 miles (51 km) from their point of takeoff!), the Americans were already heading out across the Alps on their way back to base. A determined Sturm assault hacked down 19 of the Liberators in just six minutes (it is now believed that the 465th BG in fact lost 11 of their number to this attack). But these successes had not come cheaply. Nine Focke-Wulfs were shot down, with five pilots killed, one missing and one wounded. And the day’s activities were not over yet.

In a telling demonstration of the weight and scope of the aerial assault now being waged against the increasingly beleaguered Reich, that same afternoon saw a force of almost 350 heavily escorted B-17s of the UK-based Eighth Air Force also despatched to strike at targets in southwest Germany. After the depredations of the morning, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 could put up only six fighters to meet this new threat. One was shot down north of Strasbourg by return fire from the bombers, its pilot parachuting to safety. The other five were credited with the destruction of a Fortress each.

Never again would the Gruppe be able to claim two-dozen heavy bombers downed in a single day. During the remaining nine months of the war its pilots would top the 20-mark just three more times. Against this, their casualty rates would continue to climb steadily; and one of the blackest days in the unit’s entire history was now less than a week away.

The main weight of the Eighth Air Force’s attacks of 9 August was directed against transportation targets in southern and southwestern Germany. Having recovered from its mauling of six days earlier, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 put up a maximum effort in response. But on this occasion it was prevented from getting through to the bombers by the strong advance screen of US fighters flying ahead of the stream.

About 100 P-51s bounced the Gruppe from out of the sun as it flew in its usual broad arrowhead north-westwards across the Black Forest towards the oncoming Fortresses. There was no question of following the original Sturm edict that ‘losses on the approach flight are to be compensated for by closing up on the leader’. The formation was scattered far and wide, and it was every man for himself. They were lucky to get away with just three pilots killed and one wounded.

Only two Focke-Wulfs managed to fight their way past the advanced screen and through the close escort to get at the bombers, where they claimed a B-17 apiece. Both were flown by experienced Staffelkapitäne. One was Oberleutnant Ekkehard Tichy, who had taken over 10./JG 3 after the wounding of Hans Weik three weeks earlier. Tichy had himself been severely injured back in March when, as Kapitän of 9./JG 3, the canopy of his Bf 109 had been shattered by return fire from the Fortress he was attacking and he had lost the sight of one eye. The other successful claimant was 11. Staffel’s Leutnant Werner Gerth, who was also to be credited with a P-51 on this date.

The Mustangs had not finished with the Gruppe yet, however. Unnoticed, about 40 P-51s were tailing the Sturmböcke, which had reformed and were now heading back to Schongau. As they broke ranks to land, the USAAF fighters pounced. Seven more Fw 190s were shot down, with a further five pilots being killed and another two wounded.

9 August 1944 had, admittedly, been a particularly hard day for IV.(Sturm)/JG 3. But the ever-increasing strength of the opposition it was facing, the frequency and ferocity of the enemy’s attacks and its own declining successes, coupled with the growing losses, was a situation that was being reflected throughout the entire Defence of the Reich organisation. The fears for the future once expressed by Major von Kornatzki were becoming a reality. The Americans had not been given a ‘knockout blow’, and the Luftwaffe’s fighters were now in imminent danger of being overwhelmed by sheer weight of numbers.

The OKL sought desperately to remedy the situation. It had already pared other fronts to the bone to bolster the homeland’s internal defences, so there was little further help to be had from that quarter. Furthermore, the USAAF’s long-term offensive against the Reich’s oil industry was beginning to make itself felt, although not yet among frontline units – the days of conserving every last drop of precious aviation spirit by harnessing ox teams to tow aircraft, rather than taxiing them about the field under their own power, were still some way off. However, at the training schools flying hours were being curtailed and courses shortened to keep up the flow of new pilots (despite the latter arriving in the frontline woefully ill-prepared) that were needed to make good the escalating rates of attrition.

One of the High Command’s answers to this vicious circle was to increase the establishment of existing Jagdgruppen from three Staffeln to four. JG 3 underwent such reorganisation on 10 August. This meant that IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s three component Staffeln, hitherto numbered 10., 11. and 12., were redesignated and would henceforth operate as 13., 14. and 15. respectively. And the attached 2./JG 51, which had served for weeks past as a quasi-fourth Staffel within the Gruppe, was now officially taken on strength as 16.(Sturm)/JG 3.

It was in this new form, and in the company of the Luftwaffe’s second Sturmgruppe, that Hauptmann Moritz’s IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 flew its next mission five days later.