It was in the immediate aftermath of the Oschersleben battle that the Luftwaffe’s second Sturmgruppe had been formed. Perhaps not surprisingly, the unit selected to undergo conversion was the Fw 190 equipped II. Gruppe of Major Walther Dahl’s JG 300.

From its base at Unterschlauersbach, II./JG 300, then under the command of Major Alfred Lindenberger, had been the second most successful Gruppe in action on the day of Oschersleben. In the engagement over the Halberstadt-Quedlinburg area, it had been credited with 14 ‘heavies’ and a pair of P-38s destroyed at the cost of three of its own pilots wounded. In the five-and-a-half weeks since that 7 July, II./JG 300 had been combining Sturm training with its operational commitments (in three days alone, 18-20 July, it had claimed 22 US bombers and ten fighters destroyed).

The Eighth Air Force’s objectives on 15 August were Luftwaffe airfields in western Germany and the occupied Low Countries. The specific targets for the 200+ B-17s of the 1st Bomb Division were three fields at Cologne, Frankfurt and Wiesbaden. It was this force that the two Sturmgruppen were sent up to intercept.

At around 1000 hrs the Focke-Wulfs scrambled from Schongau and Holzkirchen (II.(Sturm)/JG 300 had transferred from Unterschlauersbach to the latter base on 13 July) and set off on the long haul north-westwards, escorted by the Bf 109s of I. and III./JG 300. It was a perfect summer’s day, with hardly a cloud in the sky and almost unlimited visibility. Some 90 minutes later, just after crossing the Moselle valley, the fighters sighted the oncoming American formation in the far distance. Major Dahl who, as Kommodore of JG 300, was leading the Gefechtsverband (battle group) ordered a wide turn to port to enable the two Fw 190 Gruppen to get into position for a stern attack.

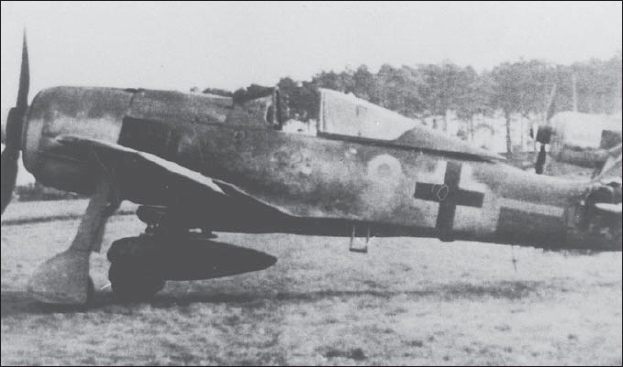

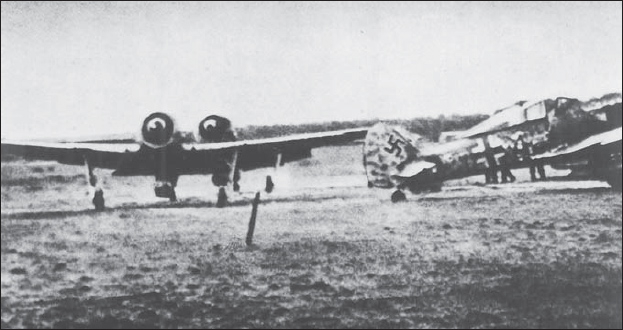

From the same Fieseler manufacturing block as ‘White 5’ seen in the top photograph on page 76, Hauptmann Moritz’s Sturmbock Wk-Nr. 681382 – complete with ‘blinkers’ – displays IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s new ‘anonymous’ finish minus the black cowling and white aft fuselage band at Schongau in August 1944

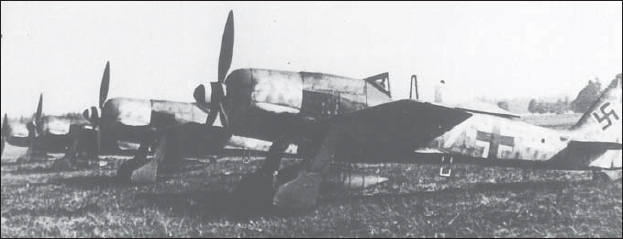

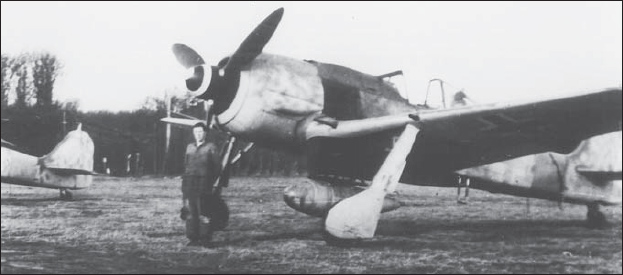

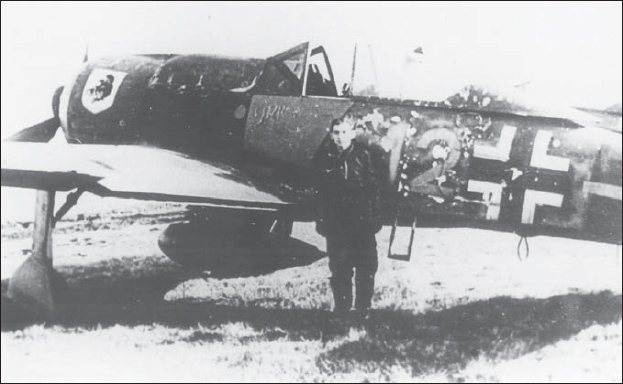

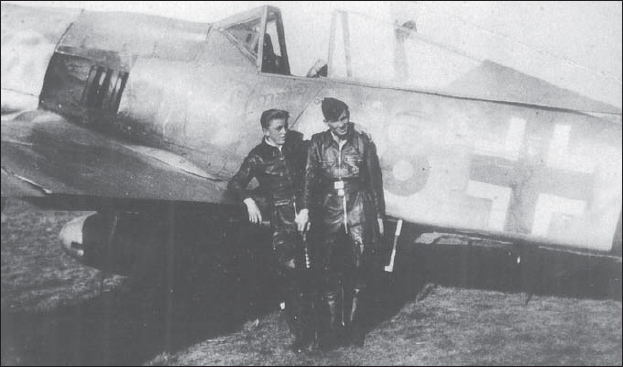

These Sturmböcke of II.(Sturm)/JG 300 were photographed at Holzkirchen in late August 1944 at the start of their new career. The pilot snatching 40 winks in the shadow of ‘White 5’ (above) is Unteroffizier Friedrich Alten, who would go down in this machine (Wk-Nr. 681366) near Kassel on 11 September

Selecting a box of Fortresses temporarily devoid of its close escort of P-51s, the Sturmböcke bored in with all cannon blazing. Honours were almost exactly even – ten B-17s credited to the veteran IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 and nine to the tyros of II.(Sturm)/JG 300. In exchange for these 19 Fortresses (according to US sources this figure is more than double the number of bombers actually shot down, although it is still well below the astronomical 84 claimed by Dahl in his post-war ‘Rammjäger’,which includes seven shared among the six Fw 190s of his Geschwaderstab flight!) the Gefechtsverband lost six pilots killed and two wounded and twelve fighters destroyed. Most of the casualties were suffered by I./JG 300 in dogfights with the escorting P-51s.

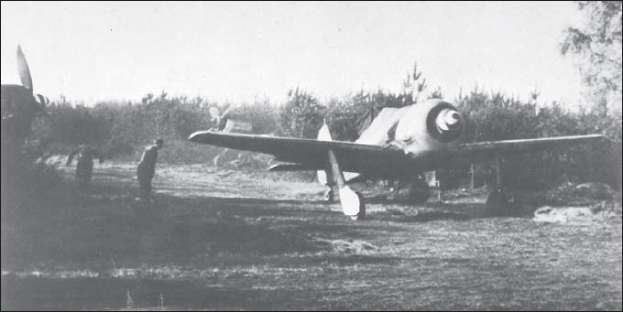

After the action, Hauptmann Moritz’s pilots were ordered to land at Frankfurt-Eschborn, where they would remain for the next few days as a precaution against further US raids on targets in the Rhine-Main regions. The Fw 190s of II.(Sturm)/JG 300 landed where they could to refuel before the long flight back to Holzkirchen. One group of about a dozen, red fuel lights already beginning to wink, lobbed down in desperation on a small grass field just to the north of the Moselle, only to discover that it was being used solely for glider training. After a six-hour wait in the hot afternoon sun, a small amount of aviation fuel was trucked in – just enough for the Focke-Wulfs to make the short hop to a nearby fighter base, where they could refuel and re-arm properly.

These Sturmböcke of II.(Sturm)/JG 300 were photographed at Holzkirchen in late August 1944 at the start of their new career. The pilot snatching 40 winks in the shadow of ‘White 5’ (above) is Unteroffizier Friedrich Alten, who would go down in this machine (Wk-Nr. 681366) near Kassel on 11 September

Even with almost empty tanks and ammunition magazines, it would be a tight squeeze getting out of the pocket handkerchief-sized field. One pilot can still recall the heavy Sturmböcke ploughing through the metre-high grass before being yanked off at the very last moment, their wheels just missing the glider school’s flight hut. All made it safely, eventually arriving back at Holzkirchen 11 hours after the morning scramble.

Creditable though the two Sturmgruppens’ performance had been, it still fell far short of the ‘decisive blow’ for which they had been intended and which, it was hoped, they might yet deliver. But even if 19 enemy bombers had been brought down on 15 August, it was a casualty rate the now ‘Mighty Eighth’ could accept and absorb. It would certainly not discourage the Americans from continuing their ongoing daylight bombing campaign against the Reich’s military and industrial strength.

The following day brought a decidedly less impressive result. Of more than 1,000 ‘heavies’ despatched against oil and aviation targets throughout central Germany, just eight fell to Sturm assault. All but one were claimed by IV.(Sturm)/JG 3, which also suffered the sole fatality. Whether by accident or design, the one-eyed Oberleutnant Ekkehard Tichy collided with one of the 91st BG Fortresses under attack and both bomber and fighter went down. The Staffel that Tichy had commanded for less than a fortnight (the ex-10., now 13.(Sturm)/JG 3) passed into the capable hands of Leutnant Walter Hagenah. Tichy himself would be honoured with a posthumous Knight’s Cross on 27 January 1945. Eleven of his 25 victories (including the last) had been four-engined bombers.

On 19 August the Fw 190s of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 were ordered back from Frankfurt to Schongau. But they were soon on the move again. Forty-eight hours later they were sent to Götzendorf – a field just to the southeast of Vienna – in the expectation of renewed activity in that area by the Fifteenth Air Force.

‘Black Double Chevron’ kicks up dust (far right) as Hauptmann Moritz starts to roll. Note that ‘Black 12’ on the left still retains its black nose and ‘lightning flash’ paint job

Luftwaffe intelligence was good. On 22 August a large force of B-24s did indeed lift off from their Italian bases to attack oil industry targets around the Austrian capital, including the underground storage facility in the Lobau district. With almost the entire Eighth Air Force anchored to the ground in the UK by bad weather, the Luftwaffe put up a maximum local effort – nine Gruppen in all – against this threat from the south.

Forming the spearhead of the defensive response, the two Sturmgruppen, accompanied on this occasion by I./JG 300 and I./JG 302, met the B-24s close to the Hungarian border some 80 miles (130 km) to the southeast of Vienna. In the attack that followed, 15 Liberators reportedly went down, with Hauptmann Moritz’s ‘Old Hares’ again claiming just one more than the still relatively inexperienced pilots of II.(Sturm)/JG 300.

After hurriedly landing to refuel and re-arm, the Sturm units were sent back up to try to catch the bombers on their return flight. They failed to find the B-24s, but each Gruppe claimed a B-17 from another Fifteenth Air Force formation that was heading back through the same area. In addition, II.(Sturm)/JG 300 ended the day with four P-38s added to its scoreboard.

Good the Luftwaffe intelligence service may have been, but it obviously was not infallible. IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 had returned promptly to Schongau, only to be scrambled again shortly after 1000 hrs the following morning when strong enemy formations were again reported to be heading for the Vienna region. As the Focke-Wulfs set course eastwards, they were joined by II.(Sturm)/JG 300. But the only escort the two Sturmgruppen had was the half-dozen machines of Major Dahl’s Geschwaderstab flight.

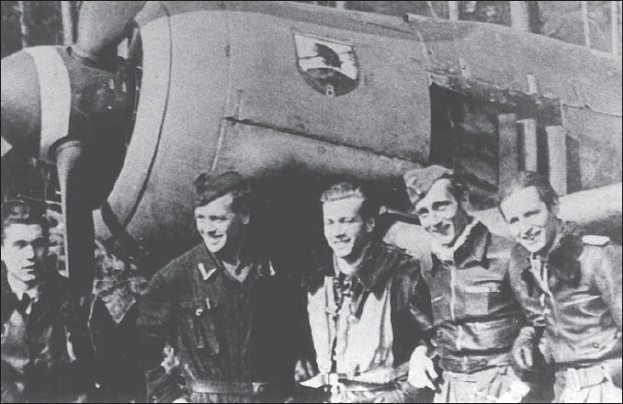

On 22 August the wounded Oberleutnant Hans Weik, walking with the aid of a stick and with his right arm still in a sling, visited his old 10. Staffel at Schongau to celebrate with them his recently awarded Knight’s Cross. On Weik’s immediate left may be seen Leutnant Walther Hagenah and Feldwebel Hans Schäfer

At Lobnitz a mechanic of 8.(Sturm)/JG 300 leans into the cockpit to make some final adjustments . . .

. . . before the pilot runs up the engine prior to take-off. On the right, Staffelkapitän Leutnant Spenst walks forward to deliver a few last-minute instructions of his own. Note that the unit is now sporting red Defence of the Reich bands

The mission completed – probably just an air test, as the drop tank is still in situ – the unknown pilot comes back in for a neat three-pointer

Another ‘black man’ (Luftwaffe jargon for the ground mechanics in their dark working overalls) stands ready in front of his charge, awaiting the pilot’s arrival

This time contact was made south-southwest of the Austrian capital. Hauptmann Moritz led his pilots in two separate assaults on an unescorted box of B-24s (machines of the 451st BG on their way to bomb Markersdof airfield). ‘Emerging from cloud cover six to ten abreast and coming in with all cannons firing’, in the words of one Liberator crewman, the Fw 190 pilots downed five B-24s on their first pass and added another four in the second attack three minutes later. One of the latter fell to Moritz himself. This ties in exactly with the nine losses suffered by the 451st BG, and proved to be one of the last big blows inflicted by Luftwaffe fighters on Fifteenth Air Force bombers during the closing months of the war.

In return, the B-24 gunners had claimed 29 of the Focke-Wulfs destroyed or damaged. Although this figure was a gross overestimate, the actual losses suffered by the Gruppe were bad enough – four pilots killed and a fifth missing.

‘Yellow 9’ of 6.(Sturm)/JG 300 was used by Feldwebel Hannes Theiss to claim ten kills, including five fourengined bombers

6. Staffel pilot Feldwebel Ewald Preiss is pictured in the cockpit of his ‘Yellow 1’, which bears the name Gloria. Ewald Preiss would not survive the war, being one of the seven 6.(Sturm)/JG 300 losses suffered on 24 March 1945

IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 had been able to go after the bombers practically unhindered. This was due in no small part to the escorting P-51s concentrating their attentions almost entirely on II.(Sturm)/JG 300. The latter unit also sustained at least five known fatalities, but was credited with an equal number of Mustangs shot down.

The Sturmgruppen would be sent up against the Fifteenth Air Force on at least five more occasions before the month was out. On 24 August a mixed force of B-17s and B-24s attacked oil refineries in southern Germany and Czechoslovakia. The two Gruppen claimed five B-24s between them, but each suffered one pilot killed and one wounded. Twenty-four hours later, when the Fifteenth Air Force targeted airfields and aircraft factories in the Brno and Prostejov regions of Czechoslovakia, the Sturmgruppen failed to score a single kill, while losing five pilots.

Shortly after 0900 hrs on 29 August, about a dozen machines of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 lifted off from Jüterbog, south of Berlin (where they had been on temporary detachment for the last two days), and set course southeastwards for the Czech border, accompanied by the Bf 109s of III./JG 300. En route they were joined by the rest of Major Dahl’s Geschwader. After a good 90 minutes, and when over the foothills of the Carpathians, this Gefechtsverband sighted a heavily escorted formation of B-17s. The two Sturmgruppen pressed home their attacks. IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 claimed four of the bombers – believed to be from the 2nd BG – but lost a pilot, who went down over Trencin, Slovakia. II.(Sturm)/JG 300 also claimed four Fortresses, plus an additional pair of Herausschüsse, without loss.

To all intents and purposes this was the end of the Sturm campaign against the Fifteenth Air Force in southern and southeastern Europe. The Sturmböcke had inflicted some telling losses on the ‘heavies’ flying up from Italy, but that all-important ‘decisive blow’ still eluded them. The bombers of the Fifteenth Air Force, like their UK-based counterparts of the Eighth, were benefiting from ever stronger and more effective fighter protection. If the enemy’s escorting fighters could break up the Sturmgruppens’ carefully co-ordinated approach runs, then Major von Kornatzki’s original concept of a concerted, mass attack would become increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to implement.

Nevertheless, the Sturm pilots, until overtaken by events on the ground, would continue to give of their best as they tried to carry out their own unique role in the daylight defence of the Reich. For the next three months their major battleground would be central and western Germany, and their main opponents the bombers and fighters of the Eighth Air Force. With their own numbers bolstered by the entry into service of a third (and final) Sturmgruppe, they would demonstrate that, when conditions were right, they were still a force to be reckoned with.

On 30 August IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was ordered to vacate Schongau, in deepest Bavaria, for Schafstädt, an airfield some 110 miles (180 km) to the southwest of Berlin. It was at this time too that II.(Sturm)/JG 300 departed Holzkirchen for Erfurt-Bindersleben, half as far again from the German capital. For the two Gruppen, the first week or so at their new bases was to remain relatively quiet.

Another 6. Staffel Sturmbock taxies out from its concealed dispersal in a stand of young firs in the early autumn of 1944

Meanwhile, the long-awaited third Sturmgruppe was at last approaching the end of a protracted and costly period of working-up. This unit, II.(Sturm)/JG 4, was formed primarily around a cadre of pilots and groundcrews from a now defunct Zerstörergruppe that had previously been based on the French Atlantic coast. After converting from their twinengined Junkers Ju 88s on to Fw 190s at Hohensalza, the ex-Zerstörer pilots moved to Salzwedel to join the new Gruppe – which had officially been brought into being on 12 July 1944 – to commence Sturm training.

They could not have wished for a better Kommandeur to oversee their transition than the ‘Father of the Sturm Idea’ himself, the now Oberstleutnant Hans-Günter von Kornatzki. Eager to see that his new command be given the best possible chance to put his ‘massed stern assault’ tactics into practice, von Kornatzki had also gathered around him a nucleus of original Sturmstaffel 1 pilots. Among them was Oberleutnant Ottmar Zehart, who had scored the very first Sturm victory of all, and he now became the Kapitän of 7.(Sturm)/JG 4.

After suffering at least two pilots killed and several injured during training, II.(Sturm)/JG 4 moved to Welzow on 31 August. Situated roughly the same distance to the southeast of Berlin as Schafstädt was to the southwest, Welzow was a large tree-girt landing ground quite capable of accommodating the Gruppe’s full complement of 70+ Sturmböcke.

The three Sturmgruppen were now in place and awaiting the next major incursion by the Eighth Air Force.

It came on 11 September. Mission No 623 saw the despatch of over 1100 heavy bombers, escorted by more than 400 fighters, against a whole range of targets including eight synthetic-oil plants and refineries, an ordnance depot and engineering facilities. The Luftwaffe responded with practically all it had – more than a dozen Jagdgruppen totalling over 500 fighters. The Sturm units formed the defenders’ main strike force, with two experienced Gruppen, their recent losses made good, plus a third (as yet unblooded, but at full strength and under expert leadership) thrown into action against the ‘heavies’. Each had its own Bf 109 fighter escort. Had the day of the ‘Big Blow’ finally arrived?

The two westernmost Gruppen, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 and II.(Sturm)/JG 300, took off first, both scrambling shortly after 1040 hrs. Led by Major Dahl’s Stabsschwarm, and covered by I./JG 300 and I./JG 76, the formation was vectored south-westwards towards a large force of B-17s reported to be in the Eschwege area. Hardly had the enemy been sighted – some miles to the southeast over Eisenach – before the Focke-Wulfs of II.(Sturm)/JG 300, maintaining close formation and at an altitude of some 16,500 ft (5000 m), were pounced upon from above by a horde of higher-flying Mustangs.

The tight formation disintegrated into a violent free-for-all as the heavy Sturmböcke, all hopes of attacking the Fortresses dashed, sought to protect themselves from the lethal attentions of the Mustangs. It was hardly an equal contest. Although the survivors claimed an optimistic eight P-51s shot down, the Gruppe quickly lost ten pilots killed and two wounded.

Meanwhile, Major Dahl’s Stab flight, together with IV.(Sturm)/JG 3, had managed to avoid the fray over Eisenach and were chasing back north-eastwards after another large group of Fortresses which had just bombed the Merseburg-Leuna synthetic-oil complex. They caught up with the enemy 30 minutes later just short of Halle. Manoeuvring into position behind and slightly below one of the bomber boxes, the Focke-Wulf pilots adjusted their speed to that of the retiring B-17s. At a range of 220 yards (200 m) they opened fire, boring in to within feet of their selected targets before breaking off and diving away.

Machines of II.(Sturm)/JG 300 are lined up at readiness at Löbnitz in September 1944. The parade-like formation seems to suggest that there is no fear of attack from the air . . .

Machines of II.(Sturm)/JG 300 are lined up at readiness at Löbnitz in September 1944. The parade-like formation seems to suggest that there is no fear of attack from the air . . .

Sixteen Fortresses – most believed to have been from the 92nd BG – were reported to have gone down. Three fell to Major Dahl and his Schwarm and the remaining 13 were claimed by pilots of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3. But the latter were not to escape scot-free. The ubiquitous Mustangs were soon on the scene, and now it was the Sturmböcke who had to defend themselves. 14. Staffel’s Leutnant Werner Gerth was credited with a single P-51 (which, together with one of the B-17s just downed, took his Sturm total to 25), but the Gruppe lost three pilots killed and two wounded.

And what of II.(Sturm)/JG 4? After more than an hour at cockpit readiness, some 50+ Focke-Wulfs were scrambled from Welzow. Rendezvousing with their III./JG 4 escorts over Finsterwalde, the Gruppen then spent a good two hours following ground control’s directions, which gradually led them south-southwest until, shortly after midday, they finally sighted a mass of contrails close to the Czech border. These betrayed the presence of B-17s forming part of the 3rd Bomb Division force sent to attack refineries at Chemnitz, Rurhland and Brüx.

. . . but once in the air, it was a different matter. Here, the end of yet another Fw 190 is captured by the gun-camera of a pursuing US fighter – and is that odd Y-shaped form near the bottom left corner of the film still the pilot making good his escape?

At 26,000 ft (8000 m) the pilots of II.(Sturm)/JG 4 curved in towards the bomber stream, most apparently aiming for the unprotected low formation of one of the trailing boxes. Despite their inexperience, they caused carnage among the Fortresses, being credited with 11 destroyed (a figure which tallies exactly with the losses suffered by the Ruhrlandbound 100th BG). But, as ever, the escorting P-51s were quick to react, protecting the B-17s from further assault and downing several Focke-Wulfs before the rest broke off in search of a less well-defended target. They found one in another formation of Fortresses heading for Brüx. Twelve more bombers were claimed, including one rammed by 8. Staffel’s Leutnant Alfred Lausch, who lost his own life in the attack.

Oberfeldwebel Klaus Richter, seen here in the cockpit of his ‘Red 4’ (a fairly clean-looking Sturmbock complete with ‘blinkers’), often flew as Katschmarek (wingman) to 5. Staffel’s more experienced Unteroffizier Ernst Schröder

II.(Sturm)/JG 4’s first operation had thus brought the unit 23 victories (seven of them Herausschüsse). But the price paid was heavy, with 12 pilots killed and four wounded. Twenty-three Focke-Wulfs had been lost – nearly half of those engaged!

The following day’s press announcements spoke of an ‘outstanding defensive success’, with figures of 90 or more enemy bombers destroyed. Even the Americans admitted that it was the ‘first major aerial clash experienced since 28 May’. But, in reality, 11 September was a costly setback for the Reich’s Defence units. Some 113 fighters had been lost in combat against Mission No 623, and a total of 56 pilots had been reported killed or missing. The Sturmgruppen, despite all their efforts, had failed to deliver what was expected of them – not a single enemy bomber formation had been deflected from its assigned objective by their actions.

As if to demonstrate their superiority, the American bombers – nearly 900 in all – returned to many of the same targets 24 hours later. The three Sturmgruppen were again among the defenders sent up to challenge them. Operating together as part of the same Gefechtsverband as usual, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 and II.(Sturm)/JG 300 were vectored to the north of Berlin, where they hit the B-17 bomber stream hard. In two separate attacks IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was credited with seven Fortresses, but lost an equal number of Focke-Wulfs to the bombers and their escorting fighters, with three pilots being killed and two wounded.

On this occasion II.(Sturm)/JG 300 avoided the fighter screen long enough to get at the bombers as well, claiming a dozen of the B-17s. But it too lost three pilots, plus one wounded, in the day’s engagements.

Meanwhile, II.(Sturm)/JG 4, accompanied by the Bf 109s of III./JG 4 and I./JG 76, had been directed westwards, where another formation of B-17s was reported to be heading towards Magdeburg. The Fw 190 pilots were unable to repeat their success of the previous day, but nonetheless claimed the destruction of eight Fortresses (one falling to the Kommandeur himself), together with five Herausschüsse. In return they lost eight aircraft, suffering four pilots killed and a fifth wounded.

One of the fatalities was Oberstleutnant Hans-Günter Kornatzki. His machine having been damaged during the attack on the bombers, the Kommandeur attempted a forced landing to the southwest of Magdeburg (ironically, not far from Oschersleben, the scene of the Sturm force’s most publicised encounter with the enemy). Just before touchdown, however, von Kornatzki’s ‘Green 3’ clipped some high-tension cables and cart-wheeled into the ground.

The loss of the ‘Father of the Sturm Idea’ was an undeniable psychological blow to all, and to none more than the members of his own fledgling Gruppe. II.(Sturm)/JG 4 had claimed the most Sturm victories in each of the two recent actions, but at a terrible cost in human and material terms. Nearly a third of its pilots had been killed or wounded, and over half of the 61 Sturmböcke that had flown into Welzow just 12 days earlier were now destroyed. This was a rate of attrition that no unit, let alone an inexperienced one, could be expected to bear.

Oberstleutnant von Kornatzki’s place at the head of the Gruppe was assumed by Hauptmann Gerhard Schroeder, the Kapitän of 8. Staffel. But it would take some time to assimilate the many new pilots and replacement machines needed to bring II.(Sturm)/JG 4 back up to full operational readiness, and it was to be the end of the month before the unit flew its next Sturm mission.

As an interesting sidelight, while these newcomers to Welzow were being initiated into the procedures required for a successful Sturm assault, many of the survivors of the last two such attacks were intent on putting the experience behind them in time-honoured military fashion. So much so that the station commander at Erfurt-Bindersleben was forced to confine all personnel of II.(Sturm)/JG 300 to camp. One of the reasons given for this Draconian measure was the ‘impossible behaviour’ of the troops in local watering holes and other public establishments. Nor did the complaints of the surrounding civil population end there. It is said that when the Gruppe departed for Finsterwalde on 26 September, they left 20 pending paternity suits behind them!

The latter half of September had been a relatively uneventful period (at least in the air) for the other two Sturmgruppen as well. This was due mainly to a combination of bad weather and the Eighth Air Force diverting at least part of its energies to the support of the Anglo-American airborne landings along the river lines between Eindhoven and Arnhem in Holland (officially known as Operation Market Garden, but now much more widely known as the ‘Bridge Too Far’).

The operational lull did, however, allow both Walther Dahl and Wilhelm Moritz to be summoned (separately) to Hitler’s ‘Wolf’s Lair’ HQ in East Prussia to report personally to the Führer on the activities of the Sturmgruppen thus far and, presumably, to be asked their views on the road ahead in light of the recent loss of Oberstleutnant von Kornatzki.

Whatever decisions, if any, were arrived at, 27 September would, for the first time, see all three Sturmgruppen operating together in a single Gefechtsverband. The Eighth Air Force’s objectives on that day included transportation networks and war plants in western Germany; and it was against the 2nd Bomb Division’s B-24s, targeting the Henschel works in Kassel (producers of the much-feared Tiger tank), that the first massed Sturm assault would be directed.

IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 scrambled from its temporary base at Alteno at 1000 hrs. After rendezvousing with the other Gruppen (including I./JG 300, whose Bf 109s were to fly cover), the entire formation set course for Kassel. Some 45 minutes later contact was made with part of the attacking force to the southwest of the target area. The Gefechtsverband had chanced upon the ‘wandering’ 445th BG, which, having become separated from the main bomber stream, had opted for Göttingen as a target of opportunity and was now heading back out over Eisenach.

The three Sturmgruppen hit the unescorted Liberators in turn. The first to attack was IV.(Sturm)/JG 3. Flying their customary broad arrowhead with Hauptmann Moritz at the point, the pilots bored in close before splitting into Staffeln, their heavy 30 mm cannon cutting swathes through the hapless Liberator formation. In just three minutes they had claimed a staggering 17 B-24s destroyed, plus a further four Herausschüsse. Their own casualties amounted to just five pilots wounded.

Aircraft of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 taxi out at Alteno for the mission of 27 September 1944. All three Sturmgruppen were in action against an unescorted formation of B-24s on this date, with IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 being the first to attack. They claimed 21 Liberators . . .

Next to go in was II.(Sturm)/JG 300. The Liberator gunners were fighting for their lives. The Gruppe’s 21 claims (a third of them Herausschüsse) cost it seven pilots killed, the sky now a tumult of burning and exploding aircraft. One surviving B-24 pilot recalled the scene. ‘At one moment I saw four German fighters and five of our own bombers going down around me. It was indescribable’.

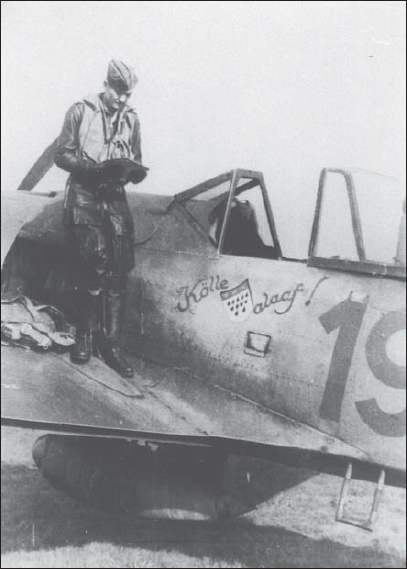

. . . next to go in were II.(Sturm)/JG 300, which was also credited with 21 B-24s. Two of the bombers fell to Unteroffizier Ernst Schröder, seen here on the wing of his famous Kölle alaaf!. Lastly, . . .

One of the assailants, 5.(Sturm)/JG 300’s Unteroffizier Ernst Schröder, was more graphic in his description of the bloody clash high over Eisenach;

‘As we approached in close formation we could see the results of the first wave’s attack – some bombers on fire, others blowing up. My Staffelkapitän and I had a new type of experimental gyroscopic gun-sight fitted in our fighters. This enabled me to claim two B-24s within seconds of each other.

‘When I hit the first it immediately flipped over onto its side and went down. Its neighbour was already damaged, the two left-hand engines pouring smoke. The new sight allowed me to line up on him almost instantly. Another short burst and he was enveloped in flames. I flew alongside him for a moment, staring at the long banner of fire streaming back beyond his tailplane. Then this great machine slowly turned over onto its back before it too plunged earthwards.’

By this time a group of P-51s that had been escorting a formation of 1st Division B-17s near Cologne, some 100 miles (180 km) away to the east, and had picked up the Liberators’ calls for assistance when they first spotted the approaching mass of German fighters, were finally beginning to arrive on the scene – four minutes after IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s first unopposed pass.

Despite their belated appearance, the Mustangs may have been responsible for some of II.(Sturm)/JG 300’s losses. They certainly inflicted heavy casualties on the reconstituted II.(Sturm)/JG 4, whose pilots were in the last of the three waves to go in. The Gruppe’s subsequent claims for 25 B-24s destroyed, plus a further 14 Herausschüsse, are patently wide of the mark (the bomber formation was never that large to start with, let alone after the first two attacks!), but the inexperience of many of the pilots in this, their baptism of fire, should perhaps be taken into account.

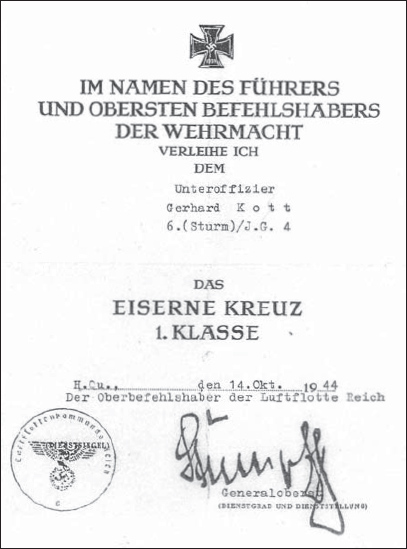

There are fewer uncertainties about the unit’s casualties. At least 13 of its Sturmböcke were hit, and seven pilots were reported killed or missing, with another three wounded. Nor were the losses restricted to the ranks of the replacements, for among the missing was arguably one of the most experienced Sturmpiloten of all – the veteran Staffelkapitän of 7.(Sturm)/JG 4, Oberleutnant Ottmar Zehart. His wingman that day was Obergefreiter Gerhard Kott, who recalled;

‘After our first pass we wanted to re-form for a second attack. But hardly had the Gruppe got itself into some sort of formation before I saw Zehart’s machine rapidly losing height. He was later posted as missing.’

And Ottmar Zehart, whose ‘Yellow 2’ went down somewhere near Brunswick, remains missing to this day.

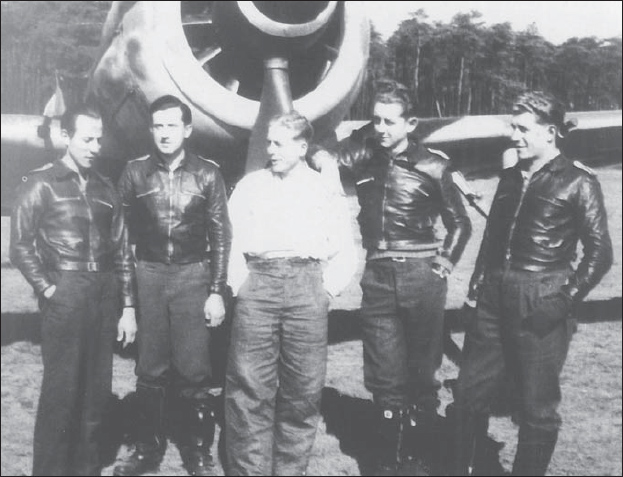

. . . it was the turn of II.(Sturm)/JG 4. Its pilots claimed the destruction of a staggering 39(!) Liberators. The five NCO pilots of 5. Staffel pictured here, from left to right, are Unteroffiziere Barion and Chlond, Feldwebel Berg and Unteroffiziere Keller and Erler. They accounted for nine bombers between them

II.(Sturm)/JG 4’s haul of Liberators cost it seven pilots killed or missing. Obergefreiter Gerhard Kott, pictured here, was flying wingman to Oberleutnant Ottmar Zehart, and witnessed the Kapitän of 7. Staffel go down

The Sturmgruppen’s claims for a total of 81 Liberators (plus six Mustangs) are, of course, exaggerated. But there is no denying the fact that they had inflicted grievous wounds upon the 445th BG. With 26 of its 37 B-24s failing to return, this represented the largest loss by any single USAAF group on any single mission during the entire war.

But not even a massacre on this scale could halt the juggernaut that the Eighth Air Force had by now become. Twenty-four hours later the 2nd Bomb Division sent its Liberators back to Henschel’s Kassel plant. This time, however, the Sturmgruppen were engaged elsewhere – against the B-17s of the 1st Bomb Division, targeting Magdeburg.

In a rerun of the previous day’s action, all three Gruppen concentrated in turn on a single box – the Fortresses of the 303rd BG (see Osprey Aviation Elite Units 11 – 303rd Bombardment Group for further details). II.(Sturm)/JG 4 went in first, followed by IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 and with the Stabsschwarm and II.(Sturm)/JG 300 bringing up the rear. The results were more modest, with 29 B-17s being claimed (the 303rd actually lost 11) before the Sturmböcke were set upon by US fighters. In the course of individual dogfights spreading over a wide area, the heavy Fw 190s claimed a single P-51 and a pair of P-38s (the latter not substantiated by post-war records).

Gerhard Kott was another of 27 September’s claimants. On 14 October he received the Iron Cross, 1st Class, for a total of five fourengined bombers shot down (the first while serving with IV.(Sturm)/JG 3. The award certificate, signed by Generaloberst Stumpff, GOC Luftflotte Reich, is reproduced here

5. Staffel’s Oberfähnrich Franz Schaar – pictured here perched on the cockpit sill of his Fratz III, victory stick in hand – was one of II.(Sturm)/JG 4’s three wounded of 27 September

The loss of 12 aircraft, while representing well over 100 personal tragedies, was something the ‘Mighty Eighth’ could take in its stride. But the 17 pilots and 22 machines lost to the Sturmgruppen on this 28 September was yet more bloodletting they could ill afford. The brief employment of a ‘Big Wing’ of all three Sturmgruppen operating together had not proved a success. Utilising their combined resources to maul one box of bombers, however savagely, was not going to prevent the rest of the huge enemy streams from continuing on to their assigned objectives. In the process, the Luftwaffe defenders were inevitably losing the war of attrition. A change of plan was called for, and with it came the beginning of the end for the Sturmgruppen as specialised bomber-killer units.

On 29 September Major Heinz Bär, then the Geschwaderkommodore of JG 3, visited Moritz and his men at their temporary Alteno base. Unlike IV.(Sturm)/JG 3, Bär’s other three Gruppen had been retained in Normandy and on the western front. They had all suffered heavily in the retreat from France, and had only recently been withdrawn to the Reich for rest and re-equipment. Now, Bär informed Moritz, the Sturmgruppe was to be returned to the control of its parent Geschwader. A few days later IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 flew back to Schafstädt, thereby ending its long association with Major Walther Dahl’s JG 300.

Sturmstaffel 1 veteran Leutnant Walter Peinemann was one of 17 Sturm pilots killed on 28 September 1944, although unlike the vast majority of his comrades to die on this date, he did not fall in combat. Instead, he was killed in an accident whilst attempting to take off from Welzow in an Fw 190A-8/R2 from 7.(Sturm)/JG 4

The Gruppe’s first mission on its own could hardly be termed successful. On 6 October the Eighth Air Force’s B-17s mounted a twin-pronged attack on mainly industrial targets and military installations in northern Germany. Scrambling from Schafstädt shortly before noon, the Fw 190s of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 were directed northwards against the 400+ Fortresses of the 1st Bomb Division heading for towns and airfields in the Baltic coastal region. Before they could reach the bomber stream, however, they were intercepted by Mustangs south of Stettin. Two Sturmböcke were shot down, their pilots killed and many more aircraft damaged.

11.(Sturm)/JG 3’s Unteroffizier Gerhard Vivroux is seen here wearing a flying jacket adorned with the distinctive ‘Whites-of-the-Eyes’ emblem that was unique to the Jagdwaffe’s Sturm pilots. One of the most successful members of Sturmstaffel 1 with five kills to his credit, Vivroux had increased his tally to 11 by the time he was severely wounded in action during a clash with P-51s on 6 October. Suffering further injuries when he crashed landed his damaged fighter at Alteno, Vivroux finally succumbed to his wounds 19 days later

The rest of the Gruppe scattered, with a number of pilots subsequently putting down at Alteno due to a lack of fuel. Here, at least two more Focke-Wulfs were written-off in landing accidents. One pilot lost his life, while the other, already severely wounded in the clash with the P-51s, sustained further injuries. This was Feldwebel Gerhard Vivroux, formerly of Sturmstaffel 1, and one of the Gruppe’s most experienced members. He died in hospital just under three weeks later.

While IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 had been engaged up near the Baltic, the main weight of the Luftwaffe’s defensive response had been thrown against the B-17s of the 3rd Bomb Division attacking targets in the greater Berlin area. Among the units sent up to defend the capital was II.(Sturm)/JG 4.

After taking off from Welzow, the Fw 190s of the Sturmgruppe met up with III./JG 4’s Bf 109s over Finsterwalde, and together the two Gruppen set course north-westwards. They sighted the approaching enemy bomber stream between Brandenburg and Potsdam. Making a wide turn to get in behind the B-17s, they hit the Fortresses while they were still some 31 miles (50 km) short of their objective.

Even taking into account their recent propensity for overestimation, the Sturmgruppe’s claims for 22 Fortresses downed (seven of them Herausschüsse) marked another significant victory. But it was to be the last such major success for the Gruppe’s short-lived operational career as a true Sturm unit. And it had not come cheaply. Seven pilots had been killed and a further three wounded. Among the former was another of the original Sturmstaffel 1 veterans, Leutnant Rudolf Metz, whose ‘Green 2’ went down north of Brandenburg.

Little is known of II.(Sturm)/JG 300’s activities in the Berlin area on this 6 October, but it was back in the thick of things 24 hours later when the Eighth Air Force struck yet again at the Reich’s already sorely battered oil refineries. Among the eight Fortresses credited to the Gruppe near Merseburg was a unique treble for Leutnant Klaus Bretschneider, Staffelkapitän of 5.(Sturm)/JG 300, who brought down two B-17s with cannon fire and then added a third by ramming!

The other two Sturmgruppen were also aloft on 7 October as part of the Luftwaffe’s concerted attempt to protect what little remained of Germany’s vital oil industry. IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 matched II.(Sturm)/JG 300’s claims for eight B-17s destroyed, and managed to do so without loss (two of JG 300’s Sturm pilots had been killed). II.(Sturm)/JG 4 also suffered two fatalities, plus one wounded, in exchange for the seven Fortresses its pilots downed.

Two markings oddities carried by Sturmböcke of II.(Sturm)/JG 300, circa autumn 1944, but harking back to the Gruppe’s days as a ‘Wilde Sau’ nightfighter unit. Unteroffizier Paul Lixfeld of 6. Staffel poses in front of his very battered-looking ‘Yellow 12’, which clearly sports a rather large representation of the original boar’s head emblem of the ‘Wilde Sau’ units . . .

. . . while 8. Staffel’s crest, although featuring a spear-wielding (but altogether friendlier looking) boar trotting over a map of Europe, still provides him with a lantern to light the way

After the 23 B-17s (and single P-51) claimed on 7 October, the rest of the month was fairly quiet as far as the three Sturmgruppen were concerned. Although the Eighth Air Force kept up its attack on targets throughout the Reich, the ‘heavies’ were not subjected to Sturm assault. This was partly due to the increasingly parlous fuel situation, but also to the need for the three Gruppen to make good their recent losses in men and machines. One of JG 4’s Sturmstaffeln, for example, had by now been reduced to just four pilots, while II.(Sturm)/JG 300’s overall losses since June totalled 73 killed, two missing and 32 wounded!

All basic Sturm training was now being undertaken by a single Schulstaffel based at Liegnitz. But the replacement pilots were still far from combat ready when they arrived at their respective Gruppen, and a lot more practical instruction – or, at least, as much as the fuel supplies would allow – was required if they were to survive their first operational mission.

Fuel was scarce and pilot training barely adequate. The only thing there was no shortage of was aircraft. Despite all the Eighth Air Force’s efforts to bring Germany’s aviation industry to its knees, fighter production was to reach its all-time peak in the autumn of 1944. In the month of October, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 alone took delivery of no fewer than 56 replacement Fw 190s.

The main reason for the building up and conserving of forces, however, was the plan currently being formulated by General der Jagdflieger Adolf Galland for the ultimate ‘Big Blow’. This the Sturm units had so far failed to deliver. Now Galland planned to take the concept one stage further by using the entire fighter strength employed on Defence of the Reich duties in one massive, co-ordinated strike against the Eighth Air Force. If this could decimate a complete bomber stream, then the tables might yet be turned in the daylight battle for Germany’s skies – at the very least, it might gain sufficient time for the revolutionary new Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter (see Osprey Aircraft of the Aces 17 – German Jet Aces of World War 2 for further details) to be put into frontline service in significant numbers.

But the General der Jagdflieger’s strategy would never be put to the test. It was to founder on the twin rocks of interference from above and the demands of the war on the ground.

Another ‘Yellow 12’ of 6.(Sturm)/JG 300 was that flown by Fahnenjunker-Oberfeldwebel Lothar Födisch. After Födisch lost his life in another machine on 7 October, this particular aircraft became 7. Staffel’s ‘Blue 15’

Oblivious to this high-level planning, the three Sturmgruppen were content simply to enjoy their three weeks’ respite. After an abortive attempt by IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 to intercept an incursion by Fifteenth Air Force ‘heavies’ against targets in Austria and Czechoslovakia on 16 October, during which 15. Staffel lost a pilot to P-51s, the latter half of the month remained closed in by predominantly bad weather.

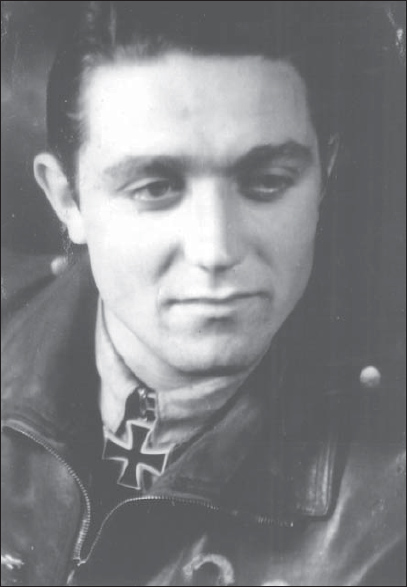

It was during this period that four Sturm pilots – two each from IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 and II.(Sturm)/JG 300 – were awarded the Knight’s Cross. The first to be recognised, on 23 October, was 15.(Sturm)/JG 3’s Fahnenjunker-Feldwebel Willi Unger, whose total was currently standing at 20, all of them four-engined bombers.

On 29 October two awards were made, one going to Oberleutnant Werner Gerth, who had so often led the original Sturmstaffel 1 in combat before being appointed as Kapitän of 11. (the later 14.) (Sturm)/JG 3. His number of Sturm victories had by this time risen to 26. The day’s second recipient was Major Kurd Peters, an ex-reconnaissance pilot who had taken over command of II.(Sturm)/JG 300 late in July. With no known victories to his credit, it must be assumed that he received the decoration for his qualities of leadership.

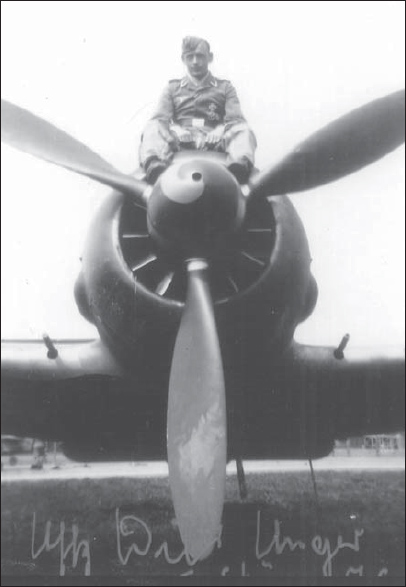

Knight’s Cross winner Fahnenjunker-Oberfeldwebel Willi Unger of IV./JG 3 sits atop his Fw 190. All but three of his final total of 23 victories were four-engined bombers (the remaining trio being Soviet Air Force machines claimed in February-March 1945)

The last of the quartet, honoured on 31 October, was Feldwebel Konrad Bauer. Joining II.(Sturm)/JG 300 in June 1944 after serving with JG 51 on the eastern front, where he had scored his first 18 kills, ‘Pitt’ Bauer had since increased his overall total to 34.

A fifth Knight’s Cross, awarded on 24 October, had gone to Hauptmann Horst Haase, the Kapitän of 2./JG 51 – the Staffel which had long been attached to IV.(Sturm)/JG 3, before being officially incorporated into the Gruppe as its new 16. Staffel on 10 August. Horst Haase had added ten Sturm kills to his previous eastern front tally of 46 prior to his transfer to the command of I./JG 3 on 3 October.

On 2 November the relatively tranquil existence of at least two of the Luftwaffe’s Sturmgruppen was shattered by the Eighth Air Force’s returning in force to strike yet again at the Reich’s oil-producing plants. Close on a thousand ‘heavies’ were despatched against synthetic-oil installations in central Germany, the main target being the huge Leuna complex outside Merseburg.

Oberfeldwebel Konrad ‘Pitt’ Bauer wears the Knight’s Cross awarded to him on 31 October. By war’s end, Oberleutnant Bauer was serving as Kapitän of 5.(Sturm)/JG 300 and, with a score of 68 (including 32 ‘heavies’), had been nominated for the Oak Leaves

This portrait of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s Feldwebel Klaus Neumann shows him as an archetypal Sturm Experte, sporting both the Knight’s Cross (won on 9 December) and the ‘Whites-of-the Eyes’ insignia. The last five of Neumann’s 37 victories (of which 19 were four-engined bombers) were achieved while flying the Me 262

Awarded a Knight’s Cross on 29 October 1944 following 26 Sturm victories with Sturmstaffel 1 and 11. and 14.(Sturm)/JG 3, Leutnant Werner Gerth claimed his 27th success on 2 November when he rammed a B-17 north of Bitterfeld. Although the ace managed to bale out successfully, his parachute failed to open and he fell to his death

Scrambling from Schafstädt shortly after 1130 hrs, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 first met up with the Bf 109s of I. and II./JG 3 before setting course almost due east towards the last reported position of the main bomber stream. They sighted the enemy some 30 minutes later to the northwest of Leipzig. While the Bf 109s fought desperately to keep the strong force of escorting P-51s off their backs, the Sturmböcke, led as usual by the now Major Wilhelm Moritz, bored in to the attack.

In the ensuing mayhem the Gruppe downed 21 Fortresses. One was claimed by the Gruppenkommandeur himself (his 44th victory), while no fewer than five of his pilots were credited with doubles. Among the latter was Sturmstaffel 1 veteran Feldwebel Willi Maximowitz, by now long recovered from his July injuries. Another was Feldwebel Klaus Neumann, ex-2./JG 51, whose brace of B-17s on this day took his score to 32, for which he would receive the Knight’s Cross on 9 December.

But, as so often in the past, success had come at a heavy price. IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 also lost exactly 21 of its own machines, with ten pilots being reported killed or missing, plus another five wounded. Among the dead was the Knight’s Cross holder of just four days, Oberleutnant Werner Gerth. The Kapitän of 14. Staffel had claimed his 27th, and final, victory by ramming. Whether this act was deliberate or not remains unknown, for although Werner Gerth managed to extricate himself from his damaged fighter before it went down north of Leipzig, his parachute failed to open.

II.(Sturm)/JG 4 had lifted off from Welzow some ten minutes after IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 had scrambled from Schafstädt. The Fw 190 pilots first rendezvoused with their escort (provided by the Bf 109s of JG 4’s other three Gruppen) before being vectored westwards towards Magdeburg. They encountered the enemy some 20 miles (32 km) to the southeast of the town, and were immediately pounced upon by hordes of vigilant Mustangs.

Once again it was the covering Bf 109s that bore the brunt of the enemy’s fury. This allowed several of IV. Gruppe’s Sturmböcke to get through to the Fortresses and claim at least four of their number. In return, IV.(Sturm)/JG 4 sustained eight combat casualties – five pilots killed or missing and three wounded. This represented over half of the unit’s attacking force.

The heavy Sturm losses of 2 November – which included two Staffelkapitäne – resulted in another relatively quiet three weeks as yet more replacement men and machines arrived to fill the gaps. Two new Staffelkapitäne were appointed, neither of whom would last long. Towards the end of this period a seventh serving member of the Sturm force was awarded the Knight’s Cross. This was the Kapitän of 5.(Sturm)/JG 300, Leutnant Klaus Bretschneider, who received the decoration on 18 November for an overall total of 31 victories (14 of them by night during JG 300’s earlier employment as a ‘Wilde Sau’ unit) culminating in his recent remarkable treble.

This photograph of Leutnant Klaus Bretschneider, Kapitän of 5.(Sturm)/JG 300, was taken upon the occasion of his winning the Knight’s Cross on 18 November. Less than a month later, on Christmas Eve 1944, he would be lost in action against USAAF Mustangs

Two of Bretschneider’s 5. Staffel pilots, Unteroffiziere Matthäus Erhardt (left) and Ernst Schröder, pose in front of the former’s ‘Red 8’, named Pimpf

On 19 November IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 and II.(Sturm)/JG 4 were ordered to vacate their bases in central Germany and transfer westwards, the former to Störmede, southeast of Osnabrück, and the latter to Babenhausen, down near Frankfurt. While II.(Sturm)/JG 300 remained at Löbnitz, deep within the Reich, the other two Sturmgruppens’ move had inevitably taken them much closer to the ground fighting on the western front. The reason for their transfer was soon made clear. Not only were they to continue their long-running campaign against the Eighth Air Force’s high-altitude bombers, they would also be expected to fly low-level missions in pursuit of the Allied fighter-bombers now marauding almost at will over much of western Germany.

Things did not get off to a good start. On 26 November, after days of heavy rain, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was instructed to scramble, no matter what, to attack enemy fighter-bombers reported over the Ruhr area. Despite the appalling conditions – visibility less than a kilometre (1750 yards) and the cloud base down to 75 metres (250 ft) – Major Moritz attempted to comply. But several of the heavy Sturmböcke, including the Kommandeur’s own, became firmly stuck in the boggy surface of the field while taxiing out. Take-off was clearly impossible.

At nearby Lippstadt the Bf 109s of I./JG 3 had managed to get off the ground, only to lose their recently appointed Gruppenkommandeur, Hauptmann Horst Haase, in a mid-air collision. The lead was taken over by Leutnant Walter Brandt, the highly experienced Staffelkapitän of 2./JG 3, but after finding no trace of the enemy, he broke off the mission and ordered a return to base. The foray had cost the Gruppe three pilots killed and five Messerschmitts lost – proof, if any were needed, of the atrocious weather in the region at the time.

Further members of 5.(Sturm)/JG 300 are seen in November 1944. They are, from left to right, Unteroffizier Schröder, Oberfeldwebel Winter, Oberfähnrich Piel, Oberleutnant Maier (a gunnery instructor), Leutnant Graziadei, Oberfähnrich Schneider and Fahnenjunker-Oberfeldwebel Löfgen. Of these seven pilots, only two (Schröder and Graziadei) would survive the last six months of the war

Veteran Sturm pilot Leutnant Siegfried Müller saw considerable action from mid-1943 until war’s end. Having initially been sent to II./JG 51 in Sardinia in mid 1943, he volunteered for service with Sturmstaffel 1 in March 1944. Subsequently flying with 16. and 13.(Sturm)/JG 3, Müller was posted to Me 262-equipped JG 7 in April 1945. A rare Sturm survivor, he had claimed 17 kills by war’s end.

Nevertheless, after landing back at Lippstadt, Leutnant Brandt found himself facing a court martial for failing to carry out orders. Major Moritz was threatened with the same, but saner minds then prevailed. He was, however, warned to expect a posting to a training unit in the very near future.

The next day (27 November) IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 went up against its old adversaries of the Eighth Air Force, which was out in significant numbers attacking transportation targets. Led on this occasion by Leutnant Siegfried Müller, the Gruppe was unable to break through the strong screen of escorting fighters. The Fw 190 pilots were fortunate to get back to Störmede without serious loss.

Further to the east, II.(Sturm)/JG 300 was not so fortunate. Its pilots, who were also part of a large Gefechtsverband led by Oberstleutnant Walther Dahl, were set upon by the now seemingly ever-present Mustangs. In a series of wide-ranging dogfights over the Halberstadt-Quedlinburg area – the scene of so many Sturm assaults in the past – the Gruppe lost seven pilots killed and four wounded. 5. Staffel’s Unteroffizier Ernst Schröder was very nearly one of them. With a damaged rudder, and unable to turn, he was attempting to escape at low level when;

There are many photos of Unteroffizier Schröder’s Kölle alaaf!, but few show ‘Red 19’s’ starboard side, which bore the name of his girlfriend Edelgard. This picture was taken on 25 November, just 48 hours before ‘Red 19’ was written-off . . .

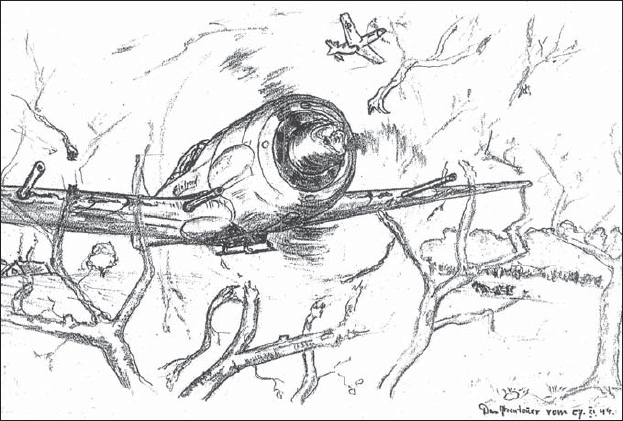

. . . and this is Ernst Schröder’s own sketch of the incident which hastened its demise as, harried by a Mustang, he unintentionally ploughs through the top of a large tree!

‘Suddenly a bare metal P-51, looking brand new, appeared just above to my left. I could clearly see the pilot peering down at me from his large glass canopy. He obviously didn’t want to overshoot and get ahead of me, so using his excess of speed he pulled up and away to port.

‘I could no longer see him but, expecting him to attack at any second, I nearly dislocated my neck trying to look behind me. When I glanced forward again, the edge of a forest of large trees was filling my windscreen. I heaved back on the stick, but there was an almighty crash as my “Bock” tore through the top branches of a huge tree at something over 500 km/h (310 mph). My cockpit immediately filled with blue smoke as I carefully tried to gain enough height to bale out.’

In fact, Unteroffizier Schröder managed to belly-land his machine on a nearby airfield. It was a sorry sight. The spinner and wing leading-edges looked as if they had been ‘attacked with an axe’, there were at least 25 bullet holes in the wings and fuselage, and lumps of tree were found embedded in the radiator. It was the end of the road for Schröder’s well-known ‘Red 19’ Kölle alaaf!.

The Luftwaffe lost over 50 fighters that day. They had not brought down a single heavy bomber!

The following day (28 November), IV.(Sturm)/JG 3, back hunting fighter-bombers at low level, managed to claim a brace of Mustangs near Aachen. And 72 hours after that a single P-51 provided the first victory for Hauptmann Hubert-York Weydenhammer, the Staffelkapitän of 15.(Sturm)/JG 3.

Then came 2 December.

That day’s targets for the Eighth’s ‘heavies’ were marshalling yards along a 37-mile (60 km) stretch of the Rhine between Koblenz and Bingen. Scrambled from Störmede shortly before midday, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was vectored almost due south towards the B-24s of the 2nd Bomb Division, heading for Bingen. The Fw 190 pilots intercepted the formation of 130+ Liberators, escorted by an even larger number of P-51s, while it was still on its approach west of the Rhine.

IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s own fighter cover (the Bf 109s of I. and III./JG 3) suffered a severe mauling in opening up a path through to the bombers, but their sacrifice (over a dozen pilots killed, others wounded, and 16 machines lost) paved the way for the last major Sturm assault of the war.

The Sturmböcke hit the B-24s over the rolling countryside between the Moselle and Rhine rivers to the southwest of Koblenz. In less than ten minutes they claimed 22 Liberators. This was exactly double the Eighth Air Force’s admitted losses but, again, the inexperience of many of the Gruppe’s young replacements pilots may partly explain this over-claiming in the heat of battle – no fewer than 13 of the credited kills were firsts.

For two of the claimants, their first victories were also to be their last. After attacking the bombers, it was the Focke-Wulfs’ turn to run the gauntlet of US fighters – and not just those of the B-24s’ immediate escort, but also the many others flying general sweeps of the Rhineland area now hastening to the scene of the action. Ten Fw 190s were shot down or written-off in crash landings, and at least four more were damaged. Five pilots were killed and two wounded.

Some of IV.(Sturm)/JG 3’s machines retained their ‘blinkers’ right up until the end of the Gruppe’s Sturm career, as evidenced by Unteroffizier Oskar Bösch’s ‘Black 14’, pictured at Schafstädt in the late autumn of 1944

This engagement effectively marked the demise of Major Hans-Günter von Kornatzki’s Sturm idea. Three days later, as if to underline the fact, Major Wilhelm Moritz relinquished command of the Luftwaffe’s original Sturmgruppe. He would see out most of the remainder of the war at the head of a training unit. The official reason for his departure was given as ‘combat exhaustion’, and this may not have been far off the mark.

IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 was not only the Luftwaffe’s first Sturmgruppe, it was also by far the most successful, and Wilhelm Moritz had been at its head throughout. Many of the surviving pilots who served under him still remember the quiet but authoritative ‘Pauke, Pauke!’ (‘Attack, Attack!’) call in their headphones as he led them into yet another assault on the seemingly endless streams of US heavy bombers.

Since its return from the misguided venture into France at the time of the Normandy invasion, IV.(Sturm)/JG 3 had been credited with the destruction of some 270 of those four-engined enemy bombers. But its successes had cost the unit well over half that number of Fw 190s, together with 76 pilots killed or missing and a further 44 wounded or injured.

The beginning of December also spelled the end of the road for II.(Sturm)/JG 4 as a dedicated bomber-killer Gruppe. According to one pilot, as soon as the unit received the order to transfer to Babenhausen for western front operations, the mechanics immediately started to remove the Sturmböckes’ heavy armour-plating and outboard 30 mm wing cannon to convert them into ‘light’ fighters.

Although, according to pilots’ log-books, the appellation ‘Sturm’ would remain in use right up until the final surrender, it was only II.(Sturm)/JG 300 – from its base at Löbnitz, in central Germany, about 75 miles (120 km) to the south-southwest of Berlin – which would continue to operate primarily in the anti-bomber role. And even it rarely, if ever, flew the true, massed Sturm-type assaults to which the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces had been subjected during the five months from July to December 1944. The opposition was simply too overwhelming.

Here is ‘Black 14’ again – note the broad wooden propeller blades – shortly before the Gruppe’s move to Störmede on 19 November. This photograph reflects even more starkly the almost unimaginable odds facing the Luftwaffe’s young fighter pilots during the final six months of the war. Of the 13 pictured here, ten would be reported killed or missing, one would be wounded, and just two – including Oskar Bösch (second right) – would come through unscathed