EDWARD KENNEDY ELLINGTON

“Uncle Eddie”

| Act I— | Juan-les-Pins, France: The 1966 Jazz Festival. I am “adopted” by Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn. |

| Act II— | Milano, Italy: Entrance of Herbert von Karajan in Ellington’s dressing room. |

| Act III— | Star-Crossed Lovers: After the passing away of both Strayhorn and Hodges I honor their memory by recording “Star-Crossed Lovers” with the Tommy Flanagan Trio. |

| Act IV— | Christmas in New York 1967/68: New Year at the Ellington mansion on Riverside Drive. Giancarlo Menotti asks to be put in touch with Ellington. |

| Act V— | Newport 1968: Ellington gives me a taped “interview-conversation” explaining the history of his Sacred Concerts. He also sings to me in Anglo-Italian. |

| Act VI— | What is Jazz? New York 1968: Ellington accepts to write an article on jazz for Italian publishers Fratelli Fabbri Editori. His outlook on jazz is fascinating. |

| Act VII— | Evelyn Ellington: Ellington introduces me to Evelyn, first wife of Mercer Ellington, and a warm friendship results. When my young son and I visit New York, we join Ellington in the basement recording studio of the Edison Hotel, where Ellington seats my son next to him on the piano bench to “assist him.” |

| Act VIII— | The Vatican: In the early 1970s RAI, the Italian National Radio, asks me if Ellington would perform a Sacred Concert in the Vatican for the Holy Father. |

| Act IX— | Final Interview: The Italian Television asks me to tape a very special interview with Ellington. He talks freely about his whole life story. That is our last meeting. |

| Act X— | “Fare thee well!” On May 24, 1974, he says goodbye. |

ACT I—JUAN-LES-PINS, FRANCE

The most precious and amazing memory I treasure—of the many historical artists I had the privilege of meeting—is the unique world of Edward Kennedy Ellington.

From early childhood, during the Second World War years, I had been a constant radio listener, especially to the American Forces Network, enjoying artists called Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Benny Goodman, Bing Crosby, Glenn Miller, Dinah Shore, the Dorsey Brothers, not to forget Dame Vera Lynn…and, way above them, was the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

Through the many years that followed I had learned the names of the soloists who gave us that special Ellington sound. Although I admired them all, Johnny Hodges was my favorite. Especially when the famous Ellington repertoire offered the heartbreaking ballad from the Romeo and Juliet suite “Such Sweet Thunder” called “Star-Crossed Lovers,” performed by Hodges with that sensuous, almost physically caressing voice of his alto saxophone. From the late 1950s, that ballad had become the showcase of his magic.

As my singing career progressed, I found myself performing at various International Festivals in Europe. One of the most prestigious being the Antibes–Juan-les-Pins festival, on the French Riviera, I was thrilled to appear there especially, as their greatest guest star was Duke Ellington, whose orchestra would also accompany Ella Fitzgerald, with Jimmy Jones at the piano.

On Tuesday, July 26, 1966, backstage at the Pinède Gould, I noticed Johnny Hodges standing by the stage steps. On an impulse I approached him: “Mr. Hodges, my name is Lilian Terry. I'm a singer. But above all I'm a passionate fan of your rendition of ‘Star-Crossed Lovers.’ I have attended most of your concerts in Italy these past fifteen years, always looking forward to hearing you play it. Recently, though, it's no longer in your repertoire, to my great disappointment. Is there any chance that you could play it tonight?”

Listening in silence, while inspecting me from head to toe, he shook his head: “Nope, sorry, we haven't played it in years. We've got a whole new book tonight, but…”

He hesitated, and then made up his mind. “Come on, let's go ask him…”

He guided me backstage to the beach cabins used as dressing rooms during the festival. He knocked, opened the door and, thrusting me in, he growled: “She wants me to play ‘Star-Crossed Lovers.’ Before you say no, take a look at her.” Then he stepped back by the door.

To my amazement I recognized “the great Ellington” stretched on a beach deckchair, wearing a short blue bathrobe, bare legs resting on a pillow on a chair in front of him. On his head was a hairdresser net to keep his locks in place. His eyes were closed and I just stood there, speechless. He turned his head and gave a close scrutiny to my whole appearance, from my short haircut to the white and gold sandals. His gaze rested on them as he pointed and asked: “Italy?”

“Yes, Positano.” I whispered.

Always looking at them, he answered Hodges:

“‘Star-Crossed Lovers,’ huh? Well, if you want to play it for her, go talk to Norman, and tell him it's OK with me.”

And, closing his eyes, he resumed his meditation, dismissing us.

So Hodges went looking for Norman Granz, dragging me along. He explained the subject. Granz looked at me, raising his accented eyebrows: “Well, if Edward agrees…” he shrugged and walked away from us.

For the first time, Hodges gave me a large, satisfied grin and patted my shoulder: “Well, we're on, kid. I'll play it just for you tonight. What did you say your name was?”

“Lilian. And thank you so much!”

“My pleasure. I'll go tell Ellington, he'll want to tell the guys…” then a bigger grin as he added “…but then again he might not…. See you later.”

When they began preparing the open-air stage for the orchestra's performance, I joined my friends of the French TV crew. As I perched beside them on the railing in the open wings, I informed them that there might be a surprise that night.

The band walked onstage among enthusiastic shouts of welcome and applause from the public: There was Sam Woodyard fiddling with his drum set, joined by bassist John Lamb. Followed the four trumpets of Herbie Jones, Cootie Williams, Cat Anderson, and Mercer Ellington. The middle row featured the trombones of Lawrence Brown, Buster Cooper, and Chuck Connors. Finally, the reeds with Jimmy Hamilton, Harry Carney, Russell Procope, Paul Gonsalves, and last…Johnny Hodges reached his chair nonchalantly. As he turned around to sit down, he noticed me in the wings and gave me a curt nod, then proceeded to ignore me throughout the concert.

It was now practically over. The last performance had been a very long exploit by my favorite soloist, and Ellington kept shouting his name repeatedly, “Johnny Hodges!” while the audience sent wave after wave of enthusiastic applause. Hodges, standing in front of the orchestra, turned to Ellington and then motioned with his head toward me.

With an amused smile Ellington went to the microphone, announcing formally: “Thank you very much for Johnny Hodges. We do have another request. A lady has come all the way from Rome and she's asked for a couple of numbers from our Shakespearean Suite “Such Sweet Thunder.” We'd like to do the title number for you now…oh no, Johnny Hodges is here, so let's do the other one, let's do the one which is Romeo and Juliet. And the Bard called them the ‘star-crossed lovers’!”

Walking back to the piano Ellington gave me a long look, satisfied with my obvious emotion; then, motioning with his arm toward Hodges, he announced in his famous hyperbolic style: “Johnny Hodges! ‘Star-Crossed Lovers’! Johnny Hodges!”

The whole band was searching for the music through their chart sheets—obviously unprepared for this surprise—while Hodges attached his instrument to his neck ribbon, stood by the central microphone, and practically turned his side to the public in order to face me in the wings. Ellington began the introductory arpeggios while nodding imperiously at his musicians, who began playing by memory. With evident emotion, I received the compliments of my French TV colleagues and settled to listen to the greatest gift Ellington and Hodges could have given anyone.

At the end of the concert I waited at the foot of the stage steps for Ellington to descend so as to thank him properly.

“My God! What an experience, Maestro Ellington! I shall never forget your kindness! But how did you know that I live in Rome?”

“My dear, I always find out who is the prettiest girl in town, especially if she becomes a member of my family. You are joining us for a ‘coupe de champagne,’ aren't you?”

As he spoke he slipped his arm through mine and led me firmly to where the rest of his “family” awaited him: his son Mercer, his nephew Stevie James, his hairdresser/valet Ronnie Smith, his musical assistant Herbie Jones, then a couple of old friends from London, Renée and Leslie Diamond…and on he went with the introductions till there were about a dozen people around us. I was presented as “Lilian, my Roman niece from Egypt” and obviously scrutinized by all of them. Which fact amused Ellington no end, as we entered the Provencal Hotel and went up to his suite.

When Billy Strayhorn joined the reception, Ellington led me to him: “This is our Lil from Rome, who loves ‘Star-Crossed Lovers’ madly.”

I noticed the white bandage around Billy's throat and recalled hearing about his serious health problems, possibly terminal. However, he was smiling cheerfully at me, offering his hand, so I introduced myself properly and expressed my admiration for all of his ballads, which I sang with great pleasure, especially “Lush Life.”

“Now that's really sweet of you, come and sit down. So you're a singer?”

He was extremely kind as he sat me next to him and we spoke of his music. Of course I confirmed my passion for “Star-Crossed Lovers.”

He smiled: “Ah, I see now why Edward decided to play it, just out of the blue. The guys in the band had a little problem, having to play it by memory, hah, hah…. However, I'm glad you asked for it; it's one of my favorites too.”

“I'm only sorry that it has no lyrics, I would love to sing it. And I would try to have that special sensuous ‘Hodges sound.’ Heavens, when he blows those long, languid notes…it's an actual caress!”

“Yes, it's very…physical, isn't it? And you would like to sing it?”

I nodded, and he patted my hand.

“Tell you what I'll do. Write me down your home address…you live in Rome, don't you? OK, I promise I'll send you some lyrics as soon as I get back to New York.”

I thanked him, though telling myself not to hope too much. I then expressed my admiration for another extraordinary composition of his, the suite “A Drum Is a Woman,” which I had often presented on my Italian radio programs.

“Really? I didn't know it was popular in Italy…”

“And I also sang one of the tunes, ‘You Better Know It,’ during a concert with the Kurt Edelhagen Orchestra in Cologne. They didn't know the suite, but they got the music from the States and Dusko Gojkovic wrote the arrangement for voice and orchestra.”

“Why then, you really are a member of the family!”

During the days that followed, Billy and I had the opportunity to spend more time together. His kindness touched me deeply, and on the day he was leaving for Paris we hugged each other as he was entering the limousine: “You know, Lil, if I'd had a daughter, she would probably have been like you. Take good care of yourself now, and I'll be sure to send you those lyrics. Bye…”

Going back to that first evening, at the reception, when I rose wishing everybody a good night, Ellington walked me out of the suite to the elevators.

“Ah, Maestro! What an unforgettable evening. You know, as a rule, when great and famous artists, such as yourself, are approached privately, they are often a dreadful disappointment. But with you…the essential human being is even more fascinating…”

With that special cool-amused smile of his he grabbed me by the shoulders: “Now that is the sort of phrase I adore. May I use it myself, on some other appropriate occasion?”

My sense of humor emerged through all the emotions experienced that night, and I promised very formally to put at his disposal my whole repertoire of the kind.

He looked closer and asked if I did not wish to “forget” my jacket and perhaps come back for it when the other guests had gone?

I looked him in the eye and shook my head. “No sir. Fortunately, my sense of preservation is stronger than my attraction for you. You would discard me tomorrow morning with your breakfast tray and without a backward glance. This way you might remember me at least till lunchtime.”

Still holding me at arm's length, he was grinning while scrutinizing me.

“Oh, I think I'll remember you long after that! As you wish, my dear. Tomorrow Norman has organized one of his fancy PRs. I am meeting Joan Miró at the Maeght Foundation, then there's the lunch at the Colombe d'Or at Saint Paul…the whole Granz production, so I won't be able to see you. But I want to see you the following morning. Stevie will come for you before midday, and we'll have breakfast here, at my suite. Remember, no food before then! Breakfast is a very important moment for the body!”

“Yes Sir! As you say, sir!”

“Now I'll give you four kisses for your four cheeks, and wish you goodnight.”

Two mornings later, at twenty to midday, Stevie James was banging on my door: “Hey, Lilian! We've got to move. Uncle Eddie said you were to wake him up at midday sharp. Hurry up!”

From that moment everything was rushed: washing, dressing, a brush through my hair, no time for makeup, hurry! Laughing and moving at a trot, Stevie and I discovered we had a similar sense of humor, and by the time we had entered Ellington's suite our friendship had been established.

“Wow, it's five to twelve. Wake him up Lilian, while I run his bath…”

There I was, alone in a darkened room with a naked jazz icon barely covered by a white sheet, snoring, face down in a huge bed. Why not? So what? Laughing silently to myself I sat by his side, laid both hands on the bed sheet and, starting with his lower back, began a massage moving up toward his neck and shoulders. At every move forward he would give a satisfied grunt as I asked a different question:

“…Who is the greatest American composer of all time?”

“…And who brings joy to millions of fans throughout the world?”

“…And who is admired and befriended universally, including by crowned heads of state?”

“…And who is an irresistible heartbreaker?”

By then I had reached his shoulders, so I paused as he turned his head toward me and sighed:

“Who?”

“Who else but you?”

Stevie called out that the bath was ready, and I moved rapidly to the living room.

Punctually, the room-service attendant rolled in the breakfast trolley as Ellington appeared—wearing his short blue bathrobe and hair net—to sit in his armchair, settling his bare feet on the usual raised pillow. Strayhorn entered the suite. He sat next to me on one side of the sofa while Stevie chose the other side. Seated opposite us, Ellington stared at my sandals and pointed accusingly: “That's a different pair from the other night. Always your Positano man?”

“Yes, he's a real magician, makes them in all shapes and sizes.”

“How many pairs do you have?”

“Well, I've been collecting them through many years, so…about fifteen?”

“Fifteen different shapes and colors? Hum…however, I like the white ones you wore the other night.”

“I'll be happy to have a pair made for you. It's quite simple: I'll draw the outline of your feet on a piece of paper and he'll create the sole exactly to your size, then he'll fit my white pattern on top of the soles and there you are.”

“We'll see. But let's not leave the water to cool now!”

Very formally he explained what his important breakfast ceremony entailed: To begin with, we were all to down two large glasses of hot water, one right after the other, to wash away the poison from our “insides.” At that point we were allowed the choice either of a continental breakfast with croissants, brioches, toast with bitter marmalade, or a tray of French cheeses, various breads, and a ham omelette. But he was adamant concerning the two large glasses of hot water to start with.

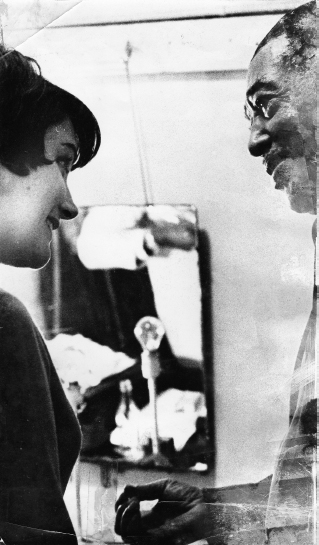

While still juggling with them, we were joined by trumpeter/assistant Herbie Jones carrying a large portfolio of paper music. He reminded Ellington that on that day they were to film “Duke Ellington at the Côte d'Azur,” organized by Norman Granz. He asked Ellington for instructions, but the Maestro was not in a mood for work; he replied that it all depended on the wishes of “la plus belle Lil.” Herbie asked: “Who?” and the three of them—Ellington, Strayhorn, and Stevie—pointed their fingers at me. Herbie lifted his faithful camera, always hanging from his neck, and while he asked them to hold the pose, he clicked one of my most precious pictures, as seen on the back cover of my record with Tommy Flanagan.

At that point the rhythm of the day was set for us by the Maestro, obviously in no hurry to comply with Granz's plans. He dressed and made his way downstairs, the four of us trailing as his retinue. The other guests of the Hotel Provencal, recognizing him, murmured their greetings with smiles of admiration as he made his way toward the main entrance. Suddenly, he stopped us in our tracks as he discovered the piano bar of the hotel, where the personnel were in the midst of cleaning up. He turned to me.

“Ah, a piano! Now you will sing for me!”

“Right now? I can't!”

Ignoring my protest Ellington walked into the room while the personnel faded into the background.

Stevie dragged me to the piano where his uncle, with an amused smile, began a musical introduction, saying simply: “You will sing this specially for me…with meaning!”

Fortunately, my spinning head recognized the melody and there I was, singing “Loverman” with Edward Kennedy Ellington at the piano and a group of surprised bystanders growing ever larger.

I sang the last phrase, “Loverman, oh, where can you be?” ready to make an escape, but Ellington rose and stopped me, smiling at the applause we had earned. He kissed my cheeks four times and we emerged from the hotel.

Once outside, he was recognized, and a wave of waiting fans came rushing up the steps clamoring for his autograph. He complied, while thanking them for their compliments, then he suddenly turned to me: “You see how very nice they are to me, just because I'm with a pretty girl like you?”

“Wow! That phrase is worth two of mine!”

“Now you're coming with me to my special underwear place. Underwear for me,” he specified, when he saw my alarmed look.

We went into a gentlemen's boutique where they had obviously been expecting him, for they had prepared a series of Eminence items. Ellington, amused, would ask for my advice, giving the impression that I must be very familiar with his underwear. I played along, advising him with obvious intimacy and then moved away to look at some handsome belts. I drew his attention to them.

“Look, isn't this belt rather elegant? It's slender and in this ‘English school tie’ silk, in blue and silver-grey. It would look very good with your ‘Ellington blue’ trousers, don't you think?”

He examined it; then, turning to the clerk, he asked for two of them, identical. He requested a pen and wrote something on the suede leather lining of one of them before handing it to me.

“Here, this way you'll remember me every time you wear it and I will do the same with mine.”

I read the message he had written: “A la plus belle Lil, wear this in good health. Love, Duke.”

“Good grief, you are really set on turning my head, aren't you? However, I promise not only to think of you each time I wear it, but that I shall keep it forever. [NB I still do to this day.] Thank you very much.”

Outside, with the crowd of fans surging around, Herbie reminded him of the filmed rehearsals that could no longer be postponed, and I took the opportunity to ask to be excused. He told me to be at his suite for dinner that evening, at eight sharp. We would then cross to the Pinède Gould in time for the orchestra's performance. He did not wait for my answer.

However, as one of my main activities was a weekly jazz program with the Italian radio network, my presence at Juan-les-Pins—apart from my singing appearance—entailed also various interviews with the artists attending the Jazz Festival. So with my faithful recorder I went to the appointments previously made and by late afternoon called the Ellington suite to excuse myself for not being able to join them for dinner. Stevie came to the phone: “Lilian? Uncle Eddie wants to know why!”

“It's his fault. In his overpowering presence I completely forgot that I am here as a working girl. I have a series of interviews to make and I promised Anita O'Day, who is using my rhythm section, to be there for the sound check and her performance this evening. So he must forgive me and I'll see him tomorrow, whenever he wishes.”

I could hear the long mumble of Stevie's explanation and a pause of silence. Then Ellington's sharp tone reached me over Stevie's voice: “Tomorrow morning! Before mid-day. Breakfast!”

I smiled, answering Stevie, “Yes, but on condition that I do NOT have to drink all that hot water!”

More mumbling and then Stevie's laughter as he talked to me. “You win! No hot water…but two large glasses of hot green tea instead. Good enough?”

“Good enough. Will you come for me tomorrow morning?”

“You bet!”

During those special festival days my whole life seemed to rise in a new direction. I struck friendships with well-known artists like Charles Lloyd as well as his young—then unknown—sidemen Keith Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette. Famous Jazz producer George Avakian, as charming as Ellington himself, accompanied them. Of course, during those days there grew a special friendship with Johnny Hodges, Paul Gonsalves, and Herbie Jones. In truth, through the years, I always received a friendly welcome from the Ellington band members, with knowing smiles in my direction as they played “Star-Crossed Lovers” whenever I attended their concerts.

At Juan-les-Pins a special friendship grew with Stevie James, who gradually told me about himself. He was the youngest son of Ellington's sister Ruth, who had married a handsome Englishman, which explained Stevie's striking looks with his honey-colored skin, blue eyes, and curly blond hair, and who was obviously spoiled by his uncle.

Once again it was almost midday and there I was, seated on Ellington's bed, pressing his back with both palms, working gently up to his neck. Once again I would ask him his “ego” questions while he appreciated the massage with soft grunts:

“Who is that most elegant orchestra conductor, so admired wherever he appears on stage?”

“And who is mostly dressed in royal blue trousers…the world famous Ellington blue…?”

“And who wears Ellington blue trousers that are a little bit too short for my taste?”

A movement under the white bed sheet proved he was reacting to my criticism.

“…On the other hand, who has the handsomest legs—which he shows off when he wears his short bathrobe—and who can therefore wear shorter trousers than usual?”

He was well awake now, as Stevie came in to announce that the bath was ready. I made a swift exit before Ellington could turn around.

So there we were, his faithful subjects: Strayhorn, Stevie, Herbie, Ronnie, Mercer…

While he poured out the glasses of hot green tea and Stevie distributed them, the conversation concentrated on that night's concert, the last one at Juan-les-Pins. With Mercer and Herbie they went through the program, which would include the two outstanding ex-Ellingtonian guests who would join the orchestra that evening: Ben Webster and Ray Nance. At the choice of the last song, Herbie grinned at me while asking Ellington: “Always ‘Star-Crossed Lovers’?”

“Every time we have ‘la plus belle Lil’ with us.”

Having dispatched the operation “last concert,” he turned his attention on me. “Now this is your third pair of Positano sandals…You'll have to take me to this man of yours. I want a pair just like the ones on that first night. White and gold.”

“By all means. To begin with, you will now stand on these two pieces of paper while I draw the outline of your feet. And you'll have the sandals when next we meet…”

He complied with curiosity, standing still while I marked the outline of both feet, then he asked, pointing at the papers, “He'll make a pair of sandals just from that?”

“He will. My friend Costanzo Avitabile is a magician and I promise you they'll be perfect.”

“Ah! Very good. And I'll pay for them.”

“Absolutely not! They would be my way of saying thank you for ‘Star-Crossed Lovers.’”

At that point Stevie explained that Ellington was very superstitious and believed that if a gift of shoes was made between two persons, then the shoes would walk away from the donor, causing a definite separation. Therefore, Ellington wanted to pay for the sandals. The argument was closed when we finally agreed—after much haggling where Ellington began by offering at least one hundred dollars—on the sum of one dollar.

The next day, when Ellington and the orchestra were leaving for Paris, he asked me to ride along in his limousine, with Stevie. Driving to the Nice airport we enjoyed the beautiful coastline on a perfect sunny day and somehow ended talking about poetry, discovering our mutual taste for it. He mentioned having studied Shakespeare while composing the music for the Stratford, Ontario, musical festival and quoted a piece of poetry from The Merchant of Venice:

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils.

Came my turn to offer a poem and I chose my favorite:

The moving finger writes: and, having writ

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

“Ah, yes, good old Omar Khayyám.” He approved.

“Actually, we have a saying in Egypt regarding whatever happens to you. It's ‘Kullu Maktoob,’ meaning that it's all written down in your Destiny, just as my passion for ‘Star-Crossed Lovers’ had to lead me to you.” I teased him.

He then began inquiring about Egypt and gradually wanted to learn more about me, my family, my broken marriage, and my musical career. I was amused at the serious way he listened to my answers to his very specific questions, such as the cost of raising a six-year-old son. I asked him if he was an Internal Revenue investigator, but I was touched to note that his flirting attitude held now a certain paternal kindness. He was particularly pleased to learn that my son had been born on the 13th of September. Wonderful! For that was indeed a very lucky number!

As we reached the Nice terminal, Stevie informed his uncle that he was driving back with me to remain in Juan-les-Pins to the end of the festival. Ellington gave both of us a piercing look.

“I see…Well, I want you to do your utmost to entertain our Lil as lavishly as I would have done. Here.” And he passed a large wad of money to his grinning nephew.

Came the moment to say “au revoir” and, while I expected a hug, Ellington extended his arm, offering his hand which I took, nonplussed, only to discover that he was trying to hand a huge wad of dollars to me as well. I recoiled, closing his hand over the money.

“What on earth are you doing?”

He was embarrassed: “I want you to have it…just like the rest of the family. I'm sure you'd make better use of it than they do. Please take it…”

“I can't, honestly. But I am very touched, and I promise that if I ever need help…it's you I'll turn to. Cross my heart.”

He shook his head, putting away the money.

They were calling him to board the plane. He gave me his “total embrace” and murmured, “Fare thee well!”

I completed the famous phrase: “And if for ever, still for ever, fare thee well.”

“No, not for ever, Lil…I'll see to that!”

A month later, back in Rome, I received a large envelope from New York with the music sheet and lyrics for “Star-Crossed Lovers” enclosing a little note of friendship from Billy Strayhorn. When I phoned to thank him he said he had done it willingly—wasn't I his adopted daughter? He was looking forward to hearing me sing it.

Once again, I relived the Juan-les-Pins extraordinary adventure that had brought me into the fascinating Ellington “family.” It was unbelievable and most extraordinary. What had prompted their adoption of one more anonymous admirer? Would they really remember me by next year?

ACT II—MILANO, ITALY

Six months later, in early January, I received a large envelope from New York and extracted a very large piece of paper, folded in four, which proved to be Ellington's special Christmas card, bearing his short poem of good wishes. So I was still a member of his “family” circle, although I wondered at the lateness of his Christmas wishes. I learned that he always sent them at a later date so that his wishes would not be “mixed up with the rest” of the season's greetings. I noticed a small message attached, handwritten. It said very briefly that they would be in Milano on Saturday, January 14, and I would be receiving an air ticket to join him at their hotel. If it was an invitation of sorts, it obviously accepted no refusal. I checked, and in fact the Ellington Orchestra was to appear at the Teatro Lirico on Sunday, January 15, 1967.

So on Saturday, January 14, I was dutifully carrying a brand-new pair of sandals for the maestro, created in my presence by Costanzo in Positano. Entering the hotel, I ran into Johnny Hodges and Paul Gonsalves. We made a big fuss of each other and I promised to accompany them for some special shopping for their ladies. Ella Fitzgerald smiled by and waved at me, saying, “No red roses, please!” remembering our first meeting, a year earlier, at the Rome airport of Ciampino, when I had offered her a bouquet of red roses with thorns piercing us both as we embraced. Herbie Jones came by and told me he had special pictures to give me from the Juan-les-Pins days. Harry Carney and other members of the band waved by, Cat Anderson calling out: “There we go again…star-crossed lovers, I bet!”

Among a group of men I recognized Arrigo Polillo, our leading Italian jazz critic, standing in friendly discussion with Ellington, who had his back to me as I approached. When Polillo spied me and began saying “Maestro, I would like you to meet…,” the Maestro turned around and, before Polillo could finish his phrase, had grabbed me without a word, planting his “four kisses” on my cheeks.

I had to burst out laughing, on the one hand for a most theatrical greeting but, above all, for the look of total amazement on the faces of my Italian friends, who obviously wondered at an unsuspected passionate affair between the Duke and their own Lilian Terry.

He looked at their bewildered faces and explained, very seriously: “This is ‘la plus belle Lil’; she's my niece, from Cairo.”

No other explanation given. He motioned to Ronnie Smith and asked him to show me to my room, saying he would call me as soon as the interview was over.

So there we were later, in his suite, reunited once more with Mercer, Herbie, Ronnie, the singer Tony Watkins, but sadly without Billy Strayhorn or Stevie James.

I handed Ellington the package, which he opened very carefully. He was a little boy examining a new toy. Yes, they were the true replicas of the white and gold sandals I had worn on the first evening we had met. And yes, they had been created on the shape of his feet drawn out on paper. He tried gingerly one of them but quickly removed it: “No. Before I can try them on, I must give you some money.”

“OK, you owe me one dollar. But do you like them, at least?”

He was still concentrating on his superstitious thoughts as he pushed the sandals back into my hands saying he could not keep them—not before his money had passed into my own hands. I could only take the sandals back, according to his wishes.

That evening we were all bundled in a large bus and driven out of Milano to a recording studio where the orchestra rehearsed some new items Ellington intended to perform the next evening. I discovered him to be rather cool and uncompromising as he worked his musicians until he had obtained the exact results he desired.

Typical of him, he decided he had to have the sandals at three in the morning, when we had all retired to bed. There was a discreet knock at my door and Ronnie's voice calling me softly. He apologized profusely, but Ellington had decided he couldn't wait to get his sandals, so here was some money and would I please hand them over? I did so, and Ronnie pressed into my hand the usual Ellington wad of dollars, which I tried to hand back to Ronnie, who shook his head, distressed. No, he could not take the money back, and Ellington wanted the sandals NOW! So PLEASE no problems at that very moment; I could always give the money back tomorrow.

“Very well, Ronnie, here you are. Hope they fit well.”

The next day I led Gonsalves and Hodges rapidly through the meanders of fashionable Milano, and then we rushed back to the hotel, as they had two performances that day and the bus would soon be there to drive the orchestra to the afternoon concert.

Ellington complained about my desertion in favor of “a star-crossed lover” as we were driven to the theater in a limousine. However, he also expressed his pleasure for the sandals, which reminded me that I had a wad of dollars to return to him.

He finally accepted the money back, minus one dollar, but very reluctantly and adding that it was the first time he had ever been handed any money by a lady!

We occupied his dressing room, where I helped him set the usual cushion for his tender feet on a chair in front of his armchair. We sat and talked of friends and family; he asked about my “lucky number” son and my singing career, then he gave me news of Stevie and his mother Ruth. He informed me that on his next tour I would be meeting his daughter-in-law Evelyn, who was sure to become a good friend of mine, as we had many points in common. When I asked after Strayhorn, I was very sad to hear that he was again in hospital, his terminal illness advancing rapidly. I mentioned the letter and lyrics to “Star-Crossed Lovers” that he had sent me, adding that one day I hoped to sing it in memory of him.

Then it was time for the afternoon concert to take place, and the Teatro Lirico was already packed. Shoes on, coat jacket hanging perfectly, Ellington-blue trousers a little short…he stepped out of the dressing room and was greeted by fans and friends as we went on backstage. As usual, the musicians filed in nonchalantly, and when they were all set in their place and Ellington was about to enter the stage, we realized that Paul Gonsalves was missing. No one had noticed his absence until then. The performance was about to begin, and I admired Ellington's cool reaction as—just before he stepped out in front of his public—he turned to ask me to take the limousine back to the hotel and drag that man from his bed and onto the stage. Please.

At the hotel I phoned Paul's room, and some minutes later his dreamy voice answered my urgent plea to wake up, get dressed, grab his horn, and come downstairs quickly, for the concert had already started. Hurry, please!

“Hey, Lil…. What? OK, OK…I'll be right there in a few minutes. Love you madly.” But his few minutes were endless, and by the time we did reach the theater, the orchestra was playing its fourth number. Paul grabbed his tenor and—smiling mildly at Duke and at his fellow musicians—he joined in the playing while walking in and sitting down.

When the concert was over, Ellington thanked me; I replied that he was very welcome as long as he remembered to play “Star-Crossed Lovers” that night.

While we relaxed in his dressing room before the second performance, he settled himself comfortably, resting his feet on the usual pillow. He was in a mood for chatting, expressing his thoughts and trying out on me what would be included in his future book. I sat at a small table with notebook and pen, and whenever he would say something funny, or special, I would write it down with the pledge to give him a copy for his personal use. Here are some of his favorite expressions, considerations, and advice: “Repeated listening makes for enjoyment of music. Jazz needs also understanding and an intelligent appreciation, although what counts is the emotional effect on the listener.”

“Good luck is being at the right place, doing the right thing with the right people, at the right time. When those four things converge, then it is good luck.”

“Anyone who loves to make music knows that study is necessary. Music can be a lucrative pursuit, but it must not be the only reason for participating in it. Then money can be a distraction more than anything else. Music…you either love it or leave it; in fact, what has money got to do with music?”

“How do you know if you're playing the right thing? When it sounds good, then it is good!”

At one point we were back to quoting poetry when I asked him if he had ever written any himself. To my surprise he seemed almost bashful, hesitant, and then admitted that he had written a poem, and Billy had created the music for it. I begged him to recite it to me as I scribbled the words:

Love came as a dulcet tone,

Humming up above, suspended.

To one who had been so much alone

It said “your doldrums blues are ended.”

Petals of red roses rare

Strewn along the path to guide me

The breath of spring had filled the air

Love of my life was there beside me…

At that very moment there was a peremptory knock at the dressing room door and Ellington asked if I would please…?

I opened the door and there stood, in all his handsome charm…Herbert von Karajan!

I stared in admiration as he smiled at me, amused: “Good evening. I have come to present my homage to Maestro Ellington…”

“Good evening. By all means, do come in, sir!”

He entered as Ellington got up from his armchair, and there was a friendly greeting between “Herbert” and “Edward.”

I stepped quietly outside, on a cloud. One of the greatest classical directors had asked to “present his homage” to the greatest jazz director, and I had been a witness to it!

My only regret was that I was not given the rest of Ellington's poem to jot down.

The evening concert was excellent, with very wide-awake musicians who played long solos for an enthusiastic public. Ellington was enjoying himself, smiling at me from time to time as I stood in the wings, waiting for the moment when Hodges would play for me. Suddenly I realized they were actually playing the closing signature tune! I whispered to Ellington as he sat at the piano:

“If there's no ‘Star-Crossed Lovers,’ then I'll take my sandals back!”

He threw his head back, grinning, and nodded. The very moment the signature tune ended he went to the microphone and informed the public: “We have a request from Miss Lilian Terry, the greatest singer in Italy. She would like to hear the Romeo and Juliet theme from ‘Star-Crossed Lovers,’ the melody played by Johnny Hodges!”

Then he sat at the piano and began the introductory arpeggios.

Hodges got up with his alto sax and smiled at me, going to the microphone.

Once again, the orchestra performed my beloved ballad with my beloved soloist.

ACT III—STAR-CROSSED LOVERS

To my deep sadness, I was informed that Billy Strayhorn had passed away on May 31, 1967. His funeral would take place in Harlem on June 5.

Three years later came the sudden, unexpected passing away of Johnny Hodges. It happened on May 11, 1970, in the office of his dentist. The news was unbelievable, and I felt bereaved, remembering the way he would play “Star-Crossed Lovers” with that lazy smile, as if we shared a secret. First Swee'Pea and now Hodges. I drew out the lyrics to their magic ballad and promised myself that one day I would record it to honor them.

As always, Fate took things in hand at its own pace and in its unfathomable way.

It was twelve years later that, at the end of a Jazz Festival at the Rome Opera House, a group of us went to a late dinner and I was seated between Max Roach and Ran Blake. Opposite me sat Tommy Flanagan, whom I admired immensely, especially for his art in accompanying singers. He asked me about my activities, and I mentioned my work with RAI radio and TV, the annual concert season I was producing for the city of Bassano del Grappa…then Max spoke up: “Yes, but she's not telling you what a good singer she is!”

Tommy seemed curious. “Is that so? And which is your latest recording?”

“Oh, that was ages ago.”

“And why is that?”

“I decided years ago that I would not enter a recording studio again, unless it was with Tommy Flanagan. You are the only asset I truly envied Ella for.”

“I see…. And what kind of repertoire did you have in mind?”

“Ah, very special songs that have a personal meaning for me.”

“Such as?”

“Well, I recall singing ‘Loverman’ at Juan-les-Pins one afternoon in 1966, accompanied by Duke Ellington at the piano.”

“Ellington?”

“Yes.”

“OK, ‘Loverman.’ Next?”

“Well, Ellington means Strayhorn, who means ‘Lush Life.’”

“Very good…next?”

“Ellington plus Strayhorn brings to mind Johnny Hodges and his sensuous way of playing a particular ballad that has never been sung before. I told Billy of my disappointment that it had no lyrics; he promised to send me a text, and a month later…there it was!”

Tommy was becoming very attentive.

“And what song was that?”

“It's from the suite ‘Such Sweet Thunder…’”

I leaned over the table toward him and he met me halfway to say in unison:

“Star-Crossed Lovers!”

He exclaimed, “I knew it! Why, do you know that's my very favorite ballad and hardly anybody plays it? And Swee'Pea gave you the words himself? OK. Let's do it. Now which recording date would you have in mind?”

He was drawing out his agenda and turning the pages. I looked at Max Roach, who nodded; this was really happening—Tommy Flanagan was willing to go into a recording studio with me. We exchanged addresses and phone numbers, and I said I would speak to my producer in Milano.

Of course, Giovanni Bonandrini was delighted to add such an LP to his “Soul Note” production list, which had already earned him the approval of the jazz press worldwide. We contacted Danish contrabassist Jesper Lundgaard and Ed Thigpen, “Mr. Magic Brushes,” who also lived in Denmark. Tommy approved, and we set a date.

So, on April 17, 1982, we were entering the Barigozzi Studio in Milano, where Bonandrini and Giancarlo Barigozzi, saxophone player and excellent recording technician, were waiting for us.

The first step was a “cappuccino and cookies” work meeting with Tommy and Diane Flanagan, Lundgaard, Thigpen, Bonandrini, and Barigozzi. Incidentally, that was the first of many snacks wherein we discovered that Tommy had a certain weakness for cookies. From that day, he was “the Cookie Monster.”

Each song was recorded and then approved by all of us together.

Tommy was in command of the trio with a touch that was masterful yet gentle. From his introduction to the first song “Loverman”—so logical and so thoughtful—we went on to the sophisticated “Lush Life,” then to the magic duet he and I enjoyed with “Star-Crossed Lovers.” Followed “Black Coffee” with a grateful bow to Peggy Lee; “I Remember Clifford” to thank Benny Golson, and naturally for Brownie. We then chose Mr. Monk's “’Round about Midnight,” closing inevitably with Lady Day by choosing “You've Changed.”

As we listened to the playback I was ever more aware of how, throughout the whole record, Tommy had enhanced my performance with his unique phrasing and what I called his “languorous touch.”

The brief Italian tour that followed was a continuation of the magical “together” feeling with the trio. When, upon saying goodbye, Tommy asked me what would be the title of the album, I replied on the spur of the moment: “Lilian Terry Meets Tommy Flanagan—A Dream Comes True.”

He gave me his “chinaman” smile of approval, a big hug, and off they all went.

Good friend George Avakian, pleasantly surprised that I had recorded after ten years of silence, and in such good company, wrote very flattering liner notes. The recording was an immediate success, especially in Japan but also in the United States.

The ballad that surprised—and therefore was most played on the air—was “Star-Crossed Lovers.” I had recorded it with a saddened heart, remembering Johnny Hodges and Billy Strayhorn, yet filled with gratitude that two such huge artists should have given me their friendship. Thanks to Tommy Flanagan, the dream of honoring them had really come true. Alas, today also Tommy Flanagan has gone, adding his shining star to the musical heavens.

ACT IV—CHRISTMAS IN NEW YORK 1967/68

I spent the 1967 Christmas holidays with my friend Jan Olson and her husband in a fascinating but freezing New York. Soon after Christmas Day I met with Stevie James for an elegant lunch where he introduced me to his girlfriend of the moment. He also gave me Ellington's personal phone number with firm instructions to call him the next day, at midday.

I complied, and we had a long chat where he informed me that they were rehearsing his Second Sacred Concert, to be performed on January 19 (1968) at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Ah, what a pity, I was due back in Rome before then! However, we made an appointment for “breakfast at twelve” the next day at his apartment on Riverside Drive.

Arriving punctually, I admired the exceptional view on Central Park from his elegant suite and met his sister Ruth, who, upon learning I lived in Europe, told me about her early studies in Paris. She then added how much her son Stevie had enjoyed visiting France with his uncle, the previous year, and especially his holiday in Juan-les-Pins. Stevie sat grinning while his amused uncle offered us some more green tea.

I was also invited to Ellington's New Year's Eve party, where I met a great number of interesting people from various milieus: theater, film and Broadway stars mainly, but also a good sprinkling of fashionable personalities. They were all very elegant and obviously successful. Ellington received them graciously, accepted their flattering compliments and seemed to be on rather intimate terms with all of them, especially the ladies. It was an extremely interesting experience, and I loved watching him move from group to group.

At midnight, everybody was kissing everybody else. When he came over to where I stood talking to Don George, Duke warned him to stop flirting with his niece. He then kissed me his Happy New Year wishes, and I pleased him with one of our exaggerated compliments: “Ah, have I told you how extremely handsome you look tonight? The whole room is full of beautiful people, but they really shine through your own reflection upon them.”

He motioned toward me, asking Don, “See what I mean? Could I ever let her go?”

“Yes; however, right now I really have to be going as I promised to drop in on another party. Could I call a cab…?”

But Don George insisted on accompanying me instead. As Ellington saw us to his door, he gave me the usual four kisses on the cheeks and his “total embrace.”

A few days later I received a phone call from Italy at Jan's home informing me that Maestro Gian Carlo Menotti was asking me for Ellington's private phone number, as he wished to speak to him directly about a possible performance at his “Festival dei Due Mondi” at Spoleto the next year. He had been told, in Italy, that I had a direct link to Ellington. Surprised, I explained that all I could do was give Ellington whatever phone number Maestro Menotti wished to be reached at, and they could take it from there. When Ellington took note of the message, he was amused: “Ah, Lil! You see? They all know about us.”

“So it would seem.”

“When are you flying back to Rome?”

“Tomorrow afternoon. But I'll be at the Newport Jazz Festival this summer—will you be there?”

“Yes, briefly. I'll write you a poem.”

“I'm sure you will…! Ciao bell'uomo! Success for your new Sacred Concert!”

Christmas poems

Ellington's pleasure in writing poetic messages emerged every Christmas in the shape of his huge paper, folded in four. Having managed to save four of them, through all these years, I'm happy to offer you their texts.

The first one read:

You've been such good girls and boys

Every day of the year

Let me tell you of the joys

You'll be very glad to hear

There's a day known as Christmas

December Twenty-Fifth

Santa Claus comes visiting

And that is not a myth

Santa Claus is good-natured

And likes a Christmas tree

He wears a handsome smile

And he's as stylish as can be

Santa's sleigh is packed, complete

Santa's in the driver's seat

Bringing every good boy and girl

Something nice and pretty and sweet

Signed: Duke Ellington

The next Christmas wishes were briefer but in a large classic Grecian setting:

The first spring blossoms in the tree

The soft, warm summer breeze

Expectant autumn on her knees

Winter and

A boy

Christmas Joy

Also signed Duke Ellington.

The third huge Christmas card had the poem zigzagging white on deep pink:

The echo of that

First Christmas day

Is still here and it's bright and gay

Ringing clear

And bringing cheer

Year after year

And it's here

To stay

Usual signature: Duke Ellington.

The last greeting in my possession is actually half the size of the former sheets and with a totally different personality as far as the poem and the picture, both being in a very modern style.

Life is—love is

Sweet is—right is

Beauty is endless life

And love—and light

And sweet—and beautiful

Endless Christmases

And Happy New Years

And Ash Wednesdays

And Joyous Easters

To come—to past

To future—to you

To yours—to ours

To us

Below the signature of Duke Ellington you can read, in a corner, a very tiny piece of information: Design by Stephen James.

ACT V—NEWPORT 1968

I spent four extraordinary days at George Wein's 1968 Jazz Festival at Newport, under the brotherly supervision of Max Roach and Papa Jo Jones. I was meeting and interviewing jazz icons such as Nina Simone, Ray Charles, Cannonball Adderley, when, finally, Ellington made an appearance on the fifth of July.

He told me he was leaving Newport soon after the orchestra's performance. However, he had time to chat with me and, as we relaxed in a quiet corner, he consented that I tape our talks.

I hoped to obtain some answers from him regarding his decision to turn to religion for his musical inspiration, as shown by his First Sacred Concert followed by his Second Sacred Concert, performed a few months earlier, on January 19 at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Hereunder you will find the essence of that long conversation with a very relaxed, reminiscing, amused, and amusing Ellington.

The first question was: “How did you happen to write sacred music and what are the feelings that you are trying to express through your sacred music?”

“I did my first sacred concert because I was invited to do a sacred concert at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco. They had heard some of the things I had done before, which were spiritual and gospel flavored…so they invited me to do a whole concert. Such an invitation as this, going into this beautiful cathedral…was quite a bit of a shock, and I said, “Wait just a minute. I have to get myself together and bolster up my eligibility, this that and the other, you know? So I got organized…and about a year later we did it! It was September 16, 1965. We took it on the road in America and Europe.”

“Where in Europe?”

“Coventry Cathedral and Great St. Mary's at Cambridge.”

“Then the Second Sacred Concert…”

“The Second Sacred concert was much bigger than the other one. It was over two hours long without an intermission; we employed the entire band, four choirs, and twenty-two dancers.”

“Now, what are the feelings that you are trying to express through the sacred music?”

“Well…first of all, when you get the invitation, you have to decide whether you're going to do it…or regret. Then you go back to when you used to go to church every Sunday…first to my mother's family church, then to my father's family church. One was a Methodist and the other a Baptist, so I went to two churches a day…then later, after I came out of school, I read the Bible completely through, about four times, and I found out in reading the Bible that I actually understood what I had learnt in school. It adjusts your perspective, your scale of appraisal in life and so forth and a very valuable contribution, cause there's nothing new…. So what we do in our concerts is to preach, with our music. We do fire and brimstone ‘sermonettes’ with titles like ‘Don't get down on your knees to pray until you have forgiven everybody…’ and the freedom things: ‘Freedom to be the contented prisoner of love,’ ‘Reach beyond your reach, to reach for a star,’ or ‘To go about the business of becoming what you already are.’

“Then we have the Billy Strayhorn freedoms of course, which were the serious things. Billy lived with these major freedoms: Freedom from hate unconditionally; freedom from self-pity; freedom from fear of possibly doing something that may help someone else more than it would him; and freedom from the kind of pride that would make him feel he is better than his brother.

“Then there's the thing about Heaven, like the phrase ‘Heaven to be is the ultimate degree to be,’ and these lines I tested with my theologian friends, you know? I got the greatest response; a reverend in Connecticut wanted to record that phrase to study it, and also other theology experts were consulted, then I recall Rabbi Shapiro who went back to the ancient Bible…. So you get associated with these people, you see? And we feel like we are a kind of messenger. We are talking to people…but we are not missionaries, of course.”

“Tell me, is this a field that you wish to really enter into and widen?”

“This is not ‘career’; I don't ‘work’ at this…. This is a thing where you make observations; these are arguments, like you present a case. You go to court and you present the good guys and you say, ‘These thousands of people have dedicated their life to it; after all, they're not suckers. Just because you've got a million dollars, so what? One day you're not going to have it.’ It's a great form of security for anybody who can understand it. I mean, understanding is one of the…I mean, wisdom is valueless without understanding (pause). Did I say something profound?” he asked, grinning.

“What will you do now, in the near future? Are you going to take a rest?”

“Rest? No! Rest! I never rest, I'm scared to rest!” he laughed, then went on.

“I'm writing a work for the Los Angeles Philharmonic which I'm supposed to do on the third of August”

“That's very good!”

“It's not very good because this is now the fifth of July!”

“Will you be using the Philharmonic Orchestra and your band?”

“No, just the orchestra”

“Just the orchestra and yourself on piano?”

“No, no piano”

“So you'll be composing for the Philharmonic and directing it?”

“Yes. You know, one of the greatest thrills I had with a Symphony Orchestra is when we did the ‘Symphonic Ellington’ album…did you hear it?”

“Yes! I have it!”

“Yeah, you know, we'd planned to record these four orchestras in Europe: the Hamburg symphony, the Stockholm symphony…”

“The Scala…”

“The Paris Opera Orchestra and then La Scala Orchestra. And when I get to Milano, of course, the orchestra has got a rehearsal that afternoon, and then they've got to go back and play ‘La Bohème’ that night. So, in other words, I can only have them for two hours, and you cannot do a rehearsal and record within two hours, so at ten o'clock in the morning I start writing a new number…and I do the thing called———”

I interrupted him, naming the number in unison with him:

“La Scala, she too pretty to be blue…”

He was pleasantly surprised: “Oh, you know it?”

“Of course I know it!”

“Say that in Italian,” he asked me.

“E’ troppo bella per essere malinconica.”

He listened, delighted, and approved in Italian:

“Molto bello, molto bello! Grazie mille!” he laughed.

This brought us to his promise that he would sing a special ditty of his own invention, in Italian, for me.

“And now, as a gift, I want you to sing your Italian song for our radio listeners, as you promised.”

“Well, you have to understand now: this is a song I first wrote in 1950, on my first visit to Italy. In Milano, Maestro Rizzo was sort of guiding me around and I was learning Italian. And naturally the first thing you learn to do is to count. And I was combining, you know…it was a real quick thing ’cause I was only there a little while. Did you ever know a gypsy violinist…Nino?”

“In Milano?”

“Yes, he used to play at a Piccolo…”

“He has a Hungarian restaurant?”

“No, not now, he died…”

“Oh, then no.”

“Oh, listen, I started to tell you about the La Scala Orchestra…when I heard those violins…I almost flipped! It was the greatest thing in the world! Absolutely!”

“Thank you, thank you very much.”

“Too much!”

“So, would you be happy to compose something for the La Scala Orchestra?”

“Oh, I'd love it! I mean, well…. You know, my imagination normally doesn't run in that direction and…but I mean it would be a gas…to do it.”

“All right, I'll see if there is anything I can do about that, but first…you must sing the song.”

“Which song is that?”

“The ‘Uno, due, tre’ song.”

“Uno, due, tre…sing it?!” he was alarmed.

“Sing it!” I confirmed.

“You're going to record it, eh?”

“Yes!”

Obviously amused, he surrendered and sang—to the various bystanders’ surprise—the following opus:

Uno, due, tre.

Quattro, cinque, sei.

Sette, otto, nove…

Won't you come over?

Nove, otto, sette, sei, cinque, quattro, tre

Do you know that you're the “uno per me?”

Such a bellissimo “due” are we

And we'll be “bella, bella, bella” when we're three!

Uno, due, tre, quattro, cinque…say you'll name the day

“per voi e per me” [pronounced “may”]

We laughed together as he accepted my very formal compliments.

“Thank you very much, Maestro. And when are you coming to Italy?”

“Well, I'm supposed to come after the first of the year, sometime.”

“After the first…in 1969? All right then, we'll say “arrivederci in Italia.”

“Arrivederci…how do you say ‘I love you madly’ in Italian?”

“Vi amo follemente!”

“Vi amo…follemente. Vi amo?”

“Yes, when it's general. For one person it's ‘ti amo.’ Vi amo is for everyone.”

He then repeated it to me in perfect and passionate Italian style, hand on his heart:

“Vi amo follemente!”

“Grazie! We hope so…”

“Prego!”

With his amused smile he had stood up as he was being called away, and then turned at the door to remind me that I would be receiving an air ticket at my home in Rome, to join him in Milano in October. We would celebrate his seventieth birthday.

He added: “You know what kind of birthday gift I'd love from you…don't you?”

With a wave of his hand and an amused-wicked grin he walked away.

ACT VI—WHAT IS JAZZ? NEW YORK 1968

I had just returned to New York City from the Newport 1968 Festival when I was requested to join Ellington at his house rather urgently.

He introduced me to a representative of the Italian publishers Fratelli Fabbri Editori; famous for their popular editions on most subjects, they had now decided to tackle the musical world. They had produced an excellent series regarding the various forms of music, presented with a booklet plus an EP recording. When they had come to the music called jazz, they had decided to obtain a long preface by the greatest jazz personality alive. “Il grande Ellington!”

As usual, Ellington was amused to present me as his niece, and he declared that he would write the preface on condition that I should be the translator into Italian. At his worried look I reassured the Italian gentleman that I had been an official Italian-French-English translator-interpreter at FAO of the UN, in Rome, for seven years. And no, I was not really Ellington's niece, but yes, I was that Lilian Terry with the RAI radio program on jazz music that was aired every week from Rome. Reassured, the gentleman accepted Ellington's conditions as well as the choice of the music that would be used for the EP: “Rockin’ in Rhythm,” “In a Sentimental Mood,” and the “Black and Tan Fantasy.” He left for Milano hoping to receive the papers at our “very earliest opportunity.”

I was due back in Rome myself, so Ellington agreed to prepare his papers and send them on to me. Knowing his reputation for procrastination till the very last minute, I gave him a definite time limit, which he noted down, protesting for my doubting his word.

The papers arrived, and I was fascinated by yet another facet of Duke Ellington's personality: very serious, scholarly, something of the sociologist, giving his precise judgement on jazz history as it spread worldwide. I translated the papers faithfully and forwarded them to Fratelli Fabbri in Milano, who proceeded to publish the booklet and EP recording, as agreed. It came out in 1969.

Being the property of the editors, I will not write down the original Ellington papers, but I can give you the general gist of it according to the various interviews I recorded with him through the years. These interviews were, as always, faithfully typed out and handed over to him for his own future use.

To begin with, his reaction to the word “jazz” itself was definitely and surprisingly negative. He would enounce, a shade snobbishly: “We stopped using the word ‘jazz’ in 1943.”

“And what is it called now?”

“The American idiom. Or else music of freedom of expression. Definitely not jazz.”

“Does the word ‘jazz’ have a racial connotation for you?”

“It's not a matter of color, but it does enclose our music within a ghetto, which causes various problems. But I would not say it's racial. The problem is rather economical.”

“Such as?”

“Well, when you enter the world of music, you must seek your rewards through living it, experiencing it. Now, music can also be lucrative, and of course you do have to make a living through your music. But it becomes a matter of how much money you are determined to make and on what terms. It can distract you from the reason why you chose to be a musician in the first place. I always say: ‘Music, love it or leave it’. Actually, what does money have to do with music?”

I considered the large amount of money his worldwide musical empire brought to him through his records, printed music, the annual world tours, and I decided to move on to another subject.

“Would you say that the roots of this American idiom music emerged spontaneously? Through the specially gifted artists who could not read a note of music, like Buddy Bolden or Armstrong and all the way to Errol Garner today…?”

“Quite true. I myself, after a few useless piano lessons in my childhood, began playing exclusively by ear. I even composed my first tune called the ‘Soda Fountain Rag’ during my high-school years. It was a big hit with the students, but I soon realized I needed to study music seriously.”

“So today you would advise young people interested in becoming jazz musicians to take music lessons?”

“Although for many years I prided myself for creating my music successfully with hardly any real classical music studies, today anyone who loves to play any kind of music discovers very soon that study is necessary. I would add it's essential.”

“What other advice would you give to a music student?”

“Another important aspect of their education is that they must also take time to listen to the music, carefully and repeatedly. That's what makes you really enjoy the music, whether you're a musician or a listener. The more you listen, the better you understand and appreciate intelligently the music.”

“And what should the musician aim at, when he performs?”

“Above all you're aiming at the emotional effect of your music on the public. You can always tell when that link has been established, and do you know how you can tell? Because you are playing a musical statement which you can feel is important not only to you but also to the listener. When it really sounds good…then you just know it is good. And the public's ovation confirms it.”

“There is a special, unique quality in the sound of your orchestra that makes it recognizable with eyes closed. What is your secret?”

“Well, first of all, you must know that the music that is written for my orchestra takes into consideration each of their outstanding qualities as musicians but also whatever limitation they might have. Of course, specific instrumentalists with their own musical personality get special compositions particularly suited to them, like your Hodges with ‘Star-Crossed Lovers.’ When he died I declared officially, ‘Because of this great loss the band will never sound the same again,’ and it has not.”

ACT VII—EVELYN ELLINGTON

From October 1969 I would accept invitations to join Ellington on his annual Italian concerts if and when I was free, which meant hopping from Rome to Milano, to Bologna and all the way down to Bari.

Sometimes, to my great amusement, Ellington would be in an unusual state of embarrassment in greeting me, and I would know he had been joined, unexpectedly, by his semi-official companion whom everyone referred to as “the contessa” and who was supposedly jealous enough to carry a gun in her purse. On those occasions I would reassure him, mock seriously, that I had accepted his invitation mainly to hear my good friend Hodges play his ballad for me and that I had no problem in keeping well away from him.

In Rome I finally met his daughter-in-law Evelyn Ellington, not to be confused with his other official companion Evie. Evelyn was an extraordinary woman who combined kindness and strength, along with a delightful sense of humor. As Ellington had foreseen, we were soon at ease with each other.

Evelyn was Mercer's wife and the mother of three handsome youths. I believe Mercedes was on her way to becoming an affirmed stage dancer; Gaye was a young lady who studied art; Edward—the tall elegant replica of his namesake grandfather—was studying to become a sound engineer.

Through the years, Evelyn and I kept in contact, and I could well understand Ellington's total trust in this straightforward lady, wholly dedicated to her family.

In 1971 my son Francesco was about to enter sixth grade and, as had been promised him, he was now to make his first grand tour of the United States.

Evelyn informed me that she would pick us up at the airport in New York and added that Ellington had booked a room for us at the Edison Hotel, where he was rehearsing a new album in the Edison Recording Studios. He wanted us within his reach.

My son was totally excited during the long plane trip, and finally there it was: the amazing view of the Big Apple from the skies. Then he passed through the airport gate and there was this lovely, elegant black lady who welcomed him to New York with an embrace.

“Francesco! There you are at last, welcome to the United States! I'm Evelyn, a friend of your mother's. We have a car waiting for you outside.”

She led us to a huge white limousine with chauffeur, and Francesco was completely bowled over. While he took in the bewildering magic that is New York, Evelyn explained that Ellington's orders were “that we should take possession, briefly, of our room to then join him, rapidly, at the Edison Studio in the basement of the hotel, where he would give us a proper welcome.”

Yes, sir!

We settled “briefly” in our room, made ourselves presentable, and then followed Evelyn “rapidly” down to the studio.

The orchestra was spread in a semi-circle around a grand piano where Ellington sat playing some notes and, from time to time, correcting the music displayed on the sheet in front of him. Raising his head, he saw us standing discreetly to the side. He rose from the piano and came directly to my son who was kissed soundly on the cheeks four times.

“So there you are, Francesco! Is it true you were born on September 13th? Now that is a very lucky number, did you know? I'll tell you a secret of mine that will help you all your life: Good luck comes to you when you're at the right place, doing the right thing with the right people and at the right time; always remember that and you'll be just fine.”

Francesco had been mesmerized from the first kiss on the cheek, listening intensely and nodding. Ellington went on: “I hear you are entering the Rome Conservatory this fall? You will study the piano?”

My son finally found his voice and replied shyly, “Yes, and also harmony.”

“Why, then we are compatible! Know what? I want you to come and sit next to me at the piano and to be my assistant while I resume working with the band. Will you do that for me? I'm sure your mother will allow you. Now come along, we have work to do.”

They sat side by side on the long piano bench, and Ellington handed Francesco a container with a dozen pencils and a sharpener, explaining, “You see, I need these pencils to correct my music and they have to be extremely sharp. So each time I shall use a pencil and then set it down, you will take it, sharpen it, and put it in this jar, ready for use.”

They nodded at each other. For the next magic half-hour Francesco was Duke Ellington's “special assistant.” That was the only time they were together. Yet the clear memory of every moment, and every word spoken, remained embedded forever with my musician son.

Obviously, my affection for Ellington was becoming deeper as he revealed more hidden aspects of his kindness, thoughtfulness, understanding, and patience with the persons he chose to allow into his privacy.

His behavior with me was familiar and relaxed; he often teased me with the amused, flirting attitude of the frustrated lover he would put on, while I told him that his attraction would only last as long as I would say “no thank you,” His embraces were always “total,” from shoulders to lower back, yet never disrespectful.

There was also the verbal game between us that we both enjoyed. One day, as we were parting with the usual embrace, he asked me suddenly: “You know what attracted me about you in the first place? It's that mixture of girl and boy in you; your short haircut with your frivolous sandals. You walk like a girl but move swiftly like a boy.”

“Girl and boy? Am I to take this as a compliment?”

He smiled, sphinxlike, as he let me go, obviously satisfied with my wondering reaction to his comment.

ACT VIII—THE VATICAN

In the early 1970s, I was introduced to an RAI National Network high official, usually a politically assigned post, who sat me in his handsome office and asked point-blank: “You are a…very close friend of Maestro Ellington, I am told?”

Surprised, yet amused, I explained: “You could say that we are very good friends but not ‘very close’ the way you mean…”

Taken aback, he fidgeted with his Montblanc pen. “Ah, I had been told…but no matter, if you are good friends then you will no doubt obtain for us that he comes to play his Sacred Concert for the Holy Father?”

This time I was the one to be taken aback. “Perform a concert in the Vatican for the Holy Father?”

“Yes. You must know that each year RAI offers the Holy Father a special concert. As a rule, it would be in the realm of classic music, with some prominent artists. However, we have heard some very interesting comments regarding Ellington's sacred music coming from the classic milieu itself.”

“Ah, well for that matter I myself have witnessed a very brotherly greeting between Ellington and Herbert von Karajan…”

“Exactly. Therefore, we have decided that a performance of Ellington's Sacred Concert would be most appropriate.”

“Actually, he has composed two Sacred Concerts, and I do believe he is working on a third one. Would that be of interest? I mean, a command performance of his Third Sacred Concert?”

I could tell the man was extremely interested and kept scribbling on a piece of paper. I went on, musing aloud. “Of course, it depends on various aspects. On how soon the third concert will be ready to go on the road. On what former engagements his agent has already accepted. As well, of course, as the possible date of the Vatican concert?”

A phone call was made and he obtained an appointment with the Vatican authorities.

A few days later I was walking alongside the director, enjoying the architectural beauty of the Vatican. When we reached the doors of the office in question, I was kindly asked to sit in a handsome armchair and wait. As I sat there, I thought of Ellington's recent interview where the journalist had asked him if—having, at his age, been blessed by all sorts of honors, fortune, wealth, and success—there was yet one more gift that he wished to receive from life? Ellington had considered the question and then answered that perhaps the most important moment of his life would be…to be allowed to present his last Sacred Concert to the Holy Father, within the Vatican walls.

Eventually the RAI director reemerged, smiling primly. No comment from him while we walked out of the Vatican buildings. Then, finally, yes! It could be done! I was now to speak with Ellington and find out what was the situation on his side. No date was fixed yet, not before quite a few months. But I could start the ball rolling.

However, I hesitated to contact Ellington yet. My long years of working with the RAI authorities had taught me that sometimes an enthusiastically conceived project could end thrown out the window for a number of reasons: a political change of management, new budget restrictions, anything and everything. I told the director that I would contact Ellington as soon as I received an official letter from RAI asking me to do so.

It was fortunate I did hesitate, for the letter never arrived and, a few months later, the director called me again in his office. Very embarrassed, he informed me that, due to the terrible famine that was ravaging India for some time now, the Vatican had decided to annul all forms of entertainment, obviously including Ellington's Sacred Concert. I was heartsick but relieved that my friend would never have to share my disappointment.

ACT IX—FINAL INTERVIEW

In 1969 the RAI Television producer of a very popular series called “Un volto, una storia”—literally, “One Face, One Story”—asked me if I would be interested in producing a special number for that series, dedicated to Duke Ellington.

Considering the fact that the whole series seemed dedicated to sad, tragic, unfortunate subjects with a story that was certain to be a tearjerker, often relieved by an unexpected happy ending, I told the producer that Ellington's story was anything but that of a poor black underdog who eventually acquired fame.

The man listened to me, a little disappointed at first, and then with a smile he assured me that the very fact of Ellington's fortunate life, practically from birth, would be the catching “story” of that “face.” Would I please contact Ellington right away to find out his fee and a date of his choice, for the filming?

With his usual benevolence, Ellington listened to my proposal on the phone. He then asked if I would have complete and direct responsibility for the whole project; he then accepted, refusing any fee. The date he chose coincided with his coming Italian concert tour within a few weeks.

“I'll see you in Bari, my Lil; you can come and film the interview at my hotel suite after the concert, for as long as you need. I'll add just one thing. I want a contract from RAI that mentions clearly that you have the total control and approval of the operation. Will they do it?”

Of course they were willing to promise him the moon! They could have Ellington on their program and at no fee? Quick with the contract, yes, let la Terry have the last official approval, they could see no problem with me.

Thus, one fine day I was in an RAI car with the director, the cameraman, and the sound technician, on our way from Rome to Bari.

I described the fascinating personality of our famous artist, and from their questions I was amused to note that they suspected that only a very close “affectionate” relationship between us would induce such a personality to concede a TV interview deep into the night, after a concert, and at no fee. I was even more amused by the look on their faces when Ellington greeted me with his usual “total embrace.”

“Uncle Eddie, I want you to know that this is a huge gift you are giving me, and I do appreciate it. Let me introduce my colleagues who are thrilled to work with you…”

My three TV crewmembers had come forward, and Ellington was immediately charming them with his wit and what Italian language he knew. It was decided that we would tape the interview at his hotel suite, right after the concert.

So around one o'clock in the morning the scene was set, lights appropriately fixed, a microphone hovering above us, out of sight. Relaxed and amused, Ellington answered at length the questions that the TV director and I would ask him, regarding both his personal life as well as his career. The picture that emerged was obviously unique.

He spoke of his father, who had worked as a draftsman in the Navy's printing office but also doubled as butler for high-ranking families in Washington. This last occupation had resulted in a certain genteel reflection in their own home, with proper silverware, furniture, and good manners that were taught to the children. Both parents, as well as his sister Ruth, played the piano.