ABBEY LINCOLN AND MAX ROACH

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach were undoubtedly the most interesting couple of modern jazz. They were brilliant and intelligent, and we are all aware of their artistic accomplishments as well as the political and social importance they were deservedly given. For my part, I can speak of them remembering the friendship that developed between our two families, from our first “business” meeting in Milano and on through all the years that followed.

ACT I—ABBEY LINCOLN AND MAX ROACH

In the summer of 1967 Max was invited to Milano by Meazzi—Italy's leading percussion firm—to discuss his endorsement of their Hollywood Tronic Drum. When Meazzi invited me as well, the idea of meeting Max and Abbey was most stimulating, for I had been aware of the couple's involvement in the political scene of the United States from their first Long Play, “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite,” and their social involvement in the Black Power movement had been of great interest to all of us.

The Meazzi director had asked me to act as his hostess with the couple, who stood, tall and very handsome, among admiring Italian musicians and journalists. Everybody was eager to hear this odd Tronic Drum boom into life at the magic hands of one of the great drummers of all time, and I could tell our artists felt slightly out of place in this typically noisy and good-natured Italian crowd.

When we were introduced formally, Abbey and I measured each other with feminine curiosity. I smiled at her, admiring her African headdress.

“You know, that turban will be the envy of all the fancy Milanese ladies at today's luncheon, especially as they could never hope to wear it with the same results. Actually, you and Max are a very handsome couple. Another thing, your record covers don't do you justice. You're much more interesting in real life.”

Shaking hands with me with an amused smile, they accepted my compliment and Abbey asked: “Oh yes? Well thank you. And which records do you refer to?”

“Good Heavens! I'm a mess with titles of LPs but, of course, I do recall the ‘Freedom Now Suite’ and especially the one called ‘Abbey is Blue.’ I am always playing on my radio program your version of Kurt Weil's ‘Lost in the Stars.’ With that lightly rasping voice you have, it really gives the lonely feeling of those lyrics.”

“Yes, it's one of my favorites.”

She was amused by my outspokenness. We talked for a while about African clothes and the way they were being worn by black Americans as a political statement, and I could see that she was trying to figure me out. “Where are you from?” she asked suddenly, “You're not European…”

“Nope, I was born and raised in Egypt, but my father was Maltese and my mother is Italian. You might say I am Mediterranean.”

She shook her head, amused, and exclaimed, “You know, what you really are…is a mess!”

“I just told you so; but then, why not?”

She asked, pointing a finger at me, “So you are not a Soul Sister…?”

“No, my dear, but I am a Sister of the Soul.”

“I love that!” She laughed out “A Sister of the Soul!”

And with that phrase our friendship was set. There were no more barriers between us but instead a light teasing camaraderie.

A few days later they came to Rome, where my mother and son were eager to meet them. Mother admired their looks and their elegance, declaring Abbey “Una Dea Africana,” an African goddess. As for Max—mother always had a weakness for tall, strong men—she said, “You are the powerful African lion, the king of the forest!” My seven-year-old son Francesco sat next to Abbey in speechless admiration.

The next day we went to the beach at Fregene, and while Abbey and I stretched in the sun gossiping, Max took Francesco by the hand, asking for his assistance at the ice cream stand. They were gone for some time, and when they reappeared Francesco was nursing in his arms a huge motorboat, grinning from ear to ear. I scolded Max for spoiling him, but he shook his head, saying, “Francesco said something to me in Italian that I didn't quite catch. It was about black and white people, I think?”

Francesco repeated his Italian phrase so I could translate it for my two very attentive friends.

“I said that I know now the difference between black and white people…”

“And?” asked Abbey, cautiously.

“Well, black people have a very kind heart and treat children much better than white people do!”

She gave him her special harsh laugh, pulling him onto her lap and, rocking him, she said:

“Well, bless your little heart, Francesco!”

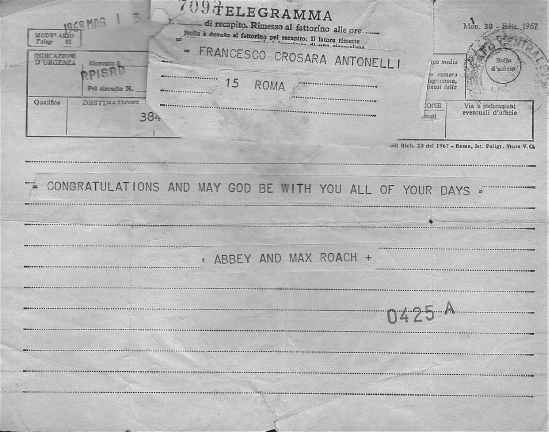

A year later, when Francesco was given his First Communion in Rome, he received a personal cable from New York congratulating him for this very important day of his spiritual life: “Congratulations and may God be with you all of your days, signed Abbey and Max Roach.” And that's how a bond was created that grew and strengthened between our two families.

Yes, through all the remaining years I was their “sister of the soul” through the joys and pain they shared and inflicted on each other, especially with their divorce. It was obvious they never stopped loving each other, long after they had each developed a new, separate life of their own. And I was grateful to be able to enjoy their friendship equally for the rest of their lives.

ACT II—SISTER OF THE SOUL

Across the years Abbey and I had established a pattern. During her tours in Italy she would come and rest at our country home near Venice, where mother would ply her with tasty goodies while giving her wise advice on how to treat men in general. In turn, it became customary that I accept her hospitality at her New York apartment at 415 Central Park West—and later in Harlem at 940 St. Nicholas Avenue. In New York I would cook special pasta dishes for her, on condition that she should also eat vegetables, which were not her favorites.

We would always find the time to “take our shoes off” and curl up in our armchairs to talk. She would laugh, grumble, criticize but above all review her life, her mistakes and her hopes, her defeats and her victories. Gradually I could put together her history from the 1950s starting with her extraordinary evolution from a pretty, sophisticated pop singer called Gaby Wooldridge or Gaby Lee—who charmed the patrons of supper clubs in Honolulu for a few years and then moved on to conquer the Big Apple—to bloom finally into Abbey Lincoln.

Riverside records began recording her evolution toward a more jazz-oriented repertoire, and in 1957 the same Riverside studios were witness to the birth of an inevitable earthquake when Abbey Lincoln met Max Roach. By the time they were finally married in 1962, she was well on the way to becoming politicized, as shown by her deliberate Angela Davis afro, and later the African braids.

Abbey admitted that Max had opened her door of perception to the events going on around them, socially, politically, and culturally. She became aware that being an attractive jazz singer was not enough; in fact, she rejected that definition, choosing “black artist” instead. With Max she became interested in the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, joined actively most of the public protest meetings, such as the one at the United Nations regarding the murder in 1961 of Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of the new Democratic Republic of Congo.

In 1968 she phoned her excitement regarding the film she was about to act in: For Love of Ivy with Sidney Poitier and, some time later, her joy at the success of that film. In 1969 the film had obtained her nomination for the Golden Globe award.

That success and recognition, however, did not spare her one huge disappointment she endured. One day we had gone downtown to celebrate great news with her friends. She had been interviewed for the role of her dreams: the life of Billie Holiday! We all felt certain that the outcome would be positive, for she was evidently the one actress-singer who would represent Billie to perfection, not only for the particular quality of her voice and her singing style, but also as far as stark physical appearance.

It could only be Abbey Lincoln. The word went around and everybody congratulated her. But Diana Ross decided she wanted that role and obtained it, turning Billie Holiday into a “Supreme” eye-batting doll.

But Abbey was a strong spirit, and the deep disappointment somehow enhanced her will to express herself with all the means that nature had generously bestowed upon her. She was a musician and a poetess, a writer, a performer, and also a painter. Above all, she lived her life battling for her social ideals.

Our discussions, in either of our homes, were always filled with frustration at the unfairness of the world and finding comfort in the end as we managed to laugh at life, at our men, and mostly at ourselves and our illusions that we could save humankind.

ACT III—SEPARATION

In 1970 came the painful, reluctant separation from Max Roach. It touched Abbey deeply, and for some time she was unable to move away from the building where they now both lived in separate apartments, as if she were hoping for a possible reunion.

“I'm an ‘eyes wide-open’ fool, Lilian. But I can't believe that there's nothing left between us; after all we have lived through together, the political battles, creating our music, loving each other totally…. When I think of those horrible years when his mind was shot to hell and he was going down the drain; yet I stayed with him, by his side, facing together each stage of his cure…. And, when he was finally out of the woods, that's when I broke down and went to pieces in my turn and, would you believe it? Roach left on a long international tour…. He was strong enough not to need me anymore, but what about me? I needed him; I still do, damn it!”

Then in 1975 she phoned that she was going to visit my homeland, adding “sort of.” Miriam Makeba was leading her into the heart of Africa to discover her roots. From that extraordinary voyage she had emerged more set than ever in her battle in favor of the underprivileged, of whatever race. In Africa she had also been given a new name: Aminata Moseka.

Sometime after the divorce Abbey moved back to California, where her family resided. Incidentally, by then my grown-up Francesco had entered USC in Los Angeles and was very dedicated to his jazz piano. Abbey, who lived in West Los Angeles, would meet him regularly, and he would work with her, transcribing her songs—melody, chords, and text—onto music paper with his neat Virgo scores. They also composed a song together, a  tempo called “Children.”

tempo called “Children.”

After she returned to New York at the end of 1982, she further developed her writing and painting skills. In 1983 Francesco, invited to spend his spring break at her home, now in Harlem, had sent me an enthusiastic description of the night when she had sung at the Harlem Apollo Theater, accompanied by pianist Cedar Walton. Francesco had mentioned the huge black limousine driving them to the theater with equally huge black bodyguards. Through the years, they were in regular contact. She would speak to him about “Roach” when she referred to Max; and about Black Power, referring to the whites as “the Europeans” and to the blacks as “the Africans.” And, of course, she spoke to him of oppression and emancipation; she was as indignant and angry as ever at the social situation, especially regarding the old “bag ladies” who trailed in the streets.

When Francesco became a husband and father, living in New Jersey at the time, Abbey was present in church for the baptism of his baby Alice. When many years later Francesco was living again in Los Angeles, he used every business travel occasion to drop in on Abbey in New York. His last visit was in 2005, when she was living again on Riverside Drive.

He wrote that her sight was failing her, that she had seemed particularly fragile and a little absentminded. She had proudly shown him her “naïf” paintings inspired by African subjects in bright jungle colors. She was always as beautiful and as angry at racism as ever, especially with regard to the milieu of music and the arts. He finally mentioned that she did not seem at all in good health, and he was worried he might not have the chance to see her again.

In fact, in 2007 she was undergoing open-heart surgery.

ACT IV—MEMORIES

We have so many memories of that wonderful woman, such as the time I had recorded a successful LP with Tommy Flanagan in 1982. One day, in Rome, I had received her call from New York to tell me that WBGO, the New Jersey radio station, kept playing the whole LP from top to bottom and daily. She had thought it would please me to know it and that she loved it. The next year she sent me her latest LP, “Talking to the Sun,” scribbling on the back:

“Dearest Lilian, I love you for everything you are. Thank you for friendship. It's love. Abbey Aminata Anna Marie.”

I have it right here on hand, today.

At Count Basie's funeral in April 1984, I had been Abbey's guest in Harlem. Calling Dizzy Gillespie on the phone, we had made a date for the next day, when we would meet him at the Abyssinian Church in Harlem and, after the funeral, he would come to Abbey's home for his special “pasta” lunch. When we got there, Dizzy was immediately grabbed and ushered into the church. There was such a huge crowd trying to enter that Abbey chose for us to join the many other fans and friends in a bar just across from the Abyssinian Church, to have a drink to Bill Basie's memory instead.

Finally, Dizzy, Abbey, and I were at her home and, while I went into the kitchen to prepare “farfalle, pisellini e gamberetti” (butterfly pasta, sweet peas, and baby shrimp) and Abbey set the table, Dizzy sat at the piano and played romantic ballads for us.

At lunch we spoke of various things, remembered some of our friends who had gone ahead, others who we had been glad to discover were still alive; in all, it was a very relaxed, philosophically thoughtful afternoon.

During Abbey's European tours we would often organize some concerts also in Italy. In Sorrento I had organized for a huge banner to span the main avenue from side to side with the largest words to read “Welcome Abbey Lincoln.” Driving into Sorrento, there it was, flapping its greeting to her. She had gasped then exploded in her brilliant laughter. “Oh, I love it! I love it!”

When the jazz milieu of New York finally realized her worth, the Lincoln Center organized a series of concerts in her honor at the Alice Tully Hall. On the phone she was very happy, on the one hand, yet melancholy. I wrote her a note of congratulations:

“I am sure that during these coming evenings at the Alice Tully Hall you'll be thrilled and excited and will be your beautiful overwhelming self. How very appropriate that they should honor you, considering what you represent not only for jazz but also for the dignity of women anywhere in the world. Am very proud of you, my girl, and trust you will contact me as soon as you are relaxed enough to sit and write all about it.”

Of course she preferred to answer by phone.

ACT V—LAST MESSAGES

My last message to her, typed in large letters to ease her failing sight, went as follows:

Happy Birthday, Anna Marie, Gaby, Abbey or Aminata!

As I told you in my phone message, the French/German TV station ARTE passed a long Special dedicated to you, recorded a few years ago. It was wonderful to watch you sing, talk, laugh that brilliant laugh of yours—and so touching to see that you can still get tears in those eyes—that I got homesick for our old times together. If we could talk (and laugh) so meaningfully years ago when we still had a lot of living and learning to do, can you imagine our future get-together?

It was extremely interesting to see your paintings and just what exactly went on between you and Jean-Philippe Allard, hum? I was very moved by your rendition—in French, I say!—of the famous song by Léo Ferré, “Avec le temps.” Actually, with your contract with Universal you have become practically French! I love your latest “Abbey Sings Abbey” but although I love all your songs, the one I like “very best” is “Throw It Away” of course. As for me, as you know our CD “Emotions” comes out in September and I wish you were here for good luck! Francesco did a very good job as pianist, arranger, and producer. But then he was a pupil of yours.

From September onwards I'll be living definitely in Nice and I hope to have you here, during your French excursions, if only to eat all the veggies you love so much…Of course including foie gras and champagne…OK, now the ball is in your corner. I enclose a magazine cutting regarding your TV presentation, for your files.

Love, as ever, from your sister of the soul.

When she did answer by phone, she told me that while she sent me all her love she also considered it unlikely that we would ever meet again in person.

It was so. On August 14, 2010, our beautiful girl left us with the poignant memory of a very special and unforgettable human being. She was an extraordinary artist as a singer or poetess, actress or painter. She wore her heart and soul on her sleeve as shown by the text of her songs; and she never stopped caring for the “underdog,” expressing her anger on their behalf.

Our favorite song remains “Throw It Away,” and we can see her radiant smile as she sang it:

Throw it away, you can throw it away!

Live your life. Give your love, each and every day.

And keep your hand wide open, and let the sun shine through.

For you can never lose a thing, if it belongs to you.”

Abbey Lincoln was much loved by all who knew her: man, woman, and child. She was unique, irreplaceable, and is forever missed.

ACT VI—THE AFRICAN LION

When Max and Abbey parted, I was relieved to see that my relationship with either of them continued unhindered by their reciprocal problems. Max remained our very good friend, and we enjoyed both his company and his music for the rest of his life.

He was obviously a charmer with his sharp sense of humor and his brilliant mind. His art—both as composer as well as performer—was definitely outstanding, growing through the years in the eyes of critics and public alike, the world over.

As mentioned, our friendship had begun in 1967 in Milano, through the Meazzi Company, who then invited me to the Chicago Music Fair in 1968, where Max was presenting their Hollywood Tronic Drum. Obviously, Max attracted a very large amount of public attention as he sat regally powerful, explaining the very complicated secrets of an electronic set of drums. The Meazzi engineer stood by his side, ready to give further insight into the workings of the instrument, in Italian, while I translated into English what I hoped was a coherent spiel.

It worked enough to impress Max, who decided, through the many years that followed, that, whenever I was free, I would be his assistant in Italy during his seminars and clinics. I would explain his lessons in Italian and act as interpreter between his questioning students and the Maestro Massimo Roach. I remember that he would close each lesson by playing for his admiring students his particular version of Chopin's “Minute Waltz” on his drum set, provoking their enthusiastic applause. In Italy I also organized some concerts and radio and television appearances for him.

On the other hand, during my visits to the United States he was ready to accompany me whenever I requested his assistance to approach particular artists for my radio program. We were often joined by Papa Jo Jones, as when we would go for a good soul-food meal at the Boondocks, or the time they drove me by car to the Newport Jazz Festival and we ended up as guests of Lucky Luciano's brother-in-law at the Cliff Walk Manor. Here is what happened.

We were driving from New York to Newport in a pale blue convertible car. We were enjoying the ride, listening to Otis Redding and singing along with him, approximately, and at the top of our voices: “Oh, I don't know what you're doing to me, baby, but you're so GOOD to me!” I was there to tape—for my Italian Radio program—a number of interviews with any jazz artist I could approach during the festival. Max had patted my shoulder reassuringly: no problem, I was to pick out any artist I fancied and just point him out.

At the Newport Motel—where the Italian Radio office in New York had reserved three rooms for Terry, Roach, and Jones—the reception clerk told me, after eyeing my two suntanned friends, that unfortunately they had only one room left, for me. Yes, three rooms had been confirmed but it just so happened that…

Indignant, I had walked out with Max and Papa Jo, who warned me that it might be impossible to find rooms anywhere else at that point of the festival. And right they were; not even George Wein could help us, at least not for that first night.

“Better go back to the motel, Lilian. Don't worry, we'll find a pad.”

“Never! We came together, we share together. This is my first personal contact with discrimination, and we're in 1968! They'll never believe it in Italy when I tell them!”

“Italy!” exclaimed Max to Papa Jo, who answered: “Sure. Nick!”

And with those mysterious words they drove me out of town to a beautiful cliff with a breathtaking view of the ocean and an elegant hotel called the Cliff Walk Manor.

“What a lovely place! Look, the sign says the hotel is closed. Yet look at all those limousines…. They must be having a wedding.”

Max and Jo exchanged a knowing grin, nodding, and then Max turned to me: “Well, Lilianah, looks like you're going to have another American experience. You're going to be the guest of a very important family. I guess we've run smack into one of their reunions. I'll go find out.”

While waiting for Max to return, I asked Papa Jo the name of this family, but he laughed and shook his head: “Just you wait, girl.”

Within minutes Max was back, waving for us to emerge from the car.

Flanked by my two artists, I entered the large hall where a very friendly man by the name of Nick Cannarozzi came to greet us.

“Say, great! Nice to meet you! So you're from Rome, ha? Come on in and meet the folks! We've just finished lunch and they're eager to meet you.”

I was ushered into the center of the huge dining room where I saw a number of men and women, all dressed up, sitting at ease around an imposing horseshoe-shaped dining table. I considered that this was a rather large crowd to belong to just one family…

Meanwhile Nick Cannarozzi was being a perfect host, introducing me around, and everyone was happy, glad, delighted, and pleased to meet me…and what was new in Rome…and when had I last seen the Pope? Shaking hands and answering with a smile, I raised my brows at Max and Jo, who were standing back with huge grins on their faces.

To cut a story short, the three of us were made welcome to stay as guests at the top floor of the Manor for as long as we liked. It was understood that we would use the other entrance and be discreetly invisible.

It was only the next afternoon, when we had found accommodations elsewhere, that Max told me, greatly amused, that we had been the guests of Lucky Luciano's brother-in-law, in the midst of an important Family business reunion.

My heartfelt comment was: “Well, I'll tell you one thing. If it hadn't been for Nick, we would have ended up sleeping in the car. Long live Nick Cannarozzi and Italo-American hospitality!”

During those four days in Newport I saw many old friends and made some new ones, like Joe Zawinul and Cannonball Adderley. There was also Ray Charles, who accepted willingly to give me an interview in New York some days later and from which meeting there developed a long and lasting friendship, across the continents, for more than a decade. But that's another story.

Max Roach was my mentor and my guiding spirit in Newport as he saw to it that I should meet all the famous artists I wished to include in my Italian Radio program. I interviewed Mahalia Jackson and Bill Basie, Dizzy Gillespie and underrated saxophonist Vi Redd. I taped a very pleasant interview with Tal Farlow and Barney Kessel. My greatest prize, however, was when Max introduced me to Nina Simone as his “sister of the soul” from Egypt. He obtained that she consider me with friendly curiosity, resulting in an invitation to her home in New York. An exceptional interview was recorded on that occasion.

ACT VII—UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AT AMHERST

When Max became a faculty member of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, I was truly happy for this well-deserved recognition, and we celebrated when he came to Italy. I could not help wondering if, being now part of the Educational Establishment, his outlook regarding the racial situation had modified.

In one of our “conversations” for my radio program I questioned him about it.

“Massimo, today that jazz is being played all over the place, in all countries, all continents, therefore by all races…can one still say that there is a white way and a black way of playing jazz?”

He obviously loved that question!

“Well, let's examine jazz itself, from a musical but also a political vantage. Jazz is the most democratic form of any music on the face of the earth today. It deals with racial participation, racial contributions, et cetera. Jazz is the complete opposite of European classical music, in the way it is performed and created. Classical music is imperialistic in its political nature. There are two main people involved: the composer and the conductor. The rest of the orchestra, singers and all, are no more than robots doing the will of these two characters. That's why I say imperialistic.”

“Whereas jazz is…?”

“Whereas jazz is democratic in the fact that everyone has a voice in the makeup of the composition itself. There may be a composer…say Mister Ellington, or Gershwin…. We may use one of their pieces as a theme, but we have an opportunity to develop that theme the way we feel about the subject, provided we stay in the boundaries of the harmonic, rhythmic, and melodic structure of that particular piece. That we preserve the ambiance of the piece: exiting or peaceful, whatever. It's democratic because we are free to express ourselves within those boundaries. That's why the music itself is so attractive to so many musicians around the world.”

“But they have to learn the rules…”

“And it's no small matter either! A lot of people think improvisation is just where you do what you want to do. But certain structures are set up, and you have to be able to improvise within these musical guidelines. And even though it's free, it's really not free. There must be harmony among the group as the whole performance has to get on; we are all free to participate but…intelligently. So our music expresses what true democracy is because it's the music that comes from ordinary people, regardless of race. It's not an elitist type of music.”

“Although many people will say that jazz is an elite music, for an elite public.”

“Yeah, those who see this as an elitist type of music are usually middle-class and bourgeois. But jazz came out of the creativity of people who were not of the elite, it came from the bowels and guts of the working-class people, of every persuasion—people who have created a culture that is viable and just as technical. It has its own laws about perfection, and about what makes the true jazz artist.”

“Following precise standards?”

“We do have standards by which we evaluate a person.”

At that point I remembered that Max had begun to play the drums at a very young age, soon becoming a recognized performer when he had joined the new bebop scene.

I asked him if he had ever studied percussion academically.

He answered, grinning, “I had quite an experience, you know, when I decided to go to the Conservatory in New York City.”

“How old were you?”

“Well, I guess I was about twenty.”

“And how long had you been playing?”

“I started playing when I was still in school because in New York City at the time…music abounded in every nook and cranny, out of the walls, twenty-four hours a day. I'd been making all these records and things…this was in 1944/45. So I said, “I'll take an audition to get into the Conservatory,” and naturally my instrument would be drums; though I had been playing piano since I was very young, from the church.”

“So you're also a pianist, like Dizzy!”

Nodding, he went on with his story:

“When I went to the professor—his name was Albright, a famous teacher—he gave me the sticks, put some music before me, and told me to read it. So I picked up the sticks…and before I could even strike the drum, he told me I was holding the sticks incorrectly! Now I was paying my way through this very school by working on Fifty-Second Street making records with people like Coleman Hawkins, Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie…playing the drums, the way I play the drums.”

“Well, of course!”

“Now that was not an insult to me, for right then and there I changed my major to composition, which was really a blessing. And it taught me several things about the United States.”

“Such as?”

“First of all, that although we have several cultures here, the only one recognized is the Germanic culture. We only speak one language even though we have a nation of Italians, of French, Chinese, Japanese, all kinds of people. We should know more about folks who live next door. Know something about Asiatic cultures, about different European cultures, but we are only taught one culture and this is my big fight since I'm in education now. The United States are one-dimensional, culturally speaking. And it's a tragedy.”

He shook his head. I moved the subject forward.

“So when you changed your musical studies…?”

“Well, I changed my major to composition, and I smiled because I knew that with Mister Albright's military technique for classical music…well, there would be no way I could use that technique down on Fifty-Second Street and perform with people like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie! They'd drive me off the stage, of course!”

We laughed, imagining the scene.

He went back to the original subject:

“Many students ask me, like you did: Is there such a thing as black and white jazz? Now in my lectures, especially in the United States, I talk about the history of the music and the major contributors to different styles and different periods of the music. Almost always, they are black, and there's a reason for this, Lilian, because the seed of this music is in the United States of America. Nowhere in Africa do you hear this kind of music, or in the history of European music, or Asiatic music. It's peculiar to the United States of America, because it's a fusion of all these cultures; although the U.S. itself denies these cultures. They say the only thing that's valid is the Germanic culture: English, Shakespeare, Bach, Beethoven, they call this ‘high’ culture.”

“And what do you teach your students?”

“My students ask me: ‘We've listened to your lecture and very seldom do you mention the contribution of white musicians,’ and I say there's a political reason for that. A culture is a result of a way of life, of your family life, the things that your sensibilities are bombarded with from the time you come out of your mother's womb, until you become an adult. What I'm saying is: In the U.S.A. blacks were not allowed by law to participate in the white way of life, become part of the white part of town. And whites were not allowed to become part of the black part of town. We all know that Bessie Smith died when she was in an automobile accident, down there in the Deep South. The first ambulance that came was from a white hospital, but they could not take her legally; they had to go back and she had to wait for an ambulance from a black hospital, and that is why she died.”

“Yes, such a tragedy!”

“So whites were not allowed on our side of town…and we weren't allowed to go to theirs. Consequently, we have produced no Beethovens or Bachs, or Gunther Schullers, and by the same token whites have not produced any Charlie Parkers or Billie Holidays. This is a sociological and a political problem.”

“Even today?”

“Today of course that condition is lessened because people are becoming more civilized, in the United States. We learn to live in close proximity to one another. But the beauty of this music is that, even before racial segregation became illegal, boundaries had been crossed earlier. It's because Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke and all these people intermingled, in spite of the segregation laws.”

“Thanks to jazz.”

“Thanks to jazz. It started many, many years ago. Take the techniques that are essential with jazz, on a professional level; everybody had a hand in that: Europeans, Africans, everybody. From the instrumental standpoint, from a harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic standpoint. So it's really a combination of that democratic process that's supposed to exist in the United States of America.”

“Supposed to exist?”

“Supposed to exist. But jazz really personifies it. I can get on a bandstand with Zoot Sims, Stan Getz, Miles Davis, and Ray Brown; and something happens, something really happens, because we all know the techniques that are involved in making this music a living piece that has high order, design, and form. It has clarity: a beginning, a development, and an end.”

Listening to his reasoning, I couldn't help thinking with some amusement at how his strong personality must have affected some of the formal classical professors when he became one of them at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. So I asked him, hoping for an interesting reaction. He reacted.

“With my cohorts, who are music professors themselves, we have faculty concerts during the semester. Sometimes they do an “improvisational piece” but with music in front of them that will say…to the percussion part: “throw a dime up in the air and let it drop on the snare drum and then dampen it.”

“And this is improvisation?”

“This is improvisation. Or: ‘Play a series of four eight-note phrases, but in this three-minute period you cannot use the same type of stick as a percussionist.’ That means you play ‘da-da-da-da’ with a brush, ‘da-da-da-da’ with a mallet, and then ‘da-da-da-da’ with something else.”

“And that's improvisation!”

“That's improvisation. Now, as far as the voice part is concerned…”

“Yes?!”

“You get the telephone book…”

“Oh, come on!”

“It's true, this is a piece now. And for one minute you read the names at random from any page in the book. Then from any other page, at random, for thirty seconds. While this is going on, the trumpet player may be doing something or other. This is their improvisation. Now jazz is not like that.”

“I should say not…”

“In jazz the properties are all laid out and we all know the law. Like in a democracy, everybody has to be intelligent enough to know that we have to govern these properties together, equally, and that's what jazz is about. And the reason it came about in America is because the U.S.A. is, on paper, a democracy. It's a reality because a common man can become a president, like Richard Nixon…or Gerald Ford. There's no “upper class by birth” in the United States, so it has eliminated the imperialistic quality of the country, and our music personifies that attitude, politically. It originated in the U.S.A. and then spread out to the world where there are some people who may do a better job than the originator.”

“But would you still call it jazz at that point?”

“If we're going to deal with just labels…I think music is the proper term”

“Afro-American music?”

“I don't call it Afro-American music now. You see, we named it Afro-American or black music as a reaction to the social system that was there then. We, as black people in the United States, were always denied everything. So in order to fight back we'd say ‘well, this is black music!’ you understand? Because everything else is white, it's tacitly understood. So, ‘Afro-American music’ or ‘black music’ is a reactionary statement. This music is made of a combination of cultures that exist in—and could only have existed—in the United States.”

“Yes, but then would you say that there is a white way and a black way of playing jazz? That they are similar but different?”

“Well, are there a ‘white European classical music and a black European classical music?’ I mean, we have a lot of blacks who come out of the conservatory and write wonderful music but who would know of any great black composers in the European classical music tradition? Most people would say ‘I don't know of any.’”

“That's true.”

“So I say to you: Lilian, when you look at the history, at the development of our music, it's almost totally black. Now, usually this insults a lot of white people, and right away they cry ‘racism!’ But we'll just look at the history of the trumpet, for example. We'll say: King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, Hot Lips Page, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Freddie Hubbard. Now why didn't I say Bix Beiderbecke, Chet Baker, Harry James, Red Rodney…why didn't I say that?”

“Why didn't you?”

“Well, it's obvious. Red Rodney was influenced by Dizzy Gillespie; Chet Baker was influenced by Miles Davis. I'm talking about the original people, OK? So now when I listen to black composers who compose in the European classical tradition, I hear a little Stravinsky, a little Debussy…. So I would not say they now are as great as any European composer; there's no way in the world I could say that. The question I am trying to answer to you…I have had so many debates, even here in Italy, and I have been accused of being a racist when it comes down to culture…”

I have to laugh.

“No, don't laugh; I'm very serious about this. I maintain that whites have not had an opportunity to really become involved in jazz on as serious levels as blacks. Because if we want to participate in music seriously, we have to become engaged in jazz music, whereas Europeans can become engaged in European classical music and ‘incidentally’ become involved in jazz music as well. As fine a musician and as creative a musician as Mister Ellington is—and as much music as he has written—he is still classified as a ‘jazz’ musician. And I might also tell you that Duke Ellington never referred to his music as jazz.”

“I know! He would ask, ‘What is jazz?’”

“Mister Louis Armstrong never did either; he called it: ‘This is New Orleans style.’ A lot of these names don't mean that much anyway, they come and go. So when you say ‘jazz,’ it's a cover up for everything. Who is jazz? What is jazz? The King of Jazz is Paul Whiteman!”

I burst out laughing, nodding. Max continues:

“That's the truth. Historically, the King of Jazz is Paul Whiteman. The King of Swing is…” (we name him together) ‘Benny Goodman!’”

“But why is it so?” I ask him.

“Well, publicity! Somebody says that. When you listen to someone like Eubie Blake expound on the music, and the forms of it…you learn that jazz came as a later word. Another thing, they had soul music, rhythm and blues music and all of a sudden they changed it to rock and roll. Now when they have the big contest about who sold the most records…well, in the rock category there are no black people. Black people are relegated to what they call soul and rhythm and blues. So right at this point in time things are really a bit confused.”

The tape had come to an end. We agreed we had a lot of very satisfying material on record, so we let it go at that, and I drove him home, where mother had prepared a very special Italian meal for him.

ACT VIII—FAMILY TIES

His relationship with my family continued through the years. Max was always ready to welcome Francesco whenever his concerts coincided with my son's whereabouts. In 1982 I would receive enthusiastic reports about Max playing at a club on Washington Avenue in Venice Beach. On that occasion Max had invited Francesco to his beach apartment on Manhattan Beach. My son had noted dutifully that Max, very casually dressed at his beach home, had then appeared on the club stage impeccably dressed in an Armani suit! He also described the complex, sophisticated arrangements, such as “Round Midnight,” played with a highly interesting fast swing.

The last time they were together—some years later when Max had been integrated at the University at Amherst—he had invited my son to his home in Greenwich, Connecticut. There, Francesco had met his daughter Maxine, who was playing cello in a string quartet, and his son Raoul, a very busy producer. Max discussed his last project, “M Boom,” and gave Francesco one of the first CDs coming out.

There was just one melancholy observation from my sentimental son: while at every meeting Abbey would sooner or later mention “Roach,” as she called Max, since their divorce Max had never once mentioned her name.

One vision that will never fade is that of the magic concert held in the breathtaking Arena of Verona. There were only three names on the large poster, and they were three exceptional artists: Dizzy Gillespie and his United Nations Orchestra; Miles Davis and his most recent experiment; Max Roach with his “M Boom,” including Maxine Roach and her string quartet.

The last time Max Roach and I were together was in September 1987 in Bassano del Grappa, where Dizzy Gillespie had adopted my Popular School of Music, giving it his name and with a regular annual appearance of encouragement among our enthusiastic students. The occasion of that last meeting, officially named “Dizzy's Day,” was most important to all of us. The City of Bassano had decided to give Dizzy an honorary citizenship, and at the same time I was to produce our official celebration of Dizzy's seventieth birthday with a huge concert at the Velodrome with about eighty international jazz musicians and more than five thousand fans gathered together to celebrate our artist.

From the United States I had immediately invited Max and Milt Jackson, plus Randy Brecker and Johnny Griffin, who lived in France. There were musicians from Spain, Switzerland, Yugoslavia, Denmark…they came for Dizzy, and the music flowed from 6 P.M. to 3 A.M.

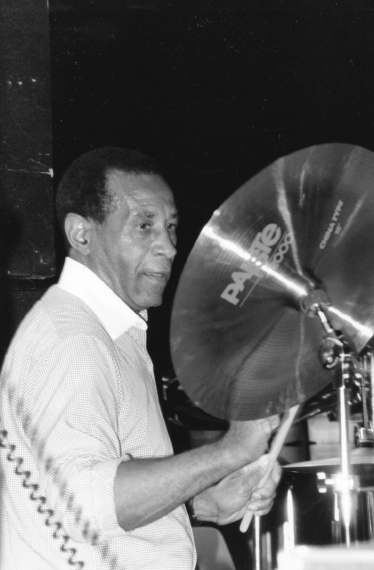

Being in charge of the whole operation, I was unable to spend all the time I wished with my closest friends, but the obvious mutual pleasure of being all together was rewarding enough. My last visual memory of Max Roach is that of a handsome man sitting powerfully at his drums, giving the heartbeat to the music and to thousands of enthusiastic fans.

Max left us on August 16, 2007. Three years later, almost to the day, on August 14, 2010, our beautiful Abbey said goodbye. Somehow, we have never been able to really think of them as two separate individuals, even after the many years that followed their divorce.

They gave my family their affection and their trust, and I was fortunate indeed to be considered their “sister of the soul.”

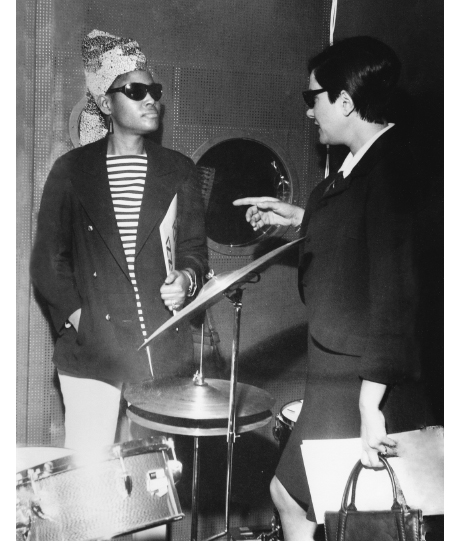

Milano, 1967—“No, I'm not a soul sister, but I am a sister of the soul.”

Photographer unknown

Milano, 1967—His personal Italian/English interpreter through the years.

Telegram from New York to Rome, 1968, addressed to Francesco, age eight, on the day of his First Communion.

Abbey and Francesco in Rome, 1981.

Max Roach on Dizzy's Day, Bassano del Grappa, 1987.