JOHN BIRKS “DIZZY” GILLESPIE

The Joyous Soul of Jazz

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

This story is not about Dizzy Gillespie seen as the world-famous artist, the musical innovator, the composer and arranger who led the way to new, daring, harmonic and rhythmic inventions. Nor need we refer to the amazing instrumental performer.

We shall not dissert on his historic importance, nor will it be a biography, there being an excellent To Be or Not to Bop translated into many languages. Dealing mainly with his adventures in Europe, you could consider this an addition to that biography, which does not mention his longstanding relationship with Italy.

It could also be useful to the “lay” reader interested in the general world of music thus discovering a stimulating, unusual personality, a hero of the Afro-American culture for which the United States is admired and appreciated the world over.

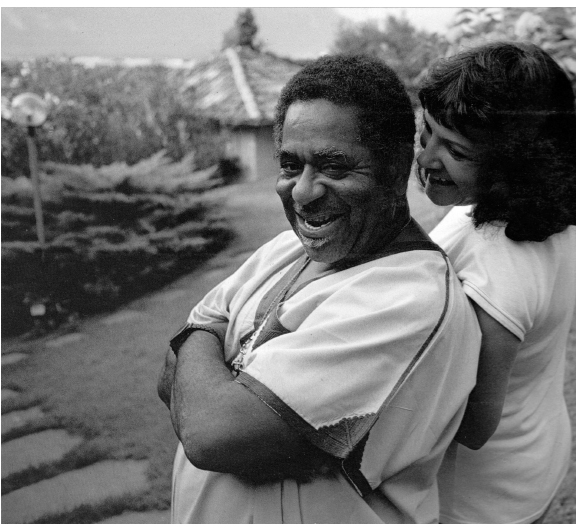

You might consider this book a “bedside” companion, aimed at giving you a different insight on the private, humorous, and thoughtful human being that was John Birks Gillespie as we knew him.

ACT I—TO BEGIN

Having an exuberant, multifaceted personality, Dizzy Gillespie has no doubt amused, amazed, annoyed, angered, and perhaps scandalized people with his irreverent “so what?” and “why not?” attitude. In an interview he had explained that, living as a black boy in the Deep South, therefore in a dangerous world, he had trained himself to face any harmful problems from early childhood. In fact, for many years he had carried a pocket knife to defend himself from the attacks of drunken rednecks on a “Saturday night nigger spree.” He still had a vivid recollection of the horrible death of his friend Bill, who had been tied down to the railway tracks and run over by a train.

“Good heavens, Dizzy! That must have shocked you for life! Was that what made you so aggressive?”

“Heck no! I spent all my childhood getting into mischief. I was small and skinny but real fast and real mad. In the end, even the big boys would stop heckling me and steer away.”

“And at home?”

“Well, I was the youngest, so my brothers and especially my sister were really pushy with me.” His big laugh: “In fact, one day Eugenia really pushed me…out the window! Said I was too wild!”

Another facet of his irrepressible personality were his outspoken political ideas, albeit formulated with humor. Some might recall that in 1963 he had given election politics a shake when, tongue in cheek, he had presented his candidacy for president of the United States, running against Barry Goldwater. What had begun as a joke, with Ralph and Jean Gleason prompting the whole affair, was soon taken up all over California, where students wore “Dizzy Gillespie for President” buttons. From California the action spread out, reaching the media throughout the United States. It was obviously treated as a joke, and yet this “why not?” stunt may have contributed to open eyes—and eventually doors—with regard to future black statesmen.

A delicate matter had been his heavy drinking problem, which had developed in the 1960s and would eventually lead him to an emergency hospitalization. Once again, his wife, Lorraine, had taken him in hand, nursing him toward definitive recovery. However, concerning drugs and other addictions that were rampant, especially in the jazz milieu, he was firm and adamant on the mortal harm that could ensue.

It should be added that through those many years when Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were creating a musical revolution that would change the sound of jazz forever, his strong bond with Charlie made Dizzy watch over him to the day Bird died. He not only disapproved of and fought Bird's addictions—which would lead him to a tragic end in 1955 at age thirty-four—but he stood by him with enduring devotion.

He also took in hand, with a committee of other artists, the harrowing decisions and actions needed to extract Bird's body from the Bellevue morgue, to be sent to his mother, and to be buried decently in Kansas City. Dizzy said that Norman Granz paid practically all the bills.

Through the years, especially during the difficult problems Dizzy had to face because of Parker's hectic behavior, the press would try to obtain from him some negative comment regarding Bird, but Dizzy would smile, sphinxlike, and enunciate clearly: “My association with Charlie Parker is far above anything else I have ever done musically. He gives me tremendous inspiration, always and at all times.”

After Parker's passing away he declared: “It is said that our Creator chooses great artists. There is no other explanation for the fact that an artist like Charlie Parker had so much talent other than he was divinely inspired.”

And he would conclude: “Charlie Parker was the other side of my heartbeat.”

Dizzy Gillespie was a mixture of wiliness and ancient wisdom mingled with a juvenile naiveté. His flamboyant personality is probably foremost in the memory of the general public. To this effect, one excuse he would offer to explain his tendency, sometimes, toward an explosive behavior, was the fact that, having been born on October 21, 1917, he was a child of the Russian Revolution, which had “exploded” then.

However, leaving all these well-known stories behind us, for you can find some of them as part of his official biography, with this chapter I wish to pay homage to the very special human being he matured into, during his later years. Consider it a collection of memories lived over a period of two decades. Perhaps, while reading, you will catch a shadow of his laughter, his joy of living, his sharp humor, and his husky-nasal voice, and feel as if he has never really left us.

ACT II—A TRUE ROMAN

In the mid-1960s in Italy I was dedicated to the diffusion of that “elite” music called jazz by presenting a weekly jazz radio program and working on national TV not only as a singer but also producing, presenting, and interviewing famous international jazz artists.

That afternoon I was to meet “the great Gillespie,” whose quintet was to perform in a TV special. In those years he was not the mellow, wise, and relaxed human being who would bloom later; he was peppery, wisecracking, electric, and devil-may-care. He had the reputation of being a most unexpected personality who might create problems with the straight-laced TV producers of those years.

We were very formally introduced, and he gave me the big eye. I began explaining how the program would unfold, but he kept leering one minute and frowning in mock concentration the next. Aware that he was not really listening, I stopped talking altogether.

He nodded, grinning.

“OK-OK. What did you say your name was?”

“Lilian. Lilian Terry”

“That's not Italian…”

“No. I'm British, born and raised in Egypt. However, my mother is Italian.”

“Bet she makes great minestrone, huh? I love minestrone!”*

I smiled and gathered up my courage to ask if he could possibly play one of his earlier tunes that held a special meaning for me, like a good-luck chant.

“It's the one that goes ‘Oo shoo-be-doo-be, oo, oo.’”

He shook his head—sorry, no. They had taken it off the book and now were playing newer tunes. At my disappointment he smiled: “But one day I'll play it for you…”

He wiggled his eyebrows in a mock leer and whispered loudly: “If you promise we'll sing it together…”**

We still had a few minutes before the show was to go on the air, live. Now, any friend of Dizzy's will tell you how risky his live appearance on any show could be, but, in my innocence, I asked him if we could work out some Qs and As so as to have a smooth interview.

“Oh yeah? Don't you like surprises? They're the spice of life!”

“I love surprises, but unfortunately they don't.” I pointed to our stage supervisor. “You see that gentleman in the grey suit? His job is to check that everything is according to RAI standards, including the dialogue, and they are very formal.”

Dizzy smiled, one finger to his chin and head bent coyly to one side:

“Oh, yeah? And just what would shake them up?”

My instinct rang a bell, so I answered breezily: “No problem. I'll begin by explaining your leading role in the birth of bebop, so the public is made aware of your importance in the history of jazz. There will follow a brief interview where you'll answer me in English and I'll translate into Italian.”

“Ah-ha! So you'll clean up any bad language…”

“Of course not!” I replied in a mock stern tone. “Because I'm certain you're going to be the perfect gentleman!”

He gave me an odd look: “Hey! For a second I thought I had Lorraine there! My wife. You sounded just like her.”

“I take that as a compliment. Ah, there we are, they're calling us onstage.”

Lights, OK. Cameras, ready. We roll at zero. Ten, nine, eight…. Rolling!

Standing next to him, in front of his musicians, I told the public how very lucky we were to have the great Gillespie play for us for the next twenty-five minutes. A brief, relaxed interview followed in English and Italian. Yes, he was indeed happy to be back in Rome. Matter of fact, he always looked forward to coming to Italy at least once a year. Such culture, all those art treasures…not to mention the delicious food! The cappuccino! Ah, yes, he had many friends in Rome, where he felt very much at home. In fact, he was learning new Italian words every day. Like the Roman slang compliments that the guys shouted at the girls on the street; very, very interesting…

My instinct again…so I beamed at the camera: “…but enough small talk now. It's time to enjoy the wonderful music of the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet.”

Turning to him, I motioned: “Maestro? It's all yours! Prego…”

He watched me walk away, fiddling with the horn and grinning, then roared out with gusto his favorite, very brief if rather heavy, Roman compliment: “Aaaah Bonah!”

Such “compliment” could be translated approximately into “Rather appetizing!”

There was a sudden combined reaction. Simultaneously, I froze in my steps, the cameraman barked a laugh quickly smothered, while the inspector almost fell off his highchair. Satisfied, Dizzy flickered the pistons of his horn, counted off, and they exploded into “Birk's Works.”

I was not sacked that day, but it was some time before they would let me produce another TV special concerning any jazz artist.

At Newport

Two years later, in 1968, I was on my way to the Newport Jazz Festival to interview as many important jazz artists as I could approach, in order to produce a special radio series for RAI, the Italian National Network. Fortunately, I was driving up from New York with Max Roach and Papa Jo Jones in Max's blue convertible. He led me through the four days, from artist to artist, like a kindly guiding spirit.

Among the artists to be interviewed, Dizzy's name was underlined with a large question mark as I cringed at the thought of what might come out of his laughing loudmouth, but Max had said not to worry—come along and we might catch him in a thoughtful mood.

With my faithful tape recorder in hand I stood outside Dizzy's dressing room waiting, as agreed, for Max to call me in. It was unusually silent inside. Had I missed the appointment? Crossing my fingers, I knocked and peeked discreetly around the door.

Dizzy was there all right, with Max and other musicians standing or squatting around him and listening intently as he read in a very intimate voice from a book he held open in his lap. Max motioned for me to come in. This was a most unusual scene and a strange lecture from a man renowned for his aggressive good humor and unconventional behavior. It sounded like the teachings of the Gospel, the Koran, and the Old Testament sifted together. Very interesting, and for a fleeting instant I considered recording it, but, from the sober look on Dizzy's face as he read, I realized this was a very private moment, so I walked out on tiptoe, signaling to Max “later,” which he acknowledged with a nod.

Years later Dizzy explained that he had been reading from a book on the Bahá’í faith.

So there I was again in Dizzy's dressing room, introduced by Max as a good friend from Italy; a singer who wished to interview him for the Italian radio.

Dizzy, once again the hyper entertainer, immediately started reciting dramatically:

“Ah Roma! Cappuccino, tortellini, carbonara, calamari…. Say, how is Nunzio? You know my friend Nunzio?”

“Nunzio Rotondo? Yes, we've recorded an LP together with Romano Mussolini.”

“Ah yeah! Romano and that beautiful wife of his! Did you know she's Sophia Loren's sister? Lucky guy! And Loffredo, how is he? Say hullo to his mother for me. Tell her next time I come to Rome we'll take her to meet the Pope. You know she lives in Rome and has never met the Pope?!”

“Well, neither have 90 percent of the Romans…”

While talking, he kept eyeing me suspiciously, trying to trace me to some memory at the back of his mind; I just smiled at him.

The radio interview unfolded very pleasantly with the Gillespie verve, and he was obviously enjoying himself, trying to speak Italian in a message to all his Italian fans. A knock and a voice, announcing he was on next, brought the meeting to a close.

We parted with hugs and patting on the back. See you in Rome this autumn. Absolutely! Ciao! As I walked away from the dressing room, satisfied with the interview, he stuck his head out the door to call out: “Hey, wait a minute…! That walk…I remember you now…!”

His big laugh, then his yell: “Aaaah Bonah!”

ACT III—GETTING TOGETHER

By the mid-1970s, through various occasions to interview our artist, Dizzy and I would gradually discover points in common—similar reactions to particular happenings and those items that slip out in a conversation to enlighten you on the “other” side of the man: the simple human being, as opposed to “the entertaining star.”

A regular meeting would take place at the Jardin des Arènes at Cimiez during the historical and irreplaceable annual Grande Parade du Jazz in Nice, France. It was produced and organized by George Wein and Simone Ginibre, and every year I recorded various interviews for my Italian radio program.

My son Francesco, in his teens, was a budding piano student at the Rome Conservatory and totally mesmerized by Dizzy's brilliance. Throughout the festival days he would follow the Gillespie quartet from one stage to the next, noting diligently their tunes, absorbing each solo like blotting paper. On the long drive back to Rome he would give his blow-by-blow description of what eighteen-year-old Rodney Jones had played on his guitar; Mickey Rocker's fantastic drumming; the solid bass backing by Ben Brown; and how guest saxophonist Eddie Daniels would fit smoothly into Dizzy's phrasing. Not to mention the incredible repertoire with nuances of flamenco, as well as his famous Afro-Cuban of course…and a touch of funky…and even some rock! And what an entertainer! Concluding with: “He is sheer genius, he IS jazz!”

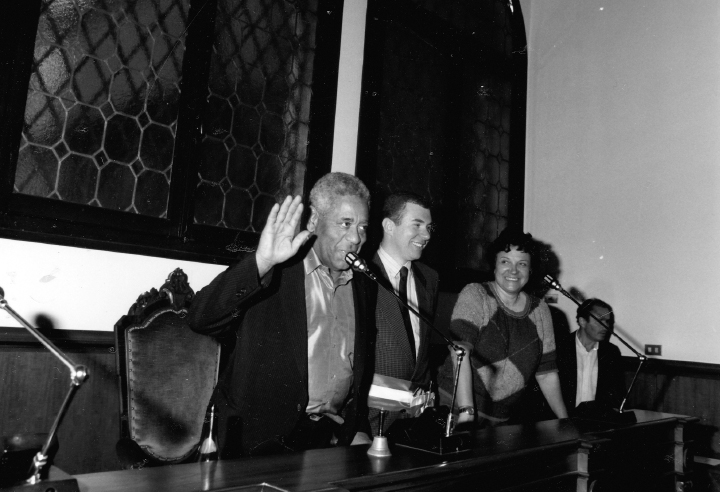

The turning point came when RAI accepted my proposal to produce a TV “Special Performance” with Dizzy Gillespie, who was to spend his day off, between concerts, in Rome. We had our theme: Gillespie in Rome. And what could be more Roman than the Coliseum?

The whole program was taped by the TV crew as it unfolded from his arrival at Fiumicino airport to his direct transfer to the Coliseum where, among a curious crowd, Dizzy went into his antics: a large cowboy hat perched on his head, humorous comments on the history of the place, all religiously recorded by the TV cameramen, as well as a crowd of Japanese tourists trailing behind with clicking and whirring cameras.

I was slightly alarmed at the thought of spending a whole day with this force of nature, when a small group of music students arrived and one of them presented Dizzy with a large color drawing representing him dressed in a Thousand-and-One-Nights costume, playing his periscopic trumpet from which emerged the Genie of Jazz. Dizzy was instantly interested and touched, and, giving all his attention to the young people, he listened patiently to their questions, which he would answer while the young artist translated both ways.

It was finally lunchtime, and Dizzy was informed that a jazz club had opened its kitchen to fix a special luncheon for him. The top Italian jazz critics had been invited along.

“You see, if they meet you when you are relaxed and nursing a contented stomach, they might discover a different Gillespie, not only the artist/clown you usually show onstage but the ‘other’ Giovanni Gillespo…”

He had been eyeing me in his shrewd way, miming a fake offense.

“The artist/clown? The other…what was it…Giovanni Gillespo? OK, I'll be Giovanni, but you'll be my interpreter and you'll translate exactly what I say, OK?”

And from that day on, throughout the many years, I was to act as his interpreter—and often regret it—translating not only his normal answers but also some of the most outrageous explanations he would give to that worn out question: “How did you get to play a twisted horn?” Most of his fellow musicians and friends have heard the different answers he would give, according to the pleasantness of the interviewer, but there were times when he would say such incredibly embarrassing things, expecting me to translate them faithfully, till I would give him the “Lorraine” glare and he would burst out laughing.

On that day at the Roman Jazz Club, he plunged into his special chicken dish with great gusto. The Italian critics, chatting and eating along, were enjoying this unusual press conference where he was truly relaxed and mellow. He was willing to listen to everybody and answer every question: personal, musical, religious, or political, and at one point our eyes met and he gave me a most benign smile, something of the wise Buddha. He nodded his approval of the “day in Rome” I had organized for him and, to punctuate his satisfaction, he offered us—journalists, fans, and complete TV crew with rolling cameras—a very discreet series of burps.

During another special moment that afternoon, Dizzy sat at the club piano with the young music students from the Coliseum crowding around him, most attentive and inquisitive. He would explain—illustrating his words on the piano—some of his solos on his famous records. The young artist who had translated for Dizzy at the Coliseum was right there with his questions, showing how deeply he had studied Gillespie so that later, stepping out of the club for a digestive stroll, Dizzy had pointed him out, expressing his surprise at the boy's knowledge of Dizzy's music.

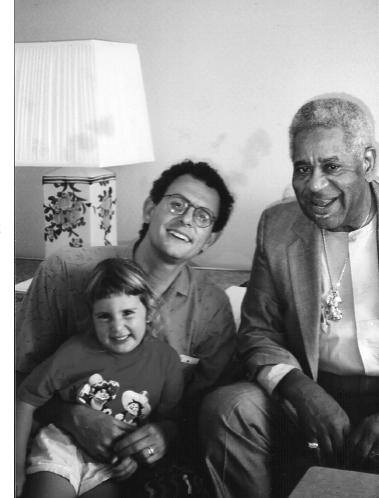

I had called the young man over: “Francesco…Dizzy is surprised at how well you know his repertoire…”

My son had grinned and replied: “Well, so I should, with all the festivals where I've been lucky enough to follow you around…thanks to mother…,” pointing at me.

Caught off guard, Dizzy's eyes had widened, and he had started the long “aaah…?” which turned into his famous rolling laugh; he grabbed each one of us by an arm as we strolled along.

From that Roman day onward there was a subtle change in Dizzy's attitude. The superficial benevolence he usually bestowed on everybody matured into a different behavior toward me. The “flirting” attitude gave way to a relaxed familiarity. It was as if we had always known each other, feeling at ease like old friends. When we commented on this “at ease” feeling he shared with my family—for also my mother had entered into the picture with her excellent “minestrone per Dizzy”—his amused explanation had been that we had probably all lived together in a previous life. He had opened his arms asking: “Why not?”

We had an open invitation to join him whenever he would appear in Italy, or at the annual Grande Parade in Nice, and during the long years that followed we established a firm relationship with “Giovanni Gillespo”; Dizzy had adopted the name immediately and through the years he would phone—sometimes at dawn—and roar his good humor: “Prontow? Buon-gee-ornow, this is Gee-iovanni, comee sta-eeh?!” and be delighted at my complaint for the ungodly hour. We would then gossip until he would say: “OK-OK, that's enough now. Go back to your beauty sleep…you sure need it! Hah! Hah!”

And he would ring off.

ACT IV—A RADIO INTERVIEW

In 1979 my “Portrait of the Artist” radio series presented—through interviews and special recordings—the most famous jazz personalities available. Evidently, Dizzy was included.

We began taping the interview after a satisfactory lunch and a brief “Jew's harp serenade” with our artist in a benign, reminiscent mood, as he sipped the cappuccino he favored.

“Tell me, Dizzy, just what is your secret?”

Raised eyebrows over the coffee cup and a surprised smile. I explained: “If I remember well, your very first bebop combo was organized in 1944, with Oscar Pettiford, to play at the Onyx Club on Fifty-Second Street, right? And who were the other members of the group?”

“Oh yeah. We had Don Byas on sax to begin with, then he was replaced by Budd Johnson. George Wallington on piano…but he was later replaced by Clyde Hart, and Max [Roach] on drums. But the real first combo was formed earlier, in December ’43 with Lester Young, Oscar Pettiford, Monk, and I.”

“However, the secret I want to discover is the following: If we listen today to your Verve recordings made in the forties and fifties, like ‘Groovin’ High’ or ‘Manteca,’ they are as fresh as if you had just recorded them. I mean, you belong to today's music even when you offer practically the same sound and repertoire you played back then. In other words, you can't be pinpointed to any particular era…”

“Well…the truth is that the ‘new’ style we created in the forties was itself directly developed from the ingredients and the atmosphere of the late thirties; and from that moment the evolution of our music, having those solid roots, simply developed right into the music that's played today.”

“Yes, but there's also the matter of your own very personal style…”

“As for my style…well, when you establish a certain style, you sort of stick to it, regardless of what you do. You try to resolve all the different possibilities, which are limitless in any given way. The style of the music I play is simply my way of playing. Whatever I'm playing, my phrasing will always be that way. If you are always cognizant of fundamentals, you hardly ever go wrong because you've got one foot in the past and one in the future. You're fundamentally the way that things have gone before.”

“Yet there's something particular about you. Many other excellent musicians who have remained true to their personality have experienced long ‘off’ moments with their public. You have never suffered from it.”

“I think another reason is that I'm also an entertainer, and I had good experience! I worked under some great entertainers such as Cab Calloway, Lucky Millinder, and Earl Hines, who is a real master showman! I watched them, and tried to find out why the public liked them rather than somebody else.”

“And what did you learn?”

“I discovered it's that personal touch, and the people know that I'm sincere, they detect it even if they don't know the language I'm speaking in. They can hear it in my voice and my demeanor, so that's another thing. There are lots of things you learn as you go along, you know? I am completely at the mercy of an audience. I know that it's my duty to reach them, not for them to reach me. An audience has no obligation; it stopped when they put their money in the box office. From that point on it's the obligation of the artist.”

“You mentioned Earl Hines. Some years ago he came to Rome to play at a jazz club called ‘Meo Patacca’ in Trastevere. During the radio interview, we got talking about his fantastic big band in 1942, with you, Bird, Sarah Vaughan, and all those other great artists. As we say: ‘la crème de la crème.’ He reminisced and spoke especially about you and Bird, how you would study together to develop your own special patterns that nobody else could figure out at that time. You were inventing together unusual things that you would then insert in the changes of the tunes, when playing in public.”

“Yeah…. We had like…a meeting of the minds, we were constantly inspiring each other. You could say I was more advanced harmonically but Bird was very advanced rhythmically. He was a great influence for all of us.”

“Going back to your way of reaching your audience: one fact on which all your fans will agree, no matter where you appear, is that while you do clown around on stage—don't frown, you know it is true…—yet the moment you count off and put your horn to your lips…”

“I know.” He grinned, “…I play my ass off.”

“Err…yes…. Now here's another question. Have you ever been curious, tried any of the new hybrid things that are being played nowadays?”

“Listen, I was doing that stuff they call rock-jazz or fusion music—whatever they call it now—way back. I mean, they're doing things now which we did in 1946, the same exact riff that we did then, so it's nothing new to me, nothing I hear from that angle that I haven't heard before, in some context. You could say I play that ‘new music’ too, because we've been doing it for a looong time!”

“Yes, but what you play has logic to it, while some of the things we hear today have very little to do with jazz as we know it. If we go all the way to free jazz: apart from Ornette, Paul Bley, and of course Mingus and his “free form” music, and a handful of others—what do you make of it? For instance, some of the electronic things that Miles Davis has been experimenting with recently…?”

“Well, I can't comment on what Miles Davis does because I wouldn't dare to take it upon myself to comment on an artist such as Miles.”

“That's exactly what is puzzling us. Because an artist of his stature, who has created a special world of music “à la Miles,” has no need to turn his back on it and look at the rock world for something…which he may not have found yet, or has he?”

Dizzy shook his head with a large grin: “Well, he's found a lot of money, I'll tell you that! Ha, ha, hah! So maybe that's what he was looking for? But seriously, you know? I've been trying to figure it out myself, and when I ask Miles, he kind of fences me off, saying, ‘You know what it is, ’cause you taught me.’ And all that kind of stuff.”

“But in your own opinion?”

“I figure that, perhaps, it's because at one time Miles had the perfect vehicle for his personality and his creativity, you know? He had Wynton Kelly, Jimmy Cobb, and Paul Chambers, but I don't think he's found that anymore, since then. Of course, at one time he had Red Garland and Philly Joe Jones; and that was something where he got off…”

“I know, and we can't forget the Kind of Blue period with Bill Evans! That's the Miles Davis I miss very much. Or those eerie heartbreaking sounds he gave us with Gil Evans?”

“Ah yes. But, you see, maybe right now, when he found that he can't find another Paul Chambers, or a Wynton Kelly—and they were just perfect for what he wanted then—well, maybe now he doesn't want to play any of that music without those guys…and he's got to wait until he gets to heaven to do so! You know, there must be some reason for him not wanting to play the way he used to.”

“I guess it's his right, even if I do wish he would surprise us romantics just once. Ah, well…I have another question for you. What's happening to jazz in the United States nowadays?”

“Oh, there's a big…but big upsurge in jazz now. I see a lot of young people in the public, and that's very good. And the new cats, they play real nice. You know, most of the time, in the past ten years, you used to look around and say, ‘Hey, I'm middle-aged, cause all my fans are middle-aged people,’ but now all the young kids are coming out, to play and to listen.”

“You're right. In fact, most of the young people in Italy are definitely your fans. And they are discovering Charlie Parker, Sonny Rollins, and John Coltrane, and also the fact that the music called bebop, which you guys invented in the forties, is a very basic moment in the history of jazz music, leading to what is being played today. But would you tell us more about yourself and Parker…?”

Once again, he was drawn back into his memories:

“Well…Yardbird and I just blended together from the moment he came to New York in 1942. They used to say we were like twins; our contribution just blended naturally. We were a great influence on each other's musical development, and in the way we played our notes, which were so close together. His enunciation of notes, the way he went from one to the other…that's what set the standard for phrasing our music.”

“In an interview, Miles said you and Bird played the same chords, played the lines together just like each other so he couldn't tell the difference. And Benny Carter explained that when you and Parker were playing those ‘other’ tunes within the original chords of the melody, the two of you were a natural irresistible association. He declared you simply turned the whole jazz picture around.”

“Well, like I said, Bird came to New York, to The Street, in 1942 and he sat in with us. That night I was hooked just by the way he assembled his notes together, and we sort of recognized ourselves in each other as colleagues and decided to play and exercise together every chance we got. By 1945 nobody played closer than we did; just listen to ‘Groovin’ High,’ ‘Shaw ’Nuff,’ and ‘Hot House.’ When Bird came in my life, he brought a totally new dimension on how to attack a tune and how to swing it. Our difference was that he had this ‘sanctified’ rhythm inside him. His accents had a definite bluesy feeling, while I got my accents from percussions. I guess we inspired each other with our differences.”

He grinned, remembering, and added: “But the real difference in our development was that I had to work constantly and hard, while Yardbird just grew into it naturally!”

“Just now you were saying that Bird played with a ‘sanctified’ rhythm?”

He grinned again and explained: “In Cheraw the blacks were divided into many levels of Christian churches. Starting from the top we had the Second Presbyterian Church, then the Methodist, the Catholic, the Peedee Baptist, and the A.M.E. Zion. The last and lowest was the Sanctified church where the whole congregation shouted. I would sneak in there, though I was raised a Methodist, and that's where I learned the meaning of rhythm and harmonies and how it could transport people spiritually.”

“Was that a ‘spontaneous combustion’ sort of thing?”

“Oh yes! There were four brothers in that church: one played the snare drum, another one the cymbal, another the bass drum, and the last one the tambourine. They had at least four different rhythms going on at the same time, and then the congregation would add the foot stomping and hand clapping, and jumping up and down on the resounding wooden floor. And the singing! It was just mind blowing. That's what I mean by ‘sanctified’ music.”

“What an experience that must have been! But what is happening now, jazz-wise?”

“You know, I honestly believe, actually I know that our music is conducive to what they are playing now. Our music and their rhythms…. In fact, I'm gonna make an album for the kids, to show them that our music is perfect for their kind of rhythm, because our music is really multi-rhythmic.”

“There's that record you made in 1977, with the ‘Shim Sham Shimmy’ and those other tunes that have the Gillespie imprint but are of easier reach, for those people who are not particularly jazz oriented.”

“Yeah…!” he smiled, reminiscing: “‘The shim sham shimmy on St. Louis Blues,’ that was fun!”

“Tell me, has this idea of a new record for kids just come to you?”

“No, actually I have already made one, not with my compositions but with Lalo Schifrin's. It's called ‘A Free Ride.’ Now I'm gonna try with my music, and it's really groovy.”

“We'll look forward to it. Well, I needn't ask you when you're coming back to Italy, as you are practically an Italian by now, especially with your ‘marranzano’ Jew's harp. So have you any special message for your Italian friends? Apart from ‘Ah bona!’ possibly…”

His wide grin: “Yeah! Ciao! Arrivederci Roma! Wait for me! I'll be back!”

ACT V—“TO BE OR NOT TO BOP”

I was acting as his interpreter at a press conference when Dizzy suddenly turned to me: “Do you also write translations…like…could you translate my book into Italian?”

“Yes, but do you have an Italian publisher?”

“Well, Doubleday tells me this Mondadori guy is interested…”

“It's not a ‘guy’ but the largest publishing firm in Italy. They're probably interested because Arrigo Polillo works with them.”

“Polillo!? We're friends from way back! So you think you could translate the book?”

“Well, I was interpreter-translator with FAO of the UN in Rome for seven years. And Ellington requested my translation for some articles for an Italian editor. But at Mondadori they surely have their own translators.”

“But would you like to do it for me?”

“Obviously. It would be interesting and amusing, I'm sure…. But you should let me have a copy of the book so I could tell you if I am up to it.”

“Here, write down your address and I'll have them send you a copy, and I'll tell them I want you on the job. I'll tell Polillo!”

Doubtfully, I complied. I was wrong to doubt, for in April 1980 our friend and jazz critic Arrigo Polillo had obtained Mondadori's decision to publish the book—even if Mondadori was not particularly interested in jazz—and the translating job for me, adding with a little laugh that he might not be doing me a favor, as I was given a firm request that of the 502 pages of the original story, plus about fifty more as selected discography, filmography, honors and awards, and index, there should remain—after a heartless slimming diet—only about three hundred pages, all items included. Otherwise, the cost of the actual printing would not be covered by the number of copies they were expecting to sell.

I wrote to Dizzy on April 22, 1980:

Dear Giovanni, I have this minute been informed by Mondadori that they have acquired the rights to publish To Be or Not to Bop in Italy, and I am to translate it. They are also asking me to render the book attractive to the non-jazz Italian reader as well. So here we start with two main problems we must solve, together.

First of all there is the enormous number of pages that Mondadori requests me to chop off here and there, as the book is too voluminous. We'll have to examine that together. Next, I must point out that although you speak at length of the many European countries where you played, naming various musicians, critics or whatever, you do not mention Italy or Italians at all. It would be very diplomatic if you were to add some Italian anecdotes. I am sure that interesting or funny or drastic things must have happened to you also in Italy. So please put down these paragraphs for me, as it would make the book more attractive for our Italian readers. Let me know how you wish to go about it. Meanwhile, I shall get on with the translation.

Now, a professional translator will understand my plight, as I had not only to translate from a black American jazz idiom into an Italian language “hip” enough to reflect Dizzy's personality; but I also had to choose where and how much to “slim it down” by a good 250 pages. Rolling up my mental sleeves, I opened the book with a dubious heart.

I was soon in total despair, and I called Dizzy and told him so. He asked me to give him a few days to talk to his co-author Al Fraser and they would come up with some advice.

Some time later I did receive a very pleasant and encouraging letter from Al Fraser, who wrote, among other things: “Dizzy and I have discussed the matter of foreign language editions, and because of his friendship with you, I am confident that you will complete an excellent translation.” He then gave me a few points of advice and encouraged me: “Feel relatively free to make small cuts where the book seems too repetitious or digresses too far from the narrative's thrust. Everything must be done to preserve the book's value as modern jazz history and points of disagreement between Dizzy and other narrators should be preserved at all costs. Every effort should be made to retain the spoken rather than the written quality of the narratives in order to convey the idioms and the rhythmic and poetic qualities of the jazz musician's speech.” More suggestions and advice and then a closing phrase: “I'm counting on your translation to help make To Be or Not to Bop the book Italian readers will dig with all their hearts and souls.”

Feeling relieved, I thanked him and Dizzy. However, I suggested that they also speak to the American editor, so Dizzy in turn spoke with Sandy Richardson of Doubleday in New York, with whom I subsequently spoke on the phone as well, and finally I was told to go ahead.

When I mentioned my worries Dizzy simply laughed, saying blithely, “Listen Lil, I trust you. So you just use your judgement.”

“It means I'll have to chop off here and there.”

“OK-OK!”

“I mean abundantly, lots.”

“OK-OK!”

“Well, fortunately you do have the habit of reiterating words more than once.”

“Oh, I do?”

“You do.”

“OK-OK, just follow your instinct, and do your best. Ciao Bonah!”

And he rang off. That was all the assistance he gave me.

It took me two excruciating years to translate the book into “soft” Italian slang, while chopping off a repetitious paragraph here and there. When the first draft went to the editors in Milano, they sent it back with compliments for my effort but asking for further slimming and to please make it a little more “good Italian,” as their readers were used to a different style of language…

Some time later I wrote to Dizzy:

The Italian editor invited me to lunch the other day, coming all the way from Milano to ask me to take the book in hand a second time and give it a further slimming diet, as it proved too bulky and expensive the way it is now. He explained once again that, should it cost more than what they expected to earn in sales, they wouldn't be able to publish it at all. I hope this does not cause a harmful delay in the publishing date. What with repeated printers’ strikes, strong attempts at “taking over” from another publisher, and various judicial haggles and all…. But, like we say in Egypt, it's ‘Maktoob’: Fate will have its course. So here we go again, Giovanni Cappuccino!”

I turned out a last, slimmer, “good Italian language” version, and Mondadori promptly paid me.

Epilogue

However, our troubles were not over, as, by then, Mondadori had become involved in a long financial/legal/political/judicial battle, and in time it changed owners. In the end the new owners decided to cross off about 40 percent of the manuscripts about to be published. Jazz not being essential to their cultural image—they had most of the famous Italian and foreign authors—I was informed that the book would not be published at all. Heartbroken for Dizzy, I asked if I could offer the book to another Italian editor, considering it was translated and ready for publication. The answer was a firm NO, they had already informed Doubleday and in fact they had sent the bulk of my manuscript to the shredder. If some other editor wished to start the whole business of approaching Doubleday…fine, but they would have no access to the translation I had produced.

I asked Polillo at Mondadori to inform Dizzy personally and officially, before calling him myself. We were both very disappointed, and I was particularly upset for him. However, in the end Dizzy, God bless his nature, was the one to console me.

ACT VI—THE MAGIC MIMIC

It was 1981 and he was appearing as “guest star” at the Pistoia Jazz Festival. Just as they were setting up the bandstand for his group, all at once, the skies had burst open like a gigantic water balloon. They had never seen anything like it. Huge drops fell like liquid hail-stones, drenching not only the large piazza, mounted into an amphitheater—with the public running for shelter in all directions—but also and especially the very large bandstand, drenching the sound and light equipment, and anything that could have been used for the concert.

The young organizers were dashing all over the place trying bravely to mop up a constant pouring, checking over and again the useless state of the stage, while their faces expressed their distress and helplessness to deal with the catastrophe.

Finally, they came to where Dizzy was sitting backstage, in a makeshift dressing room. They explained how, to their despair, the stage had been declared definitely out of use by the Fire Department. Dizzy, relaxed and benign, puffing on his Cuban cigar, looked out onto the stage, up at the skies, around at the public in hiding under the scaffolding, and then asked: “What if we don't use any electricity at all, will the Firemen give their OK?”

The two men looked at each other then at Dizzy as if he had gone mad.

“But…Maestro! It's a huge Piazza, how could we hold a concert without any amplification?”

Dizzy gave his amused wise smile and pronounced: “I have done so much…with so little…for so long…that now, I can do anything…with nothing at all!”

Uncomprehending, they stared at me for a translation. They listened, speechless. I added that if Dizzy was willing to try anyway, then perhaps they should hurry and issue the information before the public gave up and left the place. They nodded, galvanized, and went out to shout the news, asking the public up front to pass back the information:

“Dizzy Gillespie is going to play for us as soon as the rain stops!”

His musicians and his manager, Bobby Redcross, expressed their doubts and worries, but Dizzy just laughed, reassuring them.

It took half an hour for the rain to gradually turn into a light, sporadic drizzle.

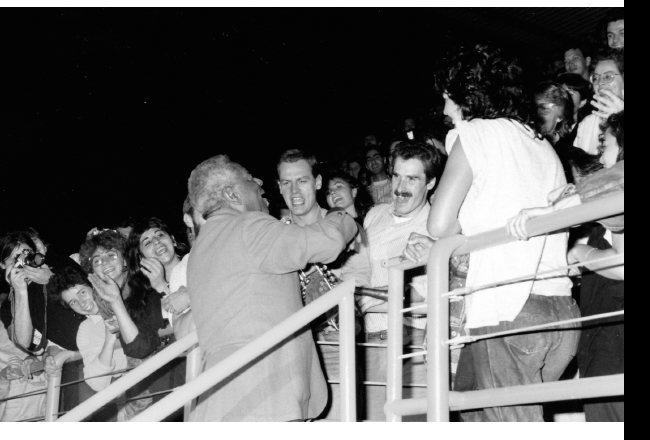

Unannounced, Dizzy stepped out with his musicians and, while the mopping and cleaning went on frantically behind him, he walked to the very edge of the high-perched stage and stood there, looking at the public and fiddling with his trumpet pistons. Eventually, more and more people noticed him standing there, till there was a roar of applause and they all rushed back to their wet seats, in excited disorder. Dizzy kept fingering his trumpet, looking around at the entire facility, and then made up his mind.

He bent down toward the large group of young fans standing, drenched, by the bandstand at his feet and motioned for them to hop right onto the stand, which they did immediately with enthusiasm. This produced a huge roar of protest from the public way back to the farthest rows, but Dizzy knew what he wanted.

He blew a long, high note then put his finger to his lips and went “Shhhhhhhhh…..”

Then he shouted out: “Hey back there…you hear me? Listen to me, you guys. Just listen to me!”

There were various cries of “Silenzio! Ascoltiamolo!” till the whole crowd was miraculously silent and expectant.

There followed a most efficient scene of mimicry. He pointed to the skies, looking up and bending sideways in biblical fear, and then put his hands in his hair, shaking his head in despair. He pointed to the various electronic instruments, lights and all, and then motioned to cut his throat, staggering. At this point the crowd was giggling but waiting earnestly for the rest of the improvisation. What would be the finale? He pointed to his temple. Idea! He pointed around at all the public, inviting the people to come down from the farthest seats and as close as possible.

By then a good size of the front crowd had settled right upon the bandstand at his invitation, till the Fire Department and the police had stopped any more ascents for safety reasons.

With practically all of his public as close as possible, and mimicking his words with his hands, in a most Italian style, he said loud and clear:

“OK-OK. Now if you guys, all of you—TUTTI—keep perfectly silent, SHHHH…we'll play for you and I promise you'll hear every note. So all you guys: SHHHH…We: MUSICA! OK? OK? OK?”

By then the whole audience was yelling OK.

Meanwhile the musicians had set up their instruments alongside him in a single line, close to the edge of the stand. There were young men and women all around them, delighted with this forced change of seating. At that moment the drizzle stopped falling altogether.

Dizzy looked up and, smiling, shouted his thanks to the heavens in his rough Cheraw-born voice: “GRRAZZIEH!”

Thus, on that magic summer night a huge, drenched, crowd practically held its breath and enjoyed a miraculous, totally acoustic concert as Dizzy counted off and they all went to spend “A Night in Tunisia.”

ACT VII—GILLESPO, ITALIAN STYLE

During the ongoing editorial struggle for the ownership of Mondadori, the final translation of To Be or Not to Bop had been approved, but there was still that lack of Italian anecdotes for the Italian version of his autobiography. Therefore, I had been requested to please grab the author during one of his tours and obtain the needed material from him. It would be inserted in the book as a special chapter, a bonus, for his Italian readers.

Joining him in his Roman hotel room I offered him a steaming cappuccino on condition that we tape a long chat about the Italian Gillespie. OK-OK.

“Giovanni Gillespo, you don't love Italy.”

“…Are you kidding? I feel at home in Italy, got lots of friends here. Lorraine loves Italy too.”

“Yet in your biography there is not one single line regarding your Italian memories. Think how your Italian friends will feel when they read the Italian version…”

“Hey, but…are you sure? There's no mention of Italy in the book?”

I shook my head and he went on.

“But I remember my very first time in Italy like it was yesterday! It was even before I came with Jazz at the Philharmonic. I remember arriving at the airport and there was this band waiting for me, with Nunzio Rotondo and Carlo Loffredo…”

“What year was this?”

“Oh, I'd say in 1951. That's when I became friends with Nunzio and Carlo. Did Nunzio ever learn to speak English after all?”

“I don't think so.”

“You know, it was really very funny the way we communicated. Neither one spoke the other's language so, while we were sitting together, Nunzio would suddenly jump up and rush to the nearest phone to call a girlfriend, who spoke English…no, I'm not kidding you. Anyway, he would tell her something in Italian on the phone, then pass me the receiver and this girl would say in English, ‘Nunzio wants to tell you that…’ (Dizzy started laughing), so I would answer her in English and pass the receiver back to Nunzio; I swear I'm not joking, that's exactly how it was. And, you know? This went on for years and years, always the same girl and always on the phone.”

“But why didn't you just bring her along with the two of you?”

“I don't know!? For years it went on this way. Nunzio would say something in Italian, shake his head…and off to the phone!”

“…with the two of you standing there, facing each other and not speaking directly? Madness!”

“Yes, yes! That's how it was! It was so funny…how we laughed! And then I remember the time we took Carlo Loffredo's mother to see the Pope. Think of it, to live in Rome and never have seen him! It was the Pope before Pope John, what was his name? He was a tall, thin guy.”

“Well, Pope Pius XII was tall and thin with a very ascetic face…”

“Yeah, that's the Pope we went to see…and she had never seen him before. We had lots of laughs that day, and then we all went to their home. Ah, Rome…”

“What other Italian cities do you know? Ever been to Venice?”

“Yeah, sure. That's the city with all that water…”

“Well, you might describe it so…”

Poor Venice, reduced to a “city with all that water.”

“Ah, and then Torino, Bergamo…. Wait, here's another funny story. I was coming from Paris to go to Bergamo and I was on this train by myself. I didn't know I was supposed to change trains in Milano so I just stood at the train window, looking around, and there was this guy with a beret that said ‘Interpreter.’ He asks me in English, ‘Do you need a hand?’”

“No, no, thanks, I'm OK.”

“And where are you off to?”

“To Bergamo.”

“What?! Bergamo? Jump off the train immediately if you have to go to Bergamo!”

And he helped me get off and change trains. You can guess how we laughed! I've often wondered where the hell I'd have ended up if I'd stayed on that train.”

“But with what band were you playing?”

“I think it was an Italian band because at the time I was on my own. Maybe with Romano Mussolini…must have been in the late fifties.”

“Very well. Now, if you think of Italy what is the first thing that comes to your mind?”

“Sophia Loren! Hah, hah!”

“Have you any unpleasant memories happening in Italy?”

“No, I really can't think of anything unpleasant relating to Italy. I recall when I came with my own band, and Lorraine was with me. We played in that theater in Milano…could be the Teatro Nuovo? Anyway, I remember I had lots of fun with the Italians when I'd find out they didn't speak English. I would tell them lots of strange words, totally invented, and they would laugh. Once when I was with the stagehands I asked one of them, ‘Hey, do you speak English?’ and he said, ‘No capish…. ’ The second one shook his head, the same with the third guy. So, looking bewildered at them, while they were laughing, I started exclaiming ‘What? You mean none of you guys speaks a word of English?’ and we went on like this, joking with my fake indignation, till Lorraine came to the door of my dressing room and told me, with that unmistakable voice of the wife who tells you off…she just said, ‘Dizzy?!’ And then you bet the stagehands understood English! They laughed like crazy! Just the tone of her voice was enough to straighten me up!”

“You said Lorraine enjoyed Italy?”

“She likes Italy very much. We were staying at the Hotel Duomo, nice place…”

“Tell me about the Italian public; have you always been happy with it?”

“Well, you know, Italians are a very particular people. Just think of the concert the other night when the rain ruined everything. I invited them to join me on the stage and it all went well, what more do you want? I don't know, I feel really at home among Italian people. It's as if I knew each one of them; there's a spontaneous link that's created between us.”

“So you had no particular problems in Italy?”

“No…ah, but yes! Wait, you've gotta hear this. I was part of Jazz at the Philharmonic, and we were playing this theater in Rome. Stan Getz was playing, and I was to close the show. Stan gets a big hand of applause and, as the time is almost over, Norman Granz motions to Stan ‘OK, that's it. Dizzy, get ready, you're on next…’ and he walks out on stage to announce me with a long spiel in English. The public—maybe because they didn't like him—starts throwing coins at him. My god, did Norman get mad! ‘That's it!’ he said. ‘Nothing more!’ But I hadn't played yet, and the public was ready to tear down the theater, so I said to him, ‘Hey Norman, I haven't played at all!’ ‘Damn! Well, go ahead and play just one number and then, no more!’ So I went out, played my tune, got a lot of applause, and then withdrew backstage. Well, do you know that, to make a long story short, they had to call in the police to protect us? We stayed in that theater for over three hours, with a mad public waiting for us outside!”

“Yes but, as you said, it was because of Norman's special way of coming onstage with his raised eyebrows, talking endlessly in English when the public wanted to hear the musicians, not him!”

“Yeah…ah, Rome…I remember one night, maybe the same of that concert, when we went on the Via Veneto to Bricktop's. It was very nice. Via Veneto was really beautiful then…”

“Did you take part in the Italian ‘Dolce Vita’ of those times?”

“The what?”

“The ‘Dolce Vita,’ you know…the famous film by Federico Fellini, with private parties, sexy girls…”

“Hell no. All I saw of Italy was a row of hotels and theaters. Ah, yes, and I saw the Pope!”

“Do you notice any difference between today's public and the old one?”

“Well, yes. They are all very young today. And at that time, in the fifties, the Italian public was more oriented toward traditional jazz rather than avant-garde. I mean not like in Sweden, or Denmark, where bebop was really at home even then. Italy was definitely more for traditional jazz.”

“But today you see many young people who do love bebop very much.”

“You're right, and I'm very glad. After all, it's like the music is going round and round; sooner or later you've got to get back to bop. Yes…the Italian public is really very warm—look at the other night, how disappointed they were when the sound equipment had gone for good, because of the storm. I got them to climb onstage and they were very cool. Actually, it was Bobby Redcross and the other guys who were nervous and scared. It didn't matter if once in a while some guy would get up to stretch his legs or smoke a joint…”

“Ah, by the way; that evening they offered you something…when you bent down toward the public on the edge of the stage, right?”

“Right! A big pipe full of hash! I was wondering what it was and that guy just offered it to me. I smelled it and gave it back…hell, it was hash!”

“I thought so. Unfortunately, in Italy we have a big problem with the heavy drugs. Many kids lose their lives.”

“It's what happens in the States, you know? Over there if some guy has an urgent need of a dose, and if he's very sick, he could even harm his own mother just to get it.”

“And what's the solution?”

“Perhaps if they could obtain it without harming anyone else…maybe helped by the State itself…who would then take them in hand to help them get cleaned up. Well, if after that you really want to kill yourself, then that's your own business. But I'll tell you something. There's too much money involved in the drug business. And every time there's too many dollars involved, you can be sure of one thing. They'll look for every possible way to fight it, except the right one.”

“You're right. But let's talk of something lighter—some other memory, some other name?”

“Romano Mussolini. I was very impressed when we first met, especially because he was the son of Benito, obviously. And do you know he invited me to his wedding, with the sister of Sophia Loren? I believe she was a singer too. Are they still married?”

“With Maria? Unfortunately not. I like Maria very much; she's a very sweet young woman and did sing rather well. But I'm not sure she really tried for a career.”

“Ah, I have another memory, when I think about Italy…the food!”

“I'd never have guessed…”

“I tell you, I discovered that in Italy they love to watch you eat and enjoy your food, and that's beautiful. There's that restaurant in Bologna…can't think of the name now but, I'm telling you, the food is really fabulous there. Now, you know that we usually eat whenever it's possible. It can be two in the morning or four in the afternoon, depending on the gig. So we were in Bologna to play a concert and then off again, and it was six in the afternoon. So I rush out of the hotel, get to the famous place…and it's not open yet. Closed to the public! Very disappointed, but, seeing some people moving inside, I start knocking and calling till they come to the door. I explain that I can't wait for the evening but if I cannot eat at their place I cannot say I have tasted a real meal in Bologna, worthy of its name. Anyway, the owner comes to the door, unlocks it, and invites me in. He leads me to the kitchen where they are just setting up the fires and he asks me what I would like to eat. Well, do you know that those wonderful people cooked just for me? And served me this marvelous meal in the main dining room, where I reigned all by myself? Ah, what a lovely memory I have of those people! It's something that could only have happened in Italy. Certainly not in New York! In Italy they have human warmth; Italians have a heart. If they see you have a problem, they will help you in any possible way. Give you anything you need. While in some other countries you can be sure they will help “remove” from you any possible thing. Oh yes, when I come to Italy it warms my heart. I am really sorry I did not mention Italy in my book, but it's not for lack of affection, it's more because my memory, my souvenirs, need to be held up by the memories of my friends. You know, I spend my life flying from one place to another, and in the end I have a hard time remembering.”

“It's understandable. Now, have you ever been to Sicily?”

“Sure! That's where I got my collection of ‘Jew's harps.’ Do you know I used to play it as a kid? But when I listened to those Sicilian harps…wow! Boy, they were perfection, not like the American ones. So I got myself a whole box in Palermo, but now I have only four left. I've got to return to Sicily to get another box.”

“The proper name in Italy is not Jew's harp but Marranzano.”

“M-a-r-a-n-z-a-n-o?”

“Right, except it has two r's.”

“Marranzano…I remember when I saw them in that little shop…and when I tried them…I said to myself ‘Ah-ha! This is something else; this is the sound I need…’ I think I'll make a whole record with the…marranzano…what do you think?”

“It would be very…interesting! But tell me, how come you played a Sicilian instrument while living in the Deep South? Have you ever lived near an Italian community?”

“Yes, but not as a kid. About fifteen years ago we lived in Corona, in New York State, where also Louis Armstrong used to live. I remember this little Italian shoemaker, on my street, with whom I had become friends. Every time I came home from my tours I would go look him up, sooner or later, and have a talk. Yeah, he hadn't the slightest idea of who I was. To him I was just a neighbor with whom to share a bottle of wine, homemade by him. And he would fix my shoes with his magic hands. One day I tell him I'm going to Europe and what would he like me to bring him back? ‘A Borsalino hat!’ When I got back to the States I gave it to him, but I would not take his money; we were just good friends. Anyway, one day I come home from a tour and find his shop is closed. So I ask his neighbor at the candy store: ‘Where's Frank?’”

“‘He has a bad heart, so he's shut his shop and gone to live with his daughter in the Bronx. Here's her phone number.’ So I call her: ‘Is Frank there, please?’”

“Yes, can I ask who is calling?”

“Dizzy Gillespie.”

“She drops the receiver, amazed, and I hear her asking her father, ‘What? You know Dizzy Gillespie?’ He comes to the phone: ‘Who's this? Dizzy who?’ I explain to him who I am and in the end he says, ‘Ah, sure! Gillespie, my next door neighbor…. So you are…YOU?’ How we laughed! He'd never had any idea of who I was; we were simply good neighbors. Great old man. He was Sicilian.”

“And when is it that you and Lorraine will come to Italy, simply as a couple of tourists?”

“Well…not as long as I'm playing…but I'll tell you something. I've bought a piece of land with Kenny Clarke on the French Riviera, and that's where Lorraine and I want to end up staying. It's close enough for us to come to Italy, visit our friends, and eat the food.”

“But you still don't speak either French or Italian?”

“Ah, but do you know the first word I learned in Italy, over thirty years ago…?”

“Is it something to do with food?”

“No, no. There were all these beautiful Italian girls who had me jump out of the car window, so guess what words my Italian friends taught me…to shout at the girls in Rome…?”

Remembering our first TV meeting I mock-frowned at him, to his delight.

“Yeah! Bbona! Hah, hah…Aah Bbbooonaaah!”

The interview ended there.

ACT VIII—CUBANO!

Dizzy enjoyed traveling using the Venice airport. Driving there in time for us to sit down in the comfortable waiting section and sip one last “outgoing cappuccino” plus cigar, we would comment on the past events and the next meeting to come. This time I commented on his headgear, which was, as always, very particular.

“By the way, Giovanni; you have the widest variety of hats, caps, berets, African headdresses, et cetera—now where on earth did you get THAT cap? It looks just like the one Fidel Castro wears!”

He gave me an amused, clever, little smile and then an offhand reply: “Well, yes. Fidel gave me this cap himself, in exchange for my cowboy hat…”

“Sure. And that's one of his personal Cuban cigars you're smoking, of course?”

A long side-look at me, then he carefully drew some snapshots from his wallet and handed them to me, in silence. There they were, grinning and pointing at each other, each with a fat cigar in his hand. Fidel was wearing a Stetson and Dizzy donning the famous cap. He then handed me a cigar with a gold band, where I read “Dizzy,” very briefly, for he put it jealously away in the special humidor portable case. Always silent, he puffed on his cigar with a satisfied smile.

“But how did you manage to get permission from the U.S. government to go to Cuba at all? I thought it was strictly forbidden for U.S. citizens to go there?”

“Right; but I've been going every year, invited by the Cuban Jazz Festival authorities, and by Castro himself. No problem.”

“No, really now…wasn't there a total embargo to visit Cuba? I mean…”

He interrupted me, and for the first time I saw a very sober man.

“Sure there was, and they tried to stop me the first time. But I told the State Department that if Eisenhower had chosen me—and used me—in 1956, as the first jazz musician to lead an orchestra to go on goodwill tours in countries where America was not too popular…”

“You mean the famous State Department Cultural Mission all over the world?”

“That's right; we were to represent the ‘democratic spirit’ with a racially mixed big band. They sent us to Africa, the Near East, Middle East and Asia, including India…”

“And you were the very first artist to be chosen?”

“Right, it was Adam Powell in Washington who convinced Eisenhower that we could smooth things out through our music, if we played for the very crowds who were protesting and throwing stones at our embassies all over the world.”

“And you did? I mean…smooth things out?”

“You bet, though at times it was scary…but mostly because they would have us play in the embassies or other U.S.-controlled venues, and the public would be made up of chosen guests while the little people were protesting outside. It was also because the organizers were selling tickets that were much too expensive. So you know what I did, in Karachi? I got a huge bunch of tickets from the impresario and just went outside and gave them away! And whenever possible we would go out to the parks, the markets, wherever, and we joked and started playing for the people, and it worked fine. We went to Persia, Lebanon, Syria, Pakistan, Turkey, and Greece.”

“And did you hold press conferences, debates on jazz history, or talk about the American way of life?”

“They had Marshall Stearns for that. He lectured on jazz in the various schools and colleges. As for the American way of life….” He shook in his silent laugh and nudged me: “You want to know? The State Department was worried as hell about my ‘unpredictable’ behavior, so they kept asking me to go to Washington, before the tour, in order to ‘brief me.’ But I was already on tour in Europe, so they got hold of Lorraine, asking her to convince me to come back for a few days. I told Lorraine to inform them I needed no briefing. I knew all about the American way of life and what it's done to us for hundreds of years! So if anyone asked me particular questions, I would give them an honest answer.”

“However, I know the results were highly appreciated by Eisenhower. You were given a special plaque at a special dinner at the White House, weren't you?”

This time he laughed outright. “Yeah, and some of the guys still kid me. About when the President started giving around these plaques calling each one by name. I was away from the stand so I didn't hear him at first till he called my name real loud, so I went forward waving to him and calling out: ‘Right over here, Pops!’”

“You didn't! Pops?!”

“Well, he didn't mind ’cause that was the start of a whole series of tours for the State Department; in fact we went to South America soon after.”

“Was that when you went to Cuba for the first time?”

“No, Cuba was something else. I had always wanted to go there. I think Cuba became special to me because of Chano Pozo. He made me discover a whole new rhythmical world right there in New York. He knew nothing about jazz; he was really African with his congas, and he got us all standing there like dumb kids, watching and listening to him play. He taught us what multi-rhythm was all about with those Cuban chants, each one from a different African root. I learned about the Nañigo, the Santo, the Ararra, and that's when I learned to play the congas. Chano taught me. He didn't speak English, he didn't know anything about jazz rhythm, but he taught all of us, starting with Gil Fuller, when we all worked on ‘Manteca.’ And Chano worked also with George Russell for ‘Cubana Be—Cubana Bop.’ It was really magic; it was the birth of Afro-Cuban Jazz.”

“But then what happened? Suddenly there was no Chano Pozo anymore?”

“Well, one day Chano went back to Cuba ‘for some business,’ he said. Seems he was involved in bad stuff with the wrong people. When he came back to New York, he got shot to death. It was a great loss for our music. In fact, I would like to be able to open a school in Cuba as a living monument to him.”

“But you still haven't told me how you got permission to break the embargo rules?”

“Well…I told the guys in Washington that after all those Cultural Diplomatic tours for the State Department for all those years…after that service, the least they could do was give me a free exit and entry visa back to the U.S. from anywhere in the world! So they did, and after that I've been going to Cuba whenever possible.”

“Good for you! It must be great to play in Cuba with all those musicians who look up to you from the time of Chano Pozo. I organized a concert last month with Arturo Sandoval and his incredible musicians, and there's no doubt as to who inspires him!”

“Arturo plays great trumpet. In fact, I've obtained for him to come and visit me in the States and play with me. And if I can, I'll get him a green card. He deserves it, and I'd love to have him in a future big band.”

“Tell me: of the young emerging musicians in Cuba, who would you say impressed you the most?”

“Ah, I know! There's this very young cat playing piano…Gonzalo Rubalcaba. You keep his name in mind, he's sure to emerge worldwide.”

“Gonzalo Rubalcaba. OK, noted.”

An announcement brought our conversation to an end.

“Ah, there we are, they're calling your flight. Give my love to Lorraine. I'll send you the clippings soon as I have them all in hand.”

We exchanged a hug as I continued: “So your Italian barber can read them to you…or you to him…you're practically an Italian by now…”

ACT IX—ANOTHER RADIO INTERVIEW

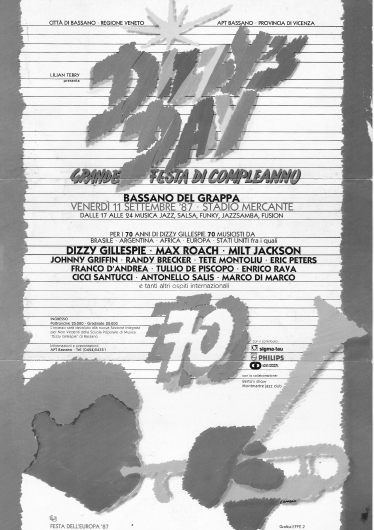

In 1982 Dizzy discovered Italian soccer through my son's enthusiasm for the Italian “Squadra Azzurra” and Paolo Rossi. It took place during the Jazz Festival at Lido degli Estensi, near Ravenna, on the very day of the Spanish World Cup finals, when Italy was to face Western Germany.

I spoke to Dizzy about the famous Italian football coach, Enzo Bearzot, a great jazz fan who tried to train the national football team to play together with the same “feeling” that links together a jazz band. He had also confessed to sneaking away to New York every year to “fill up with lots of good jazz.”

Out of curiosity, Dizzy settled himself next to Francesco in the crowded hotel TV room, among the other excited fans, and before long he was caught up in the general enthusiasm and was rooting for Italy. To their great satisfaction Italy beat Germany 3 to 1, winning the World Cup.

In Ravenna I proposed a radio interview, and Dizzy accepted willingly. With a cappuccino warming his hands, we were off:

“Apart from your music, which other things really interest you? I mean, what do you do with your free time?”

“Well, I sleep a lot…sure, go ahead and smile; however, I've got fresh news for you. Maybe you don't know this, but they are building a Dizzy Gillespie Center, for the cost of two and a half million dollars…”

“And where is this taking place?”

“In Laurinburg, South Carolina.”

“Wasn't that your old school?”

“Yeah, that's where I studied as a kid—and listen to the idea that they worked out in order to collect the money. It's rather original, I would say unique. It will be a Center for the Arts, Communication, and Teaching. With a theater and a permanent library that will gather all my papers and documents. Then there'll be a gallery of famous names.”

“What about the money?”

“Wait now. Right on the front of the building they'll put a small bust of myself, placed right on top of a wall of bricks, and every single brick will have a number carved on it and inside the building there'll be a panel with the corresponding number and the name of anyone who wishes to become a founding associate…It will cost five thousand dollars for each brick.”

“And you've already started gathering members?”

“Norman Granz was the first one and George Wein; then Quincy Jones, Lionel Hampton, Morris Levy, which makes five. Then Oscar Cohen of ABC Associated Agency, Willard Alexander…”

“Apart from Quincy and Lionel, they are mostly promoters, organizers, and agents, aren't they?”

“Yeah, and it won't be difficult to sell those bricks because I know I have that kind of friends with that kind of money. Another thing, always inside, for those who have less bread, like me, there will be bricks for twenty-five dollars…and everything will be computerized with an information center. You'll press a button and have your answer.”

“And what'll be the objective of such an institute?”

“Well, when it's completed, all my friends will want to give part of their time to teach there.”

“Now that's a beautiful idea; have you already started construction?”

“No, not yet; right now we are simply putting the money together.”

“It will take a few years then…?”

“Yeah, but I'll be hanging around, keeping busy. I'm not going anywhere else.”

“What about your plan to retire to the south of France and build a house next to Klook?”

“Well, right now I have the land next to him; all I need is the money to build the house…and that will take some four or five more years, I think. Lorraine likes the idea; she likes France.”

“Let's talk about Lorraine. There's always a great woman behind a great man, they say. And from your autobiography I get the impression that she has always been your backbone, providing the firm ground on which you've been able to skip and hop at will.”

“Lorraine is the anchor and I am the sail…”

“And how long has it been since she last came abroad with you? I get the impression that she would rather stay home and enjoy the house, the privacy. But you, being always on tour…how much time would you say you spend at home?”

“Not enough, but next year I intend to shorten my activity.”

“And what will you do?”

“I'll enjoy my house. I'll have lots of things to do.”

“Talking of things to do…it's been a long time since you've composed any new music or written those arrangements for which you are famous. I mean, after all, there is a whole Dizzy Gillespie world of music. Why did you stop? Too lazy?”

“Well, that's one of the reasons, I guess, my laziness. But I do have something special in mind. You see, as you know, I belong to the Bahá’í faith, which preaches unity in all the aspects of the Universe. Unity in diversity. And this includes music. Well, in the music of the Western Hemisphere, the one I know best…and I'm talking of Cuba, Brazil, the West Indies, and the United States…this music has its own unity, and I mean to put it together in such a way that when it will be played, you won't be able to say this is Cuban and this is something else. Music has only one mother…and that's what I'll work on, during my free time…. Like a United Nations band.”

“Have you started working on it, or is it just an intention?”

“Well, I know exactly what to do; all I need now is the time to do it.”

“Tell us a little more about Lorraine.”

“Lorraine is probably the most incorruptible person on the face of earth. For her there are only two solutions to a problem: the right one and the wrong one. There are no halfway solutions for her, and at times this is a positive fact…but at times it isn't.”

A small wry smile as he goes on: “I'm not saying she has the answer to all the problems of humanity, but she's the one who comes closest to the solution of many human problems. You know what would be her favorite pastime? Honest? Her greatest joy would be to be a real multimillionaire…and then give away all her money in the best way according to her ideas. That's what she would like. She never wants anything for herself, nothing at all; she's extraordinary, you know? After over forty-one years of marriage—we celebrated our anniversary on May 9th…”

“And were you together for the occasion?”

“No, I was on tour…but she and I know that some things have to be done, there's no problem…”

“Did you get her an adequate present?”

“No, but I'll tell you…I was waiting to come here, close to the Vatican to get her something special. Maybe you could help me. She's a very fervent Catholic as you know…and I thought I might perhaps find something that Christ used to carry around in His pockets…”

I gave a gasp, then burst out laughing “Oh, Diz, come on!”

“Yes, yes, don't laugh…that would really be something…”

“Yes, something special and most uncommon and very precious, I'm sure! But I hardly think they would sell it, even if such an item existed…”

“You think He had no pockets?”

“If He did, whatever He was ‘carrying around’ in them would not be for sale!”

“Yeah…I guess not…,” he smiled wryly “Well, then I'll have to get her a gift really worthy of her. It's no good just going to a jeweler and bringing her a piece of jewelry…”

“No, I guess it would have to be something very special and personal.”

“Once I brought her a rosary made up of gold pearls, eighteen-karat gold and every pearl had a different sculpture…. It was really a wonderful object.”

“Is Lorraine a very religious woman?”

“Ah, yessir! She is Catholic and very active.”

“And what does she think of the fact that you are Bahá’í?”

“She doesn't understand it, but she respects me and recognizes that each one must make his own decision regarding his relationship with God.”

“By the way, you and Lorraine have never had any children, right? Have you any other person…like some youngster, a nephew, someone you might have adopted sentimentally?”

“We have two of them, which we adopted. Today they are adults, and we help them financially. It's easy to help your family, Lorraine says, but you need a kind heart to help a stranger.”

“How very true. Now, let's get back to the Bahá’í philosophy. What attracted you to their doctrine?”

“It's the philosophy on the unity of human beings. Their teachings are based on the following theme: Humanity has gone through many generations, and three epochs have been fixed in the evolution of man. The first was the concept of Family, then came the linking of the Tribe, then came the Cities, the States, and the national Governments. All this was done. Now the next logical step is the unifying of all these various components, and this is the aim of the Bahá’í: a World Commonwealth where everybody would participate.”

“Yes, but isn't it just a very beautiful Utopia? How do you make it come about concretely?”

“With an administrative organization, like the one the Bahá’í already have. It would be enough for the rest of the world to refer to it. It had been hard to create the Family, and then it was difficult to put together the Tribe. As for the Nations, we are still making a mess of it today. But we can still obtain the final goal, with God's grace, because what will happen is this: With the fact that most nations have nuclear power, nobody seems to be afraid of his neighbor, and they wouldn't think twice of throwing an atom bomb. The United States have already done so since 1945. So there really is no other way to save ourselves but to have unity among the people of the world.”

“Yes, but how long will it take?”

“That's not what is important…”

“Maybe you and I will no longer be around?”

“Not necessarily—something could happen in the future that would force them all to reconsider…. The idea is to love humanity enough to realize this project. Whether you can directly participate or not is not what's important.”

“But then wouldn't it be a political action?”

“No, no! We Bahá’í are not authorized to move politically, but we must give these ideas to the people, get them to think about it. We do not have a clerical hierarchy, or preachers, et cetera…. We are all equal; our way of acting is through the contact person to person.”

“How many countries host Bahá’í groups?”

“There are about 200 countries in the world. [The Bahá’í] teach that all religions are really one. The difference is in the various epochs. There is the message Moses gave, then the one from Jesus and also the other religious leaders. The message is really the same. The difference is only in the social order, which goes with that one religion that is most appropriate for the times in which it appears. Each religion taught the best way to live in its time, and each time has its message.”

“But do you have a leader, like we have the Pope, for instance?”

“We've had a Guardian of the Faith; he was the nephew of the First Prophet, but he died in 1959 and is buried in London. He decided that there would be no other Guardian after him. He simply left us the instructions that were given by the First Prophet.”