This text of Paradise Lost is based on the second edition of 1674, the last edition published in Milton’s lifetime and the last over which he exerted some degree of control. The qualifier “some degree” is necessary because Renaissance publishers normally introduced their own habits of orthography and punctuation into printed texts. Milton, who is usually assumed to have resisted this practice more than other authors of the period, by no means had his own way in these matters, as we know from the fact that the Pierpont Morgan Library manuscript of Book I of Paradise Lost is more lightly punctuated than the printed version. We have assessed significant variations found in this manuscript, in the first edition of 1667, and in editions subsequent to 1674 on a case-by-case basis, and discussed them in our notes. The virtues of an eclectic approach to editing Milton have been ably set forth by John Creaser (1983, 1984).

We have sought to ease the journey of modern readers. Most of Milton’s capitalizations, italics, and contractions have been removed. Quotation marks came into vogue some years after the death of Milton, and they do not appear in the first two editions of his epic. We have added them. His spelling has been modernized and Americanized; “brigad” becomes “brigade,” and “vigour” becomes “vigor.” But there are important exceptions to these preferences. Our efforts at modernization have been checked by a desire to preserve whenever possible the sound, rhythm, and texture of the poem. We have therefore left archaic words and some original spellings intact; “enow” does not become “enough,” and “highth” does not become “height.” In cases where Milton’s contractions indicate that a syllable voiced in the modern pronunciation of a word is to be elided, as with “flow’ry” at 9.456 or “heav’nly” at 9.457, we have left them alone. Sometimes the final -ed in words such as “fixed” is not voiced, as in “Of Godhead fixed forever firm and sure” (7.586). Where -ed is a voiced syllable, as in “His fixèd seat” (3.669), we have placed an accent mark slanting down from left to right.

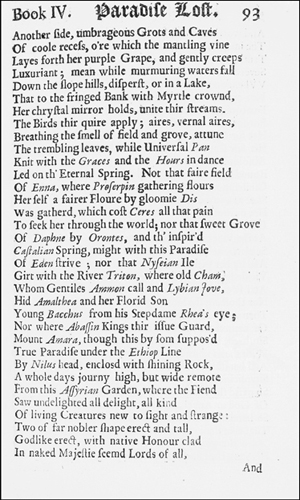

Book IV, lines 257 to 290, from the second edition of Paradise Lost (1674). (illustration credit fm4.1)

Punctuation offers especially complex choices for modernizers. For punctuation, or “pointing” as it was called in Milton’s day, serves two purposes at least. It displays the logic of the syntax, aiding a reader in the basic chore of construing sense. But especially in a poetic text, and more especially still in the poetic text of the seventeenth century, punctuation also indicates rhythmic pauses. It is generally assumed, perhaps without much evidence, that a semicolon points to a longer pause than a comma, a colon to a longer pause than a semicolon, and a period to the most pronounced pause of all. Milton’s punctuation is difficult to update for modern readers in both of its functions. For his syntax is not packaged in the modern unit of the sentence. The grammatical shoots of Paradise Lost twist and turn like wanton vines. His verbs can refer back to subjects introduced some ten or more lines before, and what seem at first to be subordinate clauses will often develop complex syntactical lives of their own. On the rhythmic side, many of the commas and semicolons that look superfluous by modern standards could well indicate the sound-patterns of his verse. Some readers would argue that, whenever the two functions of punctuation come into conflict, sound must be sacrificed to sense. But in poetry, as in good prose, sound-patterns are, above and beyond their inherent beauty, meaning-patterns. Countless works of criticism have demonstrated that sound effects in literary language have the power to bear meaning, and we see no reason to doubt these results. Milton, moreover, is widely judged to be a supreme master of this aspect of literary craftsmanship.

Given these concerns, we have sought within a general framework of modernization to respect the punctuation schemes developed by Milton and his publishers. We remove a number of commas. Some are changed to semicolons and periods for the sake of readability. But in places where marking the rhythm seems paramount (see 2.315), we reproduce either closely or exactly the pointing of 1674.