Chapter 2

After he got back from Centerboro Freddy spent the rest of the day and most of the evening getting the pigpen in order and putting out things to take with him in case he really did get the caretaker job. He made a big pile of these things, and then he went over them one by one, saying to himself: “Now, do I really need this, or shall I leave it here?” All this was a great waste of time, for he couldn’t make up his mind to do without any of the things, and the pile was just as big when he had gone over it as it had been when he started.

After that he made out a list. It looked like this:

THINGS TO DO BEFORE LEAVING

Cover up typewriter

See Mr. Bean

Give going-away party (?)

Close bank

Collect 10¢ Robert owes me

Get Mr. Bean’s permission

Show Weedly about being reporter

Lock window

Explain to Mr. Bean

The list was much longer, and writing it was a good deal of wasted time too, because he could have done many of the things in the time it took to write them down. But Freddy liked making lists of things. He had a feeling of satisfaction when he had written down something to do. It was almost as if he had really done it. And of course much less trouble.

He felt specially that way about getting Mr. Bean’s permission to go away. That is why he had it on his list eight times. Mr. Bean was very fond of all his animals, and proud of them too, and he very seldom refused them anything they wanted. But he had a very gruff way of speaking which made them always a little afraid of him. My private opinion is that his gruffness was all put on, to hide the affection he really felt for the animals. Or it may have been just the way his voice came out through his whiskers. He had a very bushy beard which concealed almost his entire face, and even the kindest voice coming through such whiskers might well get changed into something else. I guess you would sound pretty gruff if you had to say everything through what was almost a small haystack.

Freddy went on adding things to his list and going through his belongings until at last about eleven o’clock he decided to go to bed. “My goodness,” he said as he snapped out the light, “I suppose I might just as well sit up. I’m so excited that I shan’t sleep a wink!” He put his head down on the pillow and closed his eyes and sighed, and then he sighed again, but halfway through the third sigh it turned into a snore, and he didn’t know anything until Charles, the rooster, woke him up the next morning.

As soon as he put his nose outside the door he knew that it was going to be an even hotter day than yesterday, so after a hurried breakfast he started out to call on Mr. Camphor. It was nearly eight miles by road to Otesaraga Lake, but if you went up the brook and through the Bean woods, and then up through the Big Woods and over the hill, you came out in a wide valley. And if you crossed that valley and went over the next hill, there was the lake. That way it was only about three miles.

Freddy walked up along the brook. When he got to the duck pond, there were Jinx and Weedly, talking to Alice and Emma, the two ducks. Under a bush near them sat the ducks’ Uncle Wesley, with his head under his wing.

“Hello, Freddy,” said Jinx. “Weedly and I thought we’d take the day off and go up to the lake with you if you want us to.”

“Glad to have company,” said the pig. “What’s the matter with Uncle Wesley?” he asked. “Isn’t he going to get up this morning?” For it is unusual to see any animal or bird still sleeping after the rooster has crowed three times to get them all up.

“He isn’t asleep,” said Alice. “He’s just meditating.”

“About what?” Jinx asked.

“Oh, I don’t know. He says the things Emma and I talk about aren’t half as interesting as his own thoughts, and he sits that way so he can think and won’t have to listen to our chatter.”

“You mean he’s not listening to us now?” asked Weedly, looking curiously at the sleeping duck.

“I’m sure he doesn’t hear a thing we say,” said Alice.

“Oh, yeah?” said Jinx. He winked at Freddy, then said in a loud voice: “Well, that’s good, because there’s something I wanted to tell you that I didn’t want him to hear.” Then he lowered his voice and said very fast under his breath: “Umbly, umbly, umbly, umbly.”

And Uncle Wesley’s head popped out from under his wing.

“Ah!” he said. “Company! Good morning Jinx, Weedly. Good morning, Freddy, my boy. Were you saying something, Jinx?”

“No,” said the cat, pretending to look embarrassed. “No indeed, nothing important. Oh, no.”

“Come, come,” said the duck, waddling up to Jinx in his fussy pompous way, “no need to hide anything from Uncle Wesley. He can keep a secret, I imagine, as well as any of you, eh?”

“Well, if you really want to know what I was saying—” Jinx began, then paused.

“Yes, yes,” said Uncle Wesley impatiently.

“I said: umbly, umbly, umbly, umbly.”

Uncle Wesley puffed out his chest. “You said what?”

“Umbly, umbly, umbly, umbly,” repeated Jinx. Then he grinned, and the two pigs grinned, and even Alice and Emma tittered a little.

Uncle Wesley was no fool and he saw that the joke was on him. He was pretty grumpy about it at first, but when Freddy had assured him that they wouldn’t play jokes on him if they didn’t like him, and when Jinx had slapped him on the back and called him “Wes, old pal,” he stopped sulking and became much interested in Freddy’s proposed call on Mr. Camphor. “I’d like to go along with you,” he said, “but I guess it’s pretty far. My feet, you know.” He held up one yellow webbed foot for their inspection. “Aquatic sports, now; I’m your duck for that. But walking in the woods—no, no.”

“If I get the position,” said Freddy, “we’ll have a picnic some day, and Hank can bring you up and we’ll all go swimming in the lake.” Then he turned to Jinx. “Well, come on; let’s get started.”

They went on up the brook, and as they turned into the woods they looked back. Alice and Emma were swimming about peacefully, and Uncle Wesley, with his head under his wing, had returned to his meditations.

It was cool and damp in the woods; in many places it was so wet underfoot that the pigs splashed along ankle deep in water, and Jinx, who hated getting his feet wet, rode on Freddy’s back. Here and there patches of unmelted snow still remained in hollows and under sheltered banks. After they had passed out of the Bean woods and across the back road into the Big Woods, the ground was drier, and Jinx trotted along ahead looking for squirrels. He liked to tease squirrels. He seldom chased them, but would sit on the ground and make faces at them, and the squirrels, who are rather short-tempered animals, would get madder and madder, chattering and screaming and jumping up and down until they almost fell off the branches. It was lots of fun.

But Jinx didn’t see many squirrels in the Big Woods, for although the Ignormus had been exposed and defeated by Freddy and his friends, the animals were still a little fearful of the place where he had lived for so many years, and few of them cared to settle there. Even Freddy, remembering how scared he had been in the past among those big trees, hurried along a little faster, and he was glad when they were over the hill and came out into bright sunlight again on the farther slope.

They crossed the valley, climbed the long rise to the top of the next hill, and there before them stretched the blue waters of Otesaraga Lake, sparkling in the sun. And beside the lake stretched the green lawns of the Camphor estate, and they were almost as smooth as the water. Among the trees at the right they could see the roof of the big house.

Freddy stopped short. “My goodness,” he said, “do you suppose the caretaker would have to keep all that lawn mowed?” He turned around. “Come on, let’s go back.”

“Hey, what’s the matter with you, pig?” said Jinx. “You haven’t come all this way to be scared out by a little lawn mowing, have you? Best exercise in the world. And goodness knows, you need it!” he said, poking Freddy in the side.

“I don’t need it that much,” said Freddy. “Look at the size of the place! Why, if you started with a lawn mower at this end and went around, the grass would have grown six inches high before you got back to it.”

“Well, if you want to go home again, all right,” said the cat. “Be quite an honor to have charge of such a grand place. You’d be a pretty important person around here. But of course if you don’t think you’re good enough to tackle the job, there’s nothing more to say.”

“Oh, well,” said Freddy, “as long as we’re here, I suppose I might as well go down and find out what there is to it. I don’t have to take it if I don’t want to.”

“Certainly not!” said Jinx and Weedly together, and they winked at each other and followed Freddy down the hill.

Pretty soon they came to the high wall that surrounded the estate, and they followed this along till they found some iron gates. The gates were open and they went through them and up a long drive that wound in and out among trees and shrubbery until it came to the house. Freddy and Weedly hung back a little when they came in sight of the house, but Jinx went straight up the middle with his tail in the air as if he owned the place. But when they got to the front door he stood aside.

“O K, pig,” he said. “Do your stuff.”

So Freddy went up to the door. He didn’t go very fast, but he went. And he rang the bell.

He waited about two seconds and then he turned around. “Nobody home,” he said. “Well, let’s go.” And he started down the steps.

But Jinx stopped him. “Give ’em time to answer, can’t you?” he said. “My goodness, Freddy, what are you afraid of?”

“I’m not afraid exactly,” said Freddy, “but—well, this is a lot bigger and grander house than I thought it would be. After all, I’m just a pig.”

“It isn’t as grand as the White House,” said Jinx, “and when we went to Florida we all went there and shook hands with the President. I guess—”

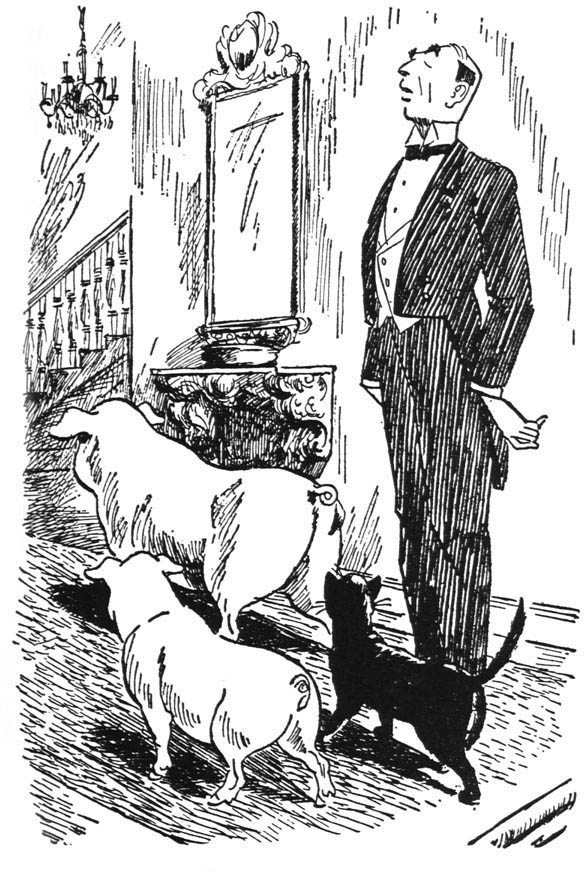

He stopped, for the door opened slowly and a very tall dignified man in a black coat with tails stood in the doorway. He was so dignified that he didn’t even lower his eyes to see who had rung the bell, but just looked straight out about two feet over Freddy’s head. And so he did not see that Freddy was a pig.

“I am—is Mr. Camphor home?” Freddy asked.

“Who shall I say wishes to see him?” the man inquired, still looking off into the distance.

“Mr. Frederick Bean,” said Freddy, who was beginning to gain confidence. “And friends,” he added.

The man stood aside. “Pray, step in,” he said. “I will see if Mr. Camphor is at home.”

“Pray, step in,” he said.

The three animals filed past him into the hall, and as he closed the door behind them, Freddy held out the card that Mr. Weezer had given him. “Will you please give Mr. Camphor this?” he said.

The man had to bend down to take the card, and then he saw them. He gave a sharp bark of surprise. “Pigs!” he exclaimed. “Oh, my aunt—pigs!” He stared for a moment, then turned suddenly and wrenched at the door. “Outside!” he gabbled. “Out with you! Shoo! Scat!” Then he gave a yell, for in stepping back as he pulled the door open, he had trod on Jinx’s tail, and the cat had clawed him sharply in the leg.

The animals were scrambling for the door when a voice called “Stop!” and they looked around to see a short red-faced man with a moustache who had come into the hall through a door at the back. “What’s going on here? Shut that door, Bannister.”

The tall man closed the door. “These animals, sir,” he said. “I give you my word, sir, they rang the bell and asked for you. If you’ll pardon my saying so, sir, I never heard of such a thing in all me life.”

“Certainly I will pardon you,” said the man, “but I don’t think that the remark is very interesting. What’s that in your hand?” And he came forward and took the card and read it. “First Animal Bank, eh? Of course, I remember seeing the sign. ‘Assets: none; liabilities: unlimited,’ or something of the kind, eh?”

“No, sir,” said Freddy, “it’s the other way round.”

“Ah,” said the man. “Well, one never knows with banks, does one?” He smiled pleasantly at Freddy, then turned to the butler. “Bannister, you’re a fool.”

“Yes, Mr. Camphor,” said the man, but he didn’t look as if he minded much.

“You are getting old.”

“As you say, sir.”

“And, Bannister, there’s no fool like an old fool.”

“I don’t know that I agree with you there, sir,” said Bannister seriously.

“Ah,” said Mr. Camphor, “that’s an interesting question. Perhaps you’re right. You believe that a young fool looks foolisher than an old fool, do you? What’s your opinion, Mr. Bean?”

“Oh, please just call me Freddy,” said the pig.

“Glad to; glad to,” said Mr. Camphor. “You may call me Jimson if you like. I’m not one to stand on ceremony. Never had much dignity. That’s why I keep Bannister, here. He has to be dignified for two of us.” He looked at the other animals. “Your friends, Mr.—ah, Freddy?”

Freddy introduced them, and Mr. Camphor shook hands with them, while Bannister stood stiffly, looking over their heads without any expression at all.

“Well,” said Mr. Camphor, “what are we standing here for? Bannister, some—ha, some refreshments on the north terrace. Come with me, gentlemen.”

He led the way through a series of elegantly furnished rooms and out a long window on to a shady terrace which faced across the lake.

“Make yourselves comfortable. Jinx, you take that chair with the cushion. Now, gentlemen, is this a—ha, a business conference or just a neighborly call?”

“I came to see you on business,” said Freddy.

“Ha, I was afraid of that.” Mr. Camphor looked unhappy. “Nobody ever pays just friendly calls on rich men. And I am a very rich man, gentlemen. That’s the trouble with having a lot of money—nobody ever comes just to see me. They always want to sell me something, or get me to give money to something, or—or something. Always something to do with money, at any rate. Never just friendly talk about the weather, and politics, and—and food.” He shook his head. “Money is the root of all evil.”

“I don’t agree with you, sir,” said Bannister, appearing with a large tray.

“Eh? You don’t?” Mr. Camphor swung around and looked at the man, who had set the tray down and was placing a large saucer of cream before Jinx. “Dear me, that’s two proverbs in one day that we have disagreed on.”

“I don’t think you believe it either, sir,” said Bannister. “If you did, you’d give all your money away, wouldn’t you, sir?”

“Ha, by George, I believe you’re right,” said Mr. Camphor. “Wouldn’t want to keep the root of all evil right in my pocket, would I? Well, Freddy, as a banker, what do you say to that?—Here, try some of these little cakes.”

“I don’t know,” said Freddy. “The money in our bank isn’t a lot of trouble, but of course there isn’t very much of it. But anyway, Mr. Camph—”

“Jimson to you, remember,” interrupted Mr. Camphor. “Though if this is a business conference, perhaps we’d better stick to the misters.” Then he smiled at Freddy. “No, no; you stick to Jimson.”

“Well, sir,” said Freddy, “—I mean Jimson; I was just going to say that while I came on business, my friends just came along to—well, to pay a call.”

“You wouldn’t say that they came out of curiosity?” asked Mr. Camphor.

“Yes, sir—Jimson, of course they did. But there’s no harm in that, is there?”

“None—ha, none at all,” agreed Mr. Camphor. “But that brings up another proverb: curiosity killed the cat. What do you say to that, Bannister?”

“I don’t believe it, sir. This cat, if I may say so, is almost too much alive.”

“I’m sorry I clawed you,” said Jinx. “But when you stepped on my tail—”

“Pray don’t mention it, sir,” said Bannister. “I should no doubt have clawed you if you’d done the same thing to me.”

“Well, well,” said Mr. Camphor, “let’s get the business part of this meeting over, and then we can get to the gossip and refreshments. What did you want to see me about, Freddy?—Bannister, kindly provide dignity for a business conference.”

So Bannister stood up very stiff, with his elbows well away from his sides, and Freddy told Mr. Camphor about seeing the advertisement, and about wanting to apply for the job of caretaker.

“Dear me,” said Mr. Camphor when he had finished. “It’s hard to tell whether you’d be suitable or not. It’s rather buying a pig in a poke, isn’t it? Not that I ever knew what a poke was, and in any case I don’t think you’re in one, so we’d better let that proverb go. But I’ve never employed a pig before.” He looked at Freddy thoughtfully. “On the other hand, I’ve never employed a bank president. A bank president as caretaker—ha, that sounds rather fine, doesn’t it? H’m, well … Of course, nobody else has applied for the job—you know how hard ft is to get help nowadays. But perhaps I’d better tell you just what the work is.” He leaned back in his chair and lit a large cigar. “I shall be in Washington all summer working for the government, but I shall come up occasionally for the weekend, so the house will not be closed. Mrs. Winch, my cook, will keep it open, and have a room always, ready for me. She will also cook the meals for the caretaker.

“The caretaker’s duties are quite simple,” he went on. “He will be a sort of policeman. He will guard the house and the grounds. In case of boys and wild animals, he will be expected to drive them away. In case of burglars, he will be expected to—ha, to capture them. But as I understand from Mr. Weezer that you are a competent detective, and in addition, a good friend of the sheriff’s, I think you would be able to manage that.”

“Yes, sir—Jimson. I think so,” said Freddy doubtfully. “Where does the—the caretaker live?”

Mr. Camphor got up. “Come to the edge of the terrace,” he said. “You see down there, where the creek comes into the lake?”

“That little house?” said Freddy.

“Yes, it’s a houseboat. Has three little rooms, completely furnished. There’s an outboard motor attached to it, so that you can cruise around the lake if you want to, and tie up for the night wherever you happen to be. It doesn’t go very fast, of course. And I wouldn’t expect the caretaker to go off on a long cruise and leave the estate unattended.”

“A houseboat!” exclaimed Freddy. “Oh, my goodness, Mr.—Jimson, I hope you will give me the job. I’d love to spend a summer on a houseboat.”

“Well,” said Mr. Camphor thoughtfully, “I think perhaps I will. Mr. Weezer spoke very highly of you. And—oh yes, the pay. The caretaker gets fifty dollars a month and the houseboat and all his meals. I trust that would be satisfactory?”

“Satisfactory!” Freddy exclaimed. “Why it’s—it’s too much! My goodness, what would I do with all that money?”

“Ha! Hear that, Bannister?” said Mr. Camphor. “Only person I ever hired who was satisfied with my first offer. The workman is worthy of his hire—ha, there’s a proverb we can try out. We’ll see if you’re worthy of your hire, Freddy. And by the way, I understand you’re something of a writer? Write poetry, eh?”

“Why, I—I dabble in it a little, sir,” said Freddy modestly.

“Good! Good! You’ll have plenty of time for dabbling. But what I wanted to suggest—As you may have noticed, I’m much interested in proverbs. You know what I mean: such things as ‘a rolling stone gathers no moss.’ Well, most people accept these proverbs as true. But Bannister and I don’t agree with ’em. Ha! I guess we don’t. We argue about them, and when we can we try them out, to prove whether they’re really true or not. That rolling stone one, for instance. We rolled hundreds of stones down that hill over there. Well, some of them did gather moss. Not much, but enough to prove that the proverb isn’t always true. If we rolled ’em down where there was plenty of moss, they picked up a little on the way.

“Well, what I wanted to say was this. If in your spare time you can examine into a few proverbs, why I’ll pay you a little extra. For every proverb you experiment with, ten dollars. How’s that? You see, Bannister and I expect to write a book about them when we gather enough facts. But we need help. And I think perhaps you’re just the person to help us. What do you say?”

Of course Freddy was delighted with the idea and said so.

“Fine!” said Mr. Camphor. “Splendid! Well then, that’s all settled. Report for duty a week from today. And now that business is over, there’s no more need for dignity. Relax, Bannister. Sit down and have a cake.”