Chapter 6

Freddy saw that Mrs. Winch was not going to be any help to him. If he told Mr. Camphor the truth about Mr. Winch and Horace, she would say flatly that it wasn’t so, that they had just come for a visit and Freddy was jealous. And Mr. Camphor would believe her. After all, he had known her longer than he had Freddy.

Probably Mrs. Winch acted that way because she was afraid of losing her job. If Mr. Camphor found out what kind of a man her husband was, he would probably fire her. Then she would have to go back and live with Mr. Winch. And she was afraid of Mr. Winch. Freddy couldn’t blame her for that. Mr. Winch was a pretty mean man.

“Just the same,” said Freddy to himself, “it’s up to me to do something, and something I will do!” Having said which, he sat down on his little porch and tried to think what that something could be. But it was getting along towards suppertime, and all he could think of was how hungry he was getting. Of course his lunch had been both large and late, but that didn’t make any difference. “That’s one trouble with being a pig,” he thought; “no matter how much you eat, you’re always hungry again in a little while. Though it’s nice, too,” he thought, “because you enjoy your meals so much.”

Of course all this thinking just made him hungrier, and at last he started up towards the house. He walked quite briskly at first, but the nearer the house he got, the less hungry he felt, and the less hungry he felt the slower he walked. Until, when he came in sight of the kitchen door, his appetite was entirely gone, and he stopped. “I guess,” he said thoughtfully, “—I guess I don’t want any supper.”

So as it seemed rather silly to go up and face the Winches again if he didn’t want anything to eat, he turned and started back. But as soon as he did that he began to feel hungry again. “Oh, dear,” he said, “I guess the only thing is to get close enough to the house so that I don’t want supper, and far enough away so that I’m not scared of Mr. Winch.” And after a little experimenting he found the exact spot, just where the path curved around to run straight towards the house. He sat down behind a bush and waited.

After a little while the man with the black moustache and the dirty-faced boy came out of the kitchen door. Mr. Winch was wiping his moustache on his sleeve, and they both had crumbs all over them, so Freddy knew they had had their supper. And when they walked down towards the lake, he went on into the kitchen.

Mrs. Winch was washing up a big stack of dirty dishes. She scolded Freddy for being late, but she gave him his supper. “You’ll get it tonight,” she said, “but in the future, if you’re late you don’t get anything. ’Tain’t part of my job to keep pigs’ suppers hot.”

Freddy didn’t say anything.

“You needn’t be afraid of them two,” she said, jerking her head towards the door. “They won’t bother you if you don’t bother them. Best thing to do is say nothing, just like I’m going to do. What Mr. Camphor don’t know, won’t hurt him.”

Freddy still didn’t reply. He ate quickly, went out, and took a roundabout course down towards the houseboat. He was hurrying through a clump of tall elms when there was a sound above him like a hammer striking a piece of wood, and a stone fell at his feet. He looked up. Nailed to one of the branches above him was a small birdhouse, from within which came an agitated chirping. And then there was another tock! and another stone dropped through the leaves.

Expert detective that he was, Freddy found no difficulty in figuring out what was going on. Somewhere at a little distance away the dirty faced boy was throwing stones at the birdhouse.

“Hey! You, up there!” he said. “Come down here. You’ll get hurt if you stay there.”

A bluebird’s head appeared at the doorway, ducked back as another stone slashed through the leaves, then the bird popped out and swooped down to a twig a few inches above the pig’s head.

“Oh, dear,” she said, “what are we going to do? My husband and I just moved in, and I was just starting to give the place a thorough cleaning when that awful boy … Oh, dear, oh, dear, whatever shall I do? My husband will be so angry if he comes back and finds I haven’t tidied up! Oh, dear—”

“Stop twittering! said Freddy sharply. “Your husband will be still angrier if he comes back and finds you’ve been hit with a rock. Where is he? Why isn’t he helping you?”

“He went up to the garden to find a worm for supper. Nothing seems to agree with him lately, and it makes him so cross. I thought a nice fresh angleworm—”

“Never mind,” said Freddy, interrupting her. “You go find him and tell him I said you’d have to find another place to live. Not around here. That boy’s going to be here for some time, I’m afraid, and he’ll make your lives miserable.”

There was a flash of blue through the trees and the bluebird’s husband lit beside her. “What’s this?” he demanded. “Who says we can’t live here?”

Freddy explained. But the bluebird was inclined to make light of the warning. “Boys always throw stones,” he said. “They can’t hit anything. As for you, sir, I’ll thank you not to interfere in my domestic affairs.”

“Have it your own way,” said Freddy. “But if you’re smart, you’ll pull out of here quick. And you’d better warn all the other birds who’ve started nests on this place, too. I know that boy.”

“But I do not know you, sir,” retorted the bird. “You had better keep your advice for those who need it. I’ll have you know—” He stopped, for they heard footsteps and, turning to look, saw Horace coming towards them. “Perhaps you’re right,” he said hastily. “Come, Elizabeth.” And they flew off.

“Oh, it’s you, pig,” said Horace. He had a handful of stones. “Let’s see how fast you can run. I’ll give you till I count ten.” He grinned and balanced a stone in his hand.

“If you throw stones at me,” said Freddy, “you’ll get into trouble.”

Horace kept on grinning. “One,” he said. “Two. Three …”

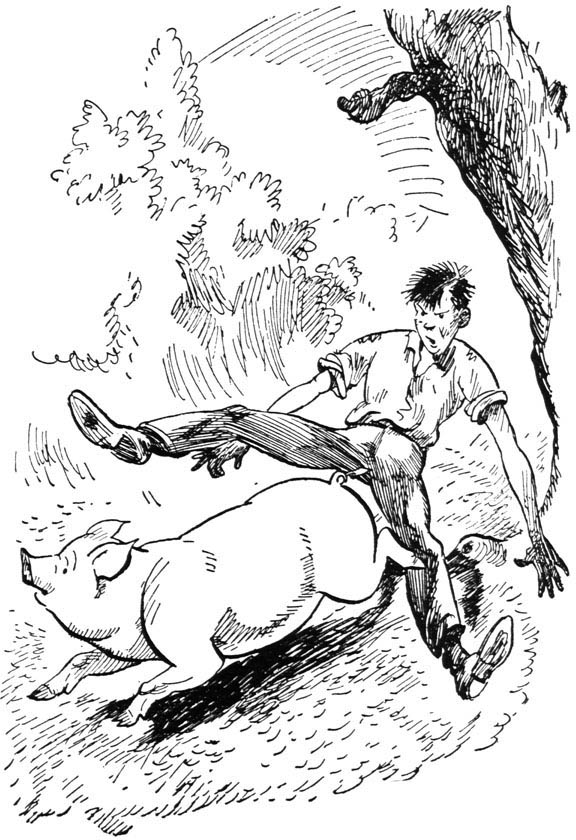

Freddy got mad. Horace wasn’t a very good shot, and the stones were small anyway; even if one of them hit him it wouldn’t be serious. But he didn’t like being bullied. He turned as if to run away, then whirled and charged straight at the boy.

Like all bullies, Horace was a coward. When he saw Freddy coming for him, he gave a yell and tried to run, but he was too late. Freddy drove right between his legs, and he flew up in the air and then landed sitting down on a protruding root. It was a large root, and it probably hurt quite a lot, but not as much as he made out. For instead of getting up he just sat there howling.

Freddy drove right between his legs.…

But Freddy kept on going. He trotted on to the houseboat, and went into his living room and locked the door. He sat down for a few minutes in an armchair, then he got up and unlocked the door and went out and shoved at the gangplank that led from the bank of the creek to the deck. He shoved it until the end of it just barely rested on the deck. “There,” he said; “now if that Horace tries any funny business, he’ll get another bump.” Then he locked himself in again.

He felt fairly safe now, but he was not very happy. When it began to get dark, he lit the lamp and tried to read a detective story. But he couldn’t keep his mind on it, and after he had read a page he would have to go back and read it all over again to see what it was about. About half past nine he heard the clatter of Mr. Winch’s car approaching along the road. Evidently he had driven off somewhere after supper and was now coming back. The noise stopped, there was the clang of the big gates shutting, then the car went along up towards the house. “If he’s locked the gates, no sense my going up there,” Freddy thought. So he read a little longer. Then he put out the lamp and went to bed.

When he awoke it was broad daylight. He lay still for a few minutes. There was something wrong, something different, but he couldn’t at first tell what it was. Then it came to him: there were no birds. Every other morning he had spent in the houseboat, that was the first thing he had been aware of—the twittering and chirping and singing of dozens of birds. He liked to lie and listen to it. Now and then one would light on the roof and hurry across it in little quick hops. But this morning not a bird could he hear. The bluebirds must have warned them, and they had all moved away.

“Well,” he said to himself, “I suppose I’ll have to go up to the house and get my breakfast.” He yawned, and then he sighed, and then he got up and washed his face and hurried out on deck. Then he stopped. “There’s something I’ve forgotten,” he said. “Now, what is it?” He thought. “Something I have to do before going ashore. What on earth … Well, I can’t wait any longer. Maybe it’ll come to me later.” And he stepped on the gangplank. And he and the gangplank went down into the creek with a tremendous splash.

He crawled out on the bank and blew the water out of his nose and shook himself. “Golly, that was it—to pull the plank up before stepping on it.” He giggled. “It came to me, all right!”

Then he saw Elmo and Waldo sitting on the bank. If they had laughed he wouldn’t have felt so foolish. But they just stared at him with their big bulging eyes, as if they were watching a clown at the circus who was trying to be funny and wasn’t succeeding very well.

Freddy stared back for a minute. But you can’t outstare a toad. “Well,” he said finally, “can’t you at least say good morning?”

“Excuse us,” said Elmo. “We were just wondering what you were trying to do. We came down to see if you’d decided anything about the rats.”

“The rats!” said Freddy. “Oh, my goodness, I’ve got more important things on my mind than rats.”

“Yeah?” said Waldo. “Such as what?”

“Such as these Winches,” said Freddy. “Tell you about ’em later.”

“What are Winches?” said Elmo.

“I’ll tell you after breakfast. Maybe you can help me.” He started up the bank.

“We thought you were going to help us,” said Elmo, but Waldo said: “Aw, let him go. How could he help anybody—pig that can’t keep from falling off his own front porch?”

Freddy went on up to the house. Mr. Winch and Horace weren’t up yet, Mrs. Winch told him. “Mr. Winch was up pretty late,” she said. “He had to drive back home to get some things.”

Freddy knew Mr. Winch had got back at half past nine. He thought that wasn’t very late. He guessed that Mr. Winch was lazy and never got up early anyway. He thought too that if Mrs. Winch was finding excuses for him, it probably meant that she intended to let him stay, and was trying to make the best of it. Freddy was pretty uneasy, and he finished his breakfast quickly and went out to make the rounds of the estate.

It was just before noon that Freddy was made a prisoner. He had about decided that the only thing to do was to go back to the Bean farm and get his friends to come help him drive the Winches away. He would have preferred to send a messenger, but now that all the birds were gone there was no one to send. He hadn’t seen a bird all morning. There were a few squirrels around, but squirrels couldn’t be trusted to get a message straight. The only thing to do was go himself.

He was in the living room, packing up one or two things that he wanted to take back to the farm with him, when he heard heavy footsteps on the deck; then the front door was slammed shut and a key squeaked in the lock. He ran to the window. A black-moustached face grinned at him through the screen.

“Hey!” he said. “What are you doing? Let me out of here!”

“Now take it easy, pig,” said Mr. Winch. “We got your best interests at heart, me and Horace. We wouldn’t want anything to happen to you, like if maybe you was to decide to run away or something, and then you got lost or hit by an automobile. Your Mr. Bean would feel pretty bad if anything like that happened. No, we’re going to take better care of you than that.” He grinned again. “Safe bind, safe find,” he said. “That’s what I always say: safe bind, safe find.” And he turned and went away.

“My goodness,” thought Freddy, “how silly I’ve been! Why didn’t I go when I had the chance! ‘Safe bind, safe find,’ eh? Well, I hope that proverb isn’t true. But I guess it is. He’ll find me when he wants me, all right.”