Chapter 9

Those had been very brave words with which Freddy had said goodbye to the toads, but as he trotted out into the road with the suitcase in his mouth he realized that he had nothing to back them up with. He had been fired for stealing, and he couldn’t even prove his innocence, much less take any measures against either the Winches or Simon. Like all people who lead very active lives, Freddy had had his ups and downs, but J. doubt if he had ever before felt quite as down as he did at this minute.

A sharp Pssssst! from a bush beside the road startled him, and he looked around to see two yellow eyes in a small black face among the green leaves. Then Jinx bounded out into the road.

“Hi, old pig!” said the cat, slapping him on the back. “Golly, we’ve been worried! We thought the old sausage grinder had got you at last.”

Freddy winced. It is not very tactful to mention sausage or bacon to a pig. But he was fond of Jinx, and so glad to see him that he couldn’t be offended. Jinx always talked in a rather rough way, anyway.

Freddy put down his suitcase. “I’ve had an awful time,” he said.

“Hi, Number Seven!” Jinx called, and a rabbit bounded out into the road. “Back to the farm and tell ’em Freddy’s safe.” And the rabbit saluted and then leaped the ditch, and Freddy watched him speeding away southward across the fields like a stone skipped over still water. “Number Eighteen!” called Jinx, and another rabbit appeared. “Stand by for orders.” Then he turned to Freddy. “What do we do—move in on these birds right away? We can have everybody up here in an hour.”

“No,” said Freddy. “It isn’t as simple as that. How long have you been here, Jinx?”

“Since yesterday. Breckenridge told us you were in some sort of trouble, so I came up with some of the others. I called at the door first—”

“Yes,” said Freddy. “I heard about that.”

“That dirty-faced boy—I recognized him, but I didn’t let on, and of course he didn’t remember me—he gave me some song and dance about you moving away. We knew it was the bunk. So most of ’em went back, and I stayed on guard with some rabbits for messengers. Breckenridge’s aunt—the one that lives up near Saranac—is sick again, so he had to go up there. That’s why you didn’t see him again. But suppose you give me the low-down.”

“I will,” said Freddy. “But I want to get back to the farm. I’ll tell you as we go along.”

“You can’t talk and carry that case,” said the cat. “See that clump of trees? Bill’s over there, and Peter’s behind the wall across the field. We thought if either the boy or the man came out we could jump out and muss ’em up. We didn’t want to go inside till we found out where you were. But we’d planned a little commando raid for tonight.” He raised his voice and gave a long “Miaouw!” and a goat dashed out from the trees, and a bear came lumbering from behind the stone wall towards them.

When these two had greeted Freddy and told him how glad they were that he had escaped, Peter, the bear, picked up the suitcase and they all started off homeward. On the way, Freddy told his story. “You see,” he said, “it won’t do much good to raid the place and drive the Winches away. I’ve got to prove to Mr. Camphor that they lied about me, and I’ve got to get back the stuff they stole, too.”

“They probably sold it,” said Bill.

“They may have sold some of it,” said Freddy, “but my guess is that Mr. Winch stole mostly things he could take back home and use, like those suits of clothes. He isn’t really a professional burglar.”

“Just a sort of hobby with him, eh?” Bill remarked.

“You might put it that way. And another thing: I heard their car driving off and coming back about once every day they were there, so I think they stole a lot more things than Mr. Camphor missed. After all, he didn’t have time to look around much. And that house is just crammed with things. You could take ten truckloads out and it still wouldn’t look as if anything much was missing.”

“Well, we know where Winch lives,” said Jinx. “We had enough trouble there when we went to Florida.”

“Sure,” said Peter. “We’ll hitch up Hank to the old phaeton and go down there and get the stuff.”

“Something like that,” said Freddy. “We’ll have to work out some plan together. But right now—well, I’m so glad to be getting home that I’d rather not think about those people for a while.”

So the rest of the way they told him all the farm gossip.

When they had gone over the hill through the Big Woods, and were coming down through Mr. Bean’s woods, Freddy said he’d like to avoid the duck pond on his way back to the pigpen. “Uncle Wesley will want to hear all about it,” he said, “and he’ll have a lot to say, and I don’t want to talk about it right now.” So they didn’t follow the brook down, but came out of the woods higher up, where Mr. Bean had planted his big Victory Garden.

Some of the vegetables were already coming up, and Freddy stopped to look at the neat rows of green shoots. “My goodness,” he said, “Mr. Bean certainly does plant straight rows! And how nice they look!”

“Yeah,” said Bill, “and they’re going to look a lot nicer if Mr. Webb gets his ideas across.” Mr. Webb was a spider who lived in the cowbarn in the summer. He was small and plump and black and he had eight legs, and his wife, Mrs. Webb, looked just like him, except that she wore bangs. They were very popular.

“What do you mean?” Freddy asked.

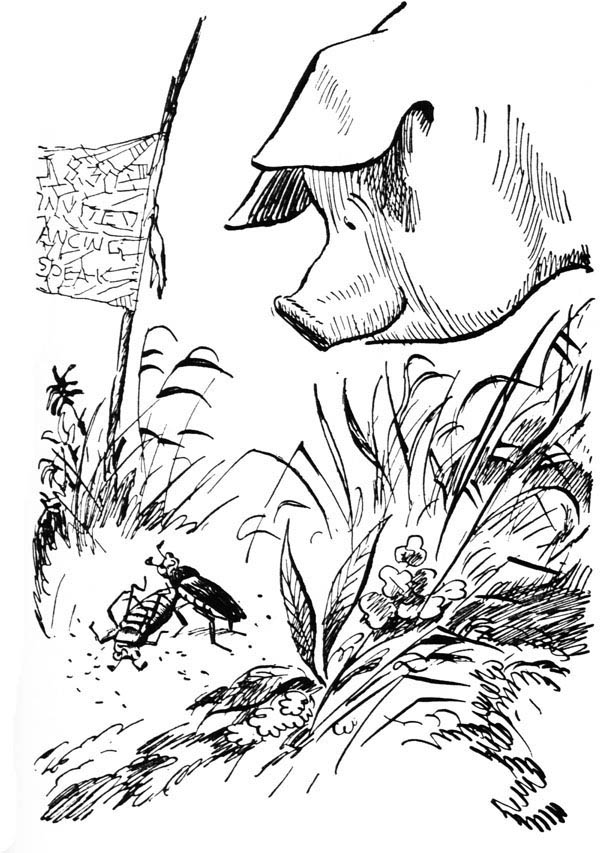

“Come over here,” said Jinx, and he led the pig around to where, on one side of the garden, two tall dead stalks of last year’s goldenrod were still standing. Between them he could see that something was hung, something that shivered and shimmered in the light breeze. And then he saw that it was a sign, woven of spider web, like the signs that are sometimes hung out above the streets at election time, telling you who to vote for.

Freddy went closer and read it. “Patriotic Mass Meeting. Tonight at 8:30. All Bugs, Beetles and Caterpillars Invited. Fireworks, Music, Dancing. Mr. Webb will speak.”

“I don’t get it,” said Freddy. “What’s he going to talk about?”

“I think he’d like to tell you about that himself,” said Jinx. “He’s been hoping you’d get back, so you could help him. For one thing, he wants you to type out some signs like this for other meetings. It took him and Mrs. Webb two days to weave this one, and then a horsefly got into it and they had to spend another day repairing it. He wants you to fix up a megaphone, too. If they have a big meeting, those in the back rows won’t hear much.

“Look, Freddy. He’s asked the animals to stay away, because he’s afraid that if we came we might step on some of the audience and squash ’em. But if you make him a megaphone and bring it up tonight, he’ll be willing to let you stay and you can hear what it is all about.”

Freddy agreed, and they went on down to the pigpen, where he thanked them for their help, and said he guessed he’d go in and rest a while, as he was pretty tired.

“O K,” said Jinx. “But don’t forget the megaphone. Mustn’t let the old boy down.”

So a little after eight that evening, Freddy started out. He had the megaphone with him. He had made one the summer before for Jerry, an ant who had lived with him for a while. It was just a cone of stiff paper. If Mr. Webb got down in the narrow end, even with his little voice everything he said would come out good and loud.

When he got to where the sign was hung, beside the garden, he found that hundreds of bugs had already assembled. It was beginning to get dark, and he had to walk very carefully not to step on any of them. He didn’t see the Webbs anywhere around, but as he tiptoed along, two large beetles stopped in front of him and waved their feelers.

“Evening, Freddy,” said the larger one. He had a rather husky voice which could be heard plainly without using the megaphone. “I’m Randolph—I guess you remember how you helped me with my legs, don’t you?”

“Of course,” replied the pig. “Nice to see you again.”

“This is my mother,” said Randolph, and the other beetle tried to drop a curtsey, and immediately sat down hard and then fell over on her back.

“Drat it!” she said.

“Never could get mother to use her legs properly,” said Randolph as he rolled her right side up again. “Shove that megaphone around for me, will you? I’m master of ceremonies tonight. Webb’ll be along any minute now, so I’d better get ’em ready for him.”

“Never could get mother to use her legs properly.”

Freddy pushed the large end of the cone around so that it faced the open space where the audience was to sit, and then Randolph went to the small end and chewed a hole there and spoke through it. “Ladies and gentlemen! Your attention, please!”

The crowd of insects, who had been hopping and crawling around, stopped and turned towards the speaker.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” said Randolph, “as you know, our distinguished friend, Mr. Webb, has called this meeting for a purpose. What that purpose is, he will himself explain to you presently. But it is no secret that his message is a patriotic message. Mr. Webb, with the able assistance of his wife, has gone to considerable trouble and expense to provide you with an evening of very superior entertainment, a veritable galaxy of stars, such a display of talent as I venture to say has never before been brought together. But I must ask you to remember that the real purpose of this meeting is a serious purpose, that Mr. Webb’s message is of vital importance to each and every one of you, as well as to the great nation of which you and I are humble citizens. Enjoy yourselves, therefore, but when you go home, give serious consideration to the words that Mr. Webb has spoken.

“And now,” he said, “while we are waiting, we will have a tune from the orchestra.”

Four treetoads, and a dozen or so katydids, crickets and other insects which Freddy didn’t recognize, came forward. They took places in front of the megaphone and the largest katydid waved his feelers and they started to play, trilling and chirping and rattling for all they were worth.

“Well, this may be all right,” said Freddy, “but it doesn’t sound like music to me. Modern stuff, I suppose?”

“No,” said Randolph, “it’s because you don’t hear it as we do. It sounds pretty loud down in the audience. Here, put your ear to the small end of this megaphone.”

So Freddy did. The sounds came through much louder to him, and he did think that he could distinguish a sort of tune.

“Well, it’s queer all right, and they keep good time,” he said, “but it isn’t anything I’d pick out to listen to. And say, what is this great message of Webb’s anyway, Randolph?”

“Stick around,” said the beetle; “you’ll hear it.” He looked around. “Getting pretty dark; I guess we’d better put on the lights.” And he shouted: “Lights!”

Immediately several hundred fireflies, who had been stationed on the tops of the tall grasses that surrounded the open space, turned on their lights. Others on the ground in front of the musicians acted as footlights.

“Here come the Webbs now,” said Randolph, looking up to where a huge Luna moth was circling above them. “He thought it would be more dramatic to arrive by plane.”

The moth dropped down and lit on the low branch of a small tree that stood beside the garden, and the two spiders spun themselves swiftly down on strands of web. Mrs. Webb swung across and landed on Freddy’s ear.

“Splendid of you to make this megaphone, Freddy,” she said. “I knew I could count on you if you got back. We were going to try to use a morning glory blossom, and I had one all picked out, but I forgot that the miserable things close up at night. I doubt if it would have been big enough anyway. I’ll sit with you while father is talking. You’ll stay, won’t you? He wants to talk to you afterward.”

Freddy said he would. The orchestra had stopped and there was much excited applause—which didn’t sound much different to Freddy than the music. Then Mr. Webb took his place inside the megaphone, at the narrow end.

“It is a great pleasure to me,” he said, “to see so many familiar faces here tonight, and an even greater one to see so many unfamiliar faces. Although the high quality of the entertainment provided would no doubt have brought many of you here, I am sure that the appeal to your patriotism is the real reason for this huge audience.

“Now my friends, I am not much of a speaker. Let’s get the serious part of our program over, and we can devote the rest of the evening to pleasure. As you know, our country is now engaged in a great war. We of the insect world cannot fight. We cannot buy bonds. But there is one thing we can do. Let me explain very briefly.

“One of the most important weapons in this war is food. Our farmers are working night and day to produce food to feed not only our own soldiers and the people at home, but to help feed our allies. They have to raise bigger crops than ever before. And there are fewer of them, because so many have gone into the army. In order to increase the crops, the President has asked everyone who can to plant a Victory Garden. This garden on the edge of which we meet tonight, is Mr. Bean’s Victory Garden.

“I see here tonight representatives from every walk of insect life. I am glad of that, for you can all help. Some, of course, more than others. I refer to the potato bugs, squash bugs, cabbage worms, cut worms, leaf hoppers, grasshoppers, caterpillars, and others whose main diet is garden vegetables. Now in ordinary times Mr. Bean does not grudge you what little you eat. It’s only when there are too many of you and you begin to destroy his whole crop that he tries to drive you away. But this year I don’t think that you should destroy any of the crop. Mr. Bean is rationed in what he eats, and if you are patriotic bugs, you won’t object to being rationed too. And I believe that you are patriotic bugs. And so I am going to ask you to agree not to eat any vegetables at all this year. I’m going to ask you—” He stopped, as a potato bug in the front row jumped up and began waving his forelegs excitedly. “Yes, what is it?”

“It’s all very well to ask us to be patriotic,” shouted the potato bug, “but what do you want us to do—starve? You’re a spider; you don’t like vegetables anyway. Besides, us potato bugs don’t eat the potatoes; we only eat the leaves and vines.”

“When you eat the vines, the potatoes don’t grow,” said Mr. Webb. “But nobody’s asking you to starve. There are plenty of other things you eat that aren’t vegetables. There’s nightshade vines, for instance. I know you potato bugs like nightshade, for I’ve seen you eating it. And there’s enough up there in the woods to feed a million of you all summer. There are hundreds of seeds and wild plants in the fields and alongside the roads—something for every taste. There’s milkweed, now. Most caterpillars like it. Maybe it isn’t quite as tasty as garden vegetables, but I’m sure for the duration you’ll all be willing to go without some of the things you like for your country’s sake. How about it, bugs? Let’s have a show of hands. How many are willing to give up something to help win the war?”

Freddy had never thought of bugs as being specially patriotic, and he was surprised when the entire audience suddenly burst into wild and frantic cheering. Of course some of them couldn’t cheer, but they waved feelers and forelegs and the caterpillars reared up and swayed back and forth, and even the little flea beetles hopped up and down like tiny rubber balls.

“Thank you, my friends; thank you,” shouted Mr. Webb. “I was sure I could count on you. Now I have only one more thing to say. I would like to have some volunteers who would be willing to go out to other farms in the county and organize other groups like this one. I expect to hold a number of meetings myself—indeed, I have already held a good many—but I can’t do it all alone, and moreover, an appeal to give up vegetables would come better from someone who is himself making a sacrifice, than from me, who as our friend the potato bug has remarked, do not eat vegetables. I will arrange transportation, of course, and all other details. Some time, therefore, during the dance which immediately follows, please speak to either Mrs. Webb or me about it.” He nodded to the orchestra leader, who at once led his musicians into a gay dance tune. And in less than a minute, every bug in the audience who could hop, skip or crawl, had chosen a partner and was dancing like mad.