Chapter 10

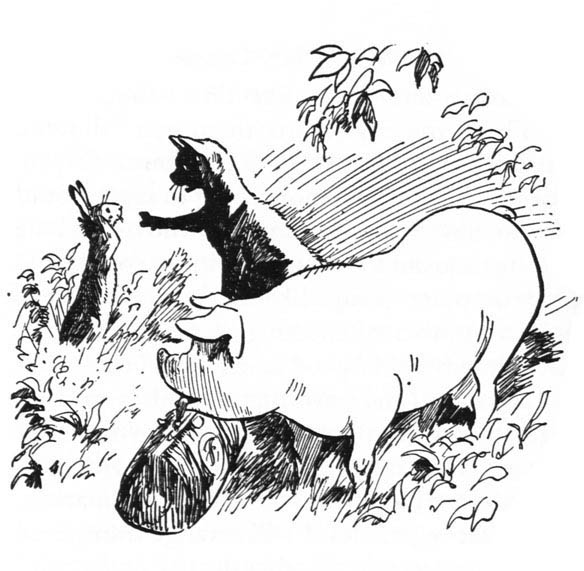

Randolph was one of the first dancers on the floor. He led his mother out and they started a sort of slow prance. At every third step his mother got her legs mixed up and fell down, and had to be righted and started off again. But she stuck to it gamely, and as they were rather heavier than most of the other dancers, they soon had a clear space to themselves.

Freddy was very much interested in the different styles of dancing. The caterpillars faced each other with their noses almost touching, then they would take three steps in one direction, then three steps back, then three to one side and three back. Then they would rear up and bow to each other. It was quite majestic.

The crickets danced in a much less dignified way, whirling and kicking up their feet, and occasionally shifting to a position side by side, when they would give a run and then a high leap, which frequently carried them right over the heads of the other dancers into the darkness beyond the floor. Perhaps the most graceful of them all was a pair of grasshoppers, who danced a sort of tango, with many glides and long steps, and quick turns. Although the floor was pretty crowded, it didn’t bother them any, for if other bugs got in their way they just stepped over them.

Freddy, who like many rather fat people, was an excellent dancer himself, was thoroughly enjoying himself and was getting a lot of ideas for new steps, when suddenly a loud crowing voice above him called out: “Ladies and gentlemen. Friends and fellow bugs!” and he looked up to see Charles, the rooster, perched on the low branch above him.

The orchestra stopped, and all the bugs looked up—some of them rather fearfully, for roosters occasionally like to vary their diet of grain with a nice fat bug, and there were many present who had lost friends and even close relatives gobbled up in this heartless way.

“Friends and fellow bugs!” said Charles again.

“Oh, go away, Charles!” said Freddy. “Why do you have to butt in and break up the party? You’re nobody’s fellow bug! Go on home, like a good fellow.”

“Oh, shut up!” said Charles crossly. “You know I always speak at meetings. I just heard about this one, and I hurried right up here.” And he puffed out his chest and began:

“Friends and fellow bugs! It is a great pleasure for me to address such a distinguished gathering this evening. Particularly as I am sure there are few among you who have ever before had the privilege of hearing me speak. Correct me if I am wrong—”

“You’re wrong, all right,” grumbled Freddy. “Privilege indeed! It’s torture!”

But Charles paid no attention. “However, let that pass. Our able, if somewhat prosy friend, Mr. Webb, has outlined for you his plan for helping the war effort. It is a good plan, a carefully thought out plan, a plan which has my heartfelt approval. Yet I believe there is more, much more, to be said.”

“If there is, you’ll say it, all right,” said Freddy.

“My friends,” Charles continued, “you are the small people of the world, the humble people. You take no part in great events …”

Mr. Webb had hurried over to the nearest firefly and was deep in conversation with him.

“What, you wonder,” said Charles, “has the war to do with you? What effect can your tiny efforts have on the march of events? You cannot fight, you cannot drive the invader from your shores—”

“There isn’t any invader on your shores,” said Freddy.

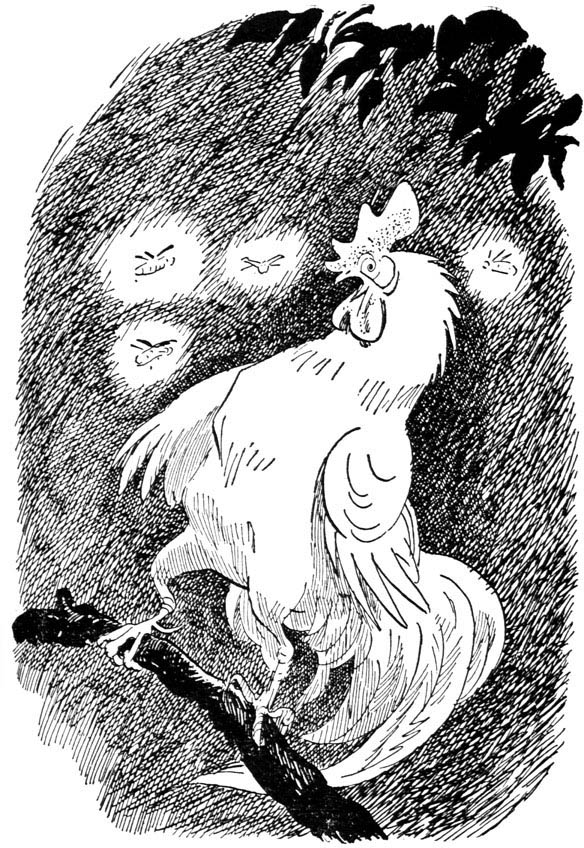

“As our learned friend observes,” said Charles, giving the pig a dirty look, “there is, at the moment, no invader. But if there were, what—what—” He paused, and blinked his eyes, for a dozen or so fireflies had come up and were flying in a circle around his head with their lights on. He took a deep breath. “Yet let me say this, my friends,” he went on determinedly, “and I say it in all seriousness. On your shoulders rests a great—nay, a well-nigh overwhelming responsibility. And so I counsel you: put your shoulder to the wheel, put your hand to the plough, put your ear to the ground, put your—put your—put your—” He began to repeat like a phonograph whose needle has got stuck, and as the fireflies circled faster his eyes, and then his head, went from side to side, as if he were watching a tennis match. Each time as they went by his head went farther around, as if he couldn’t help trying to keep his eyes on them. “Put your—put your—” he muttered desperately. And then at last his head went nearly all the way around and with a squawk he fell right out of the tree.

… with a squawk he fell out of the tree.

Charles picked himself up, but he was so dizzy that he immediately fell down again. Freddy helped him to his feet. “Darn bugs!” said the rooster. “That’s a fine way to treat me. Me, that’s the best speaker this side of Albany! Me, who’s responsible for what little patriotism there is on this farm.”

“Rubbish!” said Freddy. “You’d have been responsible for putting ’em all to sleep if you’d gone on a little longer.”

Charles leaned heavily on the pig. “Is that so?” he said angrily. “That’s a fine way to talk to one of the most useful people on this farm.”

“You’re useful all right. You crow in the morning and wake us up, and you make a speech in the evening and put us to sleep. That’s fair enough.”

Charles shook himself free. “Aw shut up,” he said, and staggered off home.

The dance had resumed, and Freddy lay down and watched again. Between the dances, the fireflies gave the fireworks display. They imitated rockets and Roman candles, and a lot of them took their places on a web in the form of an American eagle that the spiders had spun on the tree trunk. The applause for this was almost frenzied.

Freddy saw the Webbs bouncing around together in the middle of the floor, and as he watched, a cricket cut in and whirled Mrs. Webb rapidly away from her husband. Mr. Webb came back to talk to Freddy.

“Nice party, isn’t it?” he said. “But I’ll tell you, Freddy; things aren’t as smooth as they look. You remember that fresh horsefly, Zero? Well, he’s back. He’s been away to some school or something, I don’t know—but anyway, he’s learned to spin webs. Just like spider webs, they are. Don’t ask me how he does it!

“Well, for a while we didn’t mind much, though he gave us a lot of trouble. Mrs. Bean is proud of being a good housekeeper, and so when we’re in the house we just spin a small web, out of sight somewhere. But this Zero, he got in and spun webs all over the picture frames and on the dishes on the shelves, and one night he even spun one on Mr. Bean’s whiskers when he was asleep. Of course the Beans blamed us for it, and Mrs. Bean swept all the webs down, including ours. I don’t think Zero meant any special harm by it; it’s just his idea of a joke. But mother gave him a good talking to. And I guess that made him mad, for ever since we moved out in the cow barn for the summer, he’s been making a nuisance of himself. He gets in our webs and tears ’em to pieces, and spins his own webs where they’ll bother the animals—over their food dishes and on their faces when they’re asleep. And of course they think we do it.

“But the worst is, that just since we started this campaign to get the bugs to stop eating vegetables, he’s done everything he can to break it up. He tore down our sign, and we had to weave it over again. And he goes around talking, telling everybody we’re crazy, and the little they eat won’t amount to anything. He’s just plain unpatriotic, Freddy.”

“Can’t you get the wasps after him, as we did before?”

“Jacob went after him one day,” said Mr. Webb. “But Zero has got a lot of webs around in out-of-the-way corners, and he’d dodge behind ’em, and Jacob would go zooming into them. After Jacob had untangled himself from about five webs, he gave up in disgust.”

The music had stopped again, and Mrs. Webb came and joined her husband. She sat down and fanned herself vigorously with a foreleg. “Good grief!” she panted. “I’m too old to be cutting such didoes! Though I must say it’s lots of fun. But why didn’t you cut in again, father? That cricket’s a fine dancer, but he’s the athletic type. My feet weren’t on the floor more than half the time.”

“It’s good for you, mother,” said Mr. Webb, “to get shaken up a little.—Hey!” he exclaimed suddenly. “What’s all this?”

A big horsefly had buzzed down in among the dancers, who were applauding for an encore. With his strong wings humming like a little airplane propeller, he skated in circles about the floor, knocking over the other insects, who scrambled to get out of his way. “Hi, folks!” he shouted. “I’ll show you some dancing that is dancing! Whoopee! Out of the way, strut-and-wiggle!” he cried, barging into a grasshopper couple who were swept aside in a tangle of long legs. “Eee-ee-yow! This is Zero’s night to buzz!”

“Come on, mother,” said Mr. Webb with determination, and the two spiders left Freddy and made for the intruder.

Flies are rather cowardly insects. Zero must have known that the sweep of his wings would knock the spiders aside before they could close in on him, but when he saw them approaching, he flew up and perched on a tall grass stalk that overhung the dance floor.

“Ha, ha!” he shouted. “Frowsy old Webb and his fat wife! You bugs are a dumb lot to let them tell you what you can and can’t do. Is this a free country or is it going to be run by a couple of small-time spiders? Telling you to be patriotic! Patriotic your grandmother! Go on eat what you’ve always eaten. You bet if old Webb liked potatoes he wouldn’t be handing out any such talk. The old kill-joy!”

Freddy thought some of the audience were inclined to agree with Zero. He saw them nodding and talking together. The Webbs were climbing the grass stalk to get at Zero, but before they reached him the fly flew over to the sign the spiders had woven with so much work, and started beating it to tatters with his wings.

“I’ll make a sign for you,” he said, and to Freddy’s amazement he began weaving something in the hole he had torn. He worked quickly, and before the Webbs could drop to the earth and start up after him again, he had finished. The letters straggled unevenly, but they were plain. “Vote for Zero, the peple’s frend.”

“There,” said the fly; “if you want somebody to tell you what to do, hold an election. That’s the American way. Don’t let some old eight-legged frump without any neck kid you into—”

Freddy had lain perfectly still, and big as he was, Zero had not noticed him. Perhaps the fireflies’ flickering lights confused him, for horseflies don’t usually go out much at night. But now Freddy stood up suddenly, and with a swipe of one fore trotter smashed the sign and its support and Zero down into the grass.

And now if Freddy had had luck, or if he could have seen better what he was doing, Zero’s career might have ended right there. For he was entangled in the grass blades, and Freddy slapped down hard several times, aiming at the sound of frantic buzzing as Zero tried to free himself. And then he did free himself. And as he whizzed by Freddy’s ear, he gave again his irritating laugh. “I’ll be seeing you, pig. But you won’t be seeing me.” And his laugh died away in the distance.