THE Hermione’s crew during the first seven weeks of Captain Pigot’s command had slowly split into two almost antagonistic groups. The smaller comprised the couple of dozen seamen and petty officers who had come on board with Pigot, and they were referred to as the ‘Successes’ by the second group, which was made up of the 150 men who had served under Captain Wilkinson and called themselves ‘Hermiones’.

This was not because of any particular loyalty to the ship, although nearly every warship normally had a solid nucleus of men who stayed in her for several years at a time (in the Hermione at this period it numbered about forty, less than a quarter of the crew); but apart from this nucleus there was usually a fairly rapid turnover of men owing to sickness, death and desertion, and the steady drain of seamen and petty officers sent off as prize crews. The arrival of a couple of dozen Successes should not have caused any problem: normally they would be quickly absorbed, losing their separate identity.

Why, then, did the two groups form in the Hermione? The reason is not hard to find: Captain Pigot was treating the former Successes with more leniency than the Hermiones. At first this might have been due to the fact he had hand-picked the Successes and knew them well, whereas the Hermiones were strangers. But later he was succumbing to his penchant for playing the game of favourites. He was not the first person, whether captain, schoolmaster or politician, to try to use a small clique to increase and buttress his power, mistaking sycophancy for loyalty, and later discovering that he had been outmanoeuvred, and that the clique had been using him.

Richard Redman, a quartermaster’s mate from the Success, wrote of this period: ‘There was a continual murmuring among the Hermione’s [original] ship’s company concerning his [Pigot’s] followers and the usuage [sic] they had before Captain Pigot came on board.’ Since there is no doubt Wilkinson had been a harsh captain and, bearing in mind that Redman himself was one of Pigot’s favourites, it is an important clue to the new captain’s behaviour.

The Hermiones’ jealousy was soon unwittingly fanned by Pigot, because when the frigate arrived in Port Royal with the captured brig and began a refit, he arranged for the ex-Successes to be paid some prize-money owing to them. This was a perfectly normal action, of course, and was undoubtedly one of the reasons why the men had agreed to transfer to the Hermione with him. It certainly caused no jealousy among the Hermiones, but Pigot’s next action did: as soon as the money was paid, he told the ex-Successes that they ‘could go on shore for a day’s liberty’, according to Richard Redman, but he put them on their honour ‘to come back on board at Sunset’.

The jubilant men were rowed to the shore, the envy of nearly 150 original Hermiones, many of whom had hardly set foot on dry land for as long as four or five years, apart from brief wooding and watering expeditions. It is to the credit of the ex-Successes that they all returned on time: but they were picked men.

A few days later eight of the original Hermiones gained their complete freedom, thanks to the intervention of the American Consul in Port Royal, by claiming that they were American citizens. Among them was one man who enters the narrative later, Benjamin Brewster. He was twenty-three years old and came from Preston, Connecticut. From the day they were brought on board their claim to have been born in America was not disputed, since the ‘Where born’ column of the muster book recorded their birthplaces in the United States.

The order to free the men came from Sir Hyde Parker, who had been involved in a long correspondence with Mr Silas Talbot, the American Consul at Kingston.

On the same day that the Americans were discharged, the whole crew of the Hermione were mustered, and a check through the muster book shows there was still a cosmopolitan ship’s company on board totalling 172 officers and seamen, plus six Marines and three boys.

The birth-places of the fifteen warrant and commission officers are not given. Of the remaining men on board forty-seven were English, two Welsh, eighteen Irish, and ten Scots. Among the rest were four Americans, three Italians and three Swedes, and one each from Spain, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Prussia, Nova Scotia, Hanover, France, St Thomas and Barbados. Of those whose birthplaces were not listed, thirteen had foreign-sounding names.

With her refit completed the Hermione left Port Royal to return to the Mole. She had lost eight trained seamen, thanks to the efforts of Mr Silas Talbot, but at last Captain Pigot had found a clerk. When John Mansfield Manning joined the ship on April 7 he was rated an able seaman, but within a day or two Pigot made him clerk—a very welcome promotion which meant that he left the cramped life on the forward part of the lowerdeck, where he had the regulation width of fourteen inches in which to sling his hammock, for the comparative luxury of a tiny cabin just forward of the gunroom on the port side, sandwiched between that of the Boatswain and the Marine Lieutenant. The boy William Johnson, who had been acting as Pigot’s writer, was sent back to serve as a seaman.

The short voyage to the Mole was uneventful; but as the frigate came into the anchorage there was a man on board the storeship Adventure, anchored nearby, who watched her arrival with great interest. His name was Thomas Leech, and because he had just heard that Captain Pigot now commanded the Hermione he was trying to make up his mind what to do next. Leech was a seaman with an unbalanced personality and a guilty past, since over his head hung the grim wording of the 15 th Article of War—‘Every person in or belonging to the Fleet, who shall desert, or entice others to do so, shall suffer death, or such other punishment as the circumstances of the offence shall deserve…’

Leech was to become one of the leading characters in the tragedy of the Hermione, and his relationship with Captain Pigot was a strange one. He was a deserter—in fact a veteran in that dangerous occupation—but different from most deserters in two respects: he had twice been successful, and each time he had returned to serve in one of the King’s ships.

He had started his career as a deserter three years earlier when serving in the Success which, in July 1794, was commanded by Captain Pigot’s predecessor. One night while the ship was in Port Royal he had quietly climbed down the ship’s side and swum to the shore. Eventually the letter ‘R’ for ‘Run’, was marked against his name in the Success’s Muster Table, and most of the officers and men forgot about him. Most, but not all.

Several months later, after Captain Pigot had taken over command of the Success, the frigate was at anchor off St Marc when a sudden squall made a transport ship drag her anchors and crash alongside the Success. While the frigate’s crew were busy trying to get her clear several of them saw Leech on the transport’s decks, and far from trying to avoid being recognized, he chatted with them. He was soon spotted by John Forbes, the young Master’s Mate, who promptly leapt on board the transport and went straight to her captain, claiming Leech as a deserter from the Success.

He was taken back to the frigate, where Captain Pigot listened to Forbes’s report and questioned other warrant officers about Leech’s character and previous behaviour under the former captain. He was a good seaman—they all agreed on that, and the descriptions they were later to give on oath are interesting. According to Forbes, Leech was ‘sober, attentive to his duty, and at all times obedient to command’. The Master-at-Arms gave him a similar testimonial, adding that he ‘always did his duty cheerfully’. Thomas Jay, the Boatswain’s Mate, agreed, and described him as ‘a quiet man’.

In view of the favourable reports and because Leech had deserted from the ship while she was under his predecessor’s command, Pigot decided to give the errant seaman another chance, providing he promised never to desert again. Leech cheerfully gave his promise, was freed and his name restored to the Muster Table.

For a while all went well with Leech: Pigot was later to declare that he ‘always found him during the time he was under my command a sober, attentive seaman, and always obedient to command, and his conduct gave me so much satisfaction that shortly after he was brought on board the Success I stationed him to do his duty as captain of the foretop’. That alone indicated Leech was a good sailor because the topmen, who handled the sails on the upper yards of the three masts, were the most agile and expert seamen on board.

Clearly Pigot liked Leech, because the seaman’s ability was not enough to account for the kindness and leniency with which Pigot was to treat him later. He must have been an engaging rogue who became one of Pigot’s favourites—for a rogue he certainly was, and a murderous one at that.

Forgiveness and promotion were enough to keep Leech happy for a few weeks; but he soon began feeling restless again, and confided his thoughts to the Yeoman of the Sheets, William Brigstock, who came from New York. The pair of them decided to desert, and on the night of August 22, 1796, while the Success was at anchor at the Mole, both men left their hammocks and crept up on deck, intending to swim for the shore. Leech was the first to go over the side, but before Brigstock managed to strip off his clothes he was seized by the ever-alert Master’s Mate, John Forbes, who was making his rounds of the ship, and arrested. When the ship’s company was mustered at daylight there was only one man missing—the only one who had promised never to desert.

Leech had in the meantime safely reached the shore and signed on in a merchant ship aptly called the Free Briton, giving his name as Daniel White. She had sailed for Providence, Rhode Island, some 1800 miles away, before any Royal Navy officers had time to search her. However, by the time she reached her destination Leech was once again feeling restless. He was certainly not seeking his freedom on land—it would have been easy enough to get work at Providence; and only a little effort would have equipped him with a ‘Protection’ declaring he was an American. Or he could have stayed on board the Free Briton. What he actually did seems inexplicable.

Also in Providence at this time was a British warship, the 16-gun sloop Lark. One would have thought that to Leech she represented the very tyranny from which he had just escaped, since twice he had risked hanging in order to quit the King’s service. If he was caught this time the chances were that he would swing by his neck from the yardarm.

Leech knew all this only too well; but instead of keeping out of sight he packed his seabag, left the Free Briton, and went across to HMS Lark, where he reported to a master’s mate that he was a deserter from the Success.…

The Lark’s captain, who was bound to send him back to the Success, transferred him to the Swallow a few days later. By the time she arrived at the Mole in April, 1797, the Success had already sailed for England and Pigot had exchanged into the Hermione. For the time being Leech was transferred to the storeship Adventure under open arrest until Sir Hyde decided what to do with him.

When the unpredictable Leech saw the Hermione coming into the Mole under Captain Pigot’s command, he probably thought that having once been forgiven he might work the same trick again. He promptly went to one of the Adventure’s lieutenants, John Copinger, who was standing on the quarterdeck, and explained that as his former commanding officer was now in the Hermione, could he be put on board her?

But while talking to Lt Copinger he had already been spotted from the Hermione by the sharp-eyed John Forbes, who was at once ordered by Captain Pigot to go across and claim him. When Forbes boarded the Adventure he was greeted by Lt Copinger who told him they had a man on board called Daniel White who had deserted from the Success while she was under Captain Pigot’s command. Forbes, however, was intent on first getting hold of the man he knew as Leech, so he went to the Adventure’s commanding officer, Captain W. G. Rutherford, and explained that he had just seen Leech on board.

Before Captain Rutherford and Forbes realized that White and Leech were the same man. Leech himself came along the starboard gangway and spoke to Forbes, saying he had given himself up to the Lark as a deserter some weeks earlier.

So once again Leech found himself under Captain Pigot’s command. The ship was strange to him but, of course, there were several of his former shipmates from the Success on board—among them Archibald McDonald, the Master-at-Arms, who was waiting to arrest him.

Within a week of the Hermione’s arrival at the Mole, Sir Hyde Parker managed to trap and destroy another Hermione which had been causing him a great deal of trouble. She was a French frigate which had been lurking about in the Santo Domingo-Puerto Rico area for some months, and as soon as a British frigate arrived at the Mole to report she had driven the Hermione into a bay a few miles up the coast, Sir Hyde sailed with three ships, and the French frigate was destroyed.

However, the enemy were about to suffer an even greater loss: the French Hermione had originally been based at Cape François, more than 150 miles along the coast to the eastwards, where the French forces were desperately short of supplies. The French authorities there knew that their privateers had captured several American ships loaded with provisions for British ports, and sent them into the French-held Port de Paix and also Juan Rabal, nearby.

Since the privateers dare not risk the 150-mile voyage to Cape François with their prizes, the French authorities had ordered the Hermione to go and convoy them back. Her captain had advised against the venture but he had been overruled. Her destruction before she even reached Port de Paix showed his wisdom.

It also left the French prizes still in the two ports, where Sir Hyde had spotted them while on his way up to find the French frigate. There were fourteen in Juan Rabal, most of them at anchor ‘half a musket shot from the shore’ and protected by a battery of five 32-pounder guns.

‘… It appearing to me practicable to cut them out’, Sir Hyde later wrote to the Admiralty, he ordered Pigot in the Hermione to take the Mermaid, Quebec, Drake brig, and Penelope cutter, ‘and execute that service’. Sir Hyde did not explain how he had allowed French privateers to establish themselves within twenty miles of Cape Nicolas Mole and capture fourteen prizes so near to a large British base.

The Mermaid, still under Otway’s command, carried Sir Hyde’s orders to Pigot, and at sunset on April 19 the four commanding officers were rowed over in the gathering darkness to the Hermione for a conference with Pigot. In addition to Otway there were John Cooke of the Quebec, John Perkins, who was commander of the Drake, (like the cutter, she was too small to be commanded by a post captain), and Lt Daniel Burdwood of the Penelope.

Pigot showed them his orders from Sir Hyde, and it is easy to imagine the enthusiasm of the five young men—for Pigot, at twenty-seven, was the eldest—as they sat round a table in Pigot’s cabin discussing by lantern-light the best way of cutting out the ships. Pigot’s plan was quite simple: he would approach Juan Rabal at night from the eastward, and when the squadron was within two miles of the anchorage the boats from all five ships would be sent off to cut out the prizes. The frigates, brig and cutter would then follow under easy sail, keeping about a mile from the shore. If and when the French shore batteries mentioned by Sir Hyde spotted the boats and opened fire—and incidentally revealed themselves—the squadron, hidden in the darkness further offshore, would reply and draw the French fire, allowing the boats through unscathed.

Pigot worked out the distance and realized that with the present light wind and the current—which was setting against them—there was no chance of reaching Juan Rabal before daylight. He therefore decided to head out to sea for the rest of the night and then turn back next day, timing it so that the squadron would arrive off the coast after dark the following evening.

The commanding officers returned to their ships. For the rest of the night, and until 3 p.m. next day, the squadron steered northwest, then turned back towards Juan Rabal. With the current running at an uncertain speed right across their course, it would be very difficult in the darkness to find Juan Rabal: if they could not see the anchorage they would not know whether it was to the east or west. The easiest way of making sure was deliberately to steer to one side, so that on finding the coast they would know which way to turn. Pigot chose a point to the eastward, planning to arrive there ‘before the land wind came off’.

By midnight the squadron had closed the shore and were running down to the westward. So far everything had gone well: ‘We had succeeded to my wishes’, Pigot recorded. Finding the anchorage was not too difficult: they could see the outline of Point Juan Rabal, which was low and prominent, and backed by a conspicuous mountain whose peak looked like a ruined castle. Having identified the Point, the rest was easy: the privateers and their prizes were in the anchorage two miles to the westward. Pigot therefore hove-to his squadron a mile offshore, far enough out to avoid outlying rocks but close enough to hear the weird yells and squawks of wild animals, and the half boom, half swish of the waves breaking fretfully on the beach. In each of the ships the order had been given to beat to quarters and their boats were towing astern.

Pigot ordered the prearranged signal to be made to the other ships for them to cast off their boats. Those of the Hermione went ahead, with the launch commanded by Lt Reed leading and the rest followed on astern. Once again Reed, the Hernuone’s Second Lieutenant, was commanding an expedition, instead of Harris, the First Lieutenant. This appears an insignificant point; but in fact Reed was Pigot’s favourite from the Success, while Harris was not.

Reed steered the launch for the shore until he judged he was only a few hundred yards from the beach and then turned to starboard to run down parallel with it until he found the anchorage. Meanwhile Captain Pigot, knowing the speed the boats would be able to row and allowing for the fact that the current against them would be weaker close inshore, where the water was shallower, ordered the squadron to proceed under easy sail so that he could keep level with the boats but a mile to seaward.

The next half-hour was a tense period for Pigot: it was so dark that he could not see the boats as they crawled along under muffled oars, playing their dangerous game of follow-my-leader. He had planned the attack, brought the ships to the prearranged position, and sent the boats off into the night: now he was entirely dependent on the men in those boats. Supposing the master-at-arms in one of the other ships had been slack in checking that none of the men had been drinking—a shout or laugh from a drunken seaman in one of the boats would raise the alarm. So would any noise if two boats collided, or one of them ran on to a rock. A chance encounter with a native fishing craft might result in the boarding parties mistaking it for a French guard boat… Any one of these eventualities would rob him of a cutting-out expedition’s most effective weapon, surprise.

The squadron had run almost exactly two miles and, according to Pigot’s reckoning, should have been abreast of the privateer’s anchorage. Suddenly he saw a scattering of sparks, then several red flashes, as if huge furnace doors were being hurriedly opened and shut. A few moments later the faint popping of muskets echoed across the water, followed by the dull, booming overtones of heavy cannon, as the French 32-pounders opened fire. A few spurts of water, just discernible in the darkness, showed that the cannon were firing at the ships of the squadron, although the musket fire was clearly aimed at the cutting-out parties.

Pigot promptly ordered the Hermione’s guns to fire back at the French batteries and, as he had previously instructed, the guns of the rest of the squadron joined in. Their shot were unlikely to do the French any harm; but the tremendous ripple of flashes as they fired their broadsides would show the French that five warships were in the offing and might persuade them that, whatever the boats close to the beach were doing, the heaviest attack would develop from the warships offshore.

Soon Pigot discovered that the cutting-out expedition had taken the French completely by surprise: that by the time the enemy had spotted the boats and opened fire with muskets the boarding parties were already ‘in possession of many of the vessels and had one actually under way’.

‘At about four o’clock’, he wrote to Sir Hyde, ‘the vessels were all in possession of our people and standing out with the land breeze, except two small row boats which were hauled up on the beach and could not be got off. And’, he added, ‘it is with particular satisfaction that it has been executed without a man being hurt.’

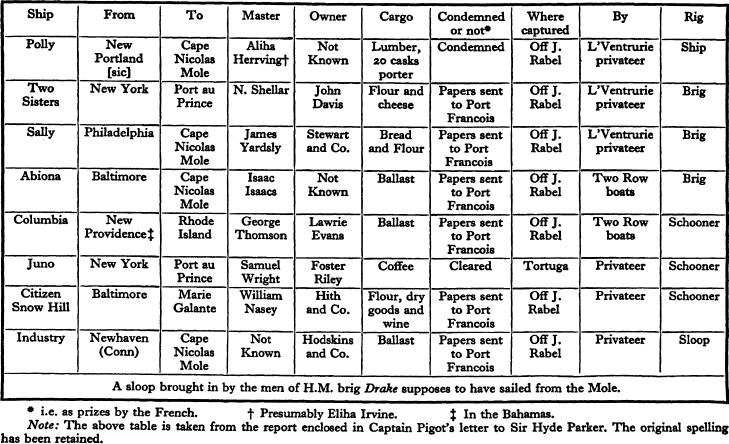

Soon after daylight a convoy of nine ships (including eight American merchantmen) was under way for the Mole, escorted by Pigot’s little squadron. The names, home ports, destinations and cargoes throw an interesting light on the kind of trade being carried out, and the complete details which Pigot enclosed in his report to Sir Hyde are given as Table II opposite.

TABLE II