STEWARD JONES had been mindful of Nash’s instructions the previous night that next day he was to ‘attend the gentlemen and get dinner’, which was the midday meal. He had told Perrett, the tearful and reluctant butcher, to kill a goat, and Holford, the former Captain’s cook, had prepared it.

But the violent debate over whether or not Southcott, Casey and the other two men should be killed, had delayed the meal. Finally three leading mutineers—James Farrel, Bell, and John Elliot—who were now styling themselves ‘lieutenants’, decided that Jones should serve their meal on the quarterdeck under the awning.

They also decided to invite—perhaps order would be a more appropriate word—Mr Southcott to join them. He was brought up and seated at their table for a meal of fried goat’s meat. He was not a willing guest—perhaps he found it a bizarre experience to be dining a few feet from where, an hour earlier, his hosts had called for a show of hands to decide whether he lived or died. Questioned about the meal later he declared, ‘I was forced upon to eat with them’.

In the afternoon all the men on board were ordered aft again: the surgeon’s mate, Lawrence Cronin, had been busy once more with pen and paper. He had realized that most of the mutineers when they reached La Guaira would eventually go to sea again in Spanish or neutral ships, either to earn a living or because they wanted to get to America. With more than 150 men scattering to the four winds, the main danger of any of them being captured by the British and hanged as mutineers would come from them gossiping, bragging in their cups, or informing on each other. The British Government was certain to offer large cash rewards for information leading to arrests. To ensure the identity of the mutineers stayed a secret forever, Cronin had drawn up a special oath which he proposed administering to every man in the ship.

It may seem strange that he should expect men to keep an oath who had just mutinied, committed a series of extremely brutal murders, and were adding treason to the list; but his reasoning was perfectly sound. The British seaman of the period might be reckless with his money on shore—if he was given the chance; it might be impossible to leave liquor within his reach and expect him to stay sober; he might under pressure admit to having a wife in more than one port. He was, however, extremely superstitious and, more important, usually set great store by an oath. Once he took it, he generally regarded it as absolutely binding.

With the ship’s company assembled on the quarterdeck (South-cott, Casey, Price and Searle were also brought up to take part) Cronin administered his oath: they had to swear ‘Not to know one another in any part of the globe, man or boy, if they should meet, nor call each other by their former names’, and they had to declare ‘This is my oath and obligation, so help me God’.

The maintopman John Brown noticed that ‘some were willing and some were not’, but it made no difference: everyone had to take it. To make sure of the four officers, Cronin administered the oath to each of them separately, and Southcott later declared he had no option because they said they would save his life only if he promised ‘not to discover the mutiny at any part of the world’. They did not realize that in law an oath taken under duress was not binding; not worth the breath expended in reciting it.

As night fell, with the Hermione’s bow wave creaming up in the darkness and her sails bellying, the mutineers relaxed once more: the wind was still north, and southward lay the Spanish Main: with a fair wind they were steering, so they thought, for liberty. Astern lay the sadistic oppression of men like Pigot: also behind them—so Cronin no doubt persuaded them—was the tyranny of a corrupt monarchy apparently in the last stages of decay. As a Republican he had probably described the freedom that was to be theirs—while the ship sailed for asylum in La Guaira, an outport belonging to a nation which made no pretence of being democratic and was ridden and ruined by a highly-centralized, corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy presided over by His Most Christian Majesty Carlos IV, who had, in all but title, abdicated his absolute powers to Manuel Godoy, a man more than suspected of being the Queen’s lover and who basked under the absurd title of Prince of Peace.

But for the moment the mutineers could dream: free of the threat of the cat-o’-nine-tails, and with gallons of free wine and rum at hand and no discipline, there was plenty of time to drink and brag. Freedom and potent liquor transmuted their sordid and vicious murders into glorious blows which they had struck for liberty.

There were plenty of men to brag, and much for them to brag about. Young James Allen was proud of the ring he had stolen from his late master, Lt Douglas, and of the boots he had acquired. He related to anyone who would listen how he ‘had a chop’ at Lt Douglas, and how he had found him hiding under the Marine officer’s cot. The boy Hayes boasted how he had had his master, the Surgeon, put to death. The foretopman James Duncan who had claimed that he was lame, said in Southcott’s hearing that, ‘If the buggers were living—meaning the officers—that he should never have had his toe well’.

The mutineers finally decided to liven up the evening with some music, and Steward Jones was the man they wanted to provide it. ‘They ordered me up to play the flute for them, that they might dance on the quarterdeck,’ he reported later.

He sat on the capstan and while his nimble fingers picked out their favourite tunes he watched the dancers and the drinkers and stored up their names and activities in his memory. There was John Watson, for instance, one of the Gunner’s crew, who had claimed to be blind at night. Jones noted that now Watson was ‘dancing with the people, very much in liquor.… He seemed to me to be always stupid with liquor.’ Southcott was able to explain Watson’s apparently miraculous cure because he heard him say ‘I was not blind then: they [the officers] thought I was blind, but they were mistaken’.

Southcott added that ‘He spoke it to let me know that nothing was the matter with him at the time. Some of the mutineers made answer that the mutiny had cured the blind and the lame: nobody was blind at that time: they were all well.’

Another man cheerful and drinking his fill was William Crawley, who had killed Midshipman Smith—described as ‘a little boy’ by Steward Jones when telling how he heard Crawley ‘make his brags about it several times’.

So the mutineers danced, sang and drank the night away. They were men of little or no education, and most of them completely unsophisticated and naïve. They thought they had achieved their liberation, little realizing that most of them would live the rest of their days in terror of a tap on the shoulder, a knock on the door, or the sight of a familiar face in a strange ship or in a strange street. Yet a tap on the shoulder, or a familiar face, was to bring many of them the ‘one-gun salute’ signalling an execution as long as ten years later.

But however sophisticated and educated the men might have been, it would have been hard for them to accept that, whatever the conditions had been in the Hermione, the hard fact was that Britain was fighting, and fighting alone, a desperate struggle against the French. The Revolution in France had started with fine words and loudly expressed hopes of liberty, brotherhood and equality; but it had soon become a tyranny where its leaders, still crying freedom as they set up more guillotines, sought to enslave the world: already it was a tyranny stretching from San Domingo—now several leagues astern of the frigate—to India; and, within a year or two, from Spain to the burning sands of Egypt and the ancient cities of the Levant; from the shores of the Channel, in sight of the Dover cliffs, to the very gates of Moscow.

When one small nation—for Britain, in manpower, was small—had to fight such a massive power (and Britain was the only nation that fought consistently from the beginning of the war in 1793 until its end in 1815, for the peace of 1802–3 was only a breathing space for both sides) it was inevitable that occasionally a wretched series of circumstances should place a man like Pigot under a Commander-in-Chief like Parker in a place like the West Indies.

One can understand and sympathize with the majority of the men for the terrible predicament in which they found themselves; but by venting their sense of injustice on Pigot and nine other men who were comparatively or completely innocent, they had gone too far for any man’s hand to help them—least of all, as they were soon to discover, a Spaniard’s. Even when all excuses have been made, the fact is that in ridding themselves of a tyrant they had made themselves tyrants and immediately established a far worse tyranny. The revolution they had staged in the Hermione was, ironically, a microcosm of the French Revolution; a venture which began with high hopes, but fell victim to man’s greed, jealousy and moral weaknesses: the all too familiar shortcomings which only fools and vote-catching politicians can ignore when planning a better world.

However, the mutineers stand condemned for the senselessness of the murders. Pigot might have been a brute—but Martin was killed only because Redman lusted after his wife. Midshipman Smith might have been a spiteful little sneak—but what justification was there for throwing a dying Lt McIntosh over the side? Lt Douglas might have been a captain’s toady—that was no excuse for the senseless slaughter of Foreshaw, Sansum, Pacey and Manning.

Only two put up a real fight, Pigot and Foreshaw. But even before they had been tossed over the side the mutineers had control of the ship, so it was not necessary to kill anyone to ensure the mutiny’s success. Yet eight more men were killed, and every one of them in cold blood. Was it because ‘dead men tell no tales’? No, since the leaders allowed four other officers to be reprieved, and clearly all four would tell a lot of tales the moment they had the opportunity. Why were the officers not put off in one of the ship’s boats and allowed to row to an island—as the Bounty mutineers had served Captain Bligh and eighteen loyal men? Alternatively they could have been allowed to live and, like Casey, Southcott, Searle and Price, handed over to the Spanish as prisoners of war when the ship arrived at La Guaira.

The mutineers would not have greatly increased the chances of being captured by showing mercy, since the identity of most of the men would be discovered from previous muster books, and they could be identified in a court by such people as John Forbes, now in the Diligence, and Lt Harris. In any case the Admiralty, knowing most men had their price, would soon find a former mutineer willing to turn King’s Evidence in return for a free pardon.

Why then, since the men all knew of the Bounty mutiny, did they kill ten of the Hermione’s officers? The Bounty mutiny had happened ten years earlier; but the mutiny in the little Maria Antoinette, when her captain and another officer had been thrown over the side, had occurred only a few score miles away and only a few weeks earlier: perhaps the methods used were fresher in their minds. But more important is the fact that Pigot’s behaviour had made the men revert to the law of the jungle.

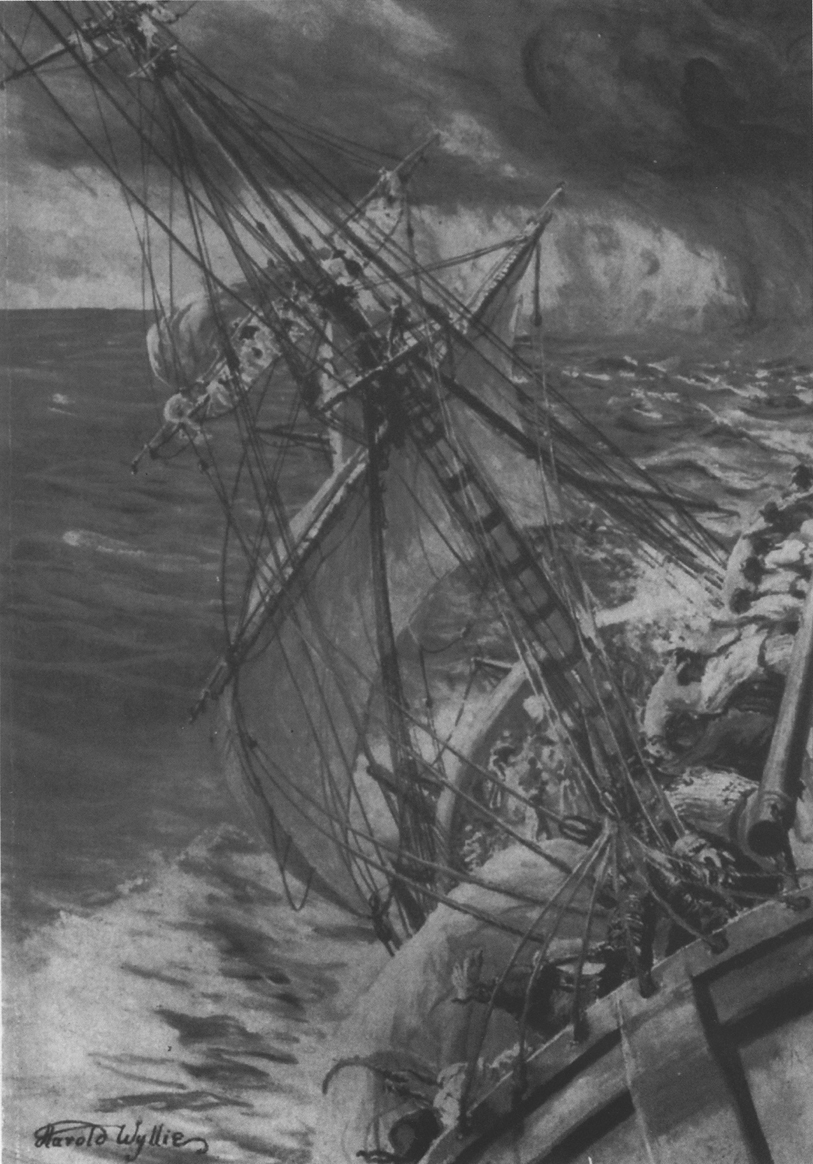

1 A sudden squall: a view from the Hermione’s maintop as men hurriedly reef and furl. On the foremast the midshipman stands in the foretop shouting orders to men furling the topsail just above him. From a copyright oil painting by Lt Col Harold Wyllie, OBE., specially commissioned for this book

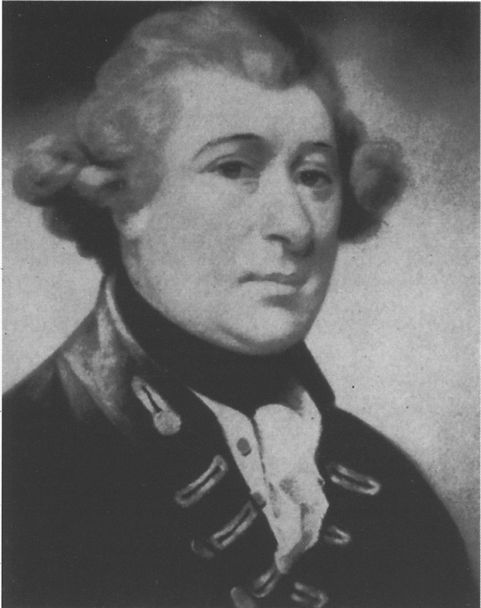

2 Vice-Admiral Sir Hyde Parker: faced with mutiny he advocated ‘imposing discipline by the terror of punishment in this momentary crisis…’

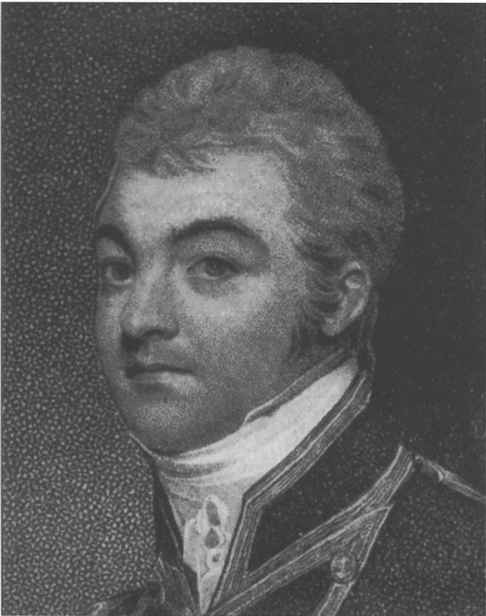

3 Captain Sir Edward Hamilton, who commanded the frigate Surprise in one of the most daring cutting-out expeditions in the Navy’s history and recaptured the Hermione.

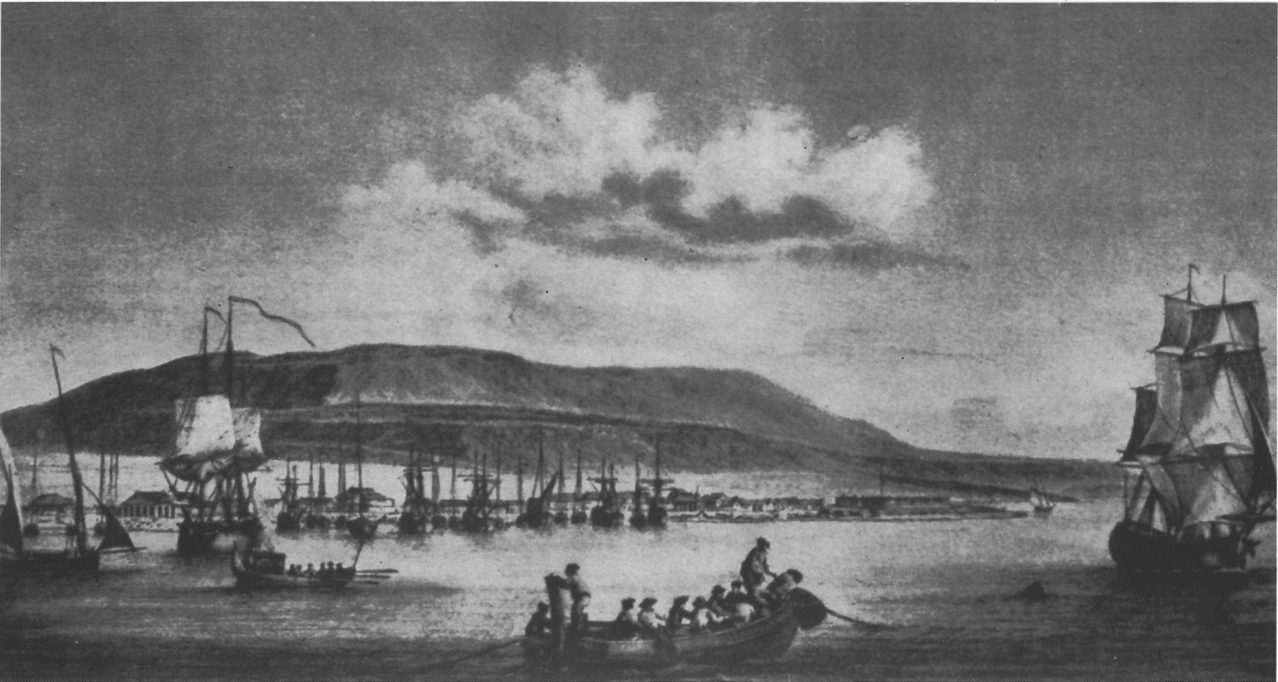

4 Cape Nicolas Mole about the time of the mutiny: it was from here that the Hermione sailed on her last voyage under her original name.

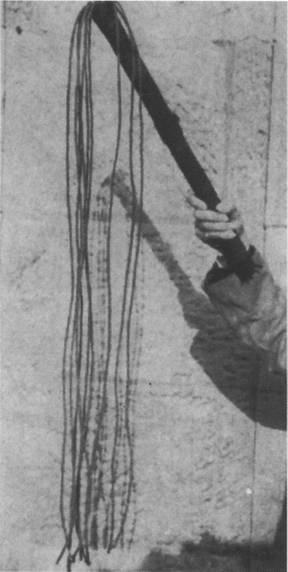

5 A cat-o’-nine-tails used to flog a man on board HMS Malacca in 1867.

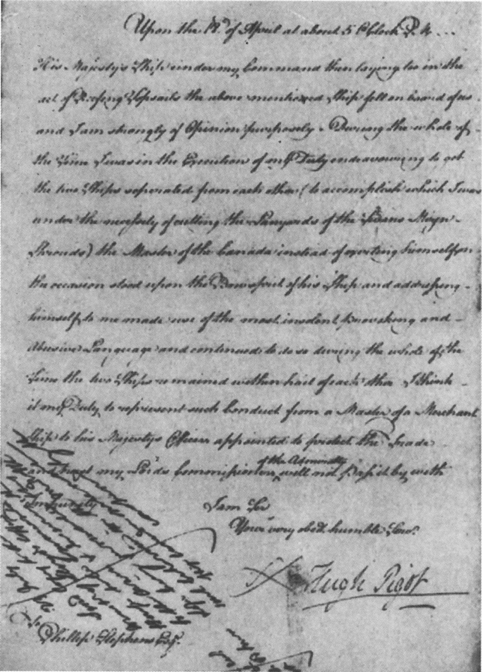

6 A letter written by Hugh Pigot within a few weeks of getting his first command, complaining to the Admiralty that a merchant ship deliberately collided with his sloop the Swan.

7 An extract from Sir Hyde Parker’s journal recording how he received first new of the mutiny in the Hermione.

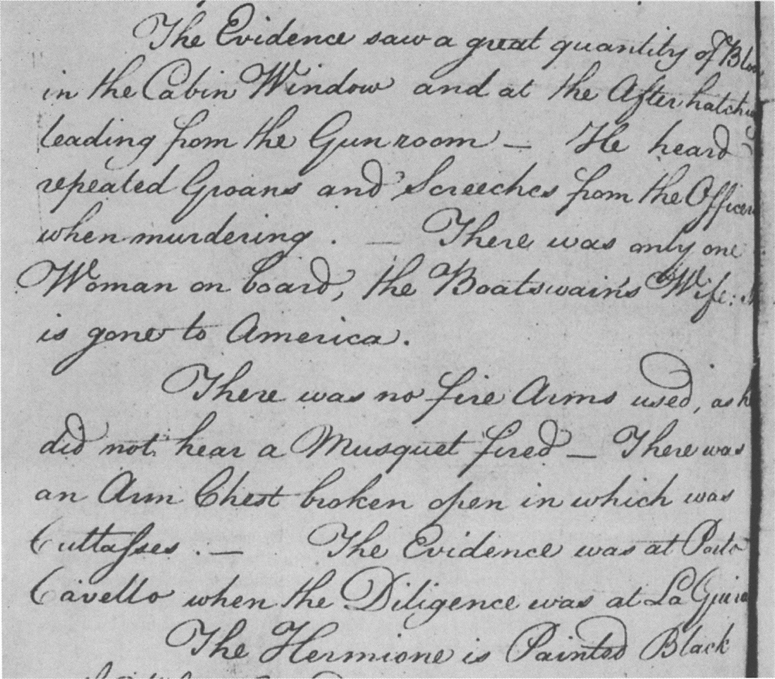

8 An eyewitness description of the mutiny: part of the original deposition by John Mason, a carpenter’s mate in the Hermione.

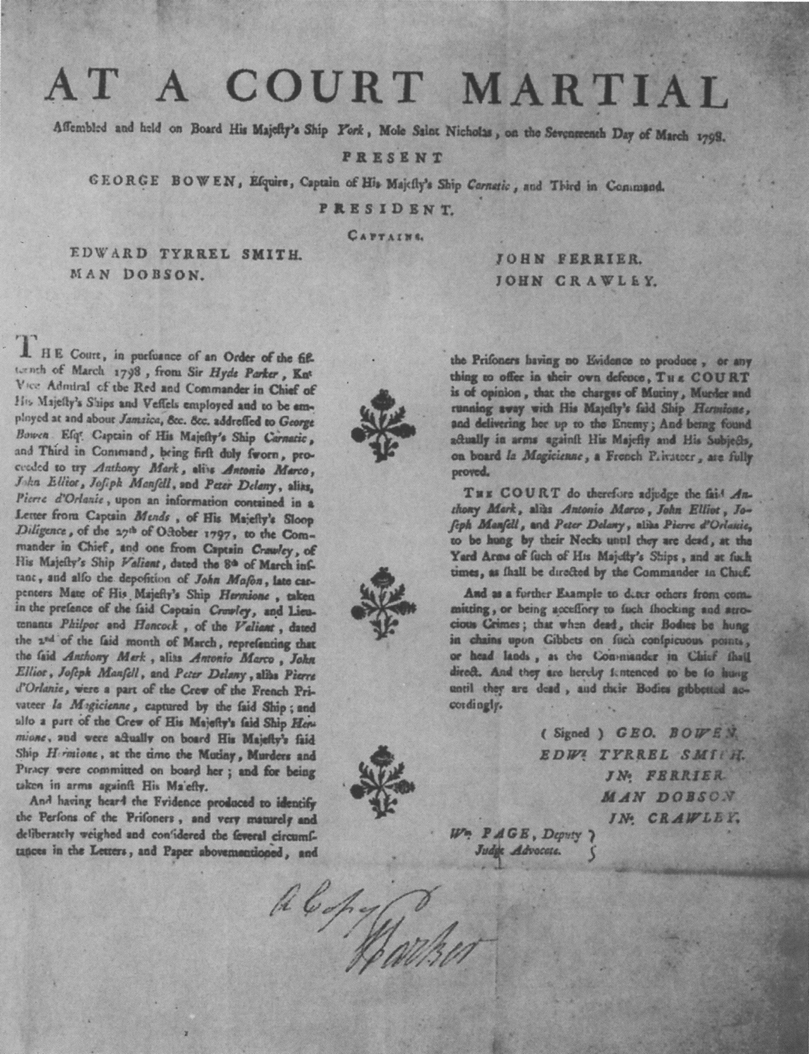

9 A grim warning: one of the posters printed for circulation throughout the Caribbean and American east coast seaports, giving the judgment of a court martial which tried four Hermione mutineers — an Englishman, two Italians and a Frenchman — and sentenced them to death. This photograph shows an original poster sent by Vice-Admiral Sir Hyde Parker to the Admiralty, and his signature appears at the bottom.

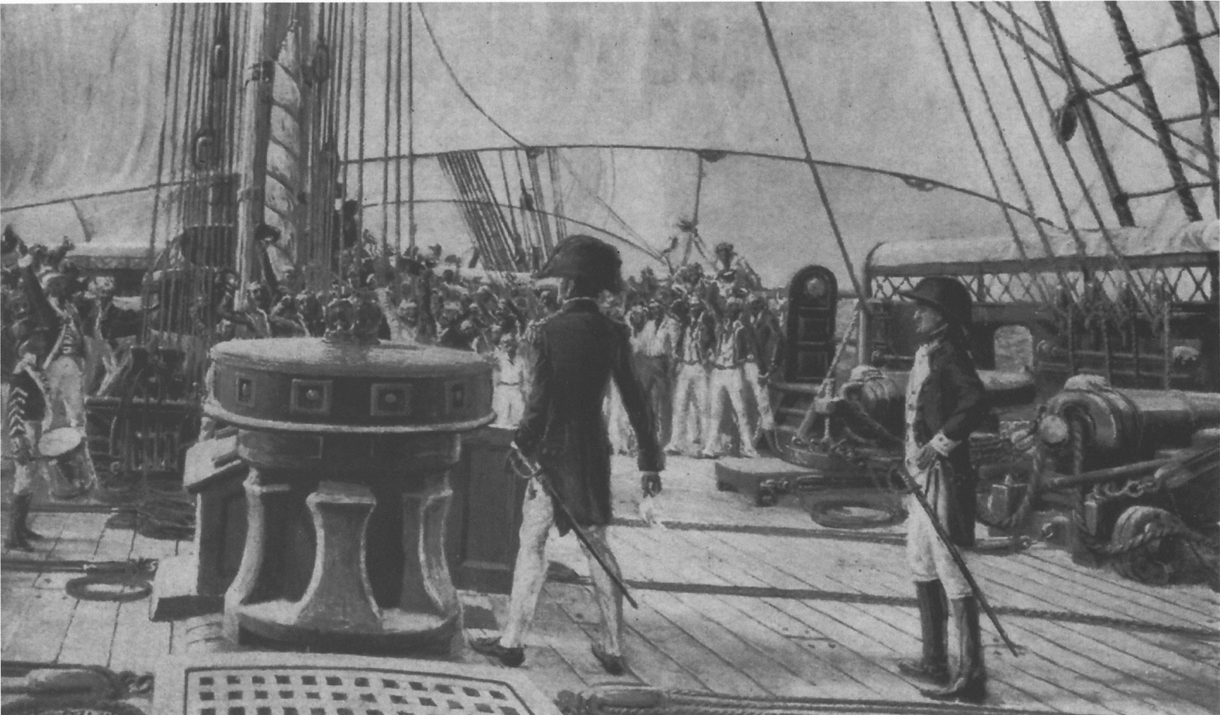

10 ‘I turned the hands up to acquaint the officers and ship’s company of my intentions to lead them to the attack.’ The men of the Surprise cheer Captain Hamilton as he tells them of his plan to recapture the Hermione. From a copyright oil painting by Lt Col Harold Wyllie, OBE, specially commissioned for this book.

11 A hundred men from the Surprise capture the Hermione in Puerto Cabello harbour and get her out to sea while under fire from 200 guns. More than 350 Spaniards are still on board.

On Saturday, September 23, the second day after the mutiny, the Hermione’s new ‘captain’, William Turner, was far from sure of the ship’s position, so the mutineers decided Mr Southcott should be made to take some sights. They went down to the Captain’s cabin ‘to desire me to go on deck to take an observation. I went on deck carrying my quadrant, and after that Redman came down twice or three times into the cabin with Turner.’ They worked out the sights, put Southcott’s charts on the table, and laid off a new course for La Guaira, allowing for the current which flowed up from the southwards along the South American coast into the Caribbean and was sweeping the Hermione some sixteen miles to the westward every twenty-four hours.

From time to time when Turner and the ‘lieutenants’ wanted to talk together in secret they used the Captain’s cabin, ordering the guards to take Southcott and Casey for a walk on the quarterdeck. At one meeting they had to decide what to do with the officers’ possessions: they had collected and locked away a considerable quantity of loot. Captain Pigot’s tableware alone made a sizeable list—apart from fifty silver spoons of various types, there were such items as a couple of silver porter mugs, the silver teapot given to him by Captain Otway after the Ceres grounding, and a silver cruet. There were also two pairs of silver shoe buckles and a pair of knee buckles, two watches (one in gold, another pinchbeck), a pair of silver-mounted pistols, a gold ring and eighty dollars in cash.

A search through the possessions of the other officers, both murdered and prisoners, yielded 368 dollars, three more watches, and a quantity of clothing. The ‘lieutenants’ decided to dispose of the clothing (after taking for themselves the more luxurious items like silk shirts and stockings) by dividing them up between the messes, of which there were more than twenty-five in the frigate, each comprising six or more men.

The crew were once again ordered aft to the quarterdeck, watched this time by Casey and Southcott. They got all the Captain’s clothing and placed [it] on the deck and shared [it] out,’ Casey said later. ‘They then fetched the officers’ chests and overhauled them for papers.’

But the silver, watches and other valuables, the leaders decided, should be shared out among those who had taken major parts in the mutiny. The articles would be made up into roughly equal shares, and given to the men who, according to John Holford, ‘entered their names for that purpose’. The articles were heaped on and round the capstan—a silver gravy spoon, five watches, silver porter mugs, twenty-three tablespoons, a gold pencil case, a silver teapot…

The money was made up into piles each of sixteen dollars, and Turner prepared for the share out, doing it in the usual seaman’s way. ‘I saw Redman have a list in his hand from which the names were called… and I thought it was a list of the principal persons concerned in the mutiny,’ said Jones. According to John Holford, it was Turner who held up an article and called out to William Anderson, the gunroom steward, ‘Who shall have this?’, and Anderson who was facing the other way, read out a name. ‘Those so named,’ Holford said, ‘were the principal mutineers.’

Nash, Leech, Joe Montell, Smith, Marsh and Elliott were among those who each had sixteen dollars, while those receiving individual articles included Jay, Forester and Redman. But the share out did not satisfy everyone. ‘Thomas Jay… claimed a silver teapot which had been Captain Otway’s present, saying he thought he deserved it,’ recorded Steward Jones. When Forester, who had certainly helped to kill seven of the ten officers, (Southcott later testified that ‘I heard him say he had assisted to murder the whole of the officers’) came away from the capstan Jones noticed he had ‘two or three silver spoons in his hand, and some gold’. He was far from happy and was ‘disputing with Croaker, the Gunner’s Mate, about the share of the prize-money, that he had not received what he deserved, as he thought he was a principal in the murders or massacres’.

Sartorially the mutiny had brought about a great change in the ship’s company. David Forester had some of the Captain’s clothing: Southcott noted he was wearing one of Pigot’s shirts, while Jones, previously responsible for the Captain’s laundry and who knew every item in the wardrobe, saw that Forester was also wearing a pair of Pigot’s white stockings.

Young Allen added one of Lt Douglas’s shirts to his kit which, of course, already included the pair of cut-down half-boots; and Redman was still rigged out in the white ruffed shirt and white waistcoat in which he had left Mrs Martin’s cabin. Undoubtedly clothes made the man, for Jones reckoned that Redman ‘seemed to act like an officer’.

As the Hermione approached La Guaira the men began making preparations for going on shore: for many of them—particularly the gunroom steward William Anderson, the ship’s cook William Moncrieff, and an American seaman, Isaac Jackson, from Boston—it would mean leaving a ship which had been their home for nearly five years. They would have to take all their belongings with them—clothing, blankets, hammocks (each man had two) and any other prize possessions or loot they had accumulated. Many of them needed new bags to carry their gear, so John Slushing, now acting as sailmaker in place of John Phillips, who had more important work, fetched up some rolls of canvas from the sailmaker’s store and issued out lengths to anyone who wanted them.

Once the men went on shore from the Hermione they would of course begin a new life: Lawrence Cronin’s oath would start to operate. The Hermione’s previous muster book would give Sir Hyde Parker the identities of most of them because every captain had ‘at the expiration of every two months, to send to the Navy Board a full and perfect muster book…’ This contained (or should—some captains and pursers were lax) many details about each man in the ship. Except for officers, it was supposed to state the man’s name, place of birth, age and rating.

The last muster book sent in by Pigot was for the period ending July 7, 1797, but unfortunately for Sir Hyde it had by then been forwarded to the Admiralty, and until he could get it sent back again it was no help. The one then on board, beginning July 14, should have been sent in on September 14, but of course the Hermione was at sea. Sir Hyde would therefore eventually know the names of everyone in the ship up to July 7, but not those who had joined after then (the former prisoners that Pigot had taken out of the cartel, for instance) or had left the ship.

Clearly every mutineer in the Hermione would have to change his name—even those who had joined after July 7, since their real names were known to Forbes in the Diligence, and to the four officers. The leaders had already anticipated all this: the muster book must be destroyed, but since the Spanish authorities would want to know of everyone in the ship, a list giving their new names would have to be drawn up.

The task was given to Redman, who went down to the Captain’s cabin, ordered Southcott and Casey to be taken out, and sat himself at Pigot’s bureau with pen, ink and paper. Every man in the

ship—with the exception of the four prisoners—was sent down to him one after the other and asked what name he wanted to adopt. Thomas Nash favoured Nathan Robbins for himself, while the unpredictable Thomas Leech went back to the name he had adopted when he deserted from the Success, Daniel White. The Dane Hadrian Poulson became Adiel Powelson while the murderous David Forester chose Thomas Williams as his alias. The Frenchman Pierre D’Orlanie became Peter Delaney and the Surgeon’s servant James Hayes changed his name to Thomas Wood.

One of the men who made the least change in his name was Richard Redman: he merely became John Redman.

Lawrence Cronin, the self-avowed Republican, then took over the pen and paper: the mutineers would need a letter or petition to present to the Spanish Governor explaining why they had been forced to mutiny, and why they had brought the ship to a Spanish port.