The turn of the decade was the last time for many years to come that British speedway was able to begin a new season in fully confident mood. The number of tracks increased yet again to thirty-four overall. Although Bristol’s Knowle Stadium was still under-developed compared to most of the other Division One stadia, a second successive Division Two championship meant that the Bulldogs could not reasonably be denied promotion.

Although promotion continued to be a major issue, with upgrading by no means automatic, four Division Three sides, champions Hanley, runners-up Yarmouth, Halifax and Plymouth – a good geographical spread – moved from the third tier to the second to produce what would now be a thriving fifteen-team division.

The promotions significantly reduced the size of Division Three, which lost Hastings – the victim of anti-noise campaigners – and gained Cornish track St Austell. With ten members it was still a healthy league and an expansionist Control Board granted probationary licences to Long Eaton, Motherwell and Wolverhampton for an initial season of challenge matches, prior to joining a league.

The Control Board granted licences for new tracks to run a probationary season before entering the National League. Long Eaton, here in action against Exeter, operated for the first time since 1930.

With the World Championship restored and a home Test series against Australia an established part of the fixture list, speedway had every right to feel generally optimistic, notwithstanding the failure, despite a massive campaign of political lobbying, to win a reduction in entertainment tax. The sport’s general optimism reflected the mood in the country as a whole. The Second World War was becoming increasingly distant, although the Cold War stand-off with the Communist block was about to burst into real conflict in Korea.

Division Three had from the start been designed as a training ground to provide the riders needed for the sport’s expansion and, hopefully, to nurture the stars of the future. It certainly succeeded in the case of Trevor Redmond (left) of Aldershot and Eric Boothroyd of Tamworth, both of whom were to become Division One heat leaders and internationals, with Wembley and New Zealand and Birmingham and England respectively.

Essentially, God was in his heaven, the Lions and Sir Arthur Elvin (knighted for his role in the 1948 Olympics) were at Wembley, Jack Parker was still drawing his match race championship ‘pension’ and Johnnie Hoskins, after severing his connection with Bradford, was enlivening the Scottish scene with highland flings on the centre green at Glasgow Ashfield.

The first couple of years of the 1950s were essentially the time when speedway was able to catch its breath and enjoy a period of relative stability after the mercurial expansion of the late 1940s, which saw the number of tracks, with the probationary clubs included, treble. Although enthusiasm was still high, and speedway was still expanding, some of the frenzy apparent in the 1940s – the rather cynical and anti-speedway Daily Express sports columnist John Macadam termed it ‘hysteria’ – had disappeared.

Wimbledon, rock bottom of Division One in 1949, climbed to third place in 1950 as promoter Ronnie Greene began the team-building that would bring the Dons dominance later in the decade. A key signing at Plough Lane was seventeen-year-old Ronnie Moore, pictured using team-mate Norman Parker’s machine as a convenient resting place.

Speedway was now in evolutionary rather than revolutionary mood. Changes were sufficient to encourage those impatient for progress in areas such as promotion and relegation, yet subtle enough not to alienate older fans. Most people believed, in principle, in promotion. Division One promoters in London were not so sure about relegation. With the wooden spoon going to London clubs in four out of the first five post-war seasons – West Ham (1946), Harringay (1947), Wimbledon (1949) and Harringay again in 1950 – capital city managements had some justification for their doubts.

Capturing the feel of post-war speedway at its most intense and atmospheric, with a packed main stand, home straight terrace and pits area at Brough Park, Newcastle. It is difficult to believe that within a couple of years Newcastle had closed its doors.

A massive turnaround for Oxford. Bottom of Division Three in the club’s debut season of 1949, in 1950 the Cheetahs won the title, despite early injury problems. Back row, left to right: Pat Clarke, Eric Irons, Ernie Rawlings, Bill Kemp and Harry Saunders. Front row: Frank Boyle, Jimmy Wright, Buster Brown and Bob McFarlane.

For the first three post-war seasons the Division One rankings in the Stenners Annual consisted exclusively of men with pre-war experience. When the 1950 annual was published the rankings, based on 1949 performances, were divided equally between old and new generations.

During the 1950 campaign, the spoils continued to be shared. The big difference lay within the rankings, where Graham Warren overtook the likes of Parker, Price and Lamoreaux to head the table. Louis Lawson’s third place in the 1949 World Final gave the Belle Vue rider a significant step up and the international success enjoyed by his team-mate Dent Oliver and by Australian Jack Biggs of Harringay also won recognition.

The flourishing Division Two began to produce men who brushed aside the supposed gap between the leagues, through outstanding performances in Test matches, the World Championship and other competitions.

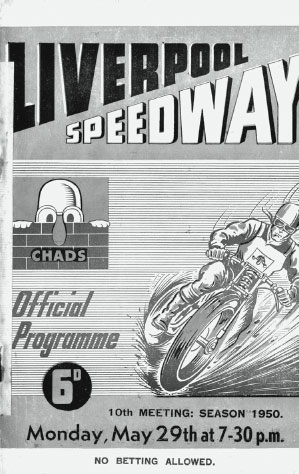

In the post-war era, World Championship qualifiers often attracted the biggest crowd of the season in the lower divisions. This line-up at Division Three Liverpool includes Division One riders like Malcolm Craven of West Ham and Ron How of Harringay.

Liverpool mascot Mr Chad found plenty to look at when he peered over the wall at Stanley Stadium, including the longest track, at 446 yards, in British speedway.

England won the 1950 Tests against Australia by three matches to two, after fairly radical changes to the line-up following a not-too-convincing opening to the rubber. Australia, faced with the familiar problem of a restricted base of riders from which to choose, had little option but to use Division Two men and no fewer than eight from the second tier gained Test recognition during the series. Australia launched the series with a convincing 60–47 victory at West Ham. Tommy Price, a series ever-present and a consistent performer headed the England scorers. Although Jack Parker, Cyril Roger, and Eric French all made contributions, it was not enough to halt an Australian side in which high scores from the established Aub Lawson, Vic Duggan and Bill Longley were supported by 11 points from Division Two’s Ken Le Breton and 7 points from reserve Jack Young, also a second-tier rider with Edinburgh.

Harringay finished bottom of Division One in 1950. Danny Dunton (centre), tipped at the start of the season as ‘a future flyer’, qualified for the World Final and was third highest scorer for the Racers. Team-mate Split Waterman, in his first season since moving to Green Lanes from Wembley, experienced injury problems and was a disappointing seventh in the World Final.

The benchmark for any aspiring young rider was still to beat Jack Parker, a legend in his own lifetime. Ron Mountford of Birmingham (left) attempts to pass Parker and enhance his own reputation.

England won the Test series 3–2 against Australia in 1950. On home ground at New Cross the Roger brothers Bert and Cyril inspired a 63–45 home victory with 14 points apiece. England’s team was, back row, left to right: Tommy Barnett of Wembley (trainer), Cyril Roger, Cyril Brine, Norman Parker, Tommy Price. Front row: Bert Roger, Eric French, Alan Hunt and Louis Lawson.

England levelled the series with a 58–50 win at Belle Vue. Home rider Louis Lawson was top scorer with 14 points but Aces team-mate Jack Parker was subdued. For the third Test, at New Cross, the England selectors made radical changes, dropping Jack Parker as captain in favour of his brother Norman. They also brought in Cyril Brine, like Norman Parker a Wimbledon rider, promoted home rider Bert Roger into the team proper and took a leaf out of the Australian book by dipping down into Division Two and naming Alan Hunt of Cradley Heath as reserve.

England won the New Cross Test 63–45 to take a series lead, the Roger brothers Bert and Cyril scored 14 points apiece and Hunt weighed in with 7. The Australian selectors also made changes, dropping Merv Harding, a great success in the Belle Vue match, and Jack Young, on the grounds that neither had previously ridden the tricky New Cross track.

Hunt was promoted into a full team spot as the scene shifted to Wimbledon for the fourth Test, and finished as the second highest scorer with 12 to Cyril Brine’s 13. England’s 62–46 victory clinched the series. The final Test at Wembley, won 55–53 by Australia with top performances by Warren and Le Breton, was an anti-climax in terms of the rubber. Brine with 16 points and Tommy Price with 15 were the England top scorers. Jack Parker was recalled for the match but managed only 2 points – the same disappointing score as brother Norman.

When the spotlight turned to the World Championship, there was more success for Division Two. Ken Le Breton had become the first rider from the second tier to qualify for a World Final in 1949, fighting his way through from the first round. In 1950 Jack Young achieved even greater success, finishing as top scorer in the championship round, the last leg before Wembley itself, ahead of Warren, Brine, Jack Parker, and Aub Lawson. At the final itself he recorded a heat win over fellow countrymen Jack Biggs and the admittedly fading Duggan.

Although the pre-war World Championship had failed to produce a British winner, the second post-war final again saw a home success. The emphasis had to be on a Briton as the winner, Freddie Williams of Wembley, was a proud Welshman. Wally Green of West Ham was second, completing a one-two of unfancied contenders. Warren was third, a last lap all-out attempt to beat Williams in heat ten proving fatal.

There was no silverware at Custom House in 1950 but plenty of laughs. Malcolm Craven (left) seems to appreciate the unusual headgear of Lloyd ‘Cowboy’ Goffe, who joined the Hammers in 1950 from Harringay.

Hanging on to his second place at that stage of the meeting would have subsequently given the Australian the chance to contest a decider with the Welshman. Settling for second best was not Warren’s style and in the days of a one-off final, such split second decisions meant the difference between success and failure.

Wimbledon promoter Ronnie Greene staged speedway in 1950 at Dublin’s premier greyhound venue, Shelbourne Park, using Dons’ riders. In 1951 he imported a team of Americans to race as the Shelbourne Tigers. Pictured in the Shelbourne pits in 1950 are, from left to right, Dons Mike Erskine, Cyril Brine, American Ernie Roccio and Jim Gregory. Roccio was killed at West Ham in July 1952.

Wembley switched managers, with Duncan King taking over on the retirement of long-serving Alec Jackson, but the relentless pursuit of success that exemplified the Empire Stadium approach did not slacken. Sir Arthur Elvin demanded that his team should not only succeed but should win with style and his insistence on the first rate filtered right through the ranks of Wembley employees. It was reputed that even the rakes used for grading the track were required to stand at attention when not required.

The Lions duly won Division One again in 1950, no doubt to the relief of manager King, who was to be judged by the highest standards. He proved more than up to the task, with one of his crucial team-building decisions proving a key factor.

Wembley appeared to be in trouble in July, when they lost Tommy Price through injury and Bill Gilbert through illness. The indifferent form of both Bill Kitchen and George Wilks also threatened the Lions’ hold on the title. King established his managerial credentials by signing Bob Oakley from Southampton. Oakley averaged more than 6 points a match, and provided a solid backbone for the denuded side, along with Freddie and Eric Williams.

When Price and Gilbert returned to action the side was strong enough to cruise to the title with a 10-point margin over Belle Vue. Bristol managed a respectable third from bottom in the club’s first season in the top league.

In Division Two, Le Breton, Young and Hunt, already mentioned for their Test match exploits, occupied the top three positions in the rankings. The veterans who had completely dominated the division in the immediate post-war era had disappeared more rapidly than the Parkers and their other top-tier counterparts.

The second tier was producing its own legends, many of whom would go on to be stars in Division One. In the league itself, with previous Division Two high-flyers Birmingham and Bristol now removed from the action through promotion, a new star was born in the east. Norwich was a successful pre-war centre based in a purpose-built stadium and was among the first tracks to reopen once hostilities had finished. Norwich were to become the next focus for the arguments in favour of automatic promotion to Division One, but the Stars’ championship success in 1950 was not enough to secure their elevation to the top flight.

Both Norwich and closest rivals Glasgow White City were unbeatable at home. Disputing the title throughout an exciting season, both teams won four matches on their travels and lost other away fixtures by tantalisingly narrow margins. The factor that produced a 1-point margin in Norwich’s favour at the end of the campaign was the side’s 42–42 draw at promoted Hanley.

Third-placed Cradley also finished just a point behind Norwich and level with White City. The Heathens won more away matches than their rivals, but lost twice at Dudley Wood, to local rivals Coventry and to Plymouth. Both Norwich and White City were convincingly beaten in the Black Country.

The numerical strength of Division Two allowed a football-style fixture list of one match home and one away against each opponent, and the dates this left free were largely filled with regionalised shield competitions, which proved successful in their own right.

Individually, Phil Clarke and Australian Bob Leverenz, another Division Two rider who made senior Test appearances, headed the Norwich scoring charts. Scots discovery Tommy Miller was the key man at White City, while Hunt and Eric Boothroyd, both later to feature in Division One with Birmingham, steered Cradley to third place. Oxford, bottom of Division Three in 1949, raced to the top of the table in 1950, ahead of Poole and Leicester. Former Hammer Pat Clarke was Oxford’s star but he had to give second best in the divisional rankings to Poole’s Ken Middleditch.

Clarke had his revenge in the new Division Three Riders Championship final at Walthamstow, watched by more than 23,000 people. He won all his five races, despite in one heat being led for three laps by Aldershot’s Basil Harris, finishing ahead of New Zealander Trevor Redmond, also of Aldershot, and Middleditch.

Few riders were privileged to have the inside knowledge of Wembley in the 1950s possessed by Lions legend Freddie Williams. Apart from an instinctive feel for the fastest way around the stadium, he had a deep awareness of the pivotal role played within speedway by Wembley chairman and managing director Sir Arthur Elvin.

Born in Port Talbot, South Wales, Freddie Williams was one of the grass-track riders who responded to Wembley’s bid to create an all-British team post-war.

Williams, whose younger brothers Eric and Ian also enjoyed distinguished speedway careers, rode only for Wembley during a career that brought him virtually every available honour. As a grass-tracker, he answered Wembley’s mid-1940s advertisement calling for young men with aspirations to become successful speedway riders. He recalls:

When Elvin was asked to reopen Wembley after the war, he insisted that he would only do it if he could have a team composed of British boys. The advertisement asked for motorcyclists with grass-track experience to try out at Rye House.

Wembley encouraged us, trained us and accepted that it took time to produce a rider to succeed in the hard school of the National League Division One. Elvin’s vision paid off, not just for his own team but for speedway in general.

Freddie Williams made his Lions debut in 1947 and gained a regular place the following year, in a side unsettled by having to ride home matches at Wimbledon while the Olympic Games were staged at Wembley. In 1950 he was established in a team that had regained the Division One title lost to New Cross in 1948. Few, however, forecast the spectacular success waiting around the corner. He won the world crown at Wembley on 21 September, dropping his only point to Jack Parker.

Freddie Williams, despite being part of Wembley’s multi-championship-winning backbone, was probably often under-rated. Williams is pictured chasing Graham Warren at Perry Barr, Birmingham.

Wembley in September 1950 with World Champion Freddie Williams, runner-up Wally Green and third placed Graham Warren. The long-term effects of injury meant the much-fancied Warren was never to come so close to the trophy again.

Although highly respected by fellow riders and appreciated by the fans, Williams was never subject to the phenomenal hype that surrounded many riders in the early 1950s. He was first and foremost a team-man, in a Lions side that won five successive Division One titles. Despite tremendous personal glory – he was runner-up in the World Final in 1952 and secured his second World title in 1953 – his feet were always firmly on the ground. Having experienced the realities of life in industrial South Wales, he never lost a sense of proportion about his speedway stardom.

Winning the World Final brought me £500 at a time when my Dad was probably getting £4.50p a week slaving his guts out in a steelworks.

Although speedway fans were fanatical at times, no-one really jumped up and down and hugged and kissed you when you won things in those days. When I won the titles, it was just a night’s work as far as I was concerned.

Freddie retired midway through the 1956 season, Wembley’s last in the National League. After a particularly difficult race at Belle Vue, he returned to the pits and told Alec Jackson that he had reached the end of the road.

When things are not going well and you are finding racing difficult, that is the time when you are most at danger of hurting yourself. I had a family to consider and I made up my mind there and then that it really was the end of my racing career.

President of the Veteran Dirt Track Riders’ Association in 1981, Freddie returned to the Empire Stadium as team manager when the Lions briefly roared again in 1970/71. Whatever regrets he may occasionally have harboured about his early retirement, he has never regretted his loyalty to his only club.

Wembley was always good to me, loaning bikes when necessary and being very understanding when I was injured grass-tracking. There were many times during my career when I was approached to ride elsewhere but I always said I would stay at Wembley, and I did.