“Investing is fun, exciting and dangerous if you don’t do any work.”

- Peter Lynch

Meet Lucinda, who has just launched Lucinda Lemonade Inc. in the quaint, tidy town of Lemonville.

To open a lemonade stand requires capital — that is, money. Maybe a buck or two here buys the lemons, and one or two there buys the sugar. There’s also a dip into the piggy bank for pitchers, along with crayons and paper for a sign. Rent is not a problem for most lemonade stand owners. The start-up capital – the money required to get going – is minimal.

Let’s assume for the moment that Lucinda’s lemonade stand is doing a brisk business, and she wants to expand her operation, perhaps by setting up a second stand on Main Street. She runs into a small problem in her exciting expansion: she needs more money.

Lucinda considers going to a bank for a loan but worries they would never lend money to her tiny business. She has the idea of raising money from a few friends by selling pieces of this profitable and growing business. If Lucinda decides to sell a piece of the lemonade business, she’s selling stock — or if you want to be particularly highbrow about it, equity. If she divides the business into tenths and sells one-tenth of the business to her neighbor Liam, she’s sold one share of stock.

The process goes something like this: Lucinda sells a piece of the business — that is one share of stock — for $10. Two things are now different. One is that Lucinda’s business has $10 in the piggy bank that it didn’t have before (enough to buy new signs and a table and pay her new assistant). The other is that Liam now owns a piece of the company. That means that he’s entitled to one-tenth of the value of Lucinda’s business going forward, whether that value goes up or down.

Keep in mind that Liam and Lucinda’s deal is a private one. In other words, the share in Lucinda Lemonade was not traded on a stock exchange; instead, Liam and Lucinda negotiated privately since Lucinda Lemonade is still a private (not publicly traded) company. This is known as a private equity deal.

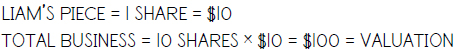

Now let’s turn to Liam, who is Lucinda’s first passive investor. Liam is an investor because he’s risked some money for a slice of the action, and he’s passive because he doesn’t take any day-to-day role in running the business. The closest he comes to being involved with the business is stopping by for a free cup of lemonade; he often feels entitled to do this as a shareholder, someone who owns a share of stock in a company. He has traded $10 for a tenth of the business, which effectively values the business at $100. In fact, we can say the lemonade stand business has ten shares outstanding and a valuation of $100:

There’s no guarantee Liam will get his $10 back. There’s no guarantee he will ever make money on his investment. He might even lose it all.

So why does our investor invest? Because he feels that he will make money — that is, get a return on his investment. A share of a business that does well can become valuable. If Liam owns a share in a successful business, he can do well for himself.

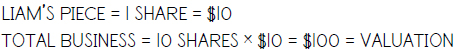

So how will he get this return? Let’s assume that the second lemonade stand really takes off. At some point, $10 will start to look like a small price to pay to own one-tenth of a business that is selling buckets of lemonade. Liam’s neighbor Ella gets wind of their success. She thinks that one-tenth of this dynamic business is worth more than $10. She offers to give Lucinda $11 in exchange for an additional share. Lucinda balks at the offer. After all, she doesn’t need any additional funds at the moment, and she doesn’t feel like selling an additional piece of this growing venture. Every share she sells leaves less for herself. So Ella approaches Liam one day as he sits and tests the product on the stoop of his house. She asks if he would like to sell his share in the lemonade venture to her for $12. Liam thinks about it for a minute, decides he’s sort of sick of the lemonade thing anyway (having already had more lemonade than any person logically should in a lifetime) and realizes that if he sells his share for $12 to Ella, he’s made a quick 20% return on investment (ROI) in the form of a capital gain, an increase in the value of his share:

He takes Ella up on her offer: he gives her the stock certificate he had gotten from Lucinda showing ownership of one share of “Lucinda Lemonade Inc.” In exchange, he gets $12 from Ella and spends it (taxes complicate things, but we’ll get to that later).

Lucinda still needs more cash. She’d love to buy two new manual lemon squeezers to boost her lemonade production. Unwilling to give away additional equity, she decides to borrow money — not from a bank, but from some of the townspeople of Lemonville. Lucinda realizes that by borrowing money from a neighbor, she avoids giving up any ownership in the business. Instead, she is just borrowing some money that she promises to return later. She is thereby issuing a bond, a promise to pay back money borrowed. The disadvantage is that she has to pay back both the interest and principal to the bondholder.

Along comes George, who feels that he would love to lend some money to Lucinda Lemonade Inc. After all, Lucinda offers 5% interest, a decent return with bank saving accounts paying only 1%. George knows that Lucinda is paying four additional percentage points because she’s not as safe, or credit-worthy, as the corner bank. He may lose his investment if Lucinda doesn’t repay her debt. But he likes the idea of getting more interest in exchange for that risk, a risk premium, and he thinks Lucinda Lemonade Inc. is good for the money. George signs a contract with Lucinda, saying that he will lend her $50.00 in exchange for the right to receive $2.50 a year (his interest), and he will get back his initial $50.00 loan, or principal, in five years. George has therefore purchased a bond with a 5% coupon (contractual interest rate) and a term of five years.

“More important than the return on my money is the return of my money.”

- Will Rogers

Both Liam and George so far look like shrewd investors. After all, each has managed to invest some money and get a nice return. But even at lemonade stands, things don’t always turn out peachy.

Any investment involves risk. There is no return without risk.

This leads to Lemonade Law #2:

Even a United States Treasury Bond, which is just a simple loan to the federal government, involves potential risk: the risk that the United States won’t be able to pay the loan back — an unlikely risk, but still a risk. That risk used to look silly to worry about. But with our sky-high debt levels, a U.S. bond default is no longer off the table — unlikely, but not impossible. The Treasury bond is also subject to inflation risk, the risk that the interest payments will be worth much, much less many years from now.

Risk is a difficult concept to quantify or define. Anyone can quantify return. We can calculate it and see it in black and white. Risk is not so simple. How much return did Liam make? That’s easy. You know Liam made a 20% return on his money. But how much risk did Liam take on to earn that 20%? This is harder.

Economists have tried to figure out ways to calculate risk. A Nobel Prize winner named William Sharpe created his Sharpe Ratio, which treats price volatility, or the amount prices zig and zag, as a measure of risk. Unfortunately, no superficial measure of volatility is a truly sound measure of real risk. We won’t bore you with the befuddling details of Sharpe Ratios, Beta, and volatility. We’ll just show you that risk is difficult to calculate, while return is relatively easy. More important: there’s an iron-clad relationship between risk and reward.

This leads to Lemonade Law #3:

Risky investments have a higher potential return but less of a likelihood of that return ever happening. Just as a lottery ticket has huge upside but very low odds, the same goes for any dicey investment.

Imagine that down the street from Lucinda Lemonade Inc. opens a competitor named Meg’s Gourmet Lemonade. Meg saw the success of the lemonade business and decided to try it herself. She opened her stand the same way as Lucinda, but she has lots of money saved up so she has no plans to raise additional capital. Since she’s flush with cash and she knows there’s not much difference between lemonades, Meg has a plan: she decides to offer her lemonade for a nickel less than Lucinda. Many neighbors start going to Meg’s stand where the lemonade tastes just as good but costs less. Some customers stay with Lucinda out of loyalty, but even they admit there’s not much difference in the product.

In time, the opening of Meg’s stand really cuts into Lucinda’s business. Where Lucinda used to sell 50 cups of lemonade a day, now she’s selling only 25. In other words, her sales have declined by 50%. The decline in sales has had the disastrous effect of squeezing her net income, the profit left over after she pays all her business expenses and taxes. Lucinda has taken on some additional costs since she started her business: she has one employee, and she also needs to pay the interest on George’s bond.

Meanwhile, Ella has gotten wind of the problems at Lucinda’s. She knows that Meg is offering lemonade at a cheaper price and feels this may spell trouble for Lucinda. So she decides to try to sell her share. But when she tries to sell it, she finds no takers. Most people have heard of Lucinda’s problems, and no one wants to buy a share in a struggling business. Ella quickly realizes that the investment she thought was risk-free somehow involves risk after all.

Along comes a neighbor named Donna, a seasoned bargain hunter, and she offers to buy the share for $6. Ella is shocked at the low offer, but feels $6 is better than nothing. She wants to get something back on her initial investment, given that the share has turned out to be illiquid — meaning that not many people want to make an offer on the share at all. Ella exchanges her stock certificate for the $6 and walks away relieved. Donna takes the certificate, happy with what she feels is a great bargain. How can Donna and Ella both be right? The answer is they can’t. The share is either worth more than $6 or less than $6, in which case one of them is wrong. Or the share is worth exactly $6, in which case they are both wrong. Although they might not both be right, they may have each made a good decision for their respective needs. Donna may be best able to bear the risk of the share since she has more dollars and isn’t particularly worried about losing six of them — while Ella needs to pay her cell phone bill and those six will come in handy.

As you can see, often one person is in a better position to bear certain risks than another and so they swap risks. In many ways, this is what creates markets, such as the stock market.

You can also see that Ella had a certain risk attached to her investment. This first risk is known as business risk, and it affects every business owner. This risk occurred in a big way: Ella only recovered half her initial pot, making the return on her initial investment a negative 50%. Not so stellar after all. Though Ella fell prey to business risk, her actual demise came in the form of price risk, or the risk that the value of her share would decline. In other words, the business risk led to price risk, and Ella ended up poorer than she started.

What about George’s risk when he bought a bond in Lucinda Lemonade Inc? His bond gives him an annual interest payment on the amount of his loan. One big difference between George’s bond and Ella’s stock is that Lucinda Lemonade has pledged to return George’s principal in five years but has made no similar promise to Ella. As a shareholder, Ella does not have any contractual promise of getting her money back. George, on the other hand, will get back his principal after five years once the bond matures. And he will get his interest payments until then. Is there any risk to George’s investment? At first glance, it doesn’t seem so. But remember what we said about risk. If someone claims it doesn’t exist, turn and run the other way.

George’s bond investment is subject to risk – not the same risk as Ella’s stock, but some risk just the same. Let’s see what happens to George’s bond when Lucinda Lemonade Inc. runs into hard times.

Meg’s stand is humming along. Even Lucinda’s first loyal customers are lured by the promise of cheaper drink. Lucinda’s sales have plummeted. She’s now taking in less money than she’s shelling out for lemons, sugar, and wages. You guessed it: her business is now losing money. It’s unprofitable. What’s more, Lucinda is having trouble making her interest to George. She misses one payment, prompting a worried call from George himself. Lucinda tells George she can no longer make the payments, at least until the lemonade business improves. Lucinda says she just can’t come up with the cash. This means that her bond is now in default. She wants to make the best of a bad situation and doesn’t wish to declare bankruptcy (a process by which she can have most of her debts forgiven but probably lose the business), so she offers to sell the juicers and give George the proceeds, a deal to which George agrees. Meg, opportunist that she is, hears of Lucinda’s troubles and offers to buy the juicers for $40, less than Lucinda paid for them. After all, Meg’s stand is booming and she could really use the juicers. She figures that by using the juicers, she can improve her productivity and afford to cut her prices even more.

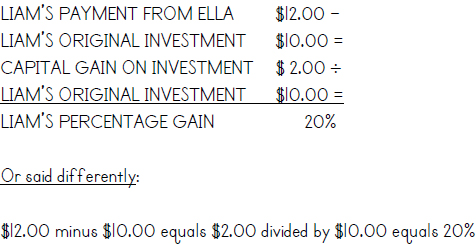

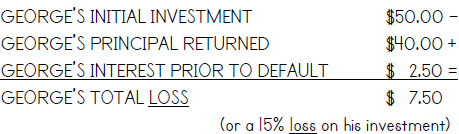

Lucinda gives George the $40 from the sale of juicers as a partial payment of his principal. Given the sorry state of things, there’s not likely to be more coming. George considers himself lucky and writes off the remaining loss:

As you can see through the jaundiced eyes of George, even a bond investment can turn out to be a lemon. Entire countries have been known to default on their bonds when they can’t pay the interest. In 1998, Russia defaulted on its bonds, sparking a worldwide debt crisis. In 2002, Argentina did the same thing. More recently, many European countries have had trouble paying the interest on their bonds. So bonds have risk, but generally less risk than stocks since they have a promise of repayment, however meaningless such a promise can become.

Generally, bonds issued by a company, or corporate bonds (like the bonds bought from Lucinda Lemonade Inc.), are riskier than government bonds. But as you can see from the history of countries with debt problems, this is not always true. A bond in a solid company is often safer than a government bond in a risky country. Bond risk can be determined by the credit rating, the grade a bond gets on how likely it is to be paid back. Lucinda Lemonade Inc.’s bonds would get a relatively low, or “junk” rating. Junk bonds are bonds that have a high risk of default. On the other hand, U.S. government bonds, once the closest thing to risk-free, used to receive the highest rating of all. Different independent rating agencies like Standard & Poor’s, Fitch, and Moody’s rate bonds. If you buy a bond, check its rating first. The bond rating companies are not always reliable, however. The best thing to do is to check out the financials of the bond issuer yourself.

Different risks for different folks, as they say. Just be sure you’ve considered the risks before you buy anything: a stock, a bond, or even a cup of lemonade from the corner stand.

“Put all your eggs in the one basket and — watch that basket!”

- Mark Twain

It gets a little risky putting all your eggs (or lemons) in one basket. In spite of Mark Twain’s quip, it can lead to disaster — even if you do “watch that basket.”

Many things are beyond our control. Watching your basket is a decent way to manage risk. But even with the closest watch, one basket can meet a bad end. Far better to distribute eggs in different baskets. This concept of putting eggs in different baskets, or spreading the risk, is known as diversification.

Let’s say a savvy neighbor named Abby decides it’s a good idea to invest in Meg’s Lemonade Stand. She offers Meg $40 for a tenth of the business. Meg, despite her qualms, decides that $40 for a tenth of the company is a nice chunk of change. She wants some extra cash to invest in expansion, so she sells the share to Abby for $40.

But Abby doesn’t stop there. She remembers it wasn’t long ago that Lucinda was the lemonade queen before things soured. Abby knows that the best company can run into trouble: that a new competitor can emerge overnight, a new juicing method can rear its ugly head, or one bad lemon can ruin the mix. It occurs to Abby that if she owned shares in both of the town’s lemonade businesses, she would be hedging her bets; that is, she would make some money no matter which business eventually triumphed. So she approaches Donna (our shrewd investor who bought a share of Lucinda Lemonade Inc. from Ella for $6 when things looked really bad) and buys the share for $7. Abby has diversified her investments — she has spread her risk between two different lemonade companies.

Abby looks especially smart in retrospect because the day after she buys her shares, Lucinda Lemonade Inc. announces a new product: iced tea. Lucinda had a hunch that iced tea might be a popular item and a way to win back some of the business from Meg. Lucinda has done a little cost analysis, and she calculates that it’s two pennies less expensive to make a glass of iced tea than a glass of lemonade. She figures she can sell the iced tea for the same price as the lemonade. So she’ll make two pennies more on each glass of iced tea than on each glass of lemonade. In other words, the iced tea will be a higher margin product and will increase her overall profit margins. The strategy works: many customers who had once strayed from Lucinda return to her stand. They love the iced tea. In addition, Lucinda develops some new customers who dislike lemonade but are always up for a tall glass of iced tea. Now the balance of power shifts: Lucinda starts gaining back business, or market share, from Meg. And Abby is happy: diversifying her stock portfolio was a good idea. Does she decide to sell her share in Meg’s Lemonade now that it may have lost value? No, because she wants to keep things diversified in case the balance of power shifts again. This type of risk — the risk that one company will be crushed by its competitor or by some unfortunate event — is called company-specific risk.

By adding iced tea to her menu, Lucinda has also diversified, just in a different way. Rather than diversifying her investment holdings, she has diversified her product line by adding a second item to her menu. As you can see, diversification can benefit not just the investor but also the company itself.

You may have noticed that Abby’s shrewd stab at diversification is not foolproof: By owning two businesses instead of one, Abby will always own the underperforming business as well as the outperforming one. If you think about it, this is a logical certainty. So Abby is essentially hedging, or protecting, against the risk that one lemonade stand will outdo the other by owning both. By hedging her bet, Abby is paying the price that one lemonade stand will also always lag the other, pulling down her overall investment return. Like insurance, hedging can provide protection, but only at a price.

This leads to Lemonade Law #4:

If Abby were to choose only the “best” company and stick with it, she would rake in the biggest gains. But choosing the best company is a crapshoot. So Abby manages her risk by diversifying, or spreading the risk between two different competitors. This way, Abby can sit back and watch the lemonade stands squeeze each other, knowing she’ll win something either way. Diversification limits risk and therefore also limits potential return, whereas not diversifying increases risk and increases potential return.

Abby’s diversification doesn’t manage all risks. It doesn’t protect against the whole lemonade craze going belly-up. What would happen if people stopped drinking lemonade? Let’s say (just for fun) that the U.S. Surgeon General announced that lemonade causes pimples. People might stop drinking lemonade. This would not only squeeze Lucinda but also Meg. Both sell lemonade, and both would suffer the consequences. You’re probably scratching your head and saying, “But Lucinda also sells iced tea, so she’s going to do OK.” And you’re right: Lucinda will do better in this scenario than Meg because she diversified her product line and has more up her short sleeves than just lemonade. But what if the U.S. Surgeon General declares that not only does lemonade cause pimples, all cold drinks cause them? Then both Meg and Lucinda would be in trouble.

This type of risk, where a whole type of business might be dealt a blow, is called sector risk. Here, the whole cold drink sector is being squeezed. The only way for Abby to diversify against sector risk is for her to own businesses in different sectors: Abby could buy shares in a hot coffee stand in addition to her two lemonade stands. Now she’ll still be OK if the cold drink sector turns lukewarm. She’ll also be fine during the winter when the cold drink sector might have tough times on a seasonal basis.

Hedging is a tricky thing in general. Most hedges, or protections against loss, are imperfect. They may or may not do exactly what they’re supposed to do. Buying a second lemonade company may help manage the risk of owning the first one — or it may not. The worst thing about hedges is that they often fail just when they’re needed most. Never rely solely on a hedge to manage risk. The best way to manage risk is to know and understand what you own. There’s no substitute for that. As they say, the only perfect hedge against an investment is to sell it.

You get the idea behind diversification and other types of hedging. Though they protect against some risks, they can’t manage all risks. No investor, for example, has yet figured out how to diversify against the risk of the Earth falling out of the Sun’s orbit.

“What is a cynic? A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

- Oscar Wilde

Have you wondered how prices are put on shares in the first place? How did Liam and Lucinda ever decide on $10 as the price for one share of Lucinda Lemonade Inc? This is not only a good question; it’s the crucial question.

In spite of Oscar Wilde’s definition, I think someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing is just a bad investor. Every publicly traded stock has a price, but whether that price matches its actual value is another thing entirely. Before we get to stocks, think of a home listed for sale. If the seller has to sell to move for a new job, she will be motivated to lower the price quickly. This might lead to an asking price less than the fair value of the home. A buyer would snap it up fast. A bidding war might emerge, but in a slow market, the home just might sell for an artificially low price.

The same thing happens with stocks. People who need to sell quickly – for whatever reason, whether to pay off a loan, settle an estate, or react to panic – will often accept a price per share far less than the real, underlying value of that share. At times of extreme fear, such as the stock market bottom of March 2009, people will literally give stocks away, so scared are they that prices will just keep falling. The only thing that protects you from being a seller at times of panic is an understanding of the true, underlying value.

On the flip side, there are times when people get too giddy and optimistic about stocks, as during the Internet bubble of 1999. This causes them to buy stocks at dizzying prices, at levels far in excess of the real value. Stock markets are especially prone to these manic-depressive swings because it’s so easy to buy or sell a stock with one click. A house is harder to sell, and so real estate prices move more slowly. People also can understand the value of a home, even when the price declines, because you can touch and feel it. And you can live in it. Understanding the value of a stock is a more abstract concept but one that can be learned.

There are people who would like you to think that putting a value on a company is rocket science. Many brokers, money managers, analysts, and investment bankers get paid a lot of money to do this, and they would love people to think it’s some mystical numerology, unknown to any but the anointed few. Lazy people make investments without calculating values at all, feeling it’s not worth the work. The truth lies somewhere in between. Valuing companies is not impossible. And the truth about valuation is that anyone can do it if willing to put in the time and effort. On the other hand, ignoring valuation is a sure way to lose your lemons.

So how do you put value on a share — that is, on a part of a company?

We won’t bother you with the actual methods of valuation now. That will come near the end of the book, once you have other concepts under your belt. For now, just remember that a stock has both a price and a value, and the two are often very different things.