“Death and taxes and childbirth! There’s never any convenient time for any of them.”

- Margaret Mitchell

The lemonade stand investor does not escape the tax man. For investors, taxes are a way of life, however inconvenient. And they’re as American as a summer Sunday but not quite as welcome. Taxes are the grim side of any happy investment. Assuming you hit the jackpot on a stock, the government will squeeze you for its share. The trick is to leave some juice for yourself. This requires knowledge and planning.

This leads to Lemonade Law #6:

The wise lemonade stand investor spends some time learning the ins and outs of taxes. Unfortunately, the tax code is outlandish in its complexity. But it’s yours. And if you want to hold onto your gains, you better know the basics. Before you curse the IRS, remember that our bloated tax code is not their fault. They merely enforce the tortured rules and regulations that our legislators enact with frightening regularity.

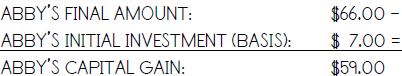

Let’s revisit Abby, who struck it rich on her investment in Lucinda Lemonade Inc. Now that a share of Lucinda Lemonade is trading at $66, Abby thinks it’s time to take some profits. After all, she purchased her stake for the slim price of $7. Not too shabby. Continuing her streak of shrewdness, Abby does a thorough analysis of the potential tax consequences. She knows that when you sell an investment at a gain, you pay what’s called a capital gains tax, or simply a tax assessed on the gain in capital she made over her initial investment. This initial investment is known as her basis. Since Abby has made a gain of $59 above and beyond her basis, she will owe a tax on that amount:

Abby’s next step is to determine the tax rate at which the capital gain will be taxed. This is a tad more complicated. Abby does a little research and learns that there are basically two types of capital gains: short-term gains and long-term gains. Short-term gains are gains on investments held (or owned) for a year or less, while long-term gains are gains on investments held for more than a year. Abby calculates that her gain on Lucinda Lemonade Inc. would be short-term since she’s owned her stake for only eleven months.

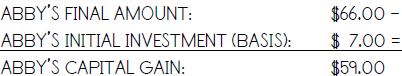

After consulting with her accountant, Abby learns that a short-term gain is taxed at her ordinary income tax rate: the same rate at which her normal salary is taxed. Abby’s ordinary income tax rate is about 30%, so her short-term capital gains tax rate will be the same:

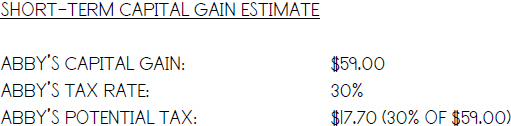

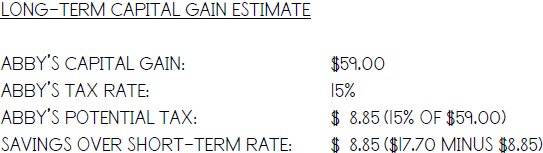

But there are options for Abby to reduce this tax bill. The accountant, being an accountant, points out that if Abby were to merely hold her investment for longer than a year, she would owe a smaller tax. In fact, Abby’s rate on a long-term gain would be only 15%, the maximum percentage at which long-term capital gains can currently be taxed (note: this rate is scheduled to rise in 2013 unless altered by new legislation). So if Abby were to hold the stock for only another month or so, her tax would be only $8.85:

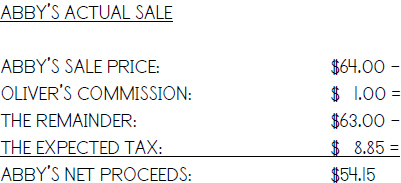

Abby decides to wait for another month and a day, mindful that she must hold the stock for longer than a year in order to qualify for the lower tax rate. Once the time has passed, the stock is trading a little lower (at $64 per share), and Abby places a sell order with Oliver. Oliver sells the stock, deducts his commission of $1 (she gets to add this $1 to her basis to lower the tax) and passes along the remaining $63. Abby reserves $8.85 for the tax she will have to pay:

Abby happily carts the net proceeds of $54.15 over to the bank. She deposits the money in a savings account until she decides where to reinvest the money.

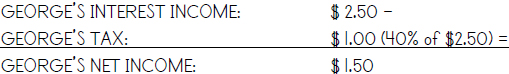

The tax man is not content with only capital gains. He puts the squeeze on other types of profit as well. Take George, our early bond investor in Lucinda Lemonade Inc. When George purchased the bond — that is, when George lent money to the company in exchange for receiving interest — George received income. This income is taxed a little differently than capital gains but is taxed nevertheless. You may recall that George was receiving 5% interest on the $50 he had lent to Lucinda Lemonade Inc. until the company defaulted on its bond. In the time he was receiving his payments, he received a total of only $2.50, a figure George doesn’t like to be reminded of. Adding insult to injury, this interest income is considered ordinary income, taxed to George at his ordinary income rate. Since George holds a job as a lemon consultant, a highly paid gig in lemonade stand communities, his ordinary income total tax rate is 40%. This means that George will owe taxes of 80 cents on his $2.50 income, leaving him with a lot less:

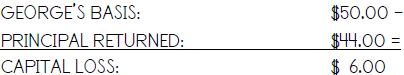

But fortunately, George gets a small gift: a deduction, in this case for the principal lost on his unsuccessful bond. We are taxed on gains, but we also get a break on losses. George lent $50 in the form of a bond to Lucinda Lemonade Inc. When George invested the initial $50 in the bond and only got back $44 due to the default, he suffered a $6 capital loss:

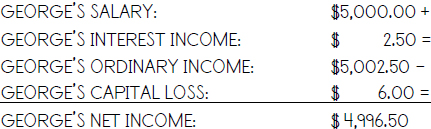

This capital loss may be deducted against any capital gains George had. But since George had no gains, he can still deduct the $6 loss against his ordinary income. In fact, taxpayers can deduct up to $3,000 in capital losses against their ordinary income in any given year. Beleaguered George enjoys a little luck after all. He is able to deduct the full $6 of his loss against his ordinary income as follows:

George will only pay ordinary income tax on his net income of $4,996.50. Therefore, his $6 loss came in handy as a tax deduction, reducing his taxable income by that same amount.

As you can see, taxes get complicated and we have only scratched the rind. This basic knowledge of investment taxes can steer you in the right direction. Just understanding the difference between ordinary income and capital gains can be helpful. But tax issues have a way of becoming more miserable than they seem, and it’s best to hire a qualified accountant. An accountant can be the best money you’ve ever spent. If you’re not convinced by reading this chapter, then just sit down alone next April with a pencil and your brokerage statements. And don’t email me: I’ll be busy preparing my tax file for my accountant.

“When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.”

- Elbert Hubbard & Others

Taxes call for making the best of a bad situation. In the world of investment, you can do a few smart things to reduce your taxes. An accountant can help plan a tax strategy for your investments, but there are some basic tools every investor should know. Did you know, for example, that a bond yielding 3.5% can pay you more than a bond yielding 5% in the bizarre world of taxation?

The first tool for avoiding taxes is to invest in tax-free investments. You may be shocked to hear that something so certain as taxes can have its comeuppance. But indeed it does in the form of municipal bonds, tax-free bonds issued by states, counties, and cities (municipalities). Remember that when George bought a bond, he was really just lending money. If George buys a municipal bond, he is also just lending money — this time to a municipality. Municipal bonds are tax-free to the residents of the state of issue.

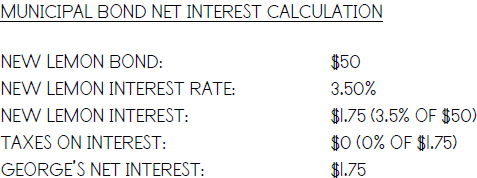

After George’s Lucinda Lemonade fiasco, he forswears corporate bonds, deeming them too risky. He realizes he can purchase municipal bonds issued by his very own state, New Lemon. The interest payments of New Lemon municipal bonds are free from both state and federal income tax to New Lemon residents. He also knows that lending money to the government is less risky than lending to a corporation since a government is generally less likely to go bankrupt and avoid its obligations. Unlike a corporation, a municipality can tax its residents to pay the bills. But George gets discouraged when he learns that New Lemon bonds are only paying 3.5% interest. How can he possibly get ahead on such a miserly rate? Along comes Abby to explain that municipal bonds are tax-free, and their real interest rate is higher than it appears (especially for those in high income tax brackets). She explains that since George is taxed at a 40% rate, a 3.5% tax-free interest rate is actually very good. Abby shows that if George purchases a $50 New Lemon bond paying 3.5%, he will get $1.75 in net interest per year:

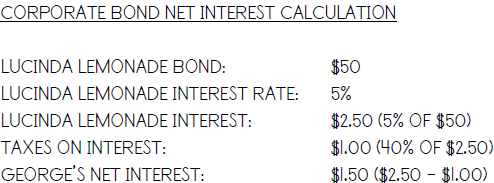

Because New Lemon interest is tax-free to state residents, George will not have to pay any taxes at all — he can keep the full $1.75 for himself. But with a corporate bond (such as the one issued by Lucinda Lemonade Inc.), he was required to pay tax on the interest payment. If George had received a full year of interest on Lucinda Lemonade’s bond paying 5%, he would have received $2.50, of which $1.00 would have disappeared in the form of taxes, leaving only $1.50:

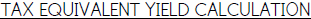

George is surprised to learn that a tax-free bond paying 3.5% can actually let him keep more money than a taxable bond paying 5%. Abby explains that there’s a formula (known as the tax equivalent yield calculation) to determine whether a tax-free rate is better than a taxable rate for any given investor — a result that will always hinge on the investor’s income tax rate.

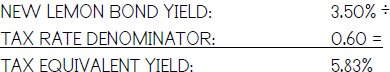

Abby demonstrates this simple formula as follows:

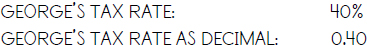

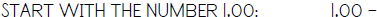

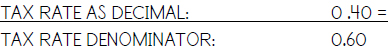

You first list your tax rate expressed as a decimal:

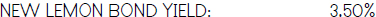

Then you take the yield of the bond, that is, the rate that the bond pays out in interest:

You then subtract your tax rate (expressed as a decimal) from 1.0 to get your tax rate denominator:

Finally, you divide the bond yield by the tax rate denominator to get your tax-equivalent yield:

The tax-equivalent yield is the yield that the tax-free bond is effectively paying you in taxable terms. In other words, the tax-equivalent yield is the amount you would have to earn on a taxable bond to match the yield on your tax-free bond. Therefore, George would have to earn 5.83% on a corporate bond (or any other taxable bond) in order to get the same return he can get with his New Lemon tax-free municipal bond.

George wants to run out and buy municipal bonds, but Abby warns him that he still has some homework to do before he buys anything: He should investigate the credit risk of the bond — that is, the risk that the municipality might not repay. Municipal bonds tend to be fairly safe, but some are not. He can check the ratings of the major agencies like Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s. As mentioned ealier, ratings are not foolproof. Abby recommends checking the underlying finances of the municipality that issues the bonds. Abby explains that he should also review the terms of any bond he purchases, including the length of time until the bond matures. If he sells his bond before the date of maturity, he may lose some of his principal. In addition, he should make sure he understands any other additional terms of the bond, such as whether the bond can be called (or paid back) prematurely, whether the bond is insured, and whether the bond is fully tax-free.

As you can see, municipal bonds can also get complicated, and are another area where a professional can often be of assistance. But it’s good for any investor to know the basics of municipal bonds.

“When life gives you more lemons, make more lemonade.”

- Anonymous Lemonade Stand Investor

The other best way for most investors to avoid taxes is to invest in accounts that are tax-deferred or tax-free. These might sound like more unexpected gifts from the government. They are. The surprising thing is how many people look these gift horses in the mouth. There are many such accounts, usually referred to as retirement accounts, since the money in them is intended for use in retirement. A detailed survey of the rules governing these accounts is beyond the scope of this book, but we’ll run through the basics.

Along comes Abby, our most successful lemonade stand investor. Abby has made money in the stock market, but she’s also made some in her job as a lemon inspector: she sniffs all lemons headed for the lemonade stands to ensure overall quality and taste. As a lemonade inspector, Abby makes $8,000 a year in earned income, the money she earns by working. Abby decides to take $5,000 of the total and put it in a type of tax-deferred account: an IRA, or individual retirement account.

An IRA is a tax-deferred account that allows ordinary people with earned income to save for retirement. The mechanics of an IRA are fairly simple. Abby opens the IRA at a bank or brokerage firm. She deposits $5,000. The beauty of the IRA investment is two-fold: (1) Abby gets an immediate tax deduction for the $5,000, and (2) the $5,000 is allowed to grow tax-deferred until she’s forced to take it out by the government at the age of 70 ½, at which time she pays ordinary income taxes on the withdrawals. In the meantime, Abby can invest the money in pretty much any sensible way (there are certain prohibited types of investments) and watch those investments grow without paying taxes on them for a long time (the tax is deferred).

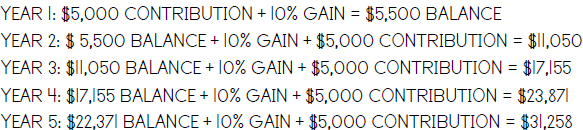

Let’s see how it works. Assuming Abby invests $5,000 a year in an IRA for five years and gets a 10% annualized return on that investment; she will end up with $31,258:

If Abby maintains this pace for another 35 years, she’ll retire with $2,233,548 — no shabby sum. The money compounds over time. In other words, each year’s 10% gain is made on the accumulated balance. More money is then contributed, leading to rapid growth. And since the gains are tax-deferred, no money has to be paid to Uncle Sam until retirement. This is the miracle of tax-deferred compounding, by which an investment grows in leaps and bounds. In fact, just one single dollar invested in stocks in a retirement account a century ago would be worth over $10,000 today! Though the annualized return was just 9.66% per year, the miracle of compounding leads to that phenomenal result. A quick way to estimate compounding in your head is to use the Rule of 72. If you divide 72 by the annualized rate of return, you get the number of years it takes money to double. For example, at 10% per year, money doubles every 7.2 years (72 ÷10 = 7.2).

Another type of IRA — a Roth IRA — allows for tax-free, not just tax-deferred, gains. With a Roth IRA, Abby would lose the up-front deduction on her contribution, but she would never, ever have to pay taxes on the investment gains. A Roth IRA is a permanent tax dodge that’s perfectly legal. Roth IRA’s are only available to people under certain income levels.

A third type of IRA that is available to people with self-employment earnings (earnings derived from their own business) is the SEP-IRA, or simplified employee pension. A SEP allows for far larger contributions than the IRA maximum and is very useful for small business owners looking to create a simple pension plan.

Finally, many people who work for large businesses or institutions are eligible for 401(k) or 403(b) plans, retirement plans for employed individuals that are also tax-deferred. It’s almost always a good idea to enroll in these plans because they allow you to squirrel away more money than an IRA. In addition, some employers will match every dollar you contribute with a dollar of their own, leading to supercharged savings.

There are hooks to retirement plans. For starters, the money gets locked up until age 59½. It’s difficult to withdraw money from a retirement plan before that age without paying a penalty. In addition, there are complex rules regarding eligibility, contributions and withdrawals. And these rules change frequently, making it imperative to consult an accountant or investment advisor if you’re interested in any type of retirement account.

The bottom line: not participating in some type of retirement plan is akin to throwing good lemons out the window.