“Nothing so weakens government as persistent inflation.”

- John Kenneth Galbraith

Inflation is the bitter rind in the investment mix. Inflation can spoil the otherwise perfect labor of any investor and render an investment plan pointless. No doubt we all understand the basic concept: Inflation makes things go up in price.

If there’s high inflation in the state of New Lemonade, a cup of lemonade will become less affordable every day. In other words, it will rise in price. While a cup of lemonade was selling for 20 cents last year, this year, it’s selling for 21 cents. The increase in price is one penny, an increase in percentage terms of 5%:

We can say that the inflation rate is 5%. The inflation rate is the rate at which prices increase over time. Historically, the average annual inflation rate runs around 3%, but there have been periods where inflation has been much higher.

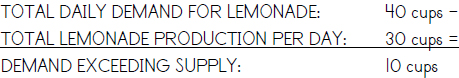

What causes this bizarre result? It doesn’t necessarily seem a foregone conclusion that prices should always go up, but they seem to. Economists endlessly debate the reasons. Most economists believe that inflation is caused by “too much money chasing too few goods.” In other words, if people have a lot of money to spend but not many things to spend it on, prices will rise. For example, if more and more people have more and more money in Lemonville, there will be a lot of money flowing around to buy lemonade. In fact, people may be throwing money at lemonade faster than Lucinda Lemonade Inc. and other stands can squeeze the stuff. If this occurs, the price of lemonade will rise. It’s a simple case of supply and demand. If the demand for lemonade increases while the supply does not, an imbalance will result and prices will rise. Let’s look at a specific example to make sure we really understand the concept. Suppose people in Lemonville demand 40 cups of lemonade each day, while all the lemonade stands put together in Lemonville are only able to squeeze out 30. Demand thus exceeds supply by 10 cups:

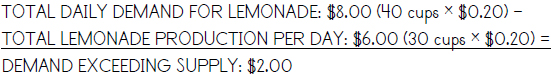

Since we know that a cup of lemonade costs 20 cents, we can also express this imbalance in terms of dollars:

There are two more dollars of demand for lemonade than there is supply. In other words, there’s an extra $2 sloshing around the pockets of Lemonville residents than there is lemonade to buy.

There are two ways for this imbalance to be corrected. Either the town’s lemonade stands will (1) raise their prices to soak up the excess money, or (2) they will improve their productivity to squeeze more cups.

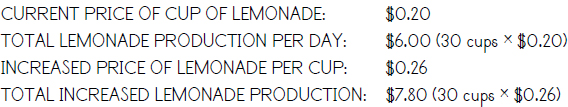

Let’s look at option #1: Lemonade stand owners being businesspeople, they will choose to raise their prices if they can. Whether they can or not is determined by whether they have what’s called pricing power — the ability to raise their prices without losing customers. If lemonade stands have pricing power, they can raise their prices to $0.26 per cup and take advantage of the excess demand:

By raising their prices to $0.26 a cup, the lemonade stands have brought the production of lemonade back in line with demand. They can’t really push their prices much higher because there’s only $8.00 per day in available daily dollar demand and they have already pushed production up to $7.80 per day. They are now soaking up the total money supply. In other words, they are charging nearly the highest prices that the market will bear.

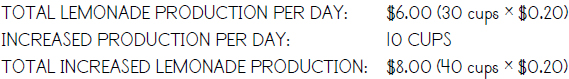

Now let’s look at option #2: If the lemonade stands can buy new technology that will allow them to produce more lemonade, some smart, enterprising owner will eventually choose that option in order to undercut the competition. Let’s assume that Meg learns about new electric lemon squeezers that allow lemonade to be made much faster than the old-fashioned manual kind (which in turn makes lemonade faster than squeezing lemons by hand). Meg buys an electric squeezer and finds that she can now produce twice as many cups of lemonade each day than she used to. Where she used to be able to squeeze only 10 cups per day, now she can squeeze 20, adding 10 more cups to the total daily output in Lemonville. The town’s total output of lemonade is now 40, bringing the supply-demand situation back into balance:

By raising the total amount of lemonade produced each day to 40 cups, Meg has raised the total dollar output of lemonade production each day to $8.00, perfectly matching demand. Balance has been restored.

More impressively, Meg has stolen Lucinda’s pricing power. Now Lucinda can’t raise her prices because her customers will just go to Meg where they can buy more cups at the cheap price of 20 cents. Increasing productivity, that is increasing the daily output of lemonade, has led to an environment without pricing power. It has also led to an environment of economic growth because the dollar value of goods produced is increasing. This is the best economic environment to have: one where economic growth exists hand in hand with increased productivity so that excess demand does not lead to inflation.

As you can appreciate, this is a difficult balance to pull off. If there isn’t the means required to increase productivity (i.e., new electric juicers), then prices will rise without increased output of lemonade. The result will be good old 1970s-style stagflation: inflation on top of a period of declining growth — a recession.

This is why innovation is so crucial to a growing economy. A high growth/high productivity/low inflation environment is what creates jobs, wealth, and prosperity. The opposite leads to economic decline. Enough said.

“I don’t believe in princerple, but oh I du in interest.”

- James Russell Lowell

In the last chapter, we talked about how “too much money chasing too few goods” causes inflation. And we also showed how “too few goods” (too few cups of lemonade) can result from a lack of productivity. Well, what about the money side? In other words, how does “too much money” happen?

“Too much money” may not sound like a problem. If such a problem exists, you might like to be the one to have it. Too much money is only a problem if accompanied by “too few goods.” If increased productivity leads to enough lemonade for all that money to absorb, it’s fine. But if there’s more money than lemonade, the imbalance called inflation results.

Well, how does “too much money” occur? One way is by the government printing too much of it. It may have often occurred to you that if the government needs money, why don’t they just make more. The answer is that printing more dollars just pumps more money into the system. And too much money without a corresponding increase in production causes inflation. If the government were to just print money any time they felt the urge, it would lead to very bad inflation.

Money printed without corresponding growth is not a true increase in wealth because the money loses its value due to inflation. For example, let’s assume the citizens of Lemonville suddenly have much more money because the government is giving away dollar bills on street corners. The government passes a new law that says that money should be given out from corner stands, and that people can take as much as they want. If the stand runs out, the government prints more. Naturally, every Lemonville resident visits the stand and carts away as much money as possible. After awhile, every resident has a big fat wallet. Now when they go buy lemonade, they really don’t care what price they pay. After all, money is free and anyone can afford as much as they want. Sounds like lemonade ambrosia.

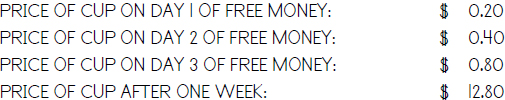

But watch what happens:

Meg and Lucinda both find that they can charge as much as they want because the market will bear an infinite price. They double their prices daily, finding that no matter how high they go, they can still go higher. Money is so free that it has lost its meaning. Prices of lemonade go through the roof:

You get the idea. Soon a cup of lemonade will cost over a thousand dollars. This is what’s called hyperinflation, inflation so extreme that money loses its value. People start hoarding lemonade because the price only goes up, up, up. Soon, the supply starts to run out, leading to even higher prices. Even Lemonville millionaires cannot afford a cup of lemonade. As fast as they can cart dollars away from the money stands, the price goes up past the point at which they can afford it. After some time, the money, or currency, has been debased, meaning it has been rendered valueless. At the point where no sum of money can buy you lemonade, money has lost its purpose. The economy has effectively ceased operating, and the results can be disastrous.

Some of the more harmful results of this scenario are at first difficult to predict. Meg and Lucinda, for example, would soon leave the lemonade business. After all, why should they work so hard squeezing lemons if money is free on street corners? And as fast as they raise their prices for lemonade, a chain reaction causes the supermarkets to raise the price of lemons, making business impossible. The cycle becomes an especially vicious one. At a certain point, the incentives to work, save, invest, and do all things productive disappear. Chaos and social disorder result.

This is why nations without good monetary policy (control of the money supply) often have failing economies. And failing economies lead to poverty. The bottom line is that it’s crucial that a government control the monetary supply. In other words, a country cannot simply print more money to solve its problems. A country that prevents an oversupply of money is a country with monetary discipline.

How then does a government control the amount of money flowing down Main Street? By regulating the cost of money, otherwise known as interest rates. It being impractical for any government to really turn on and off the printing presses, they use a better trick: controlling the cost of money by controlling interest rates. In the United States, this duty falls to the Federal Reserve (the Fed), the government entity responsible for monetary policy. The Fed meets regularly to decide on interest rates. When they feel there is too much money flowing through the system, they make money more expensive—that is, they raise interest rates. When they fell there is too little money, they make money cheaper—they lower interest rates. The Fed doesn’t actually change all interest rates. Instead, they change a key rate known as the federal funds target rate, which affects the rate at which big banks borrow money from each other. By changing the federal funds target rate, they effectively change most rates, given that the federal funds target rate is the rate upon which all other short-term rates are based.

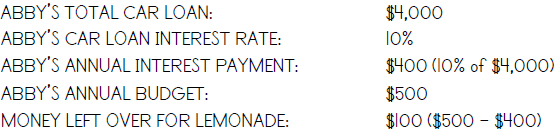

Let’s see how this works in Lemonville. Assume that Abby, having pocketed some money from her successful investments, looks to buy a car. She decides to spend $5,000 on a “Lemon,” which in Lemonville is a great car, not a lemon. She plans to put down $1,000 and borrows the remaining $4,000 from the bank. The day before she goes to buy the car, the bank is charging an interest rate of 10% on car loans. This means that Abby would pay an annual interest payment of $400. That would leave her with an extra $100 from her annual budget to indulge her love of lemonade:

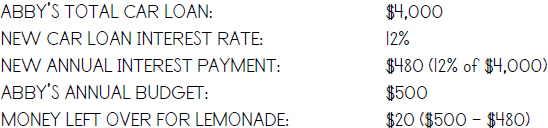

Unfortunately for Abby, the Fed meets that very day and decides there’s too much money flowing through Lemonville and everywhere else. They’re concerned that this oversupply of money could lead to inflation. They respond by raising the federal funds target rate from 5% to 6%. As a result, Abby’s bank now has to borrow its own money at 6% instead of the old 5%. They in turn do exactly what you would guess: pass along the higher borrowing rate to their customers. Thus, Abby’s bank raises the interest rate on car loans from 10% to 12%. Now Abby finds that if she purchases the car, she will have to borrow money at 12%, meaning that her annual interest payment will be $480, leaving her with only $20 left over for lemonade:

With only $20 extra, Abby will certainly be buying less lemonade. The Fed has effectively reduced Abby’s demand for lemonade by cutting down on the extra cash she has in her wallet. The Fed has tightened the money supply by raising interest rates and increasing the cost of money. By increasing the cost of money, the Fed has reduced the supply of money. In doing so, they have brought supply and demand back into balance, reducing the risk of inflation.

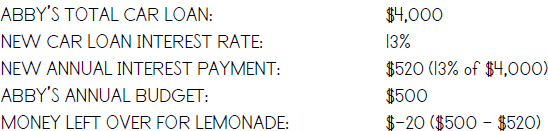

If the Fed miscalculates and tightens the money supply too much, they could stifle all demand for lemonade, leading to a collapse in supply and a lemonade recession. For example, if they were to raise the fed funds rate all the way to 7%, it would push the bank car loan rate up high enough (say to 13%) to really damage Abby’s buying power:

With interest rates so high, Abby has no money left over to spend on lemonade. In fact, she is now losing $20 each year, meaning she will have to cut back on some other expenses beyond lemonade. If you can imagine this tightening of money occurring — not just with Abby — but with every Lemonville resident, you can see how the demand for lemonade and other things could be choked off, sending the lemonade stand business into recession and crushing the Lemonville economy. If so, the Fed would have to reverse direction, drastically cutting interest rates in order to allow more money to flow through the system, thereby stimulating demand. When the Fed cuts interest rates to stimulate demand, they are loosening up the money supply, adapting what is called a loose monetary policy.

If the Fed failed to stimulate demand, supply could exceed demand, leading to the opposite type of imbalance from inflation: something known as deflation, where prices fall over time. Deflation can be worse than inflation because it implies there is very little demand in the economy. With rampant deflation, the economy runs the risk of slipping into a deflationary spiral, a vicious circle where lower prices lead to lower profits which leads to lower employment which then leads to lower demand and even lower prices, and so on. A deflationary spiral often results in a depression, a state in which the economy shrinks for a long period of time, leading to layoffs and misery. The last depression in this country occurred in the 1930s.

As you can see, the Fed has to get the direction of the economy right, and they only have one major tool to get the job done: interest rates. In the wake of the financial collapse of 2008, the Fed got it right, loosening the money supply drastically and preventing another Great Depression.

Think of the Fed’s interest rate decisions as opening and closing a faucet: When the Fed wants to let more money flow through the economy, they open the faucet by lowering rates; when they want to cut off the flow of money through the economy, they close the faucet by hiking rates.

It sometimes seems like the Fed has the toughest job in the world, even though they only have one major decision: open or close the faucet. As you can imagine, a lot goes into that one decision.

“The thing that most affects the stock market is everything.”

- James Palysted Wood

How, then, does all this perplexing interest rate stuff relate to the big picture?

Interest rates and inflation both have tremendous effects on the value of stocks and bonds — and any other investment, for that matter. The way in which the levels of interest rates and inflation impact investments is sometimes referred to as macroeconomics.

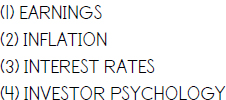

Broadly, there are four factors that decide the fate of stocks:

Of course, there are many other things that come into play, such as politics, psychology (and your lucky pair of red socks), but these other factors are really only important in how they affect the big four. These four factors are so important because they are the levers pulling supply and demand, which in turn create the dynamic that determines stock prices.

The first of these factors, earnings, is dependent on an individual company’s success or failure. In other words, a lemonade stand’s earnings involve that individual stand. The earnings of that stand can be seen as the “small picture” — no less important than the big picture, but only a part of it.

But just looking at individual lemonade stands is not enough. Also important is getting a handle on the macro picture or “big picture” — the investment climate as defined by interest rates and inflation. This is the big picture because it affects all lemonade stands in Lemonville, if not the world.

We have already seen how inflation affects the big picture. But what about interest rates? After all, every time the Fed turns the money faucet on or off by raising or lowering interest rates, it affects the money supply and this in turn affects the cost of money everywhere.

Let’s go back to when the Fed raised rates from 5% to 6%, jacking up the rate on Abby’s car loan and everything else. Not only are borrowers affected by this change, but so are lenders — that is, bondholders. When the Fed starts to turn off the faucet, it restricts the money supply, making money rare and therefore more expensive. Banks lend money at higher rates, passing along the increased rate at which those banks must now borrow money. Other lenders also demand a higher interest rate, seeing that they can charge more when the banks are also doing so. Everyone – from credit card companies to loan sharks to pawn shops – starts charging a higher rate on their loans. So too private lenders (people like George) start demanding higher rates, knowing they can charge the highest interest rate the market will bear, subject to usury laws (laws that restrict interest rates to legitimate levels).

As you recall, George once purchased a 5% bond in Lucinda Lemonade Inc. for $50. If the Fed had raised the federal funds target rate after George’s bond investment, it would affect the value of his bond. The longer the term of the bond, the more it would affect the price. If Lucinda Lemonade were to start looking to borrow more money after the Fed interest rate hike, it would find lenders charging more.

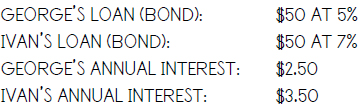

Let’s say that George purchased a 10-year bond, one that gets paid back in a decade. Let’s also say Lucinda Lemonade wants to borrow more money in the wake of the rate hike. Lucinda asks to borrow $50 from Ivan who, keenly aware of the recent shutting of the faucet, demands 7% interest on his 10-year bond. George looks on in astonishment as Ivan gets 2% more interest than he does, just by lending the money a week later. George will now receive $1 less annual interest than Ivan, although they are both lending the same amount to the same company, on the same terms, for the same amount of time:

Hapless George is in deeper than he thinks. Now that Ivan’s bond is identical except for the higher rate, the value of George’s bond has actually declined.

Assume a third lender named Dennis hears that Lucinda Lemonade Inc. is issuing bonds. He grows intrigued, wishing to receive the current juicy 7% interest yield. Meanwhile, George has decided that he actually would like his $50 back so that he can use the money to buy a lemon grove. George approaches Lucinda who sternly wags a finger at him and points to the language in the bond agreement that says George can only get his money back after the one year term of the bond has passed, after the bond has matured. Not easily discouraged, George intercepts Dennis on his way to Lucinda’s and offers him a deal: he will sell his 5% bond to Dennis in exchange for $50, effectively putting Dennis in his shoes. Dennis will now get his stream of interest, and George will have his $50 back.

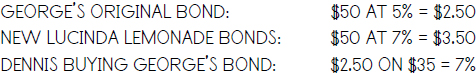

Dennis, no dope, replies that Lucinda Lemonade Inc. is now issuing bonds that pay 7%. Why then, he asks, would he buy George’s 5% bond at all when he could get 7% by buying a new bond? Dennis suggests a solution: he will buy George’s $50 bond — not for $50 — but for $35. This way he will get the same interest stream that George would have gotten ($2.50) but on an investment of only $35, giving Dennis an effective yield of 7%:

George points out if Dennis buys his bond, the bond will pay back its full par value of $50 when the bond matures. Given that kicker at the end, George submits that the exact price at which he should sell the bond is $44.21, the implied present value of the bond, which is a discount that will put Dennis in the exact same shoes as a new bond buyer buying a new Lucinda Lemonade bond at 7%. Dennis agrees and buys the bond.

George isn’t exactly pleased to get back only $44 or so after investing $50, but he takes Dennis up on his offer. He sells the bond for $44, thereby suffering a $6 (or 12%) loss on the value of his bond.

This is another way (along with default, discussed earlier) in which bonds can turn out to be losing investments: when sold before maturity in a rising rate environment. When rates go up, existing bonds lose some of their value since their old interest rates look feeble by comparison. By selling (as George did) before the bond matures, the investor realizes the loss. If George had waited until the bond matured, he would have gotten back his full $50 as guaranteed by contract, regardless of interest rates at the time. But he still feels the pain because he owns a low interest bond throughout a time of high interest rates, which is just a different way of losing.

You will often hear financial commentators saying that bond yields and price are inversely correlated, which is just a trillion dollar way of saying what we just learned: when the yield on new bonds goes up, the price of an existing bond goes down, and vice versa.

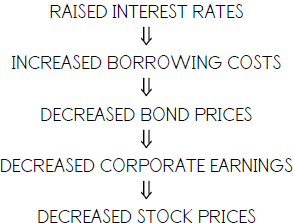

Let’s take a quick look at another result of the Fed rate hike. Back at Lucinda Lemonade Inc., borrowing is becoming more expensive. Each time Lucinda wants to borrow new money, she now has to borrow at a 7% rate instead of the original 5%. She is therefore paying out 2% more in interest than before. That 2% is going to have to come from somewhere. Most likely it will come out of the business profits. All of a sudden, due to a Fed rate hike that Lucinda never saw coming, her business will be less profitable. In other words, her earnings will decrease and her stock price will decline.

The Fed rate hike thereby causes the following chain reaction:

Conversely, a decline in rates by the Fed often causes decreased borrowing costs, increased bond price, increased earnings, and increased stock prices. Such unbridled power from one simple turn of the faucet! You can begin to see what a very powerful faucet it is.

But remember this: no one can predict the direction of interest rates or the economy with any real accuracy, so better to pay attention to value instead. Legendary investor Peter Lynch used to say: “If you spend more than 13 minutes analyzing economic and market forecasts, you’ve wasted 10 minutes.”

“No nation was ever ruined by trade.”

- Benjamin Franklin

If you’re like many a lemonade stand investor, you’re wondering if investment opportunities exist outside the United States. For example, you may have heard that China has over a billion people. That’s a lot of lemonade.

There’s a vast, fertile grove of investment opportunities outside the United States — not necessarily lemonade stands, but many other businesses with solid earnings and strong balance sheets. In fact, 75% of the world’s public companies exist outside the U.S.

Given that so many growth opportunities exist overseas, it makes sense to consider foreign investment and to adopt a global perspective. American investors can easily invest in foreign markets through specialized mutual funds, exchange traded funds, or through American Depository Receipts (ADR’s), which represent shares of foreign companies and are traded in the United States. In addition, some foreign companies list their shares directly on U.S. stock exchanges.

There are special potential rewards to investment abroad. Consider the fact that many foreign countries have faster GDP growth than the United States and much greater potential for future growth. Of course, greater potential reward means greater potential risk. The higher risks of investing abroad cannot be ignored.

We will consider the primary risks of foreign investment in turn: political risk and currency risk.

Political risk is big. Consider for a moment that all investing within Lemonville takes place within the United States. The United States is a constitutional democracy with good protection of property rights, essential building blocks for capitalist investment. Without constitutional rights protecting basic human liberties and property, there can be no such thing as investment.

Imagine, for example, a country where lemonade stands could be confiscated by the government on a whim. That would have discouraged Lucinda’s desire to invest in the table and chairs and lemons to get started. Similarly, it would discourage people like Abby from buying shares in lemonade stands. Who wants to invest their money in a business that can be confiscated? Or in an unstable country with rioting and political chaos? Lucinda would probably think twice before setting up a lemonade stand in such a place, and you would too. Fortunately, there are many countries outside the United States that do respect property rights, and the number is growing by the day. Many European and Asian countries have deeply held protections of private property and represent fertile opportunities for foreign investment. Here, we take such protections for granted, but the reality is that many countries do not set the same standards. Countries that do not protect such rights are not smart places to invest.

The bottom line: do your homework before you invest.

This leads to Lemonade Law #7:

Along comes Abby, flush with her success in the lemonade investment world. Abby feels that international investment would further diversify her investment portfolio. After all, the risks elsewhere might be different from the risks in Lemonville. The differing risks might (to some extent) cancel each other out. Abby’s instincts are right on the money.

Abby researches the island state of Exotica, the home of a thriving pineapple industry. The residents of Exotica are serious about their pineapples and there are many well-run pineapple stores. Abby feels these stores present a good investment opportunity. She finds that pineapple consumption is increasing as the Exotica population increases. Abby reasons that the pineapple business in Exotica is very different from the lemonade business in Lemonville: pineapple selling is not subject to seasonal cycles since people eat pineapples all year round. She feels this factor will especially diversify some of the seasonal risk out of her portfolio.

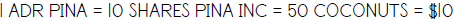

Abby learns that one of the most prominent chains of pineapple stores, Pina Inc, has listed American Depository Receipts (ADR’s) on the Lemon Tree Stock Exchange. Pina Inc. has done so by working out an arrangement with a Lemonville bank by which it deposits 100 shares of outstanding Pina Inc. stock in the bank’s vault. The bank in turn issues 10 ADR’s to trade on the LTSE. Each ADR thereby represents 10 underlying shares of Pina Inc. stock and trades accordingly.

Before buying one Pina Inc. ADR (ticker symbol: PINA), Abby researches the economic and political characteristics of Exotica. After all, Exotica will be the country of her investment, and an analysis of Exotica is as important as one of Pina Inc. itself.

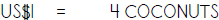

Abby learns that the currency of Exotica is the “Coconut,” and that US$1 currently buys four coconuts:

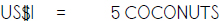

We can therefore say that the exchange rate is four coconuts to the dollar. Most currency exchanges are freely floating, meaning that the rate of dollars to coconuts changes with market demand. In other words, if people are buying lots of dollars and selling coconuts, the value of the dollar in terms of coconuts will rise like so:

A currency rises and falls due to demand, like anything else. It really always does just come down to that simple concept: supply and demand. What’s odd about a currency is that its price is always quoted in terms of another currency, which also floats in price. So if $1 now buys five coconuts (up from four a week ago) it may be that people want more dollars, or fewer coconuts. Or it may be a combination of both.

Now let’s get back to Exotica, where $1 now buys five coconuts. Abby decides to buy one ADR share in Pina Inc. When she purchases the ADR, the price will be quoted in dollars since an ADR trades on a U.S. exchange. Let’s say she buys one ADR share for $10. Thus, the ADR represents 10 shares of foreign Pina Inc stock, valued at $1 each.

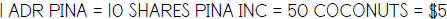

But in Exotica, shares of Pina Inc. are quoted in coconuts, not dollars. One share of Pina Inc. is trading at five Coconuts, which in turn equals $1. And since an ADR represents 10 Pina shares, Abby’s $10 purchase is equivalent to 50 coconuts:

In essence, Abby has invested in 50 coconuts, the exact equivalent of $10. But she doesn’t think in those terms because it’s just dollars to her. The catch is that the investment she made, though on a U.S. exchange, actually resides in Exotica. And her investment will rise and fall in value not just in relation to the economic prospects of Pina Inc., but also in relation to the strength of the coconut.

Assume that Exotica falls on hard times. The once idyllic island state experiences an economic slowdown. As word of the slowdown spreads, foreign investors yank their money by selling Exotica stocks. This panicked pullout causes a chain reaction. When foreigners pull their money, they’re actually converting their cash from coconuts to dollars. Just as someone exchanges Euros for dollars upon getting back from a Parisian vacation, so too do foreign investors exchange their money back into dollars when they sell a foreign investment. When many people sell their coconuts for dollars at once, it can cause a currency collapse, a process by which the currency stops floating and instead sinks.

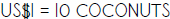

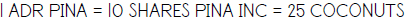

In our example, the problems in Exotica cause the coconut to lose value, declining to a rate of 10 coconuts for every dollar:

Now Abby’s investment is worth only half as much in dollar terms:

If Abby decides to sell her shares now, she will only get back $5 instead of the $10 she invested, due to the decline in value of the coconut, even if the stock price itself stays the same.

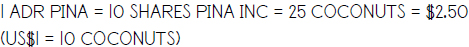

But when the Exotica currency collapses, Abby usually loses in two ways: the decline in the currency and the decline in the stock price. First (as seen above), the decline in the value of the coconut to the dollar causes her investment to decline in value in dollar terms; also, the sell-off in Exotica stocks causes the price of Pina shares to plummet from five coconuts per share to 2.5 coconuts per share. As a result, one Pina ADR (representing 10 Pina Inc. shares) now sells for only 25 coconuts:

The Pina ADR will in turn be priced in dollars:

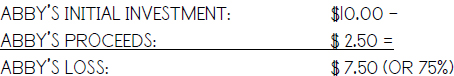

The two-pronged disaster results in a serious loss for Abby. She invested $10 but ends up with only $2.50, a 75% loss on her investment:

As you can see, a decline in a country’s currency can spell doom for foreign investment. There are ways to hedge against this currency risk, but remember Lemonade Law # 4: Hedging may help, but there’s always a cost to it. And a currency hedge is no different. It can be expensive and complex, which is why foreign investment is often best left to a mutual fund specializing in international stocks.