“The art of our necessities is strange that can make vile things precious.”

- William Shakespeare

Some people don’t like to invest in businesses or governments — as either a lender or an owner. They feel businesses are prone to failure, or that governments can’t be trusted. Such thinking would lead them to shun stocks and bonds and look elsewhere. That elsewhere might be commodities, a four-syllable word for “things” with value.

Commodities come in many types: there are gold and silver, wheat and soybeans, crude oil and natural gas. There are even lean hogs and live cattle. All these things can be bought and sold. As you know well by now, the price of these things will depend on supply and demand.

Gold and silver are precious metals. Your gold wedding band is worth something beyond its sentimental value, and that something is largely determined by the weight of the gold in the ring. Gold prices are quoted per ounce. Gold bugs, those who are perpetual optimists about the price of gold, hoard it in the hope that the price will rise. Gold bugs feel that modern currencies will lose value, due to governmental collapse, or rampant inflation, both of which would spur renewed use of gold as a store of value. Gold had its day during the commodity price inflation of the seventies and more recently in the wake of the financial collapse of 2008. Aside from that, gold has been a lackluster investment over the past century, increasing not much more than the rate of inflation. One dollar invested in gold a hundred years ago would now be nearly $100, while one dollar invested in stocks would be over $10,000.

Any commodity is a raw thing, not a business: its value will depend solely on how much of it is needed or desired. Unlike a business, it can’t grow through expanding its business tentacles, nor can it create value or wealth for its owners over time by creatively reinventing itself. On the flip side, it cannot fall flat on its face through poor management or business execution. It is what it is — a thing — for better or for worse.

Some commodities serve a commercial purpose, while others do not. Oil (also known as black gold) is the major industrial fuel, one which you personally demand every day for your car. It’s easy to see why oil has value. As long as people need it, it’s a commodity with significant worth. Oil prices are extremely volatile. Depending on the world’s demand for oil and the available supply, the price of oil changes rapidly. On the other hand, gold has fewer commercial purposes. While it’s used in some manufacturing and is certainly a staple for jewelry, gold does not power cars or fly airplanes.

In the town of Lemonville, many citizens are commodity buyers. Some buy commodities for their own purposes, while others buy for industrial reasons. In Lemonville, the commodity of choice is the lemon. Liam buys lemons for their natural beauty. He collects lemons and mounts them on shelves in his office. As a collector, he has no actual need for lemons and instead buys one whenever he has the inspiration. George, on the other hand, buys lemons as an investment. When he thinks there will be a shortage of lemons, he buys more. George is not one to store hundreds of lemons at home, so he buys lemons through the Lemonville Commodities Exchange, where he’s able to purchase contracts to buy lemons instead of the things themselves. These contracts are much easier to fit in a drawer.

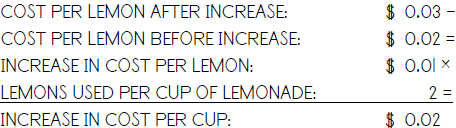

Lucinda buys lemons for her business. Unlike Liam or George, she is not a discretionary buyer: she must buy lemons to make lemonade. When demand increases and the price of lemons rises, business buyers like Lucinda often show a reduction in their profits. This reduction is caused by the higher price of lemons:

Lucinda will have to plunk down two more cents for every cup she makes. Unless she can pass along this increase to her customers by means of her pricing power, she will have to eat the difference herself. Her profit margin on each cup of lemonade will decline by 2 cents.

You can begin to see how increasing commodity prices are considered inflationary. Lemons are a “good” and when the cost of goods rises because demand outstrips supply, inflation results. If many commodity prices were to rise at once (not just lemons, but oil, gold, and everything else), rapid inflation would result. That’s why people often purchase commodities as a hedge against inflation. The owner of a commodity makes money as the price of the commodity increases, so an owner of lemons will profit as lemon prices rise.

Some people think the price of all commodities will just keep rising faster and faster over time as the earth gets more crowded and more people need more things. This simplistic view ignores the fact that the technology to extract commodities improves greatly as well, increasing their availability over time. It also ignores the way in which technology evolves to get more use out of fewer things. Finally, it ignores the way in which people eventually substitute one commodity for another (if possible) or reduce demand when the price rises too high.

If you wish to hedge against inflation, you often have a choice between buying the raw commodity itself (lemons) or the businesses that “make” lemons (lemon growers). Lemon growers are very pleased when the cost of lemons rises: since they are sellers of lemons, not buyers, their profit margins increase on the heels of high lemon prices. A lemon grower can make out very well when lemon prices go through the roof. By the same principle, many people buy stocks in oil companies when they feel oil prices will rise.

There’s a big difference between buying the lemons and the lemon growers. Buying the lemons themselves is an investment solely in the demand for lemons. Lemons can neither expand into new markets, nor can they increase productivity. They cannot grow their business or branch into other sectors. A lemon is a lemon, for better or worse. A lemon grower is a business run by a human being. She can decide to abandon the lemon business and sell pancakes — during a period, for example, when lemon demand is very low. She may also be able to grow her earnings at a rate faster than the demand for raw lemons increases. By the same token, the lemon grower can make tragic mistakes (such as expanding into the pancake business without knowing the first thing about pancakes), while the humble lemon cannot.

The choice becomes a simple one: If you wish to bet on human progress, you will often buy shares in lemon growers. If you wish to bet on human failure, you will often buy raw lemons and wait for a shortage. Both strategies will provide a hedge against an increase in lemon inflation, but one is very different from the other. Over long periods of time, returns on stocks of commodity producers have beaten returns on commodities, leading some to conclude that humans, despite their short-term failings, make progress over time.

“Location, location, location . . .”

- Ancient Real Estate Maxim

Just outside Lemonville sits a beautiful lemon grove on 10 acres. Abby bought it with her remaining savings. She reasons that in a place with demand for lemons, the land that bears the fruit will be a fine investment. Abby has purchased real estate, a good part of any diversified investment strategy.

Real estate can come in many forms. Abby, for example, also owns her home. This is a type of real estate with special advantages. First, Abby’s home is a place to live. You can’t live inside gold bullion and it’s even harder to find warmth in a portfolio of stocks. It’s not bad when your investment provides shelter as well as value. In addition, the money Abby borrows to buy her home, known as a mortgage, is entitled to some special tax savings. Assuming she itemizes her deductions, Abby can deduct most (if not all) of the interest she pays on that loan. The government gives this tax break to encourage home ownership, and it’s best to take them up on this rare display of generosity.

Let’s see how smart it is for Abby to own her own home. Abby bought her house this year for $100,000. She made a down payment of $20,000 and borrowed the remaining $80,000 from the bank by taking a loan to buy a house, a mortgage, for 30 years at an interest rate of 4%:

Abby owes interest of 4% a year on her mortgage, which comes to $382 monthly on the $80,000 principal value of her loan, including both interest and amortization, the gradual payment of the underlying principal over time:

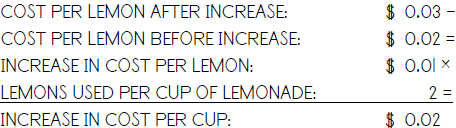

Since Abby can deduct her mortgage interest, she can deduct most of the $4,584 from her income (subject to certain restrictions that are too complicated to explore here). Assuming that Abby has a 35% tax rate and that she can (for the sake of example) deduct the whole payment, we can calculate that her real rate of interest, after the deduction, is equivalent to only 2.6% by using a formula similar to the municipal bond tax-equivalent yield calculation. We use pretty much the same formula but instead of dividing by the tax rate denominator; we multiply it by what we might call the tax rate multiplier.

You start by subtracting your tax rate (expressed as a decimal) from 1.0 to get your tax rate multiplier:

Finally, you multiply the mortgage interest rate by the tax multiplier to get your tax-equivalent rate:

It only costs Abby 2.6% in interest a year to own her own home — pretty extraordinary — and certainly cheaper money than you can find anywhere else. Due to its tax deductibility, a home mortgage is the only “good” debt for most people to have.

This leads to Lemonade Law #8:

You might have noticed that Abby’s mortgage loan is a type of leverage. After all, she has borrowed money and then has gone right ahead and invested it — the very definition of leverage. What makes this type of leverage better than any other? What, for example, makes it better than margin debt?

The big difference is that Abby’s home can’t be sold out from under her if the value declines. For example, if her home’s value sinks from $100,000 to $80,000 overnight, the bank cannot sell the house to seize its collateral the way a broker can seize margined stocks. If Abby were to stop making her mortgage payments, the bank could foreclose on (take ownership of) her home. But as long as she continues to make her payments in a timely way, the bank can’t step in and snatch the house away from her. So Abby controls her destiny in a way that she can’t with a margin loan on stock. In addition, real estate is much less volatile than the stock market: prices are not likely to decline as quickly in any given period.

This is not to say that buying a home is risk-free (always recall Lemonade Law #2). Millions of people have experienced that risk first-hand over the past five years as home prices have collapsed, even below the value of the outstanding mortgages. If, for example, the value of Abby’s home declines below $80,000, her mortgage will be under water, meaning that by selling her home at the market price, she cannot raise enough cash to pay off her mortgage. This is a potentially dangerous situation if Abby has to leave Lemonville quickly: she will not be able to pay off her full mortgage liability by selling her home. If Abby can afford to wait, however, she may be able to sit tight until values return to what she paid.

Be sure to always get a fixed rate mortgage, where the interest rate stays the same for the entire length of the loan. Banks sometimes try to sell adjustable rate mortgages with teaser rates that are very low at first but then can rise much higher over time. These adjustable rate mortgages, or ARMs, can look good at first, but really come back to bite you later.

The leverage contained in a mortgage can be managed. It all comes down to value, as with anything else. If you don’t overpay for a house, it will be a good long-term investment. If you overpay, or borrow too much to buy it, or get the wrong type of mortgage, you’ll end up with a lemon for a home.

“The greatest risk is not taking one.”

- Unknown

Of course, everyone in Lemonville dreams of investing early in that start-up lemonade stand that really flies and makes them rich beyond their wildest dreams. The people who invest in businesses early on (before the companies have gone public) are called venture capitalists. They use money earmarked for risky ventures (venture capital) to invest in young companies that have good growth prospects.

If you recall Liam’s early investment in Lucinda Lemonade, while Lucinda was still a small-time entrepreneur with not much more than a few lemons and a dream, you’ll get the idea. Liam was a venture capitalist (VC) who staked his $10 on Lucinda’s start-up lemonade stand.

It won’t surprise you to hear that venture capital is the riskiest type of investment, with dramatic possibility of both gain and loss. Remember that bigger returns always mean bigger risks, and to generate venture capital rates of returns, you have to take extraordinary chances.

How big are the risks? The average venture capitalist strikes out nine times out of ten, or in other words bats .100 — not exactly major league material but sometimes good enough for the VC. The venture capitalist can expect wipeouts on most investments, but if even just one makes it, the rate of return on the winner can compensate for the losers. Batting .300 would be a success, just as in baseball.

You can see the problem immediately: in a world where it’s this hard to hit home runs, you can run the risk of striking out, where the VC slinks away with an empty wallet and a heavy heart.

The risks of venture capital stem from the nature of the investments. A VC invests in unproven businesses with unproven results. These businesses often have inexperienced management and untested products. There is so much that can go wrong that the VC has to do a lot of research, or due diligence, to separate the good prospects from the bad. In addition, the VC is looking at firms that do not trade on regulated markets. They are private companies, and the watchword is buyer beware. The VC is buying a type of private equity. Buying shares privately offers few protections. It leaves them exposed to one-sided negotiations, inefficient markets, and, at worst, fraud. Liam didn’t really know what he was getting into with Lucinda. She could have turned out to be a flop or, worse, a charlatan. The shares are also illiquid. In fact, they may not be able to be sold at all.

This is not to say that venture capital is too risky. Again, the rewards must be in line with the risks. Great riches are achieved by entrepreneurs teaming up with VC’s to create new businesses. Not only does this process create personal wealth, it also leads to growth, jobs, innovation, and prosperity. This is the core mechanism by which capitalism works. And VC’s play a big part in that role. One thing that makes America great is the personal freedom that allows risk-taking and success.

Because venture capital is so risky, securities laws generally restrict it to those investors with a minimum amount of wealth — in other words, those who are deemed to have the resources and sophistication to evaluate private VC deals. Individuals who invest their own money like VC’s are called angel investors, or angels. Angels normally have to satisfy net-worth requirements to legally invest in start-ups.

Venture capital is the best way to take an outsized risk that can lead to outsized returns because the VC gets in at the start of the business, on the “ground floor,” when a piece of the business can be bought for a relatively low price. Liam was able to buy a tenth of the business for $10, something he would never be able to do further down the road when Lucinda Lemonade was successful. Big risks make venture capital best for wealthy investors who can literally afford to lose whatever they invest. The money put up for venture capital is often called risk capital, which means the same thing but reflects the idea that the money can afford to be lost. No one should ever invest a dime in venture capital that they would need at some point in the future, say for a down payment on a house or for a tuition bill.

“Never forget that only dead fish swim with the stream.”

- Malcolm Muggeridge

It may seem odd to single out any particular stock sector, but technology does merit a separate chapter. Due to their central role in worldwide financial markets, “tech” stocks (especially Internet stocks) have seized the public’s imagination, both on the way up and on the way down. It’s important to take a moment to explain the special risks and rewards of this extremely volatile sector.

What is a technology stock? Presumably, it’s the stock of any company that creates a technology product or service. But there are many subsectors within the larger technology sector: semiconductors, software, cloud computing, Internet, wireless, and telecom to name just a few. The tech sector is necessarily complicated by the myriad of complex business types that inhabit it. What makes most technology stocks so risky (and hence potentially profitable) is that the landscape of technology changes so quickly that planning corporate strategy is difficult. If a tech company zigs when it should zag, profits can collapse as its products become obsolete. An oft-quoted example is the decline in IBM’s dominance as it failed to foresee the shift away from mainframe computers in the 1980s. A more recent example is Apple’s iPhone crushing RIM’s Blackberry. Even buggy whips were high tech until the automobile appeared. The trick with technology is that management (no matter how skilled) cannot consistently predict changes. Technology shifts so quickly and so radically that most tech executives could get the same help from tarot cards as from trend analysis. Warren Buffett is notorious for shunning most tech investment on the theory that he can’t predict changes in the tech landscape and therefore can’t accurately predict cash flows.

Let’s look at tech investment in action. In Lemonville, Lucinda — ever the entrepreneur — has started a new company, Lemonade.com that manufactures high-tech products for the lemonade industry. Lemonade.com designs and manufactures these items and then sells them on their website. As the summer rolls around, they introduce a new app called the Lemon Launcher, which tracks lemon inventory. The Lemon Launcher is an immediate hit because it eliminates the task of counting the lemons at the end of a hot day. Lemonade stand owners place orders for the Lemon Launcher by the thousands, and Lemonade.com looks set to hit record revenues.

George, not one to ignore a hot idea, investigates the Lemonade.com website. He notes the sleek design of the site, the user-friendly approach, and the useful products. He purchases a Lemon Launcher for Meg as a gift. George is impressed by the reasonable price and the good reviews. George considers buying some Lemonade.com stock as an investment. But George is a more educated investor than he used to be. He made some big mistakes early on, and he has vowed to do more research on future stock picks. So George reviews the recent annual report of the company and is pleased to see that cash reserves exceed total liabilities (what the business owes), a sign of financial strength. George also talks to a few people in the industry who rave about Lemon Launcher and predict astronomical sales growth. George knows a good thing when he sees it. He doesn’t hesitate: He buys 10 shares of Lemonade.com (LMDC), paying $5.50 per share.

At first, George is elated. LMDC doubles in price on word of brisk sales. Rumors abound that LMDC will soon be bought by a large Internet company. The blogosphere swells with ecstatic postings touting the infinite potential of the Lemon Launcher. Soon, unscrupulous stock promoters exaggerate claims of earnings growth in order to pump the stock. LMDC doubles in price again. George’s shares are now worth $220. As the price rises, George grows a little nervous. He’s been burned before, but he decides to hold onto the stock because it just keeps rising. Besides, LMDC has a virtual monopoly, and there’s no end in sight to the demand for the Lemon Launcher. He pictures a global village littered with Lemon Launchers, where every lemonade stand owner in the world — not just Lemonville — tracks lemon inventory automatically. He also indulges in a quick daydream: if the price doubles twice more, he’ll be able to buy a Lemonborghini, the most luxurious vehicle in Lemonville.

While George plots his joyride, a small company named Lemonlover Technologies is working feverishly to design a competing app. Lemonlover Technologies plans to give theirs away for free while making their money on ads instead. This all occurs unbeknownst to George who occupies himself with monitoring the stock price, not the underlying moves of the competition. As soon as Lemonlover Technologies announces the arrival of their competing product, LMDC stock takes a big hit. It becomes clear that LMDC has lost its virtual monopoly and earnings estimates will have to be revised downward. The Lemon Launcher has regrettably reached that special state of purgatory: it has become a commodity product, a cookie-cutter type of thing that can be produced cheaply by anyone. By releasing a competing version quickly and cheaply, Lemonade Technologies has shown that the Lemon Launcher’s barrier to entry (the “gate” preventing imitation products) is woefully low.

Barriers to entry are beautiful things for technology companies with complex products. A tech company that owns a patent on an especially unique device, for example, can hope to maintain a virtual monopoly for a long time. A designer of very sophisticated equipment, even without patent protection, can hope to ward off competitors via its proprietary technology - its secret bag of tricks. But if an item is simple to manufacture, it will spawn immediate imitations, and the product will become commoditized. Once a product becomes commoditized, prices drop and profit margins decline. This set of circumstances can spell tough times for a tech company.

But the last straw for a technology company stems from obsolescence, not commoditization. Imagine that Lemonlover Tech develops an app called the Lemon Love Child that not only monitors lemon inventory but also replaces that inventory by automatically ordering more lemons. Soon, every lemonade stand owner is buying the Lemon Love Child and using it to run their business. The Lemon Love Child literally destroys LMDC’s business: no one wants to just count lemons without ordering more. LMDC’s stock plummets to $1, a level at which it faces being delisted from the LTSE. George kisses his Lemonborghini goodbye.

Notice how George’s problems could have been avoided through one of two methods: research or diversification. Tech investing requires one or the other, preferably both. After all, the best answers to high-tech problems are often low-tech solutions.

“The odds are good but the goods are odd.”

- Alaskan Saying

A quick route to diversification is through a fund, a basket of diversified investments. A mutual fund is a type of fund that is well-regulated in order to protect its investors. By purchasing shares in a mutual fund, the investor is actually purchasing a stake in the underlying holdings. Mutual funds can invest in many different types of investments: stocks, bonds, commodities, etc. A mutual fund is not an asset class in and of itself; rather, it’s a pool of money that can invest in many different types of underlying assets classes, such as stocks or bonds.

An exchange-traded fund (ETF) is a similar diversified pool of investments, just like a mutual fund, except that it trades freely during the day on a stock exchange, making it easy to buy and sell. ETFs often have lower costs than mutual funds, making them the single best option for most investors.

An index fund or index ETF tracks an index, an unmanaged group of stocks or bonds. It does not try to pick and choose investments. Rather, it buys the stocks in an index, such as the S&P 500 Index, which is a collection of the stocks of 500 major companies. An index fund has certain distinct advantages: it usually has a low expense ratio and high tax efficiency, making it a good, low-cost alternative for many investors. If you invest in an index fund or index ETF, you’ll never lag behind overall market returns. Conversely, you will never beat the market either. The disadvantage of an index fund is that it’s essentially unmanaged. With an index fund, there’s no decision-making authority. In fact, there is no decision-making. If investing in actively managed funds is like putting your investment plane under the control of a pilot, investing in an index fund is like putting that same plane on automatic pilot: It will run smoothly most of the time, but would you want it steering you through a crash landing? Even an automatic pilot is better than a bad pilot, though.

Mutual funds and ETFs have advantages beyond instant diversification: (1) they are regulated, lending them a measure of safety; (2) they are transparent vehicles that can be tracked and evaluated clearly; and (3) they are professionally managed, often by experts with long-term audited track records. ETFs are the more transparent of the two and their costs are substantially lower.

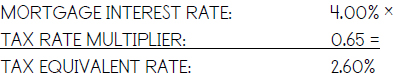

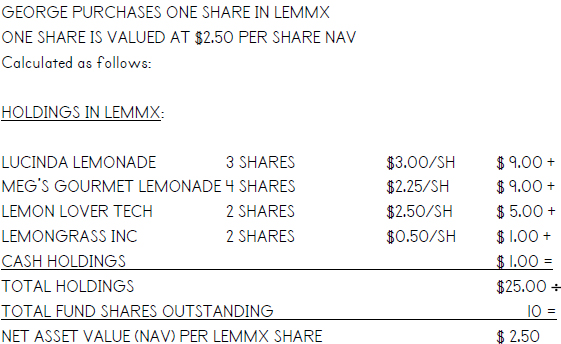

Imagine that George wises up after his tech stock travails. He wants to hire a professional manager to pick his Lemonade tech companies. For this purpose, he chooses a mutual fund called the Lemonade Mix Fund. In order to invest, he purchases shares in the fund, just as he would in a stock. The fund has a ticker symbol just like a stock: LEMMX. The difference is that he purchases these shares at a price — called the net asset value (NAV) — that represents the value per share of the combined assets in the fund:

In reality, a mutual fund would own many more holdings and thus be far more diversified, but you get the idea. This group of holdings is called a portfolio. By buying a share in the mutual fund, George is purchasing a piece of this portfolio and all the underlying holdings within. An ETF works roughly the same way, imparting instant, low-cost diversification to the buyer.

The Lemonade Mix Fund is managed by Peter, a professional money manager. Peter buys and sells the stocks in the funds based on research he conducts. Peter is an expert in the lemonade sector and keeps abreast of industry trends. By keeping his ear to the ground of the lemon grove and studying financial statements, Peter often avoids catastrophe. For example, he spurned shares of Lemonade.com: having heard of Lemon Lover Technology’s ambitious plans, he suspected the Lemon Launcher would quickly become commoditized. In addition, Peter extensively reviews all company balance sheets to make sure that only well-capitalized companies find their way into his portfolio. Of course, there’s no guarantee that Peter will do a good job. But the combination of diversification, regulatory oversight and professional management reduce (but don’t eliminate) the chance of a permanent catastrophe.

There are disadvantages to mutual funds. They are required to pay out capital gains distributions on a regular basis, passing a tax hit along to their investors. This doesn’t matter in a tax-deferred or tax-free account. In a taxable account, however, it pays to evaluate the fund’s tax efficiency — the percentage of gains the investor keeps after taxes. By resolutely screening for tax-efficient funds, an investor can eliminate excessive tax bills. ETFs are usually more tax-efficient than mutual funds, due to their indexed approach. Mutual funds and ETFs also pass along their management fees and operating costs along to the investor in the form of an expense ratio, the percentage of overall assets that is charged in annual expenses. Investors should screen for low expense ratios in order to lower their costs.

When evaluating mutual funds and ETFs, an investor should always carefully review the fund’s prospectus, or offering document. An investor should also consult a third-party rating service. Morningstar provides good, objective analysis of individual funds, including statistics on tax efficiency and expense ratios.

An investor should always review the long-term performance history of a fund (defined as a period of time of at least three years). Any smaller window of performance is subject to distortions and old-fashioned randomness. Be wary of outsized performance gains in any short period of time. These often reflect unnatural sector-specific gains that might not be repeated. Due to the law of averages, the best performing fund one year is often the worst performer in the following year. Many would-be fund investors chase last year’s winner only to end up with this year’s loser. Steer far clear of leveraged ETFs, which borrow money to enhance their returns. These are very dangerous and should be avoided at all costs.

Finally, it’s imperative to review the strategy of the fund to determine if it trades actively or uses hedging strategies. Most important, be sure to understand the fund’s techniques for managing risk. Does the manager screen all securities by the balance sheet?

Mutual funds and ETFs, like all investments, must be reviewed on a regular basis (at least quarterly) to track the fundamentals and review the underlying holdings. Don’t assume that your fund will still resemble the one it was last quarter. Managers get fired or retire and portfolios change. Funds have tremendous advantages if used properly and reviewed carefully. But there’s always homework to do.

This leads to Lemonade Law #9:

Another type of fund that gets a lot of press is the hedge fund. Not all such funds “hedge” their bets, despite the misleading name. When people speak of hedge funds, they’re usually speaking of unregulated private investment funds. In fact, most hedge funds are only available to millionaires by law, putting them beyond the reach of average investors. Within the broad misnomer “hedge fund,” there are many types of funds, some of which use hedging techniques, some of which don’t. Due to their unregulated nature, hedge funds can do things mutual funds can’t — sometimes a blessing but often a curse. Many hedge funds use excessive leverage, trade actively, lack transparency, and employ esoteric strategies. Some are very good, while most are not; some have enriched their clients remarkably, others have ruined them recklessly.

The bottom line: when buying into any type of fund, it’s still essential to do your homework.