AIN’T NO USE: INSTANT WEALTH AND THE FRAYING OF THE AMERICAN DREAM

Why work hard when you could just, all at once, instantly become wealthy?! Why wake up early, punch the clock, work all day, punch the clock, unwind all evening, and then punch the alarm clock to do it all over again? Why spend the majority of your life toiling away just to pay the bills if you could, simply and magically, instantly become wealthy?

I am by no means an expert on and am, in fact, barely a consumer of popular culture in the United States. By the time I notice a pattern in popular culture, it is safe to assume it has become passé. So, please indulge this beginning with the banal and passé: the fantasy of instant wealth has become a regular mantra in cultures under the sway of neoliberal social rationalities. It seems clear, as we enter the mid-2010s, that US popular culture has been creating and widely disseminating the dream of instant wealth as an escapist fantasy of pure wish fulfillment for over two decades. Unlike the exception that has always haunted—and thereby also proved—the rule of liberalism and its mandate of the Protestant Work Ethic, the fantasy of instant wealth has transformed in neoliberal social practices into a widely circulated

possibility. No longer just those crazy gold diggers headin’ west, we neoliberals seem to believe that it is possible to become, all at once and with no effort, instantly wealthy. Or, at least, we like to watch and read and talk about this narrative a great deal: we enjoy the fantasy.

As with any widespread cultural phenomenon, there are many ways to interpret this ascendancy of instantaneous wealth as a possibility that various populations seem to believe is a viable moment in their individual lives. Read ideologically, for example, it can be understood as the kind of pernicious duping of the downwardly mobile middle class and working poor that politico-economic systems of neoliberalism wreak. This certainly offers insight into one aspect of the sociopsychic and material effects of the intensifying income disparities caused by neoliberal economic and political reforms. But it does not account for how and why people living in cultures where neoliberal social rationalities are circulating find this particular fantasy so alluring. The explanation that we are just grossly duped by hegemonic structures leaves subjectivity rather infantile, constantly tricked and confused into wanting things that the authorities make us think we want.

If Jodi Dean’s extension of Foucault’s analysis captures some crucial aspect of the transformations underway, then we need an analysis of this fantasy that does not position us as infantile subjects of desire.

1 Pursuing our interests kinetically, we need an explanation that does not fall back into the orders of the symbolic. We need an explanation of how and why we are so cathected to the fantasy of instant wealth. But, to foreshadow the Lacanian lexicon in which I undertake these analyses, we need to examine how this distinctively neoliberal fantasy functions in the register of the drive, rather than desire, where classically liberal fantasies cathect subjects with deep interiority.

Eerily, if also unsurprisingly, this fantasy of instant wealth manifests differently according to racialized dynamics that are very similar to the social effects of utility in cultures of classical liberalism (which I examined in

Queering Freedom). The lure of the ostentatious, utterly over-the-top wealth of rap, hip-hop, and sports stars speaks differently—that is, receives and generates different cultural representations—than the ostentatious, utterly over-the-top wealth of college-educated, geek entrepreneurs or savvy investors. The life story of Mark Zuckerberg spun by the media is, for example, quite different from the kind of story of aberration that attaches to figures such as Snoop Dogg or 50 Cent. These differences matter, particularly as the differing kinds of displays of this wealth belie the persistence of long-standing racialized schemas, while simultaneously instantiating new ways to modulate them. But it is the formal sameness of the fantasy itself that I want to examine before turning to what it tells us about persistent racism in new, neoliberal racializing schemas.

I argue the fantasy of instant wealth offers a cultural representation of the neoliberal subject of interests as inhabiting a Lacanian circuit of the drives, wherein instant gratification, not the delayed anticipation of desire, animates activities. We love the fantasy of instant wealth because it is the direct effect of pleasurable activity, not the hard-earned, well-deserved satisfaction of good, honest labor and orthodox education: these neoliberal icons are so fabulous because they get instantly wealthy by simply doing what they love, by simply having fun, by simply enjoying themselves—over and over and over. As an instance of the shift from desire to the drive, from the subject of rights to the pursuer of interests, the fantasy of instant wealth simply eschews any social cathexis to utility, that sacrosanct value of liberalism. Again, in the Lacanian terms that I develop in this chapter, this precious objet a (utility) of liberalism’s fantasy of neutrality loses its mooring in this dream of instant wealth and the desiring subject itself begins to fade from the neoliberal iteration of the modern episteme.

Once more performing what Husserlian phenomenologists might call an eidetic reduction, I bracket the racialized manifestations of this fantasy of instant wealth in this chapter to focus on its formal structure. First, I develop Jodi Dean’s provocation that subjective formation in neoliberalism is structured by a shift from desire to the drive, emphasizing particularly how this manifests in a systemic move toward formalizing social difference itself. I then remain in a Lacanian analytic and frame liberalism through the psychoanalytic concept of a fantasy, arguing that cultures of liberalism are structured by the doubled fantasies of tolerance and neutrality.

2 I then return to this neoliberal fantasy of instant wealth to show how the neoliberal waning of the social cathexis to utility reverberates in alterations in the social cathexis to xenophobia, especially racism, and its structuring of social difference; accordingly, the doubled fantasies of neutrality and tolerance are also undergoing profound transformations. I conclude the chapter with a discussion of the implications of these transformations for meanings, modes, and cathexes to normativity in the neoliberal social rationality of calculation, especially in the exemplar of statistics, and the transformation of concepts of social difference into units of fungibility. While this is also not a particularly cool chapter, it is only after clearing this ground that I can begin turning toward rethinking race as the real.

CIRCUIT OF THE DRIVE AND FANTASY

Given Foucault’s analysis of the overlaying and (at least) partial displacement of liberal modes of subjectivity and rationality by neoliberalism, neoliberal subjects do not lament the loss of an internal, juridically structured script. While it may be true that those modes of liberalism are not wholly displaced, while it may be true that we do still have some (albeit largely habitual and often desperate) recourse to transcendental foundations and juridical structures, the effect—especially the social cathexes—of such recourse is considerably weaker. Foucault’s insistence that neoliberalism does not function as an ideology and his excavation of this “subject of interests” thereby give us a provocative way to approach this new social landscape, where we live in states of heightened stimulation that no longer fully succumb to the psychosocial force of Althusserian interpellation, the dominant lens through which post-Hegelian social theorists have understood subject formation, difference, and ethics.

The Lacanian schemas of the drive thus further enhance Foucault’s analysis of these new social formations. Unlike ideological critiques of advanced capitalism, a Lacanian analysis of neoliberalism that derives from “the later Lacan” of the drive and the real avoids the naïve critique of consumerism as a classic instance of “chasing the phallus.” We do not have to read the endless quest for cooler and newer stuff as a Marxist affirmation of alienation or as, in Freudo-Lacanian terms, an endless pursuit of fetishes to hide over the fundamental lack that marks all subjects in a phallocentric symbolic. The reading of neoliberal enterprising practices as enacting the circuit of the drive shows us how these practices of consumerism are, in and of themselves, quite satisfying. Practices of self-fashioning become practices of freedom in neoliberalism. The infinity of the endless quest for cooler and cooler stuff—and cooler and cooler selves—is precisely what sets subjectivity into play. Only a symbolically interpellated subject, still bound to the logic of wholeness, would find this infinity pernicious. To the contrary, for the neoliberal subject of interests, the endless proliferation of interests is precisely the play of subjectivity: the more you can intensify your interests, the more expansive, enterprising, and interesting you are. And the more you can stuff your mouth!

3As this endless calculation of interests becomes an obsessive social rationality, it aims to absorb all aspects of living into a flattened horizon of endless accumulating and enhancing of interests. It thereby comes to function as a circuit of interests that, as the heuristic of Lacan’s circuit of the drive accentuates, floats freely across the surface of relations without any social, historical, or ethical anchor. Whether our interests bolster a democratic or fascist state, whether they render us vulnerable or secure, whether they sustain social relations or enhance an isolated egoism is all beyond the purview of our pursuits. We are interest-seeking beings, purely and solely. And because we are such, the Law as a grand interdiction that regulates the dual functions of prohibition and transgression fails to engage us. To lament this loss is understandable, perhaps even necessary as a crucial memorial to the historical structures under erasure. But it is ultimately insufficient: nostalgia is just another quaint accessory, transformed into the coolness of “retro” through the neoliberal evacuating of historical signification.

As I discussed in

chapter 2, Jodi Dean therefore argues that neoliberal subjects of interests respond primarily to the Lacanian register of the imaginary, wherein social controls cathect subjects through the endlessly comparative process of idealization, not authority. We are constantly comparing ourselves to ideal egos, aspiring to be more and more like them—only to find that this process repeats itself endlessly. For Dean, this initiates astute readings of how easily and subtly neoliberal subjects are thereby manipulated politically. Wholly externalized, we neoliberals are at the mercy of whatever political winds are blowing. Dean’s extension of a

Ži

žekian articulation of this in Lacanian registers emphasizes this move from the symbolic to the imaginary as the fundamental shift in political dynamics. I do not disagree with Dean’s analysis, but I am interested in a different social register and, accordingly, a different psychosocial dynamic, namely, the ethical and our processes of cathexes, especially to social difference. Therefore, I take up her provocation that neoliberal subjects inhabit the Lacanian circuit of the drive to examine how this intersects with the fraying of two mutually constitutive ideals of liberalism: neutrality and tolerance.

To do so, I stay in a Lacanian mode of analysis and frame these two ideals as core, constitutive fantasies of classically liberal cultures. By reading the neoliberal social rationality as an eclipse of symbolic authority, I do not want to go so far as to claim that there are no longer any shared cultural scripts or narratives that bind subjectivities to one another, to one’s self, and to a (variegated) social fabric. The claim that the neoliberal social rationality, especially depicted as enacting the circuit of the drive, erodes symbolic investiture does not go so far as to suggest that we are no longer partaking of socially shared and scripted narratives. As a culture filled with endless subcultures, we certainly continue to have common cultural referents that bind and unbind, include and exclude, and generally cathect us to specific objects, experiences, and bodies. But in my insistence that this is not happening according to logics of interpellation, I must find some way of explaining these dynamics without recourse to the kind of juridical law that unifies and formalizes authority in symbolic interpellation. Therefore, I turn now to the structures of fantasy to begin cultivating ways to understand this neoliberal kind of social cohesion and the subjectivity it spawns.

By reading neoliberal subjects as existing in the circuit of the drive, we first need to understand how neoliberal practices and values supplant older teleological stories of pleasure as satisfaction. One of the most striking features of the drive, in Lacan’s texts, is its circuitous, adamantly ateleological structure. The drive, unlike desire and demand, with which it is closely paired in Lacan’s etiologies, does not aim at any object of satisfaction. Structurally ateleological, its circuitous form enlivens repetition, rather than arrival, as the form of pleasure: at a physiological level that risks literalizing, it is the circular structure of the mouth, the ear, and the anus that renders them physical sites of intensified stimulation and thereby exemplars of the circuit of the drive.

4 Repetition in Lacan’s account of the drive connects it back to Freud’s theories of the death drive, which is always distinguished as “pure repetition.”

5As a closed circuit, however, the drive begs the question of its relation to social context. First of all, as Dylan Evans emphasizes, the specific kind of cathexis animating the drive is, at the level of the individual, extremely variable and contingent on the life history of the subject—so much so that it might be rendered impervious to social forces and formations. Whether one is orally, scopically, or anally cathected may, etiologically, be mostly determined by one’s individual experiences in the very early stages of life. When I follow the suggestion that neoliberal cultures are functioning at the level of the drive, however, I am not attempting this kind of etiological analysis; I am not, that is, attempting a kind of pseudo-Hegelian diagnosis of the grand development—and, inevitably imported into such accounts, lamentable regression or fixation—of culture as read on the model of individual development. Nor am I laying claim to the Freudian schema that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny at the level of individual and cultural development. Rather, I am using Lacanian formulations as generative heuristic devices: what kinds of possible readings emerge out of this framing of a neoliberal culture as living in the circuit of the drive?

From this angle, it is less the variability of specific cause, content, or kind of drive than it is the formal properties of the drive as a closed circuit of endless repetition that generates insights into how neoliberal social subjectivity functions. As a closed circuit, the drive can never be synthesized into any greater whole; for example, as a sexualized experience, the circuit of the drive renders sexuality as partial, never harmonized into any whole—whether of identity, self, relationship, cultural or religious ideal, and so on.

6 As a closed circuit, the drive is not structurally connected with any symbolic investiture of personhood or transcendent cultural ideals. This does not mean, however, that the drive is not functioning within a social context. In an effort to elaborate how sociopsychic cathexes alter amid the historical overlaying of neoliberalism across liberalism, I develop the heuristic of a Lacanian account of how drives intersect with, diverge from, and resist the form and formation of fantasy.

My use of fantasy, accordingly, draws on the psychoanalytic development of it as a socially articulated framework that conditions our individual making of meaning. Unlike pedestrian connotations, wherein fantasy connotes those aspects of one’s internal psychic life that are either unhinged from (“escapist”) or compensating for (“wish fulfillment”) the strictures of “reality,” my psychoanalytic approach uses fantasy to connote a socially articulated set of values or ideals that do not function in fully conscious, rational, or linear manners. Unlike the obfuscations that concepts of hegemony and ideology claim to explain, however, fantasies cannot be properly located in any specific site or structure. While still allowing the differentiation of individual from social fantasies, the psychoanalytic concept of a social or cultural fantasy introduces a socially structured epistemology that does not rely on the central roles of authority and identification that render ideological interpellation insufficient to examine cultures of neoliberalism.

For psychoanalysis, fantasy operates through the cathexes it offers with particular values, hopes, and aspirations. Whether one’s individual fantasy clashes or aligns with the constitutive fantasies of one’s culture determines the value of that individual fantasy. If the fantasies align, they are seen as core, shared values of a society, scaled to whatever size (family, neighborhood, corporation, city, region, nation). If they clash, the individual’s fantasy will be maligned as “escapist” or even “deranged,” depending on the magnitude of the threat to the culturally cathected fantasy. (For example, in racialized terms, unaligned fantasies about race in the United States can range from “idealist” to “bigot.”)

By using the psychoanalytic structure and concept of fantasy to read the emergent social rationalities of neoliberalism, I can develop a psychosocial taxonomy of the transformations in social cathexes underway in cultures of neoliberalism. As I have already developed, I situate neoliberalism as part of a fugue, wherein it layers upon and intensifies particular aspects of liberalism. The psychoanalytic framework of fantasy allows us to see how social cathexes to the shared, regulative values of classical liberalism—namely, tolerance and neutrality—are transforming in the neoliberal embrace of entrepreneurialism and diversity.

In order to analyze neoliberalism in this manner, I first examine how these twinned fantasies of classical liberalism (tolerance and neutrality) serve as a necessary condition for an individual to make meaning of his or her experience, both immediately and reflectively. Unlike the kind of cultural authority schematized in ideological interpellation, the fantasy serves as the interpretive background that remains unsaid.

7 It does not require constant repetition to enact its values; au contraire, it functions most forcefully when unspoken, fading into the naturalized glow of the communally assumed, unnoted because so fundamental. The structure of this kind of core fantasy helps us to see how the most forceful of a culture’s values are (as Nietzsche indicated so long ago) those that remain unsaid—until punctured or challenged or exposed.

8It will finally be those moments of and dynamics involved in puncturing, challenging, and exposing that show us what is happening in the shifting social cathexes and evaluations underway in neoliberalism. In Lacanian terms, the kinds of intensifications underway in neoliberal practices expose the objet a of the fantasies of liberalism, thereby bringing them out of the background and transforming their functions.

THE DOUBLE FANTASY OF LIBERALISM: NEUTRALITY AND TOLERANCE

In Lacan’s schema of fantasy, the cause of desire (

objet a) subtends fantasy precisely by never coming into full or explicit view as a part of that fantasy. Unlike the phallus that exerts its power through its invisibility, the

objet a must remain always fully “off-screen.”

9 Think, for example, of the ways that a certain look, a tone of voice, an eroticized body part, a particular gesture or—especially in neoliberalism—a distinctive sartorial flair incite desire: utterly formal, these

objet a expose the essentially impersonal character of desire. It is this utterly formal character that makes the function of fantasy particularly generative for grasping the social cathexes operating in neoliberal social spaces, although the shift from the scene of desire to the circuit of the drive considerably alters the structure of the fantasy and its cathexes with the social body, as I will show.

Reading liberalism in the schema of fantasy, I begin with what is, by now, an obvious set of claims from all ideological quarters. Whether celebrating, defending, critiquing, or protesting against liberalism, all share a common set of assumptions: liberalism sets itself apart from both autocratic and oligarchic regimes through the distinctive claim to both neutrality and tolerance. From classic theorists of liberalism to its various modern instantiations, the grand claim to neutrality as a political and economic system, most often spoken through such quintessentially neutral values as equality and rights, grounds liberalism’s claim to be the best possible kind of politico-economic system.

10 Simultaneously and especially, although not exclusively, in the United States, liberalism also prides itself as upholding the virtually sacred value of tolerance, framing itself as the political system that can accommodate all kinds of social difference.

Over the last three decades, the scholarship on classical liberalism has disabused any simple faith in these claims. For example, as the work of Charles Mills shows, the contemporaneous projects of colonial violence and its institutionalizing of slavery are not merely historical coincidences to the rise of liberalism; to the contrary, the violence used to conquer nonwhite races and thus render them socially inferior found direct purchase in the conceptual framework of classical liberalism.

11 The twinned values of neutrality and tolerance carry a long history of obfuscating persistent and systemic violence committed through the disavowals that they perform. By framing these twinned values—neutrality and tolerance—as the doubled fantasy of liberalism, I can examine the structure of these distinct, although mutually constituting disavowals. It is the processes of these distinctive disavowals that neoliberalism as a social rationality is disrupting, thus precipitating profound transformations in both cathexes to social difference and the precipitated modes of evaluation known as “ethics.”

The framework of a Lacanian fantasy thus not only amplifies the fantasmatic (and thus forever vulnerable) character of liberalism’s long-standing, historical claims to racial and cultural superiority, but also helps us to see more precisely how the crucial fealties to the universality of neutrality and tolerance occur in a sociopsychic register. The important scholarship initiated by Pateman and Mills aims to disrupt liberalism by exposing the horrible ruse of liberalism’s mythical status as neutral and tolerant. But such a direct, largely abstract exposure of these systemic histories of xenophobia does not seem to disrupt the liberal fantasy of superiority. Because the fantasy works precisely through the languages of neutrality, it always already has a defense against these charges in place.

12 The scholarship of historical exposure thereby offers crucial evidence for the systemic xenophobia, but falls short of interrupting the power of these twinned values (neutrality and tolerance) as doubled social fantasies with intense social cathexes. Exposing these as myths, as fictions, as untrue to historical facts does not dislodge the profound cathexes they enact. Ironically, perhaps, it is the social rationality of neoliberalism that performs this sociopsychic labor: it transforms and dislodges the long-standing social cathexes to both neutrality and tolerance.

Following out the Lacanian schema of fantasy, then, I position neutrality and tolerance in relation to their respective

objet a, namely, utility and xenophobia. In what follows, I will argue first for how these are the constituting and forever “off-screen”

objet a of the two fantasies, respectively. Given the preponderance of scholarship on liberalism and race and racism, particularly the focus on the vexed value of tolerance, I will only sketch how the fantasy of tolerance cathects through the

objet a of xenophobia briefly and then turn to the fantasy of neutrality’s cathexis with the

objet a of utility at greater length. While scholars such as Jodi Melamed have begun to turn directly to how the concept of race is transforming in neoliberalism, I argue that we must also attend to the transformations in the mechanics that allow for the social value of paid over unpaid labor in neoliberalism if we are to understand how the dynamics and concepts of social difference are altering in neoliberalism.

13 While my work here on the fantasy of tolerance will become germane to and continue to expand in

chapter 5 and its focus on race, I argue that the transformations in the pairing of neutrality and utility are actually at the core of the alterations we are currently undergoing: when we no longer cathect with utility, our cathexes to the standard liberal concepts of social difference begin to fray, coming undone in unprecedented and sometimes frighteningly unstructured way.

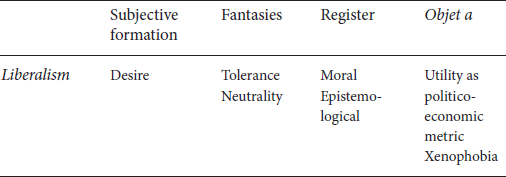

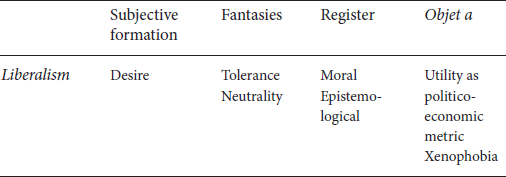

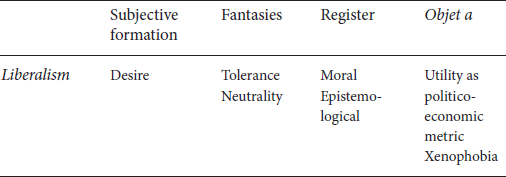

To help keep these various structures and categories clear, I once more offer a table (see

table 3.1), which will expand, as a heuristic.

As Wendy Brown has so forcefully argued in

Regulating Aversion, at the heart of tolerance lies repugnance. The very meaning of tolerance implies the overcoming of disgust, the effort and toil to forgo one’s visceral revulsion in the name of some higher moral ground. Like its cousin, altruism, tolerance finds purchase in classical liberalism’s command to cloak all claims to superiority in the language of moral sentiments. The crucial embrace of tolerance as a distinctive, core, unassailable value of classical liberalism thereby grants an esoteric vocabulary to the shared but unspoken assumption of cultural superiority.

TABLE 3.1 The Structure of Liberalism’s Core Fantasies

In the language of a Lacanian fantasy, liberalism animates the fantasy of tolerance as the hallmark of its moral superiority only on the condition of its ongoing cathexes to xenophobia, which is crucially circulating, as the constitutive

objet a, “off-screen.” That is, according to the structure of fantasy, while it must exalt the value of tolerance as the foundation to its moral superiority, liberalism can only subtend this fantasy through its grounding cathexis with its

objet a, namely, xenophobia. The historically repeated and ongoing coincidence of this exaltation of tolerance and systemic, xenophobic state violence is not a mere ideological contradiction or slippage. It actually animates the fantasy: xenophobia cathects the fantasy of tolerance. Taking the United States as an example, whether eighteenth-century settler colonialism, nineteenth-century chattel slavery, or twentieth-century neocolonialism and racism, it is only insofar as cultures of classical liberalism encounter(ed) social difference as threatening and fearful that the fantasies of tolerance as moral superiority were put into play. But as fantasies, this originating cathexis can never surface, can never come fully on-screen, can never be fully admitted or viewed, lest the fantasy come apart.

14While the fantasy of tolerance serves as a moral screen to the systemic xenophobia of liberalism, the fantasy of neutrality functions as its epistemological counterpart. Not a readily recognizable moral claim, neutrality serves as the bedrock epistemological condition of possibility for the objectivity that grounds virtually the entire system of liberalism. It is what allows liberalism to deflect any charges of bias back onto the minoritarian plaintiffs. Neutrality defines the exalted realm of judgment to which reason, when purified of all subjective bias, ascends. Accordingly, given the enormous difficulties of securing entrance to this sacred realm of neutrality, the purification rites fall primarily to one institution: the law.

Through its labyrinthine logic of precedents, the legal institution of liberalism becomes both the protector and the arbiter of neutrality. Assuming neutrality as the point of departure secured through the historical heft of precedents, the default view of the law is to place the burden of proving the neutrality of any and all claims before it, especially those on behalf of “difference.” As the work of critical race theory, particularly the theory of intersectionality that it helped to spawn, has showed for so long, this systemic assumption of neutrality makes the law a very difficult, if not impossible, site at which to secure judgments in favor of social differences, particularly as they are materialized in pluralized, “intersecting” ways. That is, this systemic assumption of neutrality makes the law an impossible site at which to secure judgments that affirm and enable minoritarian claims for differential treatment before the law.

15The default of the law, working in and through neutrality, is to mitigate against such differential treatment—to protect “citizens” as neutral bearers of legal rights. Differential treatment is thereby always already positioned as a flaw that must be corrected by the law, most often by pitting one faculty of the law against another—for example, exerting legal judgments against biased acts of the police (in its many guises).

16 But this apparently endless self-correction by the law is framed not as a problem of the law’s fundamental assumptions, but rather as a flaw of human nature and its inability to act consistently with pure rationality. Neutrality is the secured, if precarious, realm of the legal system, but it is always an aspirational state of reason for human actors.

Framing neutrality as a core, constitutive fantasy of liberalism opens a more general perspective on its function in cultures of liberalism.

17 First of all, while the law remains, undoubtedly, one of the most intensified sites at which the ongoing tensions between neutrality and difference are negotiated, it does not (thankfully!) saturate our lives in cultures of liberalism and neoliberalism. Taking into account the racialized, sexualized, and classed stratifications of the social fabric, I still contend that none of us lives in constant interface with the myriad forms of the law, despite its best, disciplinary efforts. Secondly, the critical legal interventions regarding social differences such as race and sexuality all too often land in a gridlock that is enabled by this apparently impervious epistemology of and fealty to neutrality. This gridlock gets chalked up all too easily as ideological and thus as a matter of politics. By insisting that neoliberalism is transforming our processes of subject formation, concepts of social difference, and modes of evaluation, I also insist that we must develop critical interventions that do not draw on the epistemologies of the law or ideology. We need as many epistemologies as possible to grasp the often dizzying changes before us; the efforts offered here are but one of many possibilities.

Casting neutrality as a core fantasy of liberalism, then, I contend that it is cathected by the

objet a of utility. This fantasy operates quite differently, however, from the explicit disavowal that cathects tolerance to xenophobia. First of all, utility is itself a dominant value of classical liberalism, extolled by John Locke and glorified in the United States as the Protestant Work Ethic. Rather than an ugly secret that fuels an esteemed moral value, utility is itself directly a value that liberalism champions. As my own prior work on utility has showed, Locke insists on an ontology of labor that valorizes utility as he simultaneously brandishes it as a metric to justify the colonial possession of lands from Native Americans.

18 But unlike tolerance, which is explicitly embraced as a moral value of liberalism, utility is not an explicitly moral value. Rather, it is framed as a crucial quality that plays a central role in distinguishing between those who do and those who do not merit the benefits of the social contract. Not explicitly and directly a moral value, utility functions as a foundational metric of social value in liberalism. This crucial role is what the transformations underway in cultures of neoliberalism are exposing and fraying.

By framing it as the constitutive objet a of the fantasy of neutrality, we can see how this social value of utility circulates strictly “off-screen.” Utility must not surface as having any direct or causal relation to neutrality as a core value of liberalism. Secured by its esoteric purity, neutrality commands assent as an aspirational, regulative ideal—or so it claims. But in reading utility as the cathexis that animates the fantasy of neutrality, we locate a sociopsychic register through which to query—and perhaps interrupt—this unreflective fealty to neutrality.

Siphoned off from any connection to neutrality, utility functions as an implicit, assumed value in liberalism, demanding its own direct fealty and cathexis. But the command seems to be lessening, as social authority more broadly is shifting and waning. While neutrality commands a kind of epistemological assent that, sanctified in the hallowed sphere of the law, simply seems beyond question, utility inhabits a much grittier, nastier social location. Caught up in racializing, sexualizing schemas, utility has never been pure or free from ideological warfare. As a groundless ground, the social cathexis with utility has always been political rather than moral, despite repeated attempts (often through Protestantism) to make it into a clear moral value commanding assent.

By framing it as the objet a that cathects us to neutrality, we can see more clearly how utility functions, namely, as a metric that, providing a clear and objective barometer to meritocracy, allows neutrality to circulate as a core value of liberalism. Utility does “the dirty work” of socioeconomic adjudication that neutrality eschews—indeed, that it disavows. Whether and how some bodies are judged as “different” while others are judged as “without difference” turn on this metric of utility. This deflection of the act of judging onto utility protects neutrality from any charge of bias: meritocracy, as determined by the scalar judgment of utility, is a purely economic calculation that does not infringe upon the sacred value of neutrality.

But its scalar distinctions have historically been taken up as binary judgments, demarcating clearly between those who are useful and those who are not. That is, the scalar economic distinctions of various degrees of utility have consistently been transformed into a binary judgment that subtends the moralism of meritocracy, while cloaking and grounding its systemic xenophobia (mostly as racist, but also as sexist, heterosexist, nationalist, ablest, ageist, and so on). This systemic xenophobia has rendered the social cathexis to utility always partial, embraced by those deemed useful and rightfully viewed with skepticism and suspicion by those alleged as unuseful. As the precarity of labor grows more intense, however, broadened beyond the racial and national schemas of liberalism through neoliberal practices, loyalty to the social metric of utility is fading across the social landscape. Reading it as the necessarily “off-screen” cause of the fantasy of neutrality, we see that the stakes of this social cathexis to utility are quite high—and also rather precarious.

The doubled fantasies of liberalism—tolerance and neutrality—thereby function differently. In the moral fantasy of tolerance, the

objet a of xenophobia cathects the fantasy precisely through its disavowal—it is the dirty little secret that cannot surface without puncturing the fantasy. In the epistemological fantasy of neutrality, the

objet a of utility cathects the fantasy by performing the labor of judgment that the fantasy necessarily disavows. While this disavowal is also required by the fantasy, the status of utility as an effective politico-economic barometer is vulnerable to sociopsychic refusal. Therefore, while the exposure of xenophobia may puncture the fantasy of tolerance, the force of liberalism as an ideology will likely quell any such challenge. (Remember, alignment with core, constitutive fantasies of the dominant culture determines the status of one’s own “realities”: the claim of xenophobia against liberalism can easily be dismissed as “deranged” or, more likely in the contemporary United States, as “playing the race card.”) To the contrary, the role of utility in the fantasy of neutrality relies on an ongoing social cathexis with it as a meaningful social metric. In neoliberalism, this role is fraying both materially and epistemologically and the core fantasy of neutrality is subsequently in danger.

INSTANT WEALTH AND FUNGIBLE DIFFERENCE

I return, finally, to the fantasy that has gained such social traction and cathexis in these neoliberal times: the fantasy of instant wealth. While the long historical view offered by Foucault cautions against proclaiming it a core, constitutive fantasy (it is too early to say), it is nevertheless enacting crucial sociopsychic transformations. Exemplifying the shift from desire to the drive, from the subject of rights to the subject of interests, the fantasy of instant wealth eschews any social cathexis to utility. Utility simply has no place in this fantasy. This precious objet a of liberalism’s core fantasy of neutrality thereby loses its mooring in this fantasy of instant wealth and the desiring subject itself begins to fade from the neoliberal episteme.

Trying to ferret out the transformation of liberal values underway in the neoliberal episteme, I want to push even further on what this specific fading entails and how it is happening. I contend that, as a shift from desire to the drive, it also displays a systemic move toward formalizing social difference itself. If this is so, then we begin to see how the waning of the social cathexis to utility reverberates in alterations in the social cathexis to xenophobia and its structuring of social difference, especially race; accordingly, the doubled core fantasies of neutrality and tolerance are also shifting ground and perhaps coming apart.

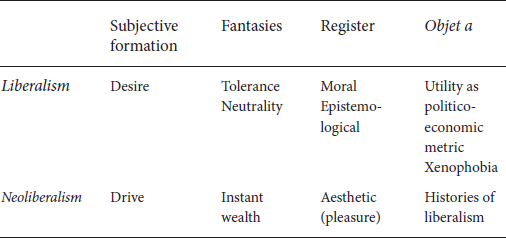

Before turning back to Foucault to analyze the shifts in norms and their metrics, I offer an expansion of the previous table to help track the changes I am excavating (see

table 3.2).

TABLE 3.2 The Structure of Liberalism’s and Neoliberalism’s Core Fantasies

To get at the reverberation from the waning of the social cathexis to utility in the social cathexis to xenophobia and its structuring of social difference, I return to Foucault and his broad work on the various historical iterations of norms. As I have showed in the previous two chapters, one of the critical transformations at work in the neoliberal episteme is the move away from contractual logic and its juridical rationality toward a logic of the market and its calculative rationality. Framing this as a process of intensification, I can now suggest that it can also be understood as shifts in cathexes from the contract to the market.

Recall that, as a site of veridiction, the market instantiates a calculative rationality as the most effective mode of thinking for the entrepreneurial subject of interests: as the circuit of the drive, the maximizing of interests becomes the site of cathexis, regardless of any social instantiation. In contrast, the juridical rationality of the contract primarily derives its social force from its authority: as a scene of desire, the subject, replete with deep internal reservoirs of moralizing emotions to be interpellated and structured into identifications by the symbolic, is the site of cathexis. This shift in the site of cathexis—from the subject to interests—sharpens our understanding of what is happening in the shift from a scene of desire to the circuit of the drive. In the erosion of symbolic investiture underway in neoliberalism, the social cathexes that animate the doubled core fantasies of liberalism begin to wane. But this is not merely a matter of newfound apathy toward authority: it is a shift in the social ontology away from the subject of desire and toward the circuit of the drive.

Given the long history of racialized and sexualized injustices—both explicit and disavowed (deflected onto the work of utility)—enacted through the juridical contract, the erosion of the symbolic and its interpellative force in the neoliberal episteme may appear to hold great promise of a better, less racist and sexist future. But such would only be the hopes of a symbolically interpellated subject cathected by such a desire, structured by lack, and forever anticipating a future that never quite arrives. From such a perspective, it might also appear that the social rationalities and practices of neoliberalism simply eschew all normalization, rooted as we are in conceptualizing norms vis-à-vis authority.

By developing the transformations in the dominant metrics of social value at work in the neoliberal episteme, I sharpen our understandings of exactly how the social cathexis to utility is waning—a process that is the effect not only of ideological disenchantment, but also of shifting material practices of labor and its social value. We will thereby gain a more precise schematic of how the cultural embrace of the neoliberal market’s calculative rationality registers in our concepts and enactments of social difference: when the liberal social metric of utility transforms into the neoliberal social metric of statistics, liberalism’s disavowed xenophobia also destabilizes.

As I have showed, when Foucault argues that, in the middle of the eighteenth century, the market displaces the role of the law as a juridical structure to limit the power of the state, this results in a fundamental split in the modes of rationality dominant in practices of liberalism, namely, the split between the juridical and calculative modes. As we begin to see the erosion of juridical authority in the neoliberal episteme, we also find the lapsing of modernity’s epistemology of certitude and a slide toward the neoliberal epistemology of calculating success—or the ascendancy of what I am calling ratio-calculative normativity, which is modulated through exactitude. As the neoliberal iteration of the modern episteme emerges alongside and “on top of” the older one of classical liberalism, juridical appeals to transcendental principles, such as those we find in contractual logic, are gradually displaced as possible modes of evaluative discernment: the calculation of interest, the barometer of acceptable profit and loss, becomes the acceptable mode of evaluation. These transformations in the very mechanisms of judgment both register in and are shaped by a transformation in the signifiers of social difference—and, eventually, in the ethical values—that they do or do not hold.

The exact contours of this shift from juridical to calculative normativity thus merit much investigation. In Sleights of the Norm, Mary Beth Mader has argued that the statistical conception of the norm is central to Foucault’s account of biopower. While most readings of Foucault have conceptualized biopower’s normalization as the gradual process of the homogenizing of cultural forms and values around particular nodes (medical, legal, familial, sexual, and so on), Mader intervenes with an incisive account of the epistemology of biopower’s norms as driven by the ascendancy of a numerical standardization of objects. Arguing explicitly against the understanding of Foucault’s norm as a custom or tradition, Mader dislodges the (disturbingly Althusserian-Butlerian) readings of it as a genealogy, history, or ancestry. To the contrary, Mader’s meticulous analysis shows how Foucault’s understanding of a norm turns on the immanently self-referential work of a statistical norm. This entails several crucial shifts, all of which express critical kinds of transformations underway in the neoliberal episteme: the elision of qualitative and quantitative judgment; the slide from binary to continuous, scalar modes of power; and the obfuscation of social exclusion or inclusion via the mathematical continuity inherent in the quantifying methods of gradation endemic to statistical analyses.

If we understand normalizing rationalities of the neoliberal episteme to function fundamentally through statistics, then Mader’s analysis explains how this entails a numerical standardization of objects. The norm as number—and especially as ratio—is necessarily abstracted from the object to which it purportedly refers. As Mader shows, for example, in a prolonged discussion of suicide rates, “The expression

suicide rate no longer refers to any person or persons but to a relation between numbers or quantities alone.”

19 She goes on to show how “the move from individual to rate, by way of the group, amounts to a radical shift of ontological register” (SR, 56). That the example here is suicide, not merely height or weight, only makes her work all the more poignant and disturbing: this abstraction of life may be endemic to the neoliberal episteme.

But as Mader pushes even further, suicide is not a kind of limit-case: it is exemplary. Because the reduction of the life-to-death transition to “the mathematical continuity of the number line, or an assumption of continuous quantity” (SR, 58), may still strike us as somehow perverse, this exemplarity is worth heeding. But make no mistake—this ontological elision from individual to group to number (and back again) is the crucially new social metric of the neoliberal episteme and its transformations of our social rationalities and practices. In our blind love of statistical norms, we enter “a

multidimensional space of comparison” (SR, 59), extending far beyond the binary, two-dimensional tables (say, of simple normal and abnormal or inclusion and exclusion) that we might continue to inhabit anachronistically.

20 The mean becomes the mediator of social relations: the epistemology of mathematical objects becomes the new social metric. Normalizing panopticism in neoliberalism is, to use Mader’s terms, “not architectural but statistical” (SR, 65).

Mader’s focus on statistical norms and their abstraction from referential objects, compounded by their immanent self-referentiality, articulates precisely the kind of transformation underway in neoliberal processes of subject formation and concepts of social difference. Abstracted from referentiality altogether, the numerical epistemology of the statistic exemplifies the kind of formalized ratio-calculative normativity that Foucault locates in neoliberal theorists.

21 We thereby begin to grasp the profound alteration in social metrics from liberalism’s fraught ideology of utility to neoliberalism’s exuberant embrace of numerically abstract statistics. No longer caught in the snares of an ideologically embattled and epistemologically fuzzy metric of utility, the neoliberal subject of interests thrives in the endless calculations of maximizing and enhancing afforded by this numerical metric of social comparability. It enables neoliberal subjects of interests to determine social values through the single barometer of economic calculation, extracted from any historico-social context. That is, the numerical metric of social comparability allows the flattening of the variegated phenomena of social difference to a singular characteristic and register: fungibility. And this is where the reverberations from this fraying of social cathexis to utility begin to surface in its twinned

objet a, xenophobia.

To be fungible is to have all character and content hollowed out. It is a relationship of equity that requires purely formal semblance. In economic terms, fungibility refers to those goods and products on the market that are substitutable for one another. For example, a bushel of wheat from Kazakhstan is fungible with a bushel of wheat from Kansas, assuming the quality and grade of wheat is the same. Fungibility undergirds the monetary system, since it is the formal quality of bank notes that allows them to be fully substitutable. This is different from exchangeable goods, which must be related to a common standard (such as money) in order to judge their differing or similar values. This central role of fungibility and not exchangeability in neoliberalism is thus one more reason to take our distance from Marxist analyses, with its focus on exchange, production, and consumption.

While this may all make sense at the level of economics, the problematic neoliberal twist is translating it from a dynamic of capital to a dynamic of “human capital”: this is arguably the site at which the neoliberal episteme appears to become ethically bankrupt. As the extensive work on the globalized disparities of wealth and poverty shows, the fungibility of human capital is rendering human labor precarious. Just as factory workers in the industrial revolution were expendable, so too has a great deal of contemporary labor become formally interchangeable: assembling technological gadgets can happen here or there (or, in the veiled nationalist language of the US market, “here or offshore”); but increasingly, so can more highly specialized activities, such as medical diagnoses, engineering solutions, and even market analyses.

As the work of Aihwa Ong in

Neoliberalism as Exception shows, the fungibility of human labor at all stratifications of socioeconomic class—from factories in Malaysia and Indonesia to “cyber heroes” of Silicon Valley—is quickly rendering all human labor both migrant and precarious. Even the human voice is fungible, as the training of telemarketers in Mumbai to mimic the “flat accent” of the Midwestern American renders their human capital fully fungible with any other “unaccented” voice in the United States. In the contemporary globalized labor market, saturated as it is by these neoliberal principles, the aim increasingly seems to be to secure a nonfungible skill: to do so, however, is no mean trick, since one must carefully balance the heightened specialization of such a nonfungible skill and its marketability. The market, after all, tells the truth—and it is increasingly transforming even the most highly specialized skills into fungible units. The exit from this intensifying of planned obsolescence is clear: enterprising innovation. (Just recall the immediate canonization of Steve Jobs.)

This move toward fungibility, away from exchangeability, as the market’s barometer transforms the category of social difference in significant and startling ways. Accordingly, it also transforms liberalism’s constitutive disavowal of xenophobia in significant and startling ways. When the market outstrips the contract in neoliberalism, its activity and production of social metrics must be constantly stimulated. Foucault emphasizes that, in the distancing from both Adam Smith and Marx (BB, 130), neoliberals do not claim that competition is a natural human state; rather, it is constantly stimulated by the activity of the market as the site of veridiction (BB, 118–21, 130). In order to achieve this constant stimulation of competition, the neoliberals (especially the ordoliberals in Germany) focus on “the formal properties of the competitive structure that assured, and could assure, economic regulation through the price mechanism” (BB, 131). As Ladelle McWhorter notes in her essay “Queer Economies,” Foucault specifies: “Competition is a principle of formalization.”

22Arguing explicitly against a welfare economy, the ordoliberals insisted that the fundamental objective of such policies to create and sustain the equalization of consumption across society was, actually, the death of economic growth. They argued that this crucial price mechanism, which generates the truths of the market, must “not [be] obtained through phenomena of equalization but through a game of differentiations” (BB, 142, my emphasis). Inequality is essential to stimulating market competition and, as such, is experienced by all members of the society. It is not that from which government ought to protect us. To the contrary, if the neoliberal aim of rendering the market the site of veridiction—across all aspects of society—is to be achieved, then inequality must be intensified and multiplied until the social fabric becomes a conglomeration of diffuse, fungible differences.

Social difference is thus not so much commodified, as bell hooks’s analysis from the 1990s argues;

23 nor is it simply to be erased in the name of globalized homogeneity, as early critics of neoliberalism have argued. Rather, difference must be intensified, multiplied, and fractured in the ongoing stimulation of competition: “The society regulated by reference to the market that the neoliberals are thinking about is a society in which the regulatory principle should not be so much the exchange of commodities as the mechanisms of competition” (BB, 147). We are far beyond the politics of multiculturalism: diversity is the explicit aim of neoliberalism, as so many have argued. But it is the explicit aim not as a tool of ideological obfuscation, but as a direct manifestation of the neoliberal social rationality in practice. Insofar as diversity follows out the logic of fungibility that the market demands, these celebrated differences are purely formal—they must be hollow, stripped of any historical residues, especially if those residues bring with them the ethical conflict of xenophobia. If we are to incite an antiracist praxis, such as those #BlackLivesMatter are attempting, we must ignite this agonistic history.

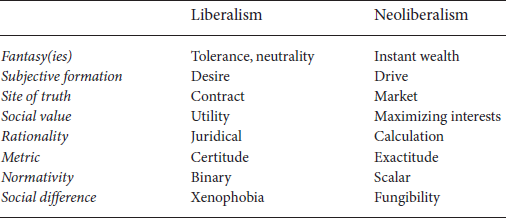

TABLE 3.3 Neoliberal Transformations of Liberalism

Following the schema of the table from

chapter 1, the Lacanian analyses I have offered here result in a considerable expansion (see

table 3.3). As I turn directly to the transformation of categories of social difference in the following two chapters, we will see how the affect of coolness captures so many of these cultural shifts underway in neoliberal social rationalities and practices. The transformation of coolness, with its roots deep in black culture, from an ethics of resistance and survival into a formally empty, aestheticized posture of the neoliberal episteme captures many of the ways we neoliberals understand and relate to social difference. Coolness perfectly expresses the neoliberal transformation of social difference from a historical repository of xenophobia to a fungible unit of rational calculation: coolness expresses difference-as-fungible.